Abstract

Research question

To evaluate the role of endometrial scratching performed prior to an embryo transfer cycle on the probability of pregnancy compared to placebo/sham or no intervention.

Design

A computerized literature (using a specific search strategy) search was performed across the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, COCHRANE CENTRAL, SCOPUS and WEB OF SCIENCE up to June 2023 in order to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effect of endometrial scratching prior to an embryo transfer cycle on the probability of pregnancy, expressed either as live birth, ongoing pregnancy or clinical pregnancy (in order of significance) compared to placebo/sham or no intervention. Data were pooled using random-effects or fixed-effects model, depending on the presence or not of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. Subgroup analyses were performed based on the population studied in each RCT, as well as on the timing and method of endometrial biopsy. Certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADEPro tool.

Results

The probability of live birth was significantly higher in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (relative risk-RR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.05–1.20; heterogeneity: I2=46.30%, p<0.001, 28 studies; low certainty). The probability of ongoing pregnancy was not significantly difference between the two groups (RR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.98–1.18; heterogeneity: I2=27.44%, p=0.15, 11 studies; low certainty). The probability of clinical pregnancy was significantly higher in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (RR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.06–1.18; heterogeneity: I2=47.48%, p<0.001, 37 studies; low certainty).

A subgroup analysis was performed based on the time that endometrial scratching was carried out. When endometrial scratching was performed during the menstrual cycle prior to the embryo transfer cycle a significantly higher probability of live birth was present (RR: 1.18, 95% CI:1.09-1.27; heterogeneity: I2=39.72%, p<0.001, 21 studies; moderate certainty). On the contrary, no effect on the probability of live birth was present when endometrial injury was performed during the embryo transfer cycle (RR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.67-1.15; heterogeneity: I2=65.18%, p=0.33, 5 studies; low certainty).

In addition, a higher probability of live birth was only present in women with previous IVF failures (RR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.20-1.53; heterogeneity: I2=0%, p<0.001, 13 studies; moderate certainty) with evidence suggesting that the more IVF failures the more likely endometrial scratching to be beneficial (p=0.004). The number of times endometrial scratching was performed, as well as the type of instrument used did not appear to affect the probability of live birth.

Conclusions

Endometrial scratching during the menstrual cycle prior to an embryo transfer cycle can lead to a higher probability of live birth in patients with previous IVF failures.

PROSPERO registration

PROSPERO CRD42023433538 (18 Jun 2023)

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Success rate following assisted reproductive technologies (ART) remain low. This has stimulated researchers worldwide to investigate the two main factors responsible for the achievement of pregnancy, namely embryo quality and endometrial receptivity. Regarding the latter, a variety of strategies have been proposed to enhance endometrial receptivity and thus increase the probability of pregnancy after ART.

Endometrial scratching is a procedure undertaken to purposely disrupt the endometrium in women aiming to get pregnant, since this intervention has been suggested to increase the chance of embryo implantation [1]. A considerable number of relevant observational and randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) have been published. These have been summarized in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which suggested the presence of a positive effect of endometrial scratching on the probability of pregnancy [2, 3].

Due to these initial findings, endometrial scratching was implemented as a standard procedure prior to IVF in many fertility clinics throughout the world [4]. However, a large RCT published in 2019 suggested no benefit from the procedure [5], and this led the scientific community to revisit the idea of endometrial scratching [6]. The most recent Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2021 included 38 trials and suggested that the effect of endometrial injury on the probability of live birth and clinical pregnancy among women undergoing IVF is unclear [7]. In the same year, a large multi-centered randomised controlled trial (SCRaTCH) suggested, marginally non-statistically significant, but clinically important differences of endometrial scratching on live birth rates [8, 9]. This once again fuelled the controversy regarding the potential benefit of endometrial scratching, pointing to the need for further evaluation [10]. In the presence of additional RCTs published after 2021, this systematic review and meta-analysis will attempt to clarify the contentious role of endometrial scratching prior to in vitro fertilization on the probability of pregnancy, expressed as live birth, ongoing or clinical pregnancy in specific subgroups, depending on the population studied and the method of endometrial scratching used.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A computerized literature search in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus and Web of Science covering the period until June 2023 was performed independently by two reviewers (MCI and CAV) aiming to identify RCTs that evaluated the following research question: does endometrial scratching undertaken prior to an IVF cycle increase the probability of live birth compared to or placebo/sham or no intervention? For this purpose, the free-text search terms [(endometr*) AND (scratch* OR injur* OR traum* OR biops* OR sampl* OR damag* OR activat* OR stimulat*)] AND [(in vitro fertilization) OR (in vitro fertilisation) OR IVF OR ICSI OR (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) OR (assisted reproduct*) OR (assisted conception)] AND [(random* OR (clinical trial) OR placebo OR sham)] were used. Additionally, the citation lists of relevant publications and previous systematic reviews were hand-searched. In case of overlapping reports (i.e. reports of the same RCT), the more extensive one was included.

