Abstract

Background

Ensuring access to essential quality health services and reducing financial hardship for all individuals regardless of their ability to pay are the main goals of universal health coverage. Various health insurance schemes have been recently implemented in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to achieve both of these objectives. We systematically reviewed all available literature to assess the extent to which current health insurance schemes truly reach the poor and underserved populations in LMICs.

Methods

In the systematic review, we searched on PubMed, Web of Science, EconLit and Google Scholar to identify eligible studies which captured health insurance enrollment information in LMICs from 2010 up to September 2019. Two authors independently selected studies, extracted data, and appraised included studies. The primary outcome of interest was health insurance enrollment of the most vulnerable populations relative to enrollment of the best-off subgroups. We classified households both with respect to their highest educational attainment and their relative wealth and used random-effects meta-analysis to estimate average enrollment gaps.

Results

48 studies from 17 countries met the inclusion criteria. The average enrollment rate into health insurance schemes for vulnerable populations was 36% with an inter-quartile range of 26%. On average, across countries, households from the wealthiest subgroup had 61% higher odds (95% CI: 1.49 to 1.73) of insurance enrollment than households in the poorest group in the same country. Similarly, the most educated groups had 64% (95% CI: 1.32 to 1.95) higher odds of enrollment than the least educated groups.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that despite major efforts by governments, health insurance schemes in low-and middle-income countries are generally not reaching the targeted underserved populations and predominantly supporting better-off population groups. Current health insurance designs should be carefully scrutinized, and the extent to which health insurance can be used to support the most vulnerable populations carefully re-assessed by countries, which are aiming to use health insurance schemes as means to reach their UHC goals. Furthermore, studies exploring best practices to include vulnerable groups in health insurance schemes are needed.

Registration

Not available

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Improving equity in service utilization and ensuring financial protection for all individuals regardless of their ability to pay are key objectives within the global Universal health coverage (UHC) goals. Universal health coverage is of critical societal importance both in high- and in low-income settings, where inequalities between the rich and poor seem particularly large [1, 2]. Health insurance schemes are currently receiving increased attention globally not only as a health financing mechanism but also as a strategy to achieve universal health coverage [3] and as a means to reduce inequities between population groups [4].

In the absence of clear international guidelines, many low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) have started implementing a mix of social, national and community-based/mutual health insurance schemes over the past 15 years. Traditional social health insurance, which originated in Europe, uses earmarked payroll taxes from the formal sector as part of its health financing arrangements. Despite the generally small size of the formal sector, this type of health financing scheme has been adapted in many low-income settings, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [5]. For example, in 2018, Zambia, which has an informal sector of almost 90%, passed the National Health Insurance bill which uses payroll taxes to improve access to quality health care for all its citizens [6, 7]. To extend health insurance coverage for those self-employed and the informal sector, community-based health insurance (CBHI) or mutual health insurance (MHI) have also emerged at various scales in Rwanda, Nepal, India, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mali and Senegal. CBHIs and MHI are typically voluntary schemes which target the informal sector and self-employed and their funds are pooled at the community level. Some countries such as Vietnam, Mexico and Peru have established noncontributory schemes using general tax revenues aimed at those not covered by social security schemes [8]. For example, in Thailand, there are three main health financing arrangements - a social security scheme for private formal sectors, a civil servants’ medical benefit scheme for civil servants and their families and a UHC scheme for those not affiliated with the other two schemes [9].

Current evidence of the impact of health insurance schemes in LMICs suggests some positive effects of insurance rollout on UHC goals [10,11,12,13,14]. Two recent reviews suggest that the reduction of financial barriers through CBHI and social health insurance improve service utilization and can protect its members from out-of-pocket expenditure [14, 15]. While these average impacts of health insurance schemes are certain, the extent to which these programs succeed in improving health and wellbeing of the most underserved population groups remains unclear [16, 17]. Knowledge and awareness of insurance programs, distance to health facilities, and payments associated with insurance schemes have been shown to be critical predictors of health insurance enrollment [18]. Meanwhile, these predicators might also undermine access of the most underserved groups to health insurance schemes.

