Abstract

Background

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains are prevalent in healthcare services. Medical students are at risk for MRSA carriage, subsequent infection and potential transmission of nosocomial infection.Few studies have examined MRSA carriage among medical students.

Methods

In this prospective cohort study, between July 2016 and June 2017, two nasal swab samples were taken per student 4 weeks apart during their pediatric internship. MRSA typing was performed by staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types, Panton Valentine leukocidin (PVL) encoding genes.

Results

A total of 239 sixth year medical students, 164 (68.6%) male (M/F:2.1),with median age 25 years (min–max; 23–65 years) were included in this prospective cohort study. Among 239 students, 17 students (7.1%) were found to be colonized with methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) at the beginning of pediatric internship. After 4 weeks, at the end of pediatric internship totally 52 students were found to be S. aureus colonized (21.8%). Three of 52 S. aureus isolates were MRSA (1.3%) and the rest was MSSA (20.5%), all were PVL gen negative. Two of three MRSA isolates were characterized as SCCmec type IV, one isolate was untypeable SCCmec. Nasal carriage of S. aureus increased from 7.1% to 21.5% (p < 0.001). Nasal S. aures colonization ratio was higher in students working in pediatric infectious disease service (p = 0.046). Smoking was found to be associated with a 2.37-fold [95% CI (1.12–5.00); p = 0.023] and number of patients in pediatric services was 2.66-fold [95% CI (1.13–6.27); p = 0.024] increase the risk of nasal S. aureus colonization. Gender was not found to increase risk of MRSA carriage.

Conclusion

MSSA nasal carriage increased at the end of pediatric internship and significantly high in students working in pediatric infectious diseases services. Smoking and high number of patients in pediatric services significantly increase S.aureus colonization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (S.aureus) remains a common cause of infection in the community for centuries. The spectrum of the diseases caused S. aureus varies from mild skin infection to endocarditis or life-threatening septicemia. In the last few decades, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has become an increasingly important cause of healthcare-associated infections.

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus widely known as the superbug, was first reported in the early 1960s. Within years, it rapidly spread in the community and health-care settings. At present, MRSA is endemic in health-care settings globally, which results in a heavy disease burden. MRSA infections were associated mostly with hospitals and infected patients who had contact with the health-care system, hence the name health-care associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) [1,2,3,4]. These strains were typically resistant to multiple antimicrobials and carried large staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) elements, mostly types I–III. Cases of MRSA infections have been increasingly reported during the last decade in healthy individuals of the general population with no risk factors for these community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) infection. Community-associated MRSA strains were not multidrug-resistant, carried small SCCmec elements, mostly types IV and V, and also carried the genes encoding the Panton Valentine leukocidin (PVL), a pore-forming toxin [5,6,7].

Health care workers (HCWs) play a significant role in the epidemiology of MRSA infections.HCWs act as vectors for transmission of MRSA as they work at the interface between hospital and the community. Transmission of MRSA in the healthcare environment is usually by contact between patients through hands, clothes or equipment of HCWs.

Dynamics and prevalence of MRSA colonization are affected by several factors such as type of hospital department, MRSA prevalence among patients, and inadequate compliance with infection control measures; these differ depending on geographical locations [8,9,10].

Medical students represent an important portion of the health-care personnel, and they are in frequent contact with susceptible patients; thus, they are at risk of being colonized with S. aureus, and of spreading them to susceptible patients. The aim of this study was to examine Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage, SCCmec and PVL molecular typing and risk factors of medical students during their pediatric services practices.

Material and methods

The study was performed at Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, between July 2016 and June 2017 in sixth year medical students working in pediatric services; neonatal intensive care unit, neonatal surgery service, intensive care unit, infant service, young child service, adolescent service, hematology service, infectious disease service during 4 weeks internship.

