Abstract

Background

Schwannomas located in the periportal region are extremely rare. Only 14 cases have been reported in the medical literature worldwide. Cases of porta hepatic schwannomas reported in the literature worldwide were reviewed. As a result, it is very challenging for surgeons to make a preoperative diagnosis due to its rarity and nonspecific imaging manifestations.

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old Chinese female was admitted to our institution with complaint of upper abdominal distension and the abdominal CT in the local hospital revealed a hypodense mass in the porta hepatis. A fine needle aspiration (FNA) was made to confirm the diagnosis, but the result was just suggestive of spindle cell neoplasia. Eventually, the patient underwent surgery and postoperative pathology confirmed schwannoma in porta hepatis. The patient recovered uneventfully with no evidence of recurrence after a follow-up period of 41 months.

Conclusions

It is essential for the final diagnosis of porta hepatic schwannomas to combine histological examination with immunohistochemistry after surgery. The main treatment of porta hepatic schwannomas is complete excision with free margins and no lymph node dissection. In some cases, biliary reconstruction or the proper hepatic and the gastroduodenal artery resection was performed because the tumor was inseparably attached to the extrahepatic bile duct or the proper hepatic and the gastroduodenal artery. Malignant transformation of schwannomas is very rare and the overall prognosis is satisfactory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The periportal region is a complex anatomic region between the superior aspect of the first portion of the duodenum and the porta hepatis, including the hepatoduodenal ligament and the extrahepatic bile duct, portal vein, hepatic artery, autonomic nerve fibers, and lymph nodes [1]. When patients exhibit symptoms of abdominal pain or jaundice or show no symptoms, and a mass in the periportal region is detected in image scans, the diagnosis of a cholangiocarcinoma or a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) may be considered first. However, in rare cases, the diagnosis is of a porta hepatic schwannoma. Porta hepatic schwannomas are extremely rare, with only 14 cases reported in the literature to date. Of the 14 cases, the mean age of the patients was 45 years (range 29–74 years), and the male-female ratio was 6:8. The literature depicted tumors varying from 2.2 cm (the average tumor diameter line) to 7.5 cm in size, with a median of approximately 4.8 cm. For the mass in porta hepatic, it is difficult to perform a biopsy because of vessel interposition. So, the surgeons are inclined to make a fine needle aspiration (FNA) because of lower risk of bleeding. In the 14 cases, the FNA was operated only for two patients, and none underwent biopsy before surgery. But, the FNA usually fails to provide the immunohistochemistry, which is imperative to make a diagnosis for the mesenchymal tumors. In most cases, the final diagnosis of schwannoma was confirmed by postoperative pathological examination.

Herein, we report a case of schwannoma located in the porta hepatis and review cases reported in the literature worldwide for a better understanding of the clinical and pathological features of porta hepatic schwannomas.

Case presentation

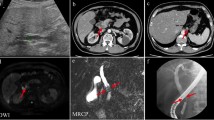

On October 12, 2011, a 57-year-old Chinese female was admitted to our institution with complaint of upper abdominal distension for 2 weeks. She denied any abdominal trauma or surgeries in her life. No specific findings were noted in her family history and personal history. And, she was taking no medications. Before this treatment, she went to the local hospital where an abdominal ultrasound was performed revealing a mass in the head of the pancreas. No abnormalities were detected upon clinical examination and in laboratory investigations. The computer tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1a–c) revealed a 4.0 × 3.2 × 3.0-cm hypodense mass in the porta hepatis, mildly enhanced in arterial phase, and moderately enhanced in portal phase. There was no clear boundary between the mass and the caudate lobe of the liver, and the lower edge of the lesion was close to the neck of pancreas, pressing down on the common hepatic artery. No enlarged hilar lymph nodes or exogenous caudate lobe tumor were identified. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1d–f) showed the long T1 and T2 signal mass in the porta hepatis, with 4.0 × 3.0 cm. The imaging feature on MRI was similar to CT. Fine needle aspiration guided by endoscopic ultrasonography revealed spindle cells arranged in bundles and palisades, with no nuclear atypia, suggestive of a spindle cell neoplasia. With a high suspicion of a GIST, diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. The tumor was located in the porta hepatis, tightly pressing the hepatoduodenal ligament, and the caudate lobe and the pancreas were not involved. Then, after careful dissection, the tumor was found to be in close contact with the common hepatic artery and cystic artery. Subsequently, the patient underwent laparotomy, and intraoperative frozen-section examination revealed a mesenchymal tumor in the porta hepatis, highly suspicious of a GIST. So, the tumor was macroscopically resected en-bloc with the invaded common hepatic artery, and the blood supply of the proper hepatic artery was good through the gastroduodenal artery. And, cholecystectomy was also performed. Post-operative detailed histopathological examination showed benign schwannoma (Fig. 2a–d): CD117(−), S-100(+), GFAP(+), CD34(−), SMA(−), and Ki-67(+, little). Postoperatively, the patient recovered uneventfully. No symptoms or signs of recurrence have been observed in our patient during the 41 months of follow-up.

