Abstract

Background

Research related to sustainable diets is is highly relevant to provide better understanding of the impact of dietary intake on the health and the environment.

Aim

To assess the association between the adherence to an energy-restricted Mediterranean diet and the amount of CO2 emitted in an older adult population.

Design and population

Using a cross-sectional design, the association between the adherence to an energy-reduced Mediterranean Diet (erMedDiet) score and dietary CO2 emissions in 6646 participants was assessed.

Methods

Food intake and adherence to the erMedDiet was assessed using validated food frequency questionnaire and 17-item Mediterranean questionnaire. Sociodemographic characteristics were documented. Environmental impact was calculated through greenhouse gas emissions estimations, specifically CO2 emissions of each participant diet per day, using a European database. Participants were distributed in quartiles according to their estimated CO2 emissions expressed in kg/day: Q1 (≤2.01 kg CO2), Q2 (2.02-2.34 kg CO2), Q3 (2.35-2.79 kg CO2) and Q4 (≥2.80 kg CO2).

Results

More men than women induced higher dietary levels of CO2 emissions. Participants reporting higher consumption of vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole cereals, preferring white meat, and having less consumption of red meat were mostly emitting less kg of CO2 through diet. Participants with higher adherence to the Mediterranean Diet showed lower odds for dietary CO2 emissions: Q2 (OR 0.87; 95%CI: 0.76-1.00), Q3 (OR 0.69; 95%CI: 0.69-0.79) and Q4 (OR 0.48; 95%CI: 0.42-0.55) vs Q1 (reference).

Conclusions

The Mediterranean diet can be environmentally protective since the higher the adherence to the Mediterranean diet, the lower total dietary CO2 emissions. Mediterranean Diet index may be used as a pollution level index.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite law regulations issued in the last few decades, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have increased, affecting climate change as well as the way of life. Carbon dioxide (CO2) represents one of the main GHG. As such, its reduction is part of the United Nations agenda 2030 which, in general terms, aims to eradicate poverty and promote sustainable and equalitarian development by 2030 following 17 sustainable development goals [1].

Global dietary patterns have changed too, and a new lifestyle characterized as quick and stressful has affected our way of purchasing and eating food, causing a detrimental impact on our health. This new way of living has also changed due to the increasing demand of meat protein, driven by the increasing of annual incomes in the last decades. A demand of empty calories found in products like refined cereals, refined sugars, alcohol, and oils was another of the global changes. Finally, the total per capita caloric demand increased as well [2].

New food habits and dietary changes have affected the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, since food system emissions are around 1/3 of the global GHG emissions, representing 34% of total CO2 equivalents in 2015 [3]. Each increased step in the food chain has an added impact on the degradation of the environment. The production step has a particular impact, and this is the reason why the Eat Lancet Commission established that major changes must be made on both the way we eat and the way we produce our food to stop this detrimental situation [4].

Accordingly, there is a diet-environmental-health trilemma and research on how to be more sustainable and reduce those impacts has been increasing. Sustainable diets are those with low environmental impacts which contribute to food and nutrition security and to a healthy life for present and future generations. These types of diets are protective and respectful of biodiversity and ecosystems, culturally acceptable, accessible, economically fair, and affordable; nutritionally adequate, safe and healthy, while optimizing natural and human resources [5].

The traditional Mediterranean diet is a well-studied model in terms of healthfulness being researched for its protective effects on cardiometabolic risk factors and reducing the incidence on major cardiovascular events in a high-risk population [6]. Nowadays, cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of death in developed countries as well as in Spain [7]. According to the World Heart Federation, tobacco, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, diabetes, physical inactivity, and inadequate diet are the main cardiovascular disease risk factors [8]. Due to its beneficial effects on cardiovascular health, Mediterranean diet is commonly recommended.

The Mediterranean Diet is characterized by a high consumption of fruits and vegetables, unrefined cereals, plant-origin proteins, and healthy fats such as olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish. A low consumption of animal products, mainly red and processed meat, which is one of the main contributors to CO2 emissions, is also one of the key traits of the characteristic points of the Mediterranean diet. Limiting overconsumption and energy intakes to an amount that meets recommendations was proposed as another possible beneficial aspect for reducing the impact on the ecosystems, and this also may help to decrease the obesity epidemic [9].

