Abstract

Background

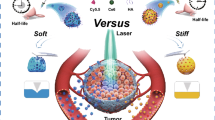

Stimulus-responsive degradable mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles (MONs) have shown great promise as drug carriers via enhancing the efficiency of drug delivery and accelerating the degradation of nanocarriers. However, it remains a great challenge to develop novel light-enabled spatial and temporal degradable MONs with both superior responsiveness for efficient anti-cancer drug delivery and safe exocytosis.

Results

We report a novel photo-responsive degradable hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoplatform (HMONs@GOQD). The platform is based on organosilica nanoparticles (HMONs) containing singlet oxygen (1O2)-responsive bridged organoalkoxysilanes and wrapped graphene oxide quantum dots (GOQDs). The unique hollow mesoporous structure of the HMONs guarantees an excellent drug loading and release profile. During light irradiation, 1O2 produced by the GOQDs leads to the degradation of the organosilica nanoparticles, resulting in enhanced local drug release.

Conclusions

We carried out in vitro and in vivo experiments using DOX as a model drug; DOX-HMONs@GOQDs exhibited high biocompatibility, accelerated degradation, and superior therapeutic efficacy during light irradiation, indicating a promising platform for clinical cancer therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With the development of nanotechnology, smart drug delivery systems (DDS) have been widely employed to overcome the side effects of anti-cancer drugs in chemotherapy [1,2,3,4]. Numerous small-scale DDS (nanoparticles and microparticles) are fabricated using various biocompatible materials, such as organic molecules, lipids, polymers, and inorganic nanomaterials. They enables the targeted delivery of drugs to tumors owing to the engineered surfaces of the DDS and the effect of their enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) of tumor cells [5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, as well as unique chemical stability, a high surface area, tunable size, and porosity, ideal DDS have biorelated degradability and clearance as essential features. Some DDS comprising particles with sizes larger than 10 nm can be taken up by the liver and spleen, which gives rise to long-term toxicity concerns [11,12,13,14,15].

Although some DDS derived from polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) with special organic chemical structures, such as poly(lactic acid) [16,17,18,19], poly(lactide-co-glycolide) [20,21,22,23,24], and poly(ε-caprolactone) [25,26,27,28], are degradable in biological environments, inefficient drug loading and mechanical and chemical instability still impede their clinical translation. Therefore, nanoparticles with the advantages of both organic (biodegradability) and inorganic (unique chemical stability, high surface area, tunable size, and porosity) nanomaterials would pave the way to the preparation of ideal drug delivery systems [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

Mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles (MONs)based on bridged organoalkoxysilanes with two or more alkoxysilyls have been designed due to the advantages of the siloxane matrix, such as a defined porous framework and specific organic functionalities [37,38,39,40,41,42]. The unique high surface area and mesoporous structure of MONs contribute to their drug loading efficiency. To accelerate the degradation of MONs, and address the long-term toxicity concerns, stimuli-responsive bridged organoalkoxysilanes have also been introduced to prepare biodegradable MONs. For instance, disulfide bridges have been incorporated into the walls of MONs to create redox-responsive biodegradable nanoparticles, which rely on the cleavage of sulfide bridges by intracellular bioreducing agents such as glutathione tripeptides [43,44,45,46,47,48]. Oxamide–phenylene bridges, which are biodegradable in the presence of trypsin proteins, have also been reported [49]. Such biodegradable MONs-based DDS are safe with regard to exocytosis, overcome the long-term toxicity concerns, and release the loaded drug more readily.

Compared with the stimulus provided by the specific chemical properties of the cellular environment, an external light source enables better spatiotemporal dosing of the loaded drug, and more responsive on-demand degradation of the DDS. Some effective DDS using MONs as drug containers have been developed for photo-responsive drug delivery, however, the degradation of the MONs themselves relies on the cellular environment, which is a relatively slow process [50, 51]. Therefore, the design and fabrication of novel photo-induced biodegradable MONs would not only speed up the release of the loaded drugs, but would also accelerate the safe exocytosis of the DDS. This would be significant for the future clinical transformation of MONs-based DDS.

In the present study, we designed and fabricated a novel photo-responsive hollow degradable mesoporous organosilica nanoplatform for anti-cancer drug delivery. The nanoplatform was based on singlet oxygen (1O2)-responsive bridged organoalkoxysilanes (from a 9,10-dialkoxy-anthracene (DN)-based precursor), and wrapped graphene quantum dots (GOQDs). The hollow structures of the organosilica nanoparticles (HMONs) used for the platform were intended to provide high drug loading content, and the modified GOQDs on the surfaces of the MONs were included to delay drug release in normal tissue. During light irradiation, the GOQDs produce 1O2 in a significantly high quantum yield [52,53,54], leading to the cleavage of 1O2-responsive bridges and the degradation of the nanoplatform (Scheme 1). The loaded anti-cancer drug is then released efficiently to destroy the tumor cells. Furthermore, degradability and clearance of this photo-responsive hollow degradable mesoporous organosilica nanoplatforms (HMONs@GOQDs) are appealing for clinical trials to overcome long-term toxicity.

Materials and methods

Materials

N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHS, 98%), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 99%), hexa-decyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, > 99.0%), Tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), 3-Chloro-1-propanol (98%), Anthraquinone (98%), Adogen 464, 3-Isocyanatopropyltriethoxysilane (95%) and (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) were purchased from Energy Chemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Ammonia (25.0–28.0%), nitric acid (65.0–68.0%) and sulfuric acid (95.0–98.0%) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai, China). MTT and RPMI-1640 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Other reagents were commercially available and used as received.