No language limitations were applied. Authors of this article report no conflict of interest with any commercial entity, whose products are described, reviewed, evaluated, or compared in this study.

Selection of studies

Criteria for inclusion/exclusion of studies were established prior to the literature search and the protocol was published to the PROSPERO registry (CRD42023433538). Studies had to fulfill the following criteria for eligibility: a) randomized controlled trials comparing patients who underwent endometrial scratching prior to embryo transfer compared with those who did not, regardless of the type of procedure used to scratch the endometrium and the protocols of ovarian stimulation for IVF and/or endometrial preparation. Selection of the studies was performed independently by two of the reviewers (MCI and CAV). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each of the eligible studies: demographic (type of study, citation data, country, study period, number of patients included, methodological (randomization method, allocation concealment, blinding, whether power analysis was performed, primary outcome assessed, whether there was financial support for the trial, whether there was a protocol registration) (Table 1), procedural (inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, type of embryo transfer (fresh/ frozen), method of endometrial injury, timing of intervention, instrument used, control/ type of intervention, timing of control intervention, other interventions, definitions of pregnancy outcomes) (Table 2), outcome data (live birth rate per randomized patient, ongoing pregnancy per randomized patient, clinical pregnancy rate per randomized patient, cumulative live birth rate, miscarriage rate, ectopic pregnancy rate, multiple pregnancy rate, pain during the procedure using Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) measures, adverse events [e.g., infection, uterine perforation, uterine adhesions, bleeding]). Any disagreement was resolved unanimously by discussion. An effort was made to contact the authors of the eligible studies to retrieve missing or additional information, where necessary.

Outcome parameters

The main outcome measures were live birth rate per randomized patient, ongoing pregnancy (positive fetal heartbeat on ultrasound at 10-12 weeks of gestation) per randomized patient and clinical pregnancy rate (presence of gestational sac on ultrasound at a gestational age of 6-7 weeks) per randomized patient. Additional outcome measures were cumulative live birth rate (pregnancy achieved within 6 months after randomization), miscarriage rate, ectopic pregnancy rate, multiple pregnancy rate (presence of more than one gestational sac on transvaginal ultrasound), pain during the procedure using visual analogue scale (VAS) and adverse events (i.e. infection, dizziness, fever).

Quality of included studies

The methodological characteristics of included studies were extracted and appraised while the risk of bias of individual RCTs was formally assessed using RoB-2 [49].

Quantitative data synthesis

The dichotomous data results for each of the eligible for meta-analysis studies were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and they were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. These results were combined for meta-analysis using the Mantel/Haenszel model when using the fixed effects model and the restricted maximum likelihood method with Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman correction [50, 51] when using the random effects model (in case of high heterogeneity, i.e. I2≥50%). All results were combined for meta-analysis with the STATA Software (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.). Statistical heterogeneity was estimated with the I2 statistic [52].

Prespecified subgroup analyses for live birth (being the most clinically important of the main outcomes) were performed according to a) the device used to perform endometrial scratching, b) the timing of the endometrial scratching, c) whether single or double endometrial scratching was performed, d) whether the population studied had previous failed IVF cycles or not, and d) the minimum number of previous failed IVF cycles of the population analyzed. This latter factor was also explored through meta-regression [53].

Statistical significance was set at a p level of 0.05. Publication bias was explored using the Harbord test [54]. A sensitivity analysis was performed for live birth, ongoing pregnancy and clinical pregnancy by excluding studies judged to be overall at high risk of bias according to RoB-2.

The certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADEpro GDT (GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software]. McMaster University and Evidence Prime, 2022. Available from gradepro.org) (Supplementary Table 1). For outcomes where a beneficial effect was suggested by the evidence, the number-needed-to treat (NNT) (i.e. number of patients required to receive the endometrial scratch in order for an additional person to either incur or avoid the event of interest) was also calculated to illustrate the impact and efficacy of endometrial injury.

