Abstract

Background

Understanding the association between methamphetamine (MA) use and HIV risk behavior among people who inject drugs (PWID) will assist policy-makers and program managers to sharpen the focus of HIV prevention interventions. This study examines the relationship between MA use and HIV risk behavior among men who inject drugs (MWID) in Tehran, Iran, using coarsened exact matching (CEM).

Methods

Data for these analyses were derived from a cross-sectional study conducted between June and July 2016. We assessed three outcomes of interest—all treated as binary variables, including distributive and receptive needle and syringe (NS) sharing and condomless sex during the month before interview. Our primary exposure of interest was whether study participants reported any MA use in the month prior to the interview. Firstly, we report the descriptive statistics for the pooled samples and matched sub-samples using CEM. The pooled and matched estimates of the associations and their 95% CI were estimated using a logistic regression model.

Results

Overall, 500 MWID aged between 18 and 63 years (mean = 28.44, SD = 7.22) were recruited. Imbalances in the measured demographic characteristics and risk behaviors between MA users and non-users were attenuated using matching. In the matched samples, the regression models showed participants who reported MA use were 1.82 times more likely to report condomless sex (OR = 1.82 95% CI 1.51, 4.10; P = 0.031), and 1.35 times more likely to report distributive NS sharing in the past 30 days, as compared to MA non-users (OR = 1.35 95% CI 1.15–1.81). Finally, there was a statistically significant relationship between MA use and receptive NS sharing in the past month. People who use MA in the last month had higher odds of receptive NS sharing when compared to MA non-users (OR = 4.2 95% CI 2.7, 7.5; P = 0.013).

Conclusions

Our results show a significant relationship between MA use and HIV risk behavior among MWID in Tehran, Iran. MA use was related with increased NS sharing, which is associated with higher risk for HIV exposure and transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There has been a growing trend of methamphetamine (MA) use in Iran over the last decade [1]. Bio-behavioral surveys conducted among PWID have shown increases in self-reported past month MA use from 42% in 2011 to 61% in 2013 [2]. Needle and syringe sharing and condomless sex place PWID at increased risk for HIV and other infections [3,4,5,6] with international studies showing this risk is increased further when MA is the primary drug used [7, 8]. There is also evidence to show PWID who use MA are more likely to share needles when injecting, and to not consistently use sterile injection equipment when compared to PWID who do not report MA use [9]. Furthermore, MA is a stimulant that enhances sex drive, lowers inhibitions and increases self-confidence. Some people who use opioids or receive opioid maintenance treatment (OMTs) report MA use as a way to increase sex drive and performance [10]. As a result, people who use MA may be more likely to engage in HIV risk behaviors, such as having condomless sex and exchanging sex for money [11]. There is evidence showing MA injecting can negatively impact the effectiveness of harm reduction programs including needle and syringe programs (NSPs), and opiate maintenance therapy (OMT) [12].

Previous international studies have assessed the relationship between MA use, unsafe sexual and injection risk behaviors among PWID using observational methods [7]; however, observational studies have methodological limitations (i.e., confounders) [13]. Logistical and ethical issues mean that experimental studies using MA are difficult to conduct therefore the use of novel approaches exploring the impact of MA use on risk taking behaviors are required. Little is also known about the effect of MA use on injection and sexual behavior among PWID in developing countries, especially Iran [14]. To address these limitations in the literature, we performed Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) to analyze data collected from interviews with PWID.

In the present study, we applied CEM to construct statistically equivalent groups of survey respondents who were susceptible and not susceptible to MA use. Understanding this association will assist policy-makers and program managers to sharpen the focus of their HIV prevention interventions. Therefore, the main of this study was to measure the effect of MA use on the injecting risk behaviors of MWID in Tehran, Iran.

