Abstract

Background

In some malignant tumors, a high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is connected with unfavorable prognosis. Nevertheless, the prognostic value of the NLR in gliomas remains disputed. The clinical significance of the NLR in gliomas was investigated in our study.

Methods

The databases, PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library, were searched using words like “glioma,” “glioblastoma,” “neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio,” and others through May 2019. We evaluated the significance of NLR on overall survival (OS) of patients with gliomas in our study.

Results

Finally, 16 cohorts with 2275 patients were analyzed. The pooled analysis revealed that an elevated NLR was connected with unfavorable OS (hazards ratio (HR): 1.43, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.27–1.62) outcomes of patients with gliomas.

Conclusion

A high NLR can be considered a high-risk prognostic factor in gliomas, and more adjuvant chemotherapy should be recommended for high-risk patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gliomas are the most frequent type of cerebral tumors. Approximately, 81% of primary intracranial tumors are gliomas [1]. The most challenging malignant glioma is glioblastoma (GBM; WHO grade IV); patients with GBM only have a median survival time of 14.6 months [1]. Despite the improvements in the multimodality treatment (maximal safe resection, radiation therapy concurrent with temozolomide, and subsequent adjuvant temozolomide chemotherapy) [2, 3], local recurrence and metastasis remain significant concerns in most patients. Therefore, it is necessary to identify biological markers for estimating the progression or survival of patients with glioma.

In clinical practice, traditional prognostic factors, including the Karnofsky performance status, tumor location, age at presentation, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) status, and extent of surgery, have gradually proved to be insufficient and inaccurate. The identification of economically feasible and readily available prognostic biomarkers could assist us in identifying high-risk patients to determine the best treatment options and further improve the prognosis of the patients. Inflammatory factors have to be related to cancer initiation, progression, invasion, and metastasis [4, 5]. In several types of cancers, biomarkers of inflammatory reactions have been considered as prognostic factors [6]. As a type of inflammatory parameter, it is easy to obtain the peripheral blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). Furthermore, in various cancers [7], an elevated NLR is considered as a poor prognostic factor. NLR is an important factor that influence prognosis in ovarian, colorectal, breast, pancreatic, urothelial, renal cell cancers, and myeloma patients [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Recently, elevated NLR was reported to be correlated with poor prognosis in patients with gliomas in several studies. However, the outcomes of published articles were inconsistent. Therefore, our study aimed to elucidate the clinical significance of NLR for gliomas.

Methods

Search strategy

The electronic databases, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase, were searched from the time of their conception until May 2019. The databases were searched using the following words: (‘glioblastoma’ OR ‘glioma’) AND (‘neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio’ OR ‘neutrophil lymphocyte ratio’ OR ‘neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio’ OR ‘NLR’) AND (‘survival’ OR ‘mortality’ OR ‘outcome’ OR ‘prognostic’ OR ‘prognosis’). We manually screened the references of the related articles to expand the search range.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria in our meta-analysis were as follows: (1) patients pathologically confirmed with gliomas, (2) the prognostic significance of peripheral blood NLR for gliomas was assessed, (3) cutoff of NLR was provided, and (4) hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for NLR on overall survival (OS) were available. The following studies were excluded: (1) case reports, letters, conference abstracts, non-clinical studies, and reviews without available data; (2) studies with insufficient information to evaluate HRs and 95% CIs; and (3) duplicated publications.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators independently selected the studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria and extracted the relevant information. The related information was extracted as follows: first author’s surname, country, sample size, age of the study population, publication year, histology, duration, treatment, cutoff value of NLR, sampling time, and HR and 95% CI for OS. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion.

Two reviewers used Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) [15] to evaluate the quality of studies. Using the NOS, the studies are evaluated on three ways, namely comparability, selection, and outcome confirmation. Each parameter also has subitems. The maximum score is nine stars, and NOS scores ≥ 5 is considered of high quality [15].

Statistical analysis

The collected data from the included studies were combined using Review Manager 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Forest plots were constructed to assess the predictive role of NLR in gliomas. HRs and 95% CIs for OS were synthesized with a random effect model. A random effect model or fixed effect model was employed depending on the heterogeneity of the studies [16]. The heterogeneity was evaluated with the I2 statistic. The data were synthesized using a fixed effect model with I2 < 25%. In case of I2 > 25%, a random effect model was used for data synthesis. The sources of heterogeneity were evaluated by subgroup analysis. Sensitivity analysis was used to appraise the stability of the outcome. Funnel plots were constructed to evaluate publication bias. Statistical difference was defined as P value < .05.

