Abstract

Background

Generally, public health policy-making is hardly a linear process and is characterized by interactions among politicians, institutions, researchers, technocrats and practitioners from diverse fields, as well as brokers, interest groups, financiers and a gamut of other actors. Meanwhile, most public health policies and systems in Africa appear to be built loosely on technical and scientific evidence, but with high political systems and ideologies. While studies on national health policies in Africa are growing, there seems to be inadequate evidence mapping on common themes and concepts across existing literature.

Purpose

The study seeks to explore the extent and type of evidence that exist on the conflict between politics and scientific evidence in the national health policy-making processes in Africa.

Methods

A thorough literature search was done in PubMed, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, Dimensions, Taylor and Francis, Chicago Journals, Emerald Insight, JSTOR and Google Scholar. In total, 43 peer-reviewed articles were eligible and used for this review.

Result

We found that the conflicts to evidence usage in policy-making include competing interests and lack of commitment; global policy goals, interest/influence, power imbalance and funding, morals; and evidence-based approaches, self-sufficiency, collaboration among actors, policy priorities and existing structures. Barriers to the health policy process include fragmentation among actors, poor advocacy, lack of clarity on the agenda, inadequate evidence, inadequate consultation and corruption. The impact of the politics–evidence conflict includes policy agenda abrogation, suboptimal policy development success and policy implementation inadequacies.

Conclusions

We report that political interests in most cases influence policy-makers and other stakeholders to prioritize financial gains over the use of research evidence to policy goals and targets. This situation has the tendency for inadequate health policies with poor implementation gaps. Addressing these issues requires incorporating relevant evidence into health policies, making strong leadership, effective governance and a commitment to public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The state of human health varies globally, such that long-term human security is endangered at multiple levels [1, 2]. Current and future efforts aimed at containing and improving population health and well-being are expressed in many national health policies [3]. A national health policy is a planned course of action carried out by a country or state to attain defined healthcare goals [4,5,6]. Perhaps, public policy-making and its processes are at the instance of the political leaders [1]. Generally, public policy-making is hardly a linear process, characterized by interactions between and among politicians, institutions, researchers, technocrats and practitioners from varied fields, as well as brokers, interest groups and a gamut of other actors [5]. Right from its inception through to review, the policy-making process can be burdened with serious rifts, especially among the principal actors such as politicians, researchers and technocrats [7] which could place limitations on the use of evidence to inform the policy.

There are several frameworks for policy analysis, but the health policy triangle (HPT) by Walt and Gilson [8, 9] gained popularity. The HPT consists of four main constructs, including the policy context, policy content, policy process and the policy actors. The policy context refers to the socioeconomic, political, cultural and other environmental variables that necessitate the policy [8, 9]. The policy content refers to the core policy objectives, regulations and legislations that underpinned the policy. The policy process refers to how the policy evolves, from conception, formulation, negotiation, communication and implementation to evaluation. Moreover, policy actors refer to significant individuals, groups and institutions that influence the policy process [8, 9]. Thus, critically following the tenets of this framework may lead to formulation and implementation of health promoting policies that help lesson the burden of ill health on Africa. Meanwhile, a robust and evidence-based health policy is most likely to guarantee equitable and optimum human health [10].

Furthermore, it is believed that health policies in Africa are driven largely by political rather than technical interests backed by robust evidence [3]. However, factors such as funding, scientific evidence, interest and activities of lobbyists, and political interest/commitment influence national health policies [3, 11]. The policy-making process, either driven by need, evidence based or political interest, determines the core policy objectives and how they are attained. Thus, poorly crafted and implemented health policies in Africa, for instance, challenge access to quality health because of poor funding, corruption, equity and quality gaps, making such policies ill-prepared for national emergencies [1, 7, 10]. Meanwhile, universal health coverage by WHO, re-echoed in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), remains a dream for the majority of countries in Africa [1, 12]. Therefore, this conflict between the use of political goals and objectives over research evidence in public health policy-making needs exploration.

