Abstract

Background

Recent studies showed that air pollution might play a role in the etiology of mental disorders. In this study we evaluated the association between air pollution and mental and self-rated health and the possible mediating effect of physical activity in this association.

Methods

In 2008, 2013 and 2018 the Belgian Health Interview Survey (BHIS) enrolled 16,455 participants who completed following mental health dimensions: psychological distress, suboptimal vitality, suicidal ideation, and depressive and generalized anxiety disorder and self-rated health. Annual exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulate matter ≤ 2.5 µm (PM2.5) and black carbon (BC) were estimated at the participants’ residence by a high resolution spatiotemporal model. Multivariate logistic regressions were carried out taking into account a priori selected covariates.

Results

Long-term exposure to PM2.5, BC and NO2 averaged 14.5, 1.4, and 21.8 µg/m3, respectively. An interquartile range (IQR) increment in PM2.5 exposure was associated with higher odds of suboptimal vitality (OR = 1.27; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.42), poor self-rated health (OR = 1.20; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.32) and depressive disorder (OR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.41). Secondly, an association was found between BC exposure and higher odds of poor self-rated health and depressive and generalized anxiety disorder and between NO2 exposure and higher odds of psychological distress, suboptimal vitality and poor self-rated health. No association was found between long-term ambient air pollution and suicidal ideation or severe psychological distress. The mediation analysis suggested that between 15.2% (PM2.5-generalized anxiety disorder) and 40.1% (NO2-poor self-rated health) of the association may be mediated by a difference in physical activity.

Conclusions

Long-term exposure to PM2.5, BC or NO2 was adversely associated with multiple mental health dimensions and self-rated health and part of the association was mediated by physical activity. Our results suggest that policies aiming to reduce air pollution levels could also reduce the burden of mental health disorders in Belgium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mental health has been defined by the WHO as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” [1]. World-wide, 14% of the global burden of all diseases can be attributed to mental, neurological, and substance use disorders [2]. Mental health is associated with multiple personal determinants, including gender [3], social support [4], physical activity [5] and socio-economic status [6]. Besides these well-known risk factors, environment is also important in this context [7] as increasing evidence suggests that higher levels of air pollution might affect mental health. Long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and fine (≤ 2.5 µm (PM2.5)) and coarse (≤ 10 µm (PM10)) particulate matter has been associated with increased odds of depressive disorder [8,9,10]. Additionally, exposure to PM2.5 was associated with increased symptoms of anxiety disorder [11]. Finally, several studies showed a higher risk of suicidal ideation and suicide death among people exposed to higher long-term [12, 13] and short-term air pollution [14,15,16] concentrations.

Studies on this topic often include only one mental health outcome or one type of air pollutant. However, mental health is a broad concept and different air pollutants might induce different effects. For example, NO2 and black carbon (BC) are known as traffic-related air pollutants whereas PM2.5 is a complex multi-pollutant mixture of solid and liquid particles. As traffic only represents part of the PM exposure, the effects of PM might differ from the traffic-related pollutants [17, 18]. Therefore, in the first objective of this large cross-sectional study, we assessed self-rated health and multiple dimensions of mental health, i.e., psychological and severe psychological distress, suboptimal vitality, suicidal ideation, and depressive and generalized anxiety disorder in association with long-term exposure to PM2.5, BC and NO2.

Furthermore, research showed that higher concentrations of air pollution may be adversely associated with physical activity as air pollution could make a neighborhood environment less appealing for outdoor recreation [19]. In turn, being less active might negatively affect the mental health status [20, 21]. As shown by several reviews and meta-analyses, long-term exercise has anti-inflammatory effects [22], is protective against oxidative stress [23], promotes self-perception [24], and improves body image [25], which all positively affects mental health [20]. Also, during physical activity one might be exposed to higher air pollution concentrations, due to for example higher respiration rates [26]. This could diminish the positive effect of physical activity. However, research showed that the benefits of active travel outweighed the harm caused by air pollution, except for the most extreme concentrations [27]. As research on the topic of physical activity and air pollution is very limited, as a second objective, we evaluated the mediation effect of physical activity in the association between air pollution and mental and self-rated health. Our hypothesis is that exposure to higher air pollution concentrations is adversely associated with mental and self-rated health and that part of this association might be mediated by physical activity.

Methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study is executed on a subsample of the Belgian Health Interview Survey (BHIS) of 2008, 2013 and 2018. The sampling frame of the BHIS was the Belgian National Register and participants were selected based on a multistage stratified sampling design including a geographical stratification, a selection of municipalities within provinces, of households within municipalities, and of respondents within households [28]. The participation rate of the households in 2008, 2013 and 2018 was respectively 55.0%, 57.0%, and 57.5%.

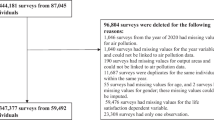

In 2008, 2013 and 2018, in total 26,272 BHIS participants were eligible to complete the mental health modules (participants who participated through a proxy respondent (a person of confidence filled out the survey) or under 15 years old were not eligible). Our main analysis included 16,455 participants: as (1) data on air pollution and moving history of 581 participants was not available, (2) persons living less than one year on the current address were excluded (n = 2,984), and (3) participants who did not answer all mental and self-rated health questions and completed all information used as covariates in this study were excluded (n = 5,717 and 535, respectively), see flowchart in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Supplementary Table 1 shows the characteristics of the original 26,272 BHIS participants. Slightly more participants of Flanders and less of the Brussels Capital Region and more participants born in Belgium and with a higher educational level in the household were included. No other differences were found.

Health interview survey

The BHIS is a comprehensive survey which aims to gain insight in the health status, health behavior and medical consumption of the Belgian population. The questions on mental health were based on international standardized and validated questionnaires [29]. Detailed information on each indicator score and its use is addressed in Supplementary Table 2.

