Abstract

Background

Respiratory Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic (RMTAC) is an initiative by the Ministry of Health (MOH) Malaysia to improve patients’ medication adherence, as an adjunct to the usual physician care (UC). This study aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of combined strategy of RMTAC and UC (RMTAC + UC) vs. UC alone in asthma patients, from the MOH Malaysia perspective.

Methods

A lifetime horizon dynamic adherence Markov model with monthly cycle was developed, for quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained and hospitalization averted outcomes. Transition probabilities of composite asthma control and medication adherence, utilities, costs, and mortality rates due to all causes were measured from local data sources. Effectiveness, exacerbation rates, and asthma mortality rates were taken from non-local data sources. One-way sensitivity analysis (SA) was conducted for assessing parameter uncertainties, whereas probabilistic SA (PSA) was conducted on a different set of utilities and effectiveness data. Costs were adjusted to 2014 US dollars ($). Both costs and benefits were discounted at a 3% rate annually.

Results

RMTAC + UC was found to be a dominant alternative compared to UC alone; $− 13,639.40 ($− 109,556.90 to $104,445.54) per QALY gained and $− 428.93 ($− 521.27 to ($− 328.69)) per hospitalization averted. These results were found to be robust against changes in all parameters except utilities in the one-way SA, and for both scenarios in PSA.

Conclusions

RMTAC + UC is more effective and yet cheaper than UC alone, from the MOH perspective. For the benefit of both MOH and patients, RMTAC is thus recommended to be remained, and expanded to more healthcare settings where possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma is a heterogeneous chronic respiratory disease that is usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation. Various pharmacological and non-pharmacological asthma managements have been developed to help patients achieve good symptom control and reduce future risk of exacerbation. Medication adherence is one of the most common factors of having poor asthma control [1]. In a survey across 14 countries, the median adherence rate for asthma patients is only 67% [2]. Non-adherence has been proven to worsen asthma control [3], increase risk of future exacerbation [4, 5], and increase asthma-related mortality rate [6]. These can adversely affect the society (patients themselves, healthcare payer, healthcare provider, employer, and other related parties) from both clinical and economics perspectives.

Acknowledging the importance of medication adherence, the Ministry of Health (MOH) Malaysia has initiated a pharmacist-managed Respiratory Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic (RMTAC) in public healthcare facilities. Targeted at non-adhered patients through individual-tailored non-pharmacological management, RMTAC is an adjunct to the usual care (UC) clinic, where physicians in specialist clinic see patients on routine appointments and focussed much lesser on non-pharmacological management. A comparison between RMTAC and UC is detailed in Table 1. Despite being initiated since year 2008, there is lack of information regarding its efficiency. Using modelling method, this study aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of combined strategy of RMTAC and UC (RMTAC + UC) vs. UC alone in asthma patients, from the MOH Malaysia (major public healthcare provider and payer) perspective.

Methods

Model overview

The cohort in the model was 50-year old asthma patients with poorly controlled and/or low adherence with at least a prescribed inhaled corticosteroid and a short-acting beta agonist for the last 3 months, regardless of their phenotypes. The chosen starting age was based on the mean age of the sampled RMTAC cohort from a local public hospital. Those under RMTAC + UC were recruited into RMTAC during month 1, followed up 3 monthly till month 16, and thereafter biannually. The outcome measures were expressed in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and number of hospitalizations. Costs and benefits were discounted at 3% per annum [8]. All costs were adjusted to 2014 US dollars ($1 = Malaysian Ringgit 3.22) [9, 10]. RMTAC was considered cost-effective if the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was below the Malaysian society threshold of $9,006 per QALY gained [7]. This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-12-372-11920).

Model structure

It was decided to develop a new model although there were a few existing Markov models in the literature. This was because the existing models did not adequately consider medication adherence; adherence was commonly incorporated externally by examining different scenarios [11] or making assumptions [12, 13]. These approaches, however, lack the flexibility to directly capture adherence change frequently observed in practice. Consequently, there will be differences in the outcomes that can lead to different decision being made when the model resembles closer to real-world situation [14].