Several studies have revealed that public health policies and systems appear to be built loosely on technical and scientific evidence, but with high political systems and ideologies [13,14,15,16]. For instance, in most African countries such as Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tunisia, and Zimbabwe, the management of the novel SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the public health response have been heavily politicized [16,17,18]. Regardless of the seeming increase in research evidence on the central role of political leadership in defining national public health policies in Africa, there seems to be inadequate empirical accounts of the common themes or concepts in the existing literature regarding the politics–evidence conflict in the public health policy-making process [18, 19]. For instance, though evidence exists of the advances in knowledge about evidence-led health policies [19], research on the politics–evidence relationship remains largely unclear. Furthermore, while studies on health systems strengthening gave prominence to the role of technical knowledge in public health policy effectiveness, evidence on how politics shapes health systems is unclear [20, 21]. However, such health development in Africa is largely driven by politics [16,17,18]. Clearly, there is the need to establish the common themes and concepts that cut across the existing literature on the subject under discussion. Therefore, to fill this research gap, this review scoping explores the extent of evidence in relation to politics and scientific evidence utilization in the national health policy-making process in Africa.

Materials and methods

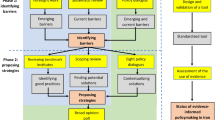

We utilized only peer-reviewed articles to examine the relationship between politics and scientific evidence in the national health policy-making processes in Africa. We utilized the approach of Tricco et al. [22] in probing, synthesizing and analysing appropriate peer-reviewed articles. The approach includes (i) outlining and developing the purpose of the review, (ii) outlining and critically examining the review questions, (iii) identifying and scrutinizing article search terms, (iv) identifying and exploring related databases and downloading useful articles, (v) screening the data, (vi) summarizing the data and reconciling the results, and (vii) consulting [22]. Therefore, two research questions informed the review: (1) what is the nature of politics–evidence conflict in national health policy-making in Africa? and (2) what are the challenges with politics–evidence conflict in national health policy-making in Africa?

This paper was also guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension (PRISMA) [22, 23]. We sourced peer-reviewed records from the following databases/search engines/publishers: PubMed, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, Dimensions, Taylor and Francis, Chicago Journals, Emerald Insight, JSTOR and Google Scholar (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). To guarantee rigidity and comprehension in the search procedure, medical subject heading (MeSH) terminologies were used. The search was conducted at two levels: level one applied the terms “Health policy*” OR “Health politics*” OR “Policymaking*” OR “Policy-making*”, which produced 186 articles. At the second level, additional MeSH terms were introduced: “Africa” OR “Developing countries” OR “Health Care reforms/organisation & administration” OR “Health care sector/standards” OR “Leadership” OR “Evidence-Based Medicine” OR “Public Health” OR “Public policy” OR “Sub-Saharan Africa” OR “Health promotion/trends”, across the databases/search engines/publishers which also yielded 523 articles (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). The scope of the search spanned articles published between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2023, with searches carried out between 1 November 2022 and 31 January 2024.

Following the initial search, duplicate articles were imported into and merged in the Mendeley. To attain rigour in the screening, four authors (2, 3, 4 and 5) did the initial screening of titles and abstracts. Subsequently, all articles that passed the inclusion criteria (defined below) were thoroughly reviewed. Doubts over the qualification of an article were resolved by two authors (1 and 6) through detailed discussion until a consensus was reached. With the PRISMA protocol, citation chaining was conducted on all papers that qualified, to identify additional useful articles for further assessment. The first author led, supervised and substantially helped to resolve all discrepancies during data extraction and quality assessment processes.

Inclusion criteria

Studies about Africa that explored evidence–politics conflict in national health policy-making processes and written in the English language only were included for studies done between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2023. Additionally, articles must have given details on the author(s), purpose/aim, methods/setting, nature of politics–evidence conflict, type of health policy, impact of politics–evidence conflict and conclusion/recommendations.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded articles that were not peer reviewed and those with substantial limitations or poor quality. Also, commentaries, grey literature, opinion pieces and media reports were excluded from this review. Articles on politics–evidence conflict that were not conducted in Africa were excluded.

Quality rating and assessment

Using the procedure of Tricco et al. [22], articles that met the inclusion criteria went through quality rating. Articles that provided background, aims/objectives, context, appropriateness of design, sampling, data collection and analysis, reflectivity, the value of research and ethics were accepted. Thus, the articles were judged and total scores assigned based on the majority of the sections. Articles that scored “A” had few or no limitations, “B” had some limitations, “C” had significant limitations but possessed some relevance and “D” contained substantial flaws that could undermine the findings of the study. Therefore, articles that scored “D” were excluded from the review.