People following the Mediterranean Diet are already beneficiated for its protective effects on health. It would be interesting to study if people following the Mediterranean Diet are also protecting the environment while reducing CO2 emissions. The present study offers an opportunity to assess the association between the adherence to an energy-restricted Mediterranean diet and the amount of CO2 emitted in an older adult population.

Methodology

Study design

The present research was a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data within an ongoing 8-year multicenter, parallel-group, randomized trial, conducted in 23 Spanish recruiting centers aiming to assess the effect of weight-loss induced by a hypocaloric traditional Mediterranean Diet combined with physical activity promotion and behavioral support on cardiovascular disease and mortality. The study protocol can be found elsewhere [10]. The trial was registered in 2014 at the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial (ISRCT; http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN89898870) with number 89898870.

Participants, recruitment, and ethics

A total of 9677 participants were contacted; 6874 participants met the inclusion criteria including men aged 55-76 and women aged 60-75, with overweight or obese (body mass index between 27 and 40 kg/m2) and meeting at least three criteria for metabolic syndrome according to the Association and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [11]. Finally, 6646 participants were included in the analysis after excluding those with incomplete FFQ data and reporting extreme energy intakes (< 500 or > 3500 kcal/day in women or < 800 or > 4000 kcal/day in men) [12]. A flow-chart of eligible participants was shown in Fig. 1.

Informed written consent was provided by all participants and the study protocol and procedures were approved by ethical committees according to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki by all the 23 participating institutions.

Assessment of dietary intake

Registered dietitians assessed dietary habits, at baseline, through a semi quantitative 143-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [13] which has been previously validated in Spanish population [13,14,15]. For each item, a regular portion size was established, and consumption frequencies were registered according to 9 categories, ranging from “never or almost never” to “≥6 times/day”. Energy and nutrient intakes were calculated as frequency multiplied by nutrient composition of specified portion size for each food item, using a computer program based on available information from Spanish food composition tables [16, 17]. The results were used to determine the specific amount of food (in grams) each participant had eaten per day.

CO2 emitted per kg of food

The amount of CO2 emitted per kg of consumed food per participant and day was calculated using a European database from 2016 that described kg of CO2 emitted per kg of food consumed. This database was based on life cycle assessment (LCA) of recent studies and included agricultural production and processing steps (considering defaults for cooking, storing, and packing and letting transportation out of the calculations) [18]. Kilograms of CO2 emitted per consumed food were calculated by multiplying g of each consumed food reported from the FFQ per kg of CO2 emitted per kg of each food from the database. The sum of all kilograms of CO2 emitted for all the products was done to determine the total emissions a day from diet. Once the CO2 emitted for each participant was known, an adjustment per 1 kg of food consumed was completed. The adjustment was done to consider the energy intake cofounder. Depending on the individual needs, the dietary intake could be higher in terms of quantity meaning higher emissions, even when comparing diets based on the same products. Therefore, an adjustment per 1 kg of food product per person offers a better comparison between the emissions of the participants’ diets and avoids bias for people who could eat higher amounts due to their personal needs.

Assessment of adherence to the erMedDiet

Adherence to energy-reduced Mediterranean diet was assessed using a 17-item Mediterranean Diet validated questionnaire [19].

Other health variables

Information related to sociodemographic characteristics such as sex, age, and scholar level were self-reported. Anthropometric measurements (including weight, height, waist, and hip circumference) were obtained.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software package version 27.0 (SPPS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are shown as mean and standard deviation (SD), except for prevalence data, which was expressed as sample size and percentage. Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post-hoc was used for continuous variables. To assess the linear trend, the median value of each quartile of CO2 emissions was assigned and used as a continuous variable in the logistic regression model. Logistic regression was fitted to assess association between each one of the 17-items of erMedDiet questionnaire and the mean adherence to the Mediterranean Diet (as dependent variables) and quartiles of dietary CO2 emitted (as independent variable) calculating Odds Ratio (OR) value, crude and adjusted (by sex, age, and educational level). Data on the amount of CO2 emissions per participant and day were distributed in quartiles: quartile 1 (Q1); participants with the lowest emissions (≤2.01 kg CO2/day), quartile 2 (Q2); participants with low-moderate emissions (2.02-2.34 kg CO2/day), quartile 3 (Q3); participants with moderate-high emissions (2.35-2.79 kg CO2/day) and quartile 4 (Q4); participants with the highest emissions (≥2.80 kg CO2/day). Q1 was considered as the reference. A linear prediction with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated between quartiles of dietary CO2 and the erMedDiet adherence score.