According to the WHO, mental health includes the absence of mental illnesses but also the positive dimensions of mental health [1]. For the first part, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) aims at screening psychological wellbeing and detects possible disorders in general whereas the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) focusses specifically on depressive and anxiety disorder. For the second part, the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) contains 4 questions related to energy and vitality. More specifically, firstly, the GHQ-12 provides the prevalence of psychological and severe psychological distress in the population [30]. On the total GHQ-score cut-off points of 2 or more and 4 or more were used to identify respectively psychological and severe psychological distress. Secondly, four questions of the SF-36 indicate the participant’s vital energy level [31]. We used a cut-off point to identify those participants with an optimal vitality score, which is a score equal to or above the standard deviation above the mean, as used in previous studies [32, 33]. The standardized Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the four questions related to vitality based on the SF-36 and for the GHQ-12 questionnaire were respectively 0.79 and 0.89.

Over the BHIS data collection years, there have been changes in the selection of instruments for assessing depressive and generalized anxiety disorder. Therefore, the indicators based on these instruments were evaluated in a subset containing only the participants of 2008 and 2013 (n = 10,153). In these years, the SCL-90-R questionnaire was used. A score higher than 1 identified those participants who suffer from depressive or generalized anxiety disorder [34]. The standardized Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the SCL-90-R scales for generalized anxiety disorder and depressive disorder were respectively 0.90 and 0.92.

Other indicators in the BHIS were based on single questions. Firstly, a dichotomous question on suicidal ideation in the past 12 months was used: “Have you ever seriously thought of ending your life?”; “If yes, did you have such thoughts in the past 12 months?”. Secondly, the question “How is your health in general? Is it very good, good, fair, poor, or very poor?” was used to indicate self-rated health [35]. The answer categories were dichotomized into good self-rated health (very good to good) and poor self-rated health (fair, poor, and very poor). Finally, the BHIS also included personal, socio-economic and lifestyle information.

Air pollution assessment

Residential addresses of the participants were geocoded. Daily residential exposure (µg/m3) to PM2.5, BC and NO2 at the participants’ residence was modelled at high resolution using a spatiotemporal interpolation model [36]. This model included air pollution data from the Belgian fixed monitoring stations and CORINE Land Cover (CLC) information obtained by satellites in combination with a dispersion model including point and line sources [37,38,39]. The overall model performance was evaluated by leave-one-out cross-validation and was based on 34 monitoring points for PM2.5, 44 for NO2 and 14 for BC. The temporal and spatial variability of the model was explained by 80% for PM2.5 [39], 78% for NO2 [39] and 74% for BC [38]. Furthermore, during a previous study, we validated the modelled exposure by measuring the internal carbon as urinary carbon particles, showing that the internal carbon exposure is correlated with the chronic residential carbon exposure (partial r = 0.17, CI: 0.05 to 0.28) [40]. We used the daily modelled exposure values obtained by this model to calculate the residential exposure during the year of participation. Because the high resolution model was not available for the year 2008, the data of 2009–10 was used as a representative for the spatial contrast of the earlier period. Evidence showed that the spatial distribution of particulate air pollution is stable over a decade and that existing land use regression models are good predictors of historical spatial contrasts [41,42,43,44].

Covariates and mediators

Covariates included in the models were age (continuous), gender (male; female), year of participation (2008; 2013; 2018), region (Flanders; Brussels Capital Region; Wallonia), highest educational level of the household (up to lower secondary; higher secondary; college or university), country of birth (Belgian; EU; non-EU), household composition (single; one parent with child(ren); couple without child(ren); couple with child(ren); other) and smoking status (current smoker; current non-smoker). To capture the non-linear effect of age, we included a quadratic term when the result of the analysis showed that both the linear and quadratic term were significant.

Physical activity was based on the question ‘What describes best your leisure time activities during the last year?’ Possible answer categories were: (1) Hard training and competitive sport more than once a week; (2) Jogging and other recreational sports or gardening, 4 h or more per week; (3) Jogging and other recreational sports or gardening, less than 4 h per week; (4) Walking, bicycling or other light activities 4 h or more a week; (5) Walking, bicycling or other light activities less than 4 h a week; and (6) Reading, watching TV or other sedentary activities. Category 1 to 5 were combined to present active lifestyle whereas category 6 represents sedentary lifestyle. A directed acyclic graph including all covariates and the mediator is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Statistical analysis

We performed single exposures multivariate logistic regressions taking into account the previously mentioned a priori selected covariates. Furthermore, we accounted for the complex survey design by including clustering and stratification in the model. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated to assess possible multi-collinearity between the explanatory variables. A VIF value of 5 was used as threshold. All results are presented as the odds ratio (95% CI) of having a mental health condition or disorder or a poor-self rated health for an IQR increment in air pollution exposure. Chi-squared tests (categorical data) and t-tests (continuous data) were used to evaluate differences in characteristics between participants with and without psychological distress.

In a secondary analysis, we performed a mediation analysis to determine whether physical activity was a potential mediator of the association between air pollution and mental and self-rated health. This analysis was performed on a subset of 14,899 participants. The direct effect (DE), indirect effect (IE), total effect (TE) and proportion mediated were estimated using the CAUSALMED procedure in SAS, in a counterfactual framework, based on the SAS macro by Valeri and VanderWeele [45]. PROC CAUSALMED estimates effects after maximum likelihood estimation and uses the delta method to estimate the standard errors. An interaction term between exposure and mediator was included in the model. When assumptions of the mediation analysis hold, the DE represents the effect of air pollution exposure on mental or self-rated health independent from physical activity and the IE represents the estimated effect of air pollution exposure operating through physical activity [45]. The covariates for which we adjusted in the mediation models were as same as in the main models. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). GIS analyses to calculate green space were carried out using ArcGIS 10 software.