Data extraction and thematic analysis

Five authors (2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) independently extracted the data. Three authors (2, 3 and 4) extracted data on the author(s), purpose/aim, methods/setting, nature of politics–evidence conflict and type of health policy. Meanwhile, two authors (5 and 6) extracted data on the impact of politics–evidence conflict and conclusions/recommendations (see Table 2). Data extraction was done under the supervision of authors 1 and 6. Using the method of Braun and Clarke [23], a thematic analysis was conducted by three authors (1, 4 and 6). Therefore, data were coded and the themes emerged inductively and yet guided by the stated research questions. The data analysis commenced with multiple readings of the text to familiarize with the data, we then created initial codes, critically assessed the themes, revised the themes, defined and labelled the themes, and produced the report. Additionally, the emerged themes went through exhaustive discussion by all authors to reach a consensus. The themes further went through repeated reviews based on new data until the final themes emerged.

Findings

The study explored the extent and type of evidence that exists on the conflict between politics and scientific evidence in the national health policy-making processes in Africa. We included 43 papers published between 2013 and 2023. Out of the total, 11(25.6%) [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] originated from Western Africa only, 11(25.6%) [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] from Southern Africa only, 11(25.6%) [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] from Eastern Africa only and 3(7.1%) [57,58,59] from Eastern and Southern Africa. Also, 1(2.3%) [60] from Northern only, 1(2.3%) [61] from Central only, 1(2.3%) [62] from Eastern and Western, 1(2.3%) [63] from Western and Northern, 1(2.3%) [64] from Western and Southern, 1(2.3%) [65] from Central, Eastern, Western and Southern, and 1(2.3%) [66], thus, cutting across the entire continent. The approaches adopted by these articles included quantitative 2(4.5%) [39, 66], qualitative 39(91%) [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 35,36,37,38, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51, 53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] and mixed method 2(4.5%) [33, 52]. The findings are presented by the nature of the conflict, drivers, barriers and impacts of politics–evidence conflicts on national health policy-making in Africa.

Nature of politics–evidence conflict in national health policy-making in Africa

Our review revealed some form of competing interest in national policy dialogue, from formulation to implementation phases. The most commonly reported conflicting issues include confusion about policy priorities with political ideologies, donor interests and influences [24,25,26,27,28,29,30, 51]. We also found that moral, legal restrictions and government priorities are key competing interests in most African countries concerning national health policy-making. Wanjohi et al. [28] noted that governments have competing roles, for example, the sugar-sweetened taxation policy in Kenya.

We found a persistent poor government commitment in most public health policy initiations, formulations and implementations [24, 26, 29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Again, most public policies were formulated and implemented based on the motivation of policy-makers’ financial incentives as well as government and foreign policy conditionalities [27, 30, 36, 37, 39].

It emerged also that donor financing facilitated the process of national public health policy, but strategically skewed the power balance and goals of some health policies [24, 40, 41]. In some cases, donor powers were used in the positive direction, but negatively in others [29, 41,42,43,44]. Moreover, power imbalances associated with funding sometimes disrupt the flow of funds from donors, something which negatively affects the content and original purpose of national public health policies in Africa [41, 42, 45].

Drivers of public health policy-making in Africa

We found that political commitment and strong collaboration among actors, stakeholders and development partners drive public health policy formulation [29, 33, 34, 36,37,38, 44, 46, 62]. Also, strong existing policies and legal frameworks, employing evidence-based approaches in the policy formulation process, self-sufficiency, prioritization of basic needs and acknowledging weaknesses in the national system and taking measures to resolve such improve policy dialogue [29, 34, 44].

It also emerged that strong government leadership and empirical-based approaches, effective engagement of experienced stakeholders, policy alignment with political priorities and evidence-based interventions are effective in policy formulation [46]. Furthermore, social, political, economic and institutional factors influence the effectiveness of national policy processes [35, 39, 47, 49, 50]. Additionally, the integration of national policies into international ones and formulation of new policies were driven by stakeholder interests, advocacy and collaborative efforts from civil society and the global advocacy movements [34, 47, 66].

Barriers to national public health policy-making in Africa

We found that fragmented stakeholder interest, institutional responsibility and accountability, inadequate understanding and interpretation of context by stakeholders divided perspectives of actors on the policy context, and lack of understanding among actors about how policy should be financed limits national public health policy formulation [27, 30, 41, 51,52,53]. Moreover, incomplete and inaccurate data, poor management of resources, improper coordination and communication between actors, inadequate consultation with relevant stakeholders and inconsistency among actors during policy dialogue and formulation processes are also critical limitations to policy formulation [26, 40, 41, 52,53,54,55].