Therefore, a Markov cohort model that incorporated adherence dynamically was developed using Microsoft® Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, United States of America) (Fig. 1). This type of model was chosen because asthma is a chronic disease characterized by recurrence of events, and it can model future outcomes in a longer time horizon [15]. The differences in duration of acute asthma exacerbation and hospitalization do not make any real differences in transition probabilities; hence the cycle length is 1 month. As asthma is a lifelong disease, the model followed patients till they were dead or reached the age of 105 years.

A dynamic adherence Markov cohort asthma model. The model was developed using Microsoft® Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, United States of America). The simulated cohort enters from either one of the three asthma control-adherence states (B, C, and D). Then after a cycle length of 1 month, they either transit to other health states or remain in the current state. There are two absorbing states here, death due to asthma and other causes. The one-way arrow indicates a single direction of transition from one state to the other, whilst the two-way arrow indicates that transition to and fro between two states is possible. The curved arrow indicates that the simulated cohort remains in the current state after a cycle

There were eight health states in this model. Medication adherence was explicitly joined with the asthma control as a composite input of effectiveness. Medication adherence was not combined with the exacerbation states in this model because the latter was a direct effect of the combination between asthma control and medication adherence, which was the beginning state of the model. The hypothetical cohort began either from state B (good control-low adherence), C (poor control-high adherence), or D (poor control-low adherence). The cohort might die due to asthma (state G) when they transited into acute exacerbation [state E (urgent or emergency visit) or F (hospitalization)] from their current state. Although there were chances that they might die due to exacerbation before they could reach any healthcare facility on time, the risk is low and non-significant [16, 17].

This model has four assumptions. First, for simplicity sake, the model assumed that asthma exacerbations severity is mutually exclusive although it was possible for a patient to have more than one type of exacerbation in one cycle time. Secondly, although asthma control might not immediately improved to good level, the medication adherence level was assumed to be high once recovered from exacerbation especially if the exacerbation was triggered by external agents such as polluted air instead of medication non-adherence. Nevertheless, for exacerbation events due to poor medication adherence, the mean adherence level was good at 2 weeks after hospital discharge [18]. Third, the cohort’s pharmacological management and existing co-morbidities issues were assumed to be well managed and treated, which otherwise might pose a ‘false negative’ impact of an existing non-pharmacological intervention. Fourth, it was assumed that the RMTAC + UC cohort had RMTAC follow-up until they die.

Parameter input

Transition probabilities

The transition probabilities between states A–D were calculated from RMTAC patient records of a local public hospital. Data on asthma control (assessed by Asthma Control Test® (ACT)) and medication adherence (assessed by Modified Morisky Adherence Scale 8-Item) were collected from the records for this purpose. In this model, an ACT score of 19 and below defined poor asthma control, whereas an adherence score of below 6 defined low adherence level. The sample size was considered small relative to the true number of RMTAC records in that hospital over 8 years, mainly because two different versions of medication adherence tool had been used and their scores were not interchangeable; hence only RMTAC records that used the latest version of adherence tool were accounted for. Two methods were used to calculate the transition probabilities: (1) a simple and straightforward method for the observed 1-month transition probabilities (N = 16) and (2) a matrix algebra method for the others (N = 52) to predict 1-month transition probabilities as there were insufficient observed 1-month transition probabilities. For resulted value of zero even after both observed and predicted transition probabilities were combined, an addition of one to all observed transition counts as an uninformative prior (according to Bayesian theory) [19] was done prior to recalculating the probabilities for those transitions in that state.