Results

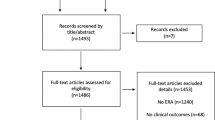

The literature search yielded 879 potentially relevant reports (Fig. 1). Subsequently, the titles of these manuscripts were examined, resulting in 222 potentially eligible publications. The abstracts of these studies were then examined and eventually 96 manuscripts that could provide data to answer the research question were identified. The full text of these studies was examined thoroughly, resulting in the inclusion of 40 publications, that represent 39 RCTs [5, 8, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 47, 48] (one report [46] contained post-hoc analyses of a previously published RCT [41] (Table 1). It should also be noted that Liu et al., [29] included four groups in their study (intervention and no intervention during the follicular and the luteal phase of the cycle preceding IVF) and therefore, we analyzed the follicular and the luteal phase arms of the study separately. Characteristics of the reports included in the systematic review appear in Tables 1 and 2. Eligible studies were published between 2008 and 2022. Randomization method was reported in 34 of the publications included, while allocation concealment method was reported in 19 of the studies included (Table 1). Most studies did not state clearly if the participants or those involved in the analysis were blinded to the type of intervention. Only 3 studies were reported to be single-blind and 3 were reported to be double-blind. Financial support was declared in 20 studies (Table 1). The largest study published so far on this issue was by Lensen et al. in 2019 [5]. The risk of bias assessment of the eligible studies is presented in Table 3. Overall, 9 studies [11,12,13, 15, 16, 23, 27, 28, 37] were deemed to be at high risk of bias (Supplementary Figures 1 & 2).

Meta-analysis

Live birth

A significantly higher probability of live birth was present in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (risk ratio-RR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.05– 1.20; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=46.30%, 28 studies, 29 datasets, 7425 patients; low certainty; NNT: 30) (Fig. 2). Publication bias did not seem to be present (p=0.727). A sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias [13, 15, 16, 23, 27, 37] did not materially change the results obtained (RR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.05-1.21; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=29.87%, 22 studies, 23 datasets; moderate certainty; NNT: 28) (Supplementary Figure 3).

Ongoing pregnancy

A higher, but not significantly so, probability of ongoing pregnancy was present in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (RR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.98– 1.18; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=27.44%, 11 studies, 11 datasets, 4515 patient; low certainty) (Fig. 3). Publication bias did not seem to be present (p=0.494). A sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias did not materially change the results obtained (RR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.97-1.18; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=0.00%, 8 studies, 8 datasets; moderate certainty) (Supplementary Figure 4).

Clinical pregnancy

A significantly higher probability of clinical pregnancy was present in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (RR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.06– 1.18; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=47.48%, 37 studies, 38 datasets, 8804 patients; low certainty; NNT: 27) (Fig. 4). Publication bias did not seem to be present (p=0.514). A sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias did not materially change the results obtained (RR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.05-1.19; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=21.88%, 21 studies, 22 datasets; moderate certainty; NNT: 25) (Supplementary Figure 5).

Cumulative live birth

A higher, but not significantly so, probability of cumulative live birth was present in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (RR: 1.11, 95% CI: 0.99–1.24; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=0%, 2 studies, 1298 patients; very low certainty) (Supplementary Figure 6). Publication bias could not be assessed due to the small number of available studies.

Miscarriage

No significant difference in the probability of miscarriage was present in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (RR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.75–1.06; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=0%, 24 studies, 25 datasets, 2568 patients; low certainty) (Supplementary Figure 7). Publication bias did not seem to be present (p=0.432).

Ectopic pregnancy

No significant difference in the probability of ectopic pregnancy was present in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (RR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.46– 2.27; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=0%, 8 studies, 9 datasets, 1219 patients; very low certainty) (Supplementary Figure 8). Publication bias did not seem to be present (p=0.148).

Multiple pregnancy

No significant difference in the probability of multiple pregnancy was present in embryo transfer cycles after endometrial scratching as compared to placebo/sham or no intervention (RR: 1.11, 95% CI: 0.92–1.35; fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=25.68%, 17 studies, 18 datasets, 1974 patients; low certainty) (Supplementary Figure 9). Publication bias did not seem to be present (p=0.482).

Adverse events

Pain

Five studies [4, 8, 19, 36, 44] reported pain in the endometrial scratching group with VAS scores ranging from 3.5 to 6.4. Only one study (158 patients) provided VAS scores both in the endometrial scratching group and the control group (sham procedure) indicating higher pain scores (6.42, SD (2.35) vs 1.82, SD (1.52); P < 0.001) in women who had the endometrial scratching [19].

Bleeding

In patients allocated to endometrial scratching, bleeding was reported in a proportion of them in four studies [5, 8, 33, 42], while in further 8 studies [13, 19, 23, 29, 38, 39, 41, 43] no patients experienced bleeding after endometrial scratching The remaining studies did not report on this adverse event.

Infection

In patients allocated to endometrial scratching no infections were observed in 11 studies [5, 8, 13, 19, 23, 29, 38, 39, 41,42,43], while the remaining studies did not report on this adverse event.

Dizziness

In patients allocated to endometrial scratching, dizziness was not observed in 10 studies [8, 13, 19, 23, 29, 38, 39, 41,42,43] while in a single study [5] 7 out of 690 patients (~1%) who underwent endometrial scratching experienced this adverse event.

Fever

In patients allocated to endometrial scratching, fever was not observed in 10 studies [5, 13, 19, 23, 29, 39, 41,42,43] while in a single study [8] 3 out of 742 patients (0.6%) who underwent endometrial scratching experienced this adverse event.