Furthermore, it emerged that a lack of strategic leadership and a clear action plan regarding policy processes, poor characteristics of political players and difficulty in understanding and interpreting context by stakeholders frustrate policy processes [25, 28, 32, 35, 37, 53, 54, 59]. Additionally, lack of decentralization of policy formulation and implementation, poor resource mobilization and lack of political engagement with policy beneficiaries, implementers and other relevant stakeholders suffocate some policies in the continent [38, 51, 53, 56]. Besides, most national public health policy processes were motivated by policy-makers’ financial incentives as well as government and foreign policy conditionalities in Africa [27, 36, 40, 46, 57].

Impacts of politics–evidence conflict in public health policy-making

There are delays in policy dialogue and implementation due to disparities between policy expectations and actual practice, weak policy processes that do not take into account the relevant actors and lapses in policy context [24, 42, 48, 51, 55]. We also noticed delays in the policy formulation process due to high political and external conflict [25, 28, 30, 37, 53]. Moreover, due to poor engagement with policy players, fragmented governance and weak monitoring systems, some health policies do not meet their intended purposes [33, 37, 38, 41, 43,44,45, 54, 57,58,59].

Fortunately, evidence suggests a consensus among actors in the policy process which promotes collective ownership, high political commitment, pressure from civil society and other relevant stakeholders as well as policy alignment with political priorities that led to some successes in public health policy formulation [29, 31,32,33,34, 46, 51, 60].

Discussion

Strong empirical evidence is the backbone for impactful national health policy. Pursuant to this, we explored the extent of evidence of conflict of politics and scientific evidence in the national health policy-making process in Africa. The study revealed four significant themes under which the discussion is organized. These include political influence in public health policy, drivers of public health policy, barriers to effective public health policy and impact of politics–evidence conflict on public health policy-making process in Africa.

Political influences in public health policy

We report that public health policies in Africa are heavily influenced by politics rather than scientific evidence. Most governments succumbed to donor interest which largely define the policy process [28, 30, 37]. This is consistent with several previous studies [1, 13, 19, 20] who reported similar findings. Meanwhile, the interests of these donors are often at variance with the health needs of the citizenry in Africa. Moreover, affirming previous studies [13, 19], our current study exposed the influence willed by donors which reiterates the power imbalance and lack of independence that sometimes characterizes policy-making in Africa to the detriment of its local needs.

In contrast to the findings of the current study, an earlier study [20] recognized the role of political ideology in the national health policy process. Meanwhile, the reviewed articles [24, 45, 47, 48, 57] showed that political influence undermines policy formulation that cater for sustainable health development in the continent. For instance, Oleribe and colleagues [67] attributed the failure of abortion policies in Burkina Faso and other sub-Saharan African countries to political influence and poor stakeholder consultation. This could be largely due to limited financial capacities and impositions by global organizations and allegiances.

Drivers of public health policy

We found that, generally, the main drivers of public health policies in Africa include health organizations, donor agencies, development partners, political manifestos and nongovernmental agencies [34, 35, 38]. For instance, a review of the National Health Insurance Policy of Ghana revealed that its success stemmed from its alignment with the political manifestos of successive governments [36]. This agrees with previous studies [2, 3] which revealed how donor agencies, development partners and political manifestos drove public policies. Furthermore, global agencies such as WHO, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and others collaborate very much to drive the health policy directions, especially the less developed nations, in meeting global health standards such as the SDGs for health. Thus, strong advocacy and partnership influence policy direction in all affiliate countries.

Barriers to effective public health policy

The main barriers affecting an effective public health policy-making process in Africa include poor consultation, orientation and decentralization [26, 29, 36]. Typically, political policies are expected to promote stakeholder consultation, orientation and proper decentralization of health interventions. However, we found that political policies and activities are rather undermining stakeholder consultation, orientation and proper decentralization of health interventions [26, 29, 36]. This strongly upholds findings from previous studies [3, 5, 15, 16] that political interests undermined successful implementation of national policies. This is mostly because governments in Africa lacked adequate resources and empirical evidence to effectively drive health policy process to a successful implementation [30, 41, 45, 47]. Unfortunately, disparities in expectations and systems account for lapses in the policy context and the entire formulation process [28, 32, 44, 53, 61, 62]. Some previous studies [5, 16] have reported how implementation of public policies fell short of public expectations. Moreover, leadership corruption, inadequate consultation, poor advocacy and inadequate use of core evidence in policy-making and implementation compromise the future of public health in Africa.

