Abstract

Introduction

Emergency Departments experience a significant census burst after disasters. The aim of this study is to describe patient presentations at Emergency Departments in Contra Costa County, California following chemical release incidents at an oil refinery in 2007 and 2012. Specific areas of focus include hospital and community burden with an emphasis on disease classes.

Methods

Searching 4 weeks before through 4 weeks after each event, Emergency Department abstracts identified patients living in Contra Costa County and seeking care there or in neighboring Alameda County. City and ZIP-code of residence established proximity to the refinery. This provided the following contrast groups: Event (2007, 2012), time (before, after), location (bayside, rest of county), and within bayside, warned or not warned to shelter in place. Using the Multi-Level Clinical Classification Software, we classified primary health groups recorded 4 weeks before and after the events, then summarized the data, calculated rates, and made tables, graphs, and maps to highlight findings.

Results

Number of visits meeting selection criteria totalled 105020 records. Visits increased modestly but statistically significantly after the 2007 incident. After the 2012 incident, two Emergency Departments took the brunt of the surge. Censuses increased from less than 600 a week each to respectively 5719 and 3072 the first week, with the greatest number 2 days post-event. It took 4 weeks for censuses to return to normal. The most common diagnosis groups that spiked were nervous/sensory, respiratory, circulatory, and injury. Bayside communities had statistically significant increases in residents seeking care. Specifically, visits of residents in warned communities nearest the refinery increased by a factor of 3.7 while visits of residents in other nearby un-warned communities increased by a factor of 1.5.

Conclusions

The 2012 Emergency Department census peaked in the first week and did not return to normal for 4 weeks. Diagnoses changed to reflect conditions associated with reactions to chemical exposures. Surrounding communities and nearby hospitals experienced significant emergent burdens. In addition to changes from such events in patient diagnoses and community burden, the discussion highlights the long-term implications of failures to require adequate monitoring and warning systems and failures of health planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chemical release incidents

Some events particularly stress the emergency medical services system and require executing disaster protocols and plans. This paper compares the impact of two chemical release incidents (CRI) in Richmond, California on Emergency Department (ED) utilization, population health, and community burden in 2007 and 2012.

About 5:30 PM on Monday, 06-Aug-2012, as workers attempted to repair a hydrocarbon leak, a major fire erupted at the Chevron Refinery (Refinery) in Richmond. The Refinery is located in western Contra Costa County (County) on the shores of San Francisco Bay. Five emergency responders had minor burns and received first aid [1]. Refinery CRI can result in fires, as here, or be a consequence of fires or other disasters.

As it had done after previous CRI at this Refinery, the County activated a Level 3 Community Warning System notification for Richmond, North Richmond, and San Pablo, with phone calls and sirens warning people to go indoors and shelter-in-place (SIP) [2]. Residents of warned communities live within 4–5 miles of the Refinery. Some calls notifying residents to SIP did not occur until over 4 hours after the release [3]. The County initiated the Multi-Casualty Incident Plan at “Tier 0”, denoting a major incident with no reported casualties, with alerts to hospitals, ambulance services, and other key health service personnel.

Nearby EDs were quickly overwhelmed and put on ambulance diversion. The 911 system also was overwhelmed, with ambulances responding to nearby communities and with EDs outside the immediate area experiencing surges. Due to the large number of patients seeking emergency care and calling ambulances, the County upgraded the Multi-Casualty Incident Plan to Tier 3, incident with mass casualties or potential for mass casualties [2]. Most people did not require inpatient care. However, the number of patients seeking treatment continued to surge for weeks.

The Refinery has a history of less serious CRI requiring SIP warnings: Monday 12-Apr-1989 [4], Thursday 25-Mar-1999, Thursday 31-Jan-2002, Wednesday 16-Sep-2003, and Monday 15-Jan-2007 [1]. This study focuses on the 2007 and 2012 CRI.

The County is home to other major refineries with their CRI histories before and after 2012 [1]. Two are in nearby Rodeo and two are to the immediate east of Rodeo in Martinez along the County northwest shore, in turn about 10 and 20 miles from the subject Refinery. One Rodeo refinery paid nearly a million dollars in fines since 2014 [5] and currently is seeking permits to become a major tar sands processor [6, 7]. These refineries and all towns affected by the 2012 CRI are 0–10 miles from the Hayward Fault upwelling [8, 9]. Earthquakes along the San Andreas Fault to the west and the Hayward Fault formed San Francisco Bay.

Health impact of chemical release incidents

Human health can be affected by exposure to various types of particle pollution from major industrial or natural CRI as well as by chronic exposure to power plant by-products [10, 11]. Events such as Seveso, Three Mile Island, Bhopal, Chernobyl, World Trade Center, and Fukushima [12] are examples of major CRI. Earthquakes [13,14,15], train wrecks [16, 17], hurricanes [18, 19], and wildfires [20, 21] also include CRI. Environmental contextual factors such as the nature of the incident (natural, technological, unintended, or deliberate), duration, setting, and size influence the ability of responders to care for victims [22]. A systematic review of seven decades of disaster management literature found that less than 1 in 5 of 9433 articles used a quantitative methodology to understand these events and concluded that an evidence-informed approach to disaster management is needed [23].

Smoke from chemical releases and fires contains various carcinogens and un-combusted hydrocarbons with particulate matter (PM) of various sizes. The most dangerous, called “ultrafine”, are less than 2.5 uM (micrometer). This PM size can deposit in the trachea and bronchial tree and can be inhaled as deeply as the alveoli [24].

