Abstract

Introduction

Rural pipeline approach has recently gain prominent recognition in improving the availability of health workers in hard-to-reach areas such as rural and poor regions. Understanding implications for its successful implementation is important to guide health policy and decision-makers in Sub-Saharan Africa. This review aims to synthesize the evidence on rural pipeline implementation and impacts in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using Joanna Briggs Institute guidebook. We searched in PubMed and Google scholar databases and the grey literature. We conducted a thematic analysis to assess the studies. Data were reported following the PRISMA extension for Scoping reviews guidelines.

Results

Of the 443 references identified through database searching, 22 met the inclusion criteria. Rural pipeline pillars that generated impacts included ensuring that more rural students are selected into programmes; developing a curriculum oriented towards rural health and rural exposure during training; curriculum oriented to rural health delivery; and ensuring retention of health workers in rural areas through educational and professional support. These impacts varied from one pillar to another and included: increased in number of rural health practitioners; reduction in communication barriers between healthcare providers and community members; changes in household economic and social circumstances especially for students from poor family; improvement of health services quality; improved health education and promotion within rural communities; and motivation of community members to enrol their children in school. However, implementation of rural pipeline resulted in some unintended impacts such as perceived workload increased by trainee’s supervisors; increased job absenteeism among senior health providers; patients’ discomfort of being attended by students; perceived poor quality care provided by students which influenced health facilities attendance. Facilitating factors of rural pipeline implementation included: availability of learning infrastructures in rural areas; ensuring students’ accommodation and safety; setting no age restriction for students applying for rural medical schools; and appropriate academic capacity-building programmes for medical students. Implementation challenges included poor preparation of rural health training schools’ candidates; tuition fees payment; limited access to rural health facilities for students training; inadequate living and working conditions; and perceived discrimination of rural health workers.

Conclusion

This review advocates for combined implementation of rural pipeline pillars, taking into account the specificity of country context. Policy and decision-makers in sub-Saharan Africa should extend rural training programmes to involve nurses, midwives and other allied health professionals. Decision-makers in sub-Saharan Africa should also commit more for improving rural living and working environments to facilitate the implementation of rural health workforce development programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global shortfall of health workers (HWs) was estimated at 15 million in 2020 [1]. A quarter of this need-based shortage is found in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region; sorely confronted with endemic health problems (Malaria, HIV/AIDS, TB, etc.) and recurrent outbreaks of re-emerging infectious diseases, such as Ebola, Covid-19 [2, 3]. The inequitable distribution of HWs found between SSA and other regions of the world is likewise reflected within SSA countries and rural, peri-urban and urban locations [4]. Nowadays, most SSA countries display serious imbalances of HWs distribution between rural and urban areas, such that half of rural population are denied essential healthcare services [5]. This situation hinders healthcare systems capabilities in SSA to achieve high and effective coverage of health services [6]. Moreover, as epidemiological transition becomes obvious, and demographic change irreversible in SSA, predictions sustain that healthcare demands and needs in this region will grow at an unprecedented pace in the nearby future [7, 8]. Hence, the need to improve the availability and employment of qualified and fit-for purpose HWs in SSA, especially in rural and remote locations, is more imperative now than ever [9].

In an effort to improve HWs development, attraction, recruitment, and retention in rural and remote areas, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended set of strategies including those pertaining to the development of HWs. Notably, targeted admission policies to enrol students with a rural background in HWs education programmes; locating health education facilities closer to rural areas; exposing students of a wide array of HWs disciplines to rural and remote communities and rural clinical practices; including rural health topics in HWs education. The WHO recommends a policy of having career development and advancement programmes, and career pathways for HWs in rural and remote areas [5]. Together, this comprehensive rural targeting and training in rural areas can be referred as a “rural pipeline” approach [10]. The rural pipeline approach has four tailored pillars: (i) advocating careers in health professions among rural students; (ii) prioritizing the selection of rural students into programmes; (iii) developing a curriculum oriented towards rural health and rural exposure during training and (iv) ensuring retention of HWs in rural areas through educational and professional support [10].

Rural pipeline programmes have yielded positive results in many High-and-Middle Income countries like the USA, Canada, Australia, Sweden, and Norway [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. For instance, authors in the USA have documented the persisting impact of rural pipeline interventions in retaining up to 87% of programmes’ graduates in underserved areas 22 years after their recruitment [20]. In six Northern European countries, including Sweden and Norway, 67% of health professionals under rural pipeline programmes were retained in rural and underserved locations five years after their recruitment [21].

Rural pipeline implementation is relatively new to SSA settings. However, there exists well known documented experiences from countries like South Africa [22], Uganda [23, 24], and Mali [25, 26]. For instance, Dormael and colleagues in their study on recruiting medical doctors to rural districts found that preferential selection of students with rural background and their exposure to rurally relevant training packages enhanced their self-confidence, job-satisfaction and retention during the three years of the project lifespan in rural Mali [27]. Authors have also reported the positive outcomes of rural pipeline programmes on the attitudes, specialty choice, and intentions of HWs to practice in rural areas; and their performance in local health care systems in SSA [28,29,30,31]. Nonetheless, the successful implementation of these strategies are context-dependent. Factors that hinder the sustainability of these strategies include financial, structural and managerial challenges [32, 33].

In a recent systematic review, the WHO has reported on strategies that increase the retention of HWs in rural areas in the global context, including in SSA [5]. However, studies included in this review were unequally distributed across the WHO region, with only 18% from SSA [5]. Additionally, out of the 22 studies selected from SSA, only four were about medical education reform [5]. While this review acknowledged that successful implementation of these strategies are context-dependent, it did not, however, disaggregate findings by WHO region [5]. This raises the need for more in-depth insights of rural pipeline strategies implemented in SSA region, and their impacts.