In this manuscript, we systematically reviewed the literature on health insurance enrollment in LMICs to assess the extent to which current health insurance schemes reach poor and underserved populations.

Methods

Study Design

This study was designed as a systematic review and a meta-analysis of studies assessing the extent to which the most vulnerable populations are currently covered by health insurance schemes. We define vulnerable populations as the lowest group within the socioeconomic context (i.e., income, wealth quintile and education status in a country).

Eligibility criteria

This review included randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental, and observational studies related to health insurance enrollment in LMICs. The classification of countries as LMICs was based on the World Bank classification of per capita gross national income in 2019 (GNI per capita of $1,026 or less for low-income countries, GNI per capita between $1,026 and $3,995 for lower-middle income countries and for upper-middle income countries, the GNI per capita was $3,996-$12,376) [19]. We focused on studies that allowed the comparison of health insurance enrollment across groups with different socioeconomic status (income, wealth quintile, education status). We included health insurance schemes funded by the government including noncontributory health insurance and social health insurance schemes. Due to the popularity of community-based health insurances and mutual health insurances in LMICs, studies on such programs were included independent of their implementation scale. We restricted the studies to those published in English.

Studies were excluded if they only graphically displayed group differences in insurance enrollment. We also excluded papers exclusively focusing on private health insurance from the review. Studies which did not allow us to determine the type of health insurance (national, community-based, or private insurance schemes) were excluded.

Search strategy

We conducted electronic searches from June 2019 to October 2019 in PubMed, Web of Science, EconLit (for economics literature) and Google Scholar. The search strategy relied on keywords from a combination of medical subject headings and free text including terms such as “health insurance”, “socioeconomic status”, “enroll” and “reach”. We filtered the search to studies published between January 2010 and September 2019 and were conducted in LMICs. We focused on studies published from 2010 since other systematic reviews on health insurance focused on earlier years [11, 14]. The search strategy for PubMed is shown in Table S1.

Study selection and data extraction

Two independent authors screened all titles and abstracts of the initially identified articles to determine their eligibility for the inclusion criteria. The last author assisted in resolving any disagreement through a third review and after discussion with the review team. In the next phase, full articles were independently assessed for eligibility.

Two authors also independently extracted study information including type of scheme and its details, study design, year of data collection, relative enrollment rates of the poorest and least educated populations, type of point estimate and point estimate of enrollment for highest wealth and education groups compared to the lowest groups. Data were also extracted for non-overlapping populations (e.g. female vs male, urban vs rural). For studies that reported more than one adjusted point estimate, results from the least adjusted model were extracted in order to measure absolute enrollment gaps as consistently as possible.

Quality assessment

In order to assess study quality and risk of bias, we adapted the National Institutes of Health (NIH) quality assessment tool for cross-sectional and case studies [20]. The tool contains fourteen parameters addressing internal and external validity concerns such as sample size justification, adjustment of potential confounding variables and participation rate of eligible persons. Given that we were primarily interested in absolute enrollment rates by population group rather than adjusted models, we removed items on the checklist related to confounding and analytical biases and added two questions on representativeness of the data set used, which we deemed to be of critical importance for our analysis.

Data analysis

There were two stages in the analysis. First, we computed average enrollment rates of the poorest subpopulation as well as the absolute gaps in enrollment rates between the best-and worst-off subpopulations. In the second stage, we used random effects meta-analysis to analyze the odds of health insurance enrollment of the group with lowest socioeconomic status relative to the subgroup with the highest socioeconomic status.

Given that multiple enrollment estimates were available for some countries, we first used random-effects meta-analysis to aggregate individual study estimates into a single pooled country estimate, and then conducted country-level meta-analysis using either the pooled estimate from the first step, or, for countries where only one study was available, the single country estimate. We assessed heterogeneity for adjustment in point estimates through subgroup analysis of those studies which had adjusted vs non adjusted odds ratio. We conducted all meta-analyses using STATA version 16 and illustrated results using forest plots.

