Abstract

Background

Nutrition care can positively affect multiple aspects of patient’s health; outcomes are commonly evaluated on the basis of their impact on a patient’s (i) illness-specific conditions and (ii) health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Our systematic review examined how HRQoL was measured in studies of nutritional interventions. To help future researchers select appropriate Quality of Life Questionnaires (QoLQ), we identified commonly-used instruments and their uses across populations in different regions, of different ages, and with different diseases.

Methods

We searched EMCare, EMBASE, and Medline databases for studies that had HRQoL and nutrition intervention terms in the title, the abstract, or the MeSH term classifications “quality of life” and any of “nutrition therapy”, “diet therapy”, or “dietary supplements” and identified 1,113 studies for possible inclusion.We then reviewed titles, abstracts, and full texts to identify studies for final inclusion.

Results

Our review of titles, abstracts, and full texts resulted in the inclusion of 116 relevant studies in our final analysis. Our review identified 14 general and 25 disease-specific QoLQ. The most-used general QoLQ were the Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey (SF-36) in 27 studies and EuroQol 5-Dimension, (EQ-5D) in 26 studies. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ), a cancer-specific QoLQ, was the most frequently used disease-specific QoLQ (28 studies). Disease-specific QoLQ were also identified for nutrition-related diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and dysphagia. Sixteen studies used multiple QoLQ, of which eight studies included both general and disease-specific measures of HRQoL. The most studied diseases were cancer (36 studies) and malnutrition (24 studies). There were few studies focused on specific age-group populations, with only 38 studies (33%) focused on adults 65 years and older and only 4 studies focused on pediatric patients. Regional variation in QoLQ use was observed, with EQ-5D used more frequently in Europe and SF-36 more commonly used in North America.

Conclusions

Use of QoLQ to measure HRQoL is well established in the literature; both general and disease-specific instruments are now available for use. We advise further studies to examine potential benefits of using both general and disease-specific QoLQ to better understand the impact of nutritional interventions on HRQoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nutrition interventions play a crucial role in the management of a wide range of physiological and pathological conditions. The link between proper nutrition and good health status has been transformed from a scientific research field to a focal point in institutions and governments. For example, the Rockefeller Foundation and the American Heart Association have created the Food is Medicine Research Initiative, with a goal to support and promote nutrition as a preventive tool and as part of the treatment for various conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, renal diseases, arthritis, mental health, and neurological disorders [1]. Additionally, evidence from numerous studies supports the effectiveness of nutrition therapy in the management of diabetes [2, 3]. A healthy diet and moderate physical activity can reduce the risk of developing diabetes by 58% [4]. Research has also shown that nutritional supplements and dietary interventions can reduce the risks of negative cardiovascular outcomes [5, 6].

Nutrition interventions are crucial for improving the nutritional status of an individual who is malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. Malnutrition has been linked to reduced immune function, increased infection rates, prolonged hospitalization, high medical expenditure, and increased mortality rates [7]. Disease-related malnutrition is prevalent in conditions such as cancer, with a prevalence ranging from 50–80% due to disease-related anorexia and various symptoms associated with both the disease and its treatment [8]. Studies across multiple populations have shown the positive impact of improving nutritional status on an individual’s overall health [9, 10]. Because of their potential to impact multiple aspects of patient health, nutrition interventions should not only be evaluated based on their impact on specific illnesses, but also on their effect on the individual's health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Quality of life (QoL) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns [11]. It is affected in complex ways by the person's physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, and how the person relates to key features of their environment. Given the complexity of the concept, the assessment of QoL is challenging and requires multiple measures to capture subjectivity and multidimensionality [12]. Various instruments have been developed to measure the above domains, but none are recognized as the "gold standard" [13]. Quality of Life Questionnaires (QoLQ) are extensively employed as HRQoL instruments in clinical or experimental contexts and they can be used to determine the patient-self-perceived health state and/or as part of a cost-effectiveness analyses for health economic evaluation [14].

QoLQ can be either general for several conditions or disease-specific - designed and validated for the assessment of QoL in specific populations. General QoLQ facilitate QoL measurement across diseases and interventions and enable policy evaluation. Disease-specific QoLQ instruments allow researchers to evaluate changes in health-related QoL aspects of a particular illness. The choice of instrument is often based on factors such as the purpose of the study, the studied population, available resources, and subsequent data handling [13].

Nutrition has the potential to enhance individual’s QoL, and therefore, should be assessed in nutrition interventions. However, the selection of QoLQ can be complex, considering the variety of study characteristics and the lack of guidelines or consensus on the most suitable tools to be used in nutrition interventions. This systematic review summarizes the available evidence about the use of QoLQ in the context of nutrition interventions based on its characteristics across different populations, diseases, and regions with the objective to shed light on the choice of QoLQ in future nutrition research.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic review of the literature was conducted of studies evaluating the impact of nutritional interventions on QoL. Articles were identified by searching the EMCare, EMBASE, and Medline databases. The search strategy identified articles that included “Quality of Life” and “nutrition intervention” terms in the title or abstract or were classified by the MeSH terms “quality of life" and any of “nutrition therapy”, “diet therapy”, or “dietary supplements”. See Supplemental Fig. 1 (see Additional file 1) for complete Boolean logic used to search all databases. Articles in English published up to September 2022 in journal articles reporting on randomized controlled trials, multicenter studies, clinical trials, comparative studies, observational studies, and case reports were included. In addition to the electronic search, a manual search of review articles was conducted, resulting in the addition of seven articles. An additional four trials were identified through cost-effectiveness studies based on original trials captured in our search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were considered eligible for inclusion if they used a validated measure of patient QoL (patient reported or other) or were part of an initiative to develop or validate a QoL measure. Additionally, the primary study intervention needed to be a nutrition intervention, where nutrition intervention was broadly defined to include oral nutritional supplements, nutrition education or counseling, enteral nutrition, parenteral nutrition, or other activities to improve the nutrition consumed by study patients [15]. Studies in which the nutritional intervention was part of a broader quality improvement program or protocol shift that included a change in nutrition care, such as an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol with a nutrition component, were included. Studies were excluded if the primary study intervention was not nutrition or nutrition-related, or if the study used a QoL measure that is not accepted by the scientific community or QoLQ instruments that were not validated. All studies identified by the initial search were reviewed by the authors to determine if the study fully met inclusion criteria. Study titles and abstracts were assessed by all authors to identify relevant studies, with studies not meeting inclusion criteria eliminated. Full text of the remaining studies was reviewed to determine if inclusion criteria were met. Disagreements on inclusion or exclusion were resolved by group discussion and consensus.

Data collection

Data was collected by the group on each study, reviewing the full text to identify nutrition intervention, QoL instrument used, patient population, and medical condition or pathology addressed by the intervention. Information from each study was input to a custom Excel spreadsheet developed by the authors. Questionnaires were classified by whether they measured QoL in a general or specific population. A questionnaire was classified as measuring QoL in a specific population if its intended use was limited to a group identified by age, sex, or medical condition, whereas general questionnaires could be used regardless of patient age, sex, or medical condition. For population-specific questionnaires, the target population was recorded. We also collected data on the locations where nutrition intervention studies using QoLQ were conducted.

