Abstract

Breast carcinoma rarely occurs in cases of foreign body granulomas following liquid silicone injection. Although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned the use of all silicone injection products in 1992, liquid silicone injection for breast augmentation continues to be performed illegally. We herein report a case of breast carcinoma following liquid silicone injection in a 67-year-old female.

A total of 45 years after liquid silicone injection, the patient had felt a breast mass in the right breast. Mammography showed a smooth mass that retracted the right nipple. Due to the presence of a marked acoustic shadow caused by the granulomas, evaluating the mass on ultrasonography was difficult. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a lobulated mass under the right nipple. The mass exhibited low signal intensity (SI) on T1-weighted images and intermingled high and low SI on T2-weighted images. Heterogeneous early enhancement with central low intensity was noted on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Several oval-shaped low SI structures in the adipose tissue and disruption of the pectoralis major muscle were also observed. We diagnosed the patient with invasive ductal carcinoma based on a stereotactic-guided Mammotome® (a vacuum-assisted biopsy system manufactured by DEVICOR MEDICAL JAPAN, Tokyo, Japan) biopsy and subsequently performed mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection (with a positive result for the sentinel node biopsy). Histologically, invasive ductal carcinoma was observed in the silicone granuloma.

The development of foreign body granulomas following breast augmentation usually makes it difficult to detect breast cancer; thus, various devices are required to confirm the histological diagnosis of breast lesions. The stereotactic-guided Mammotome® biopsy system may be an effective device for diagnosing breast cancer developing in the augmented breast.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Liquid silicone injection for breast augmentation was initiated worldwide and in Japan in the 1940s [1,2]. However, due to complications such as inflammatory changes and fibrosis, the use of liquid silicone for breast augmentation has been decreasing [3,4]. In August 1991, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited the marketing or sale of injectable liquid silicone for esthetic purposes [5]. Notably, the FDA has never approved the use of injections of liquid silicone for cosmetic treatment in patients. In 1992, the FDA officially banned the use of all silicone injection products in medical procedures. However, liquid silicone injection for breast augmentation continues to be performed illegally, making it difficult to estimate the number of females who have received this procedure [3,4,6]. We herein report a case of breast carcinoma following liquid silicone injection in a 67-year-old female.

Case presentation

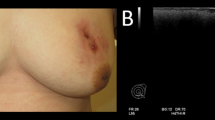

A 67-year-old female felt a breast mass in her right breast and visited our hospital. She had received silicone oil injection into bilateral breasts at 22 years of age. Mammography showed a smooth mass that retracted the right nipple (Figure 1a). Ultrasonography revealed a so-called ‘snowstorm’ appearance with diffuse hyperechogenic lesions and posterior shadowing (Figure 1b). It was difficult to distinguish between the silicone granuloma and breast cancer using these modalities; therefore, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. T1-weighted images showed a low signal intensity (SI) mass (3.5 × 3.2 × 4.0 cm in size) that retracted the right nipple (Figure 2a). Several oval-shaped low SI structures in the adipose tissue and disruption of the pectoralis major muscle were also observed (Figure 2a). The mass showed intermingled high and low SI on T2-weighted images (Figure 2b), while heterogeneous early enhancement with central low intensity was noted on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (Figure 2c,d). On diffusion-weighted images, the mass exhibited high SI due to the restricted diffusion.

Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (a) T1-weighted MRI showed a low signal intensity (SI) mass (3.5 × 3.2 × 4.0 cm in size) that retracted the right nipple. Several oval-shaped low SI structures in adipose tissue and disruption of the pectoralis major muscle were also observed (arrows). (b) The mass showed intermingled high and low SI on T2-weighted images. (c, d) Heterogeneous early enhancement with central low intensity was noted on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (c: early phase, d: delay phase).

We investigated available approaches for diagnosing this tumor histologically and consequently performed a stereotactic-guided Mammotome® (a vacuum-assisted biopsy system manufactured by DEVICOR MEDICAL JAPAN, Tokyo, Japan) biopsy because the tumor was clearly detectable on mammography. The most high-density area of the tumor was targeted in order to obtain tissue samples from the tumor. According to the histological findings of the biopsied specimens, we diagnosed the patient with invasive ductal carcinoma and subsequently performed mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection (with a positive result for the sentinel node biopsy). The intraoperative findings showed marked adipose degeneration in the retromammary space and many white round bodies, which indicated the presence of capsulated silicone (Figure 3). The resected specimens demonstrated a white and partially red lobulated mass (3.4 × 2.7 cm in size) (Figure 4a).