Results

Search for studies

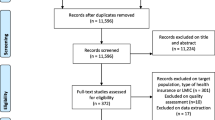

Figure 1 summarizes the main search process and results. Electronic searches of the four databases identified 1072 studies. After removing duplicates, 824 studies remained. 644 studies were excluded based on abstract and title review. There were 180 full text articles assessed for eligibility. Six studies were identified to be eligible for full-text assessment but they could not be retrieved. Hundred twenty-six studies did not report key variables of interest resulting in a final set of 48 studies.

Characteristics of included studies

Almost all the studies (46/48) analyzed were single-country analyses (Table S2). Thirty-four of the single-country studies were from Sub-Saharan Africa. Notably, 23 studies were from Ghana, two studies each from Rwanda, South Africa, Burkina Faso and Tanzania, one study each in Kenya, Cameroon and Senegal. Twelve studies were conducted in Asia: three studies were from India, two studies each in Vietnam and Bangladesh and one study in Nepal, Laos, China, Sri Lanka, and Iran. There was only one study from South America (Colombia). One study analyzed both Ghana and Senegal [21]. Most of the studies (39/48) were published on from 2014-2018.

More than half of the studies (31/48) used primary data while the rest used representative household survey data. With regards to the primary outcome of interest, 39 studies examined health insurance enrollment by various education groups and 44 studies by wealth groups. For education, most studies (31/39) had four education categories: no formal education, primary education, secondary education, or higher education. For these groupings, enrollment rates were compared between those without any formal education and then those with a secondary or higher education. For income or wealth, majority of the studies (36/44) grouped households into quintiles and then enrollment rates were compared between the richest and poorest subgroups.

Types of schemes and their policies for vulnerable groups

The included papers focused on 29 health insurance schemes in 17 countries as shown in Table 1. Most of the schemes (20/29) were implemented by either the central or sub-national government. The remaining 10 schemes were mutual or community health funds in which eight were organized by not-for-profit organizations and the other two by a research organization, and a health cooperative. Of the 25 schemes in which their year of establishment was reported by the studies, 21 were launched before the year 2010.

A majority of the schemes (25/29) were designed to target specifically the informal sector, poor households, and rural populations and/or provide either premium subsidization or exemption to vulnerable populations. Among these 25 schemes, three (Health Care for the poor in Vietnam, Subsidized Health Insurance in Colombia, and the Kenya National Hospital Insurance Fund) were established to provide 100% subsidy to the poor. The other five schemes were implemented by the central government which are targeted for specific groups such as the formal sector, students, and urban residents.

Health insurance enrollment rate among the most vulnerable groups

The enrollment rate into any type of health insurance scheme among the most vulnerable population group was 36% on average with an inter-quartile range of 28%. The enrollment rate varied from 10.3% in a district mutual fund in Burkina Faso to 87.8% in the subsidized regime of Colombia’ social health insurance which targets the poor (Figure 2). Furthermore, households in the lowest wealth or income quintile were on average 19 percentage points less likely to enroll compared to households in the highest socioeconomic group (Figure S1).

After data extraction, a total of 31 studies from 13 countries reporting odds ratio or logit coefficient comparing highest and lowest groups for wealth and education in health insurance enrollment were included in the meta-analysis. For wealth status, point estimates of the relative insurance enrollment were available from 28 studies covering 12 countries (Figure 3). Multiple point estimates were available for Bangladesh, Cameroon, Ghana, India, and Kenya. Figure S2 shows the results of the random effect meta-analysis used to create a single country-specific estimate for these countries. Across countries, households from the wealthiest subgroup had on average 61% higher odds (95% CI: 1.49 to 1.73) of enrollment into health insurance schemes than households in the poorest group of the same country.

