Abstract

Background

Evidence on the relative costs and effects of interventions that do not consider ‘real-world’ constraints on implementation may be misleading. However, in many low- and middle-income countries, time and data scarcity mean that incorporating health system constraints in priority setting can be challenging.

Methods

We developed a ‘proof of concept’ method to empirically estimate health system constraints for inclusion in model-based economic evaluations, using intensified case-finding strategies (ICF) for tuberculosis (TB) in South Africa as an example. As part of a strategic planning process, we quantified the resources (fiscal and human) needed to scale up different ICF strategies (cough triage and WHO symptom screening). We identified and characterised three constraints through discussions with local stakeholders: (1) financial constraint: potential maximum increase in public TB financing available for new TB interventions; (2) human resource constraint: maximum current and future capacity among public sector nurses that could be dedicated to TB services; and (3) diagnostic supplies constraint: maximum ratio of Xpert MTB/RIF tests to TB notifications. We assessed the impact of these constraints on the costs of different ICF strategies.

Results

It would not be possible to reach the target coverage of ICF (as defined by policy makers) without addressing financial, human resource and diagnostic supplies constraints. The costs of addressing human resource constraints is substantial, increasing total TB programme costs during the period 2016–2035 by between 7% and 37% compared to assuming the expansion of ICF is unconstrained, depending on the ICF strategy chosen.

Conclusions

Failure to include the costs of relaxing constraints may provide misleading estimates of costs, and therefore cost-effectiveness. In turn, these could impact the local relevance and credibility of analyses, thereby increasing the risk of sub-optimal investments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Frameworks for priority setting for the control of infectious diseases in low-and middle-income countries are evolving. In recent years, mathematical models of disease transmission have been increasingly used for supporting priority setting efforts in these settings [1,2,3]. At the same time, the importance of considering both supply-side and demand-side constraints on the uptake, delivery and cost-effectiveness of global health interventions has been widely recognised [4, 5]. Understanding constraints is particularly relevant in low and middle-income countries, where non-financial constraints such as human resources scarcity may substantially impact the feasibility of implementation and pace of scale-up of interventions [6, 7]. Traditionally, model-based priority setting has incorporated and adapted to local demographic and epidemiological characteristics, but to date the explicit consideration of the impact of context-specific health system constraints on the costs and cost-effectiveness of global health interventions is often absent [8].

Several approaches have been proposed for incorporating both financial and non-financial resource constraints in model-based priority setting for infectious diseases. These allow the analyst to either restrict outputs to limit the impact of interventions, or to cost the relaxation of constraints. For limiting impact, some have adopted an ‘integrated modelling’ approach combining disease and operational (health systems) modelling. However, this approach has substantial data requirements as detailed knowledge of numerous processes across the health system is necessary to populate the operational model [9, 10]. Another approach is mathematical programming, which examines solutions that maximise global health objectives under a range of constraints [11]. Mathematical programming has the advantage of potentially dealing simultaneously with multiple constraints, such as equity and efficiency [12,13,14]. However, combining this approach with infectious disease models is computationally complex and data-intensive [14]. While mathematical programming has the potential to be widely applied in the presence of strengthened health information systems, the ‘black box’ nature of this approach may constitute a barrier for users and result in a process that lacks transparency for decision-makers [15].

A gap remains for approaches to support decision-makers set priorities that assess the impact of constraints and that are feasible within planning timeframes and under considerable data scarcity. In this context, we present a proof of concept for a pragmatic method for the empirical estimation of both financial and non-financial constraints from routine data. Target users are analysts involved in priority setting to support national strategic planning processes, who wish to explicitly model the impact of selected constraints. This method was developed and piloted during the policy planning process for the 2017–2022 National Tuberculosis Plan (NTP) in South Africa, rather than in a research setting. We illustrate the approach in respect of facility-based tuberculosis (TB) case-finding strategies. Specifically, we present methods for estimating financial, human resource and diagnostic constraints, and demonstrate how these can be used in estimating the costs of the facility-based TB case finding strategies under constraints.

Methods

Study setting

South Africa faces one of the world’s worst TB epidemics [16]. TB programmes often rely on passive case-finding, focused on the screening of individuals presenting to health facilities with TB symptoms. This method has been shown to miss a large proportion of facility-based TB cases presenting with unrelated symptoms [17]. In 2015, Intensified Case Finding (ICF) for TB was adopted in South Africa for detecting TB cases among HIV-infected health facility attendees, who are screened for TB at each facility visit. During the previous year, the South African TB Think Tank was established with the purpose of advising the National Department of Health (NDoH) on TB policy and strategic planning [18]. As part of this effort, an economic analysis to identify the optimal ICF and TB diagnostic strategy for South Africa was conducted. The ICF programme would be targeting over 100 million visits to primary health care facilities per year.