The first acute effects of inhalation are irritation to the eyes, nose, and throat. Toxicities are principally respiratory, for example, acute asthma in children [25, 26]. Respiratory effects are rapid and occur with only a one-hour exposure [27], with the lungs usually bearing the most serious impact. The cardiovascular system is also involved, either secondary to pulmonary damage or directly [28]. For example, during the brief time cleaning up after a fire without breathing protection, firefighters have a significant decrease in pulmonary function with evidence of increased alveolar capillary membrane permeability [29].

Smoke inhalation produces long term pathology that includes worsening of asthma and cardiovascular effects such as stroke and cardiac disease [21, 30, 31]. People with existing heart or lung disease, people with diabetes, older adults, children, and people of lower socio-economic status have greater risk of particle pollution health effects [8, 9, 32].

Chronically exposed to PM from various refineries ringing its shores and crosshatched with several highly-trafficked freeways, County residents of all age groups have higher rates of asthma-related ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths as compared to Californians state-wide [33], with west County residents having extremely high rates [34]. The west County region has six times more diesel air pollution per square mile annually (more than 5 tons) than the County as a whole (0.8 tons), and 40 times more than California state-wide (0.1 ton) [35].

Importance of adequate air monitoring

In a large industrial fire, smoke and its associated chemicals may affect residents in both nearby and upwind or downwind neighborhoods. Unfortunately, no air monitoring was done for the 2007 event, and no reliable air quality data exists for the 2012 event. Monitoring stations were not located near affected neighborhoods, and monitoring did not begin until after emergency responders extinguished the fire [36].

Fence-line, community, and mobile monitoring are standard air monitoring methods, and each serves a distinct purpose. Fence-line monitoring primarily identifies non-routine emissions during normal operation [37]. Community monitoring provides data to develop spatial gradients of chronic exposure [38]. Mobile monitoring supplements on-going monitoring during incidents [39]. Time resolution for each method will differ, with fence-line on the order of hours, and mobile only under special circumstances.

The first monitoring after the 2012 fire was by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District’s (BAAQMD) permanent monitors, which would be classed as community monitors. Of the 40-monitor network, only five were in the western County where all refineries are located. BAAQMD monitors sample for hydrogen sulphide, elemental carbon, ozone, sulfur dioxide, and PM 10. The only reliable PM monitor, 2 miles east of the Refinery, did not sample until after the fire ended. About 2 hours after the fire ended, BAAQMD also used ambient air canisters at eight individual locations, analysing 23 compounds including benzene, toluene, and ethanol. Again, no BAAQMD monitoring assessed PM or un-combusted hydrocarbons.

The evening of the 2012 CRI, the Refinery took 17 direct-reading samples for hydrogen sulphide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide in Richmond, and collected 19 Tedlar bag samples in downwind communities to test for hydrocarbon and sulfur compounds. Over the next 2 days, the Refinery did more follow-up monitoring for hydrogen sulphide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide. However, as here, refinery fires typically are relatively short events, and sampling after the event is not helpful to show community impacts. No sampling tested for heavier hydrocarbons that could indicate the severity of pollution from a refinery fire.

If available, two other methods can measure exposure: analysis of photos of the event and meteorological analysis. Available photos show fire and smoke from four distinct locations within the Refinery boundaries, with thick, black particulate matter spreading across a large geographic area and into the atmosphere. Exact times and locations for photos were not standard, and the fire burned well past sunset. Thus, it was not possible to conclude anything but that dense black smoke was consistent with PM presence. Meteorological analysis was inconsistent because of placement of weather stations, two on a pier about 2 km southwest of the fire separated by a 300 m high ridge, and another about 2 km northeast of the fire. Such facilities may experience very different wind patterns [33].

Materials and methods

Overall design

To assess the impact of the Refinery CRI on ED utilization and population health, we used confidential ED data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) [40] to compare visit rates 4 weeks before and 4 weeks after the 2007 and 2012 Refinery CRI by place of residence in the County. For both events, the County issued SIP warnings for the same communities. The numerator of each rate is a count of records within various categories, and the denominator is total population. Secondary analysis involved graphing count data and mapping rates.

Hospital data

We began this study using confidential ED and Patient Discharge (PD) data previously prepared for longitudinal research [41]. These files contain medical summaries of all patient visits to EDs or admissions to hospitals licensed by the State of California. Patients admitted to inpatient care through the ED are reported in the PD files.

ED data are not available before 2005, so we focused on the 15-Jan-2007 and 06-Aug-2012 events. Following up on the Wettstein et al. methodology [18], we explored using both ED and PD data. Unlike Wettstein, studying the health impact of forest fires, we found no PD surge overall or for inpatient admissions through the ED. Given this, we dropped PD data.

Variables used include patient’s birthdate, sex, ZIP-code and county of residence, ED visit date, and principal diagnosis (PDX) classified based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Preliminarily selected records met the following basic criteria: sex, birthdate, and PDX present, resident of the County and seeking care in the County or neighboring Alameda County in the period 4 weeks before through 4 weeks after the 2007 or 2012 CRI. These criteria found 105020 ED visits.