Results

Description of the trials

A flow diagram based on the PRISMA statement (Additional file 1) summarizing the process of study retrieval is illustrated in Fig. 1. A total of 16 articles published between 2013 and 2019 were incorporated in our study [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. The data of 2275 patients in whom the prognostic significance of NLR was assessed were included. The demographic data of the patients in the included trials is shown in Table 1. The NOS scoring details are presented in Additional file 2. There were 2 studies from USA, 8 from China, 1 from Canada, 1 from Russia, 2 from Turkey, 1 from Singapore, and 1 from Portugal. All trials were retrospective ones. The cutoff values ranged from 2.5 to 7.5 in the included trials, with an average value of 4.03. Eleven studies used NLR from the preoperative blood sample, whereas 2 used NLR from the postoperative blood sample. Thirteen of the 15 trials applied multivariate analysis. The NOS scores ranged from 5 to 7. The average number of NOS scores was 5.375.

NLR and OS in patients with gliomas

A high preoperative NLR was connected with unfavorable OS (HR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.27–1.62, P < 0.00001; Fig. 2) in patients with gliomas. The heterogeneity analysis among the studies showed an I2 value of 83% (P < 0.00001), which indicated obvious heterogeneity. A subgroup analysis was conducted on the basis of the latent confounding factors, such as histology, cutoff value of NLR, analysis method, ethnicity, NOS score, and sampling time. On stratification by ethnicity in the subgroup analysis, a low NLR predicted a positive prognosis in the Asian (HR: 1.64, 95% CI: 1.28–2.10), but not in the Caucasian (HR: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.92–1.72). Stratification by histology revealed that a low NLR predicted longer OS in trials with patients with gliomas of various grades (HR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.40–2.01) and in those patients with GBM (HR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.13–1.47). Furthermore, the subgroup analysis according to the cutoff value of NLR indicated that a high NLR was connected with negative OS in patients with gliomas in trials with cutoff value of NLR = 4 (HR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.22–1.97) and in those in trials with cutoff values of NLR ≠ 4 (HR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.06–2.19). Results of the subgroup analysis on the basis of the NOS score suggested that high NLR was connected with poor OS when the NOS score was ≤ 5 (HR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.17–1.83) and NOS score was > 5 (HR: 1.72, 95% CI: 1.09–2.72). Results of the subgroup analysis on the basis of the analysis method showed that a low NLR represented good prognostic significance in both the univariate analysis (HR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.06–2.67) and multivariate analysis (HR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.16–1.48). Finally, analysis on the subgroup of sampling time indicated that an elevated NLR was connected with negative OS in gliomas with preoperative blood sampling (HR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.14–1.45), but not in those with postoperative blood sampling (HR: 1.36, 95% CI: 0.69–2.70) (Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

To appraise the impact of each research on the overall outcome (HR) of OS, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. As for the HR on overall survival, we removed each study individually and the HR value or degree of significance did not substantially change.

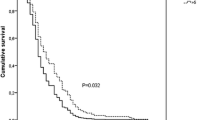

The shape of the funnel plots showed asymmetry and indicated significant publication bias in OS (Fig. 3).

Discussion

To illuminate the relationship between NLR and gliomas, we conducted a meta-analysis by consolidating the published literature. In the current study, we incorporated 16 studies with 2275 patients to assess the clinical significance of NLR in gliomas. Our study indicated that a high preoperative NLR was connected with unfavorable OS in gliomas.

The role of NLR has been studied in other cancers, including colorectal, ovarian, breast, pancreatic, urothelial, and renal cell cancers, myeloma, and others [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. The results of our pooled analysis are in agreement with results from these abovementioned studies on other cancers.

The mechanisms behind the relationship between a high NLR and unfavorable OS in gliomas have not been clearly illuminated. One possible mechanism could be the relationship between NLR and inflammatory response. A high NLR indicates relative neutrophilia and lymphopenia. Neutrophilia inhibits immune cells such as lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and activated T cells [33, 34]. This could stimulate the proliferation of cancer cells. On the other hand, in several studies, the role of lymphocytes has been presented, showing that lymphocyte infiltration of tumor cells has been associated with better response to treatment [35]. Thus, NLR might be regarded as a crude measure to reflect the balance between immunocytes and neutrophils. Moreover, it is an easily obtained and cost-effective index in clinical work, thus making it an attractive prognostic index for gliomas.