There was high heterogeneity across countries (I-squared=91.0%; p-value<0.01). Most (8) of the countries had an odds ratio of enrollment for the richest groups to be over two times the odds of the enrollment for the poorest groups. Only the health insurance schemes in Iran and India had an odds ratio less than one (OR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.04 to 3.15 and OR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.67 to 1.12, respectively). The same patterns emerged when we examined enrollment status by educational attainment group. The enrollment gap between the least and most educated groups ranged from -6.9% to -41.2% (Figure S3), with an average gap of about 19 % percentage points. Point estimates of the relative insurance enrollment for education groups were available for 25 studies in 12 countries. As shown in Figure 4, the most educated groups had on average 64% (95% CI: 1.32 to 1.95) higher odds of enrollment than the least educated groups. The CBHI scheme in Burkina Faso had the highest odds ratio of 6.11 for the enrollment for the most educated compared to the least educated, whilst the lowest odds ratio between these two groups was 0.84 in Tanzania. There was high heterogeneity between studies (I-squared=88.2%; p-value<0.01). There were six countries, Bangladesh, Cameroon, Ghana, India, Kenya and Nepal, which had estimates from multiple studies for education groups (Figure S4).

Subgroup analysis for education comparing studies with crude versus studies with adjusted ORs showed some differences. The pooled unadjusted odds ratio was 2.32 (95% CI: 1.42 to 3.23) compared to the pooled odds ratio of 1.44 (95% CI: 1.24 to 1.63) in studies adjusting for sex, age, ethnicity, location, marital status, household size, religion, health status and employment status (Figure S5).

Quality assessment

All the studies included in the review were observational. Of the 48 studies, 20 were rated as ‘good’, whilst 27 were rated ‘fair’ (Table 2). Only one study was rated as ‘poor’. This study was removed from analysis. The alternative estimates with the full sample are included in File S6. All the studies had the basic elements related to having a clear research question, a defined study population, and selection criteria of participants. However, only 10 studies reported the participation rate of eligible persons. Few studies relied on large administrative population-based data. Studies were rated as ‘fair’ if the study population was not representative of the general population.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review with the aim of assessing the extent to which health insurance schemes are currently reaching the most vulnerable population groups in LMICs. We found 48 studies, which focused on 29 health insurance schemes from 17 LMICs allowing us to compare enrollment across socioeconomic groups, most of which were published after 2013. Overall, the results of our review are clear: current health insurance schemes reach only a relatively small proportion of the most vulnerable population groups.

The only scheme in which the enrolment rate was far lower for the wealthiest populations was the Colombian subsidized regime which exclusively targeted the poor and other vulnerable groups as those in the formal sector and self-employed workers with a steady income are required to obtain the contributory regime. Two features of the scheme which seem important are, first, that the scheme is mandatory for all those who are eligible to enroll. Second, during the period of analysis by Ruiz-Gomez et al, municipalities were using a mean proxy test to select beneficiaries into the scheme through the established social service beneficiaries’ identification system (Sistema de Identificación de los Beneficiarios de los Servicios Sociales, SISBEN )[63].

Even though virtually all the other insurance schemes analyzed directly target or subsidize the most vulnerable groups, better-off households have on average almost twice the odds of enrolling in health insurance compared to poorest households. For example, the Ghana health insurance scheme stipulates premium exemptions for indigents, the elderly above 70, pregnant women and children while the Rwanda Mutelle de Santé exempts the poorest 16% of households from premium payments. Other schemes such as those implemented in Nepal, Bangladesh and Burkina Faso have subsidized rates for the poorest households.

Despite these efforts, enrollment rates of the wealthiest subpopulations are higher than those of the most vulnerable population groups in all of these countries. These results are consistent with previous work on health insurance programs showing that enrollment and willingness to purchase health insurance in LMICs is pro-rich, which are explained by factors such as greater exposure of the rich to the media and their higher income levels to pay for health insurance premiums [14, 51, 64].

The current enrollment gaps should not necessarily be interpreted as evidence that current targeting efforts do not make enrollment easier for poor households. Rather, it demonstrates that these current measures appear insufficient to equitably include vulnerable populations in health insurance schemes. Given that most health insurance schemes in LMICs are heavily financed by central government revenues, the currently observed enrollment patterns essentially make health insurance a regressive policy, primarily subsidizing health care for better-off households. Further reductions in premiums and improving geographical access to health facilities could potentially increase uptake among poor and underserved populations [12]; other policy options include automatic (free) insurance enrollment of these groups or the direct provision of free health services for these groups.