Subgroup analyses

Type of instrument used to perform the endometrial injury

Pipelle-type catheters were used for endometrial scratching in 29 trials, while Novak curette was the tool of choice in 3 trials. A variety of other instruments were used for endometrial injury in the remaining studies (Table 2). The type of instrument used to perform endometrial scratching did not appear to be associated with the effect size observed (test for subgroup differences: p=0.13).

Timing of the endometrial injury

Endometrial scratching was performed during the cycle preceding IVF treatment in 33 RCTs (Table 2). In a single study, endometrial scratching was performed from day 3 of the cycle preceding embryo transfer until day 3 of the treatment cycle [5]. In 3 of the eligible RCTs, endometrial scratching was performed during the follicular phase of the cycle, while in further 3 RCTs it was performed on the day of oocyte retrieval (Table 2).

A subgroup analysis based on the time endometrial scratching was performed (in the preceding cycle, in the actual embryo transfer cycle or in either of the two) suggested significant difference between the subgroups (p=0.04) (Supplementary Figure 10). Studies in which the endometrial scratching was performed during the preceding cycle showed a pooled RR: 1.18 (95% CI:1.09-1.27; moderate certainty; NNT: 21), whereas studies in which the endometrial scratching was performed during the embryo transfer cycle showed a pooled RR: 0.87 (95% CI: 0.67-1.15; low certainty).

Single of double endometrial injury

Single or double endometrial scratching was performed in 34 and 5 of the eligible RCTs, respectively (Table 2). A subgroup analysis between studies with single and those with double endometrial scratching did not suggest a significant difference in the probability of live birth (p=0.27).

History of previous failed IVF cycles

A subgroup analysis according to whether the population evaluated in each study had experienced previous IVF failures or not suggested a significant difference between subgroups (p<0.001). The highest effect size was observed in studies which randomized patients with previous IVF failures (RR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.20-1.53, fixed effects model, heterogeneity: I2=0.06%, 13 studies, 13 datasets, 2627 patients; moderate certainty; NNT: 14) (Supplementary Figure 11).

A further subgroup analysis according to the minimum number of previous IVF failures (0,1,2 and 3) also confirmed a significant difference between subgroups (p=0.04), with the largest effect size observed in studies that included patients with at least 3 failed IVF cycles (RR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.14-2.54, fixed effects model; heterogeneity: I2=49.75%, 3 studies, 547 patients; low certainty; NNT: 12) (Supplementary Figure 12). Finally, a meta-regression performed using the minimum number of previous failed as an independent variable, suggested a positive significant association with the risk ratio of live birth in the included studies (coeff: 0.18, 9% CI: 0.06-0.31; p=0.004).

Discussion

The aim of this review was to evaluate the impact of endometrial scratching on reproductive outcomes in women undergoing IVF compared to no intervention or sham intervention and to clarify if certain subgroups of patients could benefit more from it. Following the pooled analysis of 39 RCTs including ~9000 patients, this updated systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that endometrial scratching, compared to no or a sham intervention, can improve live birth and clinical pregnancy rates after IVF by a relative increase of 12%. This finding persisted in the sensitivity analysis performed where studies deemed to be at high risk of bias were excluded. On the other hand, this systematic review could not detect a significant positive effect on ongoing pregnancy rates, however, that analysis included only 11 RCTs and therefore a type II error cannot be excluded.

The most recent Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis has reviewed 37 studies published by June 2020 and eventually pooled data only from eight studies deemed to be at low risk of bias including in total 4402 patients. Regarding live birth, their pooled analysis did not detect a significant effect of endometrial scratching on live birth rates (odds ratio: 1.12, 95% CI: 0.98-1.28). Nevertheless, given the effect size observed, which suggests a potential (non-significant) benefit, the authors concluded that it is unclear whether a benefit truly exists. It should be noted that the lack of statistical significance could represent a type II error given the limited number of studies analyzed, which was a post-hoc decision and a departure from the review protocol. This post-hoc decision creates methodological challenges when interpreting the results of the Cochrane review, particularly since the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions suggests that sensitivity analyses are used to check the robustness of results by excluding studies at high risk of bias [55]. The present systematic review and meta-analysis has reviewed and analyzed the entire body of available evidence published until 2023 following established guidelines on dealing with potential bias.

Furthermore, the present systematic review has analyzed several potential effect moderators via subgroup analyses and meta-regression. These analyses suggested that the pooled effect size of studies where the endometrial injury was performed in the cycle before the embryo transfer was higher than that observed in studies where endometrial injury was performed for some or all patients during the actual embryo transfer cycle. The most recent Cochrane review, due to the restriction of the analysis to 8 RCTs, was not able to perform such a comparison. The implications of this finding can be significant as it has been argued [8, 10] that the timing of the biopsy is a clinically important variable.