Methods

Study sample and procedures

Data for these analyses were collected using a cross-sectional survey with MWID conducted between June and July 2016 in Tehran, Iran. The study design and setting have been described in detail elsewhere [15] with PWID being recruited using convenience and snowball sampling from drop-in centers located in southern Tehran. PWID were eligible for inclusion in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) were aged over 18 years, (2) reported injecting drugs at least once in the month before interview, and (3) could provide informed consent to participate in the study. Participants completed a modified version of the behavioral surveillance surveys (BSS) used previously in Iran [16].

The questionnaire included modules on socio-demographic characteristics (age, marital status, education level, and living status), drug use history, injecting risk behaviors including receptive syringe sharing (obtaining and using a syringe after being used by someone else), and distributive syringe sharing (giving someone else a syringe after it has already been used) and high risk sexual behaviors (condomless anal and/or vaginal intercourse). Data collection and written informed consent was obtained by trained research staff.

We assessed three outcomes of interest, all treated as binary variables, including distributive and receptive needle sharing and condomless sex with any type of sexual partner in the month before interview. The receptive sharing variable was derived from a survey question which asked participants: “in the last 30 days, with how many people did you use a needle after they injected with it?” The responses were dichotomized into any receptive sharing in the last month (yes vs. no). The condomless sex variable was derived from survey questions which asked participants about engaging in sex with a partner without using a condom in the last month (including regular, casual or commercial sex partners). Our primary exposure of interest was whether study participants had reported MA use in the month prior to the interview. Based on exposure status, we created two groups: exposure (i.e., MA use) and control (i.e., no reported MA-use) groups. Verbal and written consent procedures were provided to all participants before the survey was administered.

Analysis methods

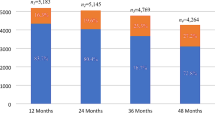

Firstly, we report the descriptive statistics for the pooled sample and matched sub-samples using CEM. CEM is a nonparametric method of preprocessing data to control for some or all of the potentially confounding influences of pretreatment control variables by reducing imbalance between the treated and control groups. We used CEM to match the groups based on certain covariates and thus made statistically equivalent comparison groups to estimate the independent effect of MA use on both injection and sexual risk-taking behaviors. The CEM created comparable subgroups based on covariates including housing status, income, current OMT, education level, and whether participants access NSP. These behaviors were assessed because they were found to be associated with injection risk-taking and risky sexual behaviors [17,18,19], and therefore, may be confounders of the association between MA use and specific HIV risk behaviors. Using CEM, we allocated every study participant into one of a specified set of stratum in which all were exactly matched on a set of coarsened variables. Matched members were then assigned a weight specific to that stratum and representative of the proportion of all members present in that stratum. Then, we calculated a statistical measure called L1 distance. We calculated the overall imbalance using the L1 statistic before and after matching (indicating minimal imbalance between the two comparison groups). Then, the pooled and matched estimates of the association and their 95% CI were estimated using a logistic regression model. All data analysis was performed using Stata V.12

Results

The sample included 500 male PWID, aged between 18 and 63 years (mean = 28.44, SD = 7.22). The majority of participants (73%) were currently single, had not completed high school (72%), and 64% reported their initiation into injecting drug use before 25 years of age. Additionally, 27.3% were homeless, and 67.3% had monthly incomes of less than $150. Over three quarters (78%) of participants reported receiving OMTs for at least 2 months and 70% reported accessing a needle syringe program (NSP) in the past 6 months.