Results

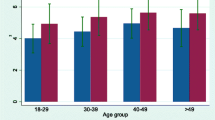

Table 1 shows the association between sex, age, scholar level, and adherence to the erMedDiet according to the kg CO2 emissions per kg of food. More men than women were classified into quartiles 3 (Q3) and 4 (Q4), which shows higher levels of CO2 emissions in men’s diets. Compared to those in the lowest quartile of kg CO2 emissions per kg of food, participants in the top quartile were more likely to be men, younger and with lower education level.

The association between the adherence to the erMedDiet and its components across of quartiles of kg CO2 emissions per kg of food are showed in Table 1. Adherence to the erMedDiet was inversely associated across quartile of kg CO2 emissions per kg of food. A higher number of participants reporting higher adherence to the Mediterranean Diet were found in Q1 and Q2.

Crude and adjusted OR for adherence to Mediterranean Diet is shown in Table 2. Q1 (≤2.01 kg CO2) was the reference, and the adjustment was done by sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, and scholar level). Crude and adjusted OR values on total Mediterranean Diet adherence were lower in both Q3 (OR 0.69 0.60-0.79) and Q4 (0.48 0.42-0.55) than in Q2 (OR 0.87 0.76-1.00), which means that participants high followers of Mediterranean Diet showed lower amount of CO2 emissions.

Figure 2 shows that there was lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet in those participants with higher CO2 emissions.

Discussion

The current study showed that CO2 emissions were inversely associated with the adherence to the Mediterranean Diet. It also opened the idea of using the erMedDiet index as a pollution level index. Studies in younger populations have already shown how a Mediterranean Diet could be proposed as a sustainable dietary model in terms of food production and processing. Better adherence to the Mediterranean Diet has been associated with lower land use, water consumption, energy consumption and GHG emissions [20]. Another study in Italian children compared the CO2 emissions of the Mediterranean Diet between winter and spring; impacts were higher in winter than in spring, and meat products were the major contributors to GHG emissions in both seasons, followed by milk and dairy products [21].

The scope of several studies has compared the Mediterranean Diet with other dietary patterns. A Western Diet (WD), characterized by a high consumption of meat, sweets, and beverages, appears to be the unhealthiest and the most detrimental pattern in terms of the environment, but the most affordable [22]. Compared to a Western Dietary pattern, the Mediterranean Diet in Spain would substantially reduce GHG emissions, land use and energy consumption, and lower extent water consumption [23]. Moreover, GHG emissions were lower for Mediterranean Diet pattern with a consistent emission 14.55% below to an Italian average diet and 6.74% below the Mediterranean Diet [24]. Compared to the DASH or Nordic Diets, higher adherence to the Mediterranean Diet has been associated with lower GHG emissions [25].

Other studies have calculated the environmental impact of different dietary scenarios, mainly based on healthy recommendations or food based dietary guidelines [26,27,28] or trying to represent a specific diet of a country [29, 30]. A reduction in premature mortality and a reduction in GHG emissions were seen in the healthy and sustainable diets [26, 29]. A common factor of those dietary scenarios was the reduction in animal-based products with an increase focus on plant-based foods [25,26,27,28,29]. This is relevant to the present analyses, as the Mediterranean Diet is a plant-forward dietary pattern because it emphasizes consumption of fruits and vegetables, healthy fats, whole cereals, as well as a preference for fish and white meat, with an overall reduction in red and processed meat [31].

