Abstract

Context

A higher incidence of thromboembolic disorders in COVID-19 has been reported by many clinicians worldwide.

Objective, design and data sources

Selected studies found in PubMed that reported thromboembolic events were included for meta-analysis using weighted fixed and random effects. Data from 19 articles on cohort studies in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and thromboembolic events, including thrombosis and embolism were included in this review.

Results

The likelihood for developing thromboembolic disorders in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was 0.28 (95% CI 0.21–0.36).

Conclusion

This study further validates the increased risk of VTE in COVID-19 patients when compared to healthy, non-hospitalized people, and hospitalized patients. These findings will be useful to researchers and medical practitioners caring for COVID-19 patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Some viral infections manifest clinically with hemorrhage and coagulation syndromes. These may run the spectrum of mild skin hemorrhages to disseminated intravascular coagulation. Dengue, endemic in the Caribbean and in Asia, may present as skin rashes and petechiae in its mild form, but may be also associated with hemorrhagic shock syndromes in severe cases. Viral hemorrhagic fevers, like Ebola, Marburg, Lassa fever, Rift Valley fever and Crimean Congo fever, named after geographic locations where they were first discovered or are most prevalent, trigger hemorrhages of varying degrees of severity, some associated with high morbidity and mortality. Some patients with cytomegalovirus and parvovirus B19 may develop clotting abnormalities, like thrombosis. Viral respiratory tract infections are known to increase the risk of deep venous thrombosis and possibly pulmonary embolism [1].

Reports on coronaviruses did not appear in the literature until the 1960’s. Early documented cases of coronaviruses (HcoV-OC43, HcoV-NL63, HcoV-229E, and HKU1) were reported to produce only mild upper respiratory infections in immunocompromised patients. In 2003, the sudden appearance of the highly pathogenic Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) in Asia spread to more than two dozen countries worldwide before disappearing in mid-2003. SARS was followed in 2012 by another highly pathogenic coronavirus, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV) [2,3,4,5]. MERS, a zoonotic disease which spread mostly among Middle East countries including Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Qatar, Oman, Kuwait, and UAE, eventually reached Europe. Smaller outbreaks have occurred subsequently among healthcare workers, but it has been generally contained. Patients with severe MERS developed pneumonia and kidney failure with about 35% of patients dying of the disease [6]. The multi-country epidemics of SARS and MERS were associated with coagulation disorders. Severe SARS patients developed thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) [7, 8], while MERS was associated with intracerebral hemorrhage and DIC [9, 10].

SARS-CoV-2, the etiologic agent of COVID-19, is a highly infectious coronavirus responsible for the current global pandemic. As of March 29, 2021, it has claimed more than 2.7 million lives and infected 127 million people globally since it was first reported in December 2019 [11]. Although the mortality rate is lower than MERS or SARS, it is more infectious and highly contagious [12]. Vascular complications, such as stroke, thrombosis, and embolism, have accounted for many of the fatalities. COVID-19 infection has also been associated with hypercoagulability with development of ischemic changes, including gangrene of fingers and toes. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy was found in Chinese patients [13].

Several factors lead to the hypercoagulability state in patients with severe cases of COVID-19: circulatory stasis from immobility (common to intensive care patients), acute inflammatory reaction overdrive with increases in acute phase proteins (e.g., fibrinogen, c-reactive protein) and elevated clotting factors, increased Von Willebrand Factor (vWF) activity, neutrophilia, and increase in Neutrophil Extracellular traps (NETs) [14]. Reports have also shown possible direct endothelial injury [15, 16] and increased blood viscosity in COVID-19 patients that may further result in thrombogenesis [17]. In addition, the hypoxia found in severe COVID-19 can stimulate thrombosis not only by increasing blood viscosity, but also a hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-dependent signaling pathway [18]. Large-vessel stroke has been reported as a potential early presentation of COVID-19 patients [19]. All the elements of Virchow’s triad - hypercoagulability, stasis, and endothelial injury and dysfunction - can present in COVID-19 patients.