Another important finding of the subgroup analyses is the potential significance of the type of population included in the eligible RCTs. The subgroup analysis comparing studies where patients recruited had previous failed IVF cycles or not (or there was a mix of both), strongly suggested that the intervention is far more likely to have a beneficial effect on patients with previous failed IVF cycles. This finding was confirmed in further subgroup analyses based on the minimum number of previous failed IVF cycles and the relevant meta-regression, both of which suggested that the higher the number of previous failed IVF cycles, the higher the risk ratio observed, implying a stronger benefit of endometrial scratching. The explanation of this finding could lie in the progressively better selection of poorer prognosis patients, more likely to have an endometrial issue who can benefit from the intervention, as it was suggested in the original report by Barash et al [1]. Other authors have also supported that hysteroscopy combined with endometrial injury is beneficial for patients with repeated IVF failures [56, 57]. The beneficial effect of endometrial injury in patients with prior failed embryo transfers has also previously been reported in a meta-analysis published in 2018 [3]. The latest Cochrane systematic review did not identify an association with previous IVF failures, however, the limited number of studies analyzed could once again have limited the statistical power of this test.

The subgroup analysis depending on whether endometrial scratching was performed once or twice on the same patient did not show any difference between the two subgroups compared. Moreover, the subgroup analysis depending on the type of device used to perform endometrial scratching did not suggest that this is important for the probability of live birth. The most recent Cochrane review did not address the same clinical questions, although it did compare higher with lower intensity of endometrial injury and failed to detect a difference in the effect sizes between the two methods. These findings suggest that performing endometrial scratching once with a pipelle catheter is likely to be sufficient for a beneficial effect to be elicited.

In terms of the remaining secondary outcomes, the present systematic review and meta-analysis did not find a difference in ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage and multiple pregnancy rates between women who had embryo transfer after endometrial scratching and those who had not. This is in agreement with what has been previously reported [7]. Other important outcomes in the evaluation of endometrial scratching are adverse events such as pain, bleeding, dizziness, infection and fever. A comparative assessment of the incidence of such adverse events would only be possible in studies that performed a sham procedure in the control group. In the present systematic review only one study [19] provided such data indicating higher pain experienced in women who had endometrial scratching compared to those who had the sham procedure. However, what might be of more clinical relevance is the incidence of such adverse events in women undergoing endometrial scratching. The incidence of pain and/or bleeding varied widely in the included studies from 0% to 75%, likely reflecting differences in the methodologies used to capture these adverse events. Reassuringly, infection, dizziness and fever after endometrial biopsy was reported to be rare, with only one out of the eleven studies reporting dizziness [5] or fever [8] at a rate of ~1%, while the remaining 10 studies reported that none of the patients experienced these adverse events.

An individual participant data meta-analysis (IPD-MA) on the potential benefit of endometrial injury was recently published confirming that live birth rates are higher after endometrial injury compared to no scratch/sham procedure (odds ratio: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.02-1.64). Despite the obvious methodological advantages of an IPD-MA, the researchers were only able to include 13 RCTs (n=4112 participants) which is <50% of the sample size included in the present meta-analysis. This might explain why a significant interaction effect with the number of previous failed embryo transfers was not detected in the IPD-MA, something the present meta-analysis has been able to show by analyzing the total body of published evidence.

It should be noted that the present systematic review is also characterized by limitations such as the clinical heterogeneity in the eligible studies regarding the population studied and the method used to implement endometrial scratching that should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results obtained. To facilitate this interpretation several subgroup analyses have been performed to identify the potential moderating effect of these factors. The quality of the eligible studies also varied with some studies being graded as at high risk of bias. A sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding these studies and the results obtained were not materially different to the main analysis. Finally, most of the included studies did not seem to capture the adverse effects of endometrial scratching, and this information is important when counselling patients about the potential benefits and risks of the intervention.

The present systematic review and meta-analysis represents an updated critical appraisal of an intervention that has been extensively used in clinical practice during the last decade. Its results are able to inform clinicians and patients regarding important questions including, which patients might benefit from endometrial scratching, what is the optimal method of endometrial scratching and when it should be performed. Nevertheless, it is also evident from the present work that further data is required to confirm or rebut its findings and based on this systematic review future clinical research should focus on endometrial scratching during the cycle prior to IVF in patients with multiple previous IVF failures. Concurrently, future basic research needs to identify a plausible mechanism through which endometrial scratching exerts its observed beneficial effect.

In conclusion, the present systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that endometrial scratching during the menstrual cycle prior to IVF can lead to a higher probability of live birth in patients with previous IVF failures and that this effect seems to be greater in patients with more IVF failures.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Assisted reproductive technologies

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IVF:

-

In vitro fertilization

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Barash A, Dekel N, Fieldust S, Segal I, Schechtman E, Granot I. Local injury to the endometrium doubles the incidence of successful pregnancies in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(6):1317–22.

