Abstract

Background

Increasingly, public health interventions are delivered via telephone and/or text messages. Recent systematic reviews of early childhood obesity prevention interventions have not adequately reported on the way interventions are delivered and the experiences/perceptions of stakeholders. We aimed to summarise the literature in early childhood obesity prevention interventions delivered via telephone or text messages for evidence of application of process evaluation primarily to evaluate stakeholders’ acceptability of interventions.

Methods

A systematic search of major electronic databases was carried out using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes framework. Studies were included if interventions were delivered via telephone/text messages; aimed at changing caregivers’ behaviours to prevent early childhood obesity; with one or more outcomes related to early obesity risk factors such as breastfeeding, solid feeding, tummy time, sleep and settling, physical activity and screen time; published from inception to May 2020. All eligible studies were independently assessed by two reviewers using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias. Qualitative studies were assessed using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research and Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research tools.

Results

Twenty-four studies were eligible, and the overall risk of bias was low. Eight studies (33%) had evidence of process evaluation that examined participants’ perceptions of interventions. Participants appreciated the convenience of receiving interventions via telephone or text messages. 63% of all studies in this review showed improvement in one or more behaviours related to childhood obesity prevention. Participants were likely to modify behaviours if they received information from a credible source such as from health professionals.

Conclusion

There is limited reporting of stakeholders’ experiences in early obesity prevention studies delivered by telephone or text messages. Only one-third of studies examined participants’ acceptability and the potential for delivery of childhood obesity prevention interventions conveniently using this mode of delivery. Interventions delivered remotely via telephone or text messages have the potential to reach equal or a greater number of participants than those delivered via face-to-face methods. Future research should build in process evaluation alongside effectiveness measurements to provide important insight into intervention reach, acceptability and to inform scale up.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration: CRD42019108658

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The high prevalence of obesity is recognised world-wide, with an increasing interest in the prevention of obesity in the early years, from pre-birth up to and including 5 years of children’s age. Early childhood obesity prevention has gained momentum during the last decade, with a focus on children’s primary carergivers, mothers in most instances, as key agents to whom interventions are delivered [1,2,3,4]. Early prevention studies have utilised existing platforms such as mothers’/parents’ groups [3], child health clinics [4] and post-birth follow-up home visits by nurses [2] to deliver key messages to caregivers.

There has been an exponential growth of mobile phone ownership and its use globally, both in developed and developing countries alike [5, 6]. In Australia alone, an estimated 92% over the age of 18 used a mobile phone in 2012, additionally over half of those aged 25–34 were mobile-only phone users [7]. Public health and health promotion researchers have harnessed the increased dependability on mobile phones to deliver interventions via telephone and/or text messages [8, 9]. Crucially, this mode of delivery was welcomed for its cost-effectiveness [10], ability to reach wider population [11] and its acceptability to those receiving the interventions [12].

Population-wide increases in communication via telephone and/or text messages has led to growth in the number of interventions delivered using these modes in clinical care, public health and health promotion. Earlier examples have included text messages to patients to send medical appointment reminders [13], text messages for routine chronic disease management [14, 15], and telephone calls for mental health management [16]. There has also been extensive use of telephone calls and/or text messages by public health and health promotion researchers to communicate health promotion messages and public health interventions [17, 18]. Similarly, there has been a growth in the number of studies using mobile phones to communicate key messages to new caregivers and women with young children [1, 19, 20].

To date, findings of systematic reviews of telephone and text message support have suggested improved outcomes among several groups: in pregnant women and new mothers who received telephone support for smoking, breastfeeding, birthweight and postpartum depression [21]; in adults who received telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary outcomes [22]; in pregnant women who received telephone support for depression and breastfeeding during pregnancy and post-birth [23]; and in adolescents who received text message interventions for physical activity and sedentary behaviours [24]. Interventions for childhood obesity prevention or behaviour change delivered via telephone or text messages and their effectiveness have been established and reported, however process evaluation among study participants as well as stakeholders is often less well reported [25, 26].

In this systematic review, we aimed to examine early childhood obesity prevention interventions delivered via telephone or text messages (solely or supplementary to traditional modes), for evidence of process evaluation. Our objective was to explore the acceptability of the interventions to stakeholders, primarily to participants, intervention deliverers, health managers and policymakers.

Methods

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) standardised reporting guidelines and checklist [27].

Protocol and registration

A protocol was developed prior to the review process and was registered with the International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). It can be accessed via (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ registration number: CRD42019108658).

Eligibility, study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible studies were identified using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICO) framework [28]. Patient Problem (or Population) – pregnant women or caregivers who received childhood obesity prevention interventions for children from birth up to and including 5 years of age. Intervention – interventions aimed at changing caregivers’ behaviours to prevent early childhood obesity; delivered via telephone (including via telephone applications (apps)) or text messages primarily or supplementary to face-to-face or online methods. Comparison or control – caregivers who received usual care or maintenance care (for example, control group in randomised controlled trials (RCT), non-equivalent control group in quasi-experimental design). Outcome – one or more early obesity prevention or behaviour change outcomes such as body mass index (BMI), breastfeeding, solid feeding, “tummy time” (allowing babies time lying prone on their abdomen while they are awake), sleep and settling, physical activity, screen time and participant well-being.