Several reports of the thromboembolic consequences of COVID-19 have recently been published. The aim of this study is to determine the incidence of thromboembolic events in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Methods

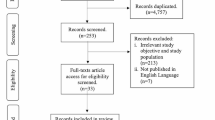

This study followed PRISMA guidelines for conducting meta-analysis [20]. PubMed searches were performed from July 6 to July 8, 2020 for articles published between January 1, 2020 and July 1, 2020. Searches were limited to PubMed because of the unprecedented increase in COVID-19 publications (already more than 35,000 publications from January 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020). Using the search terms, “COVID-19 AND Thrombosis”, 396 articles were found, while the search for “COVID-19 AND Embolism” found 207 articles. Duplicate publications were deleted, and only independent research articles were included in the review. Letters, commentaries, opinions, perspectives and review articles, including systematic reviews and meta-analysis were excluded. However, research letters that included patient cohorts were included. Of the 62 articles found, 19 articles that had data on cohort studies in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and vascular findings, including thrombosis, embolism, and endothelial injury, were included in this meta-analysis. The search strategy is summarized in Fig. 1. Table 1 lists the 19 selected studies with relevant information on period of study, mean age, sex, venous thromboembolic (VTE) effects and clinical outcomes for each study.

Table 1 shows the Attributes of the 19 Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis.

Data were analyzed using StatDirect 3 (StatsDirect Ltd) and Rstudio, Version 1.2.5033 (RStudio, Inc). Proportions were transformed using the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine method [40] and were combined separately using an inverse-variance weighted fixed method and random effect method (DerSimonian-Laird estimator for Tau2) [41] and by the Jackson method for confidence interval of Tau2 and Tau [42]. While the inverse-variance weighted fixed method does not account variation across 19 studies, the random effect method does. Visualization for bias detection and assessment was plotted. Bias testing was performed using Begg-Mazumdar, Harbord and Egger tests.

Results

The total pooled COVID-19 patient population was 2554. The forest plot of results of the analysis in Fig. 2 shows the likelihood (95% CIs) of thromboembolic events in this COVID-19 population. The pooled incidence rate of development of thromboembolic disorder was 0.28 (95% CI 0.21–0.36). Egger test with a P-value of 0.014 illustrates further significant publication bias. A P-value less than 0.05 implies publication bias [43, 44].

Pooled proportion of VTE using the fixed effect method was 0.22, but the heterogeneity measure of studies (I2) was large, 93.6% (95% CI 91.3–95.3%). A random effects analysis was used instead to generate the forest plot which gave an inverse variance value of 0.28 (95% CI 0.21–0.36). The pooled estimates of the odds ratios from the random effect meta-regression analyses for effect of four variables of interest on developing VTE (age, thromboprophylaxis, ICU admission and sex) were not significant.

Discussion

Earlier reports have shown increased incidence of thromboembolic events in COVID-19 patients that is confirmed by this meta-analysis. The pooled incidence rate from the analysis of 19 studies indicates that about 28% (95% CI 21–36%) of COVID-19 patients will develop venous thromboembolic events, a higher incidence than in the general population, hospitalized ICU and non-ICU patients. Two reports of cohort studies [28, 29] that included patient controls showed lower incidence of VTE in the control population, 5 and 10%, respectively, much lower than 28% found in COVID-19 patients in this review. In a study among county residents, Heit et al. [45] found that the average annual incidence (adjusted by age and sex) of in-hospital VTE was 960.5 (95% CI, 795.1–1125.9) per 10,000. The incidence among non-hospitalized community residents was 7.1 (95% CI, 6.5–7.6) per 10,000 person-years or 100 times lower [45]. Among ICU patients, the cumulative incidence of VTE at 28 days, determined by weekly intervals was 4.45% (95% CI 2.55–7.71) [46].

Hospitalization increases the risk for VTE. In a review based on the 2003 Nationwide Inpatient Sample from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) showed the risk for developing VTE among surgical patients classified as low, moderate, high, and very high were 44, 15, 24, and 17% respectively [47]. Among medical patients, 51% (7.7 million) fit the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) VTE risk criteria. Even after discharged from the hospital, 31% (12 million) patients continued to be at risk of VTE overall [47]. However, evidence seems to implicate infections with the SARS-CoV-2 with thromboembolic complications more than just hospitalization. In a study by Helms et al. that compared 145 non-COVID-19 ARDS patients with 77 COVID-19 ARDS patients [30], they found that COVID-19 patients developed significantly more thromboembolic complications, mainly pulmonary embolisms (11.7 vs. 2.1%, p < 0.008). Another study by Poissy et al. [48], compared 107 ICU COVID-19 patients with historical controls of influenza patients admitted to the same ICU in the previous year, and to another group of patients hospitalized with influenza. Their analysis showed more COVID-19 patients developed PE (20.6%), in contrast to PE rates of 6.1 and 7.5%, in the general ICU population and the influenza population, respectively [48].