Collected data are summarized in Supplemental Materials Table 1 (see Additional file 1).

Results

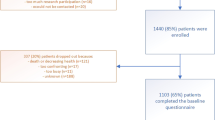

Results from the authors’ review are summarized in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1). Our initial search yielded 1,102 studies. Review of titles, abstracts and full-text resulted in 116 studies being included in our analysis. A total of 39 QoLQ were identified in the 116 included studies. 72 studies used a general (62%) and 52 used a disease-specific or population-specific QoLQ (45%). We identified 14 general QoLQ, and 25 disease- or population-specific QoLQ; 10 of the disease-specific QoLQ focused on various types of cancer. Summary of all questionnaires identified, classified, and briefly described can be found in Table 1.

Of the 14 general QoLQs identified in our search, a large difference in the frequency of use among them was detected, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The Short Form series questionnaires (SF series including SF-36 and SF-12) were the most frequently used questionnaires, appearing in 30 studies. The EQ-5D questionnaires, including EQ-5D-3L and EQ- 5D-5L (also one study used part of the questionnaire, the EQ-5D-VAS), were used in 26 studies and were the second most frequently used general questionnaire.

When examining the 25 disease-specific QoLQ, we found that a wide range of tools designed for specific pathologies, but cancer was the only disease with multiple disease-specific QoLQ and was the focus of our analysis of these instruments. To better understand the different tools used to assess QoL in cancer, Fig. 3 shows all the cancer-related QoLQ and their frequency of use in the nutrition intervention studies analyzed. The EORTC family of questionnaires (including EORTC-QLQ-C30, EORTC-QLQ-OES18, EORTC-QLQ-BR23, EORTC-QLQ-H&N35 and EORTC-QLQ-PAN26) were the most frequently used cancer-specific QoLQ, appearing in 28 studies.

Although most studies used only one QoLQ, 16 studies used multiple QoLQ. Six studies combined a general QoLQ with a disease-specific QoLQ. Eight studies used two disease-specific (cancer) QoLQ. One study used two general QoLQs, the SF-36 and EQ-5D, to assess QoL. Finally, we identified a study that used 3 questionnaires, 2 disease-specific, and 1 general QoLQ, to assess QoL during the intervention.

Many pathologies were being treated in the nutrition interventions using QoLQ included. Cancer was the most frequently studied condition, followed by malnutrition. To determine whether there was a trend in the use of disease-specific and/or general questionnaires based on the pathology, we categorized the questionnaires used in the most prevalent pathologies. The relative frequency (%) of each group of QoLQ usage based on the pathology can be seen in Fig. 4. As observed, only in studies related to cancer was the use of disease-specific QoLQ is more widespread than general QoLQ, despite availability of disease-specific questionnaires for all the analyzed pathologies.

Next, we analyzed which questionnaires were used for each pathology: fifteen different QoLQ were used in the 36 cancer-related studies included in our review. Thirty-two (88%) of these studies included at least one cancer-specific QoLQ. Conversely, malnutrition studies mostly used general QoLQ, such as EQ-5D and SF-36. Studies focusing on overweight used SF-36 more often than a disease-specific questionnaire (e.g., IWQOL-Lite). Table 2 shows the most frequently studied pathologies within the papers included in our review, the QoLQ used in each, and the number of studies where the QoLQ mentioned was used.

We also examined the use of QoLQ in specific populations. Most of the studies were carried out in adult populations, with only four studies (3% of the total) focused on pediatric populations. The PedsQL questionnaire, exclusively designed for the pediatric population appeared only in 2 studies despite being an established instrument for measuring QoL in pediatric research. Research in older adults was also limited, finding only 38 studies (33% out of total) carried out in population older than 65 years. Malnutrition was the pathology most frequently studied in this population. Table 3 summarizes the pathologies and QoLQ in these age-specific populations.

Finally, we evaluated the regions in which QoLQ were used. Regions were categorized as developed or developing economies following the UN2020 Classification of Developed Countries [170]. Twenty-nine studies using a general QoL were conducted in Europe (40% of the total studies using general QoLQ), followed by sixteen studies conducted in Developed Asia and Pacific (22%), twelve in Asia (17%), ten in North America (14%), and five in Latin America (7%). In Europe, the EQ-5D questionnaires were the most frequently used (20 studies) followed by the SF-36 (8 studies). In the Developed Asia Pacific region, SF questionnaires were the most used (6 studies), closely followed by the three versions of the AQoL questionnaire (4 studies) and the EQ-5D (4 studies). In Asia and North America, the SF questionnaires were most frequently used (8 and 7 respectively). Figure 5 summarizes the use of general QoLQ and number of studies that appeared in each region.

Half of studies using cancer-specific QoLQ were conducted in Asia (12 studies), followed by ten in Europe (32% out of total), two in North America (6%), two in Developed Asia and Pacific (6%), one in Latin America (3%) and one in Africa (3%). The EORTC series was the most frequently used questionnaire globally, with a high percentage of use in Asia and Europe. In contrast, North America used the FACT series of questionnaires in all the identified studies related with cancer. Figure 6 summarizes the use of cancer QoLQ and number of studies that appeared in each region.

Discussion

Our review identified 14 general and 25 disease-specific QoLQ. The most-used QoLQ were the SF-36, EQ-5D and EORTC-QLQ. Commonly studied diseases were cancer and malnutrition. Only 33% of the studies focused on adults 65 years and older. Regional variation in QoLQ use was observed, with EQ-5D used more frequently in Europe and SF-36 more commonly used in North America.

Results of our systematic review found significant variation in use of QoLQ instruments for nutrition interventions. General questionnaires were widely utilized across various pathologies, age groups, and geographical locations, with the SF series and EQ-5D being the most prevalent. This finding is consistent with previous research by Haraldstad et al. [171]. Both instruments are short and contain simple, straightforward question items. Both are readily available in a variety of languages, and can be either self-administrated or by interview. This facilitates their use in nutrition interventions regardless of population characteristics. However, their simplicity may hinder capturing aspects of quality of life that are significant in specific population groups [172].

Among disease-specific questionnaires, a variety of instruments were also found. Cancer-specific QoLQ were widely used, and we identified several tools for assessing QoL in patients with cancer; EORTC-QLQ series, one of those Cancer-QoLQ, was the questionnaire most use among disease-specific QoLQ. In contrast, other pathologies were found to be assessed typically by general QoLQ, even though it has been reported that general QoLQ may be less sensitive to changes in disease or treatment compared to disease-specific instruments in several pathologies [173]. For example, the FACT-C questionnaire for patients with colorectal cancer includes questions about digestion, stomach cramping and the impact of an ostomy appliance [137]. This enables researchers to examine the ways an intervention may change how patients experience treatment and illness in greater depth than questionnaires focusing on general functionality and overall health. Additionally, disease-specific QoLQ may examine QoL domains not included in general QoLQ. For example, the EQ-5D, a general QoLQ, uses mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression domains whereas the IWQOL-Lite, a QoLQ assessing the impact of weight on adult QoL, assesses the domains of physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress, and work. It is highly recommendable that researchers evaluate disease-specific QoLQ available to them and include such questionnaires as appropriate.

