Abstract

Background

To evaluate the performance of the patient clinical complexity level (PCCL) mechanism, which is the patient-level complexity adjustment factor within the Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups (KDRG) patient classification system, in explaining the variation in resource consumption within age adjacent diagnosis-related groups (AADRGs).

Methods

We used the inpatient claims data from a public hospital in Korea from 1 January 2017 to 30 June 2019, with 18 846 claims and 138 AADRGs. The differences in the total average payment between the four PCCL levels for each AADRG was tested using ANOVA and Duncan’s post hoc test. The three patterns of differences with R-squared were as follows: the PCCL reflected the complexity well (valid); the average payment for PCCL 2, 3, and 4 was greater than PCCL 0 (partially valid); the PCCL did not reflect the complexity (not valid).

Results

There were 9 (6.52%), 26 (18.84%), and 103 (74.64%) ADRGs included in the valid, partially valid, and not valid categories, respectively. The average R-squared values were 32.18, 40.81, and 35.41%, respectively, with an average R-squared for all patterns of 36.21%.

Conclusions

Adjustment using the PCCL in the KDRG classification system exhibited low performance in explaining the variation in resource consumption within AADRGs. As the KDRG classification system is used for reimbursement under the new DRG-based prospective payment system (PPS) pilot project, with plans for expansion, there should be an overall review of the validity of the complexity and rationality of using the KDRG classification system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The importance of complexity adjustment in diagnosis-related groups

Many countries have been concerned about the performance of the diagnosis-related groups (DRG) system for payment accuracy. In the United States, for example, many studies have evaluated whether variables other than the diagnosis variable could be used for the DRG or the predictive performance of cost between various types of case-mix measurement systems [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Many other countries have adopted and applied other variables such as types of hospitalization/discharge or methodologies that can detect variations within patient groups, taking into account their healthcare context [8,9,10,11].

Healthcare system and payment method in Korea

In Korea, more than 90% of hospitals are privately owned [12], with a more complex patient case mix in private hospitals than public hospitals. The main method for payment is the fee-for-service model, with no separate payments between hospitals and doctors by the National Health Insurance System. The single public insurer (National Health Insurance Service, NHIS) pays 80% of the hospital charge for inpatient stay, and the patient pays the remainder.

There are two types of DRG payment systems for patient classification in Korea that originated from the same patient classification system [13, 14]: (1) the mandatory DRG-based prospective payment system (PPS) for seven diseases, and (2) the new DRG-based PPS for public hospitals. The mandatory DRG-based PPS, including payments for both hospitals and doctors, targets seven relatively simple surgical disease groups, and was first introduced to certain clinics and hospitals in July 2012. It was then extended to all medical institutions in July 2013. Under the pilot project, the new DRG-based PPS targeted public hospitals with physician procedures, expensive therapeutic materials, and some expensive drugs paid separately as fee-for-service payments in the system. Since 2018, the new DRG-based PPS has been extended to private hospitals through voluntary participation.

Overview of the complexity adjustment of the Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups

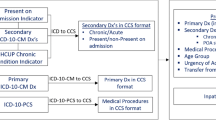

The mechanisms for reflecting the complexity of the Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups (KDRG) system (Additional file 1: The Structure of the Korean DRG classification and refinement step of ADRG based on secondary diagnosis), which was developed based on the United States Refined DRG (US R-DRG) and the Australian Refined DRG (AR-DRG), are as follows [15, 16]: (1) the patient's complications and comorbidities (CC) are assigned a severity score based on the CC list; (2) if there are multiple secondary diagnoses, the duplicates are removed by applying an exclusion list; and (3) the disease group severity is adjusted and refined using the patient clinical complexity level (PCCL) calculation formula that calculates the cumulative effects of the multiple diagnoses. The PCCL was designed to prevent similar diseases from being calculated more than once and is intended to reflect the cumulative effect of a patient’s CC [17, 18]. The PCCL value is calculated per patient episode, and the RDRG per age adjacent DRG (AADRG) is determined by considering the statistical criteria and the minimum number of counts [15, 16].