Breast cancer line 4T1 cells were originally obtained from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and cultured as monolayers in a RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a humidified incubator (5% CO2 in air, v/v).

Male nude mice (4 weeks old, ≈ 16 g) were fed in the specific pathogen free (SPF) animal room at 20 °C for 1 week prior to use.

Synthesis of graphene oxide quantum dots (GOQDs) and characterization

Graphene oxide quantum dots were synthesized by a modified strong-acid oxidation method. Typically, graphite powder (900 mg) were dispersed in concentrated sulfuric acid (100 mL, 95.0–98.0%), which was stirred for 1 h followed by sonication for 30 min. The resultant suspension was poured into a three-neck round-bottom flask which contained mixed acids (80 mL sulfuric acid (95.0–98.0%) and 60 mL nitric acid (65.0–68.0%). After 24 h of refluxing at 100 °C, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and a required amount of distilled water was slowly added. The pH was adjusted to ~ 8 with sodium bicarbonate. During this period, the reaction suspension was filtered for 3 times to remove the precipitated salt. Afterwards, the residual solution was collected by decantation with filter paper. The filtrate was dialysed in a dialysis bag (MWCO 3500 Da) against distilled water for more than 7 days to remove excess salt. The suspension was freeze-dried to obtain GOQDs powder with a yield of ca. 5%.

Synthesis of 9,10-dialkoxyanthracene (DN), possessing triethoxysilyl groups (DN precursor)

Briefly, 10 g 3-Chloro-1-propanol and 60 g sodium iodide were added into 100 mL acetone, the mixture was heated to 60 °C under nitrogen for 24 h, after filtration and evaporation, a 1:1 mixture of diethyl ether-hexane (100 mL) was added and stirred for 10 min at 25 °C and then filtered. The solution was washed with a dilute sodium thiosulfate solution followed by water and then brine. After the evaporation of organic solution, 3-Iodo-1-propanol was achieved. Yield 12.8 g, 67%; 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ (ppm): 3.73 (t, 2H, CH2OH), 3.28 (t, 2H, CH2I), 2.07 (m, 2H, CH2CH2CH2).

9,10-Anthraquinone (2.57 g), Na2S2O4 (4.3 g) and Adogen 464 (4.64 g) were added into nitrogen-saturated water (150 mL) and CH2Cl2 (150 mL). After stirring for 5 min at 25 °C, NaOH (4.94 g) was added, and then 3-iodo-1-propanol was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred for 12 h at 25 °C. Then the phases were separated and the organic phase was washed with water for 3 times. The solution volume was reduced to 40 mL in a rotary evaporator and the product was precipitated overnight at − 20 °C. The solid was purified by column chromatography with a mixture of ethyl acetate-CH2Cl2 (1/4, v/v). Yield 1.13 g, 28%; 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 8.24 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.2 Hz, 4H, anthracene), 7.52 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.2 Hz, 4H, anthracene), 4.63 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H, CH(O)), 4.18 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H, OCH2CH2), 3.76 (m, CH2CH2OH, 4H), 2.11 (m, CH2CH2CH2, 4H,).

9, 10-Bis(3-hydroxypropyloxy)anthracene (0.5 g), 3-Isocyanatopropyltriethoxysilane (0.38 g) and Triethylamine (0.155 g) were added into 100 mL ethanol. Then the mixture was refluxed at 80 °C for 12 h. and the product was purified by column chromatography with a mixture of ethyl acetate-CH2Cl2 (1/4, v/v). Yield 0.75 g, 85.2%.

Synthesis of DN group based hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles (HMONs)

DN group based hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles (HMONs) was synthesized according to the reported procedure [55]. Briefly, CTAB aqueous solution (5 g, 10 wt %) and TEA aqueous solution (0.2 g, 10 wt %) were mixed (pH = 9–10), the solution was then stirred in an oil bath at 95 °C for 10 min before 1 mL of TEOS was added dropwise. After 1 h, the silica core was generated. 0.25 mL TEOS and 0.25 g DN precursor were then added and the mixture was heated to 60 °C and stirred for 4 h. And the product was collected by centrifugation and washed with ethanol three times. To remove the silica core, the solid was redispersed in 100 mL water, and 2 mL ammonia (25.0–28.0%) were added, and the etching process lasted for 3 h at 95 °C. And HMONs were finally collected by centrifugation and washed with water.

Synthesis of photo-responsive biodegradable hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoplatforms (HMONs@GOQDs)

9 mg HMONs were dispersed in 5 mL ethanol, then 0.5 mL of (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES) was added. The obtained suspension was stirred for 24 h at 25 °C and collected by centrifugation, washed with ethanol several times and dried under vacuum to give HMONs-NH2. GOQDs aqueous solution (1 mg mL−1, 2 mL) was mixed with EDC (20 mg), NHS (40 mg) and 2 mL H2O, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 25 °C. Then the HMONs-NH2 aqueous solution (3 mg mL−1, 3 mL) were added to stir for another 12 h. HMONs@GOQDs nanohybrids were extracted with centrifugation and then washed with water for 3 times.