Abdominal CT and MRI findings of the patient. a Plain CT scan revealed a 4.0 × 3.2 × 3.0-cm hypodense mass in the porta hepatis (black arrow). b Enhanced CT scan revealed a mildly enhanced mass in arterial phase (black arrow). c Moderately enhanced mass in portal phase (black arrow). d MRI revealed a 4.0 × 3.0-cm mass in the sagittal section (black arrow). e Low signal intensity in T1-weighted imaging (black arrow). f High signal intensity in T2-weighted imaging (black arrow)

a Histological examination findings of the tumor: bundles of uniform spindle cells whose elongated nuclei were arranged in a palisading pattern (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification, ×100). b Immunohistochemistry revealed that tumor cells were positive for S-100 protein (magnification, ×100). c Immunohistochemistry revealed that tumor cells were negative for CD117 (magnification, ×100). d Immunohistochemistry revealed that tumor cells were positive for GFAP (magnification, ×100)

Literature review

PubMed, Google scholar (http://scholar.google.com.cn/), the National Knowledge Infrastructure (http://www.cnki.net//), the Chinese periodical Database of Science and Technology (http://lib.cqvip.com/), and the Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform (http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/) were searched for cases of porta hepatic schwannoma between 1985 and 2015, adding up to 14 patients. Details of all the 14 cases and the current case shown in Tables 1 and 2 summarized the important available clinicopathological factors. Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and range.

Discussion

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a tumor derived from Schwann cells, which form the inner portion of the peripheral nerve sheath [2]. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of schwannomas remain unclear, but recent research has indicated that defects in merlin gene are responsible for both sporadic and genetically acquired schwannomas, and the mechanisms by which merlin loss triggers tumor development are being unraveled [3]. Theoretically, the tumor can affect any nerve trunk or any organ, except the olfactory and optic nerves, which lack Schwann cells [4]. The most common locations for schwannomas are the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck, retroperitoneum, mediastinum, pelvis, and peritoneum [5]. Intraperitoneal schwannomas are relatively rare and mostly located in solid organs such as the liver and the pancreas. However, porta hepatic schwannomas are extremely rare, with only 14 cases reported in the literature to date. The sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers are distributed along the hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries, with their branches interwoven into a network, which is the anatomical location of occurrence of the porta hepatic schwannoma [6].

Schwannomas most commonly occur in patients between the ages of 20 and 50 years with equal frequency in men and women [7]. For cases of porta hepatic schwannoma, the mean age of the patients was 48 years (range 29–74 years), and the male-female ratio was 6:9. Symptoms caused by schwannomas vary with the site and size of the tumors. In the 15 cases, the lesion was located in the porta hepatis in nine patients (60 %), hepatoduodenal ligament in five patients (33 %), and proper hepatic artery in one patient (7 %). The literature depicts tumors varying from 2.2 cm (the average tumor diameter line) to 7.5 cm in size, with a median of approximately 4.7 cm. Patients with porta hepatic schwannomas may exhibit symptoms by compressing adjacent structures such as the bile duct and the gastrointestinal tract. In the literature, 40 % of the patients were asymptomatic and 60 % of the patients were symptomatic. The most common symptom was abdominal distension/abdominal discomfort (5/15 patients or 33 %), followed by abdominal pain (4/15 patients or 27 %), jaundice/dark urine/colorless stool/pruritus (2/15 patients or 13 %), nausea/vomiting/anorexia (1/15 patients or 7 %), and weight loss (1/15 patients or 7 %).