The review encompassed intervention studies including randomised and cluster-randomised controlled trials, case control studies, quasi-experimental studies without comparators and descriptive studies with evidence of program outcome(s). The review included studies that delivered interventions via telephone (including apps) or text messages (solely or supplementary to traditional modes). We focussed specifically on those studies undertaking process evaluation to explore participant and health professional experiences. Studies were excluded if they did not have at least one childhood obesity related or behaviour change outcome, and if studies only reported outcomes of children older than 5 years of age.

Information sources

The following databases were searched from their inception to 15 May 2020, to identify eligible trials: MEDLINE (OVID; 1966), Scopus (Elsevier 1980), Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics post-2016, Thomson Reuters pre-2016); CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost; 1994), the Cochrane Library databases, Database of Systematic Reviews, and the US National Library of Medicine’s ClinicalTrials.gov. We also searched the reference lists of several relevant systematic and narrative reviews, grey literature including doctoral theses and conference proceedings, relevant government websites, Google Scholar and Google Search.

Search

Preliminary literature searches were carried out in 2018 to assess the feasibility of the review. The full electronic search strategy is provided in Table 1. A comprehensive literature search was conducted by one author (ME) in May 2019 and repeated in May 2020.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts of references were independently screened by two reviewers (ME and SE) in Covidence systematic review software (www.covidence.org). Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (SM), where necessary. Following the retrieval of full texts, the same two reviewers independently screened them against the specified inclusion/exclusion criteria defined above. Papers relating to the same trial were grouped into one study.

Data collection process

Records from all databases and hand searches were imported or recorded into a reference management software package (Endnote version X9) and then exported from Endnote to Covidence. Duplicate records were removed. Any additional articles identified from reference lists of included trials were included to supplement the analysis.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a data extraction table that represented the categories of intended data items which were tested and piloted for feedback from all authors. After agreement was reached, ME extracted all data that were reviewed by at least one other author (Table 2). For those studies without reported outcomes, we contacted authors of the trials to obtain the required data.

Process evaluation

We analysed all eligible studies (and associated published literature) that described process evaluation or assessed program satisfaction through quantitative and/or qualitative surveys. Although process evaluation includes several components, we focussed on stakeholders’ perceptions of interventions that are fundamental to their subsequent implementation and effectiveness. Some process evaluation measures that we explored included continued participation (retention), ease and convenience of delivering interventions (feasibility), acceptability of interventions by participants, adherence to advice provided, and experiences of participants, intervention deliverers and researchers.

Planned methods of analysis

Comprehensive analysis of all eligible studies (and related published literature) was undertaken to identify studies that conducted process evaluation. We gathered and analysed data informed by the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) [49]. The data included name, theoretical framework, what interventions were delivered, who delivered the interventions, how (mode of delivery), where the interventions were delivered (intervention setting), number of times and over what period the interventions were delivered or dose (number of sessions and frequency of intervention delivery), and intervention adherence or fidelity (retention). Additionally, we gathered data relevant to this review such as design, objectives, outcomes, parity or birth order. For synthesis of process evaluation data, a convergent segregated approach [50, 51] was used to firstly enable synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence within studies, followed by narrative synthesis to determine the experiences / perceptions of participants and health professionals (where available) who received or delivered the interventions [50, 52]. For ongoing studies, we tried to contact the study investigator where possible to obtain further information.

Risk of bias in individual studies

All eligible studies were independently assessed by two reviewers (ME and SE) using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias [53]. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer, when necessary. Studies that met the eligibility criteria were assessed for all five domains, namely, randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcome, and selection of the reported result [53]. Risk was reported as ‘high’ or ‘low’ or ‘some concerns’, as recommended in the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2) revised tool [54].

Assessment of qualitative studies

While risk of bias assessment enables confidence that estimates of effect are near true values for outcomes, it does not assess the qualitative inquiry [53]. Therefore, eligible qualitative studies that demonstrated evidence of process evaluation, satisfaction or feasibility measures were assessed for rigour to investigate the extent to which study authors conduced their research to the highest possible standards. Studies were assessed against the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [55] and the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklists [56]. COREQ and SRQR include 32-item and 21-item checklists, respectively, that draw together important aspects of qualitative research to assess the reporting of relevant information. There are three broad domains in COREQ: research team and reflexivity (personal characteristics, relationship with participants); study design (theoretical framework, participant selection, setting, data collection); and analysis and findings (data analysis, reporting). In SRQR, the first two items are the article’s title and abstract; the remaining 19 items relate to congruity between authors’: problem formulation and research question; research design and methods of data collection and analysis; results, interpretation, discussion, and integration; and other information.

Results

Study selection

We identified 1028 records after the systematic conduct of electronic and hand searches. After duplicate removal, title and abstract screening, 106 references were selected for full-text review. Twenty-four studies were finally included in this review (Fig. 1). A list of included studies is provided in Table 2.

Characteristics of studies

Key study characteristics are presented below and described in detail in Table 3.

Study design and participation rates

The majority of identified studies (19 out of 24) were published in the last decade, of which one-half were published within the last 4 years. Sixty-three percent of studies were conducted in the USA or Australia. The majority (80%) were RCTs, of which 18 were individual RCTs and two were cluster RCTs; two had a quasi-experimental design and the remaining two studies were pragmatic. Key study characteristics are represented in Table 3. Retention rates ranged from 71 to 100%, and 16 studies (67%) indicated participant retention rates of greater than 80%.