We therefore undertook this scoping review of the literature relating to the status of rural pipeline programmes implementation and impacts in SSA. Specifically, we attempted to:

-

(a)

To identify rural pipeline strategies/pillars implemented to improve the availability of qualified HWs in rural SSA and their impacts on health services and systems;

-

(b)

To assess facilitators and challenges for the implementation of rural pipeline strategies to improve the availability of qualified HWs in rural SSA.

Methods

Study design

This scoping review uses the guidance document developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [34]. We opted for this study design because of the scope of our research questions, the potential of this methodological approach to map and summarize empirical evidence, and inform future research.

We followed the five stages for scoping review outlined by the JBI manual: (1) identification of research questions; (2) identification of relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) data charting; and (5) results summarizing and reporting [34].

Identification of research questions

For this scoping review, three key research questions were identified: (i) what is known on rural pipeline strategies or its pillars implemented to improve the availability of qualified HWs in rural Africa, (ii) what are the facilitators and challenges for the implementation of rural pipeline strategies to improve the availability of qualified HWs in rural SSA, and (iii) what have been the impacts of rural pipeline strategies on improving the availability of qualified HWs in rural SSA?

Through these questions, we sought to map and summarize the range of rural pipeline interventions undertaken in SSA to improve the attraction and retention of qualified HWs in rural and remote areas.

Identification of relevant studies

We used PubMed and Google scholar databases to search for empirical peer-reviewed literature that reported on rural pipeline interventions for increasing the availability of qualified HWs in rural SSA. These studies were published in English or French. The peer-reviewed literature search strategy was based on the “PCC approach” (Population, Concept and Context) of the JBI guide and included studies from 2000 onwards:

-

Population: This included the formal health workforce taking into account their varying profile (medical doctors or physician, nurses or nurses practitioners, midwives or nurse-midwives, etc.);

-

Concept: search terms included “rural pipeline” or “rural pathways”, ‘rural training pathways’, ‘rural training programme’, ‘rural education’ ‘rural exposure’, ‘rural practice’, ‘rural experience’, ‘rural attraction programme’, ‘rural scholarship programme’; “return to service” programme, rural placement programme, rural retention programme, rural employment programme, rural development programme, or bundled interventions.

-

Context: SSA countries according to WHO countries list.

We also used literature search through WONCA (World Health Organization of Family Doctors) websites and Google. Additionally, we used iterative snowball or citation tracking techniques—that is reviewing reference lists of primary included articles to identify additional relevant studies. These articles were assessed between November 2021 and February 2022.

The principal investigator (DK) carried out the literature search. RvdP reviewed search strategies. All selected references were either saved using PubMed functions, or on Mendeley desktop software.

Study selection

Our search results were cleaned for duplicates by two members of our research team (DK and RvdP) using following eligibility criteria: (i) studies describing rural pipeline strategy or pillar; (ii) studies describing facilitators or challenges of rural pipeline implementation; (iii) studies describing the impacts of the rural pipeline intervention on local health services and communities (e.g. quality of care, health coverage, etc.). Discrepancies in study selection processes were resolved by a discussion between the two reviewers.

Data charting

Data, mainly qualitative, were extracted by the two reviewers (DK and RvdP) using an Excel spreadsheet. This Excel form was piloted on three articles before use. Data collected included: (i) study characteristics—authors name, year of publication, study country and study design; and (ii) information related to implemented interventions—implementation strategies, facilitators or barriers of rural pipeline programmes implementation, and programmes outcomes or effects. Given our research questions, both quantitative and qualitative data analyses were done.

Summarizing and reporting results

Characteristics of included studies were summarized using descriptive statistics. We then used thematic content analysis to sum up the main findings of the review. We reported the results following the PRISMA Extension for Scoping reviews guidelines [35].

Results

Description of studies included in the review

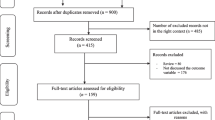

The present review includes 22 studies published between 2007 and 2021, with the majority (fifteen) published from 2015 [29,30,31, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Figure 1 shows the studies selection process. These studies were from eight countries, with South Africa (eight studies [30, 39,40,41, 44, 47,48,49]), Uganda (four studies [23, 24, 43, 46]), Ghana (three studies [36,37,38]) and Mali (three studies [25, 26, 31]) being the most represented. One study was reported from each of the following countries: Malawi [28], Tanzania [42], Bostwana [45] and the Demographic Republic of Congo [29], DRC (Table 1). These were predominantly qualitative (nine studies [23, 24, 26, 29, 30, 44, 46, 47, 49]) and quantitative (five studies [37, 38, 40, 42, 43]) methods studies. Eight studies used a mixed-methods approach [25, 28, 31, 36, 39, 41, 45, 48].

Pillars and impacts of rural pipeline programmes

One more rural pipeline pillar (social accountability) was identified in addition to the four reported by Tesson et al. [10] (advocating health professions among rural students; ensuring that more rural students are selected into programs; developing a curriculum oriented towards rural health and rural exposure during training; curriculum oriented to rural health delivery, and ensuring retention of HWs in rural areas through educational and professional support). We followed the above six pillars of the rural pipeline to report the results; this is why the focus of the paper in the sections that followed may varies from lines to lines, depending on which pillar is being described.

Advocating health professions among rural students

This pillar of the rural pipeline programme includes three main strategies reported from different countries. The first strategy, reported from Mali, is the decentralization of medical schools to the regions (cities in the countryside including rural locations) to favour local medical training [31]; the second, also from Mali, is using radios to announce dates for the start of school programmes [31]; the third strategy was reported from DRC, Ghana and Uganda, and is related to raising awareness of students and their parents about the need and importance of education reform that promote rural pipeline [29, 36, 37, 43].

None of the selected studies for this review directly reported impact of this pillar on health, and socio-economic situations.

Ensuring that more rural students are selected into programs

For this pillar, two strategies have been reported. In Mali, this consisted of organizing admission tests for medical studies in all regions [31]. In Malawi and South Africa, the strategy was to grant scholarship to needy students; that is mostly those with a low socio-economic status [28, 30, 41]. For instance, in South Africa, the scholarship programme increased the number of low socio-economic students enrolled from four (4) in 1999 to 337 over 2017 [30, 41].