Several studies have evaluated the environmental impact of a diet related to a specific country or a region, for instance, Switzerland [32], China [33,34,35], France, United Kingdom, Finland, and Sweden [36], Italy [36, 37], Netherlands [38], Uganda [39], India [40], Germany [41] and the Atlantic region [42, 43]. In European countries, a transition towards a healthier diet following the recommended guidelines and achieving nutritional adequacy has resulted to be the most sustainable option. Reductions in consumption of animal-based products are needed with differences according to country, sex, and food [32, 36,37,38, 41,42,43]. Major decreases in consumption of meat, snacks, and butter are needed in the Netherlands in conjunction with an increase in consumption of legumes, fish, nuts, and vegetables [38]. The Atlantic region diet has high GHG emissions, since it is based in livestock products and shellfish; however, it appears to have a high nutritional score mainly because of a low intake of sodium, added sugars and saturated fats [42, 43]. In Italy, changes towards a healthier diet in young population showed a reduction in CO2 emissions larger than 50% [37]. In Germany, 14-20% of the environmental burdens resulted from food losses along the value chain, out-of-home consumption was responsible for 8-28% impact, and animal products were shown to have caused the highest environmental burdens [41].

With respect to countries outside of Europe, findings differ. In the last few years, China has transitioned from staple-foods to non-staple foods and from plant-sourced foods to animal-sourced foods. Diets have suffered from globalization and become unhealthier and less sustainable, with meat and grains being the two dominant contributors to the carbon footprint. It has been proposed that returning to traditional dietary patterns would be a beneficial strategy to reduce environmental concerns, such as land use, GHG, etc. in China [33,34,35]. A similar situation has been observed in Uganda were urban residency and non-traditional dietary patterns have been negatively associated with environmentally sustainability compared to a more traditional (plant-based) dietary pattern [39]. On the contrary, in India, shifting to healthy guidelines has increased GHG emissions because the initial energy intake of the population was below recommendations, nonetheless, decreased environmental impacts were seen among those who currently meet dietary recommendations [40].

There are several studies focused on comparing the impact of changes in specific food products. Some studies have shown how diets with less animal products (beef, pork, poultry, and dairy products) and more plant-based products are beneficial for the environment [44,45,46,47] without compromising the health of the population and still meeting dietary recommendations [45, 46]. Women are more likely to consume ≤1 portion of meat a day compared with men and, also, females and older respondents (> 60 years) were more likely to hold positive attitudes towards animal welfare [44]. Studies that assessed specific foods founded that whole grain cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and olive oil have been associated with improved health and have the lowest environmental impacts. Fish was associated with good health but was not simultaneously associated with less environmental impact, although it had a markedly lower impacts than red and processed meats which were associated with the largest increases in disease risk and environmental concerns [48]. Specifically, vegetables have been seen as one of the lowest impact food products, but it has been highlighted that the place where they are cultivated is important. For example, in the UK, importing seasonal vegetables from other countries in Europe has a lower impact than UK vegetables cultivated in heated greenhouses, despite the required transportation [49]. The environmental impacts of baby foods have also been assessed showing that meat-based ingredients cause almost 30% of the impacts [50].

Apart from the type of food used, the total amount of energy intake consumed must be considered when assessing sustainability, as it has done in this study when adjusting CO2 emissions per 1 kg of food products. Murakami et al. showed how considering energy intake, the inverse relation between the diet quality and de greenhouse gas emissions became stronger, specifically when measurements were done with the Mediterranean Diet score [51].

While the relationship between food consumption and sustainability is acknowledged, many are still not willing to change. It is for this reason that the consumer perception has been investigated by several studies [52,53,54]. Possible strategies to increase adherence to sustainable dietary practices and meet the United Nations agenda 2030 goal, such as supporting vegetarian dietary practices [55, 56], increasing the consumption of pulses [57], sustainable food systems in schools [58] and other strategies [59], have been put in practice. However, the United Nations agenda 2030 goals, specifically the target for GHG emissions, has not yet been reached. Future studies investigating optimal dietary patterns for both health and the environment, as well as strategies for how to increase awareness and consciousness to support population-based change are warranted to achieve the needed goals to be more sustainable and respectful with others and with the planet.

