Abstract

Background

Partnerships between academic researchers and health system leadership are often promoted by health research funding agencies as an important strategy in helping ensure that funded research is relevant and the results used. While potential benefits of such partnerships have been identified, there is limited guidance in the scientific literature for either healthcare organisations or researchers on how to select, build and manage effective research partnerships. Our main research objective was to explore the health system perspective on partnerships with researchers with a focus on issues related to the design and organisation of the health system and services. Two structured web reviews were conducted as one component of this larger study.

Methods

Two separate structured web reviews were conducted using structured data extraction tools. The first review focused on sites of health research bodies and those providing information on health system management and knowledge translation (n = 38) to identify what guidance to support partnerships might be available on websites commonly accessed by health leaders and researchers. The second reviewed sites from all health ‘regions’ in Canada (n = 64) to determine what criteria and standards were currently used in guiding decisions to engage in research partnerships; phone follow-up ensured all relevant information was collected.

Results

Absence of guidance on partnerships between research institutions and health system leaders was found. In the first review, absence of guidance on research partnerships and knowledge coproduction was striking and in contrast with coverage of other forms of collaboration such as patient/community engagement. In the second review, little evidence of criteria and standards regarding research partnerships was found. Difficulties in finding appropriate contact information for those responsible for research and obtaining a response were commonly experienced.

Conclusion

Guidance related to health system partnerships with academic researchers is lacking on websites that should promote and support such collaborations. Health region websites provide little evidence of partnership criteria and often do not make contact information to research leaders within health systems readily available; this may hinder partnership development between health systems and academia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The need for collaborative research approaches to address the many and complex problems currently facing the Canadian healthcare system is increasingly recognised [1, 2]. In addition to partnerships between researchers from diverse disciplines, intersectoral research teams, which include both researchers and various knowledge users, offer many benefits for improved health service delivery [3,4,5]. While some approaches to knowledge translation focus on transferring findings of research already completed, integrated knowledge translation approaches to research (like participatory research and engaged scholarship) engage researchers and knowledge users (patients, clinicians, local communities, policy-makers, or health system leaders and managers) in meaningful ways throughout the entire research process [6]. Many potential benefits of this approach have been reported for health systems and for the partners involved. Research partnerships may improve the quality of solutions [5] and enhance responsiveness of health services to community needs [7]. Greater research relevance and credibility may result in increased likelihood that research will be applied in practice [8] and have stronger impact [9]. Enhanced research capacity of both researchers and knowledge users [4], greater understanding of partners’ roles [9], personal and professional development [4], and enhanced skills and networks [3, 4, 9] may also result. Awareness of actual and potential benefits of such research partnerships has led to requirements by many major health research funders for greater participation by health system leaders in health research [10,11,12,13]. As a result, many researchers have sought research partners within the health system.

Recent research has found that, while health system leaders and managers often express support for the principles of collaborative research and articulate a number of potential advantages of such partnerships, there is limited guidance for healthcare organisations in how to select, build and manage effective research partnerships [14]. Conditions associated with successful partnerships have been identified [5, 8, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], but research on this subject is often based on assumptions of researcher-driven initiatives [23] and fails to include health system leaders’ perspectives [24]. Very little is known about strategies for initiating and maintaining partnerships between health organisations and academic researchers to address issues of system organisation [25] – the focus of our study.

Our study

“Building and Managing Effective Partnerships in Canadian Health Systems Research” (Ingrid Botting, P.I.) is a multi-phase, mixed-methods pan-Canadian study exploring how health systems partner with researchers relative to the design and organisation of the health system and health services [26]. As a first step in this research programme, the research team decided to identify current resources available to support research partnership development as well as to undertake a scan of how health regions across Canada were responding to increasing expectations of health system/academic partnerships. As an initial review of the scientific literature highlighted limited guidance in operationalising partnerships [14], the team decided to undertake a review of the grey literature to identify other potential resources available to support health systems in such research collaborations. This was followed by a review of health region public websites to determine what criteria, requirements or standards of practice were required of researchers for research partnerships to be considered. Ethics approval was received from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board.