Notably, half of included articles in our study are from China; therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis of the studies based on ethnicity, to explore whether race had any effect on the outcome. On stratification by ethnicity in the subgroup analysis, a low NLR predicted a positive prognosis in the Asians, but not in the Caucasians. Twelve of the 16 included studies were from Asia, which may cause selection bias. In the future, relevant trials are needed to provide further evidence for the prognostic significance of NLR on race. In addition, analysis on the basis of sampling time indicated that an elevated NLR was connected with negative OS in gliomas with preoperative blood sampling, but not in those with postoperative blood sampling. Complex factors may influence the NLR value. It is suggested that pretreatment NLR should be used to estimate prognosis in clinical practice.

In our study, there are some limitations. First, all of incorporated trials are retrospective ones. Second, because of lack of individual patient data, the optimal NLR cutoff value could not be provided for clinical practice. Future studies are needed to explore the best NLR cutoff value. Third, the study has a publication bias. As mentioned previously, an obvious bias in the OS for glioma patients is present. There may be various factors contributing to publication bias. In my view, apart from the factors such as termination of publication and negative results not being published, the language limitation may be the main factor, as our searching language was mainly English. Finally, detailed information of unknown pretreatment (i.e., physical conditions, comorbidities, infective symptoms, medication, hypertension, lifestyle habits, and diabetes mellitus) could influence the NLR value, thus weakening its actual relationship with cancer-specific endpoints.

Despite these limitations, some advantages of our meta-analysis exist. First, most of the data were obtained from multivariate analysis, with three studies providing univariate outcomes. In our subgroup analysis, a low NLR represented good prognostic significance for glioma patients both with the univariate and multivariate analysis methods (Table 2). Additionally, NLR is an easily available biomarker. It can be obtained during the routine checkup. It is also an ideal index as obtaining it is economically cheap and fast. In the future, well-designed prospective trials with longer follow-up periods and further confirmatory trials are needed to provide further evidence of the prognostic significance of NLR in screening high-risk patients with gliomas.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a high NLR is related to poor survival in patients with gliomas. NLR may serve as a cost-effective prognostic biomarker to identify high-risk patients who might need further therapy. More high-quality prospective trials are needed to assess the practicability of NLR in gliomas.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IDH:

-

Isocitrate dehydrogenase

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale

- OS:

-

Overall survival

References

QT O, H G LS, SM V, JS B-S. Epidemiology of gliomas. Cancer Treat Res. 2015;163:1–14.

Stupp R, Mason WP, MJvd B, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96.

Kawano H, Hirano H, Yonezawa H, Yunoue S, Yatsushiro K, Ogita M, et al. Improvement in treatment results of glioblastoma over the last three decades and benefi cial factors. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:206–12.

O’Callaghan DS, O’Donnell D, O’Connell F, O’Byrne KJ. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(12):2024–36.

Aggarwal BB, Vijayalekshmi RV, Sung B. Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: short-term friend, long-term foe. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(2):425–30.

McMillan DC. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score: a decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(5):534–40.

Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocana A, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju124.

Liu X, Qu JK, Zhang J, Yan Y, Zhao XX, Wang JZ, et al. Prognostic role of pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(45):e8101.

Zhou Y, Wei Q, Fan J, Cheng S, Ding W, Hua Z. Prognostic role of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis containing 8252 patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;479:181–9.

Mu S, Ai L, Fan F, Sun C, Hu Y. Prognostic role of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in multiple myeloma: a dose-response meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:499–507.

Zhang J, Zhang H-Y, Li J, Shao X-Y, Zhang C-X. The elevated NLR, PLR and PLT May predict the prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(40):68837–46.

Zhou Q, Hong L, Zuo M-Z, He Z. Prognostic significance of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in ovarian cancer: evidence from 4,910 patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(40):68938–49.

Semeniuk-Wojtas A, Lubas A, Stec R, Syrylo T, Niemczyk S, Szczylik C. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and C-reactive protein as new and simple prognostic factors in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16(3):e685–e93.

