Abstract

Background

Atherogenic dyslipidemia (AD) is a blood serum lipid profile abnormality characterized by elevation of triglycerides and reduced levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). It is associated with residual cardiovascular risk. This study evaluated and compared the risk profiles of patients with hypertriglyceridemia, low-HDL-C levels or AD, in order to understand, which lipid profile is associated with greater risk.

Methods

During the period of 2009–2016 a population of 92,373 Lithuanian adults (men 40–54 years old and women 50–64 years old) without overt cardiovascular disease were analyzed. Data of 25,746 patients (68.6% women and 31.4% men) with hypertriglyceridemia and/or low HDL-C low levels were collected and used for further statistical analysis.

Results

Participants with AD tend to have more unfavorable risk profile than participants with hypertriglyceridemia or low-HDL-C. AD tends to cluster with other atherogenic risk factors, such as arterial hypertension [odds ratio (OR) 1.96, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.87–2.01], smoking [OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.14–1.27], diabetes mellitus [OR 2.74, 95% CI 2.58–2.90], obesity [OR 2.92, 95% CI 2.78–3.10], metabolic syndrome [OR 22.27, 95% CI 20.69–23.97], unbalanced diet [OR 1,59, 95% CI 1.51–1.68], low physical activity [OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.71–1,89], CHD history in first degree relatives [OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.12–1.25] and total number of risk factors [OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.38–1.57].

Conclusion

AD is associated with more unfavorable cardiovascular risk profile than hypertriglyceridemia or low-HDL cholesterol levels. Once identified AD should require additional medical attention since it is an important factor of residual cardiovascular risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atherogenic dyslipidemia (AD) is a lipid abnormality defined as the presence of elevated triglycerides (TG) and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). It is known to increase the risk of coronary events in patients with or without CAD [1, 2] as well as silent myocardial infarction and silent CAD in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes [3]. Additional findings such as elevation of small dense low-density lipoprotein (sd-LDL) particles, elevated levels of apolipoprotein B (Apo-B), detection of large TG rich very low-density lipoproteins and oxidized LDL, as well as decreased number of small HDL particles contributes to AD vascular risk [4]. AD is a common lipid profile in patients with obesity, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease (CAD) [5,6,7,8]. It is not clear whether AD is associated with higher risk than hypertriglyceridemia or low-HDL alone. The aim of our study was to evaluate prevalence of AD, hypertriglyceridemia and low-HDL-C levels in middle-aged Lithuanian population and to compare cardiovascular risk profile of patients with these different lipid panel abnormalities, in order to understand which lipid profile is associated with higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors.

Methods

Our study is a part of the ongoing LitHiR Primary Prevention Program. It was launched in Lithuania in 2006, in reference to unfavorable situation of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in Lithuania, with an approval of the Local Research Ethics Committee. LitHiR program includes 40–54 years old men and 50–64 years old women without overt cardiovascular disease (CVD) from all regions of Lithuania. 94.8% (398/420) of all the primary care institutions participate in the project. During the period of 2009–2016 our study included 92,373 participants. Data of 25,746 patients with hypertriglyceridemia > 1.7 mmol/l and/or low-HDL-C (< 1.2 mmol/l for women and < 1 mmol/l for men) were collected and used for further statistical analysis. Serum total cholesterol (TC), calculated LDL-C, HDL-C, TG levels, non-HDL cholesterol, TG/HDL ratio, log TG/HDL index and plasma fasting glucose concentration were estimated. Patients’ blood samples were processed at the standardized laboratories in the participating centres. Cardiovascular risk profile of each participant was obtained. A detailed description of the LitHir program protocol is presented in Laucevicius et al. paper [9].

The overall cardiovascular risk was evaluated according to the SCORE (Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation) risk estimation system. Metabolic syndrome (MS) was assessed by the National Cholesterol Education Program ATP III modified criteria.