Methods

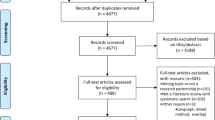

Content analysis of two website types was conducted. Research team members, all with integrated knowledge translation expertise in health services, provided oversight of all phases of the study. Activities were conducted between November 2017 and April 2018. Each of the two web reviews is described separately below.

Web review 1 (Health system support)

This review aimed to identify resources or guidance for research partnerships published on websites believed by the research team to be those most likely to be accessed by either health leaders or researchers interested in research partnerships. Additional sites were included as they were identified. These sites included Canadian and well-known international websites that (1) address issues of health system organisation and functioning, (2) are home to Canadian research funding bodies or (3) are sponsored by organisations promoting knowledge translation or evidence use in healthcare.

Inclusion criteria for the resources selected within these sites was that they addressed both health system change/health service organisation and the practical issues of ‘how to’ establish or manage health system/academic partnerships. Exclusion criteria were resources that (1) were limited to clinical research, researcher relationships with communities or individuals, or collaboration only among academic researchers; (2) were limited to end-of-project (knowledge transfer) activities; or (3) addressed only knowledge user capacity-building or assessment of research capacity. All pages of each site were reviewed; initial selection of potential resources was done by title or description. Resources linked to these sites were also reviewed. All applicable resources were assessed according to a standardised template reflecting principles for effective research partnerships identified through the literature and such items included recognition of stages and diversity of partnerships, recognition of challenges in initiating and maintaining research partnerships, and presence of specific guidance for health systems in establishing and promoting effective research team work (see Additional file 1).

Web review 2 (Canadian health regions)

This second review explored websites of all Canadian health regions (n = 64). These structures, which include regional health authorities, provincial health delivery bodies, local health integration networks and the Integrated Health and Social Service Centres (CISSS) and Integrated University Health and Social Service Centres (CIUSSS) of Quebec, are diverse in structure and size, and reflect the provincial responsibility for health service provision found in Canada. Sites specific to hospital or health centres were excluded as the focus was on regional organisation. This review focused on (1) evidence of research partnerships by health regions; (2) messages targeted to potential research collaborators; (3) extent to which regional review processes demonstrate requirements for partnership, offer guidance or address partnership issues; and (4) accessibility of information relevant to research partnerships for academic researchers (i.e. contact information for research personnel).

All pages of each site were reviewed using a standard template exploring and documenting the following elements: stated commitment to research and interest in collaborating with academic researchers; evidence of research collaboration; evidence of guidance for research partnerships; and overall messaging related to the importance of research, evidence use and knowledge translation activities (see Additional file 2). Availability of research support services, as well as information and submission forms pertaining to research review processes such as impact and access assessment, ethical review within organisations and formal approval by a Research Ethics Board, were noted.

As it was recognised that regions may be using resources not linked to the public websites, key research contact information was retrieved; email or telephone follow-up to each region was conducted to confirm that all relevant publicly available information had been collected pertaining to research collaboration and guidance to support research partnerships.

Analysis

Directed content analysis [27] was used to review, analyse and synthesise website content [28]. This method was chosen as it is unobtrusive, context sensitive, simple and economical [28]. This research method uses prior research as guidance for developing initial codes, which are revised and refined as analysis proceeds. A systematic classification process was conducted by coding; themes and patterns were also identified. Separate structured extraction templates, based on evidence of factors related to effective partnerships [14, 29,30,31], were developed by team members for each of the two reviews.

The templates developed for review served as the data extraction tools for each web review. Qualitative analysis was conducted using a deductive approach [32]. Analysis and synthesis of data sources for the first review was conducted by one researcher; other team members undertook a second review of select sites. Analysis and synthesis for the second review was conducted by two researchers, in consultation with the research team members. A summary matrix was created for regional data collected to facilitate synthesis and quantification of data collected through the review. The process of contacting individuals responsible for research was also documented. When direct contact information was not provided, staff directories, online searches or general enquiry phone numbers or email addresses were used. Up to two follow-up attempts were made after the initial request for information. Frequencies and percentages, calculated with Excel (Microsoft 2010), were used to report quantitative findings.