Follow-up study for previous research

This is a follow-up study of a previous study by Kim et al. [19] that reviewed the validity of the CC severity adjustment mechanism, which is a pre-PCCL calculation step in the KDRG classification system. In the previous study, the validity of the severity adjustment mechanism using CC was reviewed. Our previous study reported that only 114 (19.03%) out of 599 adjacent DRGs (ADRGs) had a valid comorbidities and complications level (CCL) [19]. However, we were not able to evaluate the accuracy of payment at the patient level. As the new DRG-based PPS is extended to private hospitals that have more complex patients than public hospitals in Korea, ensuring accurate payment at the patient level is important. Therefore, this follow-up study aims to validate the accuracy of payment at the patient level using the new DRG-based PPS in a public hospital.

Methods

Data

We used inpatient claims data from a general hospital with about 600 beds in Seoul, Korea (1 January 2017 to 30 June 2019). The hospital is a public hospital and one of the reference hospitals (three public and three private medical institutions) whose data have been used to set the base DRG fee for the new DRG-based PPS pilot project. A total of 26 784 claims were available in raw data.

The PCCL score and DRG code per episode were automatically assigned by the DRG grouper distributed by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA), which is responsible for the development of the KDRG classification system. Basic patient information, diagnoses, and procedures are the mandatory input data for the grouper. To evaluate the validity of the PCCL method, we used the PCCL scores and payment amount based on the fee for service, which is a proxy measurement for cost.

In KDRG, the ADRG is determined by a combination of primary diagnosis and main surgery or procedure that a patient undergoes, and is then classified by age as AADRG. Then, the AADRG is classified as RDRG, reflected by the severity of the secondary diagnoses. In the general DRG classification structure, ADRG is divided into RDRG, but the classification structure in the KDRG follows the order ADRG–AADRG–RDRG. In this paper, AADRGs can be understood as the same concept as the ADRG of the general DRG.

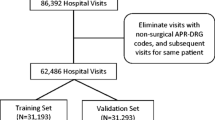

A total of 811 AADRGs in the KDRG v1.2 classification were used for the new DRG-based PPS, excluding early death DRG, error DRGs, and pre-major diagnostic category (MDC). Of the 26 784 claims in the general hospital claims database, there were 532 AADRGs (Fig. 1). Only 204 AADRGs in 20 609 claims contained PCCL scores of 0, 2, 3, or 4. We estimated the appropriate number of samples for each AADRG using G*Power 3.1 [20] and chose data on 138 AADRGs in 18 846 claims as analysis data.

The selection of study data for analysis. PCCL patient clinical complexity level, AADRG age adjacent DRG. †The PCCL scores consist of 0, 2, 3, and 4 levels. ‡The appropriate sample size for analysis of variance (ANOVA) was determined using G*Power according to AADRGs. The sample size means the number of data

Statistical analyses

The general characteristics of the data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as percentage for gender, age, type of insurance, length of stay, and payment amount. We also show data characteristics according to major diagnostic category (MDC) in the KDRG.

Only the AADRGs with adequate sample sizes were selected to report. We used G*Power 3.1 [20] to calculate the minimum sample sizes per AADRG. The alpha was set to 0.05, and the power to 0.8. Effect size was estimated from the SD within each group of each AADRG, the sample size, and mean of log-transformed payment amount from the actual data. For example, in AADRG I6821, where the number of groups = 4 and the SD within each group = 0.2656, the average log-transformed payment amounts were 6.32068, 6.45057, 6.7249, and 7.03847 for sample sizes of 97, 20, 7, and 3, respectively. The estimated effect size was 0.5360507, and the minimum sample size was 44. AADRG I6821 was selected to report because the actual sample size was 127.