Setting and medium of intervention delivery

More than half (54%) of the studies (13 of 24) delivered interventions exclusively and flexibly via telephone and/or text messages where participants or deliverers did not need to go to a predetermined location to receive or deliver interventions. The remainder were face-to-face sessions, group sessions or home visits supplemented by telephone or text messages.

Target population

Interventions were delivered to caregivers who were predominantly women. Intervention delivery commenced as early as when women were pregnant (25%), as well as when the children were < 3 months of age (42%), 4–12 months of age (16%) and > 12 months of age (17%). In studies where the mean age of participants was reported (n = 20), the majority (60%) were aged 30 years or under. Parity was reported by 14 studies (58%); five of these studies delivered interventions to first-time mothers only.

Intervention characteristics

Almost one-half of the studies (46%) delivered interventions for a period of 6 months or less, 29% delivered interventions for a period of 7–12 months, 17% delivered interventions for a period of 13–24 months, while 8% delivered interventions for longer than 24 months. Interventions were delivered via nurses or midwives (38%), health educators (17%), dietitians (8%), or automated text messages, apps or online (21%).

Intervention components

Interventions were delivered for breastfeeding, food and drink intake, “tummy time” (allowing babies time lying prone on their abdomen while they are awake), play time / physical activity, sleep, screen time, goal-setting and maternal well-being. The number of outcomes measured typically varied between one and four, with most studies reporting fewer than four outcomes.

Risk of bias within studies

We included all types of studies in this review, hence in the domain ‘randomisation process’ four studies were judged as having ‘some concerns’ as they did not randomise participants or lacked adequate information on the randomisation process. For the domain ‘deviation from intended outcomes’, seven studies were judged as having ‘some concerns’ as they did not provide adequate information on the blinding of participants and intervention deliverers. Nineteen studies had high participant retention rates (> 70%) and were judged as low risk; five had low participant retention which were assessed as high risk in the ‘missing outcomes data’ domain. Information on ‘measurement of outcome’ was provided clearly by 16 studies, the remaining 8 studies that lacked adequate information or were ongoing were judged as having ‘some concerns’. Eleven studies in this review stated that more than one outcome and/or outcomes were measured at various time points; therefore, in the domain ‘reporting of the selected results’, studies without published evidence of outcomes at the various time points were judged as having ‘some concerns’. Risk of bias is represented in Fig. 2. Full details of our assessment of bias are in Table 4. Five studies had low risk of bias in all five domains.

Outcomes / effectiveness of studies

There were 24 eligible studies in this review, with details of outcomes of studies provided in Table 5. Sixteen studies measured anthropometric outcomes of which less than a quarter reported statistically significant age appropriate lower BMI z-score (BMIz) in the intervention group in comparison to the control group. Thirteen studies measured age appropriate BMIz [1,2,3, 19, 29, 30, 33,34,35, 40, 42, 43, 47] and three measured age appropriate weight gain in children as an outcome [36, 41, 48] . Sixteen studies measured duration of breastfeeding [1, 2, 19, 29, 31,32,33, 37,38,39,40, 42, 44,45,46, 48]; 15 studies reported on solids feeding or food habits of the children [1,2,3, 19, 30, 33, 34, 38,39,40,41,42,43, 47, 48]; 3 studies reported on the practice of tummy time [1, 2, 19]; 5 studies reported on play time / physical activity in children [1, 2, 19, 34, 58]; 4 studies reported on sleep duration / sleep quality [1, 2, 19, 35]; and 7 studies reported on children’s screen time/ television (TV) viewing time [1,2,3, 19, 34, 35, 48] (Table 5).

Over two-fifths (44%; 7 of 16) demonstrated an increase in breastfeeding duration, 47% (7 of 15) reported improved food habits in children. Changes in feeding habits included: reduction in non-core drink consumption at 9 months of children’s age [57], and reduction in juice consumption and sugary drinks at 4 years of children’s age [43, 58, 59] in the intervention group in comparison to the control. There were higher odds of appropriate timing of introduction of solids in the intervention group in comparison to the control group (at 6–7 months of children’s age) [60,61,62]. 67% (2 of 3) reported increased practice of “tummy time”, 20% (1 of 5) reported an increase in children’s duration of outdoor activities, 50% (2 of 4) reported an increase in sleep duration of children, and 43% (3 of 7) reported a decrease in TV viewing or screen time.

We also looked for commonalities between effectiveness of interventions and mode of delivery. Of the studies that showed improvements in behaviours related to childhood obesity, 53% (8 of 15) were delivered solely via telephone or text messages.

Process evaluation

Eight studies (33%) had evidence of process evaluation or satisfaction measures [1, 3, 32, 33, 38, 40,41,42]. All eight studies quantitatively measured participant satisfaction at the time interventions were delivered. Qualitative interviews with trial participants were conducted by three studies during the intervention phase [63,64,65] and by five studies post-intervention [32, 33, 66,67,68], with only one study measuring perceptions of participants and recruiters during the recruitment phase [69]. Details of this analysis are shown in supplementary file 1. Our assessment of the qualitative studies against the COREQ criteria showed that all studies except one (that included a self-assessment against COREQ) had insufficient information (supplementary file 2). Hence, we assessed the studies against the SRQR criteria: six studies reported sufficient information (supplementary file 3).