Due to data feasibility issue, it was not possible to collect data for transition probabilities between states A–D under UC arm. Given that the effectiveness of RMTAC + UC vs. UC in improving medication adherence and/or asthma control was unknown, published literatures on similar pharmacist intervention were sought. There was no known literature that studied on both outcomes as a composite. Only one study that published effectiveness data on medication adherence, but as a secondary outcome [20]. Therefore, an effectiveness data on asthma control (as the primary outcome) from a study based on community pharmacists in Australia was employed; the odds of a pharmacist intervention that can result in good asthma control is three times more likely than without intervention (OR 3.06 (95% CI 1.63–5.73)) [21]. This data was first converted to relative risk [22] before applying to the respective transition probabilities calculated for RMTAC + UC arm to obtain the transition probabilities between states A–D under UC arm.

The probabilities of good and poor asthma control patients to get an exacerbation were obtained from an American observational study (N = 2942) [23], assuming that a zero score for Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire meant good control whilst ≥ 1 score meant poor control, and that the adherence level in that study population was low. The probability calculated for state E was made up of that study’s data on both oral steroid bursts and Emergency Department (ED) visits, whereas that for state F was made up of data on hospitalizations. On the other hand, the risks of exacerbation in high adherence level patients stratified by asthma control level were obtained from an American observational study (N = 298) [5] and converted to probabilities [24], assuming that high adherence level was 76%–100% administration of prescribed inhaled corticosteroids and that risk referred to both types of exacerbation i.e. states E and F. The probabilities of achieving good and poor asthma control after an exacerbation were obtained from an American cross-sectional study (N = 2250) [25], assuming that 0–2 dispensing of short acting beta-agonist inhalers per year was good asthma control level, and that unscheduled visits meant both oral steroid bursts and ED visits. The probability of having an exacerbation after another was obtained from an observational study (UK population; N = 211,807) [26], assuming that it was equal for both states E and F. The probability of mortality following exacerbation in state E was obtained from a Spanish observational study by Morell et al. [27]. The age-stratified data on the mortality following exacerbation in state F was obtained from an American observational study (N = 65,831) [28]. The age-stratified data on the mortality due to all causes was obtained from the Malaysian Statistics Department [29]. Where appropriate, the monthly transition probabilities were calculated by using the formula p = 1 − e−rt [30] where p is the monthly probability, r is the monthly rate, and t is the duration of 1 month.

Table 2 shows the transition probabilities as inputs of the model.

The methods of calculating the transition probabilities are detailed in Additional files 1 and 2.

Utilities

The utilities for states A–F (Table 2) were obtained from a local study and measured using standard gamble method [31]. The utility for “well controlled asthma” and “poor controlled asthma” corresponded to states A–D, whereas utility for “severe exacerbation with urgent or ED visit”, and “severe exacerbation with hospitalization” corresponded to states E and F, respectively. The measured utilities here considered asthma control alone; although medication adherence is expected to affect the health-related quality of life, its association with the latter is inconsistent [32,33,34,, 33, 3435]. Hence, the utilities for states A and C were assumed to be the same for states B and D, respectively.

Costs

The unit costs of maintenance (states A–D), acute (state E), and hospitalization (state F) events were obtained from a local study and measured using activity-based micro-costing approach [36]. The unit costs of states A–D were prorated monthly according to the frequency of visits annually, as suggested by clinical experts; states A (6 monthly), B (4 monthly), C (2 monthly), and D (3 monthly) (Table 2). Using the same methods [36], the unit costs of RMTAC at recruitment and follow-up stages (Table 2) were measured. The resources involved were time spent by personnel, fixed assets, maintenance of the room, and consumables.

Validation

The model was externally validated by comparing the life years in the simulated cohort with the national life expectancy of a 50 year old [37]. The life expectancy of both asthmatics and non-asthmatics were considered to be similar because the mortality due to all causes of asthma patients was found to have a non-significant age, smoking, social and medical confounders-adjusted hazard ratio when compared against non-asthmatics in a prospective study [38].

Sensitivity analysis

One-way sensitivity analysis was performed on all parameters, within their 95% confidence intervals or an arbitrary range of ± 20% if confidence intervals were unavailable. The discount rate was also varied with 0% and 5%. The confidence intervals for the transition probabilities between states A–D were calculated using Wilson’s method [39].