Sensitivity analysis

In a first sensitivity analysis, models were additionally adjusted for urbanization level (big cities/dense agglomerations; suburban areas; urbanized municipalities; rural areas), physical activity (active lifestyle; sedentary lifestyle), and green space in a buffer of 1000 m around the participants’ residence (continuous), separately. Physical activity [46] is known to be associated with mental health whereas urbanization level [47] and green space [48] are known to be associated with air pollution. Green space was calculated with Corine land Cover data of 2012 (European Environment Agency) and included the classes of forest and semi natural areas, wetlands, water bodies and artificial, non-agricultural vegetated areas.

Secondly, the SF-36 and SCL-90-R questionnaires were used with one cut-off point. In a second sensitivity analysis, we evaluated the effect of air pollution on the continuous scale of the SF-36. Linear regressions were performed adjusted for the same covariates as the main analyses and taking into account clustering and stratification. For the SCL-90-R no normal distributed residuals were found. Therefore, we divided the score in tertiles and evaluated those three groups, using the same model as for the main analyses. Class 0 indicates the lowest scores, class 2 indicates the highest scores.

Finally, in a third sensitivity analysis, to evaluate effect modification by age, gender and socio-economic status (highest educational level of the household), interaction terms for these covariates with the exposure were added separately to the models. Stratification was done when the interaction term showed a significance ≤ 0.10. As age was used as a continuous parameter, four groups were made for stratification (15–29; 30–44; 45–59; + 60).

Results

Population characteristics

The characteristics of the 16,455 participants included in this study are presented in Table 1. Out of all participants, 47.5% were men and the average age ± SD was 50.3 ± 18.9 years. The table also shows large differences in characteristics between participants with and without psychological distress.

Population data from the survey years indicate that the average age of the Belgian population over 15 years old was 47.6 (19.5), 48.7% were men and the distribution over Flanders, Brussels Capital Region and Wallonia was respectively 58.1%, 10.0%, 31.9%. The distribution of our sample according to age and gender thus largely corresponds to the Belgian 15 + population figures. The difference in the regional distribution is due to the oversampling of the Brussels Capital Region in the BHIS. Table 2 shows the prevalence of each of the mental health dimensions and self-rated health.

Air pollutant exposure levels

The air pollutant exposure levels are presented in Table 3. The average annual PM2.5, BC and NO2 concentrations (IQR) were respectively 14.5 (3.8) µg/m3, 1.4 (0.6) µg/m3 and 21.8 (10.8) µg/m3. The air pollutants were highly correlated. The Spearman correlation coefficients between PM2.5 and BC, PM2.5 and NO2 and BC and NO2 were respectively 0.86 (p < 0.0001), 0.74 (p < 0.0001) and 0.85 (p < 0.0001).

Air pollution and mental and self-rated health

All results are presented in Fig. 1 and estimates are available in Supplementary Table 3. Firstly, our results showed significant associations between long-term PM2.5 exposure and various mental health outcomes and self-rated health. Each 3.8 µg/m3 increment in long-term PM2.5 (IQR contrast) was associated with increased odds of suboptimal vitality (OR = 1.27; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.42), poor self-rated health (OR = 1.20; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.32) and depressive disorder (OR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.41). Secondly, an IQR increment in BC (0.6 µg/m3) was associated with increased odds of poor self-rated health (OR = 1.09; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.15), depressive disorder (OR = 1.08; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.17) and generalized anxiety disorder (OR = 1.09; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.20). Finally, we found for an IQR increment in NO2 exposure (10.8 µg/m3) increases in the odds of psychological distress (OR = 1.06; 95% CI: 0.99,1.14), suboptimal vitality (OR = 1.13; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.23) and poor self-rated health (OR = 1.14 95% CI; 1.06, 1.22). No association was found between long-term ambient air pollution and suicidal ideation or severe psychological distress. The average VIF value was 1.43.

Odds ratios (with 95% CI) of all mental health dimensions and self-rated health for an IQR increment in annual PM2.5, NO2 or BC concentration. Estimates were adjusted for age, gender, year of participation, region, country of birth, household composition, smoking status, highest educational level of the household and the quadratic term of age when both the linear and quadratic term were significant. *p ≤ 0.05. IQRs for PM2.5, BC, and NO2 were respectively 3.8 µg/m3, 0.6 µg/m3 and 10.8 µg/m3

Mediation analysis

A mediation analysis was conducted to evaluate the potential indirect effect of physical activity in the association between air pollution and the indicators of mental health and self-rated health. For all studied ambient pollutants, higher levels were associated with higher odds of having a sedentary lifestyle. Secondly, for all mental health outcomes and self-rated health, the results showed that the odds of having a mental health condition or disorder or having a poor self-rated health was higher for those having a sedentary lifestyle (Suppl. Table 4). The results of the mediation analysis suggested that between 15.2% and 40.1% (Fig. 2) of the association between air pollution (mostly PM2.5) and mental or self-rated health was mediated by physical activity, with exception of severe psychological distress and suicidal ideation (Suppl. Table 5). The strongest mediation effect was found for the association between BC and NO2 and poor self-rated health: 40.1% (95% CI: 6.4%, 73.7%) and 40.1% (95% CI: 14.6%, 65.5%), respectively.

Estimated effect of air pollution exposure on mental health and self-rated health mediated through physical activity. The figure displays air pollution (PM2.5, BC or NO2) as treatment, physical activity as mediator and mental or self-rated health as outcome (A psychological distress, B suboptimal vitality, C poor self-rated health, D depressive disorder, E generalized anxiety disorder). The figure shows the odds ratios (95% CI) of the indirect effect (IE) and the direct effect (DE), and the proportion of mediation. The mediation model was adjusted for age, gender, year of participation, region, country of birth, household composition, smoking status and highest educational level of the household

Sensitivity analysis

In a sensitivity analysis, additional adjustment for physical activity, urbanization level, or green space did not change the effect direction observed in our main analyses (Suppl. Table 3). However, additional adjustment for physical activity resulted in loss of significance in multiple associations and additional adjustment for urbanization showed higher odds for generalized anxiety disorder when exposed to an IQR increase in PM2.5 (OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.71).