Participants were divided into three groups according to the components of AD: first group included adults with AD, which was considered if TG were > 1.7 mmol/l and HDL-C was < 1.2 mmol/l in women and < 1.0 mmol/l in men. The second group was composed of people with hypertriglyceridemia, which was considered if TG were > 1.7 mmol/l and HDL-C were > 1.2 mmol/l in women and > 1.0 mmol/l in men. The third group included men and women with low HDL-C, which was considered if HDL-C was < 1.2 mmol/l in women and < 1.0 mmol/l in men and TG were < 1.7 mmol/l. LDL-C levels did not impact division into groups.

Women with AD were divided into 50–54 (n = 1560), 55–59 (n = 1252) and 60–64 (n = 1268) year groups. Men were divided into 40–44 (n = 1264), 45–49 (n = 1043) and 50–54 (n = 1102) year old groups and their cardiovascular risk profile was assessed.

Statistics

Categorical variables were described through absolute frequencies and percentage, and continuous variables through mean and standard deviation (SD). Continuous variables were compared using T-test or the Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables were compared by carrying out the chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess factors associated with AD, hypertriglyceridemia and low-HDL-C. Variables considered in the multivariate analysis included low physical activity, unbalanced diet, smoking, arterial hypertension (AH), diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, CHD history in a first-degree relatives, MS and having more than 3 risk factors. All reported p-values are two-tailed. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. The SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) statistical package was used for all statistical calculations.

Results

Sample characteristics

During the period of 2009–2016 our study included 92,373 participants without overt cardiovascular disease. The average age of subjects was 52.15 ± 6.21 years. The sample consisted of 58.4% (n = 53,961) women and 41.6% (n = 38,412) men. Any type of dyslipidemia was diagnosed in 89.7% (n = 82,893) of the subjects.

Characteristics of subjects with different types of dyslipidemia

During this study, subjects were divided into three groups according to their lipid panel. In overall LitHiR population 25,746 participants had one of the following lipid abnormalities: AD– 29.1% (n = 7489, 54.5% of them were women and 45.5% men), hypertriglyceridemia 80.0% (n = 20,593, 50.7% women and 49.3% men) or low-HDL-C levels 20.0% (n = 5153, 60.8% women and 39.2% men). The prevalence of AD in LitHiR population (n = 92,373) was 8.1%, hypertriglyceridemia - 22.3% and low-HDL-C levels - 5.6%.

Cardiovascular risk profile of subjects with different types of dyslipidemia

Demographic, anthropometric and laboratory characteristics of participants with AD, hypertriglyceridemia and low-HDL-C levels groups are shown in Table 1. Participants in low-HDL-C group were statistically significantly older (52.41 ± 6.33 years) in comparison with other groups. Participants with AD tended to have higher prevalence of AH (69.0%), DM (22.6%), abdominal obesity (67.6%), MS (88.9%), unbalanced diet (71.0%), low physical activity (64.2%) and percentage of people having more than 3 risk factors (86.1%). In addition, prevalence of smoking (26.1%) and CHD in first degree relatives (29.1%) was higher in AD group than in low-HDL-C group. Participants in low-HDL group had more favorable risk profile: lower prevalence of DM (12.5%), AH (56.9%), MS (52.7%), smoking (22.3%), unbalanced diet (62.2%), low physical activity (56.5%). Participants in hypertriglyceridemia group had higher values of total cholesterol (6.74 ± 1.24 mmol/l), LDL-C (4.28 ± 1.16 mmol/l), HDL-C (1.45 ± 0.34 mmol/l), non-HDL cholesterol (5.29 ± 1.22 mmol/l) and SCORE index (2.27 ± 1.94) in comparison with other groups.