Students who agreed to participate were asked to sign an informed consent and complete a written questionnaire on demographics and medical history. Variables included in the questionnaire were age, gender, housemate, living with children and/or health-care personnel, history of infections, allergies, chronic underlying diseases, smoking habits, antibiotic usage in the previous three months, surgeries and hospitalizations in the previous 1 year. Exclusion criterias were usage of intranasal mupirocin, oral beta-lactam antibiotic and/or clindamycin in the past 3 month. Also students working with other health care workers were excluded.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hacettepe University, Faculty of Medicine.

Isolation, growth and identification of bacteria

Samples were collected from both anterior nares (vestibulum nasi) using nasal swabs with a standard rotating technique from sixth year medical students, four weeks apart; at the beginning and at the end of abovementioned pediatric services. Swabs were taken during the admission process, were transported in Stuart’s medium, stored at 4 °C and plated within a few hours on Columbia and Mannitol Salt Agar plates (all Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Colony characteristicson the culture plates and Gram-staining were usedto further confirm the identity of S. aureus. Salt tolerance and mannitol fermentation properties of S. aureus result in the typical yellow colonies due to a changein the pH. Gram staining helped to ascertain thatthere were no other airborne contaminants by con-firming the characteristic morphology of S. aureus. Yellow colonies were selected and confirmed to be S. aureus following catalase, coagulase, and DNAse tests and were finally confirmed by PCR using specific primers as shown below. ATCC 25923 standart strain was used for culture and biochemical reactions, S. aureus ATCC 29213 standart strain was used for antimicrobial susceptibility tests. S. aureus ATCC 49775 standart strain was used for PVL gen PCR analysis. Standart strains for SCCmec PCR analysis were as follows respectively; S.aureus COL for SCCmecI, S.aureus BK2464 for SCCmec II, S.aureus ANS46 for SCCmec III, S.aureus HDE288 for SCCmec IV.

Tests for methicillin resistance were performed using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method, using cefoxitin (30 μg) disc on Mueller–Hinton agar with 24-h. Results were interpreted according to the criteria of CLSI (2017). Zone of inhibition of cefoxitin disc ≥ 22 mm was accepted as methicillin-sensitive S. aureus.

The mecA gene, SCCmec types and PVL genes were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). MRSA isolates were subjected to SCCmec typing as described by Oliveira et al. [11], which is based on a set of multiplex PCR reactions with 14 primers. SCCmec types I–IV were assigned according to the combination of the cassette chromosome recombinase (ccr) type and mec class. MRSA isolates that could not be assigned to any expected type were defined as non-typable (NT).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS package program for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Values for numerical variables were provided as mean ± standard deviation or median (minimum–maximum) depending on normality of distribution. Categorical variables were provided as absolute values or percentages, the comparisons of which were made using the chi-square test. Two-way comparisons for numerical variables were made using the Mann–Whitney U test, whereas the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparison involving more than two groups. Factors associated with an increased nasal S. aureus colonization were identified using logistic regression analysis. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

A total of 239 sixth year medical students, of whom 164 (68.6%) male, were included in this prospective cohort study. Median age of the students was 25 years (min–max; 23–65 years). Eight (3.3%) of the students were married, 116 (48.5%) students were living friends. Twenty-two (9.2%) students were living with at least one child. Underlying diseases of students that may increase risk of S. aureus colonization were; allergic rhinitis (n = 30) and diabetes mellitus (n = 1). Seventy-one students (29.7%) were occasionally smoker, 20 students (8.4%) were frequent smoker. None of the students had history of hospitalization or surgery history at the previous one year (Table 1).