The statistical hypothesis was that the average payment amount would increase significantly with an increase in the PCCL score. To evaluate the ability of the PCCL score to explain patient complexity, we performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s post hoc test using PCCL scores as an independent variable and the log-transformed payment amount as the dependent variable. The dependent variable is the sum of fees for medical services provided to patients under the fee-for-service payment system (Additional file 2: The diagram of analysis method).

The R2 value of the ANOVA is presented for the explanatory power of the PCCL on the payment amount.

Pattern analysis

Based on the same criteria as our previous research, we categorized the results of Duncan’s post hoc test by AADRGs into three different validity patterns: valid, partially valid, and not valid (Additional file 3: Criteria used to classify validity patterns).

The valid pattern included the AADRGs in which the average payment amount increased significantly with increase an in the PCCL score. B6623 in Additional file 4 is a good example. For the partially valid pattern, the average payment amount of PCCL 0 was significantly less than the lowest average payment amount of the other PCCLs. Duncan’s post hoc test for the payment amount of E7202 in Additional file 4 shows that the average payment amounts of PCCL 3 and PCCL 4 were not statistically different from that of PCCL 2, but different from that of PCCL 0. We considered them inappropriate but better than not valid. In the not valid pattern, the average payment amount of PCCL 0 is statistically equal to or greater than the average payment amount of other PCCLs. J6002 in Additional file 4 shows that the average payment amount of PCCL 0 is statistically the same as that of PCCL 2.

Results

General characteristics

The number of AADRGs and inpatient claims in the raw and analysis data at the MDC level is shown in Table 1. Of the 532 AADRGs, 138 (25.94%) AADRGs in 18 846 (70.36%) claims were included for analysis.

The validity pattern analysis

A summary of the pattern analysis of the validity of the PCCL scores is shown in Table 2. In nine AADRGs (6.52%), the average payment amount increased significantly with an increase in the four PCCL scores (0, 2, 3, 4), indicating a valid pattern. There were 26 AADRGs (18.84%) that were partially valid or had an average payment amount of PCCL 0 that was significantly less than the lowest average amount of other PCCL scores, and there were 103 AADRGs that were not valid (74.64%), meaning that they did not reflect the complexity between average payment and PCCL score, suggesting that the average amount of PCCL 0 was not significantly different from that of other PCCLs.

If we consider the valid and partially valid patterns as acceptable results in the current four PCCL scores reflecting the variation in average payment amount within AADRGs, the average payment amount of 103 AADRGs (74.64%) is not accounted for by the current four PCCL scores. On the other hand, if we consider only the valid pattern as an acceptable result, the average payment for 129 AADRGs (94.5%) is not accounted for by the four PCCL scores. The average R2 for the payment amount of AADRGs by the four PCCL scores in the valid, partially valid, and not valid patterns is 36.21%. The average R2 of the valid pattern between the average payment amount of AARDGs per PCCL score is 32.18%, which is lower than the average R2 of the partially valid or not valid patterns.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the mechanism of patient-level complexity adjustment in the KDRG. Our results showed that using PCCL for the new DRG-based PPS exhibited low performance. A study conducted in Australia reported a newly developed complexity adjustment mechanism, since the existing PCCL measure developed using limited data on length of stay had not been revised since it was first introduced [18]. Similarly to our study, the Australian study also reported poor performance using the PCCL complexity adjustment on their hospital cost data.

The low performance of the PCCL adjustment in determining average payments using the KDRG may potentially be due to the various factors used to calculate PCCLs, such as the CC list, CCLs [15], and CC exclusion list [21], which have not been updated since their introduction, as stated in the our previous study [19]. Another reason for the poor performance of the PCCL adjustment may be inaccuracy in secondary diagnosis coding [22]. The current coding guideline used in Korea is based on the guidelines used by other countries for statistical purposes to determine the prevalence and mortality of disease and not for DRG-based payments [23]. It is currently revised and issued by the National Statistical Office under the Ministry of Economy and Finance, not by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. This administrative structure makes it difficult to reflect clinical reality in various healthcare fields in the guideline.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. The results of the study may not be generalizable to the total patient population covered by the new DRG-based PPS or may not represent all of the AADRGs in the KDRG because of the small sample collected from a single hospital. Our research showed poor performance of the complexity adjustment mechanism in the KDRG system, despite the fact that the hospital that conducted this research has a greater proportion of patients with more common and moderate-complexity diseases than tertiary hospitals. This suggests that the performance may be worse in hospitals with a more complex patient case mix. Access to the claims data related to the new DRG-based PPS pilot project is currently limited to the public. Further studies should be done for validation of the whole AADRG using a sufficient quantity of claims data.