ICU patients are predisposed to developing thromboembolism from all elements of Virchow’s triad. Two more papers in this review provide evidence that ICU patients with COVID-19 are at greater risk to VTE. Lodigiani, et al. reported that in 388 COVID-19 patients, thromboembolic events occurred in 27.6% of ICU patients but only 6.6% general ward patients [28]. In another study by Middeldorp et al. comparing 75 ICU and 123 ward patients with COVID-19, VTE occurred in 47% (35/75) of ICU patients [27]. Asymptomatic VTE was diagnosed in only 3% of ward patients [27]. A meta-regression of the entire study showed that ICU patients are 104% more likely to develop VTE although this was not significant (p = 0.165). Ward patients, who are likely to ambulate more, might be less prone to develop VTE.

Several societies and organizations have advanced recommendations, guidelines, and consensus statements regarding anticoagulation and COVID-19 patients. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) suggests using prophylactic-intensity over intermediate-intensity or therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation for patients with COVID-19–related critical illness who do not have suspected or confirmed VTE [49]. The American College of Cardiology also recommends that all patients hospitalized with COVID-19 receive pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis unless a specific contraindication (such as active bleeding) exists [50]. The NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines states that “there are currently insufficient data to recommend either for or against the use of thrombolytics or higher than the prophylactic dose of anticoagulation for VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized COVID-19 patients outside of a clinical trial.” [51].

The entire population of 2554 patients were considered as a cohort of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and the individual study effects of anticoagulation or specific anticoagulant use was not accounted for except to note that the majority of patients in this study (93.5%) were given some type of anticoagulant, variously described as prophylactic, intermediate, or therapeutic. Each study was weighted to account for its number of patients.

The differences between studies were large with a 94% I2 inconsistency value, therefore, a random effects model with pooled proportion (=0.28) was adopted to account for the heterogeneity of the 19 studies reviewed. Also, between-study heterogeneity was large, and tests of bias were statistically significant indicating a “small sample” bias across the 19 studies.

In order to explore the association between patient characteristics and VTE development, a meta-regression was used. Since a fixed effects meta-regression model does not account for high heterogeneity across different studies, a random-effect meta-regression analysis was adopted although the meta-regression results for the effects of age, gender, thromboprophylaxis and ICU admission did not attain statistical significance. Possible intercorrelation between thromboprophylaxis and other variables could exist - not controlling for such intercorrelations could yield misleading information. For example, patients given thromboprophylaxis might have greater medical burdens that those without and thus they are more vulnerable to VTE.

Limitations

The literature search was limited only to PubMed because of the unprecedented increase in COVID-19 publications. The 19 studies reviewed came from several countries and were very heterogeneous. Additionally, the effects of international variations in patient populations, testing strategies, thrombosis prophylactic measures, diagnostic test quality and availability, access to care and treatment strategies, as well as variability in outcome reporting for COVID-19, might also be a limitation. However, the adoption of the random effect approach instead of fixed effect approach might compensate for the diversity. These issues influence the reported diagnosed cases, casualties, and, in turn case-fatality rates. The incidence reported in this study might change as more cohort studies are reported and clinicians learn more about COVID-19 and its management. Publication bias brought about by publications analyzed in this review depend on a large extent on what their authors might consider as significant or perceive as important - these factors are beyond the control of this review. This study may have failed to include all relevant studies which might affect the estimated incidence. With COVID-19 now a worldwide pandemic, non-English publications may have also been missed (language bias). The large heterogeneity (I2 = 94%) also indicates a sample bias.