Vartolomei MD, Kimura S, Ferro M, Vartolomei L, Foerster B, Abufaraj M, et al. Is neutrophil-to-lymphocytes ratio a clinical relevant preoperative biomarker in upper tract urothelial carcinoma? A meta-analysis of 4385 patients. World J Urol. 2018;36(7):1019–29.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Bambury RM, Teo MY, Power DG, Yusuf A, Murray S, Battley JE, et al. The association of pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with overall survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J Neuro-Oncol. 2013;114(1):149–54.

Han S, Liu Y, Li Q, Li Z, Hou H, Wu A. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with neutrophil and T-cell infiltration and predicts clinical outcome in patients with glioblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:617.

Auezova R, Ryskeldiev N, Doskaliyev A, Kuanyshev Y, Zhetpisbaev B, Aldiyarova N, et al. Association of preoperative levels of selected blood inflammatory markers with prognosis in gliomas. OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9:6111–7.

Kaya V, Yildirim M, Yazici G, Yalcin AY, Orhan N, Guzel A. Prognostic significance of indicators of systemic inflammatory responses in glioblastoma patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(12):3287–91.

Lopes M, Carvalho B, Vaz R, Linhares P. Influence of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in prognosis of glioblastoma multiforme. J Neuro-Oncol. 2017;136(1):173–80.

Mason M, Maurice C, McNamara MG, Tieu MT, Lwin Z, Millar B-A, et al. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio dynamics during concurrent chemo-radiotherapy for glioblastoma is an independent predictor for overall survival. J Neuro-Oncol. 2017;132(3):463–71.

Wang PF, Song HW, Cai HQ, Kong LW, Yao K, Jiang T, et al. Preoperative inflammation markers and IDH mutation status predict glioblastoma patient survival. Oncotarget. 2017;8(30):50117–23.

Wiencke JK, Koestler DC, Salas LA, Wiemels JL, Roy RP, Hansen HM, et al. Immunomethylomic approach to explore the blood neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in glioma survival. Clin Epigenetics. 2017;9:10.

Wang J, Xiao W, Chen W, Hu Y. Prognostic significance of preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with glioma. EXCLI J. 2018;17:505–12.

Weng W, Chen X, Gong S, Guo L, Zhang X. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio correlated with glioma grading and glioblastoma survival. Neurol Res. 2018;40(11):917–22.

Yersal O, Odabasi E, Ozdemir O, Kemal Y. Prognostic significance of pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with glioblastoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;9(4):453–8.

Bao Y, Yang M, Jin C, Hou S, Shi B, Shi J, et al. Preoperative hematologic inflammatory markers as prognostic factors in patients with glioma. World Neurosurg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.252.

Ng SSQ, Chua GWY, Kusumawidjaja G, Wong FY, Tham CK, Chua ET, et al. Evaluation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic biomarkers for elderly patients with glioblastoma treated with chemoradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2017;99(2):E97.

YANG T, MAO P, CHEN X, NIU X, XU G, BAI X, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers in prognostic analysis for patients with glioma and the establishment of a nomogram. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:2516–22.

Hao Y, Li X, Chen H, Huo H, Liu Z, Tian F, et al. A cumulative score based on preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and fibrinogen in predicting overall survival of patients with glioblastoma multiforme. World Neurosurg. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.169.

Gan Y, Zhou X, Niu X, Li J, Wang T, Zhang H, et al. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic factor in elderly patients with high-grade gliomas. World Neurosurg. 2019;127:e261–e7.

HT PETRIE, LW KLASSEN, HD KAY. Inhibition of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in vitro by autologous peripheral blood granulocytes. J Immunol. 1985;134(1):230–4.

EL-HAG A. CLARK' RA. Immunosuppression by activated human neutrophils. Dependence on the myeloperoxidase system. J Immunol. 1987;139(7):2406–13.

Gooden MJ, de Bock GH, Leffers N, Daemen T, Nijman HW. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(1):93–103.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS and YL conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. YL and YL searched the paper. YL and QH collected the data. AS and YL participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. JW revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA 2009 checklist. (DOC 66 kb)

Additional file 2:

Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS). (DOC 46 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, Yy., Li, Yt., Hu, Ql. et al. Prognostic impact of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in gliomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Onc 17, 152 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1686-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1686-5