Abstract

Background

The regret intensity scale (RIS) and the regret coping scale for healthcare professionals (RCS-HCP) working in hospitals assess the experience of care-related regrets and how healthcare professional deal with these negative events. The aim of this study was to validate a German version of the RIS and the RCS-HCP.

Methods

The RIS and RCS-HCP in German were first translated into German (forward- and backward translations) and then pretested with 16 German-speaking healthcare professionals. Finally, two surveys (test and 1-month retest) administered the scales to a large sample of healthcare professionals from two different hospitals.

Results

Of the 2142 eligible healthcare professionals, 494 (23.1%) individuals (108 physicians) completed the cross-sectional web based survey and 244 completed the retest questionnaire. Participants (n = 165, 33.4% of the total sample) who reported not having experienced a regret in the last 5 years, had significantly more days of sick leave during the last 6 months. These participants were excluded from the subsequent analyses. The structure of the scales was similar to the French version with a single dimension for the regret intensity scale (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.88) and three types of coping strategies for the regret coping scale (alphas: 0.69 for problem-focused strategies, 0.67 for adaptive strategies and 0.86 for the maladaptive strategies). Construct validity was good and reproduced the findings of the French study, namely that higher regret intensity was associated with situations that entailed more consequences for the patients. Furthermore, higher regret intensity and more frequent use of maladaptive strategies were associated with more sleep difficulties and less work satisfaction.

Conclusions

The German RIS and RCS-HCP scales were found valid for measuring regret intensity and regret coping in a population of healthcare professionals working in a hospital. Reporting no regret, which corresponds to the coping strategy of suppression, seems to be a maladaptive strategy because it was associated with more frequent sick day leaves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Healthcare professionals are increasingly providing care to complex patients of older age, with multiple comorbidities [1] and from various cultural origins. How healthcare professionals respond to disparate groups of patients is a challenge, as well as how they deal with the contradictory needs of being empathic clinicians and dealing with the emotional burden of patients’ suffering, complications, or death [2]. Providing patient-centered and family-focused care implies more challenging medical and clinical decisions and the risk for unsatisfactory patient outcomes is greater, thereby generating strong negative emotions among healthcare professionals, such as ‘stress of consciences’ [3], moral distress [4], or feelings of loss of control [5].

Regret is a frequent emotional experience, which may be defined as a psychological state following an experience where one believes that the outcome would have been better if one had acted differently [6]. Regret develops in situations where healthcare professionals cannot fulfill what they believe to be the optimal care for their patients. In a cross-sectional survey of healthcare professionals in Switzerland, the prevalence of regret in a one-month period was 15% among nurses and 10% among physicians [7]. To cope with feelings of regret, people may use various strategies: the main distinction among coping strategies is problem-focused versus emotion-focused [8, 9]. Problem-focused coping strategies are directed towards reducing or eliminating a stressor or solving the situation, whereas emotion-focused coping strategies are directed towards changing one's own emotional reaction to the situation.

Regret in the healthcare setting occurs mainly when clinicians perceive their care as inappropriate [10] or futile [11], and in the context of defensive medicine [12]. Regrets also occur when clinicians are implicated in patient-adverse events or medical errors [13]. “Second victim” experiences are closely related to regret feelings [14, 15]. The consequences of these strong feelings manifest themselves at different levels. At the individual level, regret can lead to sleep problems [16–20], which can result in concentration deficits and higher risk of errors [21] or contribute to burnout [22]. At the patient-care level, regret can affect decision making [23], as well as learning and changing practice for future interventions [24–26], and again is associated with higher risk of error [16]. The decision-making process, especially in situations associated with a high workload, can trigger a variety of emotional reactions [27]. For example, anticipated regret is known to play a substantial role when physicians favor action (e.g., additional diagnostic tests) instead of inaction [24, 28]. At the institutional level, distress may increase turnover of staff members and days of sick leaves [29, 30].