Impacts of politics–evidence conflict on public health policy

We found that competing interests, political dishonesty and lack of political commitment affect the expected health needs of many African populations [24, 26, 51]. Poor coordination of key policy actors such as donors and other stakeholders, coupled with poor integration of global goals into local health policy frameworks undermined intersector participation which results in poor health policy formulation and implementation [24, 26, 51]. According to previous studies [15, 68], health policies of most developing countries are driven by political propaganda that often does not deal with the critical health needs of the citizenry. Meanwhile, the evidence is that in a few countries where health policies are led by empirical evidence and supported by political commitment, health indicators improved [63, 64]. For instance, we found that in Kenya, Ethiopia and South Africa, effective participation of healthcare professionals and other key stakeholders in developing policies on abortion lead to significant reductions in mortality due to illegal abortions [63, 64]. Then, effective stakeholder participation becomes key to the success of public policy implementation [15]. Therefore, effective decentralization and stakeholder participation, specifically the targeted beneficiaries and healthcare professionals, are necessary to engender effective policy implementation.

Alignment of findings with policy frameworks

The current review aligns well with Walt and Gilson’s policy framework. First, we found that donor interests, mostly championed by political interests (policy context), largely define most national health policies in Africa [28, 30, 37]. Second, rather than evidence-based policy objectives and legislations, the contents of most national health policies in Africa do not align well with the needs of the locals (policy content). This creates misalignment in policy in objectives and content to the detriment of the health of the African citizen. Thus, the content of most national health policies failed to address the critical health needs of the ordinary African citizen. Third, such policies are driven by donor interests that are supported by political interest (policy process) into key policy activities from policy conception, formulation, negotiation and communication to evaluation [24, 26, 51]. Fourth, on the policy actors, key stakeholders such as health professionals, academia and community leaders do not actively participate in the policy process in Africa. This ultimately undermines policy ownership and implementation success [5, 16].

Strengths and limitations

This study is a significant addition to existing empirical accounts of the politics–scientific evidence conflict in the national health policy-making process in Africa. To uphold compression and rigour in the search procedure, we applied the MeSH terms in search of only peer-reviewed articles on the variables. Additionally, we set inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the reviewed articles went through a rigour of quality rating, using standardized guidelines. Moreover, data extraction was independently conducted and verified by all authors. These notwithstanding, there are limitations worth acknowledging. First, including only peer-reviewed articles that are written in the English language and covering only Africa may have limited the literature samples used in this study. Thus, some excluded articles, written in other languages, may contain important details. Moreover, we acknowledge that the inherent weaknesses and biases in the reviewed articles are carried into our research.

Recommendations for policy direction and research

Based on the findings from this review, we reiterate evidence-based agenda setting before any policy process. More importantly, policy-makers should research and establish strong evidence to demonstrate the viability of the proposed policy. Additionally, government and political leadership may want to limit corruption and be committed to ensuring that the policy agenda meets the immediate local needs and that global policy initiatives do not undermine pressing domestic health needs. Furthermore, it is recommended that all stakeholders, including implementers and beneficiaries, are engaged and fully participate in the entire policy process. Finally, we recommend that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the policy agenda and what is expected to achieve, and remain resolute to the collective purpose through the policy processes.

Conclusions

The extent of political–evidence conflict in national health policy processes is marked by obstructions. There are issues related to corruption, where political interests prioritize their financial gain over the needs of the healthcare system and the public. The potential impact on health in Africa is an increase in disease burden, lack of productivity and lack of progressive health development. There is largely inadequate funding for healthcare, a situation that is resulting in poor public health policy implementation leading to inadequate availability of essential medicines and supplies, and causing other negative impacts on public health.

Addressing these conflicts between political interests and evidence into health policy formulation and implementation require strong leadership, effective governance and commitment to the public health agenda. It also requires collaboration between and among different stakeholders, including government officials, healthcare providers, researchers and civil society organizations. By working together, it is possible to develop policies and strategies that are evidence based, equitable and sustainable, that promote the health and well-being of all persons in Africa.

Availability of data materials

All relevant data provided in the appendix.

Abbreviations

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject headings

- PRAs:

-

Peer-reviewed articles

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- UNDP:

-

United Nations Development Programme

References

Benatar S, Sullivan T, Brown A. Why equity in health and in access to health care are elusive: insights from Canada and South Africa. Glob Public Health. 2018;13(11):1533–57.

