Abstract

Background

Bacteroides fragilis is a part of the normal gastrointestinal flora, but it is also the most common anaerobic bacteria causing the infection. It is highly resistant to antibiotics and contains abundant antibiotic resistance mechanisms.

Methods

The antibiotic resistance pattern of 78 isolates of B. fragilis (22 strains from clinical samples and 56 strains from the colorectal tissue) was investigated using agar dilution method. The gene encoding Bacteroides fargilis toxin bft, and antibiotic resistance genes were targeted by PCR assay.

Results

The highest rate of resistance was observed for penicillin G (100%) followed by tetracycline (74.4%), clindamycin (41%) and cefoxitin (38.5%). Only a single isolate showed resistance to imipenem which contained cfiA and IS1186 genes. All isolates were susceptible to metronidazole. Accordingly, tetQ (87.2%), cepA (73.1%) and ermF (64.1%) were the most abundant antibiotic-resistant genes identified in this study. MIC values for penicillin, cefoxitin and clindamycin were significantly different among isolates with the cepA, cfxA and ermF in compare with those lacking such genes. In addition, 22.7 and 17.8% of clinical and GIT isolates had the bft gene, respectively.

Conclusions

The finding of this study shows that metronidazole is highly in vitro active agent against all of B. fragilis isolates and remain the first-line antimicrobial for empirical therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bacteroides fragilis is an anaerobic, Gram-negative bacteria and a part of the human gastrointestinal microbiota but can cause opportunistic infections in human. The genus Bacteroides accounts for about 25% of gastrointestinal tract (GIT) flora [1, 2]. Among various species of this genus and other endogenous anaerobic bacteria, Bacteroides fragilis (B. fragilis) has also been found as the most virulent and abundant opportunistic anaerobic bacterium isolated from clinical specimens [1, 3]. B. fragilis represents 1–2% of the normal flora of the gastrointestinal tract and, if dislocated into other anatomical sites, cause various infections such as abdominal infections, abscesses, skin and soft tissue infection, and bacteremia with a mortality rate of about 19% [1, 4]. Studies have further established that the enterotoxigenic B. fragilis (ETBF) strains are more pathogenic than non-toxigenic (NTBF) ones and they are associated with various diseases such as septicaemia, diarrhoea, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and colorectal cancer (CRC) [5, 6].

Several studies have further revealed that B. fragilis exhibits the highest antibiotic resistance and the most numerous antibiotic resistance mechanisms compared with other anaerobic bacteria in the GIT [7]. This not only makes it difficult to treat infections caused by B. fragilis, but also has the potential to act as a reservoir of antibiotic-resistant genes [8], leading to their transfer to other normal bacterial flora through integrated transposons, integrated genetic elements, as well as conjugative plasmids [9].

In this respect, different resistance patterns of this bacterium have been so far reported from different parts of the world. There have been reports of increased resistance to carbapenems and beta-lactams among B. fragilis isolates worldwide [6, 10,11,12,13]. Of note, the rate of resistance to metronidazole, as an effective antibiotic against anaerobic bacteria, is about 1%, but some reference laboratories have reported a resistance rate of up to 7.5% [14,15,16]. Moreover, the number of multidrug-resistant B. fragilis isolates has increased over the last decade [17,18,19]. Improper and excessive use of antibiotics without a doctor’s supervision are the reason for promotes bacterial resistance [20].

Despite this growing problem, few studies are reported about the rate of antibiotic resistance and the accordance of antibiotic resistance genes among B.fragilis strains from Iran. Therefore, in this study antibiotic resistance profiles of B. fragilis isolated from the GIT and clinical samples were evaluated using phenotypic and genotypic methods.

Materials and methods

Study population

The current cross-sectional study examined two populations, the patients, and the healthy controls. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Institute for Medical Research development in Iran (NO. 971329). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

The patient population included people suspected of having anaerobic infection hospitalized in different wards of Imam Khomeini Hospital of Tehran, and the healthy population included people with no history of GIT disease or antibiotic consumption in the past 3 months.

In the sampling process from the patients, 130 different clinical samples were collected from hospitalized patients in different wards of the hospital during 1 year (from August 2018 to August 2019). Sampling, culture and isolation of anaerobic bacteria were performed according to standard procedures [21].