Conclusion

This study provides more evidence that COVID-19 increases the risk of VTE. Although the majority of the reports did not have a control group, a comparison with historical groups of patients in the general community, hospitalized patients, and ICU patients showed a significant difference between the incidence of thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients. Vulnerable patients, such as the elderly, and those with other chronic comorbid conditions have greater risk of hospitalizations and, even critical care unit admissions, which will further predispose them to even greater risk of thromboembolism. The current consensus among experts supports anticoagulation in all hospitalized COVID-19 patients who have moderate to severe disease and in critically ill patients [52]. The findings of this study might be potentially useful to medical practitioners who care for COVID-19 patients who are at higher risk of developing thromboembolic events.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- VTE:

-

Venous thromboembolism

- ARDS:

-

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

References

Smeeth L, Cook C, Thomas S, Hall A, Hubbard R, Vallance P. Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after acute infection in a community setting. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1075–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68474-2.

Cui J, Li F, Shi Z. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;17(3):181–92.

Li J, You Z, Wang Q, Zhou Z, Qiu Y, Luo R, et al. The epidemic of 2019-novel-coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia and insights for emerging infectious diseases in the future. Microbes Infect. 2020;22(2):80–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.002.

Kahn J, McIntosh K. History and recent advances in coronavirus discovery. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(11):S223–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000188166.17324.60.

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017.

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Who.int. 2021 [cited 12 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-(mers-cov).

Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, Joynt G, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1986–94. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa030685.

Singh S. Middle East respiratory syndrome virus pathogenesis. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2016;37(04):572–7.

van den Brand J, Smits S, Haagmans B. Pathogenesis of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Pathol. 2014;235(2):175–84.

Li T, Lu H, Zhang W. Clinical observation and management of COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):687–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1741327.

ArcGIS Dashboards [Internet]. Gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com. 2021 [cited 29 March 2021]. Available from: https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

Petrosillo N, Viceconte G, Ergonul O, Ippolito G, Petersen E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: are they closely related? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(6):729–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.026.

Jin S, Jin Y, Xu B, Hong J, Yang X. Prevalence and impact of coagulation dysfunction in COVID-19 in China: a meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(11):1524–35. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1714369.

Barnes B, Adrover J, Baxter-Stoltzfus A, Borczuk A, Cools-Lartigue J, Crawford J, et al. Targeting potential drivers of COVID-19: Neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2020;217(6):e20200652.

Ackermann M, Verleden S, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary vascular Endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2015432.

Cao W, Li T. COVID-19: towards understanding of pathogenesis. Cell Res. 2020;30(5):367–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-0327-4.

Gertz M, Kyle R. Hyperviscosity syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 1995;10(3):128–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/088506669501000304.

Gupta N, Zhao Y, Evans C. The stimulation of thrombosis by hypoxia. Thromb Res. 2019;181:77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2019.07.013.

Oxley T, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner C, Shoirah H, Singh I, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):e60. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2009787.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Stoneham S, Milne K, Nuttall E, Frew G, Sturrock B, Sivaloganathan H, et al. Thrombotic risk in COVID-19: a case series and case–control study. Clin Med. 2020;20(4):e76–81. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0228.

Zhang L, Feng X, Zhang D, Jiang C, Mei H, Wang J, et al. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Circulation. 2020;142(2):114–28. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046702.

Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14830.

Klok F, Kruip M, van der Meer N, Arbous M, Gommers D, Kant K, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041.

Demelo-Rodríguez P, Cervilla-Muñoz E, Ordieres-Ortega L, Parra-Virto A, Toledano-Macías M, Toledo-Samaniego N, et al. Incidence of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and elevated D-dimer levels. Thromb Res. 2020;192:23–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.018.

Pavoni V, Gianesello L, Pazzi M, Stera C, Meconi T, Frigieri F. Evaluation of coagulation function by rotation thromboelastometry in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(2):281–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02130-7.

Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps T, Foppen M, Vlaar A, Müller M. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Vascular Surg. 2021;9(2):536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.12.004.

Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M, Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thrombosis Res. 2020;191:9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024.

Llitjos J, Leclerc M, Chochois C, Monsallier J, Ramakers M, Auvray M, et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1743–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14869.

Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x.

Koleilat I, Galen B, Choinski K, Hatch A, Jones D, Billett H, et al. Clinical characteristics of acute lower extremity deep venous thrombosis diagnosed by duplex in patients hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019. J Vasc Surg. 2021;9(1):36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.06.012.