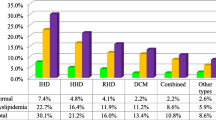

Characteristics of men and women with AD according to age

Analysis of participants with AD according to gender and age revealed that older women (60–64 years) with AD tend to have higher waist circumference (101.10 ± 13.23 cm), systolic blood pressure (141.56 ± 17.52 mmHg), TC (6.42 ± 1.26 mmol/l), LDL-C (4.19 ± 1.13 mmol/l), non-HDL-C (5.38 ± 1.25 mmol/l), serum glucose concentration (6.31 ± 2.10 mmol/l) and SCORE index (3.92 ± 2.35), as well as higher prevalence of low physical activity (70.7%), higher prevalence of AH (84.8%), DM (31.8%) and MS (96.0%) and higher percentage of people having more than 3 risk factors (93.1%). Older men (50–54 years) with AD tend to have lower TG (3.33 ± 2.11 mmol/l), higher blood pressure (systolic blood pressure - 137.78 ± 16.68 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure 85.81 ± 9.91 mmHg), serum glucose concentration (6.20 ± 2.16 mmol/l), SCORE index (3.40 ± 2.16), and percentage of people having more than 3 risk factors (84.9%), as well as higher prevalence of AH (65.9%), DM (23.5%) and MS (86.7%), and lower prevalence of CHD history in first degree relatives (24.4%) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Logistic regression of risk factors for different types of dyslipidemia

According to LitHiR database, all analyzed risk factors, including main risk factors such as DM (OR: 2.74, 95% CI: 2.58–2.90), AH (OR: 1.96, 95% CI 1.87–2.01), obesity (OR: 2.92, 95% CI: 2.78–3.10) and smoking (OR: 2.74, 95% CI: 2.58–2.90) were significantly associated with AD and hypertriglyceridemia according to logistic regression with univariate models (Table 2). There was no association between isolated low HDL-C levels and smoking, CAD history in the first degree relatives and unbalanced diet.

Further statistical analysis according to gender revealed that arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, metabolic syndrome, unbalanced diet and CHD history in first degree relatives were significantly associated with AD and isolated hypertriglyceridemia in both men and women. Unbalanced diet was significantly associated with low-HDL in men, however smoking did not show significant association with AD and low-HDL in men. There was significant association between unbalanced diet and low-HDL in women [OR: 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.17].

Discussion

The prevalence of AD (8.1%) was similar to expected values, since we analyzed middle aged population without overt cardiovascular disease. Other authors reveal that the prevalence of AD varies from, approximately, 5.7% in working population [10], 9.9% in primary prevention patients with at least one cardiovascular risk factor [11], 27.1% in primary prevention patients of moderate to very high risk [12] and up to even 40.0% in patients who underwent coronary angiography due to myocardial infarction or unstable angina [2].

Our study also shows that participants with isolated hypertriglyceridemia had higher SCORE index than participants with AD. However participants with AD seemed to have worse risk profile. It is important to note, that using SCORE index might underestimate patients cardiovascular risk in patients with AD.

Low-HDL-C and high-TG were associated with low physical activity. It can be explained by association with obesity and increased caloric intake which leads to overproduction of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (higher serum TG), increased expression of hepatic lipase and lower HDL-C [13]. This underlines a huge importance of lifestyle intervention (dietary restriction and increased exercise) in treating atherogenic dyslipidemia [14]. It has been reported that 5–10% weight loss can lower LDL-C by approximately 15% and TG approximately 20–30% and increase HDL-C approximately 8–10% [15]. According to our data women would benefit from weight loss the most, since unbalanced diet was strongly associated with AD in women (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.56–1.80).

The prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia (22.3%) was similar to expected values. For example prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia in primary prevention patients with at least one cardiovascular risk factor in EURICA study was 20.8% [11].

The role of serum triglycerides concentration as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease remains controversial: some studies claim that hypertriglyceridemia is an independent risk factor, some studies reveals no significant association with CHD. For example, 29 prospective studies, which included 262,525 participants revealed moderate and highly significant associations between TG levels and CHD, however the impact of TG decreased after adjusting other factors association substantially attenuated [16]. On the other hand, meta-analysis of 68 long-term prospective studies including 302,430 people revealed no significant association between TG and CVD [17]. However, the cross-sectional nature of our study did not allow us to identify causal relationship.