To prepare DOX-HMONs@GOQDs, GOQDs aqueous solution (1 mg mL−1, 2 mL) was mixed with EDC (20 mg), NHS (40 mg) and 2 mL H2O, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 25 °C. Then the HMONs-NH2 aqueous solution (3 mg mL−1, 3 mL) and DOX solution (5 mg mL−1 in DMSO, 200 µL) were added to stir for another 12 h. DOX-HMONs@GOQDs were extracted with centrifugation and then washed with water for 3 times. The DOX loading efficiency was calculated as follows:

where C0 and V0 are the concentration and volume of the added DOX, respectively, and Ct and Vt are the concentration and volume of free DOX after the centrifugation and washing, respectively.

Degradation evaluation of HMONs@GOQDs

To determine the structural evolution of HMONs@GOQDs under light irradiation, HMONs@GOQDs were dispersed in simulated body fluid (SBF) at 37 °C under slow stirring. Then the solution was irradiated with a Violet Blue Laser (365 nm, 0.8 W m−2) for 10 min at 30 min interval. The partially degraded HMONs@GOQDs was collected by centrifugation and directly observed by TEM characterization. Also the particle-size distribution of HMONs@GOQDs and supernatant was further analyzed by means of dynamic light scattering (DLS).

Degradation assay of HMONs@GOQDs at cell level

To study the intracellular degradation behavior of HMONs@GOQDs, HMONs@GOQDs (100 μg mL−1 in PBS, pH 7.4) were co-incubated with 4T1 cells, and then irradiated by light for 10 min at 30 min interval. After different incubation durations, the cells were harvested, fixed, and sectioned for bio-TEM characterization.

In vitro cytotoxicity

4T1 cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates at 1 × 104 per well incubated overnight at 3 °C in a humidified incubator, and then incubated with HMONs@GOQDs or DOX-HMONs@GOQDs at certain concentrations for 4 h. After removal of nanoparticles, cells were transferred into fresh media and irradiated by light for certain times. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C for additional 24 h before the standard methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT, Sigma Aldrich) assay.

In vivo experiments

To develop the tumor model, 4T1 cells (1 × 106) suspended in 50 μL of PBS were subcutaneously injected into the leg of each male athymic nude mice (4 weeks old). Then mice were divided into three groups (n = 4 per group) for various treatments: (1) ca. 50 μL of Saline + light; (2) DOX-HMONs@GOQDs; (3) DOX-HMONs@GOQDs + light (once every 2 d at a 5 mg kg−1 DOX-equivalent dose), and the light (365 nm, 0.8 W m−2) were conducted for 12 h after the injection (30 min/12 h, 2 min intervals for each 1 min irradiation). The tumor size were measured by a caliper every other day and calculated as the volume = (tumor length) × (tumor width)2/2. And the relative tumor volumes were calculated as V/V0 (V0 was the initial tumor volume).

Results and discussion

We synthesized the DN-based precursor according to the route outlined in Scheme 2. The chemical structure of the precursor was confirmed by 1HNMR spectroscopy, as shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

We synthesized the HMONs via sol–gel methods using SiO2 as the hard template based on a “structure difference-based selective etching” strategy [55]. The MONs layer was readily coated on the surface of the silica template owing to its similarity to tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) in the formation of the silica core. After the etching process, HMONs with high dispersity and well-defined hollow mesoporous structures were obtained. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images shown in Fig. 1a, b and Additional file 1: Fig. S2 confirm the hollow structure of HOMs. The mesoporous structure was also confirmed by the N2 absorption–desorption isotherms. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area of the HMONs was 425.662 m2 g−1, and the pore size was distributed at ~ 3.94 nm (Fig. 1c, d, respectively). The high surface area is beneficial to the drug-loading capacity, and the mesopores enable drug loading and release.

Characterization of the organosilica nanoparticles (HMONs). a Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the HMONs; b transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the HMONs; c N2 adsorption and desorption pattern of the HMONs; d pore size distributions of the HMONs; e Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum of the HMONs; and f thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves of the HMONs

To demonstrate the presence of DN groups in the HMONs shells, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra was carried out. As shown in Fig. 1e. the peak located at 1534 cm−1 is attributable to the C=C of the anthracene group, and the incorporation of organic bridges is revealed by νN–H at 3079 cm−1 and νC=O at 1691 cm−1, as well as by aliphatic and aromatic C-H stretching modes. The high degree of condensation of the siloxanes is confirmed by the shift of νSi–O at 1134 cm−1. We also used TGA to demonstrate the high organic content of the nanocomposites. The two significant weight losses presented at 220 and 400 °C were attributable to the thermal decomposition of the aliphatic chains and anthracene groups in the organic bridges, respectively, resulting in a total weight loss of 31%.

GOQDs are novel quantum dots, which have received considerable attention because of their excellent optical properties, favorable chemical stability, and low toxicity. They also provide a good platform for the production of 1O2 with a sufficiently high quantum yield for photodynamic therapy. Furthermore, GOQDs are easily modified due to the abundant hydroxyl and carboxyl groups on their surfaces [56,57,58,59]. Therefore, the GOQDs were prepared. First, we oxidized graphite powder in concentrated H2SO4 and HNO3. The particle size of the powder decreased dramatically after alkali treatment, and we isolated the resulting ultrafine GOQDs by dialysis [60]. As shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S3a, the GOQDs were approximately 10 nm in size. The emission spectrum of the GOQDs excited by 375-nm light also demonstrated the successful synthesis (Additional file 1: Fig. S3b). Under light irradiation, the GOQDs could transfer the photon energy to 3O2 leading to the generation of 1O2, and to assess the ability of GOQDs to generate 1O2, 9,10-anthracenediyl-bis(methylene) dimalonic acid (ABDA) was used as the trapping agent [61]. As illustrated in Additional file 1: Fig. S7, the absorbance of the ABDA decreased gradually with prolonged irradiation time, indicating the degradation of ABDA by 1O2 generated by GOQDs. The absorption intensity of the ABDA decreased to approximately 70% after irradiation at 365 nm (0.8 W/cm2) [53] for 10 min. In addition, the Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green (SOSG) measurements shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S8 also confirms the good 1O2 generation efficacy of GOQDs.