Nastri CO, Lensen SF, Gibreel A, Raine-Fenning N, Ferriani RA, Bhattacharya S, et al. Endometrial injury in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD009517.

Vitagliano A, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saccone G, Valenti G, Sapia F, Kamath MS, et al. Endometrial scratch injury for women with one or more previous failed embryo transfers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(4):687-702 e2.

Lensen S, Sadler L, Farquhar C. Endometrial scratching for subfertility: everyone’s doing it. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(6):1241–4.

Lensen S, Osavlyuk D, Armstrong S, Stadelmann C, Hennes A, Napier E, et al. A Randomized trial of endometrial scratching before in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):325–34.

Lensen S, Venetis C, Ng EHY, Young SL, Vitagliano A, Macklon NS, et al. Should we stop offering endometrial scratching prior to in vitro fertilization? Fertil Steril. 2019;111(6):1094–101.

Lensen SF, Armstrong S, Gibreel A, Nastri CO, Raine-Fenning N, Martins WP. Endometrial injury in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;6(6):CD009517.

van Hoogenhuijze NE, Mol F, Laven JSE, Groenewoud ER, Traas MAF, Janssen CAH, et al. Endometrial scratching in women with one failed IVF/ICSI cycle-outcomes of a randomised controlled trial (SCRaTCH). Hum Reprod. 2021;36(1):87–98.

Van Hoogenhuijze N, Torrance HL, Eijkemans MJC, Broekmans FJM. Twelve-month follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial studying endometrial scratching in women with one failed IVF/ICSI cycle (the SCRaTCH trial). Human Reproduction. 2020;35(SUPPL 1):i32.

Venetis CA. Endometrial injury before IVF: light at the end of the tunnel or false hope? Hum Reprod. 2021;36(1):1–2.

Karim Zadeh Meybodi M, Ayazi M, Tabibnejad N. Effect of endometrium local injury on pregnancy outcome in patients with IVF/ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:126.

Karimzadeh MA, Ayazi Rozbahani M, Tabibnejad N. Endometrial local injury improves the pregnancy rate among recurrent implantation failure patients undergoing in vitro fertilisation/intra cytoplasmic sperm injection: a randomised clinical trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(6):677–80.

Karimzade MA, Oskouian H, Ahmadi S, Oskouian L. Local injury to the endometrium on the day of oocyte retrieval has a negative impact on implantation in assisted reproductive cycles: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(3):499–503.

Narvekar S, Gupta N, Shetty N, Kottur A, Srinivas M, Rao K. Does local endometrial injury in the nontransfer cycle improve the IVF-ET outcome in the subsequent cycle in patients with previous unsuccessful IVF A randomized controlled pilot study. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2010;3(1):15–9.

Safdarian L, Movahedi S, Aleyasine A, Aghahosaini M, Fallah P, Rezaiian Z. Local injury to the endometrium does not improve the implantation rate in good responder patients undergoing in-vitro fertilization. Iran J Reprod Med. 2011;9(4):285–8.

Baum M, Yerushalmi GM, Maman E, Kedem A, MacHtinger R, Hourvitz A, et al. Does local injury to the endometrium before IVF cycle really affect treatment outcome? Results of a randomized placebo controlled trial. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28(12):933–6.

Inal ZHO, Gorkemli H, Inal HA. The effect of local injury to the endometrium for implantation and pregnancy rates in ICSI -ET cycles with implantation failure: A randomised controlled study. Eur J Gen Med. 2012;9(4):223–9.

Shohayeb A, El-Khayat W. Does a single endometrial biopsy regimen (S-EBR) improve ICSI outcome in patients with repeated implantation failure? A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;164(2):176–9.

Nastri CO, Ferriani RA, Raine-Fenning N, Martins WP. Endometrial scratching performed in the non-transfer cycle and outcome of assisted reproduction: a randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(4):375–82.

Guven S, Kart C, Unsal MA, Yildirim O, Odaci E, Yulug E. Endometrial injury may increase the clinical pregnancy rate in normoresponders undergoing long agonist protocol ICSI cycles with single embryo transfer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;173:58–62.

Yeung TW, Chai J, Li RH, Lee VC, Ho PC, Ng EH. The effect of endometrial injury on ongoing pregnancy rate in unselected subfertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(11):2474–81.

Gibreel A, El-Adawi N, Elgindy E, Al-Inany H, Allakany N, Tournaye H. Endometrial scratching for women with previous IVF failure undergoing IVF treatment. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(4):313–6.

Singh N, Toshyan V, Kumar S, Vanamail P, Madhu M. Does endometrial injury enhances implantation in recurrent in-vitro fertilization failures? A prospective randomized control study from tertiary care center. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2015;8(4):218–23.