Four of the eight studies were conducted in Australia, two were collaborative studies with Australia conducted in China and Myanmar, one study was in the UK and one in Hawai’i/Puerto Rico. Six studies measured BMIz or weight change of which one study noted a decrease in weight gain in comparison to the control. Three studies noted increased breastfeeding rates and three studies observed improved feeding habits in comparison to the control. Two studies that targeted screen time in children found a reduction in screen time in comparison to the control. One study that targeted a range of behaviours observed an earlier start of tummy time by participants in comparison to the control (Table 5).

Participants’ perceptions / satisfaction with the program during the intervention phase of the study were evaluated by three studies through in-depth interviews [65], qualitative interviews [64] and semi-structured qualitative interviews with a purposive sample of participants during intervention phase [63]. Five studies evaluated participants’ perceptions upon completion of the intervention or post-intervention period through semi-structured interviews [68], semi-structured telephone interviews with purposive sampling [67], qualitative interviews [66], a questionnaire with open-ended process evaluation questions [32] and an in-person exit interview [33]. Additional process evaluation components included examination of researchers’ diaries, field records, project meeting minutes [64], and interviews with participants and recruiters during the recruitment phase to assess facilitators and challenges in recruiting pregnant women to trials [69] (Table 6).

Process evaluation of the recruitment phase of the studies indicated that participants consented to participate due to the convenience of the delivery mode via telephone or text messages [69]. Evaluation of participants’ experience indicated that participants were likely to modify behaviour if they received information from a credible source such as from health professionals [63,64,65, 67]. Delivery of interventions via text messages facilitated sharing of messages with family and friends [63, 64]. Participants were more likely to adhere to recommendations and change behaviours if the content delivered aligned with their pre-existing beliefs [33, 67]. Participants’ levels of engagement with programs fluctuated based on their needs and their available time at later stages of their children’s development [33, 63, 67]. Participation via telephone and by text messages was convenient to participants [63], and participants expressed preferences for receiving interventions through a combination of non-face-to-face delivery modes including but not limited to text messages, telephone, emails, Web and push notifications [63, 67]. The programs were more appealing to first-time caregivers in comparison to those who cared for previous children [63, 66, 67] and participants considered themselves well supported through participation [32, 63]. Some barriers to participation included: lack of personalisation of text messages [63, 64]; participants’ lack of time due to return to work [63, 66]; and where participants perceived that high expectations were placed on them as mothers [63]. The process evaluation findings are represented in Table 6.

Discussion

Key findings

The objective of this systematic review was to explore the acceptability of the interventions to stakeholders through process evaluation of early childhood obesity prevention studies. Of the 24 eligible studies that delivered interventions via telephone or text messages, only one-third of studies (n = 8) examined stakeholder perceptions, with all of these studies focussing on the satisfaction / acceptability of the interventions that were delivered to participants. We found no evidence of evaluation of perceptions of other key stakeholders including those who delivered the interventions or health managers or policymakers, and no evidence of other process evaluation measures such as reach or fidelity.

Process evaluation findings highlight participants’ appreciation of the convenience of receiving interventions via telephone or text messages [63, 69], and the importance of delivering interventions from credible sources for participants’ compliance with interventions and behaviour changes [63,64,65, 67]. Level of engagement in a program was not dependent on the mode of delivery but was dictated by participants’ needs and on their children’s developmental stage [33, 63, 67]. Although participants perceived telephone or text messages as convenient, they expressed preference to be able to receive interventions through a combination of one or more delivery methods, namely, telephone, text messages, Web, apps with optional face-to-face [63, 66, 67]. Participants highlighted the co-benefits they received, such as early identification of any issues (clinical, social or similar needs) and referral to appropriate services. Participants considered themselves well supported [32, 63], with first-time caregivers considering the programs more valuable than those who had previous children [63, 66, 67]. Participants expressed some barriers to participation such as lack of personalisation of content in text messages [63, 64], lack of time due to return to work (irrespective of the mode of delivery) [63, 66] and a perception that high expectations were placed on them as mothers [63].

The growth in childhood obesity prevention interventions delivered by telephone/text messages is shown by the large proportion of studies conducted in the last decade. Similar to previous systematic reviews of childhood obesity prevention interventions [25, 70], several outcomes were measured including BMIz or weight gain, breastfeeding, solid feeding/food habits, tummy time, play time/physical activity, sleep duration/sleep quality, screen time/TV viewing, goal-setting and mother’s well-being. Less than one-quarter (23%; 3 of 13) of the studies that measured outcomes for weight and BMIz reported a statistically significant decrease in weight gain or a lower BMIz score in comparison to the control [25, 70, 71], while over three-fifths (63%; 15 of 24) of all studies in this review showed improvement in one or more behaviours related to childhood obesity prevention. Previous reviews have reported inconsistent outcomes for behaviour changes [25, 70]. Studies that were included in this review provided interventions for “tummy time” and sleep duration that were not included in previous reviews. These outcomes suggest that while it is more difficult to change weight outcomes such as BMIz, interventions delivered by telephone can be effective in supporting behaviours important for the prevention of obesity.

Delivery of interventions remotely via telephone has been proven to be more cost-effective [72]. Although text only studies would be the most cost-effective method of delivery, there was limited evidence in this review, with just three studies delivering interventions solely via text messages for breastfeeding of which two demonstrated an increase in exclusive breastfeeding. The average retention rates for studies delivered with and without a face-to-face component were both 85%. This may suggest that interventions delivered remotely via telephone or text messages have the potential to reach, attract and retain equal or a greater number of participants than those delivered via face-to-face modes. This implies that childhood obesity prevention interventions delivered via telephone or text messages have the potential to be more cost-effective and have equal or greater reach than interventions that include a face-to-face component.