The pattern of TG concentration changes in men according to age were similar to ones reported in literature. It is known that TG concentration in men tends to increase progressively with age reaching peak values at the age of 40 to 50 years, and shows a slight decline thereafter. TG concentration in women increase throughout their lifetime [18, 19]. In our study men had highest TG at the age of 40–44 years and TG concentration was lower in older men. The elevation of TG concentration in women was similar in all age groups.

Despite the fact, that the prevalence of dyslipidemia in Lithuania is high (89.7%), the prevalence of low-HDL-C (5.6%) was unexpectedly low, since reported prevalence of low-HDL in primary prevention patients with at least one cardiovascular risk factors is 22.1% [11] and even 56.5% in PERU MIGRANT study [20].

Low-HDL concentration is an independent risk factor of CHD irrespective of sex, race and ethnicity [21]. It is inversely associated with weight, abdominal circumference, TG concentration, number of small dense LDL particles, systemic inflammatory response and smoking [22]. However, the evidence supporting cardio protective role of high HDL-C levels are lacking, since drugs with effect of increasing HDL-C (fibrates, CETP inhibitors and nicotine acid) have failed to show benefit in decreasing incidence of coronary events and mortality rates in patients on statin therapy [23,24,25]. Participants in low-HDL group showed more favorable risk profile than other groups, which contributes to the notion that the quality of HDL particles plays an important role in the pathogenesis of CHD and further studies are needed. Walter reported that plasma HDL-C levels decrease in males during adolescence and early adulthood, but in elder age they are unchanged or even slightly increased [26]. In contrast women’s HDL-C levels remains stable throughout their lifetime, however, menopause often causes a slight decrease in HDL-C concentration [27]. In our study the differences of HDL-C levels in different age groups of both men and women were statistically insignificant.

The cross-sectional nature of our study did not allow us to identify causal relationship.

Conclusion

Hypertriglyceridemia and low-HDL-C play an important role in residual CV risk profile. AD was associated with more unfavorable risk profile than hypertriglyceridemia or low-HDL cholesterol. AD was reported almost in one of ten adults without overt cardiovascular disease in Lithuania. Once identified AD should require additional medical attention.

References

Manninen V, Tenkanen L, Koskinen P, Huttunen JK, Mänttäri M, Heinonen OP, et al. Joint effects of serum triglyceride and LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol concentrations on coronary heart disease risk in the Helsinki heart study. Implications Treat Circ. 1992;85(1):37–45.

Arca M, Montali A, Valiante S, Campagna F, Pigna G, Paoletti V, et al. Usefulness of atherogenic dyslipidemia for predicting cardiovascular risk in patients with angiographically defined coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(10):1511–6.

Valensi P, Avignon A, Sultan A, Chanu B, Nguyen MT, Cosson E. Atherogenic dyslipidemia and risk of silent coronary artery disease in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016 [cited 2017 Oct 10];15. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4957891/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4957891/pdf/12933_2016_Article_415.pdf.

Manjunath CN, Rawal JR, Irani PM, Madhu K. Atherogenic dyslipidemia. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(6):969.

Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and International Association for the Study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5.

Austin MA, King MC, Vranizan KM, Krauss RM. Atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype. A proposed genetic marker for coronary heart disease risk. Circulation. 1990;82(2):495–506.

Alsheikh-Ali AA, Lin J-L, Abourjaily P, Ahearn D, Kuvin JT, Karas RH. Prevalence of low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with documented coronary heart disease or risk equivalent and controlled low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(10):1499–501.

Ninomiya JK, L’Italien G, Criqui MH, Whyte JL, Gamst A, Chen RS. Association of the metabolic syndrome with history of myocardial infarction and stroke in the third National Health and nutrition examination survey. Circulation. 2004;109(1):42–6.

Rinkūnienė E, Llaucevicius A, Petrulioniene Z, Dzenkeviciute V, Kutkienė S, Skujaitė A, et al. The prevalence of dislipidemia and its relation to other risk factors: a nationwide survey of Lithuania. Clin Lipidol. 2015;10:219–25.