Healthcare professionals’ emotional reactions have increasingly attracted scientific attention over the last decade [31–33]. However, there is a lack of valid instruments to measure regret intensity and regret regulation strategies in healthcare professionals [34], although regret can be conceptually quantified by the intensity of the emotion and coping can be assessed by the frequency of use of the various strategies [13, 35]. Such instruments should cover the main dimensions of emotion and emotion regulation, and should be reliable yet short, in order to allow monitoring regret at regular intervals. Two French speaking scales measuring regret intensity [36] and coping strategies [7] fulfill these requirements. Thus, the aim of this study is to translate and validate a German version of the Regret Intensity Scale (RIS) and the Regret Coping Scale of Health Care Professionals (RCS-HCP) [7, 36], developed in Switzerland.

Methods

Design

The steps to validate the RIS and RCS-HCP in German were first to contact two healthcare professionals in the German-speaking part of Switzerland (one physician, one psychotherapist) and to assess the conceptual validity of the scales in their cultural context. The scales were then translated, and pretested among German-speaking healthcare professionals. The final step was to use two surveys (test and retest) to administer the scales to a large sample of healthcare professionals from two different hospitals. The Ethics Committee of Zurich indicated that the research was exempted from formal research ethics approval because, as declared by Swiss law, it did not study a disease and did not use an intervention on health.

Scale translation

Two professional translators with expertise in the field of healthcare independently performed the translation of the two scales and the validation questions from French to German (forward translation). Then, two native French translators independently translated the German version back into French (backward translation). The backward translators were unaware of the original scales in French. A group of experts including three native German speakers and three native French speakers (two psychologists, three physicians and one medical sociologist) examined the translated items and selected the best translation for each item after the forward translation and after the backward translation.

Pretest

The first German versions of the Regret Intensity Scale (RIS) and Regret Regulation Scale (RCS-HCP) were pretested using one-on-one structured interviews by one interviewer at Stadtspital Triemli among 7 nurses, 8 doctors and 1 psychologist from a variety of clinics. The objective was to ensure that the translated items were clear and understandable for different professionals. During this process, 3 successive small adaptations and new versions of the questionnaire were made (see Additional file 1 for the final versions of these scales). There were no suggestions about additional domains that should be assessed.

Participants of the main survey

All professional email addresses of nurses and physicians of the Stadtspital Triemli, Zurich (500 bed hospital) and the Bezirksspital Affoltern am Albis (100 bed hospital) were collected. The participants, coming from all different departments and clinics, were informed by posters and flyers one week before the email was sent. Participants were informed that a small incentive for each completed questionnaire will be donated to the foundation Theodora (Giggle doctors for children: http://ch.theodora.org). The inclusion criteria were healthcare professionals currently working with patients; the exclusion criteria were professionals not having worked with patients for at least 5 years or retired.

Sample size calculation

To determine sample size, we used the rule of 10 respondents per 1 item [37] A subject to item ratio of 10 was an adequate compromise between goodness quality of factor analysis estimation (supposing large samples), the low and declining participation rates of healthcare professionals in surveys [23] and the small size of the two hospitals where the survey was conducted. Considering that the longest scale (RCS-HCP) has 15 items, 150 respondents were required. In order to be able to examine the psychometric properties of the scales separately among nurses and physicians, the minimum sample size was fixed at 300 (150 physicians, 150 other professionals).

Procedure

After the pretest of the translated questionnaire a cross-sectional survey with a web questionnaire was conducted. Up to three reminders were sent to the professional email addresses at a one-week interval. One month later the same questionnaire was sent to the participants who accepted to receive the retest.

Measurements

The questionnaire sent to all the participants contained, after an introduction and clear definition of the term regret, a single question about the most important regret, 6 questions about the consequences for the patient of the regretted situation (whether the regretted situation led to death, longer hospital stay, transfer to intensive care unit (ICU), extra surveillance, reanimation measures or durable physical or psychological handicap). There was also a single question about how much the respondent felt responsible for the situation (visual analogue scale from 0, Not at all, to 10, Very Responsible) and a question about whether the respondent felt this situation was an error (yes vs no). Regret intensity was measured by the German version of the regret intensity scale (RIS; 10 statements rated from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), which showed a good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87 in the French version). Regret coping strategies were measured by the German version of the regret coping scale for healthcare professionals [RCS-HCP; 15 statements rated from never or almost never (1) to always or almost always (4)]. This scale examines three types of coping strategies: problem-focused, maladaptive emotion-focused (self-attacking and rumination), and adaptive emotion-focused (all other strategies, considered as potentially helpful). All subscales measuring coping strategies showed good reliability in the French version, respectively 0.89, 0.89, and 0.89.