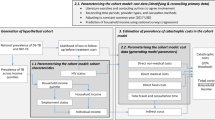

Identifying and characterising constraints

The analysis concentrated on supply-rather than demand-side constraints. The process of constraints estimation is described in Fig. 1. Three constraints on health system resources relevant to TB service provision were identified through discussions with local stakeholders that primarily took place as part of the TB Think Tank meetings (NDoH TB programme managers and staff, technical assistants and local TB experts supporting the national planning processes). Stakeholders were selected based on their participation in the TB Think Tank. Individual discussions were held with 12 Think Tank members and group discussions were facilitated during Think Tank meetings, attended by an average of 25 stakeholders. In the context of policy meetings, no formal interview process was used. In addition to financial constraints, stakeholders consistently highlighted human resource and supplies constraints and agreed for these to be considered in the analysis.

Financial constraint

We conducted a fiscal space analysis for estimating the financial constraint for TB. Baseline levels of total public expenditure on TB were estimated using the most recent figures (2013) [19]. To convert South African Rand into US Dollars, we used the average official exchange rate over the 3-year period to 2016 (13.9) [20]. For the NTP 2017–2022 period, we used the fiscal space model developed by Remme et al. [21]. This model considers the increase in public spending from GDP growth, health prioritisation within the overall government budget as well as TB prioritisation within overall health spending, earmarked alcohol taxes and efficiency gains.

While in principle resources for TB could be allocated from the general health budget, the budgeting process is historically incremental. We therefore considered three scenarios (Table 1), including one where policy makers do not use all the fiscal space available to them. In the low constraint scenario (most limiting), the TB budget was assumed to grow at an annual rate of 1.7% in line with GDP growth only [21]. This assumes that TB policy makers are unable to advocate for a greater share of the overall health budget. In the medium constraint scenario, we assumed that, between 2017 and 2022, an increased share (from 2 to 15%) of the health budget is allocated to TB to match the share of the burden of disease caused by TB, adjusted for TB mortality as reported by the NDoH (15%). In the high constraint scenario (least limiting), we assumed that 15% of a health budget that achieves its full fiscal space growth (3%) is allocated to TB. In all scenarios we assumed that, post 2022, TB expenditure would continue to grow by a constant rate of 1.7% per annum.

Human resource constraint

In consultation with the NDoH, the constraint on human resources was characterised as the available annual full time equivalent (FTE) of nursing staff to provide all TB services, expressed in minutes of available nursing time. The constraint was applied to all TB services, as increased screening will also increase the use of other TB services along the patient pathway. Nurses are the main cadre of staff that deliver TB case detection, diagnosis and treatment in South Africa. The nursing cadres considered were professional (or registered) nurses, including TB and antiretroviral therapy nurses; and enrolled nurses, who are not specialised and carry out many of the same activities as registered nurses but do not prescribe drugs. The analysis was limited to nurse availability in primary health care (PHC) clinics and health centres.

The total FTE spent by nursing staff on TB in 2015 (baseline) was estimated from routine data available upon request (DHIS, Persal, Electronic TB Register). In addition, estimates were informed by ongoing or recently concluded costing studies that measured human resource use, published literature and personal communications with the NDoH (see Additional file 1 for further details). Projections on the growth of the nursing workforce in South Africa were informed by historical data available from the South African Nursing Council [22].

Three human resource constraint scenarios were considered (Table 1). For the low (most limiting) constraint, we assumed TB policy-makers are unable to re-allocate nurses from other services. In this case, the maximum annual minutes spent on TB were held at the current level and adjusted in future years based on population growth projections, holding the ratio of nurses trained per capita constant [23]. For the medium and high constraints, nurse time was allocated to TB according to the disease burden (from 6 to 15%) during the NTP period. This was calculated as the ratio of total deaths from TB among HIV-infected and -uninfected patients [24], to total deaths in South Africa [25]. Post 2022, the low and medium constraint increased annually in line with population growth projections. The high (least limiting) constraint also took the historically rapid nursing workforce growth in South Africa into account.