This pillar has been documented to favour three impacts. First, it helps to increase the number of rural health practitioners; in Mali, enrolling in medical training programmes students who had secondary school in rural areas was reported to favour health practitioners’ intention and willingness to work in rural areas [31, 41]. Second, this pillar contributes to reducing communication barriers between healthcare providers and community members. Gumede et al. in South Africa have mentioned with the employment of local health practitioners, rural patients access health services without needing interpreters to convey the message to the healthcare practitioners [30]. Practitioners better understand the community needs and provide quality health care. In addition, the lift of communication barrier favours outreach services in course of which practitioners communicate to prevent the spread of diseases in the community [30].

Third, this pillar is reported to contribute to socio-economic development of rural areas. McGregor et al. and Gumede et al. in South Africa reported major changes in household economic and social circumstances of students from poor family after their graduation [30, 41]. Compared to their parents and families were they grew up, graduates were able to buy cars, build decent family houses, send their children to private schools and take care of their siblings [41]. The return on investment of this program in rural South Africa was estimated to be 22 times the cost of the training [41].

Developing a curriculum oriented towards rural health training and delivery

This pillar consists of two main strategies: emphasizing primary care throughout the curriculum [40] and placing students in rural communities and health care settings. Regarding the curriculum, Amalba et al. in Ghana and Strasser et al. in DRC documented that students, before graduation, were trained on how to do community health diagnosis and identify available resources to meet the needs, but also to understand functioning of rural health facilities [29, 37]. In Uganda, Atuyambe et al. said that just before sending students to communities, they are briefed on community health and primary health care at school [46].

For the placement of students in rural communities and health care settings, Amalba et al. reported that the Ghanaian context was marked by Community Based-Education services (COBES) that consisted of dispatching groups of 8–10 students to rural communities and health care settings for four weeks every year, during three consecutive years [37]. In Tanzania and South Africa, students were sent to communities and primary healthcare settings for twelve weeks and six weeks, respectively, each year [42, 44, 47]. In Mali and Bostwana, this pillar consisted of adopting a mandatory last year rural training policy for students. In public and private schools, students at the final year of graduation were required to do practical training in a rural environment, as part of the examination process [31, 45]. The training was planned for 45 and 56 days, in Mali and Bostwana, respectively, under the direct supervision of rural health care providers [31, 45]. In Mali, this training was concluded with a report produced by the student and approved by the teachers [31]. In South Africa, Hatcher et al. reported that a year of compulsory community service was adopted for young health professionals, including medical doctors, dentists and nurses [39]. In South Africa, a similar approach of compulsory service was reported by McGregor et al. whereby graduates who benefit a scholarship during their training were expected to fulfil a year-for-year work-back obligation in rural areas [41].

Six impacts—of which four at the health facility level and two at the community level—are reportedly related to this pillar.

At the facility level, this pillar contributes to increasing rural health practitioners. In Ghana, Amalba et al. found that making students follow a curriculum integrating exposure to rural training and practice increased their willingness to work in rural areas [38]. This pillar also reinforces professional development of health practitioners; on the one hand, the communities to which the students are sent serve as learning platforms where they interact with different cultural backgrounds. Through this way, they improve their communication skills, build their clinical and social skills and empower themselves in their clinical work [36]. On the other hand, sending students to rural care settings for practical training commit senior rural health practitioners to guide the students. This may lead the University to incentivize the senior practitioners by offering some of them admission into the University to pursue studies to better guide students who are acknowledgeable than them [36]. The third impact prospect attributed to this pillar is the improvement of the quality of health services; in South Africa, young practitioners or students deployed in the care settings were told to improve the service delivery by doing more in-depth as well as comprehensive assessments of patients, being able to see patients more regularly than qualifies clinicians [30, 47].

However, increase in rural health workers’ workload and supervisors’ absenteeism rate have been reported as unexpected impacts of this pillar. First, Atuyambe et al. in Uganda reported the placement of students in rural facilities as an extra workload for the rural health workers, as the latter are assigned to supervise students’ practices [46]. Indeed, with the presence of students, senior health workers have to explain to them the practice as they provide care to patients. Besides this being more time consuming, it results in fewer patients being delivered care per day. Second, Atuyambe et al. in Uganda found that some HWs use the presence of students in health facilities as an opportunity to take unofficial leave, hence leaving students unsupervised [46]. This practice was reported to hamper students’ learning capacity.

At the community level, the deployment of medical students into rural communities for practical training has been reported in Ghana and Uganda to contribute to health education and promotion within these communities. Students’ activities in rural communities included communications on drinking water, hand hygiene, good sanitation practices including latrine construction, sexual health and other health issues [36, 46]. Students in Uganda were also told to contribute to the maintenance of safe water sources [46]. In addition, the presence of medical students in rural communities has been documented to motivate the youth who see these students as role model. Indeed, with the presence and perceived usefulness of these medical students, community members realize the relevance of children’s education, thereby encourage them to enrol their children in school [37].

Nonetheless, patients’ discomfort of being attended by students has been reported as an impact of this pillar. A study in Uganda reported that some health managers had difficulties convincing community members to be attended by students as they perceived students as not qualified to provide care [46]. This attitude of communities towards students has been reported to influence health facilities attendance, especially for maternal health services such as birth delivery [46].

Ensuring retention of health workers in rural areas through educational and professional support

This pillar includes four aspects to account for. The first aspect is to ensure that rural health facilities are well equipped to allow smooth functioning of the facility, provision of quality care, thereby allow job-satisfaction of the staffs [30, 31]. This training would strengthen young professionals’ technical competences and self-confidence [25, 26]. The second aspect is to ensure continuous training to meet rural practitioners’ needs. Thirdly, retaining HWs in rural areas requires conducting regular field supervisions to assess, acknowledge, support and encourage rural health practitioners’ work [25, 28]. The fourth aspect is the organization of regular national/regional encounters or reciprocal visits between rural and urban health practitioners to fight professional isolation [25, 28]. Such encounters can be promoted by health professional associations [25].