Comparison with prior reviews

Previous systematic reviews of early childhood obesity (0–5 years of age) prevention trials have not examined process evaluation or participant involvement but have recommended inclusion of these components for improved quality and relevance [25]. Although the focus of previous reviews was not on delivery of interventions via telephone or text messages, multiple modes of traditional delivery methods were employed [73] and the reviews recommended exploring intervention delivery via low cost methods such as telephone and the internet [71]. Three of the previous reviews examined delivery of interventions exclusively by healthcare professionals e.g., research nurses, lactation consultants, psychologists and social workers [25, 70, 74]. Similarly, in almost four-fifths of the studies in this review, interventions were delivered by health professionals such as nurses, midwives, health educators, or dietitians; and in one-fifth, interventions were delivered via automated text messages, apps or online.

Systematic reviews of obesity prevention interventions delivered to older children and adolescents (12–24 years of age) using mobile technologies have noted heterogeneity in research design and in the interventions delivered [75,76,77]. These reviews observed a small number of studies that delivered interventions to adolescents and young adults via telephone, text messages or mobile apps. Very limited or post hoc process evaluation studies were noted [76] and research in this area was considered to be in its infancy with further research required to elucidate effectiveness [75, 76].

Previous reviews have not reported on process evaluation literature but noted its potential value [26, 71, 76]. Process evaluation findings in this review demonstrate that participants valued and trusted interventions delivered from credible sources, hence intervention deliverers are crucial to the acceptability of interventions. Thorough reporting of recruitment and training of intervention deliverers is important in replicating intervention effects during scale up [26, 71]. This review demonstrates limited evidence of evaluation of participants’ perceptions and a lack of evidence that existing studies have examined the perceptions of intervention deliverers, health professionals and policymakers.

Public health implications

Evidence gathered through process evaluation of trials contribute crucial knowledge to refinement of interventions and programs prior to their replication and scale up [78, 79]. Additionally, process evaluation of trials facilitates integration of qualitative and quantitative methods that yields rich detail about study outcomes that neither method could achieve alone [78, 80]. Although process evaluation has been in existence for over two decades, only one-third of the studies in this review had evidence of process evaluation or satisfaction measurement, demonstrating the limited number of studies that conducted process evaluation to measure stakeholder perception. The findings from this review provide important insights for researchers about the importance of conducting process evaluation alongside trials to explore the perceptions of stakeholders in addition to evaluating effectiveness of interventions. While outcome measures of childhood obesity prevention interventions are indicative of the success of programs delivered to caregivers with young children, a key component of the success is attributed to the acceptability of, and compliance with the program by its participants.

Although process evaluation often takes a back seat to impact evaluation, information about stakeholders’ perceptions and how a program is implemented, makes it easier to understand why participants did or did not gain some benefit from participating in the program [81]. Stakeholder feedback obtained as a result of process evaluation is important for modifying and improving interventions to enhance engagement, retention and effectiveness of programs prior to scale up [78, 81]. In circumstances where comprehensive process evaluation is not feasible due to limited resources or time pressures in trial environments, at a minimum, evaluating the perceptions of participants, intervention deliverers, health managers and policymakers during or immediately after intervention delivery is warranted [78].

Review strengths and limitations

This systematic review has a number of strengths. The scope and search for this systematic review was comprehensive and conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) standardised reporting guidelines and checklist [27]. A protocol was developed prior to the review process and registered with PROSPERO. Eligible studies were identified using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICO) framework [28]. Titles and abstracts of references were independently screened by two reviewers in Covidence. Data were gathered and analysed similar to that described in the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) [49]. Risk of bias for all eligible studies was independently assessed by two reviewers using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias [53]. Qualitative studies were assessed using the COREQ and SRQR tools [55, 56], our assessment demonstrated lack of evidence of elements described in the tools. One recommendation is for qualitative studies to include self-assessment against a standard tool.

However, this review only included peer-reviewed papers published in English. Therefore, we may have missed peer-reviewed literature published in other languages. Despite our best efforts to obtain further information from study investigators of ongoing trials, this review was not able to include information on those ongoing or unpublished studies, and two studies did not conduct process evaluation as planned. The main limitation of this review stems from the small number of studies that conducted and reported process evaluation data, limiting our ability to describe effective engagement and retention approaches for scale up of programs.

Conclusion

Of the 24 studies included in this review, only one-third reported process evaluation to measure perceptions of participants. Evaluation of participants’ experiences during recruitment and intervention phases demonstrated the potential for childhood obesity prevention interventions to be delivered conveniently via telephone or inexpensively via text messages. Interventions delivered remotely via telephone or text messages have the potential to reach, attract and retain equal or a greater number of participants than those delivered via face-to-face methods. While outcomes for weight varied, many of the studies in this review showed improvements in behaviours related to childhood obesity. This review shows that the conduct of process evaluation alongside trials is uncommon, future studies should build in process evaluation alongside effectiveness measurements to provide important insight into intervention reach, acceptability and to inform scale up.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BMIz:

-

Age and sex standardized body mass index z-score

- PICO:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes

- SRQR:

-

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- PROSPERO:

-

Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews

- TIDieR:

-

Template for intervention description and replication

References

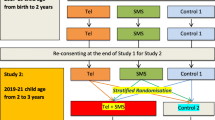

Wen LM, Rissel C, Baur LA, Hayes AJ, Xu H, Whelan A, et al. A 3-arm randomised controlled trial of communicating healthy beginnings advice by telephone (CHAT) to mothers with infants to prevent childhood obesity. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):79 PubMed PMID: 28088203.