Results

Web review 1 (Health system support)

Limited resources to guide research partnerships

While many websites referred to partners, collaborations or sponsors, few resources providing guidance for effective health system-research partnerships were found; most of those found provided only minimal guidance and were not developed for use by health leaders.

In total, 38 websites were assessed; from these, 46 potential resources guiding partnerships were identified. Of these, only 12 met criteria to merit a full review and only 10 provided concrete guidance. None was written specifically for health system leaders; however, 4 were written for a general or unspecified audience. Most audiences identified were researchers [6], policy-makers [3] or other audiences [2]. Seven noted that research may be health system initiated; however, no guidance was given. Most [9] provided some suggestions for establishing partnerships, but few of these were comprehensive and only two gave more than a few suggestions for promoting effective teams. Four focused on international development work. Two were short, recent blog posts. Only one resource directly addressed the topic of our research.

Most resources (such as webinars, courses or tools) intended for knowledge users focused on developing research-related skills of health personnel; few addressed relationship building or the skills needed to establish meaningful partnerships or influence research agendas.

Absence of resources for knowledge coproduction

The concept of knowledge translation (including terms such as knowledge transfer, knowledge to action or knowledge mobilisation) was found frequently in this review. Some useful links were provided to knowledge translation theory. However, knowledge transfer (referring to strategies to communicate research results on research already completed) remained the dominant approach found in resources reviewed. Resources to support knowledge coproduction were conspicuous by their absence.

Web review 2 (Canadian health regions)

Limited evidence of research partnerships

Overall, there were limited references to research collaborations or to a role in research in the review of health region sites. Generally, there was limited mention of, or reference to, either research or commitment to evidence-informed system design or organisation. Of the 64 health region websites, 38 (59.4%) made no mention of research on the front page. Few mission or vision statements mentioned a commitment to knowledge-to-action strategies (i.e. knowledge transfer, knowledge translation/mobilisation) (n = 16, 25%), evidence (n = 17, 26.5%) or research (n = 7, 10.9%).

Involvement in research collaborations was noted on approximately half the websites (n = 31, 48.4%), although specific examples generally referred to research of a clinical, basic science or community/population health nature. Formal affiliation to universities or research institutes was more evident in Quebec websites, as were examples of research collaborations. As might be expected, rural and remote health regions across Canada were the least likely to address research collaboration with academic researchers. These regions were more likely to provide information on community engagement, and regions with a large indigenous population were most likely to provide links to and emphasis on using specific ethical guidelines for research with indigenous peoples.

There was a striking absence of evidence in this web review of (1) stated requirement for partnership, (2) criteria for engaging in health organisation research partnerships and (3) assessment of collaboration between health regions and researchers. Only two of the 64 regions (3.1%) provided any evidence of guidance around research partnerships above standard review requirements, although many did state a requirement for organisational or programme approval. Less than one quarter (n = 15, 23.4%) provided website information related to research support or facilitation services offered by the region. Information of research review processes was readily accessible on 39.1% of websites (n = 25). The majority of sites of large- and medium-sized health regions provided research review contact information or guidelines and/or forms for ethics, research and access reviews; information on research review processes and application forms, where available, were remarkably similar.

Limited accessibility of health regions to researchers

Challenges were experienced in both identifying and contacting individuals responsible for research in the majority of health regions. Responsibility for research was often unclear and direct research-related contact information was often not provided (n = 45, 70.3%). Attempts to connect with the identified person on the website were successful in less than 30% of cases. Median wait time for response was prolonged (18 days). In 25% of cases, no response was received, even after a minimum of three attempts at making contact with the individual responsible for research (in some cases, these attempts were in addition to contacts made to identify this individual) over a 10-week period. Email appeared to be more effective than telephone contact. Proceeding through a general phone number or website form was least successful – individuals answering often did not know who to refer to for research questions and some did not respond at all. Where the only contact was an ethics or research review committee, delays in response to requests for contact were also common.