At the beginning of pediatric internship, 44 students (18.4%) were working in child intensive care unit, 42 students (17.6%) were working in infant infectious diseases service, 37 students (15.5%) were working in pediatric infectious diseases service, 33 students (13.8%) were working in neonatal surgery service, 32 students (13.4%) were working in hematology service, 22 students (9.2%) were working in young child service, 22 students (12.1%) were working in adolescent service. S. aureus was cultured from 17 of 239 (7.1%) nasal cultures taken at the beginning of pediatric internship, all of the 17 (7.1%) isolates were methicillin sensitive, PVL gen negative. Sixteen of 17 MSSA cultured students (94.1%) were not married, two students (11.8%) were living alone, six students (35.3%) were living with family, nine students (52.9%) were living with friends, eleven students (64.7%) were on medical education for more than 6 years, six students (35.3%) were frequent-smokers, two students (11.8%) stated using steroid in the past 3 months, three students (17.6%) stated using antibiotics in the past 3 months, eight students (47%) explained of having respiratory tract infections in the past 3 months. None had history of hospitalization in the past 3 months.

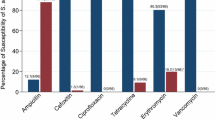

At the end of pediatric intership, S. aureus was isolated in 52 of 239 (21.8%) nasal sample cultures; 49 (20.5%) MSSA, 3 (1.3%) MRSA (Table 2). Two of three MRSA (66.7%) cultured nasal samples were taken from students working in infant infectious diseases service, one was from student (33.3%) working in pediatric infectious diseases service.None of the 52 S. aureus isolates were PVL gen positive. Two of three MRSA isolates were SCCmec tip IV (66.6%), one MRSA isolate was non-typeable. One of 49 MSSA cultured students was married (2%), 31 students (63.3%) were living with friends, eleven students (22.4%) were living with family, seven students (14.3%) were living alone, two students (4.1%) were living with a child at home. Twenty students (40.8%) were on medical education for more than six years, 26 students (53.1%) were frequent-smokers, three students (6.1%) stated using steroid in the past three months, eight students (16.3%) declared using antibiotic in the past three months, eighteen students (36.7%) had history of respiratory tract infection in the past three months. Two of three MRSA isolated students (66.7%) stated living with health-care worker at home, were on medical education for more than six years. One of three MRSA isolated student (33.3%) stated frequent smoking, upper respiratory tract infection history in the past three months. None of three MRSA isolated students were married nor had history of using antibiotics or steroid in the past three months.

Increase in nasal colonization of S. aureus in comparison with first and second samples was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Sixteen of 17 MSSA isolates cultured at the first samples were found MSSA again at the second samples, but 1 MSSA isolate cultured at the first samples was found as MRSA at the second sample (Fig. 1). Nasal S. aureus colonization according to pediatric services at the beginning and at the end of the internship was depicted in Fig. 2. Nasal S. aureus colonization at the end of infectious disease service internship was statistically significantly increased (p = 0.046).

It was found that living alone or with family, friends did not increase the risk of nasal S. aureus colonization in students (p = 0.55). Living with a child (p = 0.177) and/or history of using antibiotic (p = 0.457) and/or steroid (p = 0.731) in the past three months, history of upper respiratory tract or skin infections in the past three months did not increase the risk of nasal S. aureus colonization (p = 0.138).

Smoking was found to be associated with a 2.37-fold [95% CI (1.12–5.00); p = 0.023] and number of patients in pediatric services was 2.66-fold [95% CI (1.13–6.27); p = 0.024] increase the risk of nasal S. aureus colonization (Table 3).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report nasal S. aureus and MRSA carriage rates, molecular characteristics in medical students, according to services at the beginning and end of their pediatric practices. In addition, this is the first study from Turkey in which PVL and SCCmec gens were studied from S. aureus nasal samples of medical students. Among 239 students, 17 students (7.1%) were found to be colonized with MSSA at the beginning of pediatric internship. After four weeks, at the end of pediatric internship totally 52 (21.5%) students were found to be S. aureus colonized. Three of 52 (1.3%) S. aureus isolates were MRSA and the rest was MSSA (20.5%). Two of three MRSA isolates were characterized as SCCmec type IV, one isolate was untypeable SCCmec. Nasal carriage of S. aureus increased statistically significantly from 7.1% to 21.5%. Nasal S. aures colonization ratio was higher in students working in pediatric infectious diseases service. Smoking and number of patients in pediatric services was found to increase risk of nasal S. aureus colonization.