This pillar has been reported to increase the number of rural health workers; training health practitioners in primary health care was said to retain them in this location. Dormael et al. in Mali reported that 55 out of 65 trained young doctors (85%) deployed in rural areas remained at their location, two years after the training [26]. In addition, retaining health workers in rural areas was reported to yield in social development of health practitioners as they learn the culture and lifestyle of the community, and benefit from the hospitality of community members [38]. Furthermore, some practitioners got married or engaged to local people, thus fulfilling a social endeavour [30].

Ensuring social accountability

Clithero et al. in South Africa reported about social accountability of health professionals as an important part of the rural pipeline [40]. This consists of ensuring that the students enrolled in the training programmes will meet communities’ health needs after graduation. In the South African context, as specific indicators to assess this, education authorities checked whether the students being enrolled have the socio-demographic profiles matching the populations to be served and whether these students choose to practice primary care and intend to practice in areas of high need such as underserved and rural areas. Another strategy for social accountability has been described by Gumede et al. in South Africa [30]. It is to apply an integrated model of student recruitment, which involves enrolling student by local health facility, grating them a scholarship, exposing them to a compulsory structured academic and social mentoring programme, making them attend experiential holiday work at the health facility, and absorbing them into the health facility through which they were enrolled. A complementary approach for this pillar, reported by Kelly et al. in Malawi, is to ensure that scholar students fulfil the service agreement after graduation [28]. In the case of Malawi, the funding agency maintained a close follow up with each scholar through site visits, text messaging, phone calls [28].

None of the selected studies for this review directly reported impact for this pillar.

Factors influencing rural pipeline implementation

Ten studies reported about drivers in implementing rural pipeline program in sub-Saharan Africa [23,24,25, 28, 30, 36, 37, 39, 41]. Seven main drivers emerged from these studies, including availability of medical school and health facility infrastructures in rural areas, assessment of readiness of rural clinics for students’ practical training, mapping of rural sites for students’ accommodation, setting no age restriction for students applying for rural medical schools, appropriate academic capacity-building programmes for medical students, motivational dynamics for students to do their career in rural settings, students’ personal assets for and interest in rural practice, and locking health personal recruitment in urban area.

Availability of medical school and health facility infrastructures has been mentioned in studies from Mali, Uganda and DRC as important facilitator in implementing rural pipeline in these countries. While the existence of 120 schools with medical programmes in Mali has been reported as an asset to promoting health professions in rural areas [30], engagement of five Ugandan medical universities in 2010 to promote equitable health services for all the country’s population was documented to also stimulate rural medical practices in Uganda [43, 46]. In addition, in the DRC, Strasser et al. reported availability of rural health facilities to receive students for practical training as an important aspect to account for in the rural pipeline implementation.

Another reported facilitating factor of the rural pipeline is to ensure students’ accommodation and safety in rural areas. In the DRC, the Ministries of Health and Education proceeded in advance with the identification and preparation of specific rural sites that have the potential of accommodating an influx of students [29]. In Uganda, students recommended the availability of social amenities, affordable cost of living, their personal security in rural areas for their placement there [23].

In Mali, one strategy to promoting the implementation of the rural pipeline was to lift the age limit for candidates who were interested in attending training schools located in rural areas [31].

In South Africa and the DRC, having an appropriate academic capacity-building program for medical students has also been reported as a rural pipeline facilitator. This consists of setting, in rural medical schools, training programmes and supervision strategies that help students to successfully complete the courses and build their capacities such as caring for patients and engaging in teamwork [29, 44].

A set of motivational dynamics has been documented to be useful for implementing rural pipeline in Ghana and Mali. In Ghana, a partnership was built between a university located in the northern region (Tamale School of Medicine and Health Sciences) and community members to increase medical students’ awareness about the importance of working in rural areas [37]. In Mali, teachers from the Faculty of Medicine of Bamako encouraged students to settle in remote areas, sharing their positive experiences with them [26].

In Uganda, HWs said they would only work in rural settings upon active improvement of their wages [43]. As for them the important disparity between the salaries of HWs in urban areas and those in rural areas is a key consideration guiding their choice for their working places [43]. Non-financial incentives have also been reported in Mali as an encouraging strategy used to place health workers in rural areas [26]. These incentives included improving living (water, solar panels, motorbike) and working conditions (basic equipment, continuous education, peer support and mentoring) for young health professionals who accept to settle in rural Mali [26].

Studies from South Africa, Uganda and Ghana mentioned that students’ personal competencies for and interests in rural practice are also key factor to implementing rural pipeline [23, 38, 44]. Referring to competencies, students’ previous exposure to rural health facilities has been reported as a strong driver to working and getting committed to work at rural health facilities in Ghana and South Africa [38, 44]. Another reported asset was students’ ability to communicate in patients’ local language and their familiarity with local culture [23, 44]. As for students’ interests, these include a good on-site hospitality, the opportunity to spend time with their primary or extended families, the opportunity to explore rural areas and different clinical experience, and the opportunity for career advancement [24, 44].

In the particular context of Mali, marked by the overload of labour market in 1989, the government stopped recruiting HWs in urban areas [25]. This led young medical doctors facing unemployment challenges, to settle down in rural areas, with the encouragement of their university teachers and a Health NGO [25].

Barriers of the implementation of rural pipeline

Barriers to the implementation of the rural pipeline were documented by seven studies in this review [23, 28, 30, 31, 38, 42, 46]. Seven main barriers were identified to hamper implementation of the rural pipeline in sub-Saharan Africa. They include poor preparation of rural medical school candidates, tuition fees, scarcity of medical schools in rural areas, limited access to rural health facilities, inadequate rural living conditions, perceived inappropriate working conditions in rural health facilities, and perceived discrimination of rural HWs.