To classify conditions, we used Level 1 (Body System, DXCH) and Level 2 (Disease Condition, DXCL) of the Multi-Level Clinical Classification Software (CCS) developed by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [42]. Affected body systems (DXCH) and conditions under body systems (DXCL) were identified by searching the PDX field. To identify conditions contributing to high frequency DXCH, we selected DXCL diagnosed for 500 or more patients from the BAY region in the 8-week period around the 2012 event. See Additional file 1 for descriptions of groupers to select records and classify conditions.

Contrast groups

This work uses four contrast groups based on events, time, place, and warning. Selected events occurred in 2007 and 2012 in Richmond, California. Both events occurred on a Monday. We calculated the study frame as the period 4 weeks before and 4 weeks after the day of each event, with event day and week assigned the value zero (0). This created a 56-day interval to assess ED utilization with two 4-week windows of equal length before (days − 28- to − 1, weeks − 4 to − 1) and after (days 0–27, weeks 0 to 3) the 2007 and 2012 events. We also made a categorical time variable with two groups: before and after.

The Refinery and affected cities are geographically at the County’s western boundary along the shore of San Francisco Bay (BAY, West County) in northern California. A low mountain ridge to the east separates the primary study area BAY from the rest of county (ROC). This ridge is the upwelling of the Hayward Fault [8]. We used ZIP-code (ZIP) of patient residence to assign city, assigned cities to BAY or ROC, and within BAY, flagged ZIPS warned to SIP.

Two BAY communities received SIP warnings: Richmond (which includes North Richmond, ZIPs 94801, 94804, 94805) and San Pablo (94806). Most residents in these ZIPs live less than 4 miles from the Refinery. Other BAY communities, about 4 to 10 miles from the Refinery, did not receive SIP warnings: Rodeo (94572), Hercules (94547), Pinole (94564), El Sobrante (94803), and El Cerrito (94530). This created comparison groups based on events (2007, 2012), time (before, after), place (BAY, ROC), and within BAY, SIP warning (warned/not warned).

Population denominator

We maintain a set of longitudinal (1970 forward) files with California population estimates by sex, age, and race/ethnicity, with ZIP-code level estimates from 1989 forward [43]. For this study, we extracted the 2007 and 2012 County ZIP-level estimates, and assigned ZIPs to BAY or ROC and warned or not warned, then summarized the data to obtain total population.

Statistical tests

We summarized the diagnosis-classified file by 2-level event (2007, 2012), place (ZIP, BAY, ROC), time (before, after), and SIP warning status (warned, not warned), then merged the summary with the population denominator file. To calculate rates per 1000 (1 K) population, the numerator was the count of ED visits within the various categories. The denominator was the population estimate for the geographical area in the given year. To calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for rates, we used the Wilson Score method with continuity correction [44].

To describe difference between rates, we calculated the relative risk (RR) or risk ratio, selecting the usually higher rate divided by the usually lower rate, yielding RR values usually greater than 1.0. In the context of this study, the usually higher rates were After-CRI versus Before-CRI, BAY versus ROC, and warned ZIPs nearest the Refinery versus not warned. Upper (UCL) and lower (LCL) confidence limits for the RR were calculated using the method described for SAS® Proc Freq, “Relative Risk Estimates”, “Cohort Studies” [45]. Two-tailed p-values corresponding to the CL were obtained by setting the formula for the LCL equal to 1.0, solving for the Z-score, and obtaining the corresponding probability from the normal distribution.

The term “significant” used in this study combines both statistical and clinical criteria, specifically a LCL of 1.05 or more, and p-value of .01 or less. The purpose is to minimize trivial findings [46, 47]. In tables, we show decimals as needed to document CL width. In addition, we bold column RR values that are 1.10 or more and meet the above criterion for “significant”. In the text, we report significant rates without the CL. We also developed graphs to show the changing surge by time, grouping cities by whether residents were or were not told to SIP.

All programming was in SAS 9.4. Programs to prepare data and calculate statistics used SAS macros developed by our group. SAS formats [48] and macros [49] are available on our website. Programs specific to the work reported here are available on request. The map was made using ArcMap 10.6. Human subjects protocol restrictions do not allow data sharing. However, researchers with the same files and our programs would be able to replicate our results.

Results

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics for the County and the census of ED visits by area and event year. The County reflects the diverse population of the larger San Francisco Bay Area. With a County population of about 1 million, about 27% live in West County (BAY).

ED caseloads are unpredictable and, by law, ED may not choose patients they accept or limit the number of patients seen. With modest changes in countywide total population, BAY had an absolute increase of 14997 ED visits (128.6%) in 2012 compared with an absolute increase of 7053 for ROC (23.6%), with huge increases in all age groups in BAY relative to ROC. For example, with about one-quarter of the County population, BAY visits for age 15–44 increased by 6550 (129.6%) in 2012 versus an increase of 2813 (22.4%) for ROC.

This provides a longitudinal overview of ED census changes, but does not give insight into how census changed with CRI. Figure 1a shows the average number of visits over the 8-week study period for the two EDs taking most of the burst from the 2012 CRI. Before the CRI, each ED had about 80 visits daily. The week of the CRI, average visits per day rose respectively to 817 and 439. It took about 4 weeks to return to pre-CRI levels. The 2012 CRI occurred at 5:30 PM on Monday Day 0. By midnight, when the census day changes and 6.5 h after the fire began, Fig. 1b indicates the Monday census more than doubled in ED1 (N = 231) and increased about 70% in ED2 (N = 149). In Week 0, both EDs surged for several days, with census still above average at end of week and from Fig. 1a, high through the next several weeks.