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) with 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations was performed to address three uncertainties. First was the parameter uncertainty on the base case. Second, the effectiveness data on asthma control in the base case was replaced with that on medication adherence; OR of 1.89 (95% CI 1.08–3.30) [20]. Third, the utilities in the base case were replaced with a different set of utilities measured from a bigger sample size; utilities were measured using the same methods [31] on another sample of subjects (N = 24) and combined with those used in the base case. However, repeated measures of the utility for poor asthma control (states C and D) was not possible due to illogical consistency findings in the study [31] which has yet to be further explored; hence, the utilities used in base case for these states remained in PSA. The inputs for the second and third PSA scenario are as in Table 2. The results of PSA were expressed in incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) (95% credible intervals (CI)).

Results

Base-case analysis

The results for base-case analysis are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 2a, b. The number of life years was similar between RMTAC + UC and UC. It was also very close to the national life expectancy of a 50 year old i.e. 27.8 years [37], hence confirming the external validity of the model. With an incremental cost of $− 2409.86 ($− 4454.42 to ($− 841.22)), the mean number of QALY gained was 0.18 (− 0.45 to 0.83), whilst that of hospitalization averted was 5.62 (2.19–9.92) (these incremental data is not shown in table). Overall, RMTAC + UC was found to be a dominant alternative compared to UC alone for both QALY gained and hospitalization averted outcomes.

Results of probabilistic sensitivity analysis. This figure shows the results of Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis on base-case (a and b), effectiveness factormedication adherence (c and d), and a different set of utilities (e). The results are expressed in incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (95% credible intervals).

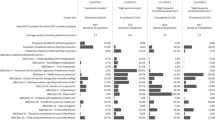

One-way sensitivity analysis

The base-case results were found to be robust with all parameters varied within their range, except for the lower limit of utility of states A and B and the upper limit of utility of states C and D (Fig. 3a, b). In those two situations, RMTAC + UC was not considered as a cost-effective alternative compared to UC alone. These were expected as the lower limit of utility of states A and B was lower than the base-case utility of poor asthma control i.e. states C and D; hence the ICER increased to $12,955 per QALY gained. On the other hand, the upper limit of utility of states C and D was higher than the base-case utility of good asthma control i.e. states A and B; hence the ICER increased to $28,614 per QALY gained.

Results of one-way sensitivity analysis. The figures show the results of one-way sensitivity analysis for base-case ICER per QALY gained (a) and hospitalization averted (B) outcomes. The parameters involved correspond to those listed in Table 2. The width of the bars indicates the extent of variation of the base-case ICER due to change in one parameter at a time

Scenario analyses

The results of scenario analyses using PSA were found to be in a similar fashion as the base-case results (Fig. 2c–e). RMTAC + UC remained to be a dominant alternative compared to UC alone in both scenarios. The ICERs were higher than the ICER of base-case. At a lower effectiveness level, the mean QALY gained was 0.08 whilst a mean of 2 hospitalizations were averted. By contrast, at a lower set of utilities of exacerbations, the mean QALY gained was 0.30.

Discussion

This study had shown that having pharmacist intervention (RMTAC) as an adjunct to clinical respiratory clinic (UC) was a cheaper and yet more effective alternative than UC alone in terms of QALY and hospitalizations.

Parameter inputs other than the transition probabilities between states A–D, utilities, and costs were from non-local sources due to lack of local data, hence there may be transferability issues. The two effectiveness factors originated from different countries i.e. Spain [21] and Australia [20]. Nevertheless, the characteristics of their interventions are deemed similar to RMTAC management because the pharmacists in those studies were trained prior to intervention, and conducted assessments and adjustments according to an individual needs on asthma control, medication adherence, and inhaler technique, gave education to patients regarding disease and medication issues; these tasks are almost, if not equally, identical to the RMTAC pharmacists’ tasks on every patient visit. Parameters obtained from observational studies that originated from United Kingdom (UK) and Spain were more readily transferable than US to Malaysia’s setting; data on mortality and exacerbations from UK and Spain have less impact on transferability issue because their extent of accessibility and affordability to healthcare services [40, 41] is similar to that in Malaysia. However, given that the accessibility and affordability in US is poor [40, 42], data on exacerbation and mortality rates from US observational studies are likely to be biased upwards in Malaysia setting; hence the ICERs in this study could be underestimated.