Poor preparation of rural health training schools’ candidates has been found to decrease likelihood for rural candidates to be selected for medical studies, as these candidates studied in inappropriate secondary schools [30, 42]. Indeed, studies from Tanzania, South Africa and Uganda reported that most rural secondary schools not only lack science teachers to prepare them for admission in medical schools [42], but also are ill-equipped in terms of laboratories, computers, Internet and libraries [24, 30, 42].

A study in Mali reported that tuition fees and complementary educational costs can represent a barrier to accessing medical school, especially for rural students [31]. According to this study, the tuition fees varied in 2017 from 320 000 in public schools to 450 000 CFA (1USD = 500 CFA) in private schools, excluding living expenses, which is more difficult for rural inhabitants to bear [31]. As a consequence, the majority of medical school candidates come from cities (urban areas) [31].

One of the barriers to implementing rural pipeline in sub-Saharan Africa is the scarcity of medical schools in rural areas. Amalba et al. reported in 2019 that Ghana’s medical schools are mainly concentrated in the cities and that the country faces challenges to extend medical care to smaller towns and rural areas [38]. Kapanda et al. mentioned similar reasons hampering establishment of medical schools in rural Tanzania, that is, poor rural infrastructures (lack of electricity, poor roads, poor communication services) and general poverty of rural populations [42].

Limited access to health facilities in rural areas has been said to harden rural medical practices in Mali and South Africa [30, 31]. In Mali, health facilities that are selected to receive students are generally the easy-to-reach ones [31]. As such, the long distance, coupled with the poor transport and inadequate roads affect mobility of students or HWs to reach rural health facilities as testified by graduates in South Africa [30].

Studies in Mali and Uganda have pointed out the inadequate living conditions of medical students and HWs in rural areas, as a key factor making the latter ones unwilling to work in rural areas [23, 31]. These conditions mainly include the lack of support for subsistence and appropriate accommodation. In Mali for instance, students from private school have to pay the travel cost and other livelihood expenses themselves in rural areas for their internship [31]. In Uganda, the lack of appropriate accommodation for married HWs, and tutor for young medical students has been reported to be key obstacles for maintaining health professionals in rural areas [24].

Perceived inappropriate working conditions in rural health facilities have been documented as a barrier to achieving the rural pipeline in South Africa, Malawi, Uganda and Ghana. Medical students and health workers have reported across these countries that health professionals working in rural areas are commonly exposed to demotivating working conditions such as exceeding workload, lack of time for holydays, poor health equipment and infrastructures and poor support supervision from the hierarchy [24, 28, 30, 46]. These conditions were said to affect HWs’ job satisfaction and well-being [24, 30].

Atuyambe et al. reported two aspects related to the discrimination of rural HWs, as reasons for low retention of medical graduates in rural areas [46]. The first one is the perceived limited opportunity for career progression, such as specialization or short-term courses for skills and competence updates, especially for long-term rural practice. The second one is the poorer remuneration of rural health workers as compared to urban HWs.

Discussion

This review contributes to complementing the existing literature regarding rural pipeline programmes implementation and their effects on rural health systems and communities in SSA. More specifically, it confirms the recommendations of updated WHO guideline on health workforce development, attraction, recruitment and retention in rural and remote areas from 2021 [4]. This scoping review indicates that a rural pipeline approach, as part of a bundle of broader interventions, contributes to retention of HWs in the SSA region. The scoping approach of the study did not allow assessment of the strength of the evidence for each rural pipeline pillar and strategy, hence now weight can be given to each of the recommendations below, in contrary to the WHO guidelines [4].

Rural pipeline strategies were reported to increase the number of rural health workers; to favour socio-economic well-being of health workers; to improve the quality of health services and access of rural community to healthcare; to reduce patient-provider communication barriers; to promote health education and promotion within rural communities; and to motivate communities to enrol their children in schools. Reviews on rural pipeline programmes have already been reported [51,52,53]. Holst et al. and Ogden et al. have shown that rural pipeline programmes have the potential to favour medical practice in rural and remote areas [51, 52]. Nevertheless, these reviews did not specify the potential of rural pipeline on improving the socio-economic development of health practitioners and rural communities access to quality health services. Another review conducted by MBemba et al. identified the effectiveness of rural pipeline programmes in improving health services utilizations [54]. However, this review did not stratify the effects of rural pipeline per pillar or strategy. Moreover, this review did not include studies from SSA. Our review fills in this gap by reporting on the effectiveness of the rural pipeline per pillar (Fig. 2).

This review pulls out the key implications for policy actions necessary to implementing rural pipeline programmes namely, ensuring that more rural students are selected into programs; developing curriculum for rural health training and delivery; and ensuring retention through educational and professional support. Strategies that prioritize rural students in selection processes were identified to increase health practitioner intention and willingness to work in rural areas and to reduce communication barriers between patients and healthcare providers. This strategy also contributes to socio-economic development of rural communities through the breaking of poverty cycle for rural students. Strategies that ensure curriculum development for rural health training and delivery were acknowledged to increase the availability of health workers in rural areas, improve quality of health services, favour health education and promotion within rural communities, and motivate communities for children’s schooling. Strategies that ensure rural retention through educational and professional support were reported to increase the number of health professional in rural areas and reinforces their social development—learn from community culture and lifestyle, and benefit for their hospitality. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that these findings might not be generalizable to all SSA region, as most of the papers included in this review were published from Southern and Eastern countries of Africa (Fig. 3). This disparity is more evident between French (Western and Central regions) and English-speaking (Eastern and Southern regions) countries of Africa. In fact, only 4 out of 22 (18%) of the published studies included in this scoping review were from Francophone countries.