To coat the surface of the HMONs with GOQDs, we first modified the HMONs with amino groups using aminopropyltriethoxysilane via the Si–OH groups on their surfaces. We then activated the GOQDs using EDC/NHS chemistry, and attached them to the surfaces of the HMONs by direct covalent bonds. The resultant HMONs@GOQDs were characterized by SEM, TEM, dynamic light scattering (DLS), and UV–vis absorption analysis.

The HMONs@GOQDs retained their spherical morphology after the coating process. Furthermore, they had good dispersibility in aqueous solution owing to their abundant –OH and –COOH groups, and retained their high dispersion stability in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), even after 6 h (Additional file 1: Fig. S4). The high dispersibility of the HMONs@GOQD particles is apparent from the SEM image of a diluted sample (Additional file 1: Fig. S5), and could be further improved by surface modification with polyethylene glycol [62]. However, because the contrast arising from GOQDs is much lower than that from HMONs, it is difficult to directly observe the conjugation between the HMONs and GOQDs (Fig. 2a, b). The DLS of the HMONs and HMONs@GOQDs confirms the conjugation, as shown in Fig. 2c; the difference in particle size was entirely due to the coating of the GOQDs. The DLS of the HMONs@GOQDs also confirmed their favorable dispersity in aqueous solution. The UV–vis spectra of the GOQDs, HMONs, and HMONs@GOQDs are shown in Fig. 2d; the new absorption peak at 210–220 cm−1 attributable to HMONs@GOQDs proves successful conjugation owing to the presence of the characteristic GOQD peaks. We also determined the carbon contents of the HMONs and HMONs@GOQDs using a CHNS/O analyzer (PE 2400 II, Perkin Elmer, USA); the obtained carbon contents were 23.8 wt % and 32.9 wt %, respectively. This increased carbon content further confirmed the presence of GOQDs. The weight percentage of GOQDs to HMONs was calculated to be approximately 8.3 wt %. The BET surface area of the HMONs@GOQDs was 527.446 m2/g (Additional file 1: Fig. S6), which was higher than that of HMONs.

Characterization of HMONs@GOQDs. a Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the HMONs@GOQDs; b transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the HMONs@GOQDs; c size distribution of the organosilica nanoparticles (HMONs) and HMONs@GOQDs; d UV–vis adsorption of the graphene oxide quantum dots (GOQDs), HMONs, and HMONs@GOQDs; e percentages of DOX released from DOX-HMONs and DOX-HMONs@GOQDs with or without light irradiation

The production of 1O2 by HMONs@GOQDs was also investigated, and the reduced absorbance of ABDA confirmed that coating with GOQDs did not inhibit the generation of 1O2. We also confirmed the production of 1O2 by GOQDs using free HMONs as a control (Additional file 1: Fig. S7).

To study the drug loading and release profiles of HMONs@GOQDs, we used DOX as a model drug, and extracted it from doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX·HCl) according to the procedure reported previously [63]. DOX-HMONs@GOQDs was obtained by adding DOX solution (5 mg/mL in dimethyl sulfoxide) during the coating procedure. As shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S9, the FTIR spectra of HMONs@GOQD, free DOX and DOX-HMONs@GOQDs were studied. The Si–OH groups of HMONs and -OH groups of GOQDs involved in adsorption interactions with water molecules produce the broad band around 3500-3000 cm−1. It overlaps the absorption peak related to the N–H stretching vibrations attributed to DN-based precursor and the chemical linkage between HMONs and GOQDs, the new peaks at 1567 cm−1 was attributable to the C = C of the GOQDs. Compared with HMONs@GOQDs, the new absorption peak at 1741 cm−1 of DOX-HMONs@GOQDs confirmed the successful physical adsorption of DOX. To evaluate the drug-loading capacity, we determined the concentrations of DOX before and after the loading process using a fluorescence spectrophotometer; the capacity was 112 ± 6 mg of drug per gram of HMONs@GOQDs. This high drug-loading capacity and efficiency (approximately 82%) due to the hollow structure will be beneficial for chemotherapy.

The HMONs@GOQDs are designed to be degraded by light irradiation, enabling the efficient release of the loaded cargo. To confirm this profile, we dispersed the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs in PBS buffer, and determined the concentrations of DOX after various illumination periods. As shown in Fig. 2e, less than 5% of the DOX was released after 3 h without any stimulus because GOQDs blocked the mesopores of HMONs. In contrast, following light irradiation there was a large increase in release (> 80% in 3 h), which was probably due to the degradation of HMONs by light. We also evaluated the release capability of the DOX-loaded free HMONs, and found that their release efficiency was much lower than that of the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs because the free HMONs were nondegradable.