Table 2 identifies major body systems with 1000 or more cases and with number of cases at least 10% greater after than before the CRI. Comparing before and after, the table shows the number of patients with the diagnosis, rates adjusted per 1 K population with associated LCL and UCL, and symbols indicating the type of statistically significant comparison. Consistent with reports summarized earlier that identified the BAY as having chronic severe air quality problems and more illness, here we see that BAY had higher illness rates than ROC for most identified body systems before the CRI in both 2007 and 2012.

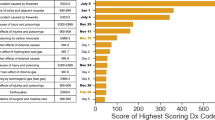

Nervous system/sensory system conditions that increased significantly post-CRI were migraine headaches (RR = 4.3), eye infections (RR = 6.3), other eye conditions (RR = 11.1), and dizziness (RR = 1.7). Within the circulatory system, chest pain (RR = 1.5) was the only diagnosis group with enough cases that increased post-CRI. Respiratory conditions showing an increase were asthma (RR = 2.9), upper respiratory infections (laryngitis, pharyngitis, sinusitis) (RR = 2.2), and other upper (RR = 6.8) and lower (RR = 4.5) respiratory conditions. Under injury/poisoning, non-medical poisoning (RR = 51.9) was the common factor. See Additional file 2 for details.

Figure 2 examines changes in the number of patients by affected body system, comparing week days Monday through Sunday the week before and after the 2012 CRI. After the event, the number of patients with given diagnoses exploded. For example, consider circulatory conditions (Fig. 2b), in this case primarily chest pain. On Monday (Day 0), number of patients with circulatory conditions increased 4-fold from 11 (the previous Monday) to 43 and peaked at 83 on Thursday, almost a 10-fold increase over the previous Thursday. With post-CRI increases in the high 600 s, nervous system/sensory and respiratory systems were most affected. We also see that different conditions peak at different times following a CRI like this.

Now we turn to the community burden of these CRI. Table 3 shows -- by year, warning status, and location -- the number of ED visits in the 4 weeks before and after each CRI. The Refinery is in ZIP 94801. Overall, the 2007 CRI had a significant but modest impact near the Refinery (primarily ZIPS 94804 and 94806) (RR = 1.12), over the rest of the BAY region (RR = 1.12), and also in ROC (1.11). Among the warned zips, 94801 (where the Refinery is located), and 94805 showed no increase in ED visits (RR = 1.02 and 0.98) in spite of being warned to SIP. The 2012 CRI significantly affected all BAY communities, but not ROC.

Figure 3 is a map of the affected areas, with the west and northwest border on San Francisco Bay, with ROC not shown to the east and northeast, and Alameda County to the south. Locations of the subject Refinery and the two EDs in this area are identified, as are other refineries in Rodeo and Martinez. The subject Refinery and other refineries have had CRI since 2012 [1]. In the 2007 and 2012 CRI, officials issued SIP warnings (solid boundaries) in Richmond (ZIP 94801 (includes North Richmond), 94804, 94805), and San Pablo (ZIP 94806) but did not warn other Bayside towns (dashed boundaries). The Hayward Fault upwelling is along the eastern boundaries of unwarned ZIPs. The map repeats the ZIP-level 2012 RR from Table 3.

Figure 4 shows ED visits by residents of warned towns for the 4 weeks before and after the 2007 and 2012 CRI (Table 3, RR range. 2.8–4.8 in 2012). In Week 0, the absolute number of visits increased 7- to 10-fold and, depending on area, did not return to normal until Week 3.

Figure 5 turns to BAY communities not warned to SIP. In the 2012 CRI, ED visits increased significantly (Table 3, RR range 1.33–1.69), and number of weeks to return to pre-CRI numbers varied by town. To simplify the figure, we do not show Pinole.

Discussion

Consistent with the review article highlighting the paucity of population-based quantitative studies [20], the only approximately comparable CRI report we found used California ED and PD data to focus on forest fires. Wettstein and colleagues [18] reported the expected increases in respiratory conditions but also identified that cardiovascular events were prominent in the wild fire exposed population. We did not find the increase in heart attacks that Wettstein reported. This may be due to the magnitude of stress experienced by people fleeing enormous wildfires with attendant loss of treasured personal belongings, pets and farm animals, homes, and even entire communities.

Over 2000 residents of communities warned to SIP during the 2012 CRI filed a lawsuit against the Refinery [50]. In 2017, the court ordered physical examinations of 40 randomly selected plaintiffs, with medical histories and medical records review. The court confined the physicals to assessing head, eyes, ears, nose, throat, lungs, heart, and deep tendon reflex, and limited the report to the number seeking urgent medical care, those reporting wheezing within several days, and those whose physicians reported worsening of existing asthma or introduction of more powerful asthma medications within 4 weeks. As confirmed by health interviews conducted 5 years after the 2012 CRI, most conditions were transient, frightening, but not life threatening. However, half (N = 20) had no respiratory symptoms before the 2012 event and of those, 5 remained symptomatic. Of 20 plaintiffs with respiratory conditions before 2012, symptoms returned to pre-event levels for 5 and were worse for 15. Thus, about half of plaintiffs had new or worsened chronic respiratory conditions. This is consistent with reports of children’s respiratory outcomes after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake that also affected this community [11].