In this model, the same set of utilities was used for both arms. Although one might argue that RMTAC patients could have higher preferences for those health states than those who were not, similar studies have shown that there were no significant differences in the utilities between the intervention and control groups [43,44,44,44,45]. Therefore, data were collected from asthma patients regardless of their RMTAC treatment history.

The ICER per QALY gained in the base-case and scenario analyses seemed to be driven by the cost savings more than the QALY gained itself because of the small incremental of QALY between the two arms despite using two different sets of utilities. This could be explained by the insignificant difference between the good and poor asthma control utilities that were used as model inputs for states A–D. It is hypothesised that if the utility of poor asthma control is significantly lower than the utility of good asthma control, the incremental QALY will be larger. As such, the current ICERs could have been overestimated given the cost savings.

No direct comparison could be made with other literatures in terms of the base-case results, as there were no economic evaluations that assessed the efficiency of non-pharmacological asthma managements for a lifetime horizon [46]. Nevertheless, there was a 5-year study that demonstrated dominance of integrated care between respiratory nurse specialists, general physicians, and respiratory consultants [47]. Although the intervention is different than RMTAC, it still shows that asthma patients benefited from long-term enhanced management by gaining QALYs. No studies are known to have used hospitalization as outcome measure, however.

There are some limitations in this study. First, the monthly transition probabilities between states A–D were calculated from a small sample size (N = 68). Due to feasibility issue, data could not be collected from more than one public site to increase the sample size. As there were less than 20 observed monthly transitions, two methods were used to make the best out of all available observed transitions. Consequently, most of the probabilities had high uncertainties due to using non-monthly transitions to predict monthly transition probabilities. Despite this, the base-case ICER was found to be robust even when this parameter was varied within the upper and lower limits. Secondly, the modelled health states A, B, C, and D are made up of both asthma control and medication adherence elements. Ideally the treatment effect should be a composite of those elements. Due to lack of such data, individual effectiveness factor (asthma control) was used in the base case analysis instead and another (medication adherence) in the scenario analysis. The results from those analyses were similar; hence it seemed that there will not be a substantial difference in the ICER if a composite treatment effect even if it is necessary. Third limitation of the current study is that a Value-of Information analysis was not done to determine if the evidences used to build this model is sufficient and whether it is worth the money for further researches to be done given the uncertainties in the results, which ultimately affects the decision made by the health policymaker [48].

Conclusions

Using a new lifetime Markov model that dynamically incorporates medication adherence, this study concludes that RMTAC + UC is a dominant alternative compared to UC alone from the MOH Malaysia perspective. For the benefit of both MOH and patients, RMTAC is thus recommended to be remained, and expanded to more healthcare settings where possible. It is suggested that data regarding effectiveness of RMTAC to be collected from more public healthcare settings in the future; the findings will be useful to address the uncertainties posed by the monthly transition probabilities between states A–D calculated here.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

credible interval

- ICER:

-

incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- MOH:

-

Ministry of Health

- PSA:

-

probabilistic sensitivity analysis

- QALY:

-

quality-adjusted life year

- RMTAC:

-

Respiratory Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic

- UC:

-

usual care

References

Haughney J, Price D, Kaplan A, et al. Achieving asthma control in practice: understanding the reasons for poor control. Respir Med. 2008;102(12):1681–93.

DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42(3):200–9.

Armour CL, Reddel HK, LeMay KS, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of an evidence-based asthma service in Australian community pharmacies: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. J Asthma. 2013;50(3):302–9.

Suissa S, Ernst P, Kezouh A. Regular use of inhaled corticosteroids and the long term prevention of hospitalisation for asthma. Thorax. 2002;57(10):880–4.