Diagnostic supplies constraint

Strengthening TB case-finding may have a substantial impact on diagnostic supplies requirements and related costs. While South Africa has demonstrated the capacity to rapidly scale up TB diagnostic volumes [26], in consultation with the NDoH we identified a constraint on the amount of TB diagnostic supplies (Xpert MTB/RIF tests) purchased annually. This constraint corresponds to the rule of thumb that has been used to set the TB diagnostic budget in previous years (South African NDoH, personal communication), which limits the TB programme to a ratio of 20 Xpert MTB/RIF tests for every case of TB diagnosed.

Estimating the costs of TB services considering constraints

We estimated TB service costs both under constraints and with relaxing of the constraints using a mathematical model of TB that estimates TB cases, TB mortality and the use of TB services [27]. The model was calibrated for the year 2015 and cost projections were generated for a 20-year period up to 2035. The model was used to calculate costs of introducing nine different ICF intervention options (described in Fig. 2), by multiplying projected TB service volumes by the unit costs for all TB services and interventions.

In detail, the ICF intervention options examined involve screening two different populations (all clinic patients or only those that are HIV-infected) using either cough triage, a single question on whether the respondent has been coughing for at least 2 weeks, or the full WHO symptoms screener, whereby patients reporting either current cough, fever, weight loss or night sweats are referred for TB testing [28]. Unit costs for TB services and interventions in South Africa were derived from previously published data or constructed using ingredients costing, as described in Additional file 1. A discount rate of 3% was applied to future costs.

The model was first used to estimate costs of the ICF interventions in an unconstrained environment, expanding services to coverage levels defined by policy targets (as described elsewhere and in Additional file 1) [27]. Each constraint scenario was then applied independently. When constraints were exceeded, the model was re-run at a reduced coverage, such that the projected costs or (in the case of the human resource constraint) nurse time remained below the constraint over the entire time horizon. For the supplies constraint, coverage was limited once the ratio of diagnostic tests to TB notifications was exceeded. Results on the effects of the constraints on intervention impact and the resulting coverage gaps are described elsewhere by Sumner et al. [27].

Relaxing the Xpert MTB/RIF constraint was assumed to have no costs aside from purchasing and deploying additional tests. Similarly, relaxing the financial constraints results in no additional costs compared to the unconstrained scenario. The additional costs of relaxing the human resource constraint was estimated as the cost of hiring and employing the extra nurses needed to supply the additional number of minutes required for the three constrained scenarios to reach the coverage and output levels achieved under the unconstrained scenario. Our estimations considered a mix of registered (51%) and enrolled (49%) nurses based on DHIS and South African Nursing Council data. In discussion with the NDoH, some of the extra minutes required to relax the constraints were supplied by existing private sector nurses, as the average monthly salary for public sector nurses is higher than that in the private sector [29]. The underlying assumption is that, currently, nurses join the private sector due to a lack of open positions in the better paying public sector. In the first year where the nurse minutes requirements exceeded availability under the constrained scenario, we assumed all minutes worked in primary health care by private sector nurses could be re-allocated to the public sector as needed. In subsequent years, we assumed the historical proportion of new graduates joining the private sector would join the public sector instead. All private sector nurses and nursing graduates were assumed to be registered nurses.

The additional minutes needed to relax the constraints that could not be covered by employing the current private sector workforce were costed by estimating the costs of increasing government-sponsored new graduates. Professional nurses spend a total of 48 months in training while enrolled nurses take 36 months to qualify [30]. Both cadres receive a monthly stipend of US$ 676 from the government to cover living expenses while in training. Once employed, a 10% mark-up on the annual salary of new graduates was factored into take the transaction costs of employment into account. An additional 10% mark-up over basic pay was added for 30% of new nurses, representing the allowance received by those posted in rural areas [31].

Results

Base case estimates of financial, human resources and number of Xpert MTB/RIFs

In 2015, we estimate a public expenditure for the TB programme of approximately U$ 415 million, of which US$ 310 million was spent on direct service provision and the rest on administration and other above-service-level activities. Changes in financial resource requirements for service provision over time in the absence of new interventions are shown in Table 2. The decrease in the costs of TB services over time under this scenario reflects the projected declining trend in the TB epidemic in South Africa.

We estimate that the South African nursing workforce supplied approximately 209.5 million minutes to TB services in public primary health care facilities in 2015. Specialised TB nurses accounted for about 15% of total minutes for TB, while most TB service provision time was supplied by other professional nurses (51%) and enrolled nurses (34%). Figure 3 shows the distribution of staff time across different TB services under the base case, assuming no new intervention is introduced. Finally, the number of Xpert MTB/RIF tests in 2015 was estimated to be 3.2 million.