Discussion

These two web reviews were undertaken as preliminary activities to inform a larger programme of research designed to explore health system perspectives on research partnerships with academia on topics related to health system organisation. Some of the results reported here were unexpected and provide insight into potential barriers to such collaborations. Consistent with preliminary findings of a scientific literature review [14], few resources or guidance in how to establish and successfully manage research partnerships are made available through health system support websites. Furthermore, an absence of evidence of research partnerships with a specific focus on health system design and organisation and criteria required by researchers to collaborate with health systems was observed in the review of Canadian health region websites. While a number of authors have acknowledged similar challenges in initiating and implementing multi-sectoral actions [33, 34], there appears to be less attention given to health system and research partnerships. The absence of specific guidance and concrete examples of successful collaborations focused on health system organisation suggests that effective research partnerships may not be currently viewed as a priority by health organisations.

While recent research stresses the importance of entering partnerships with health leaders early on in the process to improve research relevance and use [15, 18, 22], the majority of resources identified on health system support websites focused simply on dissemination of research at the end of the study (knowledge transfer or end-of-project knowledge translation) rather than on coproduction of research reflecting user concerns. This suggests that research findings may not have been integrated into materials currently available. In addition, most resources were directed to researchers or ‘knowledge translation’ practitioners rather than to health system leadership.

There does, however, appear to be some indication that change may be occurring, and that more attention to ‘coproduction’ may be emerging. For example, leading international organisations, such as the WHO Alliance for Health Care Policy and Systems Research [35], are providing consistent aspirational statements about the importance of meaningful collaboration between the health system and researchers while appearing to move away from an emphasis on simple, one-way research knowledge transfer. Such documents and dialogue that these efforts spur may provide a needed foundation for practical steps to support health system leaders in initiating and managing research partnerships.

Recognising that public websites of health regions may not post all relevant information either in report form or links to guidelines, we attempted to confirm, with appropriate contacts from each region, whether additional materials were used. However, these follow-up requests did not result in additional materials being found with respect to either evidence of research partnerships or processes supporting such collaborations. Furthermore, contact with personnel within the health system with responsibility for research and/or relationships with academic researchers proved challenging. The difficulty in identifying and making contact with these individuals suggests that academic researchers may face significant barriers in identifying and establishing relationships with potential health system partners.

The observation that academic/health system partnerships appeared to be more apparent in Quebec may reflect the fact that, following the systemic integration of health and social services in 2015, Integrated University Health and Social Service Centres were created, improving visibility of the academic role in both research and education within those health regions. However, further research is required to determine whether these formal academic affiliations have led to greater research collaboration, or whether such affiliations have been more receptive to system-prioritised research.

In general, absence of information on research/health system partnerships in both reviews was in clear contrast to the presence of general information and specific guidance and information for health systems to engage in partnership with a number of other key stakeholder groups. More information and guidance was found on community engagement, particularly for engaging with indigenous communities (e.g. Canadian Institute of Health Research 2013) [36]; patient engagement (e.g. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement 2018) [37]; and research and policy relationships in an international development context (e.g. Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research 2017) [38] as well as professional, inter-professional and inter-organisational collaboration (e.g. Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue 2010) [39]. Reasons for this disparity in coverage require further investigation.

A limitation to the review of health region websites is that content of publicly accessible messages provided on health region websites may not accurately reflect all initiatives or resources. However, as previously noted, follow-up requests for information made to research personnel in these regions confirmed the absence of specific guidelines for partnerships in most regions. This limitation does not apply to the first (health system support) review as the websites analysed would be those most likely to be consulted by health leaders and researchers. Another limitation of both reviews is that frequency of website updates and redesign means that results of such reviews could vary on a monthly basis. Monitoring of several sites since the reviews were completed indicates, however, that the observed trends are still apparent.