Resected specimens and histological findings. (a) The resected specimens showed a white and partially red lobulated mass (arrows). (b, c) Histologically, stromal invasion of invasive ductal carcinoma was observed in the silicon granuloma (hematoxylin & eosin [HE] stain; b: HE stain X4, c: HE stain X100). (d) Inflammatory granulomas and foreign body giant cells (arrows) were observed (HE stain X100).

Histologically, stromal invasion of invasive ductal carcinoma was observed in the silicone granuloma (Figure 4b,c), and inflammatory granulomas and foreign body giant cells were also observed (Figure 4d). The pathological diagnosis was as follows: scirrhous carcinoma, nuclear grade 3, positive for lymph node metastasis (1/18), estrogen receptor-positive (95%), progesterone receptor-positive (30%), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative (score 1+ on immunohistochemistry), and a high Ki-67 index (35%). Four cycles of treatment with EC (90 mg/m2 of epirubicin and 600 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide) were given as adjuvant chemotherapy, and the patient currently remains alive, without recurrence, at 10 months after the surgery.

Discussion

As a result of liquid silicone injection to the breast, many females develop inflammatory changes and granulomas, which complicate breast cancer screening [7]. Mammography in these patients often shows numerous bilateral round or oval masses with rim calcification, while ultrasonography shows a ‘snowstorm’ appearance with diffuse hyperechogenic lesions and posterior shadowing characteristic of free silicone, ring-down artifacts [8,9]. These radiographic findings make it difficult to detect breast cancer in the early stage; thus, contrast-enhanced MRI is beneficial for breast cancer screening [10,11]. Many cases of breast carcinoma developing in the augmented breast have been reported to date [6,10-23]. Major cohort studies investigating the frequency of breast cancer following breast augmentation have reported rates ranging from 0.2% to 2.7% [24]. We herein reported a case of breast carcinoma that developed in the augmented breast following liquid silicon injection. Histologically, inflammatory granulomas and foreign body giant cells were observed with stromal invasion of invasive ductal carcinoma. Various histological types of cancer have been reported after liquid silicone injection in the previous literature [6,12,15,17,18,20-23]. Interestingly, there are two cases of squamous cell carcinoma following liquid silicone injection [15,17]. Handel et al. mentioned that augmented patients present with a statistically greater frequency of palpable lesions, with a slightly greater risk of invasive tumors and an increased likelihood of axillary lymph node metastases [13]. Despite this observation, there are no statistically significant differences in the stage at diagnosis or the prognosis between augmented and non-augmented patients [13,19]. However, most of the augmented patients in these studies received a bag prosthesis or paraffin injection. Therefore, the details of the histological and clinical characteristics of breast cancer following liquid silicone injection have not been thoroughly investigated to date.

Performing the accurate detection and evaluation of breast carcinoma in cases of foreign body granulomas is difficult, as the images are severely affected by artifacts caused by the granulomas. Therefore, various devices are required to confirm the histological diagnosis of breast cancer. In the present study, we performed a stereotactic-guided Mammotome® biopsy because the tumor was detectable on a mammogram in this case. Importantly, the early diagnosis of breast cancer resulted in successful curative surgery and subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy. The stereotactic-guided Mammotome® biopsy system may be an effective device for diagnosing breast cancer developing in the augmented breast.

Conclusions

In conclusion, obtaining an early diagnosis of breast carcinoma originating from silicone granulomas is difficult. The stereotactic-guided Mammotome® biopsy system may be an effective device for diagnosing breast cancer developing in the augmented breast.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent form is available for review from the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- SI:

-

signal intensity

- DWI:

-

diffusion-weighted images

- HER2:

-

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HE stain:

-

hematoxylin & eosin stain

References

Mastruserio DN, Pesqueira MJ, Cobb MW. Severe granulomatous reaction and facial ulceration occurring after subcutaneous silicone injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(5):849–52.

Duffy DM. Injectable liquid silicone: new perspectives. In: Klein AW, editor. Tissue Augmentation in Clinical Practice. 1st ed. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc; 1998. p. 237–27.