Cabrera M, Sánchez-Chaparro MA, Valdivielso P, Quevedo-Aguado L, Catalina-Romero C, Fernández-Labandera C, et al. Prevalence of atherogenic dyslipidemia: association with risk factors and cardiovascular risk in Spanish working population. “ICARIA” study. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235(2):562–9.

Halcox JP, Banegas JR, Roy C, Dallongeville J, De Backer G, Guallar E, et al. Prevalence and treatment of atherogenic dyslipidemia in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in Europe: EURIKA, a cross-sectional observational study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017 [cited 2017 Nov 16];17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28623902, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5473961/.

Plana N, Ibarretxe D, Cabré A, Ruiz E, Masana L. Prevalence of atherogenic dyslipidemia in primary care patients at moderate-very high risk of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular risk perception. Clin E Investig En Arterioscler Publicacion Of Soc Espanola Arterioscler. 2014;26(6):274–84.

Kreisberg RA, Kasim S. Cholesterol metabolism and aging. Am J Med. 1987;82(1):54–60.

Van LG, Wauters MA, De IL. The beneficial effects of modest weight loss on cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord J Int Assoc Study Obes. 1997;21(Suppl 1):S5–9.

Vega GL, Grundy SM, Barlow CE, Leonard D, Willis BL, DeFina LF, et al. Association of triglyceride-to-high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio to cardiorespiratory fitness in men. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(6):1414–1422.e1.

Sarwar N, Danesh J, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson G, Wareham N, Bingham S, et al. Triglycerides and the risk of coronary heart disease: 10,158 incident cases among 262,525 participants in 29 western prospective studies. Circulation. 2007;115(4):450–8.

Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Perry P, Kaptoge S, Ray KK, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 2009;302(18):1993–2000.

Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, Brumm J, et al. Effects of Dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(22):2089–99.

Liu H-H, Li J-J. Aging and dyslipidemia: a review of potential mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;19:43–52.

Lazo-Porras M, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Málaga G, Gilman RH, Acuña-Villaorduña A, Cardenas-Montero D, et al. Low HDL cholesterol as a cardiovascular risk factor in rural, urban, and rural-urban migrants: PERU MIGRANT cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2016;246(Supplement C):36–43.

Brahm A, Hegele RA. Hypertriglyceridemia. Nutrients. 2013;5(3):981–1001.

Cooney MT, Dudina A, De Bacquer D, Wilhelmsen L, Sans S, Menotti A, et al. HDL cholesterol protects against cardiovascular disease in both genders, at all ages and at all levels of risk. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206(2):611–6.

Toth PP, Barter PJ, Rosenson RS, Boden WE, Chapman MJ, Cuchel M, et al. High-density lipoproteins: a consensus statement from the National Lipid Association. J Clin Lipidol. 2013;7(5):484–525.

Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis DP. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117 411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

Ip C, Jin D, Gao J, Meng Z, Meng J, Tan Z, et al. Effects of add-on lipid-modifying therapy on top of background statin treatment on major cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cardiol. 2015;191:138–48.

Gobal FA, Mehta JL. Management of dyslipidemia in the elderly population. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;4(6):375–83.

Walter M. Interrelationships among HDL metabolism, aging, and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(9):1244–50.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to thank Roma Puronaitė for helping with statistical data analysis.

Funding

This study is a part of the ongoing LitHiR Primary Prevention Program financed from the budget of Compulsory Health Insurance of Lithuania.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available, as the research is ongoing and further publications are being done.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK, ZP, AL, GM, VK, EP, JS, AS, UG and ES designed the study, participated in the collecting and analyzing of the data, writing and reviewing manuscript. MK and ER rewieved the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study was approved of the Local Research Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from each author, and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kutkiene, S., Petrulioniene, Z., Laucevicius, A. et al. Cardiovascular risk profile of patients with atherogenic dyslipidemia in middle age Lithuanian population. Lipids Health Dis 17, 208 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-018-0851-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-018-0851-0