In the sampling process from healthy individuals, 40 biopsies of the colorectal were collected by a physician during colonoscopy. To isolate B. fragilis, the biopsy sample was homogenized by mortar and pestle, and then 2–3 drops were inoculated on a plate containing Bacteroides Bile Esculin Agar (BBE) and Brucella Blood Agar (BBA) containing 5% sheep blood, vitamin K1 (0.5 mg/L) and hemin (5 mg/L) and cultured by isolation method. The cultivated plates were incubated for 48–72 h at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. The black-colored colonies on the BBE medium and the ones grown on the BBA medium (5–10 colonies) were subcultured on the BBA medium. Ultimately, after confirming the phenotypic features (growth only in anaerobic conditions, Gram morphology, positivity to esculin and catalase), the isolates were preserved at − 80 °C using 5% glycerol [21, 22].

.

Identification of B. fragilis

The anaerobic bacteria were phenotypically identified based on colony morphology, Gram staining, and differential tests such as catalase, indole, bile disc, and finally Vitek 2 system (Biomerieux, France). Two polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were also performed to amplify the 16 S rDNA gene fragment; the first reaction to confirm the B. fragilis group and the second reaction the B. fragilis species [23, 24]. The 16 S rDNA gene was sequenced for B. fragilis strains and then submitted to the GenBank sequence database.

Antibiotic susceptibility of B. fragilis isolates

The antibiotic susceptibility testing of B. fragilis isolates was performed by agar dilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [25]. The tested antibiotics included ampicillin/sulbactam, piperacillin/tazobactam, penicillin G, tetracycline, imipenem, meropenem, clindamycin, cefoxitin, and metronidazole. Different concentrations of the antibiotics were included in the BBA medium containing vitamin K1 (0.5 mg/l) and hemin (5 mg/l).

Moreover, 10 µl of microbial suspension with a density of 107 colony-forming unit (CFU) ml− 1 was placed onto the plates containing antibiotics to achieve a final dilution of 105 CFU per spot. Plate without the antibiotic or the bacterial suspension, was used as negative controls (NC).

The plates were also incubated for 48 h at 36 ºC under anaerobic conditions. The lowest antibiotic concentration that inhibits the appearance of bacterial growth, was determined as the MIC (Minimum inhibitor concentration). Resistance levels to different antibiotics obtained via the breakpoints recommended by the CLSI.

Identification of resistance genes

The presence of IS1186 and cfiA gene (associated with resistance to carbapenems), the cepA and cfxA genes (associated with resistance to beta-lactams), the ermF, ermB, and mefA genes (associated with resistance to clindamycin), the tetQ gene (associated with resistance to tetracycline) and the nim gene (associated with resistance to metronidazole) were determined by PCR in B. fragilis isolates [26]. In order to detect the bft gene using PCR, parts of this gene were amplified [27].

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The Chi-square test was performed to calculate significant differences between the presence of antibiotic resistance genes among resistant strains in comparison to non-resistant strains. Also, Mann-Whitney test was applied to examine significant differences of MIC value for each antibiotic class among isolates with resistance genes in compare with isolates lacking these genes. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

In this study, 130 clinical samples were collected in patient hospitalized in different part of the hospital. Frequency of samples according to clinical specimen type are shown in Fig. 1.

Cultivation results in 28 clinical samples (21.5%) were positive for anaerobic bacteria. The GenBank accession numbers of the 16 S rRNA gene for these bacteria were MN982885.1, MN955695.1, MN955694.1, MN955585.1, MN955548.1, MN955546.1, MN94720209.1, MN949555 M55.1, MN955544.1, MN954671.1, MN954561.1, MN954557.1, MN937266.1, MN937239.1, MN933933.1, and MN933926.1. B. fragilis (n = 22; 46.8%) was the most isolated species among 47 anaerobic bacteria. Table 1 shows the frequency of anaerobic bacteria isolated from clinical specimens.

From 40 colorectal tissue biopsies in healthy individuals, 56 B. fragilis isolates were identified in 24 specimens (60%). Resistance patterns of the B. fragilis isolates, reporting MIC50 and MIC90, are shown in Table 2. The B. fragilis isolates had the highest resistance rate to penicillin (100%), tetracycline (74.4%), clindamycin (41%) and cefoxitin (38.5%).

tetQ, ermF, ermB, cfiA, cepA, cfxA, mefA, nim genes and the insertion sequence IS1186 were further searched to evaluate antibiotic resistance by the PCR. Absolute and relative frequencies of resistance and insertion sequences genes are presented in Table 3.