The degradation mechanism of HMONs@GOQDs was illustrated as Scheme 3. When irradiated with light, GOQDs produce 1O2, the DN groups in the in the shells of the HMONs would bind 1O2 efficiently and then react with 1O2 via the highly favorable [4 + 2] cycloaddition mechanism, forming stable endoperoxides which would spontaneously decompose in the follow-up proton-catalyzed reaction with the formation of products 9,10-anthraquinone (AQ), leading to the complete degradation of the HMONs [64].

To confirm this change, we mixed an ethanol solution of the DN precursor with the GOQDs, and irradiated it with light (365 nm, 0.8 W/m2) for various periods. The resulting UV–vis absorption spectra are shown in Fig. 3a. During light illumination for 0 to 30 min, the UV–vis absorption of the DN precursor decreased significantly with the generation of 1O2, confirming that the DN precursor was altered in the presence of 1O2.

Degradation of HMONs@GOQDs. a UV–vis adsorption of the 9,10-dialkoxy-anthracene (DN) precursor following light irradiation for various periods; b–e (TEM images and size distribution of HMONs@GOQDs after various irradiation periods showing the structural evaluation of HMONs@GOQDs (12, 24, and 48 h); and f size distribution of the supernatant after centrifugation

The degradation of the developed nanosystem is of great significance in terms of its suitability as a drug carrier in a clinical context. We used TEM to monitor the structural evolution of HMONs@GOQDs during the degradation process stimulated by light irradiation (30 min per 12 h) over various periods (Fig. 3b-d). There was significant degradation and the nanosized particles were completely degraded after 48 h. We also recorded the particle-size distribution after 48 h (Fig. 3f). Following centrifugation, we collected a drop of the supernatant of the HMONs@GOQDs suspension, and further confirmed the presence of small fragments after exposure to light by means of DLS analysis (Fig. 3e). These results indicate that the HMONs@GOQDs are degraded by light irradiation, which should enable the efficient release of the loaded cargo. We also irradiated free HMONs with light for 48 h, and the resulting TEM image is shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S10. The small change in the structure of the HMONs further confirmed that the degradation of the HMONs@GOQDs was caused by photo-induced 1O2 generation. This observation also indicates that the nanosized particles will be safely excreted by the body once they have completed drug delivery.

We further evaluated the degradation behavior and structural evolution of HMONs@GOQDs in cells. After co-incubating the HMONs@GOQDs with 4T1 cancer cells for 4 h, we irradiated the culture with light (365 nm, 0.8 W m−2, 30 min per 12 h, 2-min intervals for each 1-min irradiation). We harvested the cells after various periods, fixed them, and cut the resulting samples into ultrathin sections for bio-TEM investigation. As shown in Fig. 4a, the HMONs@GOQDs were efficiently endocytosed into the cancer cells; the hollow structures are clearly visible, and a small number of nanoparticles have degraded. Significant degradation is visible in Fig. 4b, and there are multiple amorphous morphologies. It should be noted that the vast majority of nanosized particles disappeared, demonstrating the complete degradation of the HMONs@GOQDs. The in vitro assays in both PBS solution and under intracellular conditions demonstrate the light-responsive degradation profile of the HMONs@GOQDs, which could potentially guarantee their controlled degradation in vivo.

To confirm the biocompatibility of the HMONs@GOQDs, we first incubated the 4T1 cells with various concentrations of the HMONs@GOQD nanocarriers in PBS for 24 h, and determined the viabilities of the cells. As shown in Fig. 5a, the HMONs@GOQDs had very low cytotoxicity (cell viability > 90% after incubation for 24 h), even at a high dosage concentration (160 μg/mL). The results prove that both GOQDs and HMONs are biocompatible and nontoxic, which are necessary for further biomedical applications. We also incubated the 4T1 cells with various concentration of the original DN-based precursor in PBS for 24 h, and the resulting low cytotoxicity further confirmed the biocompatibility of the HMONs@GOQDs (Additional file 1: Fig. S11).

In vitro experiments on HMONs@GOQDs and DOX-HMONs@GOQDs. a In vitro cell viability of HMONs@GOQDs at various concentrations; b time-dependent cellular internalization of DOX-HMONs@GOQDs in 4T1 cells after incubation for 1 or 2 h; c phototoxicity of cells incubated with free HMONs@GOQDs, DOX-HMONs, or DOX-HMONs@GOQDs with or without laser irradiation

The uptake of HMONs@GOQDs by the cells demonstrated the nanocarriers’ ability to deliver drugs intracellularly. We investigated the distribution of the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs in the 4T1 cells using a fluorescence microscope to detect the fluorescence of DOX and GOQDs. It was obvious that the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs were efficiently taken up by cells (Fig. 5b).

The degradation of HMONs@GOQDs under light irradiation causes the leakage of the loaded drug at the molecular level, resulting in the destruction of the tumor cells. We incubated various concentrations of the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs with the 4T1 cells for 4 h, removed the excess nanoparticles, and further incubated the cells for 24 h in the dark. Viability was evaluated using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay with or without light irradiation. We used 4T1 cells treated with saline and DOX-HMONs under light irradiation as control groups. Compared to the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs in the absence of light irradiation and the control groups, the irradiated DOX-HMONs@GOQDs has significantly enhanced cytotoxicity with regard to the cancer cells. This further confirmed the photo-controlled release and significant accumulation of DOX inside the cells owing to the degradation of the HMONs@GOQDs. The distribution of DOX was further demonstrated using co-localization fluorescence measurements after 4T1 cells were stained with DAPI. As shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S12, the fluorescence of DOX was mainly distributed in cytoplasm without light irradiation and nucleus with light irradiation, confirming the DOX leakage form the nanocarriers.