As seen in the matched sample “receptive” and “distributive” syringe sharing in the month before interview was reported by 44% and 24%, of PWID respectively. In addition, 73% of participants reported “inconsistent condom use with any sex partner” in the previous 30 days. Also, 70% of participants reported MA use in the month before interview. The results of the subgroup analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 2 presents estimates of the effect of MA use on both injecting and sexual risk taking in the matched and unmatched samples. In the matched samples, the regression models showed participants who reported MA use were 1.82 times more likely to have condomless sex (OR = 1.82 95% CI 1.51, 4.10; P = 0.031) and 1.35 times more likely to report distributive needle sharing in the past 30 days, when compared to MA non-users (OR = 1.35 95% CI 1.15–1.81; P = 0.012). Finally, there was a statistically significant relationship between MA use and reported receptive syringe sharing in past month. People who used MA last month had higher odds of receptive syringe sharing when compared to those not reporting any MA use (OR = 1.36 95% CI 1.11, 1.85; P = 0.013).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that in this group of PWID, MA use increases the risk of past month condomless sex and receptive and distributive syringe sharing. Collectively, these findings are consistent with previous studies that have identified significant associations between condomless sex and MA use [20, 21]. PWID reporting recent MA use were more likely to have condomless sex than MA non-users. An Australian study found that most people (72%), who use MA frequently, reported being sexually active but only 35% of them reported regular condom use with their casual partners in the last month [22]. A study of men referred to one of three HIV prevention and testing program in California (N = 1839) found high rates (11.1%) of amphetamines and sildenafil citrate (Viagra®) use [23]. HIV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases were higher among those who used both amphetamines and Viagra® compared to those who used only one or neither drug. Viagra® use was associated with insertive anal intercourse, and methamphetamine was associated with receptive anal intercourse [23]. An earlier study conducted among men who have sex with men in the same city found taking Viagra® at the same time as MA was associated with insertive anal intercourse [24].

Our findings show that MA increases receptive syringe sharing in the past month. This finding is consistent with other studies [3, 25]. Our study revealed an independent relationship between syringe sharing and MA use and suggests that PWID are at increased risk for exposure to HIV and other blood-borne infections. Our results regarding drug-related HIV-risk behaviors suggest that risk practices related to injecting may reflect another important aspect of HIV transmission among people who use MA.

The production of crystal MA in clandestine laboratories is highly profitable and easy to hide, with evidence suggesting that law enforcement interventions have had a limited effect on the production or importation to main international markets in North America and Europe [26]. Since 1996, precursor chemicals for MA production have been scheduled and highly regulated in the US resulting in temporary perceived disturbances in MA markets, with little effect on MA use and related health problems among MA users [27, 28]. Thus, it is essential to implement evidence-based HIV prevention, drug treatment, and harm reduction interventions to address MA use among PWID and reduce high risk behaviors in this population [29, 30]. Our study shows that there is an independent relationship between syringe sharing and MA injection and suggests that individuals who inject MA are more susceptible to HIV and other blood-borne infections infection.

Consistent with previous studies [3, 31], we found that participants who used MA were more likely than MA non-users to report distributive needle sharing in the month before interview.

The results of our study provide several insights for future studies investigating injection-related risk behavior especially among younger (under 25 years) MA injectors. Considering that MA users are more likely to experience barriers to accessing harm reduction and HIV prevention services, interventions and approaches that improve secondary syringe distribution (i.e., receiving supplies from peers who access NSPs) are essential [32]. Studies indicate that models of syringe distribution, including fixed and outreach-based services performed by or catered specifically to youth, are advantageous in other settings [33]. The development of youth-friendly supervised injecting facilities acceptable to those injecting MA are also worthy of further investigation as they decrease syringe sharing among hard-to-reach and hidden populations [34].

In addition, interventions that improve positive peer norms about harm reduction efforts among MA-using injecting networks may be efficient at decreasing risk-taking behavior and supporting the use of HIV prevention and other health services [35]. Creating effective HIV prevention approaches by working with MA injectors must consider the injecting practices and health problems experienced by these individuals [36].

Our results show that those who injected MA report inadequate access to sterile syringes. Further research investigating the most prevalent individual, social, and structural obstacles experienced by those who inject MA is required. However, the present study indicates that NSP offered by adult injectors can positively influence HIV prevention interventions for this population [37, 38].

There is some suggestion that MA injectors do not feel comfortable when using the HIV prevention interventions that are provided for users of other drugs [12]. Therefore, MA injectors themselves must be prioritized in the development of new interventions, including placing services in areas frequented by young people who use MA and adopting peer-based staffing models for future NSP expansion.