The BAAQMD air monitoring network did not capture localized impacts from short duration incidents like the 2012 Refinery fire [33]. Meaningful monitoring requires routine analysis of dozens of compounds, more than the 23 that BAAQMD sampled after the 2012 event. No monitors in the Refinery’s vicinity sampled PM 2.5, the cause of acute health effects. In this short-term, high-intensity event emissions impacted areas without air monitors. An abundance of well-placed monitors is needed to provide an accurate picture of the impacts of CRI events such as a refinery fire. This did not exist in 2012. Both a denser permanent network in areas near the refineries and greater capacity for mobile short-term monitoring are advised.

With no functioning or properly placed monitors, no air quality reports exist to determine the levels or types of chemicals released. In such circumstances, alternative resources may help to understand the health impact. We turned to ED records to study changes in presenting diseases as an alternative. This approach will not identify chemicals released but will identify types of illness to expect from a similar CRI involving petroleum by-products. It may also help EDs plan their responses for future CRI.

In both the 2007 and 2012 event, the County issued SIP warnings to the same communities. Both times, the same ineffective monitoring systems were in place. The 2007 event caused a modest but significant increase in ED utilization that the 2012 event dwarfed, and both events increased rates in the same body systems (Table 2). From this we conclude that both CRI released similar toxics, with releases of different magnitudes.

Initial reports after the 2012 CRI ascribed the increase in ED utilization to the notion that residents were nervous because of the SIP. However, communities that did not receive SIP warnings in either 2007 or 2012 experienced statistically significant increases in ED utilization (Table 3). During the 2007 CRI, the four nearby ZIPs warned to SIP showed divergent results, with the two northerly ones showing significant increases (RR = 1.18 and 1.23), while the two southerly ones showed no increase (RR = 1.02 and 0.98). This is consistent with a more northerly direction of the 2007 CRI plume, and is inconsistent with the hypothesis that warning the public to SIP, by itself, caused an increase in ED visits.

From this we conclude that SIP warning did not cause the surge, but rather the unmeasured magnitude of the CRI events drove thousands of people to seek emergency care. This puts into focus the public health consequences of officials making decisions that are not data-driven [14]. It also highlights the family and community burden of such events in terms of losing work days, scrambling to find child care, and traveling long distances with sick family members to obtain care amidst the vagaries of Bay Area traffic.

In the context of the relatively mild uptick in ED utilization from the 2007 event, state, regional, county, and local officials did not require the Refinery (and other County refineries) to properly maintain and appropriately place monitoring equipment and to report routine chemical release data. As of the writing of this paper, we do not know if any government agency has reported the full extent of emissions from the 2012 Refinery incident [51]. Although BAAQMD recommended adding “mobile monitoring capabilities to better assess incidents in the future [52]”, we did not find any reports that they have done so.

The subject Refinery is one of a number ringing the County’s west and north borders (Fig. 3), and one of the more risky from the point of prevailing winds blowing from the shores of San Francisco Bay. Since the 2012 event, area refineries continue to have CRI [1], and a Rodeo refinery currently is seeking approval to become a major processor of tar sand oil in the United States [6, 7, 53]. We strongly recommend that the County review and consider expanding its SIP warning areas.

The enormous 2012 census increase in only two small EDs was caused both by the magnitude of the unmeasured emissions and also by the paucity of ED and general acute care facilities in this highly populated urban area. The BAY region has only 50 in-patient beds [54, 55]. From the Refinery, it is a 45-min drive to the next nearest County inpatient hospital, and a 30-min drive to the nearest Alameda County hospital, subject to conditions on the most heavily trafficked roads in Northern California.

In the 1970s, California passed comprehensive legislation to create a framework to control hospital costs yet protect patient safety. The legislation required an inventory of health facilities, planning processes including regional Health Service Areas, local Health Facilities Planning Areas, and Certificates of Need to justify closures or service expansions, development of data systems to monitor utilization, costs, and expenditures and safety-related policies to monitor hospital structures, processes of care, and patient care [56, 57].

In 1987, responding to intense hospital industry lobbying, the legislature suspended the Certificate of Need and related planning activities and permitted hospitals to close or consolidate without state review. Unlike states that kept Federal planning requirements in place, California deregulated its healthcare system, finding it “indispensable that providers of health care be free to engage in voluntary, cooperative efforts with consumers, government, or other providers of health care to fulfill the purposes of the health planning laws [58]”. In a series of studies, Remy and colleagues documented the consequences of deregulation for access to care for California’s children, pregnant women, and the mentally ill [59,60,61].

The County population grew 45% from 803732 in 1990 [62] to 1165190 in 2019 [63]. Between the 1987 deregulation and the 2012 CRI, one hospital in the County closed, three hospitals closed their ED, and the publicly-owned district hospital housing ED2 closed its inpatient facility with California’s only burn unit north of San Francisco. Two years after the 2012 CRI, ED2 closed. Today, one hospital with ED1 and 50 inpatient beds serves one-quarter of the County population in the BAY region. Bounded on the east by the upwelling of the Hayward Fault, the region is lower income and has poorer health due at least in part to ongoing refinery-derived air pollution [30, 31]. By contrast, 9 hospitals with 6 EDs and about 1800 inpatient beds serve about three-quarters of the County population living in higher-income, lower-risk communities. Given population growth and hospital changes, the regional health infrastructure will be increasingly challenged to respond to future CRI or other major disasters.