Given the additional information provided by disease-specific QoLQ, we were surprised that only eight studies used both general and disease-specific questionnaires. The use of these two types together has been recommended previously and yielded interesting results [174]. As a case in point, Ard et al. found that a nutrition intervention improved overall QoL as measured by the SF-36, as well as self-esteem as measured by the IWQOL [17]. Although additional information may be beneficial for a study, resources in any study are at a premium and the use of multiple QoLQ may challenge study budgets, while increasing the amount of time required for patients to participate in the study. Researchers should balance these costs against the potential benefits of better understanding how interventions impact patients’ lives and experiences.

This review also shows that QoLQs have been used to study the impact of nutrition interventions on quality of life of patients with a variety of illnesses. In particular, we found that studies of nutrition interventions and QoL focused heavily on cancer and malnutrition. This is not surprising since previous studies have reported the importance of evaluating QoL when determining nutritional status to tailor the nutritional intervention to the specific individual requirements of cancer [175] and malnourished patients [176]. Fewer studies examined nutrition interventions and QoL in patients with other illnesses such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease, even though the evidence shows a link between nutrition and QoL in patients with these pathologies [177, 178]. This suggests an opportunity for future research to expand the use of QoLQ in nutrition intervention studies, particularly in these diseases where nutrition interventions may have a significant impact on QoL.

Another focus of our study was nutrition interventions in specific age groups, especially in older adults, where nutrition interventions may be particularly impactful on their QoL [13, 179]. The aging process reduces appetite and individuals’ ability to ingest sufficient food to meet nutritional requirements, reducing physical and cognitive function, and QoL [9, 180,181,182]. Nutrition interventions assist older individuals in meeting nutritional requirements, maintaining physical and cognitive function, key components of QoL. However, we identified few studies focusing on this population, consistent with Arensberg et al. findings [183]. The absence or exclusion of older adults from clinical trials restricts data availability, forcing clinicians to make treatment decisions for older adults without adequate guidance [184]. For instance, only 4% of participants in cancer clinical trials conducted between 2005 and 2015 were aged over 80, whereas around 16% of individuals aged 80 or older in 2013 were diagnosed with cancer [185].

Promoting independence and healthy aging in a growing elderly population presents several key challenges. These include assessing the significance of factors such as nutrition in enhancing quality of life, developing effective interventions through research, and translating these findings into policies for implementation [183]. Future studies of nutrition interventions should focus on elderly populations and include QoL as an endpoint.

We also identify significant regional variation in QoLQ usage. EQ-5D questionnaires are more frequently used in Europe while the SF family of questionnaires are more commonly used in North America. The cause of this variation is beyond the scope of this project; however, it highlights the need for researchers and professional societies to develop harmonized guidelines for use of QoLQ in nutrition intervention studies. Such efforts would facilitate the comparison of nutrition interventions’ impact on QoL across studies.

Conclusions

This review examined 116 articles that utilized QoLQ to ascertain how quality of life was measured in studies of nutritional intervention. We identified 39 different instruments used in studies from all parts of the world. Use of QoLQ to measure HRQoL is well established in the literature, with both general and disease-specific instruments being employed, but there is not a single dominant questionnaire in use. Instead, HRQoL instrument choice appears to be driven by the location in which the study takes place and the patient population being studied. Future researchers should consider these factors when selecting of a QoLQ for future nutritional intervention studies to facilitate comparability of results across studies. We also encourage researchers and professional societies to develop harmonized guidelines for use of QoL instruments for nutritional intervention studies with the aim to better understand the value and impact of nutrition interventions on quality of life of patients across different disease states and across different care settings.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the authors.

Abbreviations

- AQoL:

-

Assessment of Quality of Life

- EORTC:

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQol 5 dimensions; refers to a set of quality of life questionnaires. See Table 1

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IWQOL:

-

Impact of Weight on QoL refers to a quality of life questionnaire. See Table 1

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- PedsQL:

-

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- QoL:

-

Quality of Life

- QoLQ:

-

Quality of Life Questionnaire

- SF-36:

-

Short-form, 36 questions; refers to a set of quality of life questionnaires. See Table 1.

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Downer S CE, Kummer C. Food is Medicine Research Action Plan. Food & Society Aspen Institute. 2022.

Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):541–51.

Quimby KR, Murphy MM, Harewood H, Howitt C, Hambleton I, Jeyaseelan SM, et al. Adaptation of a community-based type-2 diabetes mellitus remission intervention during COVID-19: empowering persons living with diabetes to take control. Implement Sci Commun. 2022;3(1):5.

Pastors JG, Warshaw H, Daly A, Franz M, Kulkarni K. The evidence for the effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy in diabetes management. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):608–13.

Khan SU, Khan MU, Riaz H, Valavoor S, Zhao D, Vaughan L, et al. Effects of nutritional supplements and dietary interventions on cardiovascular outcomes: an umbrella review and evidence map. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(3):190–8.

Delgado-Lista J, Alcala-Diaz JF, Torres-Peña JD, Quintana-Navarro GM, Fuentes F, Garcia-Rios A, et al. Long-term secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet and a low-fat diet (CORDIOPREV): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10338):1876–85.

Saunders J, Smith T. Malnutrition: causes and consequences. Clin Med (Lond). 2010;10(6):624–7.

Lis CG, Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Markman M, Vashi PG. Role of nutritional status in predicting quality of life outcomes in cancer – a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2012;11(1):27.

Kaur D, Rasane P, Singh J, Kaur S, Kumar V, Mahato DK, et al. Nutritional interventions for elderly and considerations for the development of geriatric foods. Curr Aging Sci. 2019;12(1):15–27.

Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M, Babio N, Martínez-González MÁ, Ibarrola-Jurado N, Basora J, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;34(1):14–9.

Organization WH. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(12):1569–85.

Campolina AG, Dini PS, Ciconelli RM. Impacto da doença crônica na qualidade de vida de idosos da comunidade em São Paulo (SP, Brasil). Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2011;16(6):2919–25.

Amarantos E, Martinez A, Dwyer J. Nutrition and quality of Life in older adults. J Gerontol Series A. 2001;56(suppl_2):54–64.

Makai P, Brouwer WBF, Koopmanschap MA, Stolk EA, Nieboer AP. Quality of life instruments for economic evaluations in health and social care for older people: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:83–93.

Anghel S, Kerr KW, Valladares AF, Kilgore KM, Sulo S. Identifying patients with malnutrition and improving use of nutrition interventions: a quality study in four US hospitals. Nutrition. 2021;91–92: 111360.

Hooker SA. SF-36. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR, editors. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Springer, New York: New York, NY; 2013. p. 1784–6.