We also incubated the 4T1 cells with free HMONs@GOQDs, and the light-induced production of 1O2 also resulted in cytotoxicity with regard to the cancer cells. However, this cytotoxicity was much lower than that of light-stimulated DOX-HMONs@GOQDs owing to the low content of GOQDs. Therefore, the cytotoxicity of the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs was mainly caused by the significant accumulation of DOX resulting from the degradation of the HMONs.

It is worth noting that nano-sized HMONs@GOQDs can accumulate passively in tumor cells through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, and 1O2 is only generated during light irradiation. Therefore, the generation of 1O2 does not have a toxic effect on normal tissues [52, 61].

To study the antitumor activity of the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs during light irradiation in vivo, we randomly divided male athymic nude mice bearing 4T1 cells into four groups: a control group, a light only group, a free DOX-HMONs@GOQDs group, and a DOX-HMONs@GOQDs + light group. The DOX dosage was equivalent to the clinical dosage given to patients (5 mg kg−1), and the concentration of DOX was ca. 1.6 mg mL−1. Our estimate of therapeutic efficiency was based on the change in tumor volume. As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the light-irradiated DOX-HMONs@GOQDs significantly inhibited tumor growth, whereas tumor growth was not affected in the light irradiation only and free DOX-HMONs@GOQDs groups. Photographs of the tumors at the end of each treatment also revealed that the tumors were smaller in the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs + light group than in the other three groups (Fig. 6b). These results suggested that the tumor cells are able to take up the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs via an endocytosis pathway, and the loaded DOX could be released from the HMONs@GOQDs under light irradiation, and they further confirmed the photo-responsive degradation profile of HMONs@GOQDs. We also used male athymic nude mice bearing 4T1 cells—which had been treated with a mixture of the DN-based precursor and GOQDs—as a control group. The GOQDs, the original DN-based precursor, and the degradation products did not inhibit tumor growth. And then another group was received with free DOX at an equivalent DOX dose of 5 mg/kg, free DOX also could inhibit tumor growth, however, the administration of DOX-HMONs@GOQDs + light exhibited much higher tumor-inhibition effect compared to free DOX, further confirming that the significant effects in the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs + light group were caused by accelerated drug release (Additional file 1: Fig. S13). In addition, we fixed tumor cells from the tumor tissues, and cut them into ultrathin sections for bio-TEM investigation at 12 h after treatment injection. The HMONs@GOQDs were clearly visible in the cancer cells (Additional file 1: Fig. S14), indicating that the administrated nanoparticles did find their way into those cells in vivo. As shown in Fig. 6c, each mouse retained its weight well over the entire treatment period, indicating that both the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs and the other treatments would be safe for topical in vivo applications. To further confirm the safety of the treatments, we collected the major organs and subjected them to haemotoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. As shown in Fig. 6d, treatment with DOX-HMONs@GOQDs and light had little impact on the liver or on the other major organs.

In vivo antitumor efficacy of DOX-HMONs@GOQDs. a Growth curves of 4T1 tumors in each group; b photographs of tumors at the end of each treatment; c changes in the body weights of the mice over the treatment period; d haemotoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in the normal tissue group (the control) and the DOX-HMONs@GOQDs group

Conclusions

In conclusion, we developed novel photo-responsive biodegradable mesoporous organosilica nanoplatforms (HMONs@GOQDs) for anticancer drug delivery. The HMONs in the HMONs@GOQDs are based on 1O2-responsive DN-bridged organoalkoxysilanes, and degrade when irradiated with light owing to the GOQDs on their surfaces. The well-defined hollow mesoporous structures of the HMONs@GOQDs provide high drug-loading capacity, and photo-responsive degradation endows the nanoplatforms with photo-controlled drug release profiles. We carried out in vitro and in vivo experiments, which demonstrated the excellent therapeutic efficacy of the HMONs@GOQDs. Moreover, the degradability and clearance of the nanoplatforms avoid long-term toxicity, thereby qualifying them for cancer therapy clinical trials. However, short wavelength light (365 nm) does not readily penetrate the thick tissues of human patients. Nevertheless, the as-prepared HMONs@GOQDs have extensive application potential for cutaneous tumor therapy. Moreover, nitrogen-doped GOQDs or upconversion materials might be used to increase the range of light adsorption and expand the applicability of the HMONs@GOQDs in the future.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Manjelievskaia J, Brown D, McGlynn KA, et al. Chemotherapy use and survival among young and middle-aged patients with colon cancer. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:452–9.

Sobrero A, Grothey A, Iveson T, et al. The hard road to data interpretation: 3 or 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III colon cancer? Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1099–107.

Grothey A, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1177–88.

Turner MC, Farrow NE, Rhodin KE, et al. Delay in adjuvant chemotherapy and survival advantage in stage III colon cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226:670–8.

Jiang W, Von Roemeling CA, Chen Y, et al. Designing nanomedicine for immuno-oncology. Nat Biomed Eng. 2017;1:0029.

Jiang W, Yuan H, Chan CK, et al. Lessons from immuno-oncology: a new era for cancer nanomedicine? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:369.