In this study, tetQ (87.2%), cepA (73.1%) and ermF (64.1%) were the most abundant antibiotic-resistant genes. The nim and ermB genes were not detected in any of the isolates. The IS1186 sequence in the upstream region of the cfiA gene was detected in one isolate (1.3%); this isolate was also resistant to imipenem.

The presence of the cfxA and ermF genes were significantly higher in cefoxitin and clindamycin resistant isolates in compare with cefoxitin and clindamycin susceptible isolates (p = 0.001, 0.000).

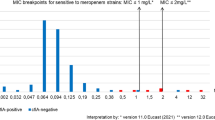

In addition, MIC values of penicillin, cefoxitin and clindamycin were significantly different among isolate with the cepA, cfxA and ermF genes in compare with isolates lacking these genes (p = 0.002, 0.000, 0.001) (Fig. 2).

In this study, the bft gene was observed in 22.7 and 17.8% of the clinical and colorectal isolates, respectively (Table 3).

Discussion

Bacteroidetes as a large community of gut microbiota can be isolated from human clinical specimens and lead to mixed anaerobic bacterial infections [3]. Antibiotic-resistant genes also play important roles in the antibiotic resistance of B. fragilis and cause unsuccessful antibacterial therapy. In this study, we have evaluated the prevalence of resistance genes and antibiotic resistance profile of B. fragilis using phenotypic approaches and amplification of genes of interest.

In this study, B. fragilis accounted for 46.8% of anaerobic bacteria isolated from clinical samples.

The MIC50 and MIC90 values for ampicillin/sulbactam, piperacillin/tazobactam, metronidazole and clindamycin in clinical isolates were at least twice higher than colorectal isolates. One possible reason for this might be the use of antibiotics in these patients.

Although carbapenems have been considered as highly effective antibiotics in the prevention of anaerobic infections, bacterial resistance to these antibiotics has increased [8, 12, 16, 28]. In this study, 1.3% of isolates (n = 1) were resistant to imipenem and 1.3% of isolates (n = 1) were resistant to meropenem. These isolates were collected from the GIT of healthy individuals which could be considered as a serious risk for public health. The emergence of carbapenem resistance has also been reported in different studies. For instance, meropenem resistance was found to be 0.5% in the United States and 2% in Europe [8, 13, 29]. In a study conducted by Kohsari et al. in Iran, the resistance of B. fragilis to meropenem was 13.9% [30]. Discrepancies observed in different studies regarding antibiotic resistance profile of B. fragilis may be due to different reasons including geographical features, population study, and differences in laboratory techniques.

Resistance to carbapenems in B. fragilis is usually caused by the expression of the class B metallo-beta-lactamase encoded by the cfiA gene, located on the chromosome. Accordingly, if an insertion sequence is located in its upstream region, the gene will be expressed and will cause carbapenem resistance [4, 31]. In a study conducted by Sóki et al. 11 out of 15 cfiA positive B. fragilis isolates were resistant to imipenem [32]. In the present study, 18.1 and 12.5% of the clinical and GIT samples had the cfiA gene, respectively. Moreover, the imipenem-resistant isolates had the cfiA gene and the IS1186 insertion sequence in the upstream region of the gene whereas the meropenem-resistant strain had this gene but lacked the IS1186 insertion sequence. The resistance was possibly due to expression of the silent carbapenemase gene [33], the presence of other insertion sequences in the upstream region of this gene (IS1187, IS1188, IS942) [29], or other resistance mechanisms such as membrane permeability or penicillin-binding protein (PBP) affinity [34]. In addition, some isolates had the cfiA gene but were phenotypically sensitive to carbapenem which demonstrate the antibiotic resistance gene may not be expressed. In a study performed by Rashidian et al. in Iran, 31.5 and 20% in B. fragilis group isolate from the patients and control groups harbored cfiA gene, respectively [35].

Penicillins and second-generation cephalosporin resistance have also been observed in B. fragilis.