Xu B, Zhang Q, Hao J, Xu D, Li Y. Two protocols to treat thin endometrium with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor during frozen embryo transfer cycles. Reprod BioMed Online. 2015;30(4):349–58.

Zhang XL, Fu YL, Kang Y, Qi C, Zhang QH, Kuang YP. Clinical observations of sequential therapy with Chinese medicine and hysteroscopic mechanical stimulation of the endometrium in infertile patients with repeated implantation failure undergoing frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21(4):249–53.

Aflatoonian A, Baradaran Bagheri R, Hosseinisadat R. The effect of endometrial injury on pregnancy rate in frozen-thawed embryo transfer: a randomized control trial. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14(7):453–158.

Shahrokh-Tehraninejad E, Dashti M, Hossein-Rashidi B, Azimi-Nekoo E, Haghollahi F, Kalantari V. A randomized trial to evaluate the effect of local endometrial injury on the clinical pregnancy rate of frozen embryo transfer cycles in patients with repeated implantation failure. J Family Reprod Health. 2016;10(3):108–14.

Zygula A, Szymusik I, Marianowski P. The effect of endometrial pipelle biopsy on clinical pregnancy rate in women with previous IVF failure undergoing IVF treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;206:e127.

Liu W, Tal R, Chao H, Liu M, Liu Y. Effect of local endometrial injury in proliferative vs. luteal phase on IVF outcomes in unselected subfertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2017;15(1):75.

Mak JSM, Chung CHS, Chung JPW, Kong GWS, Saravelos SH, Cheung LP, et al. The effect of endometrial scratch on natural-cycle cryopreserved embryo transfer outcomes: a randomized controlled study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;35(1):28–36.

Tk A, Singhala H, Premkumarb PS, Acharyaa M, Kamath MS, Georgec K. Local endometrial injury in women with failed IVF undergoing a repeat cycle: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;214:109–14.

Maged AM, Rashwan H, AbdelAziz S, Ramadan W, Mostafa WAI, Metwally AA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of endometrial injury on implantation and clinical pregnancy rates during the first ICSI cycle. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140(2):211–6.

Pecorino B, Scibilia G, Rapisarda F, Borzi P, Vento ME, Teodoro MC, et al. Evaluation of implantation and clinical pregnancy rates after endometrial scratching in women with recurrent implantation failure. Italian J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;30(2):39–44.

Sherif A, Abou-Talib Y, Ibrahim M, Arafat R. The effect of day 6 endometrial injury of the ICSI cycle on pregnancy rate: a randomized controlled trial. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2018;23(4):292–6.

Eskew AM, Reschke LD, Woolfolk C, Schulte MB, Boots CE, Broughton DE, et al. Effect of endometrial mechanical stimulation in an unselected population undergoing in vitro fertilization: futility analysis of a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36(2):299–305.

Frantz S, Parinaud J, Kret M, Rocher-Escriva G, Papaxanthos-Roche A, Creux H, et al. Decrease in pregnancy rate after endometrial scratch in women undergoing a first or second in vitro fertilization. A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(1):92–9.

Gurgan T, Kalem Z, Kalem MN, Ruso H, Benkhalifa M, Makrigiannakis A. Systematic and standardized hysteroscopic endometrial injury for treatment of recurrent implantation failure. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39(3):477–83.

Hilton J, Liu KE, Laskin CA, Havelock J. Effect of endometrial injury on in vitro fertilization pregnancy rates: a randomized, multicentre study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299(4):1159–64.

Olesen MS, Hauge B, Ohrt L, Olesen TN, Roskaer J, Baek V, et al. Therapeutic endometrial scratching and implantation after in vitro fertilization: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(6):1015–21.

Berntsen S, Hare KJ, Lossl K, Bogstad J, Palmo J, Praetorius L, et al. Endometrial scratch injury with office hysteroscopy before IVF/ICSI: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:112–7.

Izquierdo Rodriguez A, de la Fuente Bitaine L, Spies K, Lora D, Galindo A. Endometrial Scratching Effect on Clinical Pregnancy Rates in Patients Undergoing Egg Donor In Vitro Fertilization Cycles: the ENDOSCRATCH Randomized Clinical Trial (NCT03108157). Reprod Sci. 2020;27(10):1863–72.

Mackens S, Racca A, Van de Velde H, Drakopoulos P, Tournaye H, Stoop D, et al. Follicular-phase endometrial scratching: a truncated randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(5):1090–8.

Tang Z, Hong M, He F, Huang D, Dai Z, Xuan H, et al. Effect of endometrial injury during menstruation on clinical outcomes in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a randomized control trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46(3):451–8.

Metwally M, Chatters R, Dimairo M, Walters S, Pye C, White D, et al. A randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and safety of the endometrial scratch procedure prior to first-time IVF, with or without ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2021;36(7):1841–53.