Conclusions

It is hard to imagine conditions faced by medical staff in two small Emergency Departments typically treating about 80 people over a 24-h day, but they managed to provide urgent care to thousands of people following a major industrial accident in 2012. Court-ordered examinations of randomly-selected plaintiffs showed that many patients emerged with worsened chronic health conditions. The importance of adequate air monitoring and emergency warning systems is highlighted by their absence when these events occurred. Warnings did not cause people to seek care. CRI emissions caused people to seek care. In this context, the data strongly suggests that more areas need to receive SIP warnings. In 2014, Emergency Department capacity in the area was reduced by half. The County’s growing population combined with its decreased and unevenly distributed hospital capacity raises concerns about the ability to provide adequate care during future events of similar or worse magnitude.

Abbreviations

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- BAAQMD:

-

Bay Area Air Quality Management District

- CCS:

-

Multi-Level Clinical Classification Software

- CI:

-

95% confidence interval

- CRI:

-

Chemical release incident

- DXCH:

-

CCS Body-system level diagnosis classification

- DXCL:

-

CCS Diagnosis group class within body system

- ED:

-

Emergency Department

- LCL:

-

Lower confidence limit

- PD:

-

Patient discharge data

- PDX:

-

Principal diagnosis

- RR:

-

Relative risk or risk ratio

- SIP:

-

Shelter in place

- UCL:

-

Upper confidence limit

References

Contra Costa Health Services: Major Accidents at Chemical/Refinery Plants in Contra Costa County. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: https://cchealth.org/hazmat/accident-history.php.

Contra Costa Health Services: Chevron Richmond Refinery Fire of August 6, 2012 After Action Report Based on Medical/Health Debriefing Conducted September 10, 2012. Publishing Date: 12/06/2012. Last accessed 18 Jan 2019 at: https://cchealth.org/ems/pdf/Chevron-Richmond-Refinery-Fire-AAR-2012-0806.pdf

U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board: Final Investigation Report No. 2012–03-I-CA Chevron Richmond Refinery Pipe Rupture and Fire. January 2015. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: https://www.csb.gov/file.aspx? DocumentId=5917.

Lee P. Chevron fined $877,000 for refinery fire. Los Angeles Times, 1989. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: http://articles.latimes.com/1989-09-27/business/fi-266_1_chevron-fire.

Dineen JK. Rodeo refinery to pay nearly $800,000 over pollution violations. San Francisco Chronicle, 2016. Earlier $200,000 fine reported in article. Last access 19-Mar-2019 at https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Rodeo-refinery-to-pay-nearly-800-000-over-9116870.php.

Krogh, M. Canada’s tar sands pipeline plan threatens Bay Area. Mercury news, 2018, last access 21 Mar 2019 at: https://www.mercurynews.com/2018/10/05/opinion-canadas-tar-sands-pipeline-plan-threatens-bay-area/.

Phillips 66 Co.’s San Francisco Refinery Tar Sands Oil Expansion in Rodeo, CA. Last access 19 Mar 2019 at: http://www.cbecal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/San-Francisco-Refinery-Tar-Sands-Expansion-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

Hudnut KW, Wein AM, Cox DA, Porter KA, Johnson LA, Perry SC, Bruce JL, LaPointe D. The HayWired earthquake scenario—we can outsmart disaster: U.S. Geological Survey fact sheet 2018–3016; 2018. p. 6. https://doi.org/10.3133/fs20183016

Brinklow A. Here’s what to expect when the Big One hits the Hayward Fault. 2018. SF Curbed, Last access 23 Mar 2019 at: https://sf.curbed.com/2018/4/19/17256362/ hayward-fault-usgs-oakland-earthquake.

Liu NM, Grigg J. Diesel, children and respiratory disease. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2018;2(1):e000210. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000210 eCollection 2018.

Casey JA, Karasek D, Ogburn EL, Goin DE, Dang K, Braveman PA, Morello-Frosch R. Coal and oil power plant retirements in California associated with reduced preterm birth among populations nearby. Am J Epidemiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy110 [Epub ahead of print].

Lucchini RG, Hashim D, Acquilla S, Basanets A, Bertazzi PA, Bushmanov A, Crane M, Harrison DJ, Holden W, Landrigan PJ, Luft BJ, Mocarelli P, Mazitova N, Melius J, Moline JM, Mori K, Prezant D, Reibman J, Reissman DB, Stazharau A, Takahashi K, Udasin IG, Todd AC. A comparative assessment of major international disasters: the need for exposure assessment, systematic emergency preparedness, and lifetime health care. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3939-3.

Boyce WT, Chesterman EA, Martin N, Folkman S, Cohen F, Wara D. Immunologic changes occurring at kindergarten entry predict respiratory illnesses after the Loma Prieta earthquake. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14(5):296–303 PMID 8254059.

Wu CL, Lan FY, Chen BL, Chang RH, Chang WH, Pan ST, Fang PH, Lu CH, Lin CH. Respiratory symptoms among search and rescue workers who responded to the 2016 Taiwan earthquake. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(9):639–46. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2018-105027 Epub 2018 Jul 10.

Barbieri A, Melegari G, Lob V, Mazzali L, D'Amelio L, Giovannoni A, Giuliani E. Response by twin Italian hub hospitals in a double seismic event: a retrospective observational investigation. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(3):353–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1394406 Epub 2018 Jan 18.

Hsu EB, Grabowski JG, Chotani RA, Winslow JA, Alves DW, VanRooyen MJ. Effects on local emergency departments of large-scale urban chemical fire with hazardous materials spill. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2002;17(4):196–201.

Forsberg R, Björnstig U. One hundred years of railway disasters and recent trends. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26(5):367–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X1100639X Epub 2011 Sep 21.