To assess construct validity, the insomnia severity index, the general job satisfaction scale and a general self-rated health question were added. The insomnia severity index (ISI) consists of 7 items rated from 0 to 4 (total score range: 0–28), with a higher score indicating more insomnia symptoms, with good alpha = 0.80. In a community sample, a threshold at 10 discriminated well between people with and without insomnia (as evaluated by a clinical interview) and the minimal important difference was 1.5 [38]. The general job satisfaction scale consists of 5 items on a 7-point scale [score ranging from Low (1) to High (7)] with a relatively low Cronbach’s alpha 0.61 [39]. The general self-rated health question corresponds to the first question from the SF-36 questionnaire, and has good criterion validity as it predicts mortality [40]. At the end of the survey, information on the socio-demographic and professional status of the participants were collected.

Statistical analyses

Participants who reported not having experienced a regret in the last 5 years were excluded from the analysis. Analyses related to the structure of the questionnaires were first run separately for physicians and nurses. Because the results were similar, analyses were then reported for the whole sample. For each item of the RIS and RCS-HCP, the percentage of the lowest and highest value was described. For each scale, we used principal component analysis to examine the number of underlying dimensions of the scale. If the scale had more than one component, we used exploratory factor analysis to obtain factor loadings and determine which items belong to which subscales. Analyses using item response theory for polytomous items (graded response model) supported the results of the factor analyses. The structure of the scales was also confirmed using confirmatory factor analysis, and reporting the recommended goodness-of-fit criteria and threshold: Chisquare/degrees of freedom (χ 2/df) should be <3, RMSEA should be <0.8, SRMR should be <0.10, and CFI should be >0.95 [41]. For each subscale, reliability was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha. Test-retest reliability was estimated using weighted kappa for items and intra-class correlation (ICC2) for total scores. In addition, for the RIS and the three coping strategies scores, their variability over time (i.e., measurement error) was examined by a Bland-Altman plot of the participants means at baseline and 1-month follow-up versus the differences in the scores [42]. The agreement interval of the differences provides the limits of agreement. At the end, construct validity was examined using correlations between continuous variables and t-tests when the construct validity variables were dichotomous. Analyses were done using R v3.3.1 (R foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Sample characteristics

Of 2196 participants who received an email invitation, 54 were excluded because they reported not working with patients for the last five years or being out of work, a further 148 refused to participate, and 1500 did not answer. Of the remaining 494 (23.1%) participants, 369 (74.7%) agreed to be contacted after one month, and 244 (66.1%) completed the questionnaire a second time.

The mean age of the participants was 39.1 years (SD = 10.2). The majority were women (81.8%), around one fourth of the respondents were physicians (21.9%). Professions other than medical doctors were grouped together for simplicity and because very few participants had a profession other than nurse or physician. Most employees worked at 80% or more. With respect to their health status, more than 25% of the healthcare professionals reported at least one sick leave day in the last 6 months, and 5% of the participants considered their health status as fair or poor. Healthcare professionals reported average levels of regret intensity (mean = 2.04, SD = 0.78, range =1-5) under the scale midpoints. For the coping strategies (range 1–4) they reported average levels of adaptive strategies (mean = 2.59, SD = 0.57) and problem-focused strategies (mean = 2.83, SD = 0.61) above the scale midpoints. Conversely, maladaptive strategies (mean = 1.78, SD = 0.63) were slightly under the scale midpoints.

Of the 494 participants, 165 (33.4%) reported not having experienced a regret in the last 5 years (Table 1). When compared with the participants reporting regrets, those reporting no regret were similar in terms of demographic characteristics (age, gender), as well as in job characteristics (clinical activity percentage, supervisor status and night-shift load). However, a significantly larger proportion of participants reporting no regret were non-physicians, and had between 6 and 10 years of experience. Furthermore, respondents reporting no regret indicated more often having had >3 days of sick leave during the last 6 months. This increased proportion of persons with a sick leave >3 days among healthcare professionals reporting no regret was similar for physicians and for non-physicians, though the smaller sample size did not allow for significant associations within professions. Indeed, among physicians, the proportion of sick leave was 1.1% when the reported at least one regret and 10.5% when they reported no regret (p = 0.06). Among non-physicians, these proportions were 6.0% versus 10.1%, respectively (p = 0.16).