Secondly, when evaluating the SF-36 score continuously, an IQR increase in PM2.5, BC and NO2 was associated with respectively a -2.40 (95% CI: -3.13, -1.67, p < 0.0001), -0.83 (95% CI: -1.31, -0.36, p = 0.0005), and -1.48 (95% CI: -2.04, -0.94, p < 0.0001) lower vitality score. This is in line with the associations based on the dichotomous score. Also, when evaluating depressive and generalized anxiety disorder in tertiles, an IQR increment in PM2.5 was associated with higher odds of being in class 1 (OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.30) and class 2 (OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.32) compared with class 0 for depressive disorder. For the same exposure, a trend indicates higher odds of being in class 2 (OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 0.95, 1.95) compared with class 0 for anxiety disorder (Suppl. Table 6).

Finally, results of effect modification can be found in Supplementary tables 7-9. Firstly, the association between poor self-rated health and both PM2.5 and BC and between severe psychological distress and PM2.5 was mainly driven by the elderly (+ 60 years). Secondly, the association between PM2.5 and depressive and generalized anxiety disorder was stronger for women compared with men whereas the opposite was found for the association between psychological distress and PM2.5 and NO2. Finally, no clear indication for effect modification by socio-economic status could be demonstrated.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that long-term ambient residential air pollution exposure was associated with different dimensions of mental health and self-rated health in the Belgian population. Furthermore, our results indicated that part of the association between air pollution and mental or self-rated health was mediated by physical activity and that the association between mental health outcomes and air pollution was stronger in elderly and in women. All discussed literature for each mental health outcome is combined in Supplementary Table 10.

Air pollution and mental health

Our first results showed higher odds of psychological distress for a higher NO2 exposure. Only a few studies previously evaluated this association. In a fully-adjusted model, exposure to higher annual PM2.5 concentrations was associated with a higher level of psychological distress (β = 0.185; 95% CI: 0.079, 0.290), but for NO2, only an effect was found in the unadjusted analysis [49]. In another study in an adult population, for each IQR increment in long-term exposure to PM2.5 (0.82 µg/m3) and NO2 (7.85 µg/m3), the odds ratio of severe psychological distress was respectively 1.08 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.11) and 1.08 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.11) [50]. The different outcomes between our study and the two previously mentioned studies cannot be explained by the pollutant concentrations as these were similar as for our study. Also, these studies used the Kessel Psychological Distress Scale while we used the GHQ-12 questionnaire, but research showed that both questionnaires were positively associated [51].

Secondly, we found no significant association between long-term air pollution and suicidal ideation. Until now 11 studies assessed suicide in association with short-term air pollution [14, 15, 52], two studies with long-term air pollution [12, 13] and three studies included different time periods [53, 54]. In a study in Belgium, during summer, people were more likely to commit suicide when PM10 and ozone concentrations were high [14]. However, Casas et al. [14] showed acute effects while in this study the focus was long-term exposure to air pollution. In a study in South-Korea, where participants were followed up from 2002 until 2013 and were 564 (0.2%) participants died from suicide in this period, the risk of suicide was higher in the highest quartile for long-term PM10 (Hazard ratio = 4.03; 95% CI: 2.97, 5.47) and in the third quartile for annual NO2 (Hazard ratio = 1.52; 95% CI: 1.17, 1.96) compared with the lowest level of the air pollutants [12]. In another Korean study, yearly average exposure to the highest quartile of NO2 was associated with increased odds of suicidal ideation for men and women (OR = 1.32; 95% CI: 1.18, 1.48 and OR = 1.40; 95% CI: 1.29, 1.53 respectively) compared with the reference quartile. Similar results were found for PM10 [13]. One of the reasons why we did not find an association might be the low prevalence of suicidal ideation in our study population (4.4%) while in the study of Shin et al. (2018) this was 8.8% [13].

Thirdly, our results showed higher odds of suboptimal vitality with increasing PM2.5, BC and NO2 exposure. Similarly, Yamazaki and colleagues (2006) showed a significant linear association between one month exposure to ambient photochemical oxidants (Ox), and a lower vitality score, according to the four questions in the SF-36 questionnaire on vitality [55]. However, the association with suspended particulate matter was only found for the crude analysis and no association was found for NOx.

Fourthly, we observed a positive association between the air pollutants and depressive disorder. This is in line with the conclusions of several systematic reviews [7, 56,57,58]. Additionally, in a subpopulation of 958 adults living in Barcelona, long-term NO2 and PM2.5 exposure was positively associated with depressive disorder, i.e., each 5 µg/m3 increment in PM2.5 was associated with increased odds of depressive disorder of 4.38 (95% CI: 1.70, 11.30) [10]. Also, in a 3-year follow-up study on elderly in Korea, an IQR increment in 3-day moving average of PM10 was associated with a 17% (95% CI: 4.9%, 30.5%) increment in the depression score [59]. In our study, the association between PM2.5 and depressive disorder was mainly driven by the women. Both previously mentioned studies did not evaluate effect modification by gender but their study populations included a high percentage of women (63.9% and 74% respectively).

Finally, we found that higher exposure to PM2.5 and BC was associated with higher odds of generalized anxiety disorder but this association was less clear for NO2. Previous literature is inconclusive. Two studies found significant associations between PM2.5 and anxiety disorder [8, 11], whereas Vert et al. [10] found no association of PM2.5, PM10 or NO2 exposure with anxiety disorder [10]. The use of different questionnaires might explain the different results. Also, differences might be explained by the study design as Vert et al. (2017), Pun et al. (2017) and Power et al. (2015) used respectively a cross-sectional, a longitudinal and a cohort study design. Furthermore, the latter included only women, which as mentioned previously, tend to have more mental health issues compared with men [60].