Ard JD, Gower B, Hunter G, Ritchie CS, Roth DL, Goss A, et al. Effects of calorie restriction in obese older adults: the CROSSROADS randomized controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2016;73(1):73–80.

de García Pérez Sevilla G, Barceló Guido O, De la Cruz MDlP, Blanco Fernández A, Alejo LB, Montero Martínez M, et al. Adherence to a lifestyle exercise and nutrition intervention in University Employees during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7510.

Lu L, Chen X, Lu P, Wu J, Chen Y, Ren T, et al. Analysis of the effect of exercise combined with diet intervention on postoperative quality of life of breast cancer patients. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:4072832.

Gomi A, Yamaji K, Watanabe O, Yoshioka M, Miyazaki K, Iwama Y, et al. Bifidobacterium bifidum YIT 10347 fermented milk exerts beneficial effects on gastrointestinal discomfort and symptoms in healthy adults: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101(6):4830–41.

Towery P, Guffey JS, Doerflein C, Stroup K, Saucedo S, Taylor J. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and function improve with a plant-based diet. Complement Ther Med. 2018;40:64–9.

Hagberg L, Winkvist A, Brekke HK, Bertz F, Hellebö Johansson E, Huseinovic E. Cost-effectiveness and quality of life of a diet intervention postpartum: 2-year results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):38.

Brain K, Burrows TL, Rollo ME, Hayes C, Hodson FJ, Collins CE. The effect of a pilot dietary intervention on pain outcomes in patients attending a tertiary pain service. Nutrients. 2019;11(1):181.

von Berens Å, Fielding RA, Gustafsson T, Kirn D, Laussen J, Nydahl M, et al. Effect of exercise and nutritional supplementation on health-related quality of life and mood in older adults: the VIVE2 randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):286.

Zhang H, Qiu Y, Zhang J, Ma Z, Amoah AN, Cao Y, et al. The effect of oral nutritional supplements on the nutritional status of community elderly people with malnutrition or risk of malnutrition. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2021;30(3):415–23.

Kwon J, Yoshida Y, Yoshida H, Kim H, Suzuki T, Lee Y. Effects of a combined physical training and nutrition intervention on physical performance and health-related quality of life in prefrail older women living in the community: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(3):263.e1-.e8.

Matthews J, Torres SJ, Milte CM, Hopkins I, Kukuljan S, Nowson CA, et al. Effects of a multicomponent exercise program combined with calcium–vitamin D3-enriched milk on health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in older men: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59(3):1081–91.

Li H, Li H, Feng S, Li Z, Tian X, Wei Y, editors. Effects of overall enteral nutrition management overall on nutritional condition and life quality of NSCLC patients treated by apatinib combined with chemoradiotherapy. 2020.

Folope V, Meret C, Castres I, Tourny C, Houivet E, Grigioni S, et al. Evaluation of a supervised adapted physical activity program associated or not with oral supplementation with arginine and leucine in subjects with obesity and metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2022;14(18):3708.

Sammarco R, Marra M, Di Guglielmo ML, Naccarato M, Contaldo F, Poggiogalle E, et al. Evaluation of hypocaloric diet with protein supplementation in middle-aged Sarcopenic obese women: a pilot study. Obes Facts. 2017;10(3):160–7.

Khammassi M, Miguet M, O’Malley G, Fillon A, Masurier J, Damaso AR, et al. Health-related quality of life and perceived health status of adolescents with obesity are improved by a 10-month multidisciplinary intervention. Physiol Behav. 2019;210:112549.

Bo Y, Liu C, Ji Z, Yang R, An Q, Zhang X, et al. A high whey protein, vitamin D and E supplement preserves muscle mass, strength, and quality of life in Sarcopenic older adults: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):159–64.

Li C, Carli F, Lee L, Charlebois P, Stein B, Liberman AS, et al. Impact of a trimodal prehabilitation program on functional recovery after colorectal cancer surgery: a pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(4):1072–82.

Prasada S, Rambarat C, Winchester D, Park K. Implementation and impact of home-based cardiac rehabilitation in a Veterans affair medical center. Mil Med. 2019;185(5–6):e859–63.

Lindqvist HM, Gjertsson I, Eneljung T, Winkvist A. Influence of Blue Mussel (Mytilus edulis) Intake on Disease Activity in Female Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: the MIRA randomized cross-over dietary intervention. Nutrients. 2018;10(4):481.

Saboya PP, Bodanese LC, Zimmermann PR, Gustavo ADS, Macagnan FE, Feoli AP, et al. Lifestyle intervention on metabolic syndrome and its impact on quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2017;108:60–9.

Wang S-J, Wang Y-H, Huang L-C. Liquid combination of hyaluronan, glucosamine, and chondroitin as a dietary supplement for knee osteoarthritis patients with moderate knee pain: A randomized controlled study. Medicine. 2021;100(40):e27405.

Assaf AR, Beresford SAA, Risica PM, Aragaki A, Brunner RL, Bowen DJ, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern intervention and health-related quality of life: the women’s health initiative randomized controlled dietary modification trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(2):259–71.

Agarwal U, Mishra S, Xu J, Levin S, Gonzales J, Barnard ND. A Multicenter randomized controlled trial of a nutrition intervention program in a multiethnic adult population in the corporate setting reduces depression and anxiety and improves quality of life: the GEICO study. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(4):245–54.

Guo Y, Zhang M, Ye T, Qian K, Liang W, Zuo X, et al. Non-protein energy supplement for malnutrition treatment in patients with chronic kidney disease. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2022;31(3):504–11.

Kahleova H, Berrien-Lopez R, Holtz D, Green A, Sheinberg R, Gujral H, et al. Nutrition for hospital workers during a crisis: effect of a plant-based dietary intervention on Cardiometabolic outcomes and quality of life in healthcare employees during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2022;16(3):399–407.

Bourdel-Marchasson I, Ostan R, Regueme SC, Pinto A, Pryen F, Charrouf Z, et al. Quality of life: psychological symptoms—effects of a 2-month healthy diet and nutraceutical Intervention; a randomized, open-label intervention trial (RISTOMED). Nutrients. 2020;12(3):800.

Visvanathan R, Piantadosi C, Lange K, Naganathan V, Hunter P, Cameron ID, et al. The randomized control trial of the effects of testosterone and a nutritional supplement on hospital admissions in undernourished, community dwelling, older people. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(7):769–79.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Hamidianshirazi M, Shafiee M, Ekramzadeh M, Torabi Jahromi M, Nikaein F. Diet therapy along with Nutrition Education can Improve Renal Function in People with Stages 3–4 chronic kidney disease who do not have diabetes. (A randomized controlled trial). Br J Nutr. 2022:1–36.

Ho M, Ho JWC, Fong DYT, Lee CF, Macfarlane DJ, Cerin E, et al. Effects of dietary and physical activity interventions on generic and cancer-specific health-related quality of life, anxiety, and depression in colorectal cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(4):424–33.