Zhu F, Tan G, Zhong Y, et al. Smart nanoplatform for sequential drug release and enhanced chemo-thermal effect of dual drug loaded gold nanorod vesicles for cancer therapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2019;17:44.

Nel A, Ruoslahti E, Meng H. New insights into “permeability” as in the enhanced permeability and retention effect of cancer nanotherapeutics. 2017;11:9567.

Wang L, Huang J, Chen H, et al. Exerting enhanced permeability and retention effect driven delivery by ultrafine iron oxide nanoparticles with T1–T2 switchable magnetic resonance imaging contrast. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4582–92.

Iyer AK, Khaled G, Fang J, et al. Exploiting the enhanced permeability and retention effect for tumor targeting. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:812–8.

Ehlerding EB, Chen F, Cai W. Biodegradable and renal clearable inorganic nanoparticles. Adv Sci. 2016;3:1500223.

Croissant JG, Fatieiev Y, Khashab NM. Degradability and clearance of silicon, organosilica, silsesquioxane, silica mixed oxide, and mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1604634.

Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, et al. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1165.

Yang S, Fan J, Lin S, et al. Novel pH-responsive biodegradable organosilica nanoparticles as drug delivery system for cancer therapy. Colloids Surf, A. 2020;585:124133.

Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, et al. Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev. 2016;116:2602–63.

Kulkarni RK, Moore EG, Hegyeli AF, et al. Biodegradable poly (lactic acid) polymers. J Biomed Mater Res. 1971;5:169–81.

Martin O, Averous L. Poly (lactic acid): plasticization and properties of biodegradable multiphase systems. Polymer. 2001;42:6209–19.

Li X, Chu CL, Liu L, et al. Biodegradable poly-lactic acid based-composite reinforced unidirectionally with high-strength magnesium alloy wires. Biomaterials. 2015;49:135–44.

Mattana G, Briand D, Marette A, et al. Polylactic acid as a biodegradable material for all-solution-processed organic electronic devices. Org Electron. 2015;17:77–86.

Dunne M, Corrigan OI, Ramtoola Z. Influence of particle size and dissolution conditions on the degradation properties of polylactide-co-glycolide particles. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1659–68.

Jain RA. The manufacturing techniques of various drug loaded biodegradable poly (lactide-co-glycolide)(PLGA) devices. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2475–90.

Pavanetto F, Genta I, Giunchedi P, et al. Evaluation of spray drying as a method for polylactide and polylactide-co-glycolide microsphere preparation. J Microencapsul. 1993;10:487–97.

Xie H, Gursel I, Ivins BE, et al. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides adsorbed onto polylactide-co-glycolide microparticles improve the immunogenicity and protective activity of the licensed anthrax vaccine. Infect Immun. 2005;73:828–33.

Singh M, Kazzaz J, Ugozzoli M, et al. Charged polylactide co-glycolide microparticles as antigen delivery systems. Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:483–91.

Jia WJ, Gu YC, Gou ML, et al. Preparation of biodegradable polycaprolactone/poly (ethylene glycol)/polycaprolactone (PCEC) nanoparticles. Drug Deliv. 2008;15:409–16.

Saez A, Guzman M, Molpeceres J, et al. Freeze-drying of polycaprolactone and poly (d, l-lactic-glycolic) nanoparticles induce minor particle size changes affecting the oral pharmacokinetics of loaded drugs. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50:379–87.

Chawla JS, Amiji MM. Biodegradable poly (ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles for tumor-targeted delivery of tamoxifen. Int J Pharm. 2002;249:127–38.

Ferrari R, Yu Y, Morbidelli M, et al. ε-Caprolactone-based macromonomers suitable for biodegradable nanoparticles synthesis through free radical polymerization. Macromolecules. 2011;44:9205–12.

Kagan CR, Mitzi DB, Dimitrakopoulos CD. Organic-inorganic hybrid materials as semiconducting channels in thin-film field-effect transistors. Science. 1999;286:945–7.

Xing G, Mathews N, Sun S, et al. Long-range balanced electron-and hole-transport lengths in organic-inorganic CH3NH3PbI3. Science. 2013;342:344–7.

Sellinger A, Weiss PM, Nguyen A, et al. Continuous self-assembly of organic–inorganic nanocomposite coatings that mimic nacre. Nature. 1998;394:256.

Gomez-Romero P. Hybrid organic–inorganic materials—in search of synergic activity. Adv Mater. 2001;13:163–74.

Dolbecq A, Dumas E, Mayer CR, et al. Hybrid organic–inorganic polyoxometalate compounds: from structural diversity to applications. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6009–48.

Haraguchi K, Takehisa T. Nanocomposite hydrogels: a unique organic–inorganic network structure with extraordinary mechanical, optical, and swelling/de-swelling properties. Adv Mater. 2002;14:1120–4.

Wight AP, Davis ME. Design and preparation of organic–inorganic hybrid catalysts. Chem Rev. 2002;102:3589–614.

Zou H, Wu S, Shen J. Polymer/silica nanocomposites: preparation, characterization, properties, and applications. Chem Rev. 2008;108:3893–957.

Yang S, Chen S, Fan J, et al. Novel mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles with ferrocene group for efficient removal of contaminants from wastewater. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;554:565–71.

Reynhardt JPK, Yang Y, Sayari A, et al. Periodic mesoporous silica-supported recyclable rhodium-complexed dendrimer catalysts. Chem Mater. 2004;16:4095–102.