Furthermore, not all the AADRGs were evaluated, as we were limited to the number of DRGs found in our inpatient claims database. We may have overestimated AADRGs with not valid pattern analysis. However, we tried to ensure the statistical power by including the AADRGs which had sample sizes greater than or equal to the minimum size calculated by G*Power.

Lastly, we assessed the validity of the PCCL adjustment with the KDRG system on the medical charges and not the cost [24]. The fee-for-service charge was set up including payments for hospitals and doctors under government control and was used as a proxy to identify resource consumption. Because there are no cost data for medical services in Korea, we are not able to suggest data for them. The government is planning to collect cost data from the hospitals that participated in the new KDRG project.

Significance

In most countries, DRG is used mainly as a basis for budget allocation to increase the transparency and efficiency of medical services [25]. In Korea, however, under the existing fee-based payment system, DRG was introduced to expand health insurance coverage by controlling uninsured medical services and to contain the rapidly increasing trend in national medical expenditure. The predetermined DRG fee for each disease group is paid directly to healthcare providers for their services. As of April 2020, there were 52 private hospitals participating in the new DRG-based PPS pilot project, with the government providing up to 30% policy participation incentives to hospitals. According to hospitals that have participated in the pilot project, the hospitals have negative revenue after excluding participation incentives [26, 27]. This indicates that the compensation for the provision of medical services based on the PCCL adjustment in the KDRG classification system does not cover the true medical costs. By 2022, however, participation incentives for the new DRG-based PPS are expected to decrease. Thus, hospitals will be reimbursed for inpatient services solely on the DRG-specific fees calculated based on the cost currently being collected by the government.

The most accurate and appropriate compensation using the new DRG-based PPS can be determined with a stable patient classification system, a reasonable complexity adjustment mechanism, and cost data.

The severity adjustment mechanism in the DRG contributes to ensuring homogeneity within disease groups, and it is especially important to improve the accuracy of payment when it used as a payment unit. Experts argue for quickly replacing the fee-for-service system with the new DRG-based PPS to stabilize the rapid increase in national medical expenditure and to increase health insurance coverage [28]. Considering the expansion of the application of the new DRG-based PPS pilot project to 200 medical institutions including private hospitals by 2022, it is importance to ensure payment accuracy using the new DRG-based PPS by evaluating whether the PCCL mechanism for adjusting the patient-level complexity is functioning properly in the KDRG [29]. Therefore, we need to prepare for the financial problems of the Korean healthcare system that may be caused by improper classification when introducing a new payment system.

Conclusion

The poor performance of PCCLs, a mechanism for patient-level complexity adjustment, in the KDRG system suggests that there should be an overall review of the validity and rationality of using the PCCLs in the KDRG classification system for reimbursement.

Although changes in the payment mechanism for providers is inevitable, stabilization and rationality of the system’s components must be ensured, as the payment system is a factor that can affect the providers, insurers, and ultimately the patients. Therefore, when designing systems and implementing policies, policy-makers should take a more cautious approach considering their long-term impact.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the nature of the data owned by the medical institution but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DRG:

-

Diagnosis-related groups

- PPS:

-

Prospective payment system

- KDRG:

-

Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups

- US R-DRG:

-

United States Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups

- AR-DRG:

-

Australian Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups

- CC:

-

Complications and comorbidities

- PCCL:

-

Patient clinical complexity level

- RDRG:

-

Refined diagnosis-related group

- AADRG:

-

Age adjacent diagnosis-related group

- CCL:

-

Comorbidities and complications level

- HIRA:

-

Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service

- ADRG:

-

Adjacent diagnosis-related group

- MDC:

-

Major diagnostic category

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

References

Pass T. Case-mix, severity systems provide DRG alternatives. Healthcare Financial Manage J Healthcare Financial Manage Assoc. 1987;41(7):74–6.