Internal validity

Similarly to the French version, the principal component analysis of the regret intensity scale found a single component with all loadings above 0.40 (Table 2). The item with the lowest loading was “I feel anger rising in me” (“steigt Wut in mir auf.”). Confirmatory factor analysis showed a good fit of the model to the data: χ 2/df = 2.3, RMSEA = 0.07 (95% confidence interval: 0.06–0.08), SRMR = 0.07, CFI = 0.95. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88. The RIS, and the three RCS-HCP scores did not show any floor or ceiling effect.

With respect to the regret coping scale, the principal component analysis suggested 3 components based on Kaiser’s criterion and the screeplot. The loadings of the 3-factor structure reproduced the structure of the French version of the scales, with 5 items measuring problem-focused strategies, 5 items measuring emotion-focused strategies that are mostly maladaptive, and 5 items measuring adaptive emotion-focused strategies (Table 3). Confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable fit of the model to the data: χ 2/df = 2.1, RMSEA = 0.06 (95% confidence interval: 0.05–0.07), SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.96. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.69 for problem-focused, 0.86 for maladaptive, and 0.67 for adaptive strategies.

Construct validity

Table 4 presents the association of regret intensity with the consequences of the regret-inducing event. Perceived regret intensity was associated with the consequences for the patient and with patients’ unexpected death or death earlier than expected. Furthermore, regret intensity was higher when healthcare professionals felt more responsible for the situation. It was also associated with lower job satisfaction, more sleep problems and lower self-reported health.

With respect to regret coping strategies, problem-focused strategies were more frequent among supervisors (mean difference: 0.23, p = 0.002). Table 5 shows the association of regret coping strategies with healthcare professionals’ characteristics. There was a positive association between the intensity of the most regretted situation and the use of maladaptive strategies. Satisfaction with work was positively associated with the use of problem-focused and of adaptive strategies and negatively with the use of maladaptive strategies. Sleep problems were associated with more frequent use of maladaptive strategies, and, marginally, with less frequent use of problem-focused strategies. Finally, self-reported health was better among healthcare professionals who more frequently used adaptive strategies.

Test-retest reliability

For the test-retest results of the regret intensity scale, the participants who referred to a different regret-inducing event between the test and the retest were excluded. The intensity scale and the coping scale showed similar values across the two surveys with ICC ranging between 0.36 and 0.50 for the items of the RIS, and 0.36 and 0.63 for the items of the 3 coping subscales. The ICC of the overall scales were 0.52 for the RIS, and 0.68, 0.72, 0.60 for the problem-focused (PF), maladaptive (MA) and adaptive scales (A), respectively.

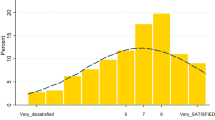

The Bland-Altman figures (Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4) for the baseline and the 1-month follow-up for regret intensity and the 3 regret coping strategies showed a good stability over time, with only a few healthcare professionals having a large change between baseline and follow-up, irrespective of the initial level.

Discussion

This study examined the reliability and validity of the German versions of the RIS and RCS-HCP. These instruments were found valid for measuring regret intensity and regret coping in a population of physicians and other healthcare professionals working in a hospital.

With respect to the reliability of the instruments, analogous factor structures were obtained with the French and the German versions of the scales. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s alpha of the RIS was good and almost identical to that of the French version (0.88 in this study compared to 0.89 in the French version). However, two dimensions of the regret coping scale had lower Cronbach’s alpha at 0.69 for problem-focused strategies and 0.67 for adaptive coping. This decrease could be due to differences in language and culture, but could also be due to differences in hospital type, because the two German-speaking hospitals included in this study were not teaching hospitals. Regarding linguistic and cultural differences, there were two important differences between the French and the German versions. One concerned the word ‘regret’. In the pretest interviews and in the comments on the survey, the term ‘Gefühl des Bereuens’ (i.e., our translation of regret) was criticized by the respondents as being a word they do not use very often. The German semantics has a more moralizing and judgmental connotation than the English or French word ‘regret’. The other difference concerned the question ‘I feel anger rising in me’, which had a substantially worse loading in the German translation. A hypothesis could be that the valence of anger in the German word ‘Wut’ is more intense or that in German-speaking regions the word ‘Wut’ is less acceptable [43] than the French word ‘colère’.