Benatar SR. Explaining and responding to the Ebola epidemic. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13010-015-0027-8.

AbuAlRub RF, Abdulnabi A. Involvement in health policy and political efficacy among hospital nurses in Jordan: a descriptive survey. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28:433–40.

World Health Organization: Health policy. 2017. http://www.who.int/topics/health_policy/en/. Accessed 13 Dec 2022.

Cullerton K, Donnet T, Lee A, Gallegos D. Using political science to progress public health nutrition: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2015;19(11):2070–8.

Abualrub R, Foudeh F. Jordanian Nurses involvement in health policy: perceived benefits and barriers. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(1):13–20.

Whitty CJM. What makes an academic paper useful for health policy? BMC Med. 2015;13:301.

Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, Murray SF, Brugha R, Gilson L. ‘Doing’ health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23:308–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czn024.

O’Brien GL, Sinnott S-J, Walshe V, Mulcahy M, Byrne S. Health policy triangle framework: narrative review of the recent literature. Health Policy. 2020;1: 100016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpopen.2020.100016.

van de Goora I, Hämäläinenb R, Syedc A, Laud CJ, Sandue P, Spittersa H, et al. Determinants of evidence use in public health policy making: results from a study across six EU countries. Health Policy. 2017;121:273–81.

Østebø MT, Cogburn MD, Mandani AS. The silencing of political context in health research in Ethiopia: why it should be a concern. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(2):258–70.

Reis AA. Universal health coverage – the critical importance of global solidarity and good governance: comment on “ethical perspective: five unacceptable trade-offs on the path to universal health coverage. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2016.61.

Gore R, Parker R. Analysing power and politics in health policies and systems. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(4):481–8.

Bremmer I: The best global responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 Year Later. 2019. https://time.com/5851633/best-globalresponses-covid-19/. Accessed 28 Jun 2021.

Lavers T. Aiming for Universal Health Coverage through insurance in Ethiopia state infrastructural power and the challenge of enrolment. Soc Sci Med. 2021;282:114–74.

Østebø MT, Østebø T, Tronvoll K. Health and politics in pandemic times: COVID-19 responses in Ethiopia. Health Policy Plan. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czab091.

Lavers T. Towards Universal Health coverage in Ethiopia’s ‘developmental state’? The political drivers of health insurance. Soc Sci Med. 2019;228:60–7.

Jasanoff S, Stephen Hilgartner J, Hurlbut B, Özg¨ode O, Rayzberg M. Comparative covid response: Crisis, knowledge, politics. 2021. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/comparative-covid-response-crisis-knowledge-politics. Accessed 13 Oct 2022.

Bossert TJ, Parker DA. The political and administrative context of primary health care in the third world. Soc Sci Med. 1984;18(8):693–702.

Gilson L, Raphaely N. The terrain of health policy analysis in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature 1994–2007. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):294–307.

Storeng KT, Mishra A. Politics and practices of global health: critical ethnographies of health systems. Glob Public Health. 2014;9(8):858–64.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Agyepong IA, Cormack-hale FAOM, Amoakoh HB, Derkyi-kwarteng ANC, Darkwa TE, Odiko-ollennu W. Synergies and fragmentation in country level policy and program agenda setting, formulation and implementation for Global Health agendas : a case study of health security, universal health coverage, and health promotion in Ghana and Sierra Leone. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(476):1–15.

Dalglish SL, Rodríguez DC, Harouna A, Surkan PJ. Knowledge and power in policy-making for child survival in Niger. Soc Sci Med. 2017;1(177):150–7.

Etiaba E, Eboreime EA, Dalglish SL, Lehmann U. Aspirations and realities of intergovernmental collaboration in national- level interventions: insights from maternal, neonatal and child health policy processes in Nigeria, 2009–2019. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(2): e010186.

Abubakar I, Dalglish SL, Ihekweazu CA, Bolu O, Aliyu SA. Lessons from co-production of evidence and policy in Nigeria’s COVID-19 response. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(3): e004793.

Koduah A, Agyepong IA, Dijk HV. Towards an explanatory framework for national level maternal health policy agenda item evolution in Ghana: an embedded case study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(76):1–16.

Novignon J, Lanko C, Arthur E. Political economy and the pursuit of universal health coverage in Ghana: a case study of the National Health Insurance Scheme. Health Policyand Plan. 2021;36:14–21.