Munoz E, Barrios E, Johnson H, Goldstein J, Mulloy K, Chalfin D, et al. Race and diagnostic related group prospective hospital payment for medical patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 1989;81(8):844–8.

Jones KR. Predicting hospital charge and stay variation: the role of patient teaching status, controlling for diagnosis-related group, demographic characteristics, and severity of illness. Med Care. 1985:220–35.

Lichtig LK, Knauf RA, Parrott RH, Muldoon J. Refining DRGs. The example of children’s diagnosis-related groups. Med Care. 1989;27(5):491–506.

Calore KA, Iezzoni L. Disease staging and PMCs. Can they improve DRGs? Med Care. 1987;25(8):724–37.

McMahon LF Jr, Newbold R. Variation in resource use within diagnosis-related groups. The effect of severity of illness and physician practice. Med Care. 1986;24(5):388–97.

Horn SD, Sharkey PD, Chambers AF, Horn RA. Severity of illness within DRGs: impact on prospective payment. Am J Public Health. 1985;75(10):1195–9.

Patris A, Gomez S, Mendelsohn M, editors. Refined French DRG with four severity levels. BMC health services research; 2008: Springer.

Halpine S, Ashworth M, editors. Measuring case mix and severity of illness in Canada: case mix groups versus refined diagnosis related groups. Healthcare management forum; 1993: Elsevier.

Hughes JS, Lichtenstein J, Magno L, Fetter RB. Improving DRGs: use of procedure codes for assisted respiration to adjust for complexity of illness. Med Care. 1989:750–7.

Jackson T, Dimitropoulos V, Madden R, Gillett S. Australian diagnosis related groups: drivers of complexity adjustment. Health Policy. 2015;119(11):1433–41.

Park EC, Lee SH, Lee SG. The US experience of the DRG payment system and suggestions to Korea. Korea J Hospital Manage. 2002;7(1):105–20.

Kang GW, editor Reform of Korea’s Provider Payment System: Significance and Major Issues of Introducing the New DRG-based Prospective Payment System. The conference of Korean Academy of Health Policy and Management; 2010.

Kim MY. Current situation and future challenges of New DRG-based Prospective payment system. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, 2017. Report No.: 1976-4650.

Kang GW, Park HY, Shin YS. Refinement and evaluation of Korean diagnosis related groups. Health Policy Manage. 2004;14(1):121–47.

Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. KDRG version 3.5 Definition Manual. 2014.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Analysis of hospital-acquired diagnoses and their effect on case complexity and resource use. 2013.

Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. Review of the AR-DRG Classification Case Complexity Process: Final Report. 2014.

Kim SJ, Jung CY, Yon JH, Park HS, Yang HS, Kang H, et al. A review of the complexity adjustment in the Korean Diagnosis-Related Group (KDRG). Health Inform Manage J. 2020;49(1):62–8.

G*power. G * Power 3.1 manual. Unpublished work. 2017.

Industry-Academic Cooperation Foundation of Chungbuk National University, Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Research to improve the severity mechanism of the KDRG—Focus on improving CC Exclusion. 2014.

Mullin RL. Diagnosis-related groups and severity: ICD-9-CM, the real problem. JAMA. 1985;254(9):1208–10.

National Statistical Office. Korean coding standards for classification disease and cause of death. In: National Statistical Office, editor. 2016.

Finkler SA. The distinction between cost and charges. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(1):102–9.

Busse R, Geissler A, Aaviksoo A, Cots F, Häkkinen U, Kobel C, et al. Diagnosis related groups in Europe: moving towards transparency, efficiency, and quality in hospitals? BMJ. 2013;346:f3197.