With respect to construct validity, results were again quite similar to those obtained with the French instruments, showing associations of regret intensity and regret coping with sleep problems, work satisfaction, and self-reported health. Thus, this study provides additional evidence indicating that the experience of intense regrets is associated with poor work satisfaction and more sleeping problems, which could be one reason for the high turnover in healthcare professions [22, 44]. However, the magnitudes of the associations were lower than those found with the French version of the scales, certainly in part due to the lower reliability of the German scales [45].

In addition to the validation of the scales, two results should be noted. First, as in the Geneva sample, about one third of the respondents did not report any regret. Yet, regret is a frequent emotion and is a common experience in healthy individuals [46]. Thus, reporting no regret seems unrealistic, and can be considered as a coping strategy. In this study, however, we found that this strategy (which can be seen as an extreme form of suppression, namely denial) was associated with more sick-day leaves, and, albeit non-significantly, with more sleep problems [17, 20]. This suggests that denial of regrets is a maladaptive strategy of coping with this experience, though it is possible that other factors, such as motivation towards their job, may also influence reporting no regret and health outcomes. A second interesting point was that with increasing regret intensity, people are more likely to use maladaptive coping strategies. This finding suggests that using ineffective coping strategies may happen when the situation experienced exceeds the healthcare professionals’ coping abilities. Thus, providing training in regret coping but also providing support for healthcare professionals who experienced intense distress is of paramount importance for healthcare professionals’ health, job performance, and quality of life.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it is a cross-sectional study, which only allows the estimation of associations but cannot show causality. Second, the response rate was low (23.1%), in line with many Internet surveys [47]. Reasons for the low response rate could be the fact that the participants were contacted via their professional email addresses briefly; some professionals were absent during the whole study time (vacation, maternity leave). Another hypothesis is that talking about regrets and emotions in general is a delicate topic for healthcare professionals. While the low response rate should not influence the validation of the scales, it questions the representativeness of the sample and may bias, for instance, the estimation of the prevalence of intense regret. In the same vein, the sample of our study mainly involved women and healthcare professionals other than physicians, and generalizability may thus be compromised. Thus, further studies should aim to obtain a representative sample using other methodologies. Finally, our study validated the instruments in a sample of healthcare professionals who admitted having experienced work-related regret. Since a third of the sample did not admit to feeling regret, a self-report measure cannot assess the intensity of their emotion following a potentially difficult situation. For these healthcare professionals, alternative measures able to detect processes either inaccessible to introspection or that the person might want to conceal may be necessary. Such measures include objective physiological manifestation of distress [48] or implicit measurement procedure [49] based on reaction time to assess automatic associations between regret and work.

Conclusions

The German version of the RIS and RCS- HCP are valid and reliable instruments to assess regret intensity and the use of coping strategies among healthcare professionals working in hospitals. Reporting no regret, which corresponds to the coping strategy of suppression, seems to be a maladaptive strategy because it was associated with more frequent sick day leaves. A practical implication of our study is that it may help evaluate important aspects of emotion regulation that frequently occur in healthcare professional settings. Further studies are needed to develop interventions specifically designed to help healthcare professionals to deal with emotionally challenging work experiences [50, 51].

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Adaptive

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- df:

-

Degree of freedom

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- ISI:

-

Insomnia severity index

- MA:

-

Maladaptive

- PF:

-

Problem-focused

- RCS-HCP:

-

Regret coping scale for healthcare professionals

- RIS:

-

Regret intensity scale

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean squared error of approximation

- SF-36:

-

The short form (36) health survey

- SRMR:

-

Standardized root mean residual

References

Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, Leland NE, Miller SC, Morden NE, Scupp T, Goodman DC, Mor V. Change in end-of-life care for medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2000;2013(309):470–7.