In a study conducted in Poland, asymptomatic colonization with S. aureus strains was found in 245/955 (25.7%) students, in particular years in the range of 21.7–29.9%, similar to our results but molecular analysis was not done in aforementioned study [12]. In a study from Israel, among 58 students, S. aureus carriage rates increased from 33 to 38% to 41% at baseline (preclinical studies), 13 and 19 months (clinical studies), respectively (p = 0.07). MSSA carriage increased in the clinical studies period (22 to 41%, p = 0.01), similar to our results. Overall, seven students (12%) carried 13 MRSA isolates. MRSA isolates were PVL negative and were characterized as SCCmecII-t002, SCCmecIV-t032, or t12435 with untypable SCCmec. In our results, MRSA carriage was not as high as this study also SCCmecIV was the dominant type [13]. In another study from China conducted in interns, the prevalence of S. aureus among staphylococcal specimens was 23.1%, similar to our results, and in that study the MRSA prevalence was reported as 9.4% with SCCmec type IV dominancy, PVL gen positivity in 10 (45.4%) MRSA isolates [14].

In a study conducted from Turkey in 269 health care workers, the prevalence of S. aureus carriage was 20.1%, only one MRSA (0.37%), similar to our results. In that study, S. aureus carriage was found to be significantly lower in the smoker group (p = 0.015) in opposite to our results [15]. In another study from Turkey, nasal samples from elementary school children were taken and all MRSA isolates by harbored the SCCmec type IV element, but not the PVL gene like in our results [16]. In our study, nasal S. aureus colonization of medical students was 7.1% at the beginning of pediatric internship. In second samples, 3 MRSA (1.3%) and 49 MSSA (20.5%) totally 52 students (21.8%) were colonized with S. aureus isolates. Two of 3 MRSA isolates were harboring SCCmec type IV gene. None of the S. aureus isolates were harboring PVL gene. SCCmec type IV and PVL gens are known to be more common in community-acquired MRSA infections. Our results support possibility of SCCmec type IV positivity in hospital-acquired MRSA isolates. In a study conducted in hospitalized adult patients between 2004 and 2005 in Hacettepe University, 110 MRSA isolates were found to be mecA gen positive, 68 MRSA isolates were harboring (61.8%) SCCmec type III, 38 isolates (34.5%) were harboring SCCmec IIIB and 3 isolates (2.7%) were harboring SCCmec tip IV [17]. In another study conducted in our center in hospitalized pediatric patients, 2 of 30 MRSA (6.7%) isolates was were found to be positive for SCCmec type III and 16 MRSA isolates (53.3%) were found to be positive for SCCmec type IV, indicating SCCmec type IV dominancy in our pediatric center [18].

In students working in infant infectious diseases and pediatric infectious diseases service nasal S. aureus carriage and risk of methicillin resistance was statistically significantly increased. Nasal S. aureus colonization of students was more prevalent in services where the number of hospitalized patients increased. Marital status, living with children or health-care worker or family were not found to increase risk of nasal S. aureus colonization. In a study published at Lancet in 2014, nasal S. aureus carriage 34.6% in 347 preclinical and clinical medical students, MRSA colonization was 1.9%. Nasal S.aureus carriage rate was more than what we found, but in aforementioned study there was no discrimination according to pediatric services as we did [19]. In another study published in 2018, 200 medical students were included, MRSA colonization was 2%, SCCmec type I and III were more prevalent [20]. Collazos et al. found that, nasal S. aureus colonization rate was 23.6% in 216 medical students and MRSA colonization was 14.3%, compared to our study it was more prevalent [21].