Patients with porta hepatic schwannomas usually present with a porta hepatis or hepatoduodenal ligament mass on imaging studies, and it is very challenging for surgeons to make a preoperative diagnosis due to its rarity and nonspecific clinical and imaging characteristics. The ultrasound imaging often shows isoechoic or hypoechoic solid masses with well-defined limits. Generally, a CT scan shows a well-defined hypodense heterogenous mass with peripheral enhancement [8]. Schwannomas on the MRI are usually masses with hypointensity on T1-weighted images and heterogenous hyperintensity or, sometimes internal heterogeneous mixed hypo and hyperintensity on T2-weighted images [9]. Author Cohen has presented histologic evidence suggesting that the hypo-density areas and inhomogeneities in schwannomas are due to hypocellular areas adjacent to more cellular regions and/or hypocellular areas adjacent to dense bundles of collagen, xanthomatous formation, and cystic degeneration within the tumors [10]. In the present case, the CT and MRI showed a homogeneous mass with peripheral enhancement in the porta hepatis. When a solitary, well-demarcated mass occurs in the porta hepatis, differential diagnosis should be made including the following diseases: lymphoma, giant lymph node hyperplasia (GLNH), lymph node tuberculosis, and lesser sac benign smooth muscle tumors such as leiomyomas, nerve sheath tumors, and hemangiomas originating in the lesser sac as well as stromal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract protruding into the lesser sac [11]. Considering that imaging manifestations of porta hepatic schwannomas are nonspecific, patients are usually misdiagnosed preoperatively, unless by biopsy. In the 15 cases, the FNA was operated only for three patients, including the present case. However, the result of FNA may be inconsistent with final pathologic results [12]. Therefore, postoperative pathologic examination is still the gold standard in the diagnosis of schwannoma.

Overall, it is essential for the diagnosis of schwannoma to combine histological examination with immunohistochemistry. Macroscopically, small schwannomas tend to be spheroidal, whereas larger tumors can be sausage-shaped, ovoid, or irregularly lobulated [13]. Larger schwannomas have a tendency to undergo secondary degeneration such as pseudocystic regression, calcification, and hemorrhage [14], which can explain inhomogeneities in a portion of schwannomas. In the 15 cases, seven cases (47 %) underwent cystic changes or calcification. Microscopically, the hallmark of schwannoma is the pattern of alternating Antoni A and B areas, with varying relative amounts [15]. The Antoni A area is hypercellular and characterized by closely packed spindle cells with occasional nuclear palisading and Verocay bodies, whereas the Antoni B area is hypocellular and is occupied by loosely arranged tumor cells [16]. Two kinds of structures often coexist in the same tumor, but most with one main type. There were two cases of cellular schwannoma in 15 cases characterized by predominantly Antoni A areas histologically [17, 18].

Immunohistochemical staining is strongly and diffusely positive for S-100 protein in a schwannoma consistent with the finding of a nerve sheath tumor [10]. A few gastrointestinal stromal tumors are positive for S-100; however, they are also positive for either CD34 or CD117 [19]. As a contrast, a schwannoma is negative for both CD34 and CD117 [20]. A leiomyoma would be negative for S-100 and positive for desmin or smooth muscle actin [19]. In addition, we also demand to make a differential diagnosis with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), although malignant transformation of these tumors is very rare [21]. MPNSTs are usually characterized by high cell density, obvious cell atypia, more pathological mitotic, diverse cellular components, and it is common to see tumor necrosis, CK(+), EMA(+), and CEA(+) [18].

The main treatment of porta hepatic schwannomas is complete excision with free margins and no lymph node dissection. In the 15 cases, seven patients underwent complete tumor excision. But, two patients underwent tumor excision en bloc with hepatic artery resection because of the intraoperative finding of tumor invasion of the hepatic artery (including the present case) [22]. In addition, one patient underwent tumor or bile duct excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy because the tumor was attached to the extrahepatic bile duct [4]. One patient underwent tumor excision en bloc with T-tube drainage because a small rupture of the bile duct wall caused bile leakage during the dissection of the extrahepatic bile duct [17]. One patient underwent tumor excision en bloc with right hepatectomy because the right anterior portal vein was invaded [12], and the details of surgical resection were not specified in three patients. Postoperative pathological results indicated 13 cases of benign schwannoma and two cases of cellular schwannoma which is considered as a subtype of schwannoma [17, 18]. The complete excision of the tumor is curative and most cases do not relapse and additional treatments are not necessary. The overall prognosis is very good [23]. In the follow-up of 6/15 patients, there was no recurrence with a mean follow-up of 16 months (range 3–41 months).

Conclusions

Porta hepatic schwannomas are extremely rare. It is a big challenge to make a correct diagnosis preoperatively due to its rarity and nonspecific imaging and clinical manifestations. Postoperative pathologic examination is still the gold standard in the diagnosis of schwannoma. The main treatment of benign schwannomas is complete excision with free margins and no lymph node dissection and biliary surgery when needed. Malignant transformation of schwannomas is very rare and the overall prognosis is satisfactory after surgery.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Baker ME et al. Computed tomography of masses in periportal/hepatoduodenal ligament. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987;11(2):258–63.