Air pollution and self-rated health

All three air pollutants were positively associated with poor self-rated health. Nakao and colleagues (2019) found comparable results, i.e., one month exposure to higher NO2 concentrations and suspended particulate matter in Japan was significantly associated with a decreased overall health score. However, the association with NO2 was only present in one of the two explored cities and no association was found with PM2.5 [61]. Also, their participants ranged between 40 and 79 years old. This is consistent with our findings as our sensitivity analysis showed that the association between PM2.5 and BC and self-rated health was mainly driven by the elderly.

Biological mechanisms

How air pollution might affect mental or self-rated health is still not fully understood. Animal studies have shown that particles can be transferred to the brain. For example, after 12 days of exposure to manganese oxide ultra-fine particles, the concentrations increased 3.5-fold in the olfactory bulb and to a lesser extent in other brain regions of rats [62]. Furthermore, a study in Mexico City showed elevated levels of inflammatory markers in the brain of children when exposed to higher concentrations of air pollution [63, 64]. The translocation of the particles to the brain can be explained by two hypotheses. They can either access the brain through the blood–brain barrier after they deposit in the lungs and translocate to the blood circulation or they can travel via the olfactory nerve after they deposit on the nasal olfactory mucosa [65, 66]. Via the olfactory nerve, odor information is sent to the olfactory bulb and the brain. The amygdala and hippocampus, which process odor information, are also part of the limbic system and thus responsible for emotion regulation [67, 68]. Through this connection, it is believed that odors can regulate mood and behavior [67]. Consequently, air pollution particles might affect the olfactory pathway and also modulate emotion regulation. However, research is warranted to support this theory.

Mediation analysis

The results of our sensitivity analysis showed that after adjusting for physical activity, the significant associations between air pollution and mental or self-rated health were lost. This indicates that physical activity is a strong moderator in our study setup and could imply that the benefits of physical activity on mental health outweigh the harm caused by air pollution [27, 69]. Further investigation indicated that both the exposures and outcomes were strongly associated with physical activity. A higher exposure to air pollution was associated with a less active lifestyle, which in turn was associated with a poor mental health outcome. The results of our mediation analysis showed that a considerable proportion of the association between air pollution and mental and self-rated health was mediated by physical activity. Similar results were found by Wang et al. (2019) where the mediation of physical activity was evaluated in the association between PM2.5 and depression [9]. Another study showed no direct association between air pollution and general mental health but it was indirectly associated through annoyance, restorative quality, and physical activity, working in serial [70].

Importantly, caution is advised when interpreting these results. Firstly, the association between physical activity and mental health has been evaluated in multiple studies [20, 21] but it is not straight forward as it can go in both directions. A sedentary lifestyle might induce mental health disorders, whereas people with mental health disorders might be less willing to engage in physical activity. As mediation analysis assumes causality [45] and most, but still weak, evidence suggests the first hypothesis [71, 72], we assumed that physical activity affects mental health. Still, further research is warranted to prove causality of this association.

Secondly, only few studies evaluated the association between air pollution and physical activity [73,74,75,76] and the pathways are still unclear. Three hypothesis for this association are proposed in the reviews of Tainio et al. [19] and An et al. [77]. Firstly, media alerts and health professionals informing the public about daily changes in air pollution levels might change day-to-day decisions on physical activity [78]. Secondly, air pollution adversely affects respiratory and cardiovascular health [79, 80] which may result in a reduced exercise capacity and performance [81, 82]. Finally, visible air pollutants like smog might discourage people from engaging in outdoor physical activity [74]. Important to notice is that most of the limited evidence is based on the U.S. and China where air pollution concentrations may be higher compared with Belgium. Further research on this matter in Western Europe is warranted.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is the use of a large dataset and while other studies often only assess one mental health outcome, we were able to evaluate multiple mental health dimensions and self-rated health, based on validated tools. Also, we assessed three different air pollutants that were estimated with a high-resolution spatiotemporal model.

We also acknowledge some limitations of this study. Because the high resolution model was not available for the year 2008, the data of 2009–10 was used as a representative for the spatial contrast of the earlier period. Evidence showed that the spatial distribution of particulate air pollution is stable over a decade and that existing land use regression models are good predictors of historical spatial contrasts [41,42,43,44]. Furthermore, as air pollution is measured at the participants’ residence, risks might be underestimated due to exposure misclassification depending on their mobility or behavior pattern [83]. However, previously we have found that urinary particle load reflected the residential air pollution exposure [40]. Secondly, we did not adjust for noise, which can also affect mental health [84]. Data on noise was not available for this project and furthermore, this is measured differently in the different regions of Belgium. Finally, a limitation of this research is that the mediation model assumes causality, i.e. that physical activity precedes mental health. However, as mentioned in the discussion, the association between physical activity and mental health might be bidirectional. Due to the cross-sectional study design, it is not possible to identify the direction of the effect but only to identify associations.

Conclusion

Our data support the association between long-term exposure to PM2.5, BC and NO2 and a poor mental and self-rated health status. Furthermore, we showed that part of the association can be explained by physical activity. Our results suggest that both lifestyle factors and environment exposures should be taken into account to improve mental health. Due to some inconsistency in the results and the limitations of our study design, future studies are warranted to confirm our results.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used for this study is available through a request to the Health Committee of the Data Protection Authority.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Black Carbon

- CI:

-

Confidence Intervals

- CLC:

-

Corine Land Cover

- GHQ-12:

-

General Health Questionnaire

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- NO2 :

-

Nitrogen dioxide

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio; PM2.5: Particulate matter ≤ 2.5 µm

- SF-36:

-

Short Form Health Survey

- SCL-90-R:

-

Symptom Checklist 90 Revised

References

World Health Organization. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice (summary report). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Lindert J, Bilsen J, Jakubauskiene M. Public mental health. European Journal of Public Health. 2017;27(suppl_4):32–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx163.

Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, Berglund P, Bromet EJ, Brugha TS, et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):785–95. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36.

Wang RAH, Davis OSP, Wootton RE, Mottershaw A, Haworth CMA. Social support and mental health in late adolescence are correlated for genetic, as well as environmental, reasons. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13088. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13449-2.

Mikkelsen K, Stojanovska L, Polenakovic M, Bosevski M, Apostolopoulos V. Exercise and mental health. Maturitas. 2017;106:48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.09.003.

Bøe T, Øverland S, Lundervold AJ, Hysing M. Socioeconomic status and children’s mental health: results from the Bergen Child Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(10):1557–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0462-9.

van den Bosch M, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Environmental exposures and depression: biological mechanisms and epidemiological evidence. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:239–59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044106.

Pun VC, Manjourides J, Suh H. Association of ambient air pollution with depressive and anxiety symptoms in older adults: results from the NSHAP study. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(3):342–8. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP494.

Wang R, Liu Y, Xue D, Yao Y, Liu P, Helbich M. Cross-sectional associations between long-term exposure to particulate matter and depression in China: the mediating effects of sunlight, physical activity, and neighborly reciprocity. J Affect Disord. 2019;249:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.007.

Vert C, Sánchez-Benavides G, Martínez D, Gotsens X, Gramunt N, Cirach M, et al. Effect of long-term exposure to air pollution on anxiety and depression in adults: A cross-sectional study. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017;220(6):1074–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.06.009.

Power MC, Kioumourtzoglou MA, Hart JE, Okereke OI, Laden F, Weisskopf MG. The relation between past exposure to fine particulate air pollution and prevalent anxiety: observational cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350: h1111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1111.

Min J-y, Kim H-J, Min K-b. Long-term exposure to air pollution and the risk of suicide death: A population-based cohort study. Science of the Total Environment. 2018;628–629:573–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.011.

Shin J, Park JY, Choi J. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollutants and mental health status: A nationwide population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13(4): e0195607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195607.

Casas L, Cox B, Bauwelinck M, Nemery B, Deboosere P, Nawrot TS. Does air pollution trigger suicide? A case-crossover analysis of suicide deaths over the life span. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(11):973–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0273-8.

Yang C-Y, Huang Y-T, Chiu H-F. Does ambient ozone air pollution trigger suicide attempts? A case cross-over analysis in Taipei. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2019;82(10):638–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2019.1640980.

Ng CFS, Stickley A, Konishi S, Watanabe C. Ambient air pollution and suicide in Tokyo, 2001–2011. J Affect Disord. 2016;201:194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.006.

Kim K-H, Kabir E, Kabir S. A review on the human health impact of airborne particulate matter. Environ Int. 2015;74:136–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2014.10.005.

De Kok TM, Driece HA, Hogervorst JG, Briedé JJ. Toxicological assessment of ambient and traffic-related particulate matter: a review of recent studies. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research. 2006;613(2–3):103–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrrev.2006.07.001.

Tainio M, Andersen ZJ, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Hu L, de Nazelle A, An R, et al. Air pollution, physical activity and health: A mapping review of the evidence. Environ Int. 2020;147: 105954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105954.

Kandola A, Ashdown-Franks G, Hendrikse J, Sabiston CM, Stubbs B. Physical activity and depression: towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;107:525–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.040.

Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Hallgren M, Firth J, Richards J, Schuch F, et al. Physical activity and anxiety: A perspective from the World Health Survey. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:545–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.028.

Pedersen BK. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2017;47(8):600–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12781.

de Sousa CV, Sales MM, Rosa TS, Lewis JE, de Andrade RV, Simões HG. The Antioxidant Effect of Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medecine. 2017;47(2):277–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0566-1.

Feuerhahn N, Sonnentag S, Woll A. Exercise after work, psychological mediators, and affect: A day-level study. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2014;23(1):62–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.709965.

Campbell A, Hausenblas HA. Effects of exercise interventions on body image: a meta-analysis. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(6):780–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105309338977.

Bigazzi AY, Figliozzi MA. Review of urban bicyclists’ intake and uptake of traffic-related air pollution. Transp Rev. 2014;34(2):221–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2014.897772.

Tainio M, de Nazelle AJ, Götschi T, Kahlmeier S, Rojas-Rueda D, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, et al. Can air pollution negate the health benefits of cycling and walking? Prev Med. 2016;87:233–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.002.

Demarest S, Van der Heyden J, Charafeddine R, Drieskens S, Gisle L, Tafforeau J. Methodological basics and evolution of the Belgian health interview survey 1997–2008. Archives of Public Health. 2013;71(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/0778-7367-71-24.

Berete F, Braekman E, Charafeddine R, Demarest S, Drieskens S, Gisle L, et al. Health Interview Survey Brussels, Belgium: Sciensano; 2018 [Available from: www.enquetesante.be

Goldberg DP. User’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1988.

Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003.

Braunholtz S, Davidson S, Myant K, O’Connor R. Well? What do you think?: The third national Scottish survey of public attitudes to mental health, mental wellbeing and mental health problems. Scotland: Scottish Government Edinburgh; 2007.

Van Lente E, Barry MM, Molcho M, Morgan K, Watson D, Harrington J, et al. Measuring population mental health and social well-being. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(2):421–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-011-0317-x.

Derogatis L. SCL-90-R: symptom checklist-90-R: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems; 1994.

Cox B, Van Oyen H, Cambois E, Jagger C, Le Roy S, Robine J-M, et al. The reliability of the minimum European health module. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(2):55–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-7104-y.

Janssen S, Dumont G, Fierens F, Mensink C. Spatial interpolation of air pollution measurements using CORINE land cover data. Atmos Environ. 2008;42(20):4884–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.02.043.