In Turkey MRSA had been noticed as an important nosocomial infection reason since 1980s. Medical students constitute a commonly forgotten health-care workers who are often not as well informed as other health-care personnel about standard infection control measures. As a result of our study, students that had worked in infectious diseases services where patients were hospitalized due to pneumonia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, bacteremia, cellulitis, meningitis were more commonly colonized with S. aureus, particularly MRSA at the end of pediatric internship. This finding highlighted us about increasing infectious control precautions in these services. It may be logical to check health-care workers for nasal S. aureus colonization periodically in services where high risk patients for invasive S. aureus infections are hospitalized.

References

Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, Nouwen JL. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:751–62.

Lee AS, de Lencastre H, Garau J, Kluytmans J, Malhotra-Kumar S, Peschel A, Harbarth S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;31(4):18033.

Kluytmans JA, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505–20.

Gupta K, Martinello RA, Young M, Strymish J, Cho K, Lawler E. MRSA nasal carriage patterns and the subsequent risk of conversion between patterns, infection, and death. PLoS ONE. 2003;8(1):53674.

Shore AC, Coleman DC. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec: recent advances and new insights. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303(6–7):350–9.

Yamaguchi T, Ono D, Sato A. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) analysis of MRSA. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2069:59–78.

Lakhundi S, Zhang K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31(4):e00020-e118.

Tacconelli E, Johnson AP. National guidelines for decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriers: the implications of recent experience in the Netherlands. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2195–8.

Humphreys H. Can we do better in controlling and preventing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the intensive care unit (ICU)? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:409–13.

Bode LG, Kluytmans JA, Wertheim HF, Bogaers D, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Roosendaal R, Troelstra A, et al. Preventing surgical-site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:9–17.

Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2155–61.

Szymanek-Majchrzak K, Kosiński J, Żak K, Sułek K, Młynarczyk A, Młynarczyk G. Prevalence of methicillin resistant and mupirocin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains among medical students of Medical University in Warsaw. Przegl Epidemiol. 2019;73(1):39–48.

Orlin I, Rokney A, Onn A, Glikman D, Peretz A. Hospital clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus are carried by medical students even before healthcare exposure. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:15.

Ma XX, Sun DD, Wang S, et al. Nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among preclinical medical students: epidemiologic and molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant S. aureus clones. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70(1):22–30.

Genc O, Arikan I. The relationship between hand hygiene practices and nasal Staphylococcus aureus carriage in healthcare workers. Med Lav. 2020;111(1):54–62.

Kilic A, Mert G, Senses Z, et al. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal isolates from Turkey. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2008;94(4):615–9.

Akoğlu H, Zarakolu P, Altun B, Ünal S. Epidemiological and molecular characteristics of hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in Hacettepe University Adult Hospital in 2004–2005. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2010;44:343–55.

Arıkan K, Karadag-Oncel E, Aycan AE, Yuksekkaya S, Sancak B, Ceyhan M. Epidemiologic and molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus strains ısolated from hospitalized pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;26:1002–6.

Carmona-Torre F, Torrellas B, Rua M, Yuste JR, Del Pozo JL. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage among medical students. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:477–8.

Suhaili Z, Amira PR, Mat Azis N, Yeo CC, Nordi SA, Abdul Rahim AR, Mazen M, et al. Characterization of resistance to selected antibiotics and Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureusin a healthy student population at a Malaysian University. GERMS. 2018;8(1):21.

Collazos Marín LF, Arciniegas EGE, Vivas MC. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureusısolates that colonize medical students in a hospital of the City of Cali Colombia. Int J Microbiol. 2015;2015:358489.

Prior publications

There are no prior publications or submissions with any overlapping information, including studies and patients.

Funding

This study was supported by Hacettepe University, Scientific Research Department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written by Dr Kamile Arıkan. All authors have made substantive contributions to the manuscript, and all authors endorse the data and conclusions. All the named authors have seen and agreed to the submitted version of paper. Honorarium, grant or other form of payment was not given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arıkan, K., Karadag-Oncel, E., Aycan, E. et al. Molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from nasal samples of sixth year medical students during their pediatric services practices. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 20, 25 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-021-00429-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-021-00429-8