Yeung SSY, Lee JSW, Kwok T. A Nutritionally complete oral nutritional supplement powder improved nutritional outcomes in free-living adults at risk of malnutrition: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11354.

Devlin N, Parkin D, Janssen B. Methods for Analysing and Reporting EQ-5D Data. Cham (CH): Springer Copyright 2020, The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s). This book is an open access publication.; 2020.

Abizanda P, López MD, García VP, Estrella JDD, da Silva González Á, Vilardell NB, et al. Effects of an oral nutritional supplementation plus physical exercise intervention on the physical function, nutritional status, and quality of life in frail institutionalized older adults: the ACTIVNES study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(5):439.e9-e16.

Andersson J, Hulander E, Rothenberg E, Iversen PO. Effect on body weight, quality of life and appetite following individualized, nutritional counselling to home-living elderly after rehabilitation – An open randomized trial. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(7):811–8.

Beck AM, Christensen AG, Hansen BS, Damsbo-Svendsen S, KreinfeldtSkovgaardMøller T. Multidisciplinary nutritional support for undernutrition in nursing home and home-care: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Nutrition. 2016;32(2):199–205.

Costan AR, Vulpoi C, Mocanu V. Vitamin D Fortified bread improves pain and physical function domains of quality of life in nursing home residents. J Med Food. 2014;17(5):625–31.

de Luis DA, Izaola O, López L, Blanco B, Colato CA, Kelly OJ, et al. AdNut study: effectiveness of a high calorie and protein oral nutritional supplement with β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate in an older malnourished population in usual clinical practice. Eur Geriatr Med. 2018;9(6):809–17.

Gomez G, Botero-Rodríguez F, Misas JD, Garcia-Cifuentes E, Sulo S, Brunton C, et al. A nutritionally focused program for community-living older adults resulted in improved health and well-being. Clin Nutr. 2022;41(7):1549–56.

Holst M, Søndergaard LN, Bendtsen MD, Andreasen J. Functional training and timed nutrition intervention in infectious medical patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(9):1039–45.

Matia Martin P, Robles Agudo F, Lopez Medina JA, Sanz Paris A, Tarazona Santabalbina F, Domenech Pascual JR, et al. Effectiveness of an oral diabetes-specific supplement on nutritional status, metabolic control, quality or life, and functional status in elderly patients. A multicentre study. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(3):1253–61.

Ming-Wei Z, Xin Y, Dian-Rong X, Yong Y, Guo-Xin L, Wei-Guo H, et al. Effect of oral nutritional supplementation on the post-discharge nutritional status and quality of life of gastrointestinal cancer patients after surgery: a multi-center study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2019;28(3):450–6.

Munk T, Svendsen JA, Knudsen AW, Østergaard TB, Thomsen T, Olesen SS, et al. A multimodal nutritional intervention after discharge improves quality of life and physical function in older patients & #x2013; a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(11):5500–10.

Parsons EL, Stratton RJ, Cawood AL, Smith TR, Elia M. Oral nutritional supplements in a randomised trial are more effective than dietary advice at improving quality of life in malnourished care home residents. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(1):134–42.

Söderström L, Bergkvist L, Rosenblad A. Oral nutritional supplement use is weakly associated with increased subjective health-related quality of life in malnourished older adults: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 2022;127(1):103–11.

van Beers M, Rutten-van Mölken MPMH, van de Bool C, Boland M, Kremers SPJ, Franssen FME, et al. Clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness of a 1-year nutritional intervention programme in COPD patients with low muscle mass: the randomized controlled NUTRAIN trial. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(2):405–13.

Wyers CE, Reijven PLM, Breedveld-Peters JJL, Denissen KFM, Schotanus MGM, van Dongen MCJM, et al. Efficacy of nutritional intervention in elderly after hip fracture: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2018;73(10):1429–37.

Blondal BS, Geirsdottir OG, Halldorsson TI, Beck AM, Jonsson PV, Ramel A. HOMEFOOD randomised trial & #x2013; Six-month nutrition therapy improves quality of life, self-rated health, cognitive function, and depression in older adults after hospital discharge. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2022;48:74–81.

Cramon MØ, Raben I, Beck AM, Andersen JR. Individual nutritional intervention for prevention of readmission among geriatric patients—a randomized controlled pilot trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2021;7(1):206.

Froghi F, Sanders G, Berrisford R, Wheatley T, Peyser P, Rahamim J, et al. A randomised trial of post-discharge enteral feeding following surgical resection of an upper gastrointestinal malignancy. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(6):1516–9.

Geaney F, Kelly C, Di Marrazzo JS, Harrington JM, Fitzgerald AP, Greiner BA, et al. The effect of complex workplace dietary interventions on employees’ dietary intakes, nutrition knowledge and health status: a cluster controlled trial. Prev Med. 2016;89:76–83.

Grönstedt H, Vikström S, Cederholm T, Franzén E, Luiking YC, Seiger Å, et al. Effect of sit-to-stand exercises combined with protein-rich oral supplementation in older persons: the older person’s exercise and nutrition study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(9):1229–37.

Huggins CE, Hanna L, Furness K, Silvers MA, Savva J, Frawley H, et al. Effect of early and intensive telephone or electronic nutrition counselling delivered to people with upper gastrointestinal cancer on quality of life: a three-arm Randomised controlled trial. Nutrients. 2022;14(15):3234.

Reinders I, Visser M, Jyväkorpi SK, Niskanen RT, Bosmans JE, Jornada Ben Â, et al. The cost effectiveness of personalized dietary advice to increase protein intake in older adults with lower habitual protein intake: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61(1):505–20.

Salamon KM, Lambert K. Oral nutritional supplementation in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis: a randomised, crossover pilot study. J Ren Care. 2018;44(2):73–81.

Sharma Y, Thompson CH, Kaambwa B, Shahi R, Hakendorf P, Miller M. Investigation of the benefits of early malnutrition screening with telehealth follow up in elderly acute medical admissions. QJM. 2017;110(10):639–47.

Smith TR, Cawood AL, Walters ER, Guildford N, Stratton RJ. Ready-made oral nutritional supplements improve nutritional outcomes and reduce health care use—a Randomised trial in older malnourished people in primary care. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):517.

Vivanti A, Isenring E, Baumann S, Powrie D, O’Neill M, Clark D, et al. Emergency department malnutrition screening and support model improves outcomes in a pilot randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(3):180–3.

Langabeer JR, Henry TD, Aldana CP, DeLuna L, Silva N, Champagne-Langabeer T. Effects of a community population health initiative on blood pressure control in Latinos. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(21):e010282.

Group TW. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–8.

Ayça S, Doğan G, Yalın Sapmaz Ş, Erbay Dündar P, Kasırga E, Polat M. Nutritional interventions improve quality of life of caregivers of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Nutr Neurosci. 2021;24(8):644–9.