Strengths and limitations

Recently, there has been an increase in research focusing on diet and sustainability. The current study contributes to the growing knowledge about an issue that is getting more importance every day. This is a strength of the present analyses, as it provides evidence to reinforce the health and sustainable impact of the Mediterranean diet. The large sample size used to calculate the dietary CO2 emissions is another strength. Moreover, once the CO2 calculations were done for each participant, an adjustment per kg of food product was done. This is a strength because it avoids the effect of the energy intake confounder. Calculating only the parameter of CO2 emissions for assessing the sustainability of a diet allows the impact to be observed independently from other parameters.

Limitations in relation to the present study also must be noted. This present analysis represents a cross-sectional study, and thus causal interferences cannot be established. Even though assessing CO2 alone is a strength, it can also be a limitation because of the lack of information representing the use of energy, land and water use, or other parameters which could be also used to assess sustainability. Finally, the population in this study was between 55 and 75 years old which might not make possible to extrapolate the results to a younger population.

Conclusions

The current study shows that Mediterranean Diet can also be environmental protective since it appeared to be inversely related with GHG emissions, specifically CO2 emissions. In general, the higher the adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, the lower the total CO2 emissions showing that the erMedDiet index could be used pollution level index in the future. Findings may help inform and support public health initiative and dietary guidelines, such that recommendations continue to encourage making changes to food choices to achieve a healthier diet for both the population and the environment.

Availability of data and materials

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval of the PREDIMED-Plus Steering Committee. There are restrictions on the availability of data for the PREDIMED-Plus trial, due to the signed consent agreements around data sharing, which only allow access to external researchers for studies following the project purposes. Requestors wishing to access the PREDIMED-Plus trial data used in this study can make a request to the PREDIMED-Plus trial Steering Committee chair: jordi.salas@urv.cat. The request will then be passed to members of the PREDIMED-Plus Steering Committee for deliberation.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CO2 :

-

Carbon Dioxide

- EVOO:

-

Extra Virgin Olive Oil

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- GHG:

-

Greenhouse gas

- GHGs:

-

Greenhouse gases

- MedDiet:

-

The Mediterranean Diet

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviations

- Q1:

-

Quartile 1

- Q2:

-

Quartile 2

- Q3:

-

Quartile 3

- Q4:

-

Quartile 4

- 17-item erMedDiet:

-

17-item energy-restricted Mediterranean dietary questionnaire

References

United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goals. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/es/goals (Accessed on 19 Nov 2021).

Tilman D, Clark M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature. 2014;515(7528):518–22.

United Nations (UN). Food systems account for over one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions. Available from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1086822#:~:text=Food%20production%20the%20leading%20contributor,is%20expected%20to%20continue%20growing (Accessed on 19 Nov 2021).

Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393:447–92.

Burlingame B, Dernini S. Sustainable diets and biodiversity: directions and solutions for policy, research and action: proceedings of the intenational scientific symposium Biodiversity and sustainable diets united against hunger. Rome: FAO Headquarters; 2010. https://www.fao.org/3/i3004e/i3004e.pdf (Accessed on 19 Nov 2021)

Salas-Salvadó J, Díaz-López A, Ruiz-Canela M, Basora J, Fitó M, Corella D, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention program with energy-restricted Mediterranean diet and exercise on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: one-year results of the PREDIMED-plus trial. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):777–88.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística INE. Defunciones según causa de muerte. 2020. Available from: https://www.ine.es/mapas/svg/indicadoresDefuncionCausa.htm (Accessed on 19 Nov 2021).

World Heart Federation. What is cardiovascular disease? Available from: https://world-heart-federation.org/what-is-cvd/ (Accessed on 19 Nov 2021).

MacDiarmid JI. Is a healthy diet an environmentally sustainable diet? Proc Nutr Soc. 2013;72(1):13–20.

Martínez-González MA, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, Bulló M, Fitó M, Vioque J, et al. Cohort profile: design and methods of the PREDIMED-plus randomized trial. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(2):387–388o.

Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5.

Willet W. Nutritional epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Fernández-Ballart JD, Piñol JL, Zazpe I, Corella D, Carrasco P, Toledo E, et al. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(12):1808–16.