Our finding adds to the understanding of implementation challenges of complex interventions such as rural pipeline. First, we assessed that only few studies reported the combination of two and more components of rural pipeline [29,30,31, 36, 41, 49]. None of the studies included in this review combined all the four components of the rural pipeline intervention. In addition, our study shows that the adoption of this program is very rarely the consequence of a governmental reform; which result into their insular implementation by actors, depending on their interests, powers or resources (Table 2). Moreover, the implementation of all these components of the rural pipeline, however, requires significant funding and long-term political commitment. Whereas in the context of low-income countries, such programmes are often supported by external funding and are of short duration. Indeed, of the studies that have indicated the context that led to the pipeline programme reforms, almost all were funded by external mechanisms (Table 2). For example, authors in DRC and Uganda reported that funding for rural pipeline programmes was supported by external development funds, and over a period of 2–3 years [29, 43, 46]. In Mali, an international NGO was reported to support health professionals who settle in rural areas through the provision of better living conditions (water, solar panels, motorbike) and working conditions (basic equipment, continuous education, peer support and mentoring) [26]. Such external financial support can serve as a catalyst mechanism to sustain the implementation of health workforce development programmes. This means that, at local levels, prerequisites should exist in terms of infrastructures and equipment of health training institutions and health facilities, for such funding to contribute to an effective implementation of the health workforce development programme. Nevertheless, our study revealed a lack of adequate (primary and secondary) schooling and health facility infrastructures and equipment in some rural and underserved settings where pipeline programmes were implemented. Meeting such prerequisite would allow local recruitment and training of students into rural pipeline programmes, and favour future sustainable uptake of jobs in these locations. We also analysed that the achievement of rural pipeline programmes also relies on accompanying measures for the human resources at operational level such as students, local medical school lecturers, supervisors of students at health facility level. These measures may include appropriate housing; scholarship for students to remove the barrier of training costs but also for their subsistence; incentives for the rural supervision health workers; adequate wage for rural HWs and other amenities for good living conditions of the lecturers generally coming from cities such as electricity, roads to easily access cities, communication (phone network, internet), appropriate markets. These findings raise calls for the prioritization of interconnected interventions, tailored with specific country contexts and with full commitment of government and (intern) national stakeholders for investing in the health sector to address health workforce placement related challenges. It also entails encouraging inter-sectoral collaborations in the implementation of health workforce strategies for an improved feasibility (through the meeting of prerequisites such as appropriate living and working conditions for the health workforce) and sustainability of its impacts on local health systems and services.

Another finding that calls for policy considerations is the limited attention given to the allied health professions (nurses, midwives) in the implementation of the rural pipeline. Only five of the articles included in this study reported on rural pipeline programmes targeting nursing and midwifery learners [23, 24, 28, 29, 31]. However, this result contrasts with the socio-economic realities of low-income countries such as those in SSA. Indeed, medical training requires more time, human resources (teachers) and financial resources (training and equipment costs) than nursing and midwifery trainings. Also, retaining medical doctors in rural areas appears to be more difficult and costly than other professional categories [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. However, nurses and midwives constitute the bulk of maternal and child health care providers [63]. Therefore, investing in the development of auxiliary health workers such as nurses and midwives is likely cost-effective in the African context and would lead to faster results in improving health workforce availability and health indicators rural communities.

This review has identified an additional pillar to the already documented pillars [10]. This relates to social accountability; that is ensuring that students will meet community health needs after graduation. It builds on strategies such as matching students’ socio-demographic profiles to the communities and ensuring they remain in communities they are assigned to, after their placement. We consider this pillar a key asset of the rural pipeline programme as it is a favourable outcome based on the other pillars such as promoting rural recruitment of students, supporting their training through scholarships, creating adequate conditions for training and internship in rural areas, exposing them to the rural realities of care during training.

Limitations

The present review has some limitations. First, the methodological design of this study—scoping review—did not allow any quality assessment of included studies. Moreover, given that only two researchers checked and agreed on the database, there might be a risk of selection bias. This could limit the internal validity of the effectiveness of rural pipeline interventions reported in the present study. A meta-analysis study design could overcome this but given the criteria needed for inclusion in such a review, it is likely that very few articles would be included. Second, the geographical disparity of selected studies, with most studies published from Eastern and Southern regions could undermine the generalization of findings to the whole SSA. This could also hamper the external validity of the findings to other low-income countries. We argue for future studies to include an explorative case-study design for specific countries as this would provide for more contextual and robust evidence on the effectiveness, and eventual impact, of the rural pipeline implementation.

Conclusion

This scoping review shows that rural pipeline programmes potentially impact rural health systems and services by increasing the number of rural health practitioners; reducing communication barriers between healthcare providers and community members; changing household economic and social circumstances especially for students from poor family; and improving the quality of health services. However, rural pipeline can result in some unintended impacts such as perceived workload increased by trainee’s supervisors; increased job absenteeism among senior health providers; discomfort of being attended by students; and perceived poor quality care provided by students. Additionally, poor preparation of rural health training schools’ candidates; tuition fees payment; limited access to rural health facilities for students training; inadequate living and working conditions; and perceived discrimination of rural health workers hamper the effective implementation of rural pipeline approach in sub-Saharan Africa. We recommend interconnecting interventions and tailoring them with country specific contexts to address rural health workforce development related challenges hereby improving rural pipeline programmes implementation and their impact in rural sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, there is a need to undertake more health workforce development interventions targeting nursing and midwifery professions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, we call for more governmental commitment for improving rural living, and working environments to facilitate the implementation of rural health workforce development programmes.

References

Boniol M, Kunjumen T, Nair TS, Siyam A, Campbell J, Diallo K. The global health workforce stock and distribution in 2020 and 2030: a threat to equity and ‘universal’ health coverage? BMJ Glob Heal. 2022;7(6):e009316. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJGH-2022-009316.

World Health Organization. Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. Hum Resour Heal Obs Ser. 2016;(17):1-40. ISBN 978 92 4 151140 7.

Butler C. A World at Risk: Annual Report on Global Preparedness for Health Emergencies Global Preparedness Monitoring Board. vol. 151; 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/40153772.

Dussault G, Franceschini MC. Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-4-12.

WHO. WHO guideline on health workforce development, attraction, recruitment and retention in rural and remote areas. 2021:6.