Wen LM, Baur LA, Rissel C, Wardle K, Alperstein G, Simpson JM. Early intervention of multiple home visits to prevent childhood obesity in a disadvantaged population: a home-based randomised controlled trial (Healthy Beginnings Trial). BMC Public Health. 2007;7 PubMed PMID: WOS:000247035500001.

Campbell K, Hesketh K, Crawford D, Salmon J, Ball K, McCallum Z. The Infant Feeding Activity and Nutrition Trial (INFANT) an early intervention to prevent childhood obesity: Cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):103.

Daniels LA, Magarey A, Battistutta D, Nicholson JM, Farrell A, Davidson G, et al. The NOURISH randomised control trial: Positive feeding practices and food preferences in early childhood - A primary prevention program for childhood obesity. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):387.

Hussain T, Smith P, Yee LM. Mobile phone–based behavioral interventions in pregnancy to promote maternal and fetal health in high-income countries: systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020;8(5):e15111.

Vasudevan L, Ostermann J, Moses SM, Ngadaya E, Mfinanga SG. Patterns of mobile phone ownership and use among pregnant women in southern Tanzania: cross-sectional survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020;8(4):e17122.

ACMA. Communications report 2011–12 series report 3—smartphones and tablets take-up and use in Australia. Summary report. In: Authority ACM, editor. Australia: ACMA; 2012.

Demirci JR, Suffoletto B, Doman J, Glasser M, Chang JC, Sereika SM, et al. The development and evaluation of a text message program to prevent perceived insufficient milk among first-time mothers: retrospective analysis of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020;8(4):e17328.

Munro S, Hui A, Salmons V, Solomon C, Gemmell E, Torabi N, et al. SmartMom text messaging for prenatal education: a qualitative focus group study to explore Canadian women’s perceptions. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(1):e7.

Gold J, Lim MS, Hellard ME, Hocking JS, Keogh L. What’s in a message? Delivering sexual health promotion to young people in Australia via text messaging. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):792.

Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–73.

Job JR, Spark LC, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG, Reeves MM. Women’s perceptions of participation in an extended contact text message–based weight loss intervention: an explorative study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017;5(2):e21.

Guy R, Hocking J, Wand H, Stott S, Ali H, Kaldor J. How effective are short message service reminders at increasing clinic attendance? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(2):614–32 PubMed PMID: WOS:000301229300005. English.

Chow CK, Redfern J, Hillis GS, Thakkar J, Santo K, Hackett ML, et al. Effect of lifestyle-focused text messaging on risk factor modification in patients with coronary heart disease. Jama. 2015;314(12):1255.

Buis LR, Hirzel L, Turske SA, Des Jardins TR, Yarandi H, Bondurant P. Use of a text message program to raise type 2 diabetes risk awareness and promote health behavior change (part I): assessment of participant reach and adoption. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(12):e281.

Leach LS, Christensen H. A systematic review of telephone-based interventions for mental disorders. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(3):122–9.

Sharifi M, Dryden EM, Horan CM, Price S, Marshall R, Hacker K, et al. Leveraging text messaging and mobile technology to support pediatric obesity-related behavior change: a qualitative study using parent focus groups and interviews. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(12).

Jenkins A, Christensen H, Walker JG, Dear K. The effectiveness of distance interventions for increasing physical activity: a review. Am J Health Promot. 2009;24(2):102–17 PubMed PMID: WOS:000271993100004. English.

Wen LM, Rissel C, Xu H, Taki S, Smith W, Bedford K, et al. Linking two randomised controlled trials for healthy beginnings©: optimising early obesity prevention programs for children under 3 years. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):739 PubMed PMID: 31196026.

Denney-Wilson E, Laws R, Russell CG, Ong KL, Taki S, Elliot R, et al. Preventing obesity in infants: the growing healthy feasibility trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009258.

Dennis C-L, Kingston D. A systematic review of telephone support for women during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. JOGNN J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(3):301–14.

Goode AD, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):81–8.

Lavender T, Richens Y, Milan SJ, Smyth RMD, Dowswell T. Telephone support for women during pregnancy and the first six weeks postpartum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev U6 - U7 J Artic. 2013;(7):CD009338.

Ludwig K, Arthur R, Sculthorpe N, Fountain H, Buchan DS. Text messaging interventions for improvement in physical activity and sedentary behavior in youth: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(9):e10799 Epub 17.09.2018. English.

Hennessy M, Heary C, Laws R, van Rhoon L, Toomey E, Wolstenholme H, et al. The effectiveness of health professional-delivered interventions during the first 1000 days to prevent overweight/obesity in children: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019:1–17.

Toomey E, Matvienko-Sikar K, Heary C, Delaney L, Queally M, Hayes CB, et al. Intervention fidelity within trials of infant feeding behavioral interventions to prevent childhood obesity: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(1):75–97.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16.