Steinbach BG, Hardt NA, Abbitt PL. Mammography: breast implants − types, complications, and adjacent breast pathology. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 1993;22:39–86.

Steinbach BG, Hardt NS, Abbitt PL, Lanier L, Caffee HH. Breast implants, common complications, and concurrent breast disease. Radiographics. 1993;13:95–118.

Food and Drug Administration. Current and useful information on collagen and liquid silicone injections. FDA Backgrounder. BG91-20th ed. 1991.

Cheung YC, Lee KF, Ng SH, Chan SC, Wong AM. Sonographic feature s with histologic correlation in two cases of palpable breast cancer after breast augmentation by liquid silicone injection. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30:548–51.

Peters W, Fornasier V. Complications from injectable materials used for breast augmentation. Can J Plast Surg. 2009;17(3):89–96.

Erguvan-Dogan B, Yang WT. Direct injection of paraffin into the breast: mammographic, sonographic, and MRI features of early complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(3):888–94.

Scaranelo AM, De Fátima Ribeiro Maia M. Sonographic and mammographic findings of breast liquid silicone injection. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34(6):273–7.

Kang BJ, Kim SH, Choi JJ, Lee JH, Cha ES, Kim HS, et al. The clinical and imaging characteristics of breast cancers in patients with interstitial mammoplasty. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(6):1029–35.

Youk JH, Son EJ, Kim EK, Kim JA, Kim MJ, Kwak JY, et al. Diagnosis of breast cancer at dynamic MRI in patients with breast augmentation by paraffin or silicone injection. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(12):1175–80.

Tanaka Y, Morishima I, Kikuchi K. Invasive micropapillary carcinomas arising 42 years after augmentation mammoplasty: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:33.

Handel N, Silverstein MJ. Breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis in augmented women. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3):587–93. discussion 594-6.

Peng HL, Wu CC, Choi WM, Hui MS, Lu TN, Chen LK. Breast cancer detection using magnetic resonance imaging in breasts injected with liquid silicone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(7):2116–20.

Smith LF, Smith TT, Yeary E, McGee JM, Malnar K. Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast following silicone injection of the breasts. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1999;92(3):126–30.

Noh DY, Yun IJ, Kang HS, Kim YC, Kim JS, Chung JK, et al. Detection of cancer in augmented breasts by positron emission tomography. Eur J Surg. 1999;165(9):847–51.

Talmor M, Rothaus KO, Shannahan E, Cortese AF, Hoffman LA. Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast after augmentation with liquid silicone injection. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34(6):619–23.

Maddox A, Schoenfeld A, Sinnett HD, Shousha S. Breast carcinoma of the breast occurring in association with silicone augmentation. Histopathology. 1993;23(4):379–82.

Clark 3rd CP, Peters GN, O’Brien KM. Cancer in the augmented breast diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer. 1993;72(7):2170–4.

Bingham HG, Copeland EM, Hackett R, Caffee HH. Breast cancer in a patient with silicone breast implants after 13 years. Ann Plast Surg. 1988;20(3):236–7.

Timberlake GA, Looney GR. Adenocarcinoma of the breast associated with silicone injections. J Surg Oncol. 1986;32(2):79–81.

Pennisi VR. Obscure carcinoma encountered in subcutaneous mastectomy in silicone- and paraffin-injected breasts: two patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74(4):535–8.

Lewis CM. Inflammatory carcinoma of the breast following silicone injections. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66(1):134–6.

Stivala A, Libra M, Stivala F, Perrotta R. Breast cancer risk in women treated with augmentation mammoplasty (review). Oncol Rep. 2012;28(1):3–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Teruhiko Fujii (Department of Research Center for Innovative Cancer Therapy, Kurume University School of Medicine, Kurume, Japan) for revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. The authors declare that they had no funding sources for this case study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RN and RT acquired the data and drafted the manuscript. MA, KT, and SH participated in designing the study. RNM evaluated the radiological images and critically revised the manuscript. SM evaluated the pathological findings. SN and YA supervised the design of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakahori, R., Takahashi, R., Akashi, M. et al. Breast carcinoma originating from a silicone granuloma: a case report. World J Surg Onc 13, 72 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0509-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0509-6