Zahiri Z, Sarrafzadeh Y, Kazem Nejad Leili E, Sheibani A. Success Rate of Hysteroscopy and Endometrial Scratching in Repeated Implantation Failure: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Cited 28/09/2023;10:e1399. Available from: https://www.journals.salviapub.com/index.php/gmj/article/view/1399.

Izquierdo A, de la Fuente L, Spies K, Lora D, Galindo A. Cumulative live birth rates in egg donor IVF cycles with or without endometrial scratching: Is there a residual effect in subsequent embryo transfers? Follow-up results of a RCT in clinical practice. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022;51(4):102335. (Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2468784722000277).

Noori N, Ghaemdoust F, Ghasemi M, Liavaly M, Keikha N, Dehghan Haghighi J. The effect of endometrial scratching on reproductive outcomes in infertile women undergoing IVF treatment cycles. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;42(8):3611–5.

Turktekin N, Karakus C, Ozyurt R. Endometrial injury and fertility outcome on the day of oocyte retrieval. Ann Clin Analytical Med. 2022;13(1):89–92.

Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

Hartung J, Knapp G. A refined method for the meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with binary outcome. Stat Med. 2001;20(24):3875–89.

IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:25.

Deeks JJ HJ, Altman DJ. Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. 2008.

Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1559–73.

Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25(20):3443–57.

Deeks J, Higgins J, Altman D, Group obotCSM. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3: Cochrane; 2023. Cited 2023 25/07/2023. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Orvieto R, Meltcer S, Liberty G, Rabinson J, Anteby EY, Nahum R. A combined approach to patients with repeated IVF failures. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2462–4.

Orvieto R. A simplified universal approach to COH protocol for IVF: ultrashort flare GnRH-agonist/GnRH-antagonist protocol with tailored mode and timing of final follicular maturation. J Ovarian Res. 2015;8:69.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the authors of the original RCTs (A.M. Maged, S. Frantz, S. Mackens and N. Van Hoogenhuijze) who provided further information through correspondence.

Funding

No funding was required for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MCI co-drafted the protocol of the study, contributed to the literature search and screening of studies, extracted the data and drafted the manuscript. EMK contributed to the protocol of this study, the statistical analysis, the interpretation of results and critical review of the manuscript. LZ contributed to the protocol of this study, the interpretation of results and the critical review of the manuscript. CAV conceived the idea of this study, co-drafted the protocol of the study, contributed to the literature search and screening of studies, extracted the data, contributed to the statistical analysis and interpretation of results and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethics approval was required as this meta-analysis is based on published data. All data and materials of this systematic review are available upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

CAV is a Section Editor of Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. The remaining authors do not have any competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary Figure 1. Summary plot of the risk of bias assessment.

Additional file 2:

Supplementary Figure 2. Traffic lights plot of the risk of bias assessment.

Additional file 3:

Supplementary Figure 3. Forest plot presenting the sensitivity analysis (by excluding studies at high risk of bias) on the risk ratio of live birth raes between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention.

Additional file 4:

Supplementary Figure 4. Forest plot presenting the sensitivity analysis (by excluding studies at high risk of bias) on the risk ratio of ongoing pregnancy between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention.

Additional file 5:

Supplementary Figure 5. Forest plot presenting the sensitivity analysis (by excluding studies at high risk of bias) on the risk ratio of clinical pregnancy between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention.

Additional file 6:

Supplementary Figure 6. Forest plot presenting the risk ratio of cumulative live birth between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention.

Additional file 7:

Supplementary Figure 7. Forest plot presenting the risk ratio of miscarriage between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention.

Additional file 8:

Supplementary Figure 8. Forest plot presenting the risk ratio of ectopic pregnancy between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention.

Additional file 9:

Supplementary Figure 9. Forest plot presenting the risk ratio of multiple pregnancy between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention.

Additional file 10:

Supplementary Figure 10. Forest plot presenting the subgroup analysis of the risk ratio of live birth between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention according to the timing of endometrial injury.

Additional file 11:

Supplementary Figure 11. Forest plot presenting the subgroup analysis of the risk ratio of live birth between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention according to the whether the population included had a history of previous IVF failures or not.

Additional file 12:

Supplementary Figure 12. Forest plot presenting the subgroup analysis of the risk ratio of live birth between women who had endometrial scratching prior to their embryo transfer and those who had a placebo/sham procedure or no intervention according to the minimum number of previous IVF failures.

Additional file 13:

Supplementary Table 1. Certainty assessment of the available evidence using the GRADEPro Guideline Development Tool.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Iakovidou, M.C., Kolibianakis, E., Zepiridis, L. et al. The role of endometrial scratching prior to in vitro fertilization: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 21, 89 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-023-01141-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-023-01141-2