Martin-Moreno JM, Boyle P, Gorgojo L, Maisonneuve P, Fernandez-Rodriguez JC, Salvini S, et al. Development and validation of a food frequency questionnaire in Spain. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(3):512–9.

de La Fuente-Arrillaga C, Vzquez Ruiz Z, Bes-Rastrollo M, Sampson L, Martinez-González MA. Reproducibility of an FFQ validated in Spain. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(9):1364–72.

Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L, Cuadrado C. Tablas de composición de alimentos, guía de prácticas (Spanish Food Composition Tables). 17th ed. Madrid: Pirámide; 2015.

Mataix J, Mañas M, Llopis J, Martínez de Victoria E, Juan J, Borregón A. Tablas de Composición de Alimentos (Spanish Food Composition Tables). 5th ed. Granada: Universidad de Granada; 2013.

Hartikainen H, Pulkkinen H. Summary of the chosen methodologies and practices to produce GHGE-estimates for an average European diet Available from: http://luke.juvenesprint.fi (Accessed on 19 Nov 2021).

Schröder H, Zomeño MD, Martínez-González MA, Salas-Salvadó J, Corella D, Vioque J, et al. Validity of the energy-restricted Mediterranean diet adherence screener. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(8):4971–9.

Fresán U, Martínez-Gonzalez MA, Sabaté J, Bes-Rastrollo M. The Mediterranean diet, an environmentally friendly option: evidence from the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(8):1573–82.

Rosi A, Biasini B, Donati M, Ricci C, Scazzina F. Adherence to the mediterranean diet and environmental impact of the diet on primary school children living in Parma (Italy). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):1–14.

Fresán U, Martínez-González MA, Sabaté J, Bes-Rastrollo M. Global sustainability (health, environment and monetary costs) of three dietary patterns: results from a Spanish cohort (the SUN project). BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e021541.

Sáez-Almendros S, Obrador B, Bach-Faig A, Serra-Majem L. Environmental footprints of Mediterranean versus Western dietary patterns: beyond the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Available from: http://www.ehjournal.net/content/12/1/118 (Accessed on 19 Nov 2021).

Pairotti MB, Cerutti AK, Martini F, Vesce E, Padovan D, Beltramo R. Energy consumption and GHG emission of the Mediterranean diet: a systemic assessment using a hybrid LCA-IO method. J Clean Prod. 2015;103:507–16.

Grosso G, Fresán U, Bes-rastrollo M, Marventano S, Galvano F. Environmental impact of dietary choices: role of the mediterranean and other dietary patterns in an Italian cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1468.

Springmann M, Spajic L, Clark MA, Poore J, Herforth A, Webb P, et al. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: Modelling study. BMJ. 2020;370:m2322.

Reynolds CJ, Horgan GW, Whybrow S, Macdiarmid JI. Healthy and sustainable diets that meet greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and are affordable for different income groups in the UK. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(8):1503–17.

Macdiarmid JI, Kyle J, Horgan GW, Loe J, Fyfe C, Johnstone A, et al. Sustainable diets for the future: can we contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by eating a healthy diet? Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(3):632–9.

Springmann M, Wiebe K, Mason-D’Croz D, Sulser TB, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(10):e451–61.

Cobiac LJ, Scarborough P. Modelling the health co-benefits of sustainable diets in the UK, France, Finland, Italy and Sweden. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(4):624–33.

Martínez-González MA, García-Arellano A, Toledo E, Salas-Salvadó J, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, et al. A 14-item mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: the PREDIMED trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43134.

Chen C, Chaudhary A, Mathys A. Dietary change scenarios and implications for environmental, nutrition, human health and economic dimensions of food sustainability. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):856.

He P, Baiocchi G, Feng K, Hubacek K, Yu Y. Environmental impacts of dietary quality improvement in China. J Environ Manag. 2019;240:518–26.

Yin J, Yang D, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Cai T, Hao Y, et al. Diet shift: considering environment, health and food culture. Sci Total Environ. 2020;719:137484.

Xiong X, Zhang L, Hao Y, Zhang P, Chang Y, Liu G. Urban dietary changes and linked carbon footprint in China: a case study of Beijing. J Environ Manag. 2020;255:109877.

Vieux F, Perignon M, Gazan R, Darmon N. Dietary changes needed to improve diet sustainability: are they similar across Europe? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(7):951–60.