Carlsen EM, Kyhnaeb A, Renault KM, Cortes D, Michaelsen KF, Pryds O. Telephone-based support prolongs breastfeeding duration in obese women: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(5):1226–32 PubMed PMID: 24004897.

Döring N, Hansson LM, Andersson ES, Bohman B, Westin M, Magnusson M, et al. Primary prevention of childhood obesity through counselling sessions at Swedish child health centres: design, methods and baseline sample characteristics of the PRIMROSE cluster-randomised trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):335.

Franco-Antonio C, Calderón-García JF, Vilar-López R, Portillo-Santamaría M, Navas-Pérez JF, Cordovilla-Guardia S. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a brief motivational intervention to improve exclusive breastfeeding rates: study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(4):888–97.

Gallegos D, Russell-Bennett R, Previte J, Parkinson J. Can a text message a week improve breastfeeding? Bmc Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14 PubMed PMID: WOS:000346748100001.

Gibby CLK, Palacios C, Campos M, Graulau RE, Banna J. Acceptability of a text message-based intervention for obesity prevention in infants from Hawai'i and Puerto Rico WIC. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):291 PubMed PMID: 31409286. eng.

Gorin AA, Wiley J, Ohannessian CM, Hernandez D, Grant A, Cloutier MM. Steps to Growing Up Healthy: a pediatric primary care based obesity prevention program for young children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14 PubMed PMID: WOS:000332709600001.

Haines J, McDonald J, O'Brien A, Sherry B, Bottino CJ, Schmidt ME, et al. Healthy habits, happy homes: randomized trial to improve household routines for obesity prevention among preschool-aged children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1072–9 PubMed PMID: 24019074.

Hannan J. APN telephone follow up to low-income first time mothers. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(1–2):262–70.

Harris-Luna ML, Badr LK. Pragmatic trial to evaluate the effect of a promotora telephone intervention on the duration of breastfeeding. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2018;47(6):738–48.

Hmone MP, Li M, Alam A, Dibley MJ. Mobile phone short messages to improve exclusive breastfeeding and reduce adverse infant feeding practices: protocol for a randomized controlled trial in Yangon, Myanmar. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(6):e126-e PubMed PMID: 28659252. eng.

Horodynski MA, Olson B, Baker S, Brophy-Herb H, Auld G, Van Egeren L, et al. Healthy babies through infant-centered feeding protocol: an intervention targeting early childhood obesity in vulnerable populations. BMC Public Health. 2011;11 PubMed PMID: WOS:000297504600001.

Jiang H, Li M, Wen LM, Hu QZ, Yang DL, He GS, et al. Effect of short message service on infant feeding practice findings from a community-based study in Shanghai, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(5):471–8 PubMed PMID: WOS:000336840200014.

Lakshman R, Whittle F, Hardeman W, Suhrcke M, Wilson E, Griffin S, et al. Effectiveness of a behavioural intervention to prevent excessive weight gain during infancy (The Baby Milk Trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16 PubMed PMID: WOS:000362249700001.

Laws RA, Denney-Wilson EA, Taki S, Russell CG, Zheng M, Litterbach EK, et al. Key lessons and impact of the growing healthy mHealth program on milk feeding, timing of introduction of solids, and infant growth: quasi-experimental study. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2018;6(4):e78 PubMed PMID: 29674313.

Nezami BT, Ward DS, Lytle LA, Ennett ST, Tate DF. A mHealth randomized controlled trial to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake in preschool-aged children. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13(11):668–76 PubMed PMID: WOS:000449476600007.

Patel A, Kuhite P, Puranik A, Khan SS, Borkar J, Dhande L. Effectiveness of weekly cell phone counselling calls and daily text messages to improve breastfeeding indicators. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):337 PubMed PMID: 30376823.

Pugh LC, Serwint JR, Frick KD, Nanda JP, Sharps PW, Spatz DL, et al. A randomized controlled community-based trial to improve breastfeeding rates among urban low-income mothers. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(1):14–20.

Tahir NM, Al-Sadat N. Does telephone lactation counselling improve breastfeeding practices?: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):16–25.

van der Veek SMC, de Graaf C, de Vries JHM, Jager G, Vereijken CMJL, Weenen H, et al. Baby’s first bites: a randomized controlled trial to assess the effects of vegetable-exposure and sensitive feeding on vegetable acceptance, eating behavior and weight gain in infants and toddlers. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):266.

Wasser HM, Thompson AL, Suchindran CM, Hodges EA, Goldman BD, Perrin EM, et al. Family-based obesity prevention for infants: Design of the “Mothers & Others” randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;60:24–33 PubMed PMID: WOS:000407981100003.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ Br Med J. 2014;348:g1687.

Lizarondo L, Stern C, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, et al. Chapter 8: mixed methods systematic reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Res Sch. 2006;13(1):29 PubMed PMID: 20098638. eng.

Zhang Y, Alonso-Coello P, Guyatt GH, Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Akl EA, Hazlewood G, et al. GRADE Guidelines: 19. Assessing the certainty of evidence in the importance of outcomes or values and preferences—Risk of bias and indirectness. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:94–104.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2011;343(oct18 2):d5928-d.

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2019;366.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51 PubMed PMID: 00001888–201409000-00021.

Campbell KJ, Lioret S, McNaughton SA, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Ball K, et al. A parent-focused intervention to reduce infant obesity risk behaviors: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):652.