Williams LK, Peterson EL, Wells K, et al. Quantifying the proportion of severe asthma exacerbations attributable to inhaled corticosteroid nonadherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(6):1185–91.

Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, Baltzan M, Cai B. Low-dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(5):332–6.

Shafie AA, Lim YW, Chua GN, Hassali MA. Exploring the willingness to pay for a quality-adjusted life-year in the state of Penang, Malaysia. ClinicoEcon Outcomes Res. 2014;6:473–81.

Pharmaceutical Services Division. Pharmacoeconomic Guideline for Malaysia. Putrajaya: Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2012.

Central Bank of Malaysia. Exchange rates 2014. Rates & statistics 2016. http://www.bnm.gov.my/. Accessed 24 Feb 2016.

World Development Indicators. Health expenditure per capita (current US$). 2016. http://data.worldbank.org. Accessed 8 May 2016.

Zafari Z, Lynd LD, FitzGerald JM, Sadatsafavi M. Economic and health effect of full adherence to controller therapy in adults with uncontrolled asthma: a simulation study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):908–15.

Dewilde S, Turk F, Tambour M, Sandström T. The economic value of anti-IgE in severe persistent, IgE-mediated (allergic) asthma patients:adaptation of INNOVATE to Sweden. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(9):1765–76.

Campbell JD, Spackman DE, Sullivan SD. The costs and consequences of omalizumab in uncontrolled asthma from a USA payer perspective. Allergy. 2010;65(9):1141–8.

Slejko JF, Sullivan PW, Anderson HD, Ho PM, Nair KV, Campbell JD. Dynamic medication adherence modeling in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a Markov microsimulation methods application. Value Health. 2014;17(6):725–31.

Roberts M, Russell LB, Paltiel AD, Chambers M, McEwan P, Krahn M. Conceptualizing a model: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-2. Med Decis Making. 2012;32(5):678–89.

Jones AP, Bentham G. Health service accessibility and deaths from asthma in 401 local authority districts in England and Wales, 1988–1992. Thorax. 1997;52(3):218–22.

Jones AP, Bentham G, Horwell C. Health service accessibility and deaths from asthma. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(1):101–5.

Smith A, Krishnan JA, Bilderback A, Riekert KA, Rand CS, Bartlett SJ. Depressive symptoms and adherence to asthma therapy after hospital discharge. Chest. 2006;130(4):1034–8.

Price MJ, Briggs AH. Development of an economic model to assess the cost effectiveness of asthma management strategies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20(3):183–94.

Armour C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Brillant M, et al. Pharmacy Asthma Care Program (PACP) improves outcomes for patients in the community. Thorax. 2007;62(6):496–502.

Garcia-Cardenas V, Sabater-Hernandez D, Kenny P, Martinez-Martinez F, Faus MJ, Benrimoj SI. Effect of a pharmacist intervention on asthma control. A cluster randomised trial. Respir Med. 2013;107(9):1346–55.

Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;280(19):1690–1.

Sullivan SD, Wenzel SE, Bresnahan BW, et al. Association of control and risk of severe asthma-related events in severe or difficult-to-treat asthma patients. Allergy. 2007;62(6):655–60.

Spruance SL, Reid JE, Grace M, Samore M. Hazard ratio in clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(8):2787–92.

Schatz M, Zeiger RS, Vollmer WM, Mosen D, Cook EF. Determinants of future long-term asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(5):1048–53.

Suruki RY, Daugherty JB, Boudiaf N, Albers FC. The frequency of asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization in patients with asthma from the UK and USA. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17:74.

Morell F, Genover T, Munoz X, Garcia-Aymerich J, Ferrer J, Cruz MJ. Rate and characteristics of asthma exacerbations: the ASMAB I study. Arch Bronconeumol. 2008;44(6):303–11.

Krishnan V, Diette GB, Rand CS, et al. Mortality in Patients Hospitalized for Asthma Exacerbations in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(6):633–8.