Donati M, Menozzi D, Zighetti C, Rosi A, Zinetti A, Scazzina F. Towards a sustainable diet combining economic, environmental and nutritional objectives. Appetite. 2016;106:48–57.

Broekema R, Tyszler M, van’t Veer P, Kok FJ, Martin A, Lluch A, et al. Future-proof and sustainable healthy diets based on current eating patterns in the Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(5):1338–47.

Auma CI, Pradeilles R, Blake MK, Holdsworth M. What can dietary patterns tell us about the nutrition transition and environmental sustainability of diets in Uganda? Nutrients. 2019;11(2):342.

Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJM, Harris F, Hillier J, Vetter SH, et al. Environmental impacts of dietary shifts in India: a modelling study using nationally-representative data. Environ Int. 2019;126:207–15.

Eberle U, Fels J. Environmental impacts of German food consumption and food losses. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2016;21(5):759–72.

Esteve-Llorens X, Moreira T, Feijoo G, González-García S. Linking environmental sustainability and nutritional quality of the Atlantic diet recommendations and real consumption habits in Galicia (NW Spain). Sci Total Environ. 2019;683:71–9.

Esteve-Llorens X, Darriba C, Moreira MT, Feijoo G, González-García S. Towards an environmentally sustainable and healthy Atlantic dietary pattern: life cycle carbon footprint and nutritional quality. Sci Total Environ. 2019;646:704–15.

Clonan A, Wilson P, Swift JA, Leibovici DG, Holdsworth M. Red and processed meat consumption and purchasing behaviours and attitudes: impacts for human health, animal welfare and environmental sustainability. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(13):2446–56.

Seves SM, Verkaik-Kloosterman J, Biesbroek S, Temme EHM. Are more environmentally sustainable diets with less meat and dairy nutritionally adequate? Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(11):2050–62.

Fresán U, Craig WJ, Martínez-González MA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Nutritional quality and health effects of low environmental impact diets: the “seguimiento universidad de Navarra” (sun) cohort. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):1–19.

Notarnicola B, Tassielli G, Renzulli PA, Castellani V, Sala S. Environmental impacts of food consumption in Europe. J Clean Prod. 2017;140:753–65.

Clark MA, Springmann M, Hill J, Tilman D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(46):23357–62.

Frankowska A, Jeswani HK, Azapagic A. Life cycle environmental impacts of fruits consumption in the UK. J Environ Manag. 2019;248:109111.

Sieti N, Schmidt Rivera XC, Stamford L, Azapagic A. Environmental sustainability assessment of ready-made baby foods: meals, menus and diets. Sci Total Environ. 2019;689:899–911.

Murakami K, Livingstone MBE. Greenhouse gas emissions of self-selected diets in the UK and their association with diet quality: is energy under-reporting a problem? Nutr J. 2018;17(1):27.

Macdiarmid JI, Douglas F, Campbell J. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite. 2016;96:487–93.

Rejman K, Kaczorowska J, Halicka E, Laskowski W. Do Europeans consider sustainability when making food choices? A survey of polish city-dwellers. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(7):1330–9.

Barone B, Nogueira RM, de Queiroz Guimarães KRLSL, Behrens JH. Sustainable diet from the urban Brazilian consumer perspective. Food Res Int. 2019;124:206–12.

Vergeer L, Vanderlee L, White CM, Rynard VL, Hammond D. Vegetarianism and other eating practices among youth and young adults in major Canadian cities. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(4):609–19.

Graça J, Truninger M, Junqueira L, Schmidt L. Consumption orientations may support (or hinder)transitions to more plant-based diets. Appetite. 2019;140:19–26.

Szczebyło A, Rejman K, Halicka E, Laskowski W. Towards more sustainable diets—attitudes, opportunities and barriers to fostering pulse consumption in polish cities. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1589.

Prescott MP, Burg X, Metcalfe JJ, Lipka AE, Herritt C, Cunningham-Sabo L. Healthy planet, healthy youth: a food systems education and promotion intervention to improve adolescent diet quality and reduce food waste. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1869.

Grasso AC, Hung Y, Olthof MR, Verbeke W, Brouwer IA. Older consumers’ readiness to accept alternative, more sustainable protein sources in the European Union. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1904.