Okedo-Alex IN, Res H, Sys P, Nkem I, Alex O, Akamike IC, et al. Identifying advocacy strategies, challenges and opportunities for increasing domestic health policy and health systems research funding in Nigeria: perspectives of researchers and policymakers. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19:1–11.

Ridde V, Faye A. Policy response to COVID-19 in Senegal: power, politics, and the choice of policy instruments. Policy Des Pract. 2022;5(3):326–45.

Seddoh A, Akor SA. Policy initiation and political levers in health policy: lessons from Ghana ’ s health insurance. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(Suppl 1):S10.

Simen-Kapeu A, Lewycka S, Ibe O, Yeakpalah A, Horace JM, Ehounou G, et al. Strengthening the community health program in Liberia: lessons learned from a health system approach to inform program design and better prepare for future shocks. J Glob Health. 2021;30(11):07002.

Thow AM, Apprey C, Winters J, Stellmach D, Alders R. Understanding the impact of historical policy legacies on nutrition policy space: economic policy agendas and current food policy paradigms in Ghana. Int J Policy Manag. 2021;10(12):909–22.

Amukugo HJ, Karim SA, Thow AM, Erzse A, Kruger P, Karera A, et al. Barriers to, and facilitators of, the adoption of a sugar sweetened beverage tax to prevent non- communicable diseases in Namibia: a policy landscape analysis. Glob Health Action. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1903213.

Colvin CJ, Kallon II, Swartz A, Macgregor H, Kielmann K, Grant AD, et al. ‘It has become everybody ’s business and nobody’s business ’: policy actor perspectives on the implementation of TB infection prevention and control (IPC) policies in South African public sector primary care health facilities. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(10):1631–44.

Ditlopo P, Blaauw D, Penn-kekana L, Rispel LC, Ditlopo P, Blaauw D, et al. Contestations and complexities of nurses’ participation in policy-making in South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):25327.

Ditlopo P, Blaauw D, Rispel L, Thomas S, Thomas S, Bidwell P. Policy implementation and financial incentives for nurses in South Africa: a case study on the occupation-specific dispensation Prudence. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1):19289.

Gavriilidis G, Östergren PO. Evaluating a traditional medicine policy in South Africa: phase 1 development of a policy assessment tool. Glob Health Action. 2012;5(1):1–11.

Haaland MES, Haukanes H, Mumba J, Marie K, Blystad A. Social Science & Medicine Silent politics and unknown numbers: rural health bureaucrats and Zambian abortion policy. Soc Sci Med. 2020;251(March): 112909.

Jacobs T, George A. Original article between rhetoric and reality : learnings from youth participation in the adolescent and youth health policy in South Africa. Int J Policy Manag. 2022;11(12):1–13.

Kielmann K, Dickson-hall L, Jassat W, Roux SL, Moshabela M, Cox H, et al. ‘We had to manage what we had on hand, in whatever way we could ’: adaptive responses in policy for decentralized drug-resistant tuberculosis care in South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36:249–59.

Masefield SC, Msosa A, Chinguwo FK, Grugel J. Stakeholder engagement in the health policy process in a low-income country: a qualitative study of stakeholder perceptions of the challenges to effective inclusion in Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):984.

Modisenyane SM, James S, Hendricks H, Modisenyane SM. Understanding how domestic health policy is integrated into foreign policy in South Africa : a case for accelerating access to antiretroviral medicines South Africa: a case for accelerating access to antiretroviral medicines. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1339533. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1339533.

Zulu JM, Chavula MP, Silumbwe A, Munakampe MN. Exploring politics and contestation in the policy process: the case of Zambia’s contested community health strategy. Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2022;11(1):24–30.

Croke K. The origins of Ethiopia’s primary health care expansion: the politics of state-building and health system strengthening. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35:1318–27.

Holcombe SJ, Gebru SK. Agenda setting and socially contentious policies: Ethiopia’s 2005 reform of its law on abortion. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):1–18.

Hussein S, Otiso L, Kimani M, Olago A, Wanyungu J, Kavoo D, et al. Institutionalizing community health services in Kenya: a policy and practice journey. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021;9(S1):25–31.

Kagaha A, Manderson L. Power, policy and abortion care in Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36:187–95.

Koon AD, Hawkins B, Mayhew SH. Framing universal health coverage in Kenya: an interpretive analysis of the 2004 Bill on National Social Health Insurance. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35:1376–84.