Constrained scenarios

The low (most limiting) budget and human resource constraints were exceeded by almost all interventions. These constraints were deemed unrealistic to overcome and thus not modelled further, as they made any expansion of case-finding infeasible without substantial disinvestment in other areas of TB care. Conversely, the high budget constraint was never exceeded. The impact of the other constrained scenarios on TB costs between 2016 and 2035 is presented in Fig. 4. Under the medium budget constraint, all case-finding interventions could be ‘afforded’ with the exception of intervention 10 (combination of expanding Xpert MTB/RIF coverage, increasing adherence to the Xpert-negative algorithm and achieving 90% coverage of the WHO symptoms screener among all PHC clinic attendees). Under this scenario, there was a relatively small funding gap of approximately US$ 24.9 million over the period 2016–2035 for intervention 10 (Fig. 4).

2016–2035 budget requirements for interventions at reduced coverage under financial, human resource and Xpert constraints, 2016 US$ (millions). Interventions are described in Fig. 2

The human resource constraints do not impact interventions 2–5 (expanded Xpert MTB/RIF utilisation and increased adherence to the Xpert-negative algorithm, alone or in combination, and cough-based screening among all HIV-infected PHC clinic attendees, respectively). Interventions 6–8 (cough-based screening, both on its own among all PHC attendees and in combination with the strengthening of diagnostic algorithms) are impacted to a limited extent. Implementation of interventions 9 and 10 (combinations of strengthened diagnostic algorithms and ICF using cough triage or the WHO symptoms screener, respectively) is substantially constrained by human resource availability. If this constraint is not addressed, there is a difference in predicted TB costs of more than US$ 4 billion between the unconstrained and medium human resource constraint scenarios over the period 2016–2035 due to the restrictions on the level of TB services that the health system can supply.

The diagnostic supplies constraint restricts the coverage of all interventions, and similarly results in a reduction in costs by limiting access to TB services (Fig. 4).

Costs of relaxing the human resource constraints

The incremental nurse minutes that would be needed to relax the human resource constraints and match the intervention coverage achieved in the unconstrained scenario are presented in Table 3. We found that a maximum of 3.3 million nurse minutes, corresponding to the annual time supplied by approximately 1300 nurses, can be switched from the private to the government sector between 2017, the year in which the National TB Plan case-finding interventions begin rolling out, and 2035. This is sufficient to cover the incremental needs of cough-based screening interventions (6 and 9) under all constrained scenarios, but does not meet the extra demand generated from strengthening the use of the WHO symptoms screener. Achieving 90% ICF coverage would require approximately 15 or 25% of all nurses in the South African public health system to work on TB if using cough triage or the WHO tool, respectively.

The highest costs of relaxing the constraint arise under the medium constraint scenario for intervention 8, aimed at strengthening the use of the WHO symptoms screener among all PHC attendees. The costs of hiring and training a sufficient number of nurses in this scenario between 2017 and 2035 are approximately US$ 3.76 billion (US$ 187.9 million per year on average), corresponding to approximately 60% of the entire financial resource requirements for delivering the baseline TB services during the same period (US$ 316.2 million per year on average).

Discussion

We present a pragmatic approach using routine data and stakeholder opinions, applied in a policy context, that was used to inform decision-makers on the impact of supply-side constraints on ICF for TB in South Africa. We were able to produce estimates of constraints and apply these to TB transmission models to limit attainable service coverage and generate estimates of intervention costs, advancing the work conducted by Hontelez et al. [14], who considered a single, non-empirically defined cost of health systems strengthening. We provide an illustration of the work of Van Baal et al., who recommend that human resource constraints should be considered in economic evaluation to avoid producing biased cost-effectiveness estimates that could mislead decision-makers [15]. In the South African setting we find that, when constraints are considered, substantial additional costs may be incurred to expand TB services, which will impact incremental cost-effectiveness ratios.

Conceptually, the constraints analysed in our approach may be considered as ‘policy’ constraints representing ‘fixity’ in resource use, which is primarily determined by policy choice rather than by the inherent characteristics of the resources. In this sense, our analysis highlighted the costs to TB programme managers of policies around financing and human resource planning. Likewise, our analysis could be used by those planning human resources to help estimate the health impact of those investments. Compared to other modelling approaches used in the literature, our method has relatively limited data requirements and is less computationally intensive than operational modelling [9, 10]. While the results may be less comprehensive and not provide formal optimisation within constraints compared to other methods, they can be used to promote deliberation to redefine the mix of health system strengthening with disease specific activities within intervention strategies.