Wang ZM, Wang W, Coombs N, et al. Graphene oxide–periodic mesoporous silica sandwich nanocomposites with vertically oriented channels. ACS Nano. 2010;4:7437–50.

Peng H, Tang J, Yang L, et al. Responsive periodic mesoporous polydiacetylene/silica nanocomposites. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5304–5.

Olkhovyk O, Jaroniec M. Periodic mesoporous organosilica with large heterocyclic bridging groups. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:60–1.

Landskron K, Hatton BD, Perovic DD, et al. Periodic mesoporous organosilicas containing interconnected [Si (CH2)]3 rings. Science. 2003;302:266–9.

Wang X, Chen H, Zhang K, et al. An intelligent nanotheranostic agent for targeting, redox-responsive ultrasound imaging, and imaging-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound synergistic therapy. Small. 2014;10:1403–11.

Vivero-Escoto JL, Taylor-Pashow KML, Huxford RC, et al. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanospheres with cleavable Gd(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: synthesis, characterization, target-specificity, and renal clearance. Small. 2011;7:3519–28.

Luo Z, Cai K, Hu Y, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles end-capped with collagen: redox-responsive nanoreservoirs for targeted drug delivery. Angew Chem. 2011;123:666–9.

Loving GS, Mukherjee S, Caravan P. Redox-activated manganese-based MR contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4620–3.

Ganta S, Devalapally H, Shahiwala A, et al. A review of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. J Control Release. 2008;126:187–204.

Cotí KK, Belowich ME, Liong M, et al. Mechanised nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nanoscale. 2009;1:16–39.

Fatieiev Y, Croissant JG, Julfakyan K, et al. Enzymatically degradable hybrid organic–inorganic bridged silsesquioxane nanoparticles for in vitro imaging. Nanoscale. 2015;7:15046–50.

Cheng X, Li D, Lin A, et al. Fabrication of multifunctional triple-responsive platform based on CuS-capped periodic mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles for chemo-photothermal therapy. Int J Nanomed. 2018;13:3661.

Shao T, Wen J, Zhang Q, et al. NIR photoresponsive drug delivery and synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy by monodispersed-MoS2-nanosheets wrapped periodic mesoporous organosilicas. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4:7708–17.

Liu Y, Xu Y, Geng X, et al. Synergistic targeting and efficient photodynamic therapy based on graphene oxide quantum dot-upconversion nanocrystal hybrid nanoparticles. Small. 2018;14:1800293.

Markovic ZM, Ristic BZ, Arsikin KM, et al. Graphene quantum dots as autophagy-inducing photodynamic agents. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7084–92.

Ge J, Lan M, Zhou B, et al. A graphene quantum dot photodynamic therapy agent with high singlet oxygen generation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4596.

Huang P, Qian X, Chen Y, et al. Metalloporphyrin-encapsulated biodegradable nanosystems for highly efficient magnetic resonance imaging-guided sonodynamic cancer therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:1275–84.

Zhu S, Zhang J, Qiao C, Tang S, Li Y, Yuan W, Li B, Tian L, Liu F, Hu R, Gao H, Wei H, Zhang H, Sun H, Yang B. Strongly green-photoluminescent graphene quantum dots for bioimaging applications. Chem Commun. 2011;47:6858–60.

Yao X, Tian Z, Liu J, Zhu Y, Hanagata N. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles capped with graphene quantum dots for potential chemo-photothermal synergistic cancer therapy. Langmuir. 2016;33:591–9.

Wu C, Wang C, Han T, Zhou X, Guo S, Zhang J. Insight into the cellular internalization and cytotoxicity of graphene quantum dots. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013;2:1613–9.

Nurunnabi M, Khatun Z, Huh KM, Park SY, Lee DY, Cho KJ, Lee Y-K. In vivo biodistribution and toxicology of carboxylated graphene quantum dots. ACS Nano. 2013;7:6858–67.

Pan D, Zhang J, Li Z, et al. Hydrothermal route for cutting graphene sheets into blue-luminescent graphene quantum dots. Adv Mater. 2010;22:734–8.

Wojtoniszak M, Rogińska D, Machaliński B, et al. Graphene oxide functionalized with methylene blue and its performance in singlet oxygen generation. Mater Res Bull. 2013;48:2636–9.

Qin Y, Chen LJ, Dong F, et al. Light-controlled generation of singlet oxygen within a discrete dual-stage metallacycle for cancer therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:8943–50.

Yang S, Chen D, Li N, et al. Hollow mesoporous silica nanocarriers with multifunctional capping agents for in vivo cancer imaging and therapy. Small. 2016;12:360–70.

Arian D, Kovbasyuk L, Mokhir A. 1,9-Dialkoxyanthracene as a 1O2-sensitive linker. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3972–80.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51802127), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20170239), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and Jiangsu Normal University scientific research fund (16XLR005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SY conceived of this work and drafted this manuscript. In addition, JF, ZZ and YW performed the preparation and characteristics of HMONs@GOQDs. JF, ZZ and SL helped with the biological study and performed the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the internationally accepted principles and Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Jiangsu Normal University and the experiment protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee of the Jiangsu Normal University. All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Additional figures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, J., Zhang, Z., Wang, Y. et al. Photo-responsive degradable hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoplatforms for drug delivery. J Nanobiotechnol 18, 91 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-020-00642-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-020-00642-1