Peters MN, Moscona JC, Katz MJ, Deandrade KB, Quevedo HC, Tiwari S, Burchett AR, Turnage TA, Singh KY, Fomunung EN, Srivastav S, Delafontaine P, Irimpen AM. Natural disasters and myocardial infarction: the six years after hurricane Katrina. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(4):472–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.12.013 Epub 2014 Mar 18.

Kishore N, Marqués D, Mahmud A, Kiang MV, Rodriguez I, Fuller A, Ebner P, Sorensen C, Racy F, Lemery J, Maas L, Leaning J, Irizarry RA, Balsari S, Buckee CO. Mortality in Puerto Rico after hurricane Maria. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):162–70. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1803972 Epub 2018 May 29.

Shusterman D, Kaplan JZ, Canabarro C. Immediate health effects of an urban wildfire. West J Med. 1993;158(2):133–8 PMID: 8434462. PMCID: PMC1021964.

Wettstein ZS, Hoshiko S, Fahimi J, Harrison RJ, Cascio WE, Rappold AG. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular emergency department visits associated with wildfire smoke exposure in California in 2015. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7(8). doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.007492.

Culley JM, Effken JA. Development and validation of a mass casualty conceptual model. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42(1):66–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01320.x.

Smith EC, Burkle FM, Aitken P, Leggatt P. Seven decades of disasters: a systematic review of the literature. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2018;33(4):418–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X18000638.

Heyder J. Deposition of inhaled particles in the human respiratory tract and consequences for regional targeting in respiratory drug delivery. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1(4):315–20. PMID: 16113452. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.200409-046TA.

Anderson HR, Gupta R, Kapetanakis V, Asher MI, Clayton T, Robertson CF, Strachan DP. ISAAC steering committee. International correlations between indicators of prevalence, hospital admissions and mortality for asthma in children. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(3):573–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyn039 Epub 2008 Mar 13.

Li Q, Yi Q, Tang L, Luo S, Tang Y, Zhang G, Luo Z. Influence of ultrafine particle exposure on asthma exacerbation in children: a meta-analysis. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(4):412–20. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450119666180829114252.

Salvi S, Blomberg A, Rudell B, Kelly F, Sandström T, Holgate ST, Frew A. Acute inflammatory responses in the airways and peripheral blood after short-term exposure to diesel exhaust in healthy human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(3):702–9.

Kato T, Yashiro T, Murata Y, Herbert DC, Oshikawa K, Bando M, Ohno S, Sugiyama Y. Evidence that exogenous substances can be phagocytized by alveolar epithelial cells and transported into blood capillaries. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311(1):47–51 Epub 2002 Nov 22.

Burgess JL, Nanson CJ, Bolstad-Johnson DM, Gerkin R, Hysong TA, Lantz RC, Sherrill DL, Crutchfield CD, Quan SF, Bernard AM, Witten ML. Adverse respiratory effects following overhaul in firefighters. J Occup Environ Med. 2001;43(5):467–73.

Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, Mittleman M, Samet J, Smith SC Jr, Tager I. Expert panel on population and prevention science of the American Heart Association. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109(21):2655–71.

Baldacci S, Maio S, Cerrai S, Sarno G, Baïz N, Simoni M, Annesi-Maesano I, Viegi G, Study HEALS. Allergy and asthma: effects of the exposure to particulate matter and biological allergens. Respir Med. 2015;109(9):1089–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2015.05.017 Epub 2015 May 22.

US Environmental Protection Agency. Particle Pollution and Your Patients’ Health. Why is particle pollution a respiratory health concern? Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: https://www.epa.gov/particle-pollution-and-your-patients-health/health-effects-pm-patients-lung-disease#intro

Contra Costa County Asthma Profile. Modified on: Thursday, 01 September 2016. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/DEODC/EHIB/CPE/CDPH%20Document%20Library/County%20profiles/ContraCosta2016profile.pdf.

Contra Costa Asthma Coalition. Report to the community on asthma. 2008. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: http://www.rampasthma.org/pdfs/CAFA_Contra_Costa.pdf

California Air Resources Board. Air Quality and Land Use Handbook: A Community Health Perspective. 2005. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: https://www.arb.ca.gov/ch/landuse.htm

Bay Area Air Quality Management District: Air District lab completes PM sample analysis from Chevron fire, BAAQMD News. 2012. Last access 18-Jan-2019 at: http://www.baaqmd.gov/about-air-quality/incidents-and-advisories/chevron-refinery-fire.

Thoma ED, Miller MC, Chung KC, Parsons NL, Shine BC. Facility fence-line monitoring using passive samplers. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2011;61(8):834–42.

Llavador Colomer F, Espinós Morató H, Mantilla Iglesias E. Estimation of hydrogen sulfide emission rates at several wastewater treatment plants through experimental concentration measurements and dispersion modeling. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2012;62(7):758–66.

Stewart-Evans J, Hall L, Czerczak S, Manley K, Dobney A, Hoffer S, Pałaszewska-Tkacz A, Jankowska A. Assessing and improving cross-border chemical incident preparedness and response across Europe. Environ Int. 2014;72:30–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2014.03.012 Epub 2014 Apr 24.