Dimitrov Ulian M, Pinto AJ, de Morais Sato P, B. Benatti F, Lopes de Campos-Ferraz P, Coelho D, et al. Effects of a new intervention based on the Health at Every Size approach for the management of obesity: The “Health and Wellness in Obesity” study. PloS One. 2018;13(7):e0198401.

Lin S-C, Lin K-H, Tsai Y-C, Chiu E-C. Effects of a food preparation program on dietary well-being for stroke patients with dysphagia: a pilot study. Medicine. 2021;100(25):e26479.

Magalhães FG, Goulart RMM, Prearo LC. Impacto de um programa de intervenção nutricionalcom idosos portadores de doença renal crônica. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2018;23(8):2555–64.

Mościcka P, Cwajda-Białasik J, Jawień A, Szewczyk MT. Complex treatment of venous leg ulcers including the use of oral nutritional supplementation: results of 12-week prospective study. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology/Postępy Dermatologii i Alergologii. 2022;39(2):336–46.

Wu H, Wen Y, Guo S. Role of nutritional support under clinical nursing path on the efficacy, quality of life, and nutritional status of elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:9712330.

Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL™: Measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care. 1999;37(2):126–39.

Barnes C, Hall A, Nathan N, Sutherland R, McCarthy N, Pettet M, et al. Efficacy of a school-based physical activity and nutrition intervention on child weight status: Findings from a cluster randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2021;153:106822.

Poll FA, Miraglia F, D’avila HF, Reuter CP, Mello ED. Impact of intervention on nutritional status, consumption of processed foods, and quality of life of adolescents with excess weight. J Pediatr. 2020;96(5):621–9.

Richardson J, Sinha K, Iezzi A, Khan M. Modelling the utility of health states with the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) 8D instrument: overview and utility scoring algorithm. Research Paper 63, Center for Health Economics. 2011.

Richardson J, Chen G, Iezzi A, Khan MA. Transformations between the Assessment of Quality of Life AQoL instruments and test-retest reliability. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Health Economics, Monash University; 2011.

Richardson J, Elsworth G, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Mihalopoulos C, Schweitzer I, et al. Increasing the sensitivity of the AQoL inventory for the evaluation of interventions affecting mental health. Monash University Centre for Health Economics Research Paper. 2011;61.

Parletta N, Zarnowiecki D, Cho J, Wilson A, Bogomolova S, Villani A, et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: a randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci. 2019;22(7):474–87.

Whybird G, Nott Z, Savage E, Korman N, Suetani S, Hielscher E, et al. Promoting quality of life and recovery in adults with mental health issues using exercise and nutrition intervention. Int J Ment Health. 2022;51(4):424–47.

Richardson J, Atherton Day N, Peacock S, Iezzi A. Measurement of the quality of life for economic evaluation and the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) Mark 2 instrument. Aust Econ Rev. 2004;37(1):62–88.

Young AM, Mudge AM, Banks MD, Rogers L, Demedio K, Isenring E. Improving nutritional discharge planning and follow up in older medical inpatients: Hospital to Home Outreach for Malnourished Elders. Nutr Diet. 2018;75(3):283–90.

Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R. The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:209–24.

Han CY, Crotty M, Thomas S, Cameron ID, Whitehead C, Kurrle S, et al. Effect of individual nutrition therapy and exercise regime on gait speed, physical function, strength and balance, body composition, energy and protein, in injured, vulnerable elderly: a multisite randomized controlled trial (INTERACTIVE). Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3182.

Hunt SM, McEwen J, McKenna SP. Measuring health status: a new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1985;35(273):185–8.

Sanz-Paris A, Martinez-Trufero J, Lambea-Sorrosal J, Milà-Villarroel R, Calvo-Gracia F, Study obotD. Impact of an oral nutritional protocol with oligomeric enteral nutrition on the quality of life of patients with oncology treatment-related diarrhea. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):84.

Lin S, Hsiao YY, Wang M. The Profile of Mood States 2nd Edition. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2014;32(3):273–7.

Kobayashi Y, Kinoshita T, Matsumoto A, Yoshino K, Saito I, Xiao JZ. Bifidobacterium Breve A1 Supplementation Improved Cognitive Decline in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: An Open-Label, Single-Arm Study. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019;6(1):70–5.

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94.

Wills AM, Garry J, Hubbard J, Mezoian T, Breen CT, Ortiz-Miller C, et al. Nutritional counseling with or without mobile health technology: a randomized open-label standard-of-care-controlled trial in ALS. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):104.

Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19(8):787–805.

Chen HW, Ferrando A, White MG, Dennis RA, Xie J, Pauly M, et al. Home-based physical activity and diet intervention to improve physical function in advanced liver disease: a randomized pilot trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(11):3350–9.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The european organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–76.

Casas F, León C, Jovell E, Gómez J, Corvitto A, Blanco R, et al. Adapted ice cream as a nutritional supplement in cancer patients: impact on quality of life and nutritional status. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;14(1):66–72.

Cereda E, Cappello S, Colombo S, Klersy C, Imarisio I, Turri A, et al. Nutritional counseling with or without systematic use of oral nutritional supplements in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2018;126(1):81–8.

Chen L, Zhao M, Tan L, Zhang Y. Effects of five-step nutritional interventions conducted by a multidisciplinary care team on gastroenteric cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. Nutr Cancer. 2023;75(1):197–206.

de Souza APS, da Silva LC, Fayh APT. Nutritional intervention contributes to the improvement of symptoms related to quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):589.

Hassanin IA, Salih RFM, Fathy MHM, Hassanin EA, Selim DH. Implications of inappropriate prescription of oral nutritional supplements on the quality of life of cancer outpatients: a cross-sectional comparative study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(5):4149–55.

Huang S, Piao Y, Cao C, Chen J, Sheng W, Shu Z, et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial on the value of prophylactic oral nutritional supplementation in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients receiving chemo-radiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2020;111:105025.

Jian Z, Jian H, Qixun C, Jianguo F. Home enteral nutrition’s effects on nutritional status and quality of life after esophagectomy. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26(5):804–10.

Jiang W, Ding H, Li W, Ling Y, Hu C, Shen C. Benefits of oral nutritional supplements in patients with locally advanced nasopharyngeal cancer during concurrent Chemoradiotherapy: an exploratory prospective randomized trial. Nutr Cancer. 2018;70(8):1299–307.

Kim SH, Lee SM, Jeung HC, Lee IJ, Park JS, Song M, et al. The effect of nutrition intervention with oral nutritional supplements on pancreatic and bile duct cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Nutrients. 2019;11(5):1145.

Kong SH, Lee HJ, Na JR, Kim WG, Han D-S, Park S-H, et al. Effect of perioperative oral nutritional supplementation in malnourished patients who undergo gastrectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Surger. 2018;164(6):1263–70.

Meng Q, Tan S, Jiang Y, Han J, Xi Q, Zhuang Q, et al. Post-discharge oral nutritional supplements with dietary advice in patients at nutritional risk after surgery for gastric cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(1):40–6.

Miao J, Ji S, Wang S, Wang H. Effects of high quality nursing in patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy and related influence on self-care ability and pulmonary function. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(5):5476–83.