Although there are structural barriers which are associated to the ability of individuals to access HIV prevention services, other individual factors and social influences exist that prevent MA injectors from accessing sterile syringes [39]. Previous studies have shown that MA injectors are more susceptible to inject within friendship groups, and this may increase the risk of sharing of syringes and other injecting equipment [40]. It is recommended that future studies investigate the barriers to service utilization and to determine how individual, social, and structural barriers increase HIV-related harms.

Our study had several limitations including the cross-sectional design and the use of self-report data. Since our data are not a random sample from the population under investigation, generalizing the results to other drug-users or other settings is limited.

Previous studies have indicated that PWID self-reports are valid [41, 42], but, since syringe sharing behavior is stigmatized, it may be underreported [43].

HIV prevention, harm reduction, and education programs are required to reduce HIV risk taking by people who use MA. Given there are currently few evidenced informed interventions for MA use among PWIDs in Iran our results provide essential information for expanding risk reduction programs and interventions.

Conclusion

Our results show a significant relationship between MA use and HIV risk behavior among PWID in Tehran, Iran. MA use was related with an increased risk of syringe sharing, which is associated with greater risk for HIV infection transmission. Current law enforcement measures have failed to control the MA market and therefore the development of specific drug treatment and harm reduction interventions addressing specific needs of PWID who use MA are urgently needed. It is recommended that novel, PWID-driven interventions, including the development of current services to resolve the requirements of this population be developed to decrease HIV transmission among people who inject methamphetamine.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BSS:

-

Behavioral surveillance surveys

- CEM:

-

Coarsened exact matching

- DICs:

-

Drop-in centers

- MA:

-

Methamphetamine

- MWID:

-

Men who inject drugs

- NSPs:

-

Needle and syringe programs

- OMT:

-

Opioid maintenance treatment

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- PWID:

-

People who inject drugs

References

Shadloo B, Amin-Esmaeili M, Haft-Baradaran M, Noroozi A, Ghorban-Jahromi R, Rahimi-Movaghar A. Use of amphetamine-type stimulants in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2004-2015: a review. East Mediterr Health J. 2017;23(3).

Radfar SR, Mohsenifar S, Noroozi A. Integration of methamphetamine harm reduction into opioid harm reduction services in Iran: preliminary results of a pilot study. Iranian J Psychiatr Behav Sci. 2017;11(2).

Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Buxton JA, Li K, Montaner JS, Wood E. Increasing use and associated harms of crystal methamphetamine injection in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(2-3):313–6.

Noroozi M, Ahounbar E, Karimi SE, Ahmadi S, Najafi M, Bazrafshan A, Shushtari ZJ, Farhadi MH, Higgs P, Rezaei F, et al. HIV Risk Perception and Risky Behavior Among People Who Inject Drugs in Kermanshah, Western Iran. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24(4):613–8.

Noroozi M, Noroozi A, Sharifi H, Harouni GG, Marshall BDL, Ghisvand H, Qorbani M, Armoon B. Needle and Syringe Programs and HIV-Related Risk Behaviors Among Men Who Inject Drugs: A Multilevel Analysis of Two Cities in Iran. Int J Behav Med. 2019;26(1):50–8.

Armoon B, Noroozi M, Jorjoran Shushtari Z, Sharhani A, Ahounbar E, Karimi S, Ahmadi S, Farhoudian A, Rahmani A, Abbasi M, et al. Factors associated with HIV risk perception among people who inject drugs: Findings from a cross-sectional behavioral survey in Kermanshah, Iran. J Subst Abus. 2018;23(1):63–6.

Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Wechsberg WM, Schlenger WE. Injection drug use among stimulant users in a national sample. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(1):61–83.