Newton BW. Walking a fine line: is it possible to remain an empathic physician and have a hardened heart? Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:233.

Glasberg AL, Eriksson S, Norberg A. Burnout and ‘stress of conscience’ among healthcare personnel. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:392–403.

St Ledger U, Begley A, Reid J, Prior L, McAuley D, Blackwood B. Moral distress in end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:1869–80.

Shapiro J, Astin J, Shapiro SL, Robitshek D, Shapiro DH. Coping with loss of control in the practice of medicine. Fam Syst Health. 2011;29:15–28.

Breugelmans SM, Zeelenberg M, Gilovich T, Huang W-H, Shani Y. Generality and cultural variation in the experience of regret. Emotion. 2014;14:1037–48.

Courvoisier DS, Cullati S, Ouchi R, Schmidt RE, Haller G, Chopard P, Agoritsas T, Perneger TV. Validation of a 15-item care-related regret coping scale for health-care professionals (RCS-HCP). J Occup Health. 2014;56:430–43.

Aldao A, Sheppes G, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation flexibility. Cognitive Ther Res. 2015;39:263–78.

Lazarus RS. Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:234–47.

Piers RD, Azoulay E, Ricou B, Dekeyser Ganz F, Decruyenaere J, Max A, Michalsen A, Maia PA, Owczuk R, Rubulotta F, et al. Perceptions of appropriateness of care among European and Israeli intensive care unit nurses and physicians. JAMA. 2011;306:2694–703.

Aghabarary M, Nayeri ND: Medical futility and its challenges: a review study. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2016;9:11.

Pellino IM, Pellino G. Consequences of defensive medicine, second victims, and clinical-judicial syndrome on surgeons’ medical practice and on health service. Updates Surg. 2015;67:331–7.

Courvoisier DS, Agoritsas T, Perneger TV, Schmidt RE, Cullati S. Regrets associated with providing healthcare: qualitative study of experiences of hospital-based physicians and nurses. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23138.

Edrees HH, Paine LA, Feroli ER, Wu AW. Health care workers as second victims of medical errors. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2011;121:101–8.

Ullstrom S, Andreen Sachs M, Hansson J, Ovretveit J, Brommels M. Suffering in silence: a qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:325–31.

Schmidt RE, Van der Linden M. The aftermath of rash action: Sleep-interfering counterfactual thoughts and emotions. Emotion. 2009;9:549–53.

Schmidt RE, Van der Linden M. Feeling too regretful to fall asleep: Experimental activation of regret delays sleep onset. Cog Therapy Res. 2013;37:872–80.

Schmidt RE, Renaud O, van der Linden M. Nocturnal regrets and insomnia in elderly people. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2011;73:371–93.

Schmidt RE, van der Linden M. The nocturnal return of neglected regrets: deficits in regret anticipation predict insomnia. Open Sleep J. 2011;4:20–5.

Schmidt RE, Cullati S, Mostofsky E, Haller G, Agoritsas T, Mittleman MA, Perneger TV, Courvoisier DS. Healthcare-related regret among nurses and physicians is associated with self-rated insomnia severity: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139770.

Seys D, Wu AW, Van Gerven E, Vleugels A, Euwema M, Panella M, Scott SD, Conway J, Sermeus W, Vanhaecht K. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2012;36:135–62.

Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:943–51.

Yl C, Johnson TP, Vangeest JB. Enhancing surveys of health care professionals: a meta-analysis of techniques to improve response. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36:382–407.

Sorum PC, Mullet E, Shim J, Bonnin-Scaon S, Chasseigne G, Cogneau J. Avoidance of anticipated regret: the ordering of prostate-specific antigen tests. Med Decis Making. 2004;24:149–59.

Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, DesRoches CM, Peugh J, Zapert K, Brennan TA. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293:2609–17.

Rohacek M, Buatsi J, Szucs-Farkas Z, Kleim B, Zimmermann H, Exadaktylos A, Stoupis C. Ordering CT pulmonary angiography to exclude pulmonary embolism: defense versus evidence in the emergency room. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1345–51.

Nendaz M, Perrier A. Diagnostic errors and flaws in clinical reasoning: mechanisms and prevention in practice. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13706.