Lefebvre W, Degrawe B, Beckx C, Vanhulsel M, Kochan B, Bellemans T, et al. Presentation and evaluation of an integrated model chain to respond to traffic-and health-related policy questions. Environ Model Softw. 2013;40:160–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.09.003.

Lefebvre W, Vercauteren J, Schrooten L, Janssen S, Degraeuwe B, Maenhaut W, et al. Validation of the MIMOSA-AURORA-IFDM model chain for policy support: modeling concentrations of elemental carbon in Flanders. Atmos Environ. 2011;45(37):6705–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.08.033.

Maiheu B, Veldeman B, Viaene P, De Ridder K, Lauwaet D, Smeets N, et al. Identifying the best available large-scale concentration maps for air quality in Belgium. Mechelen: Flemish Institute for Technological Research (VITO); 2013.

Saenen ND, Bové H, Steuwe C, Roeffaers MB, Provost EB, Lefebvre W, et al. Children’s urinary environmental carbon load. A novel marker reflecting residential ambient air pollution exposure? American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2017;196(7):873–81. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201704-0797OC.

Gulliver J, de Hoogh K, Hansell A, Vienneau D. Development and back-extrapolation of NO2 land use regression models for historic exposure assessment in Great Britain. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(14):7804–11. https://doi.org/10.1021/es4008849.

Eeftens M, Beelen R, Fischer P, Brunekreef B, Meliefste K, Hoek G. Stability of measured and modelled spatial contrasts in NO(2) over time. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(10):765–70. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2010.061135.

Cesaroni G, Porta D, Badaloni C, Stafoggia M, Eeftens M, Meliefste K, et al. Nitrogen dioxide levels estimated from land use regression models several years apart and association with mortality in a large cohort study. Environ Health. 2012;11:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-11-48.

Ruttens D, Verleden SE, Bijnens EM, Winckelmans E, Gottlieb J, Warnecke G, et al. An association of particulate air pollution and traffic exposure with mortality after lung transplantation in Europe. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(1):1600484. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00484-2016.

Valeri L, VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods. 2013;18(2):137–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031034.

Bowe AK, Owens M, Codd MB, Lawlor BA, Glynn RW. Physical activity and mental health in an Irish population. Ir J Med Sci. 2019;188(2):625–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1863-5.

Wang S, Gao S, Li S, Feng K. Strategizing the relation between urbanization and air pollution: empirical evidence from global countries. J Clean Prod. 2020;243: 118615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118615.

Dadvand P, Rivas I, Basagana X, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Su J, De Castro PM, et al. The association between greenness and traffic-related air pollution at schools. Sci Total Environ. 2015;523:59–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.03.103.

Sass V, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Karceski S, Hajat A, Crowder K, Takeuchi D. The Effects of Air Pollution on Individual Psychological Distress. Health Place. 2017;48:72–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.09.006.

Klompmaker JO, Hoek G, Bloemsma LD, Wijga AH, van den Brink C, Brunekreef B, et al. Associations of combined exposures to surrounding green, air pollution and traffic noise on mental health. Environ Int. 2019;129:525–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.05.040.

Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25(6):494–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00310.x.

Astudillo-García CI, Rodríguez-Villamizar LA, Cortez-Lugo M, Fernández-Niño JA. Air pollution and suicide in Mexico City: a time series analysis, 2000–2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162971.

Kim Y, Myung W, Won H-H, Shim S, Jeon HJ, Choi J, et al. Association between air pollution and suicide in South Korea: a nationwide study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2): e0117929. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117929.

Yang AC, Tsai S-J, Huang NE. Decomposing the association of completed suicide with air pollution, weather, and unemployment data at different time scales. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):275–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.010.

Yamazaki S, Nitta H, Fukuhara S. Associations between exposure to ambient photochemical oxidants and the vitality or mental health domain of the health related quality of life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(2):173–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.039560.

Braithwaite I, Zhang S, Kirkbride JB, Osborn DP, Hayes JF. Air pollution (particulate matter) exposure and associations with depression, anxiety, bipolar, psychosis and suicide risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127(12): 126002. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP4595.

Buoli M, Grassi S, Caldiroli A, Carnevali GS, Mucci F, Iodice S, et al. Is there a link between air pollution and mental disorders? Environ Int. 2018;118:154–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.05.044.

Zeng Y, Lin R, Liu L, Liu Y, Li Y. Ambient air pollution exposure and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychiatry Res. 2019;276:69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.019.

Lim Y-H, Kim H, Kim JH, Bae S, Park HY, Hong Y-C. Air pollution and symptoms of depression in elderly adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(7):1023–8. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104100.

Edwards VJ, Anderson LA, Thompson WW, Deokar AJ. Mental health differences between men and women caregivers, BRFSS 2009. J Women Aging. 2017;29(5):385–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2016.1223916.

Nakao M, Yamauchi K, Mitsuma S, Omori H, Ishihara Y. Relationships between perceived health status and ambient air quality parameters in healthy Japanese: a panel study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):620. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6934-7.

Elder A, Gelein R, Silva V, Feikert T, Opanashuk L, Carter J, et al. Translocation of inhaled ultrafine manganese oxide particles to the central nervous system. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(8):1172–778. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.9030.

Calderón-Garcidueñas L, Cross JV, Franco-Lira M, Aragón-Flores M, Kavanaugh M, Torres-Jardón R, et al. Brain immune interactions and air pollution: macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF), prion cellular protein (PrP(C)), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) in cerebrospinal fluid and MIF in serum differentiate urban children exposed to severe vs. low air pollution. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2013;7:183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00183.