Molitor F, Ruiz JD, Flynn N, Mikanda JN, Sun RK, Anderson R. Methamphetamine use and sexual and injection risk behaviors among out-of-treatment injection drug users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(3):475–93.

Molitor F, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. West J Med. 1998;168(2):93.

Noroozi A, Malekinejad M, Rahimi-Movaghar A. Factors influencing transition to Shisheh (Methamphetamine) among young people who use drugs in Tehran: A qualitative study. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2018;50(3):214–23.

Control CfD, Prevention. Increasing morbidity and mortality associated with abuse of methamphetamine--United States, 1991-1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(47):882.

Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Guarinieri M, Panda S, Phillips B, Strathdee SA, Tyndall M, Wiessing L, Wodak A, Howard J. Meth/amphetamine use and associated HIV: Implications for global policy and public health. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(5):347–58.

Noroozi M, Marshall BD, Noroozi A, Armoon B, Sharifi H, Farhoudian A, Ghiasvand H, Vameghi M, Rezaei O, Sayadnasiri M. Do needle and syringe programs reduce risky behaviours among people who inject drugs in Kermanshah City, Iran? A coarsened exact matching approach. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37:S303–8.

Noroozi M, Marshall BD, Noroozi A, Armoon B, Sharifi H, Qorbani M, Abbasi M, Bazrafshan MR. Effect of alcohol use on injection and sexual behavior among people who inject drugs in Tehran, Iran: A coarsened exact matching approach. J Res Health Sci. 2018;18(2).

Bazrafshan MR, Noroozi M, Ghisvand H, Noroozi A, Alibeigi N, Abbasi M, Higgs P, Armoon B. Comparing Injecting Risk Behaviors of Long-Term Injectors with New Injectors in Tehran, Iran. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(2):185–90.

HIV Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey (BBSS) among People Who Inject Drugs, I. R. Iran in 2014: Project Report [In Persian]. HIV/STI Surveillance Research Center, and WHO Collaborating Center for HIv Surveillance, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

Noroozi M, Ahmadi S, Armoon B, Jorjoran Shushtari Z, Sharhani A, Ahounbar E, Karimi SE, Rahmani A, Mokhayeri Y, Qorbani M. Social determinants associated with risky sexual behaviors among men who inject drugs in Kermanshah, Western Iran. J Subst Abus. 2018;23(6):591–6.

Ghiasvand H, Bayani A, Noroozi A, Marshall BD, Koohestani HR, Hemmat M, Mirzaee MS, Bayat AH, Noroozi M, Ahounbar E, et al. Comparing injecting and sexual risk behaviors of long-term injectors with new injectors: A meta-analysis. J Addict Dis. 2018;37(3-4):233–44.

Rezaei O, Ghiasvand H, Higgs P, Noroozi A, Noroozi M, Rezaei F, Armoon B, Bayani A. Factors associated with injecting-related risk behaviors among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. J Addict Dis. 2020:1–18.

McNall M, Remafedi G. Relationship of amphetamine and other substance use to unprotected intercourse among young men who have sex with men. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(11):1130–5.

Maher L, Phlong P, Mooney-Somers J, Keo S, Stein E, Couture M, Page K. Amphetamine-type stimulant use and HIV/STI risk behaviour among young female sex workers in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22(3):203–9.

Baker A, Lee NK, Claire M, Lewin TJ, Grant T, Pohlman S, Saunders JB, Kay-Lambkin F, Constable P, Jenner L. Drug use patterns and mental health of regular amphetamine users during a reported ‘heroin drought’. Addiction. 2004;99(7):875–84.

Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Ware MR, Napper LE. Methamphetamine and Viagra use: relationship to sexual risk behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(2):273–9.

Spindler HH, Scheer S, Chen SY, Klausner JD, Katz MH, Valleroy LA, Schwarcz SK. Viagra, methamphetamine, and HIV risk: results from a probability sample of MSM, San Francisco. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(8):586–91.