Hajdu SI. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Histogenesis, classification, and prognosis. Cancer. 1993;72(12):3549–52.

Hilton DA, Hanemann CO. Schwannomas and their pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 2014;24(3):205–20.

Kulkarni N et al. Case report: benign porta hepatic schwannoma. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2009;19(3):213–5.

Yu RS, Sun JZ. Pancreatic schwannoma: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31(1):103–5.

Northover JM, Terblanche J. A new look at the arterial supply of the bile duct in man and its surgical implications. Br J Surg. 1979;66(6):379–84.

Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. St. Louis (Mo): Mosby; 2001. p. 1111–207.

Wada Y et al. Schwannoma of the liver: report of two surgical cases. Pathol Int. 1998;48(8):611–7.

Momtahen AJ et al. Liver schwannoma: findings on MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26(10):1442–5.

Cohen LM, Schwartz AM, Rockoff SD. Benign schwannomas: pathologic basis for CT inhomogeneities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147(1):141–3.

Liu YB et al. The CT, MRI features and pathology of portal neurinoma. J Clin Radiol. 2009;28(9):1237–9.

Li B, Jiang TJ. A case report: schwannoma in porta hepatis. Chin Foreign Med Res. 2010;8(7):193–4.

Parizel PM et al. In: De Schepper AM, editor. Tumors of peripheral nerves, in Imaging of soft tissue tumors. New York: Springer; 2001. p. 301–30.

Lee WH et al. Benign schwannoma of the liver: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23(4):727–30.

Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. St. Louis (Mo): Mosby; 2001. p. 1146–67.

Weiss SW, Langloss JM, Enzinger FM. Value of S-100 protein in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors with particular reference to benign and malignant Schwann cell tumors. Lab Invest. 1983;49(3):299–308.

Nagafuchi Y et al. Benign schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: report of a case. Surg Today. 1993;23(1):68–72.

Chen Y, Liu YH. Cellular schwannoma in hepatoduodenal ligament: case report. J Clin Hepatol. 2015;31(2):284–5.

Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466–78.

Fonseca GM et al. Biliary tract schwannoma: a rare cause of obstructive jaundice in a young patient. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(37):5305–8.

Ducatman BS et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer. 1986;57(10):2006–21.

Huang J, Zeng Y, Yan L. Schwannoma originating from the proper hepatic artery. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(8):e15.

Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, editors. Soft tissue tumors. St.Louis: Mosby; 1995. p. 829–42.

Fang WB, Pan YK, Feng ZQ. A case report : schwannoma located behind the common hepatic duct compressing portal vein. Chin J Surg. 1995;08:465.

Huang ZL, Zhou J, Hu LJ. Schwannoma in hepatoduodenal ligament. Chin J Radiol. 1996;04:8.

Choi H et al. Benign schwannoma in the porta hepatis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(3):652.

Park MK et al. A case of benign schwannoma in the porta hepatis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47(2):164–7.

Wang SQ, Yang XQ, Chu CF. Hepatic peripheral nerve sheath tumor: a case report and literature review. J South Univ (Medical Science Edition). 2006;25(2):92–5.

Zhang SX et al. Hepatic pedicle schwannomas: report of two cases. Chin J Radiol. 2009;43(4):444–5.

Pinto J et al. Benign schwannoma of the hepatoduodenal ligament. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E195–6.

Wang KY et al. Schwannoma in porta hepatis: case report. Chin J Gen Surg. 2012;27(1):77.

Wang L, Wang W. Abdominal neurilemmoma: case report. Chin J Med Imaging Technol. 2012;28(7):1267.

Acknowledgements

First of all, I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Sheng-yong Yin, for his instructive advice and useful suggestions on my thesis. I am deeply grateful of his help in the completion of this thesis. I am also deeply indebted to all the other tutors and teachers in Translation Studies for their direct and indirect help to me. Special thanks should go to my friends who have put considerable time and effort into their comments on the draft.

Finally, I am indebted to my parents for their continuous support and encouragement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WDL provided the case and conception. RKW and YYC collected the case data and radiographic images. LXY and WLJ provided the pathological images. LXY made the test of GFAP IHC and provided the photograph. ZZL drafted the manuscript. YSY and ZSS revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, Sy., Zhai, Zl., Ren, Kw. et al. Porta hepatic schwannoma: case report and a 30-year review of the literature yielding 15 cases. World J Surg Onc 14, 103 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0858-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0858-9