The most important mechanisms contributing to this resistance is the expression of beta-lactamases which are encoded by the cepA gene (resistance to penicillin and cephalosporins other than cefoxitin) and cfxA gene (resistance to cefoxitin) [36, 37]. In this study, all the isolates (100%) were resistant to penicillin, of which 73.1% had the cepA gene. There was also meaningful difference in penicillin MIC value of isolates with cepA gene compared to isolates without cepA gene indicating the importance of this gene in resistance to penicillin. In addition, 45.5 and 35.7% of the clinical and colorectal isolates were respectively resistant to cefoxitin, and 22.7 and 26.8 % of these isolates had the cfxA gene, respectively. The presence of the cfxA gene was significantly higher in cefoxitin-resistant isolates compare to cefoxitin- susceptible isolates, which was also statistically significant.

The rate of B. fragilis resistance to cefoxitin in recent years has been 6.8–33.3% in Europe, 12.6% in Canada, and 23% in Brazil [8, 38, 39]. In a study conducted by Kangaba et al. in Turkey, 28% of B. fragilis isolates and 32% of isolates from the GIT had been found to be resistant to cefoxitin. In this study, resistance to ampicillin/sulbactam and piperacillin/tazobactam were 6.4 and 2.6%, respectively [6]. In another investigation, 5.4% of B. fragilis isolates were resistant to piperacillin/tazobactam which was relatively consistent with the findings reported by Maraki et al. (5.%) and Yunoki et al. studies (2.8%) [16, 40].

The ermB and mefA genes were also involved in the development of macrolide resistance in B. fragilis [41]. The prevalence of clindamycin resistance had been further reported by 54.5% in clinical isolates and 42.9% in the colorectal isolates which were mainly associated with the presence of the ermF gene [37]. Clindamycin resistance among B. fragilis have been reported in several countries [10, 42,43,44].

In the present study, all clindamycin-resistant isolates had the ermF genes. In addition, five isolates had the mefA gene and three of which were clindamycin-resistant strains. The presence of the ermF gene also was higher in clindamycin-resistant isolates than clindamycin susceptible-isolates respectively, which was statistically significant. None of the isolates in this study had ermB gene.

The presence of tetQ gene associated with tetracycline resistance has been further reported in clinical isolates [40, 45]. In the present study, 81.8 and 71.4 % of the clinical and colorectal isolates had tetracycline resistance, and 90.9 and 85.7% of these isolates had the tetQ genes, respectively.

In a study conducted by Narimani et al. 86% of the colorectal isolates were resistant to tetracycline, and the tetQ gene was found in 85% of the isolates [45]. In the investigation by Kangaba et al. study, 72% of clinical isolates and 92% of colorectal isolates were resistant to tetracycline, 64 and 92% of them had the tetQ gene, respectively [6].

The metronidazole resistance rate was found to be 0–3% in different parts of the world [6, 8, 35, 46]. In addition, Different rates of resistance to metronidazole were reported in different part of Iran. Both in our study and in studies by Rashidan et al., all evaluated strains were susceptible to metronidazole and none of the strains contained nim genes [35]. In a study conducted by Akhi et al. in west of Iran, 8 (32%) out of 26 B.fragilis group isolated from Surgical site infection were resistant to metronidazole [47]. In another study performed by Kouhsari et al. in center of Iran, 6 (1.2%) out of 475 B.fragilis group isolated from Surgical site infection were resistant to metronidazole [30]. This difference in results, may cause from variation in antibiotic usage history of patients, geographical region, and sample size. However, future studies are needed to confirm these results in a higher sample collection from different provinces of Iran.

Based on previous studies, the prevalence of the bft gene was reported to be 6.2–20% in the colorectal isolates [34, 48,49,50,51] and 18.5–38.2% in clinical isolates [51,52,53] which was consistent with the findings in the present study.

Although phenotypic findings indicated resistance to some antibiotics in this study, the PCR findings did not confirm the presence of corresponding resistance genes in the isolates. This fact may suggest the role of other resistance mechanisms such as efflux pumps, changes in the cell wall structure, and catalytic enzymes in B. fragilis isolates [37, 54] that need further investigation.

Conclusions

In our study, metronidazole was only the most in vitro active agent against all of B. fragilis isolates and should be considered as a first-line antibiotic for the empirical treatment of B. fragilis infection. It was concluded that continuous monitoring of antibiotic resistance patterns of B. fragilis in different geographical areas was crucial to provide a suitable treatment profile and to prevent infection more accurately. In addition, with regard to the presence of antibiotic-resistant genes and the high risk of antibiotic-resistant strains in the GIT of healthy people, proper prescription of antibiotics and avoidance of its arbitrary use can help prevent infection and transmission of resistant isolates.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- B. fragilis :

-

Bacteroides fragilis

- GIT:

-

Gastrointestinal tract

- ETBF:

-

Enterotoxigenic B. fragilis

- BFT:

-

B. fragilis toxin

- IBS:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- MIC:

-

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- CFU:

-

Colony-forming unit

- BBE:

-

Bacteroides Bile Esculin Agar

- BBA:

-

Brucella Blood Agar

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

References

Wexler HM. Bacteroides: the Good, the Bad, and the Nitty-Gritty. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00008-07.