Burt RD, Thiede H. Evidence for risk reduction among amphetamine-injecting men who have sex with men; Results from National HIV Behavioral Surveillance surveys in the Seattle area 2008–2012. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(10):1998–2008.

Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, Li K, Kerr T, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, O'shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Unsafe injection practices in a cohort of injection drug users in Vancouver: Could safer injecting rooms help? Cmaj. 2001;165(4):405–10.

Cunningham JK, Liu LM. Impacts of federal precursor chemical regulations on methamphetamine arrests. Addiction. 2005;100(4):479–88.

Cunningham JK, Liu LM. Impacts of federal ephedrine and pseudoephedrine regulations on methamphetamine-related hospital admissions. Addiction. 2003;98(9):1229–37.

Reuter P, Caulkins JP. Does precursor regulation make a difference? Addiction. 2003;98(9):1177–9.

Kerr T, Wood E, Grafstein E, Ishida T, Shannon K, Lai C, Montaner J, Tyndall M. High rates of primary care and emergency department use among injection drug users in Vancouver. J Public Health. 2004;27(1):62–6.

Al-Tayyib A, Koester S, Langegger S, Raville L. Heroin and methamphetamine injection: An emerging drug use pattern. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(8):1051–8.

Ball AL. HIV, injecting drug use and harm reduction: a public health response. Addiction. 2007;102(5):684–90.

Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Lum PJ, Ochoa K, Moss AR. Hepatitis C virus infection and needle exchange use among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Hepatology. 2001;34(1):180–7.

Boyd J, Fast D, Hobbins M, McNeil R, Small W. Social-structural factors influencing periods of injection cessation among marginalized youth who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada: an ethno-epidemiological study. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14(1):31.

Kerr T, Tyndall M, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. Safer injection facility use and syringe sharing in injection drug users. Lancet. 2005;366(9482):316–8.

Degenhardt L, Baker A, Maher L. Methamphetamine: geographic areas and populations at risk, and emerging evidence for effective interventions; 2008.

Bailey SL, Huo D, Garfein RS, Ouellet LJ. The use of needle exchange by young injection drug users. JAIDS J Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;34(1):67–70.

Gindi RM, Rucker MG, Serio-Chapman CE, Sherman SG. Utilization patterns and correlates of retention among clients of the needle exchange program in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103(3):93–8.

Darke S, Ross J, Cohen J, Hando J, Hall W. Injecting and sexual risk-taking behaviour among regular amphetamine users. AIDS Care. 1995;7(1):19–26.

Kaye S, Darke S. A comparison of the harms associated with the injection of heroin and amphetamines. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58(1-2):189–95.

Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51(3):253–63.

Lapworth K, Dawe S, Davis P, Kavanagh D, Young R, Saunders J. Impulsivity and positive psychotic symptoms influence hostility in methamphetamine users. Addict Behav. 2009;34(4):380–5.

Des Jarlais DC, Paone D, Milliken J, Turner CF, Miller H, Gribble J, Shi Q, Hagan H, Friedman SR. Audio-computer interviewing to measure risk behaviour for HIV among injecting drug users: a quasi-randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1657–61.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Haedar Mohammadi to the work reviewing the evidence.

Funding

This Project was funded by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWRS), Tehran, Iran

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN and BA conceived of and facilitated the development of the project and led the data collection, analysis, and writing of the results. AN, AB, LFM, and BM participated in the conceptualization, data collection, refinement, and analysis of the results of the study. RA, ANA, and MRB participated in the data collection, refinement, and primary analysis of the results of the study. All authors contributed to the discussion and reflections regarding participation in the project and the lessons drawn from the project. BA, MN, PH, and AN drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the project was provided by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval No.: USWR.1396.54). All participants in this study provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Noroozi, M., Higgs, P., Noroozi, A. et al. Methamphetamine use and HIV risk behavior among men who inject drugs: causal inference using coarsened exact matching. Harm Reduct J 17, 66 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00411-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00411-1