Department of Statistics Malaysia. Vital Statistics Malaysia 2012. Putrajaya 2013.

Fleurence RL, Hollenbeak CS. Rates and probabilities in economic modelling: transformation, translation and appropriate application. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(1):3–6.

Yong YV, Shafie AA. Development, feasibility, and validity of a computer-based utility assessment tool for measuring asthma-specific health utilities in Malaysia using the standard gamble method. J Asthma. 2016;6:1–8.

Bender BG, Apter A, Bogen DK, et al. Test of an interactive voice response intervention to improve adherence to controller medications in adults with asthma. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(2):159–65.

Joshi AV, Madhavan SS, Ambegaonkar A, Smith M, Scott VG, Dedhia H. Association of medication adherence with workplace productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with asthma. J Asthma. 2006;43(7):521–6.

Small M, Anderson P, Vickers A, Kay S, Fermer S. Importance of inhaler-device satisfaction in asthma treatment: real-world observations of physician-observed compliance and clinical/patient-reported outcomes. Adv Ther. 2011;28(3):202–12.

Takemura M, Kobayashi M, Kimura K, et al. Repeated instruction on inhalation technique improves adherence to the therapeutic regimen in asthma. J Asthma. 2010;47(2):202–8.

Yong YV, Shafie AA. How much does management of an asthma-related event cost in a Malaysian Suburban Hospital? Value Health Reg Issues. 2018;15:6–11.

Department of Statistics Malaysia. Abrigded life tables Malaysia 2009–2011. Putrajaya 2012.

Huovinen E, Kaprio J, Vesterinen E, Koskenvuo M. Mortality of adults with asthma: a prospective cohort study. Thorax. 1997;52(1):49–54.

Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):857–72.

Blendon RJ, Schoen C, DesRoches CM, Osborn R, Scoles KL, Zapert K. Inequities in health care: a five-country survey. Health Aff. 2002;21(3):182–91.

García-Sánchez I, Tirado MC. Quality in and equality of access to Healthcare Services. Spain: European Commission; 2008.

Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM. Access, affordability, and insurance complexity are often worse in the United States compared to ten other countries. Health Aff. 2013;32(12):2205–15.

Gordois A, Armour C, Brillant M, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a pharmacy asthma care program in Australia. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2007;15(6):387–96.

Schermer T, Thoonen B, van den Boom G, et al. Randomized controlled economic evaluation of asthma self-management in primary health care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1062–72.

van der Meer V, van den Hout WB, Bakker MJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of internet-based self-management compared with usual care in Asthma. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e27108.

Yong YV, Shafie AA. Economic evaluation of enhanced asthma management: a systematic review. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(4):15.

Steuten L, Palmer S, Vrijhoef B, Van Merode F, Spreeuwenberg C, Severens H. Cost-utility of a disease management program for patients with asthma. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23(2):184–91.

Claxton K, Eggington S, Ginnelly L, et al. A Pilot Study of Value of Information Analysis to Support Research Recommendations for the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Centre for Health Economics, University of York; 2005.

Authors’ contributions

YYV collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data regarding economic evaluation and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. AAS provided guidance in the whole process of economic evaluation, reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Professor Henry Glick of University of Pennsylvania provided support and guidance in calculating transition probabilities for composite asthma control and medication adherence Health states. Professor David Price of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute provided invaluable support in providing resources for some of the data input model.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-12-372-11920).

Funding

These findings are the result of work supported by the Ministry of Health Malaysia. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and no official endorsement by the Ministry of Health is intended or should be inferred. Funding was provided by the Ministry of Health Malaysia (Grant No. 01426).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Appendix S1.

Calculation of transition probabilities

Additional file 2: Appendix S2.

Calculation of transition probabilities for health states A – D of RMTAC + UC arm

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yong, Y.V., Shafie, A.A. Using a dynamic adherence Markov model to assess the efficiency of Respiratory Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic (RMTAC) on asthma patients in Malaysia. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 16, 36 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-018-0156-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-018-0156-1