Yamamoto T, Ugai H, Nakayama-Imaohji H, Tada A, Elahi M, Houchi H, et al. Characterization of a recombinant Bacteroides fragilis sialidase expressed in Escherichia coli. Anaerobe. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.02.003.

Jeverica S, Sóki J, Premru MM, Nagy E, Papst L. High prevalence of division II (cfiA positive) isolates among blood stream Bacteroides fragilis in Slovenia as determined by MALDI-TOF MS. Anaerobe. 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.01.011.

Yekani M, Baghi HB, Naghili B, Vahed SZ, Sóki J, Memar MY. To resist and persist: Important factors in the pathogenesis of Bacteroides fragilis. Microb Pathog. 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104506.

Buckwold SL, Shoemaker NB, Sears CL, Franco AA. Identification and characterization of conjugative transposons CTn86 and CTn9343 in Bacteroides fragilis strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01669-06.

Kangaba AA, Saglam FY, Tokman HB, Torun M, Torun MM. The prevalence of enterotoxin and antibiotic resistance genes in clinical and intestinal Bacteroides fragilis group isolates in Turkey. Anaerobe. 2015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.07.008.

Urbán E, Horváth Z, Sóki J, Lázár G. First Hungarian case of an infection caused by multidrug-resistant Bacteroides fragilis strain. Anaerobe. 2015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.09.019.

Sóki J, Wybo I, Hajdú E, Toprak NU, Jeverica S, Stingu CS, et al. A Europe-wide assessment of antibiotic resistance rates in Bacteroides and Parabacteroides isolates from intestinal microbiota of healthy subjects. Anaerobe. 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2020.102182.

Salyers AA, Gupta A, Wang Y. Human intestinal bacteria as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes. Trends Microbiol. 2004. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2004.07.004.

Nagy E, Urbán E, Nord CE. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Bacteroides fragilis group isolates in Europe: 20 years of experience. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03256.x.

Fille M, Mango M, Lechner M, Schaumann R. Bacteroides fragilis group: trends in resistance. Curr Microbiol. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-005-0249-x.

Liu CY, Huang YT, Liao CH, Yen LC, Lin HY, Hsueh PR. Increasing trends in antimicrobial resistance among clinically important anaerobes and Bacteroides fragilis isolates causing nosocomial infections: emerging resistance to carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00355-08.

Snydman DR, Jacobus NV, McDermott LA, Ruthazer R, Golan Y, Goldstein EJ, et al. National survey on the susceptibility of Bacteroides fragilis group: report and analysis of trends in the United States from 1997 to 2004. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01435-06.

Goldstein EJC, Citron DM, Tyrrell KL. In vitro activity of eravacycline and comparator antimicrobials against 143 recent strains of Bacteroides and Parabacteroides species. Anaerobe. 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.06.016.

Treviño M, Areses P, Dolores Peñalver M, Cortizo S, Pardo F, Luisa Pérez del Molino M, et al. Susceptibility trends of Bacteroides fragilis group and characterisation of carbapenemase-producing strains by automated REP-PCR and MALDI TOF. Anaerobe. 2012. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.022.

Maraki S, Mavromanolaki VE, Stafylaki D, Kasimati A. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in recent clinical isolates of Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria in a Greek University Hospital. Anaerobe. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2020.102173.

Wang Y, Han Y, Shen H, Lv Y, Zheng W, Wang J. Higher prevalence of multi-antimicrobial resistant Bacteroides spp. strains isolated at a tertiary teaching hospital in China. Infect Drug Resist. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s246318.

Sárvári KP, Sóki J, Kristóf K, Juhász E, Miszti C, Melegh SZ, et al. Molecular characterisation of multidrug-resistant Bacteroides isolates from Hungarian clinical samples. J Global Antimicrob Resist. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2017.10.020.