World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health. Geneva: Switzerland; 2006.

High level commission on health employment and economic growth. Working for Health and Growth: Investing in the health workforce. WHO Libr Cat Data. 2016:78–80. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511308. Accessed 26 Oct 2021.

World Health Organization, International Labour Organization O for ED and C. Working for Health: A Review of the Relevance and Effectiveness of the Five-Year Action Plan for Health Employment and Inclusive Economic Growth (2017–2021) and ILO-OECD-WHO Working for Health Programme.; 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/340716. Accessed 26 Oct 2021.

World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. WHO. 2016:64. http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/media/news/2014/consultation_globstrat_hrh/en/%0A. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250368/1/9789241511131-eng.pdf?ua=1%5Cn. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/pub_globstrathrh-2030/en/.

Tesson G, Curran V, Pong R, Strasser R. Advances in rural medical education in three countries: Canada, the United States and Australia. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2005;18(3):405–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576280500289728.

Greenhill JA, Walker J, Playford D. Outcomes of Australian rural clinical schools: a decade of success building the rural medical workforce through the education and training continuum. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(3):1–14. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH2991.

Phillips JP, Wendling AL, Bentley A, Marsee R, Morley CP. Trends in US medical school contributions to the family physician workforce: 2018 update from the American academy of family physicians. Fam Med. 2019;51(3):241–50. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.395617.

Lee YH, Barnard A, Owen C. Initial evaluation of rural programs at the Australian National University: understanding the effects of rural programs on intentions for rural and remote medical practice. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11(2). https://doi.org/10.22605/rrh1602.

Longenecker RL, Andrilla CHA, Jopson AD, et al. Pipelines to pathways: medical school commitment to producing a rural workforce. J Rural Health. 2021;37(4):723–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/JRH.12542.

Wheat JR, Leeper JD. Pipeline programs can support reforms in medical education: a cohort study of Alabama’s rural health leaders pipeline to engage community leaders. J Rural Heal. 2021;37(4):745. https://doi.org/10.1111/JRH.12531.

Rourke J, Asghari S, Hurley O, et al. From pipelines to pathways: the memorial experience in educating doctors for rural generalist practice. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(1). https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH4427.

Carson DB, Schoo A, Berggren P. The, “rural pipeline” and retention of rural health professionals in Europe’s northern peripheries. Health Policy. 2015;119(12):1550–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HEALTHPOL.2015.08.001.

Winn CS, Chisholm BA, Hummelbrunner JA, Tryssenaar J, Kandler LS. Impact of the Northern Studies Stream and Rehabilitation Studies Programs on Recruitment and Retention To Rural and Remote Practice: 2002–2010. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(2):1–13. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH3126.

Taylor J, Goletz S. From pipeline to practice: utilizing tracking mechanisms for longitudinal evaluation of physician recruitment across the health workforce continuum. Eval Program Plann. 2021;89. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EVALPROGPLAN.2021.102014.

Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Hazelwood CE. A program to increase the number of family physicians in rural and underserved areas: impact after 22 years. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;281(3):255–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.3.255.

Carson DB, Schoo A, Berggren P. The, “rural pipeline” and retention of rural health professionals in Europe’s northern peripheries. Health Policy (New York). 2015;119(12):1550–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.08.001.

Reid SJ, Peacocke J, Kornik S, Wolvaardt G. Compulsory community service for doctors in South Africa: a 15-year review. South African Med J. 2018;108(9):741–7. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i9.13070.

Dan K Kaye, Andrew Mwanika NS. Influence of the training experience of Makerere University medical and nursing graduates on willingness and competence to work in rural health facilities|Rural and Remote Health. Rural Remote Health. https://doi.org/10.3316/INFORMIT.326747802610247. Published 2010. Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Kaye DK, Mwanika A, Sekimpi P, Tugumisirize J, Sewankambo N. Perceptions of newly admitted undergraduate medical students on experiential training on community placements and working in rural areas of Uganda. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-10-47/TABLES/4.

Coulibaly S, Desplat D, Kone Y, et al. Une médecine rurale de proximité: l’expérience des médecins de campagne au Mali. Educ Health. 2007;20(2):47.

Van Dormael M, Dugas S, Kone Y, et al. Appropriate training and retention of community doctors in rural areas: a case study from Mali. Hum Resour Health. 2008;6(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-6-25/TABLES/3.

Dormael M Van, Dugas S, Kone Y, et al. Human resources for health appropriate training and retention of community doctors in rural areas: a case study from Mali. 2008;8:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-6-25.

Schmiedeknecht K, Perera M, Schell E, Jere J, Geoffroy E, Rankin S. Predictors of workforce retention among Malawian nurse graduates of a scholarship program: a mixed-methods study. Glob Heal Sci Pract. 2015;3(1):85–96. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00170.

Michaels-Strasser S, Thurman PW, Kasongo NM, et al. Increasing nursing student interest in rural healthcare: lessons from a rural rotation program in Democratic Republic of the Congo. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12960-021-00598-9/FIGURES/4.

Gumede DM, Taylor M, Kvalsvig JD. Engaging future healthcare professionals for rural health services in South Africa: students, graduates and managers perceptions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12913-021-06178-W/FIGURES/3.

Sidibé CS, Touré O, Broerse JEW, Dieleman M. Rural pipeline and willingness to work in rural areas: mixed method study on students in midwifery and obstetric nursing in Mali. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0222266. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0222266.

Sirili N, Simba D. It is beyond remuneration: bottom-up health workers’ retention strategies at the primary health care system in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0246262. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0246262.

Marjolein D, Hillhorst T. Governance and human resources for health. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:29.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Scoping Reviews Manual. https://jbi.global/scoping-review-network/resources. Published 2021. Accessed 11 Aug 2021.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. 2018;169(7):467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Amalba A, Van Mook WNKA, Mogre V, Scherpbier AJJA. The perceived usefulness of community based education and service (COBES) regarding students’ rural workplace choices. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-016-0650-0/FIGURES/1.