As a proof of concept conducted in a pragmatic rather than research setting, our analysis has many limitations. Several of these need improvement as the methods are further applied. Firstly, our selection of constraints was informal, both in terms of the identification of stakeholders and of the list of constraints identified. This may underestimate the costs of addressing all constraints. Secondly, we assumed that unit costs and minutes per service remain constant during intervention scale-up and we do not consider the differential impact of constraints at different coverage levels. A third limitation is data quality for some of the routine information systems. For example, DHIS data on the annual hours worked by public sector nurses is not updated every year to reflect staff movements to the private sector, thus potentially overestimating nurse minutes supplied in the government sectors.

Our broad approach (stakeholder identification of constraints, routine data and stakeholder engagement to characterise them, independent application in the model and deliberation) is potentially generalisable to other settings. However, the way it is implemented is likely to be highly dependent on both local data sources and policy processes. In South Africa, formal processes for strategic planning are developing and there is no formal health technology assessment. In other settings, it may be possible to substantially improve both the elicitation and characterisation of constraints. Despite the shortcomings of our ‘proof of concept’ approach, the engagement of stakeholders through the whole process helps ensuring ownership, relevance and usefulness of the analysis. This work was used to inform the National TB Strategy, specifically to refine the staffing of ICF approaches [18, 32]. Moreover, the engagement of stakeholders can lay the foundation for further work to refine and develop the analysis, as iterative decisions are made during intervention scale-up.

References

Houben RMGJ, Lalli M, Sumner T, Hamilton M, Pedrazzoli D, Bonsu F, Hippner P, Pillay Y, Kimerling M, Ahmedov S, et al. TIME impact—a new user-friendly tuberculosis (TB) model to inform TB policy decisions. BMC Med. 2016;14:1–10.

McGillen JB, Anderson S-J, Dybul MR, Hallett TB. Optimum resource allocation to reduce HIV incidence across sub-Saharan Africa: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e441–8.

Menzies NA, Gomez GB, Bozzani F, Chatterjee S, Foster N, Garcia Baena I, Laurence Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness and resource implications of aggressive TB control in China, India and South Africa: a combined analysis of nine models. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e816–26.

Hauck K, Thomas R, Smith PC. Departures from cost-effectiveness recommendations: the impact of health system constraints on priority setting. Health Syst Reform. 2016;2:61–70.

Vassall A, Mangham-Jefferies L, Gomez GB, Pitt C, Foster N. Incorporating demand and supply constraints into economic evaluation in low-income and middle-income countries. Health Econ. 2016;25:95–115.

Gericke CA, Kurowski C, Ranson MK, Mills A. Intervention complexity—a conceptual framework to inform priority-setting in health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:285–93.

Hanson K, Ranson MK, Oliveira-Cruz V, Mills A. Expanding access to priority health interventions: a framework for understanding the constraints to scaling-up. J Int Dev. 2003;15:1–14.

Mikkelsen E, Hontelez JAC, Jansen MPM, Bärnighausen T, Hauck K, Johansson KA, Meyer-Rath G, Over M, de Vlas SJ, van der Wilt GJ, et al. Evidence for scaling up HIV treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a call for incorporating health systems constraints. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002240.

Langley I, Lin H, Egwaga S, Doulla B, Ku C, Murray M, Cohen T, Squire SB. Assessment of the patient, health system, and population effects of Xpert MTB/RIF and alternative diagnostics for tuberculosis in Tanzania: an integrated modelling approach. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e581–91.

Lin HH, Langley I, Mwenda R, Doulla B, Egwaga S, Millington KA, Mann GH, Murray M, Squire SB, Cohen T. A modelling framework to support the selection and implementation of new tuberculosis diagnostic tools. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:996–1004.

Bradley SP, Hax AC, Magnanti TL. Applied mathematical programming. Boston: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1977.

Cleary S, Mooney G, McIntyre D. Equity and efficiency in HIV-treatment in South Africa: the contribution of mathematical programming to priority setting. Health Econ. 2010;19:1166–80.

Epstein D, Chalabi Z, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Efficiency, equity and budgetary policies: informing decisions using mathematical programming. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:128–37.