Najafi S, Haghighat S, Raji Lahiji M, RazmPoosh E, Chamari M, Abdollahi R, et al. Randomized study of the effect of dietary counseling during adjuvant chemotherapy on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting, and quality of life in patients with breast cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2019;71(4):575–84.

Nguyen LT, Dang AK, Duong PT, Phan HBT, Pham CTT, Nguyen ATL, et al. Nutrition intervention is beneficial to the quality of life of patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemotherapy in Vietnam. Cancer Med. 2021;10(5):1668–80.

Pinto E, Nardi MT, Marchi R, Cavallin F, Alfieri R, Saadeh L, et al. QOLEC2: a randomized controlled trial on nutritional and respiratory counseling after esophagectomy for cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(2):1025–33.

Poulsen GM, Pedersen LL, Østerlind K, Bæksgaard L, Andersen JR. Randomized trial of the effects of individual nutritional counseling in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(5):749–53.

Raji Lahiji M, Sajadian A, Haghighat S, Zarrati M, Dareini H, Raji Lahiji M, et al. Effectiveness of logotherapy and nutrition counseling on psychological status, quality of life, and dietary intake among breast cancer survivors with depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(10):7997–8009.

Regueme SC, Echeverria I, Monéger N, Durrieu J, Becerro-Hallard M, Duc S, et al. Protein intake, weight loss, dietary intervention, and worsening of quality of life in older patients during chemotherapy for cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(2):687–96.

Rupnik E, Skerget M, Sever M, Zupan IP, Ogrinec M, Ursic B, et al. Feasibility and safety of exercise training and nutritional support prior to haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with haematologic malignancies. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1142.

Sim E, Kim J-M, Lee S-M, Chung MJ, Song SY, Kim ES, et al. The effect of omega-3 enriched oral nutrition supplement on nutritional indices and quality of life in gastrointestinal cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23(2):485–94.

van der Werf A, Langius JAE, Beeker A, Ten Tije AJ, Vulink AJ, Haringhuizen A, et al. The effect of nutritional counseling on muscle mass and treatment outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(10):3005–13.

Werner K, de Küllenberg Gaudry D, Taylor LA, Keck T, Unger C, Hopt UT, et al. Dietary supplementation with n-3-fatty acids in patients with pancreatic cancer and cachexia: marine phospholipids versus fish oil - a randomized controlled double-blind trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16(1):104.

Xie H, Chen X, Xu L, Zhang R, Kang X, Wei X, et al. A randomized controlled trial of oral nutritional supplementation versus standard diet following McKeown minimally invasive esophagectomy in patients with esophageal malignancy: a pilot study. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(22):1674.

Yuce Sari S, Yazici G, Yuce D, Karabulut E, Cengiz M, Ozyigit G. The effect of glutamine and arginine-enriched nutritional support on quality of life in head and neck cancer patients treated with IMRT. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2016;16:30–5.

Zhu X, Liu D, Zong M, Wang J. Effect of swallowing training combined with nutritional intervention on the nutritional status and quality of life of laryngeal cancer patients with dysphagia after operation and radiotherapy. J Oral Rehabil. 2022;49(7):729–33.

Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Hammerlid E, Fayers P, Sezer O, Koller M, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(10):1384–94.

Sprangers MAG, Cull A, Groenvold M, Bjordal K, Blazeby J, Aaronson NK. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer approach to developing questionnaire modules: an update and overview. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(4):291–300.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–9.

Long Parma DA, Reynolds GL, Muñoz E, Ramirez AG. Effect of an anti-inflammatory dietary intervention on quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(7):5903–10.

Yanez B, Pearman T, Lis CG, Beaumont JL, Cella D. The FACT-G7: a rapid version of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) for monitoring symptoms and concerns in oncology practice and research. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):1073–8.

Miller MF, Li Z, Habedank M. A randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of coping with cancer in the kitchen, a nutrition education program for cancer survivors. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):3144.

Ribaudo JM, Cella D, Hahn EA, Lloyd SR, Tchekmedyian NS, Von Roenn J, et al. Re-validation and shortening of the Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy (FAACT) questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(10):1137–46.

Pascoe J, Jackson A, Gaskell C, Gaunt C, Thompson J, Billingham L, et al. Beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate/arginine/glutamine (HMB/Arg/Gln) supplementation to improve the management of cachexia in patients with advanced lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled phase II trial (NOURISH). BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):800.

Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):974–86.

Ward WL, Hahn EA, Mo F, Hernandez L, Tulsky DS, Cella D. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(3):181–95.

Wilson CB, Jones PW, O’Leary CJ, Cole PJ, Wilson R. Validation of the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in Bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(2):536–41.

Ahmadi A, Eftekhari MH, Mazloom Z, Masoompour M, Fararooei M, Eskandari MH, et al. Fortified whey beverage for improving muscle mass in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a single-blind, randomized clinical trial. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):216.

Dal Negro RW, Testa A, Aquilani R, Tognella S, Pasini E, Barbieri A, et al. Essential amino acid supplementation in patients with severe COPD: a step towards home rehabilitation. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2015;77(2):67–75.

Nguyen HT, Pavey TG, Collins PF, Nguyen NV, Pham TD, Gallegos D. Effectiveness of tailored dietary counseling in treating malnourished outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(5):778-91.e1.

Bilbao A, Escobar A, García-Perez L, Navarro G, Quirós R. The Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire: comparison of different factor structures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):23.

Guerra-Sánchez L, Fresno-Flores M, Martínez-Rincón C. Effect of a double nutritional intervention on the nutritional status, functional capacity, and quality of life of patients with chronic heart failure: 12-month results from a randomized clinical trial. Nutr Hosp. 2020;34(3):422–31.

Sánchez LG, Jurado MdMM, Cirujano ML, Castaño AV, Rincón CM, editors. Intervención nutricional en pacientes con insuficiencia cardíaca 3 meses después de los resultados de un ensayo clínico. 2019.

Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, McDermott A, Chassany O. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(5):540–51.

Kommers MJ, Silva Rodrigues RA, Miyajima F, Zavala Zavala AA, Ultramari V, Fett WCR, et al. Effects of probiotic use on quality of life and physical activity in constipated female university students: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(12):1163–71.

Micka A, Siepelmeyer A, Holz A, Theis S, Schön C. Effect of consumption of chicory inulin on bowel function in healthy subjects with constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2017;68(1):82–9.

Ettema TP, Dröes RM, de Lange J, Mellenbergh GJ, Ribbe MW. QUALIDEM: development and evaluation of a dementia specific quality of life instrument. Scalability, reliability and internal structure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(6):549–56.

Seemer J, Kiesswetter E, Fleckenstein-Sußmann D, Gloning M, Bader-Mittermaier S, Sieber CC, et al. Effects of an individualised nutritional intervention to tackle malnutrition in nursing homes: a pre-post study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13(3):741–52.