Mac-Seing M, Ochola E, Ogwang M, Zinszer K, Zarowsky C. Policy implementation challenges and barriers to access sexual and reproductive health services faced by people with disabilities: an intersectional analysis of policy actors’ perspectives in post-conflict Northern Uganda. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(7):1187–96.

Mauti J, Gautier L, Agbozo F, Shiroya V, Jessani NS, Tosun J, et al. Original article addressing policy coherence between health in all policies approach and the sustainable development goals implementation: insights from Kenya. Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2022;11(6):757–67.

Mukuru M, Kiwanuka N, Gilson L, Shung-king M, Ssengooba F. “The Actor Is Policy”: application of elite theory to explore actors’ interests and power underlying maternal health policies in Uganda, 2000–2015. Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2021;10(7):388–401.

Oraro-Lawrence T, Wyss K. Policy levers and priority-setting in universal health coverage: a qualitative analysis of healthcare financing agenda setting in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–11.

Shiroya V, Neuhann F, Müller O, Deckert A, Shiroya V, Neuhann F. Challenges in policy reforms for non- communicable diseases: the case of diabetes in Kenya Challenges in policy reforms for non-communicable diseases: the case of diabetes in Kenya. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(1):1611243. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2019.1611243.

Wanjohi MN, Thow AM, Karim SA, Asiki G, Erzse A, Mohamed SF, et al. Nutrition-related non-communicable disease and sugar-sweetened beverage policies: a landscape analysis in Kenya. Glob Health Action. 2021;14(1):1902659. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1902659.

Blystad A, Haukanes H, Tadele G, Haaland MES, Sambaiga R, Zulu JM, et al. The access paradox: abortion law, policy and practice in Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Zambia. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(126):1–15.

Kumwenda M, Skovdal M, Wringe A, Kalua T, Songo J, Hassan F, et al. Exploring the evolution of policies for universal antiretroviral therapy and their implementation across three sub-Saharan African countries: findings from the SHAPE study therapy and their implementation across three sub-Saharan. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(2):227–40.

Omar MA, Green AT, Bird PK, Mirzoev T, Flisher AJ, et al. Mental health policy process: a comparative study of Ghana, South Africa, Uganda and Zambia. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2010;4(1):1–10.

Akhnif EH, Hachri H, Belmadani A, Mataria A, Bigdeli M. Policy dialogue and participation: a new way of crafting a national health financing strategy in Morocco. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(114):1–12.

Ruhara CM, Karim SA, Erzse A, Thow M, Ntirampeba S, Hofman KJ, et al. Strengthening prevention of nutrition-related non-communicable diseases through sugar-sweetened beverages tax in Rwanda: a policy landscape analysis. Glob Health Action. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1883911.

Alhelou N, Kavattur PS, Rountree L, Winkler IT. “We like things tangible:” a critical analysis of menstrual hygiene and health policy-making in India, Kenya, Senegal and the United States. Glob Public Health. 2022;17(11):2690–703.

Mwisongo A, Nabyonga-orem J, Yao T, Dovlo D. The role of power in health policy dialogues: lessons from African countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1456-9.

Sambala EZ, Manderson L. Policy perspectives on post-pandemic influenza vaccination in Ghana and Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–13.

Parkhurst J, Ghilardi L, Snow RW, Lynch CA, Webster J. Competing interests, clashing ideas and institutionalizing influence: insights into the political economy of malaria control from seven African countries. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36:35–44.

Murray GR, Rutland J. Prioritizing public health? Factors affecting the issuance of stay-at-home orders in response to COVID-19 in Africa. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(1): e0000112.

Oleribe OO, Momoh J, Uzochukwu BS, Mbofana F, Adebiyi A, Barbera T, Williams R, Taylor-Robinson SD. Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems in Africa and potential solutions. Int J Gen Med. 2019;12:395–403. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S223882.

Benatar SR. Health in low-income countries. In J. D. Wright (Ed.) International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 2015b;2(10):633–639.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There was no funding for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EWA, SM, AE, JEYO, MNB and NNB conceived and designed the review protocols. Authors SM, AE, JEYO, MNB and NNB conducted data collection and acquisition. EWA, JEYO and MNB Carried out extensive data processing and management. EWA, AE, JEYO and SM developed the initial manuscript. All authors edited and considerably reviewed the manuscript, proofread for intellectual content and consented to its publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansah, E.W., Maneen, S., Ephraim, A. et al. Politics–evidence conflict in national health policy making in Africa: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Sys 22, 47 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-024-01129-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-024-01129-3