Cordovana M, Kostrzewa M, Sóki J, Witt E, Ambretti S, Pranada AB. Bacteroides fragilis: A whole MALDI-based workflow from identification to confirmation of carbapenemase production for routine laboratories. Anaerobe. 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.04.004.

Suleiman WB. In vitro estimation of superfluid critical extracts of some plants for their antimicrobial potential, phytochemistry, and GC–MS analyses. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-020-00371-1.

Tille P. Bailey & Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology. Mosby:14th Edition, 2016; Sect. 13.

Fathi P, Wu S. Isolation, detection, and characterization of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis in clinical samples. Open Microbiol J. 2016. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874285801610010057.

Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Miyamoto Y, Takada T, Matsumoto K, et al. Development of 16S rRNA-gene-targeted group-specific primers for the detection and identification of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.68.11.5445-5451.2002.

Tong J, Liu C, Summanen P, Xu H, Finegold SM. Application of quantitative real-time PCR for rapid identification of Bacteroides fragilis group and related organisms in human wound samples. Anaerobe. 2011. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.03.004.

Performance Standards for. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, M100: CLSI, Clinical Laboratory Standards, 30 edition, 2020.

Tran CM, Tanaka K, Watanabe K. PCR-based detection of resistance genes in anaerobic bacteria isolated from intra-abdominal infections. J Infect Chemother. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10156-012-0532-2.

Hecht AL, Casterline BW, Earley ZM, Goo YA, Goodlett DR, Bubeck Wardenburg J. Strain competition restricts colonization of an enteric pathogen and prevents colitis. EMBO Rep. 2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201642282.

Fernández-Canigia L, Litterio M, Legaria MC, Castello L, Predari SC, Di Martino A, et al. First national survey of antibiotic susceptibility of the Bacteroides fragilis group: emerging resistance to carbapenems in Argentina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.05622-11.

Sóki J, Edwards R, Hedberg M, Fang H, Nagy E, Nord CE. Examination of cfiA-mediated carbapenem resistance in Bacteroides fragilis strains from a European antibiotic susceptibility survey. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.07.021.

Kouhsari E, Mohammadzadeh N, Kashanizadeh MG, Saghafi MM, Hallajzadeh M, Fattahi A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance, prevalence of resistance genes, and molecular characterization in intestinal Bacteroides fragilis group isolates. APMIS. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/apm.12943.

Ferløv-Schwensen SA, Sydenham TV, Hansen KCM, Hoegh SV, Justesen US. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and the cfiA resistance gene in Danish Bacteroides fragilis group isolates since 1973. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.05.007.

Sóki J, Fodor E, Hecht DW, Edwards R, Rotimi VO, Kerekes I, et al. Molecular characterization of imipenem-resistant, cfiA-positive Bacteroides fragilis isolates from the USA, Hungary and Kuwait. J Med Microbiol. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.05452-0.

Podglajen I, Breuil J, Bordon F, Gutmann L, Collatz E. A silent carbapenemase gene in strains of Bacteroides fragilis can be expressed after a one-step mutation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1097(92)90557-5.

Kierzkowska M, Majewska A, Szymanek-Majchrzak K, Sawicka-Grzelak A, Mlynarczyk A, Mlynarczyk G. The presence of antibiotic resistance genes and bft genes as well as antibiotic susceptibility testing of Bacteroides fragilis strains isolated from inpatients of the Infant Jesus Teaching Hospital, Warsaw during 2007–2012. Anaerobe. 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.03.003.

Rashidan M, Azimirad M, Alebouyeh M, Ghobakhlou M, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Zali MR. Detection of B. fragilis group and diversity of bft enterotoxin and antibiotic resistance markers cepA, cfiA and nim among intestinal Bacteroides fragilis strains in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Anaerobe. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.02.005.

Rogers MB, Parker AC, Smith CJ. Cloning and characterization of the endogenous cephalosporinase gene, cepA, from Bacteroides fragilis reveals a new subgroup of Ambler class A beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.37.11.2391.

Eitel Z, Sóki J, Urbán E, Nagy E. The prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in Bacteroides fragilis group strains isolated in different European countries. Anaerobe. 2013. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.03.001.

Marchand-Austin A, Rawte P, Toye B, Jamieson FB, Farrell DJ, Patel SN. Antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates of anaerobic bacteria in Ontario, 2010–2011. Anaerobe. 2014. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.05.015.