Lee JW. Reduction of uncovered medical services through the new DRG-based PPS, but the effect of reducing medical expenditure is not clear. Med News. 2020. http://www.bosa.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=2123824. Accessed 15 March 2021.

Kang JG, Kim SH, Shin DGP, Eun Cheol. A Study on the evaluation of the New DRG-based PPS pilot project and the change of accuracy of payment according to model improvement. The national health insurance service Ilsan Hospital; 2016.

Heo JY. The New DRG-based Proactive Payments Sustem will be expanded from August. Chosun Biz. 2018. https://biz.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/07/30/2018073001541.html. Accessed 7 April 2020.

Seongho M. Additional 37 private hospitals particitate in the New DRG based Prospective Payment System. Medical Times. 2019. https://www.medicaltimes.com/Users/News/NewsView.html?ID=1124683. Accessed 27 February 2019.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was developed under the direction of the Korean Association of Internal Medicine (KAIM) Committee and Internal Medicine Health Insurance Policy Agency Committee, which approved the scope of this analysis and provided the peer review. The member list of committees is as follows: (1) YoungSam Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine; (2) HyungJoon Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University; (3) ChangWon Kang, Dr. Kang’s Clinic of Internal Medicine; (4) SeongNam Kim, Dr. Kim’s Medical Clinic; (5) HyungJong Kim, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University School of Medicine; (6) InSeok Lee, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea; (7) ChanSeok Park, Catholic University of Korea; (8) ByungOk Kim, Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital; (9) JaeMyung Cha, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine; (10) IlKwun Chung, Cheonan Hospital, Soonchunhyang University; (11) DongWoon Jeon, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital; (12) JaeWon Jeong, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital; (13) Chon Hwa Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Sejong General Hospital; (14) YeungChul Mun, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine; (15) KeunSeok Lee, Center for Breast Cancer, National Cancer Center; (16) MiSuk Lee, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee University Hospital; (17) HyunAh Kim, Department of Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital; (18) Sungdo Moon, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital; (19) JoonYoung Song, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine; (20) Sun Kyun Cho, BEST Internal Medicine Clinic; (21) TaeBin Kim, Dr Kim’s Clinic of Internal Medicine; (22) HyeJin Yoo, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine; (23) JangWon Son, Department of Internal Medicine, Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea; (24) KyeongHye Park, Department of Internal Medicine, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Republic of Korea; (25) DongYeob Shin, Department of Internal Medicine, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea; (26) DaeYoung Cheung, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine; (27) JoungHo Han, Chungbuk National University & Hospital; (28) MoonHyoung Lee, Yonsei University College of Medicine; (29) DongJin Oh, Department of Cardiology, Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University; (30) BoYoung Yoon, Inje University, Ilsan Paik Hospital; (31) ByungKyu Park, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital; (32) HyunWoong Lee, Department of Internal Medicine, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine; (33) YoungWoong Won, Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University Guri Hospital; and (34) Yong Il Hwang, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital.

Funding

The author(s) disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Korean Association of Internal Medicine (KAIM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJ is the first author of the paper, and reviewed related papers, analysed the data, and wrote most of the paper. BY and KH contributed to the data management, data analysis, and interpretation of the results. SM reviewed and gave helpful comments on the English version of the paper. SI directed the overall study and is the guarantor for the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Adherence to national and international regulations

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

The Structure of the Korean DRG classification and Refinement steps of ADRG based on secondary diagnosis.

Additional file 2.

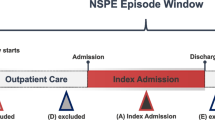

The diagram of analysis method.

Additional file 3.

Criteria used to classify validity patterns.

Additional file 4.

Examples of validity pattern analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Choi, B., Lee, K. et al. Assessing the performance of a method for case-mix adjustment in the Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups (KDRG) system and its policy implications. Health Res Policy Sys 19, 98 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00739-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00739-5