Acknowledgements

We thank all PREDIMED-Plus participants and investigators. CIBEROBN, CIBERESP, and CIBERDEM are initiatives of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Madrid, Spain. The Hojiblanca (Lucena, Spain) and Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero (Madrid, Spain) food companies donated extra-virgin olive oil. The Almond Board of California (Modesto, CA), American Pistachio Growers (Fresno, CA), and Paramount Farms (Wonderful Company, LLC, Los Angeles, CA) donated nuts for the PREDIMED-Plus pilot study.

Funding

This work was supported by the official Spanish Institutions for funding scientific biomedical research, CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBEROBN) and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), through the Fondo de Investigación para la Salud (FIS), which is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (six coordinated FIS projects leaded by JS-S and JVi, including the following projects: PI13/00673, PI13/00492, PI13/00272, PI13/01123, PI13/00462, PI13/00233, PI13/02184, PI13/00728, PI13/01090, PI13/01056, PI14/01722, PI14/00636, PI14/00618, PI14/00696, PI14/01206, PI14/01919, PI14/00853, PI14/01374, PI14/00972, PI14/00728, PI14/01471, PI16/00473, PI16/00662, PI16/01873, PI16/01094, PI16/00501, PI16/00533, PI16/00381, PI16/00366, PI16/01522, PI16/01120, PI17/00764, PI17/01183, PI17/00855, PI17/01347, PI17/00525, PI17/01827, PI17/00532, PI17/00215, PI17/01441, PI17/00508, PI17/01732, PI17/00926, PI19/00957, PI19/00386, PI19/00309, PI19/01032, PI19/00576, PI19/00017, PI19/01226, PI19/00781, PI19/01560, PI19/01332, PI20/01802, PI20/00138, PI20/01532, PI20/00456, PI20/00339, PI20/00557, PI20/00886, PI20/01158); the Especial Action Project entitled: Implementación y evaluación de una intervención intensiva sobre la actividad física Cohorte PREDIMED-Plus grant to JS-S; the European Research Council (Advanced Research Grant 2014–2019; agreement #340918) granted to MÁM-G.; the Recercaixa (number 2013ACUP00194) grant to JS-S; grants from the Consejería de Salud de la Junta de Andalucía (PI0458/2013, PS0358/2016, PI0137/2018); the PROMETEO/2017/017 grant from the Generalitat Valenciana; the SEMERGEN grant. J.S-S is partially supported by ICREA under the ICREA Academia programme. S.K.N. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, # MFE-171207). None of the funding sources took part in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, or writing the report, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the principal PREDIMED-Plus investigators contributed to study concept and design and to data extraction from the participants. SG, and CB performed the statistical analyses. SG, CB, and JAT drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.K.N. is a volunteer member of the not-for-profit group Plant-Based Canada J.S.-S. reported receiving research support from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, the European Commission, the USA National Institutes of Health; receiving consulting fees or travel expenses from Eroski Foundation, and Instituto Danone, Spain, receiving nonfinancial support from Hojiblanca, Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero, Almond Board of California, and Pistachio Growers; serving on the board of and receiving grant support through his institution from the International Nut and Dried Foundation and the Eroski Foundation; and personal fees from Instituto Danone; Serving in the Board of Danone Institute International. D.C. reported receiving grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III. R.E. reported receiving grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fundación Dieta Meditarránea and Cerveza y Salud and olive oil for the trial from Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero and personal fees from Brewers of Europe, Fundación Cerveza y Salud, Interprofesional del Aceite de Oliva, Instituto Cervantes in Albuquerque, Milano and Tokyo, Pernod Ricard, Fundación Dieta Mediterránea (Spain), Wine and Culinary International Forum and Lilly Laboratories; non-financial support from Sociedad Española de Nutrición and Fundación Bosch y Gimpera; and grants from Uriach Laboratories. The rest of the authors have declared that no competing interests exist. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

García, S., Bouzas, C., Mateos, D. et al. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and adherence to Mediterranean diet in an adult population: the Mediterranean diet index as a pollution level index. Environ Health 22, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00956-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00956-7