Nakano V, Avila-Campos MJ. Virulence markers and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria of the Bacteroides fragilis group isolated from stool of children with diarrhea in São Paulo, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/s0074-02762004000300012.

Yunoki T, Matsumura Y, Yamamoto M, Tanaka M, Hamano K, Nakano S, et al. Genetic identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of clinically isolated anaerobic bacteria: a prospective multicenter surveillance study in Japan. Anaerobe. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.09.003.

Kierzkowska M, Majewska A, Szymanek-Majchrzak K, Sawicka-Grzelak A, Mlynarczyk A, Mlynarczyk G. In vitro effect of clindamycin against Bacteroides and Parabacteroides isolates in Poland. J Global Antimicrob Resist. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2017.11.001.

Veloo ACM, van Winkelhoff AJ. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of anaerobic pathogens in The Netherlands. Anaerobe. 2015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.08.011.

Sárvári KP, Sóki J, Kristóf K, Juhász E, Miszti C, Latkóczy K, et al. A multicentre survey of the antibiotic susceptibility of clinical Bacteroides species from Hungary. Infect Dis (London, England). 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2017.1418530.

Boyanova L, Kolarov R, Mitov I. Recent evolution of antibiotic resistance in the anaerobes as compared to previous decades. Anaerobe. 2015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.05.004.

Narimani T, Douraghi M, Owlia P, Rastegar A, Esghaei M, Nasr B, et al. Heterogeneity in resistant fecal Bacteroides fragilis group collected from healthy people. Microb Pathog. 2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.017.

Dumont Y, Bonzon L, Michon AL, Carriere C, Didelot MN, Laurens C, et al. Epidemiology and microbiological features of anaerobic bacteremia in two French University hospitals. Anaerobe. 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2020.102207.

Akhi MT, Ghotaslou R, Beheshtirouy S, Asgharzadeh M, Pirzadeh T, Asghari B, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria isolated from surgical site infection of hospitalized patients. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2015;8(7):e20309. https://doi.org/10.5812/jjm.20309v2.

Ulger Toprak N, Rajendram D, Yagci A, Gharbia S, Shah HN, Gulluoglu BM, et al. The distribution of the bft alleles among enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis strains from stool specimens and extraintestinal sites. Anaerobe. 2006. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2005.11.001.

Łuczak M, Obuch-Woszczatyński P, Pituch H, Leszczyński P, Martirosian G, Patrick S, et al. Search for enterotoxin gene in Bacteroides fragilis strains isolated from clinical specimens in Poland, Great Britain, The Netherlands and France. Med Sci Monitor. 2001;7(2):222–5.

Jasemi S, Emaneini M, Fazeli MS, Ahmadinejad Z, Nomanpour B, Sadeghpour Heravi F, et al. Toxigenic and non-toxigenic patterns I, II and III and biofilm-forming ability in Bacteroides fragilis strains isolated from patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Gut Pathog. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-020-00366-5.

Chung GT, Franco AA, Wu S, Rhie GE, Cheng R, Oh HB, et al. Identification of a third metalloprotease toxin gene in extraintestinal isolates of Bacteroides fragilis. Infect Immun. 1999. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.67.9.4945-4949.1999.

Szöke I, Dósa E, Nagy E. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis in Hungary. Anaerobe. 1997. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/anae.1997.0078.

Mundy LM, Sears CL. Detection of toxin production by Bacteroides fragilis: assay development and screening of extraintestinal clinical isolates. Clin Infect Dis. 1996. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/23.2.269.

Sóki J, Eitel Z, Urbán E, Nagy E. Molecular analysis of the carbapenem and metronidazole resistance mechanisms of Bacteroides strains reported in a Europe-wide antibiotic resistance survey. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.10.001.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the personnel of the infectious unit of Tehran’s Imam Khomeini Hospital for them assistance in this project.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by Elite Researcher Grant Committee under award number [NO. 97132] from the National Institutes for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Tehran, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJ carried out all laboratory experiment, collected data and drafted the manuscript. ZA and MSF are infectious disease specialists and gastroenterologists who provided the specimens from all cases. LS and FH participated in the design of the study. MF and ME supervised all parts of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Ethics Approval Code: 9421133003.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained in all cases.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jasemi, S., Emaneini, M., Ahmadinejad, Z. et al. Antibiotic resistance pattern of Bacteroides fragilis isolated from clinical and colorectal specimens. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 20, 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-021-00435-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-021-00435-w