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, (OSHPD). Request Data. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: https://oshpd.ca.gov/data-and-reports/request-data/tools-resources/#IPA

Remy LL, Clay T. Methods for maintaining longitudinal population health studies: Preparing master files. Family Health Outcomes Project, University of California, San Francisco. Available at: https://fhop.ucsf.edu/data-management-methods.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Palmer L. Clinical classifications software (CCS), 2014. US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

Remy L, Clay T. Methods for maintaining longitudinal population health studies. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco, Family Health Outcomes Project; 2017. Available at: http://fhop.ucsf.edu/data-management-methods.

Newcomb RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):857–72.

SAS/STAT(R) 9.3 User’s Guide. The FREQ Procedure. Last access 19 Mar 2019 at: https://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63962/HTML/default/viewer.htm#statug_freq_a0000000565.htm

Schober P, Bossers SM, Schwarte LA. Statistical significance versus clinical importance of observed effect sizes: what do P values and confidence intervals really represent? Anesth Analg. 2018;126(3):1068–72. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002798.

Ioannidis JPA. The proposal to lower P value thresholds to .005. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1429–30. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.1536.

See FORMATS.ZIP at http://fhop.ucsf.edu/data-management-methods

See TOOLS.ZIP at http://fhop.ucsf.edu/data-management-methods

In Re: Chevron Refinery Fire Cases. Case number MSC12-01841, filed 15-Aug-2012. Superior Court of California, County of Alameda. Last access 18 Jan 2018 at: http://icms.cc-courts.org/tellme/tellme/casenumbersearch.asp?language=ENGLISH&casefiled=&knowcasenumber=Y.

California Air Resources Board. See Chevron Products Company - Richmond Refinery, 94802, 2008-2016. Last access 22 Mar 2019 and data downloaded 17-Feb-2018 at: https://www.arb.ca.gov/ei/tools/pollution_map/

BAAQMD. Air District lab completes PM sample analysis from Chevron fire. 2012. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: http://www.baaqmd.gov/~/media/files/communications-and-outreach/publications/news-releases/2012/2012-033-pmdatamediarelease-82312.pdf

Bacher D. Town hall exposes risks of rodeo refinery expansion to local health, climate and S.F. Bay. 2019. Last access 21 Mar 2019 at: https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/03/09/18821781.php.

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, (OSHPD) Hospital Annual Financial and Utilization data. Last access 18 Jan 2019 at: https://data.chhs.ca.gov/dataset/hospital-annual-financial-disclosure-report-complete-data-set

Remy L, Clay T. Managing longitudinal research studies: annual hospital disclosure report. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco, Family Health Outcomes Project. Available at: http://fhop.ucsf.edu/data-management-methods

California health and Safety code sections 127125–127300, 129450–129460, 129475–129535.

Title 22, Social Security, Division 5. Licensing and Certification of Health Facilities, Home Health Agencies, Clinics, and Referral Agencies.

California Health and Safety Code Section, 127140(a).

Oliva G, Remy L, Clay T. The impact of changing public policy on California's hospital infrastructure and on children's hospital outcomes - 1983-2000: For the California Policy Research Center, University of California Office of the President; 2005. Available at: http://fhop.ucsf.edu/fhop-publications-hospitalizations-trends-and-outcomes.

Remy L, Oliva G, Clay T. Maternal morbidity and outcomes including mortality, California 2001–2006. Family health outcomes project. San Francisco: University of California; 2008. Available at: http://fhop.ucsf.edu/fhop-publications-hospitalizations-trends-and-outcomes

Remy L, Oliva G. Structural capacity to treat mental illness 1995–2004. In: For the Maternal, Adolescent, and Child Health Branch, California Department of Health Services. Family Health Outcomes Project: University of California San Francisco; 2008. Available at: http://fhop.ucsf.edu/fhop-publications-hospitalizations-trends-and-outcomes.

State of California, Department of Finance. Race/Hispanics Population with Age and Gender Detail, 2000–2010. Sacramento; 2012. (Revised to include decimal detail). Last access 09 Jan 2019 at: http://www.dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/Estimates/Race-Ethnic/2000-2010/Intercensal_2000-2010_DBInput_csv.zip.

State of California, Department of Finance. Report P-3: State and County Population Projections by Race/Ethnicity, Detailed Age, and Gender, 2010–2060. Sacramento; 2016. Updated 11 Jan 2018. Last access 28 Mar 2019 at: http://www.dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/Projections/P3_Complete.csv.zip.

Acknowledgements

This work was covered by the following human subjects protocols: IRB 10-05122, Reference 059960, Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco; Project 13-02-1077, Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, State of California Health and Human Services Agency; and Request 2140325-01, Healthcare Information Research Center, Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, State of California Health and Human Services Agency.

We thank Alison Guse and Shauna Burr of SWAPE for making the map (Fig. 3). Al Levin, MD JD, helped with the literature search and read every draft.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LR conceived the study, did all data analysis, and prepared figures and tables. TC advised on design and methodology, wrote all SAS macros, provided statistical consultation, and helped interpret statistical results. LR, VB, and PS contributed to the first draft of the Background section. LR and TC co-wrote the methods section. LR wrote the first draft of the Results section. VB and LR wrote the first draft of the Discussion section. VB performed the history and physical examination on 40 plaintiffs. All authors read, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

List of AHRQ/CCS diagnosis groupers. (PDF 31 kb)

Additional file 2:

Short list of diagnosis groups within body system. (PDF 45 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Remy, L.L., Clay, T., Byers, V. et al. Hospital, health, and community burden after oil refinery fires, Richmond, California 2007 and 2012. Environ Health 18, 48 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0484-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0484-4