Stange I, Bartram M, Liao Y, Poeschl K, Kolpatzik S, Uter W, et al. Effects of a low-volume, nutrient- and energy-dense oral nutritional supplement on nutritional and functional status: a randomized, controlled trial in nursing home residents. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2013;14(8):628.e1-.e8.

Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwi M, Boparai N, King D. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45(2):295–300.

Alavinejad P, Hajiani E, Danyaee B, Morvaridi M. The effect of nutritional education and continuous monitoring on clinical symptoms, knowledge, and quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2019;12(1):17–24.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(2):102–11.

Hays RD, Kallich J, Mapes D, Coons S, Amin N, Carter WB, et al. Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SF ™), Version 1.3: A Manual for Use and Scoring. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 1997.

Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:64.

Strath LJ, Jones CD, Philip George A, Lukens SL, Morrison SA, Soleymani T, et al. The effect of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on pain in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Med. 2019;21(1):150–60.

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the mini asthma quality of life questionnaire. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(1):32–8.

Ma J, Strub P, Lv N, Xiao L, Camargo CA, Buist AS, et al. Pilot randomised trial of a healthy eating behavioural intervention in uncontrolled asthma. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(1):122–32.

Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Genovese BJ, Myers LW, Ellison GW. Comparison of a generic to disease-targeted health-related quality-of-life measures for multiple sclerosis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(5):557–69.

Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Harooni R, Myers LW, Ellison GW. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):187–206.

Mousavi-Shirazi-Fard Z, Mazloom Z, Izadi S, Fararouei M. The effects of modified anti-inflammatory diet on fatigue, quality of life, and inflammatory biomarkers in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Neurosci. 2021;131(7):657–65.

Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R. PDQ-39: a review of the development, validation and application of a Parkinson’s disease quality of life questionnaire and its associated measures. J Neurol. 1998;245(Suppl 1):S10–4.

Sheard JM, Ash S, Mellick GD, Silburn PA, Kerr GK. Improved nutritional status is related to improved quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2014;14(1):212.

Quittner AL, Marciel KK, Salathe MA, O’Donnell AE, Gotfried MH, Ilowite JS, et al. A preliminary quality of life questionnaire-bronchiectasis: a patient-reported outcome measure for bronchiectasis. Chest. 2014;146(2):437–48.

Doña E, Olveira C, Palenque FJ, Porras N, Dorado A, Martín-Valero R, et al. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Only Versus With Nutritional Supplementation in Patients With Bronchiectasis: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2018;38(6):411–8.

Lips P, Cooper C, Agnusdei D, Caulin F, Egger P, Johnell O, et al. Quality of life as outcome in the treatment of osteoporosis: The development of a questionnaire for quality of life by the European foundation for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7(1):36–8.

Bujang MA, Ismail M, Hatta N, Othman SH, Baharum N, Lazim SSM. Validation of the Malay version of Diabetes Quality of Life (DQOL) Questionnaire for Adult Population with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Malays J Med Sci. 2017;24(4):86–96.

Mohd Yusof B-N, Wan Zukiman WZHH, Abu Zaid Z, Omar N, Mukhtar F, Yahya NF, et al. Comparison of Structured Nutrition Therapy for Ramadan with Standard Care in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):813.

McHorney CA, Robbins J, Lomax K, Rosenbek JC, Chignell K, Kramer AE, et al. The SWAL–QOL and SWAL–CARE Outcomes Tool for Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults: III. Documentation of Reliability and Validity. Dysphagia. 2002;17(2):97–114.

Affairs UNDoEaS. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2020. World Economic Situation and Prospects (WESP). 2020:234.

Haraldstad K, Wahl A, Andenæs R, Andersen JR, Andersen MH, Beisland E, et al. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(10):2641–50.

Assari S, Lankarani MM, Montazeri A, Soroush MR, Mousavi B. Are generic and disease-specific health related quality of life correlated? The case of chronic lung disease due to sulfur mustard. J Res Med Sci. 2009;14(5):285–90.

Simpson KN, Hanson KA, Harding G, Haider S, Tawadrous M, Khachatryan A, et al. Patient reported outcome instruments used in clinical trials of HIV-infected adults on NNRTI-based therapy: a 10-year review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:164.

Wu AW, Hanson KA, Harding G, Haider S, Tawadrous M, Khachatryan A, et al. Responsiveness of the MOS-HIV and EQ-5D in HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapies. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:42.

Marín Caro MM, Laviano A, Pichard C. Impact of nutrition on quality of life during cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10(4):480–7.

Schünemann HJ, Sperati F, Barba M, Santesso N, Melegari C, Akl EA, et al. An instrument to assess quality of life in relation to nutrition: item generation, item reduction and initial validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:26.

Park S, Jung S, Yoon H. The role of nutritional status in the relationship between diabetes and health-related quality of life. Nutr Res Pract. 2022;16(4):505–16.

Bilgen F, Chen P, Poggi A, Wells J, Trumble E, Helmke S, et al. Insufficient calorie intake worsens post-discharge quality of life and increases readmission burden in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):756–64.

Bandayrel K, Wong S. Systematic literature review of randomized control trials assessing the effectiveness of nutrition interventions in community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43(4):251–62.

Bloom I, Zhang J, Parsons C, Bevilacqua G, Dennison EM, Cooper C, et al. Nutritional risk and its relationship with physical function in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(9):2031–9.

Sun B, Zhao Y, Lu W, Chen Y. The relationship of malnutrition with cognitive function in the older Chinese population: evidence from the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:766159.

Rasheed S, Woods RT. Malnutrition and quality of life in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):561–6.

Arensberg MB, Gahche J, Clapes R, Kerr KW, Merkel J, Dwyer JT. Research is still limited on nutrition and quality of life among older adults. Front Med. 2023;10:1225689.

Petrovsky DV, Ðoàn LN, Loizos M, O’Conor R, Prochaska M, Tsang M, et al. Key recommendations from the 2021 “inclusion of older adults in clinical research” workshop. J Clin Transl Sci. 2022;6(1):e55.

Singh H, Kanapuru B, Smith C, Fashoyin-Aje LA, Myers A, Kim G, et al. FDA analysis of enrollment of older adults in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 10-year experience by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):10009.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Cecilia Hofmann, PhD (C. Hofmann & Associates, Western Springs, IL) for her expert editorial assistance.

Funding

RCP and PGP performed work on this project as paid interns of Abbott.

KWK performed work on this project as part of employment with Abbott.

No other funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KWK conceptualized the project. RCP, PGP, and KWK compiled the data. RCP and KWK conducted the analysis and wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable. This manuscript is a literature review and didn’t require ethical approval by ethical committees or Internal Review Boards as it did not involve human subjects or animal studies.

Competing interests

KWK is an employee and stockholder of Abbott.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Figure 1.

Boolean logic of database searches. Supplemental Table 1. Compilation of included studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pemau, R.C., González-Palacios, P. & Kerr, K.W. How quality of life is measured in studies of nutritional intervention: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 22, 9 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-024-02229-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-024-02229-y