Döring N, Ghaderi A, Bohman B, Heitmann BL, Larsson C, Berglind D, et al. Motivational interviewing to prevent childhood obesity: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20153104.

Cloutier MM, Wiley J, Huedo-Medina T, Ohannessian CM, Grant A, Hernandez D, et al. Outcomes from a pediatric primary care weight management program: steps to growing up healthy. J Pediatr. 2015;167(2):372–7.e1 PubMed PMID: 26073106.

Xu H, Wen LM, Rissel C, Flood VM, Baur LA. Parenting style and dietary behaviour of young children. Findings from the healthy beginnings trial. Appetite. 2013;71:171–7.

Wen LM. Effectiveness of an early intervention on infant feeding practices and “tummy time”. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(8):701.

Wen LM, Rissel C, Xu H, Taki S, Buchanan L, Bedford K, et al. Effects of telephone and short message service support on infant feeding practices, “tummy time,” and screen time at 6 and 12 months of child age. JAMA Pediatr. 2020.

Ekambareshwar M, Taki S, Mihrshahi S, Baur LA, Rissel C, Wen LM. Participant experiences of an infant obesity prevention program delivered via telephone calls or text messages. Healthcare. 2020;8(1):60.

Jiang H, Li M, Wen LM, Baur LA, He G, Ma X, et al. A short message service intervention for improving infant feeding practices in Shanghai, China: planning, implementation, and process evaluation. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018;6(10):e11039.

Hmone MP, Li M, Agho K, Alam A, Dibley MJ. Factors associated with intention to exclusive breastfeed in central women’s hospital, Yangon, Myanmar. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1).

Lunn PL, Roberts S, Spence A, Hesketh KD, Campbell KJ. Mothers’ perceptions of Melbourne InFANT program: informing future practice. Health Promot Int. 2016;31(3):614–22.

Litterbach EK, Russell CG, Taki S, Denney-Wilson E, Campbell KJ, Laws RA. Factors influencing engagement and behavioral determinants of infant feeding in an mHealth program: qualitative evaluation of the growing healthy program. Jmir Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(12) PubMed PMID: WOS:000419159800012.

Guell C, Whittle F, Ong KK, Lakshman R. Toward understanding how social factors shaped a behavioral intervention on healthier infant formula-feeding. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(8):1320–9.

Ekambareshwar M, Mihrshahi S, Wen LM, Taki S, Bennett G, Baur LA, et al. Facilitators and challenges in recruiting pregnant women to an infant obesity prevention programme delivered via telephone calls or text messages 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. Trials. 2018;19(1).

Matvienko-Sikar K, Toomey E, Delaney L, Harrington J, Byrne M, Kearney PM. Effects of healthcare professional delivered early feeding interventions on feeding practices and dietary intake: a systematic review. Appetite. 2018;123:56–71.

Laws R, Campbell KJ, Van Der Pligt P, Russell G, Ball K, Lynch J, et al. The impact of interventions to prevent obesity or improve obesity related behaviours in children (0–5 years) from socioeconomically disadvantaged and/or indigenous families: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):779.

Graves N, Barnett AG, Halton KA, Veerman JL, Winkler E, Owen N, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a telephone-delivered intervention for physical activity and diet. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e7135.

Hesketh K, Campbell K. Interventions to prevent obesity in 0–5 year olds: an updated systematic review of the literature. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(n1s):S27–35.

Matvienko-Sikar K, Toomey E, Delaney L, Flannery C, McHugh S, McSharry J, et al. Behaviour change techniques and theory use in healthcare professional-delivered infant feeding interventions to prevent childhood obesity: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2019;13(3):277–94.

Badawy SM, Kuhns LM. Texting and mobile phone app interventions for improving adherence to preventive behavior in adolescents: a systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017;5(4):e50.

Partridge SR, Raeside R, Singleton A, Hyun K, Redfern J. Effectiveness of text message interventions for weight management in adolescents: systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020;8(5):e15849.

Turner T, Spruijt-Metz D, Wen CKF, Hingle MD. Prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity using mobile and wireless technologies: a systematic review. Pediatr Obes. 2015;10(6):403–9.

Steckler AB, Linnan L. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002.

Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Cooper C, et al. Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: the need for guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(2):101–2.

Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2009.

Bauman A, Nutbeam D. Evaluation in a nutshell. North Ryde: McGraw-Hill Education Australia; 2013.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Sydney librarian, Ms. Bernadette Carr for assistance in refinement of search terms during set up of the database search strategy. The authors of the original research studies included in this review.

Funding

ME is a PhD scholar funded by the University of Sydney Postgraduate Award scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ME conducted all searches, interpreted results, wrote the first draft of the protocol and manuscript. ME and SE independently screened titles and abstracts, SM was the third reviewer. LAB, CR, RL, SM, LMW, ST and SE contributed to the protocol development and interpretation of the results. All authors provided comments, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary file 1 Assessment of evidence for process evaluation or satisfaction within studies. Supplementary file 2 Assessment of qualitative studies against the COREQ tool. Supplementary file 3 Assessment of qualitative studies against the SRQR tool. Supplementary file 4 PRISMA checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ekambareshwar, M., Ekambareshwar, S., Mihrshahi, S. et al. Process evaluations of early childhood obesity prevention interventions delivered via telephone or text messages: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 18, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01074-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01074-8