Zerwes S, Hernandez Cancino F, Liebetrau D, Gosslau Y, Warm T, Märkl B, et al. Erhöhtes Risiko für tiefe Beinvenenthrombosen bei Intensivpatienten mit CoViD-19-Infektion? – Erste Daten. Chirurg. 2020;91(7):588–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-020-01222-7.

Thomas W, Varley J, Johnston A, Symington E, Robinson M, Sheares K, et al. Thrombotic complications of patients admitted to intensive care with COVID-19 at a teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Thromb Res. 2020;191:76–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.028.

Nahum J, Morichau-Beauchant T, Daviaud F, Echegut P, Fichet J, Maillet J, et al. Venous thrombosis among critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e2010478. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10478.

Longchamp A, Longchamp J, Manzocchi-Besson S, Whiting L, Haller C, Jeanneret S, et al. Venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with COVID-19: results of a screening study for deep vein thrombosis. Res Pract Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2020;4(5):842–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/rth2.12376.

Gervaise A, Bouzad C, Peroux E, Helissey C. Acute pulmonary embolism in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients referred to CTPA by emergency department. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(11):6170–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-06977-5.

Mestre-Gómez B, Lorente-Ramos R, Rogado J, Franco-Moreno A, Obispo B, Salazar-Chiriboga D, et al. Incidence of pulmonary embolism in non-critically ill COVID-19 patients. Predicting factors for a challenging diagnosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;51(1):40–6.

Inciardi R, Adamo M, Lupi L, Cani D, Di Pasquale M, Tomasoni D, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in northern Italy. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1821–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa388.

Soumagne T, Lascarrou J, Hraiech S, Horlait G, Higny J, d’Hondt A, et al. Factors associated with pulmonary embolism among coronavirus disease 2019 acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicenter study among 375 patients. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(7):e0166. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000000166.

Freeman M, Tukey J. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21(4):607–11. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729756.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Jackson D. Confidence intervals for the between-study variance in random effects meta-analysis using generalised Cochran heterogeneity statistics. Res Synth Methods. 2013;4(3):220–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1081.

Sedgwick P. Meta-analyses: how to read a funnel plot. BMJ. 2013;346(mar01 2):f1342.

Zhang L, Gerson L, Maluf-Filho F. Systematic review and meta-analysis in GI endoscopy: why do we need them? How can we read them? Should we trust them? Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(1):139–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2018.03.001.

Heit J, Melton L, Lohse C, Petterson T, Silverstein M, Mohr D, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients vs community residents. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(11):1102–10. https://doi.org/10.4065/76.11.1102.

Zhang C, Zhang Z, Mi J, Wang X, Zou Y, Chen X, et al. The cumulative venous thromboembolism incidence and risk factors in intensive care patients receiving the guideline-recommended thromboprophylaxis. Medicine. 2019;98(23):e15833. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015833.

Anderson F, Zayaruzny M, Heit J, Fidan D, Cohen A. Estimated annual numbers of US acute-care hospital patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Am J Hematol. 2007;82(9):777–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.20983.

Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, Parmentier E, Duburcq T, Lassalle F, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;142(2):184–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430.

Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, Angchaisuksiri P, Blair C, Dane K, et al. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5(3):872–88. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003763.

Feature | Thrombosis and COVID-19: FAQs For Current Practice - American College of Cardiology. American College of Cardiology. 2021 [cited 2 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/04/17/14/42/thrombosis-and-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-faqs-for-current-practice

Information on COVID-19 Treatment, Prevention and Research. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. 2021 [cited 2 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/antithrombotic-therapy/.

Chandra A, Chakraborty U, Ghosh S, Dasgupta S. Anticoagulation in COVID-19: current concepts and controversies. Postgrad Med J. 2021:postgradmedj-2021-139923. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-139923.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Library of Medicine (NLM) and Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications (LHNCBC). We thank Dr. Craig Locatis for discussions, critical reviews, and editing the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PF conceived of the study and study design, reviewed the PubMed search results, participated in data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MB assisted in the study design, assisted in the data analysis, and in drafting the manuscript. ZZ and SB analyzed the data, created the forest plot and assisted in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fontelo, P., Bastola, M.M., Zheng, Z. et al. A review of thromboembolic events in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Thrombosis J 19, 47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-021-00298-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-021-00298-3