Amalba A, Van Mook WNKA, Mogre V, Scherpbier AJJA. The effect of Community Based Education and Service (COBES) on medical graduates’ choice of specialty and willingness to work in rural communities in Ghana. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-016-0602-8/TABLES/2.

Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJJA, van Mook WNKA. Trainees’ preferences regarding choice of place of work after completing medical training in traditional or problem-based learning/community-based education and service curricula: a study in Ghanaian medical schools. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(3):5087–5087. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5087.

Hatcher AM, Onah M, Kornik S, Peacocke J, Reid S. Placement, support, and retention of health professionals: national, cross-sectional findings from medical and dental community service officers in South Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-12-14.

Clithero-Eridon A, Crandall C, Ross A. Future medical student practice intentions: the South Africa experience. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-020-02361-5/TABLES/3.

McGregor RG, Ross AJ, Zihindula G. The socioeconomic impact of rural-origin graduates working as healthcare professionals in South Africa. South Africa Family Pract. 2019;61(5):184–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2019.1647006.

Kapanda GE, Muiruri C, Kulanga AT, et al. Enhancing future acceptance of rural placement in Tanzania through peripheral hospital rotations for medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-016-0582-8/TABLES/4.

Kizito S, Baingana R, Mugagga K, Akera P, Sewankambo NK. Influence of community-based education on undergraduate health professions students’ decision to work in underserved areas in Uganda. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13104-017-3064-0/TABLES/6.

Mapukata NO, Dube R, Couper I, Mlambo MG. Factors influencing choice of site for rural clinical placements by final year medical students in a South African university. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2017;9(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/PHCFM.V9I1.1226.

Arscott-Mills T, Kebaabetswe P, Tawana G, et al. Rural exposure during medical education and student preference for future practice location—a case of Botswana. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2016;8(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/PHCFM.V8I1.1039.

Atuyambe LM, Baingana RK, Kibira SPS, et al. Undergraduate students’ contributions to health service delivery through community-based education: a qualitative study by the MESAU Consortium in Uganda. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-016-0626-0/FIGURES/2.

Van Schalkwyk S, Blitz J, Couper I, et al. Consequences, conditions and caveats: a qualitative exploration of the influence of undergraduate health professions students at distributed clinical training sites. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-018-1412-Y/TABLES/2.

Ratie Mpofu, Priscilla S Daniels, Tracy-Ann Adonis WMK. Impact of an interprofessional education program on developing skilled graduates well-equipped to practise in rural and underserved areas|Rural and Remote Health. Rural Remote Health. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.451122885758732. Published 2014. Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Couper ID, Hugo JFM, Conradie H, Mfenyana K. Influences on the choice of health professionals to practise in rural areas. South African Med J. 2007;97(11):1082–6.

Assefa T, Haile Mariam D, Mekonnen W, Derbew M. Medical students’ career choices, preference for placement, and attitudes towards the role of medical instruction in Ethiopia. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-017-0934-Z/TABLES/3.

Ogden J, Preston S, Partanen RL, Ostini R, Coxeter P. Recruiting and retaining general practitioners in rural practice: systematic review and meta-analysis of rural pipeline effects. Med J Aust. 2020;213(5):228–36. https://doi.org/10.5694/MJA2.50697.

Holst J. Increasing rural recruitment and retention through rural exposure during undergraduate training: an integrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH17176423.

O’Sullivan BG, McGrail MR, Russell D, Chambers H, Major L. A review of characteristics and outcomes of Australia’s undergraduate medical education rural immersion programs. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0271-2

Mbemba G, Gagnon MP, Paré G, Côté J. Interventions for supporting nurse retention in rural and remote areas: an umbrella review. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-44/TABLES/2.

Rockers PC, Jaskiewicz W, Wurts L, et al. Preferences for working in rural clinics among trainee health professionals in Uganda: a discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-212

Prust ML, Kamanga A, Ngosa L, et al. Assessment of interventions to attract and retain health workers in rural Zambia: a discrete choice experiment. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-019-0359-3

Miranda JJ, Diez-Canseco F, Lema C, et al. Stated preferences of doctors for choosing a job in rural areas of Peru: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2012;7(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050567

Takemura T, Kielmann K, Blaauw D. Job preferences among clinical officers in public sector facilities in rural Kenya: A discrete choice experiment. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-015-0097-0

Mumbauer A, Strauss M, George G, et al. Employment preferences of healthcare workers in South Africa: Findings from a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2021;16(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0250652

Honda A, Vio F. Incentives for non-physician health professionals to work in the rural and remote areas of Mozambique-a discrete choice experiment for eliciting job preferences. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-015-0015-5

Russell D, Mathew S, Fitts M, et al. Interventions for health workforce retention in rural and remote areas: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00643-7.

Witter S, Herbst CH, Smitz M, Balde MD, Magazi I, Zaman RU. How to attract and retain health workers in rural areas of a fragile state: findings from a labour market survey in Guinea. PLoS One. 2021;16(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0245569

WHO WHO. Global strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery 2016–2020. 2016:1–13. https://www.who.int/hrh/nursing_midwifery/nursing-midwifery/en/.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Abdou Illou Mourtalla and Michelle Mcisaac for their inputs in the paper.

Funding

This study is financed by the Health Workforce Department of the WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study protocol was developed by DK and reviewed by RvdP, LC and PZ. Literature search, screening and selection of articles were performed by DK and RvdP. DK and RvdP did the data analysis and all authors were involved. The first draft of the manuscript was written by DK and critically reviewed by RvdP, LC and PZ. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a review of published articles. It therefore does not require ethics approval or consent from participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All materials used in this study may be available upon request to LC at: codjial@who.int.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolié, D., Van De Pas, R., Codjia, L. et al. Increasing the availability of health workers in rural sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review of rural pipeline programmes. Hum Resour Health 21, 20 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-023-00801-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-023-00801-z