Ziarnowski KL, Brewer NT, Weber B. Present choices, future outcomes: anticipated regret and HPV vaccination. Prev Med. 2009;48:411–4.

Giver H, Faber A, Hannerz H, Stroyer J, Rugulies R. Psychological well-being as a predictor of dropout among recently qualified Danish eldercare workers. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:239–45.

Heponiemi T, Kouvonen A, Vanska J, Halila H, Sinervo T, Kivimaki M, Elovainio M. The association of distress and sleeping problems with physicians’ intentions to change profession: the moderating effect of job control. J Occup Health Psychol. 2009;14:365–73.

Brosch T, Scherer KR, Grandjean D, Sander D. The impact of emotion on perception, attention, memory, and decision-making. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13786.

Kang EK, Lihm HS, Kong EH. Association of intern and resident burnout with self-reported medical errors. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34:36–42.

Courvoisier DS, Merglen A, Agoritsas T. Experiencing regrets in clinical practice. Lancet. 2013;382:1553–4.

Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Elwyn G. The importance and complexity of regret in the measurement of ‘good’ decisions: a systematic review and a content analysis of existing assessment instruments. Health Expect. 2011;14:59–83.

Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:281–91.

Courvoisier DS, Cullati S, Haller C, Haller G, Schmidt RE, Agoritsas T, Perneger TV. Validation of a 10-item care-related regret intensity scale (RIS-10) for healthcare professionals. Med Care. 2013;51:285–91.

Mueller RO. Structural equation modeling: back to basics. Struct Equ Modeling. 1997;4:353–69.

Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–8.

Blais MR, Brière NM, Riddle AS, Vallerand RJ. L’inventaire des motivations au travail de Blais. Revue québécoise de psychologie. 1993;14:185–215.

Bopp M, Braun J, Gutzwiller F, Faeh D, Group SNCS. Health risk or resource? Gradual and independent association between self-rated health and mortality persists over 30 years. PloS One. 2012;7:e30795.

Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. MPR-online. 2003;8:23–74.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10.

Cho J, Smith KC, Roter D, Guallar E, Noh DY, Ford DE. Needs of women with breast cancer as communicated to physicians on the internet. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:113–21.

Nei D, Snyder LA, Litwiller BJ. Promoting retention of nurses: a meta-analytic examination of causes of nurse turnover. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40:237–53.

Osborne JW. Effect sizes and the disattenuation of correlation and regression coefficients: lessons from educational psychology. Practical assessment, research and evaluation. 2003;8. http://ericae.net/pare/3~getvn.html.

Coricelli G, Dolan RJ, Sirigu A. Brain, emotion and decision making: the paradigmatic example of regret. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:258–65.

Irving MJ, Irving RJ, Sutherland S. Graseby MS16A and MS26 syringe drivers: reported effectiveness of an online learning programme. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2007;13(56):58–62.

Farquharson B, Bell C, Johnston D, Jones M, Schofield P, Allan J, Ricketts I, Morrison K, Johnston M. Nursing stress and patient care: real-time investigation of the effect of nursing tasks and demands on psychological stress, physiological stress, and job performance: study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:2327–35.

Fazio RH, Olson MA. Implicit measures in social cognition research: their meaning and use. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:297–327.

Dornan T, Pearson E, Carson P, Helmich E, Bundy C. Emotions and identity in the figured world of becoming a doctor. Med Educ. 2015;49:174–85.

Anwer LA, Abu-Zaid A. Transparency in medical error disclosure: the need for formal teaching in undergraduate medical education curriculum. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:23542.

Acknowledgements

All individuals who contributed towards the article are already included in the authors list.

Funding

Unrestricted grant from the University Hospitals of Geneva.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

DSC and SR conceived the research idea and design. All authors contributed for preparing and revising the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing of interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Zurich indicated that the research was exempted from formal research ethics approval.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0653-5.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

German version of the RIS and RCS-HCP scales. (DOCX 61 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Richner, S.C., Cullati, S., Cheval, B. et al. Validation of the German version of two scales (RIS, RCS-HCP) for measuring regret associated with providing healthcare. Health Qual Life Outcomes 15, 56 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0630-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0630-z