Conclusion

This research, consisting of two focused web reviews, found an absence of identifiable guidance related to health system/academic research partnerships in websites that could be expected to provide resources and support for such collaborations. This finding does not reflect the priority given to research partnerships by many health research funding agencies. Canadian health region websites provide little evidence not only of research partnerships pertaining to health system organisation but also of research partnership criteria in contrast to attention directed towards other forms of partnerships. Difficulties in determining research contacts within health regions are common and may present challenges in the formation of research collaborations. Further research is needed to gain insight into whether Canadian health leaders partner with academia and which strategies are used to foster such partnerships.

Availability of data and materials

A list of all websites accessed for web review 1 (Health system support) could be made available; however, the rapidly evolving nature of websites would not necessarily enable replication of what resources were posted.

A dataset was created for web review 2 (Canadian Health Regions); however, for confidentiality and ethical considerations, we are unable to make this dataset available as it includes names of informants and specific regions. Furthermore, some health regions have changed (for example, amalgamation in Saskatchewan) since the review was undertaken; results could therefore not necessarily be replicated in all regions.

Copies of the data extraction sheets for both reviews are provided in the additional files.

References

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. Assessing Initiatives to Transform Healthcare Systems: Lessons for the Canadian Healthcare System. 2011. https://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/Libraries/Commissioned_Research_Reports/JLD_REPORT.sflb.ashx. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Canadian Medical Association. Improving the Health of all Canadians: A Vision for the Future – The CMA’s Platform on the 2017 Federal/Provincial/Territorial Health Accord. 2017. https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/News/improving-the-health-of-all-canadians-a-vision-for-the-future.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Brazil K, Ozer E, Cloutier MM, Levine R, Stryer D. From theory to practice: improving the impact of health services research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-5-1.

Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, Salsberg J, Bush PL, Henderson J, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012;90(2):311–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x.

Wildridge V, Childs S, Cawthra L, Madge B. How to create successful partnerships-a review of the literature. Health Inf Libr J. 2004;21(Suppl 1):3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-3324.2004.00497.x.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Guide to Knowledge Translation Planning at CIHR: Integrated and End-of-Grant Approaches. 2012. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/kt_lm_ktplan-en.pdf. Accessed 6 Jun 2018.

Durey A, McEvoy S, Swift-Otero V, Taylor K, Katzenellenbogen J, Bessarab D. Improving healthcare for Aboriginal Australians through effective engagement between community and health services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1497-0.

Sibbald SL, Tetroe J, Graham ID. Research funder required research partnerships: A qualitative inquiry. Implementation Sci. 2014;9:176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0176-y.

Walter I, Davies H, Nutley S. Increasing research impact through partnerships: evidence from outside health care. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(Suppl 2):58–61. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581903322405180.

Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2.

Smits P, Denis JL. How research funding agencies support science integration into policy and practice: an international overview. Implementation Sci. 2014;9:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-28.

Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R, Robinson N, Eccles MP, Wensing M, et al. Health research funding agencies’ 15 support and promotion of knowledge translation: an international study. Milbank Q. 2008;86(1):125–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00515.x.

Traynor R, Dobbins M, DeCorby K. Challenges of partnership research: Insights from a collaborative partnership in evidence-informed public health decision making. Evid Policy. 2015;11:99–109. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426414X14043807774174.

Bowen S, Botting I, Graham ID, Huebner LA. Beyond “two cultures”: guidance for establishing effective researcher/health system partnerships. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6(1):27–42. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2016.71.

Bowen S, Martens PJ. The need to know team. Demystifying knowledge translation: learning from the community. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(4):203–11. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581905774414213.

Bullock A, Morris ZS, Atwell C. Collaboration between health services managers and researchers: making a difference? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17(Suppl 2):2–10. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2011.01109.

Casey M. Partnership--success factors of interorganizational relationships. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(1):72–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2934.2007.00771.x.

Golden-Biddle K, Reay T, Petz S, Witt C, Casebeer A, Pablo A, et al. Toward a communicative perspective of collaborating in research: the case of the researcher-decision-maker partnership. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(Suppl 2):20–5. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581903322405135.

Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, Macaulay AC, Greenhalgh T, Wong G, et al. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:725. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1.

Pinto RM. What makes or breaks provider-researcher collaborations in HIV research? A mixed method analysis of providers’ willingness to partner. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(2):223–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198112447616.

Rycroft-Malone J, Wilkinson J, Burton CR, Harvey G, McCormack B, Graham I, et al. Collaborative action around implementation in collaborations for leadership in applied health research and care: Towards a programme theory. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(3 Suppl):13–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819613498859.

Salsberg J, Parry D, Pluye P, Macridis S, Herbert CP, Macaulay AC. Successful strategies to engage research partners for translating evidence into action in community health: a critical review. J Environ Public Health. 2015;2015:191856. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/191856.

Kothari A, Wathen CN. A critical second look at integrated knowledge translation. Health Policy. 2013;109(2):187–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.11.004.

Bartunek JM, Rynes SL. Academics and practitioners are alike and unlike: the paradoxes of academic-practitioner relationships. J Manag. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314529160.

Talbot C, Talbot C. Bridging the academic - policy-making gap: Practice and policy issues. Public Money Manag. 2015;35(3):187–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2015.1027491.

Graham IA, Kothari A, McCutcheon C. Moving knowledge into action for more effective practice, programmes and policy: protocol for a research programme on integrated knowledge translation. Implementation Sci. 2018;13:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0700-y.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Kim I, Kuljis J. Applying content analysis to web-based content. J Comput Inf Technol. 2010;4:369–75. https://doi.org/10.2498/cit.1001924.

Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Ann Rev Public Health. 2008;29:325–50. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824.

Gagliardi AR, Dobrow MJ. Identifying the conditions needed for integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care organizations: qualitative interviews with researchers and research users. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:256. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1533-0.

Hofmeyer A, Scott C, Lagendyk L. Researcher-decision-maker partnerships in health services research: practical challenges, guiding principles. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:280. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-280.

Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002.

Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Millbank Q. 2001;79(2):179–205, III–IV. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00203.

Kraak VI, Harrigan PB, Lawrence M, Harrison PJ, Jackson MA, Swinburn B. Balancing the benefits and risks of public-private partnerships to address the global double burden of malnutrition. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(3):503–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011002060.

World Health Organization. Alliance for Health Care Policy and Systems Research. Partnerships and Networks. 2018. http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/partners/en/. Accessed 6 Jun 2018.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CIHR Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People (2007–2010). 2013. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29134.html. Accessed 11 Sep 2018.

Canadian Foundation for Health Improvement. Patient Engagement Resource Hub. 2018. https://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/WhatWeDo/PatientEngagement/PatientEngagementResourceHub/Results.aspx. Accessed 11 Sep 2018.

Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research. Resources. 2017. http://www.ccghr.ca/resources/. Accessed 11 Sep 2018.

Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue. Cadre de référence balisant les relations entre les établissements du Réseau de la santé et des services sociaux, l’agence et les organismes communautaires. 2010. http://www.cisss-at.gouv.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CADRE_DE_REFERENCE_2010-09-29.pdf. Accessed 10 Sep 2018.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research foundation grant ‘Moving knowledge into action for more effective practice, programs and policy: a research program focusing on integrated Knowledge’, Inaugural competition, FDN #143237.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB and IB conducted web review 1 (Health system support review). SB and DM conducted web review 2 (Canadian Health Regions review), with the assistance of CMS and MB for follow-up phone calls. IG, MM and KH provided oversight in all steps of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was received from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (#HS21241 (H2017:358)).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Extraction table for review of web resources for health systems. (DOCX 508 kb)

Additional file 2:

Extraction table for review of Canadian health regions’ websites. (DOCX 497 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Moissac, D., Bowen, S., Botting, I. et al. Evidence of commitment to research partnerships? Results of two web reviews. Health Res Policy Sys 17, 73 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0475-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0475-5