Hontelez JAC, Change AY, Ogbuoji O, de Vlas SJ, Barnighausen T, Atun R. Changing HIV treatment eligibility under health system constraints in sub-Saharan Africa: investment needs, population health gains, and cost-effectiveness. AIDS. 2016;30:2341–50.

van Baal P, Thongkong N, Severens JL. Human resource constraints and the methods of economic evaluation of health care technologies. In: iDSI Methods Working Group report; 2016.

Churchyard GJ, Mametja LD, Mvusi L, Ndjeka N, Hesseling AC, Reid A, Babatunde S, Pillay Y. Tuberculosis control in South Africa: successes, challenges and recommendations. S Afr Med J. 2014;104:244–8.

Claassens MM, Jacobs E, Cyster E, Jennings K, James A, Dunbar R, Enarson DA, Borgdorff MW, Beyers N. Tuberculosis cases missed in primary health care facilities: should we redefine case finding? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:608–14.

White RG, Charalambous S, Cardenas V, Hippner P, Sumner T, Bozzani F, Mudzengi D, Houben RMGJ, Collier D, Kimerling ME, et al. Evidence-informed policymaking at country level: lessons learned from the South African Tuberculosis Think Tank. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22:606–13.

National Department of Health, South Africa National AIDS Council. South African HIV and TB investment case. Reference report. Phase 1; 2016.

Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.FCRF. Accessed 28 April 2017.

Remme M, Siapka M, Sterck O, Ncube M, Watts C, Vassall A. Financing the HIV response in sub-Saharan Africa from domestic sources: moving beyond a normative approach. Soc Sci Med. 2016;169:66–7.

South African Nursing Council Statistics. http://www.sanc.co.za/stats_ts.htm. Accessed 26 Oct 2017.

United Nations Population Division. United Nations population projections, 2015 revision. New York: United Nations Population Division; 2015.

WHO. WHO Global TB report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

IHME. Global burden of disease study. Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2013.

Churchyard GJ, Stevens WS, Mametja LD, McCarthy KM, Chihota V, Nicol MP, Erasmus LK, Ndjeka NO, Mvusi L, Vassall A, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF versus sputum microscopy as the initial diagnostic test for tuberculosis: a cluster-randomised trial embedded in South African roll-out of Xpert MTB/RIF. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e450–7.

Sumner T, Bozzani F, Mudzengi D, Hippner P, Cardenas V, Vassall A, White R. Incorporating resource constraints into mathematical models of TB: an example of case finding in South Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 (Under review).

WHO. Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: principles and recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Registered Nurse Salary (South Africa). https://www.payscale.com/research/ZA/Job=Registered_Nurse_(RN)/Salary. Accessed 27 Oct 2017.

Regulations Index—Educations and Training. http://www.sanc.co.za/regulat/index.html#EandT. Accessed 26 Oct 2017.

Reid S. Monitoring the effect of the new rural allowance for health professionals. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2004.

South Africa National AIDS Council. South Africa’s National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2017–2022. Pretoria: South Africa National AIDS Council; 2017.

Authors’ contributions

FB analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. GBG and DM assisted with the cost and human resource data collection and with the fiscal space analysis. TS and PH coded and carried out the epidemiological modelling supporting this analysis. SC and VC participated in the TB Think Tank and assisted with the identification and characterisation of health system constraints. AV and RW conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out with support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (SA Modelling for Policy: OPP1110334). The authors would like to thank the National Department of Health and the National TB Programme in South Africa, in particular Dr. Yogan Pillay, Dr. David Mametja, Dr. Lindiwe Mvusi and Dr. Norbert Ndjeka for their time and advice. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Gavin Churchyard at the Aurum Institute in Johannesburg, who led this project in South Africa and collaborated on the research. RGW is funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement that is also part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union (MR/P002404/1), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (TB Modelling and Analysis Consortium: OPP1084276/OPP1135288, CORTIS: OPP1137034, Vaccines: OPP1160830) and UNITAID (4214-LSHTM-Sept15; PO 8477-0-600).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the present article and its Additional file 1, as well as in the complementary publication by Sumner et al. [27] referred to in this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was received by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 11226) and by the Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand (Ref. 160611).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1.

Technical appendix.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bozzani, F.M., Mudzengi, D., Sumner, T. et al. Empirical estimation of resource constraints for use in model-based economic evaluation: an example of TB services in South Africa. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 16, 27 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-018-0113-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-018-0113-z