Calderón-Garcidueñas L, Solt AC, Henríquez-Roldán C, Torres-Jardón R, Nuse B, Herritt L, et al. Long-term air pollution exposure is associated with neuroinflammation, an altered innate immune response, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, ultrafine particulate deposition, and accumulation of amyloid beta-42 and alpha-synuclein in children and young adults. Toxicol Pathol. 2008;36(2):289–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192623307313011.

Heusinkveld HJ, Wahle T, Campbell A, Westerink RH, Tran L, Johnston H, et al. Neurodegenerative and neurological disorders by small inhaled particles. Neurotoxicology. 2016;56:94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2016.07.007.

Illum L. Transport of drugs from the nasal cavity to the central nervous system. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000;11(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-0987(00)00087-7.

Soudry Y, Lemogne C, Malinvaud D, Consoli S-M, Bonfils P. Olfactory system and emotion: common substrates. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128(1):18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2010.09.007.

Kontaris I, East BS, Wilson DA. Behavioral and neurobiological convergence of odor, mood and emotion: A review. Front Behav Neurosci. 2020;14:35. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2020.00035.

Cunningham GB, Wicker P, McCullough BP. Pollution, Health, and the Moderating Role of Physical Activity Opportunities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176272.

Dzhambov AM, Markevych I, Tilov B, Arabadzhiev Z, Stoyanov D, Gatseva P, et al. Pathways linking residential noise and air pollution to mental ill-health in young adults. Environ Res. 2018;166:458–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.031.

Biddle SJ, Ciaccioni S, Thomas G, Vergeer I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;42:146–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.011.

Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Silva ES, et al. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(7):631–48. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194.

Yu H, Yu M, Gordon SP, Zhang R. The association between ambient fine particulate air pollution and physical activity: a cohort study of university students living in Beijing. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0592-x.

Roberts JD, Voss JD, Knight B. The association of ambient air pollution and physical inactivity in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3): e90143. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090143.

Smith L, Panter J, Ogilvie D. Characteristics of the environment and physical activity in midlife: Findings from UK Biobank. Prev Med. 2019;118:150–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.10.024.

An R, Xiang X. Ambient fine particulate matter air pollution and leisure-time physical inactivity among US adults. Public Health. 2015;129(12):1637–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.017.

An R, Zhang S, Ji M, Guan C. Impact of ambient air pollution on physical activity among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Perspect Public Health. 2018;138(2):111–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913917726567.

Wen X-J, Balluz L, Mokdad A. Association between media alerts of air quality index and change of outdoor activity among adult asthma in six states, BRFSS, 2005. J Community Health. 2009;34(1):40–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9126-4.

Bourdrel T, Bind MA, Béjot Y, Morel O, Argacha JF. Cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;110(11):634–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2017.05.003.

Guan WJ, Zheng XY, Chung KF, Zhong NS. Impact of air pollution on the burden of chronic respiratory diseases in China: time for urgent action. The Lancet. 2016;388(10054):1939–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31597-5.

Cutrufello PT, Rundell KW, Smoliga JM, Stylianides GA. Inhaled whole exhaust and its effect on exercise performance and vascular function. Inhalation Toxicol. 2011;23(11):658–67. https://doi.org/10.3109/08958378.2011.604106.

Yamamoto S, Matsunaga A, Kamiya K, Miida K, Ebina Y, Hotta K, et al. Walking speed in patients with first acute myocardial infarction who participated in a supervised cardiac rehabilitation program after coronary intervention. Int Heart J. 2012;53(6):347–52. https://doi.org/10.1536/ihj.53.347.

Shekarrizfard M, Faghih-Imani A, Hatzopoulou M. An examination of population exposure to traffic related air pollution: Comparing spatially and temporally resolved estimates against long-term average exposures at the home location. Environ Res. 2016;147:435–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.02.039.

Dzhambov AM, Lercher P. Road traffic noise exposure and depression/anxiety: An updated systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(21):4134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214134.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all BHIS participants for contributing to this study.

Funding

This study was a combination of the HuBiHIS project and the NAMED project. The HuBiHIS project is financed by Sciensano (PJ) N°: 1179–101. The NAMED project was supported by the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (BELSPO), grant number: BR/175/A3/NAMED.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PH drafted the paper. PH, NS, IP and ED set up de design of the study. TN, ED, IP, HK, JvdH, SD and NS. Reviewed and commented the manuscript. All authors approved the final and submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and concent to participate

As part of the BELHES, the HuBiHIS project was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Ghent (registration number B670201834895). For the NAMED project, data linkage, relying on the secondary use of the Belgian HIS data, administrative, GIS and monitoring data did not require any approval from an Ethics committee. An application to the Sector Committee Statistics has been submitted and approved (see Decision STAT n°02/2018 from 19/01/2018). Both the NAMED and the HuBiHIS project were carried out in compliance with the European and national data protection requirements.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (n = 16,455) and the original BHIS population, eligible to complete the mental health questionnaires (n = 26,272). Supplementary table 2. The mental health indicators with their scores and uses. Supplementary table 3. Results of the main and the sensitivity analyses. Supplementary table 4. The results of physical activity associated with mental and self-rated health and air pollution. Supplementary table 5. The effects of air pollution exposure on mental and self-rated health mediated through physical activity. Supplementary table 6. Association between air pollution and depressive and generalized anxiety disorder where the outcomes are classified as tertiles. Supplementary table 7. Results of the effect modification of age. Supplementary table 8. Results of the effect modification of sex. Supplementary table 9. Results of the effect modification of socio-economic status (SES). Supplementary table 10. Overview of all literature presented in the discussion. Supplementary figure 1. Exclusion criteria. Supplementary figure 2. Directed acyclic graph (DAG) for the association between air pollution and mental and self-rated health. Red: Ancestor of exposure and outcome; Green line: causal path; Purple line: biasing path.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hautekiet, P., Saenen, N.D., Demarest, S. et al. Air pollution in association with mental and self-rated health and the mediating effect of physical activity. Environ Health 21, 29 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00839-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00839-x