Despite our best effort to review all of the recent evidence available, the findings presented in this manuscript have limitations. First, the included studies were retrospective and cross-sectional, and primarily focused on CBHI and national health insurance schemes. Second, due to the language restriction for publications in English, there was a limitation by the exclusion of articles published in other languages. In the past two decades, many LMICs in Latin America have implemented health insurance schemes such as non-contributory schemes for vulnerable populations [65]. Therefore, restricting the literature search to English may have underrepresented the inclusion of studies from this region which in turn may have underestimated health insurance enrollment of vulnerable populations. Thirdly, it was also quite striking that nearly half (23/48) of all studies identified focused on Ghana, while no studies were found on several other countries where similar insurance programs have been launched in the recent past. In addition, studies used highly heterogeneous ways of measuring wealth or income that may not be directly comparable. Our analysis also pooled data across different designs of insurance schemes and socioeconomic group definitions and therefore, represents an average across highly heterogeneous systems. In addition, nearly all the studies relied on self-reported data about wealth or income and educational status which could lead to misclassification due to recall bias. Lastly, another limitation of our study is the lack of longitudinal data that would have allowed evaluating whether there are countries that are successfully reducing inequalities in health insurance enrollment. Large longitudinal trend studies are needed to determine the contribution of health insurance schemes in reducing inequalities between the rich and poor over time

Despite these limitations, our findings are consistent with a larger analysis of the World Health Surveys conducted in the early 2000s which suggested that health insurance schemes continue to primarily benefit the better-off populations [66]. In their current form, health insurance schemes are thus unlikely to be viable mechanisms to promote universal health coverage. Challenges faced by current schemes include difficulties associated with identifying the most poor or vulnerable populations [67,68,69,70] as well as management of rollout and implementation at sub-national levels [71]. Increased financial, political, and institutional resources are likely needed to identify and reach underserved populations. In addition, simplified administrative processes for enrollment such as automatic enrollment after their identification could also facilitate the inclusion of underserved populations [72,73,74].

Conclusion

Although all recently introduced health insurance schemes LMICs aim at providing access to health services as well as financial protection to the most vulnerable populations, current coverage is low among the poor, and highly regressive in most countries. Experiences from countries suggest that current strategies to improve coverage of vulnerable populations in health insurance schemes have not achieved their aim of equity. Further investigation is needed to understand why these strategies are not reaching vulnerable groups. The evidence also suggests countries that are planning to establish health insurance schemes with the aim of equity for vulnerable populations might need to reevaluate their approach given the findings of this review.

Availability of data and materials

The data analyzed is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CBHI:

-

Community based health insurance

- LMICs:

-

Low-and Middle-income countries

- MHI:

-

Mutual Health Insurance

- NCS:

-

Non-Contributory Scheme

- NPO:

-

Not-for-profit

- NR:

-

Not Reported

- SHI:

-

Social Health Insurance

- UHC:

-

Universal Health Coverage

References

McIntyre D, Garshong B, Mtei G, Meheus F, Thiede M, Akazili J, et al. Beyond fragmentation and towards universal coverage: insights from Ghana, South Africa and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(11):871–6.

McIntyre D, Obse AG, Barasa EW, Ataguba JE: Challenges in Financing Universal Health Coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa. In.: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Kutzin J, Yip W, Cashin C: Alternative Financing Strategies for Universal Health Coverage. In: World Scientific Handbook of Global Health Economics and Public Policy. edn.: 267-309.

Carrin G, Waelkens MP, Criel B. Community-based health insurance in developing countries: a study of its contribution to the performance of health financing systems. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(8):799–811.

Yazbeck AS, Savedoff WD, Hsiao WC, Kutzin J, Soucat A, Tandon A, et al. The Case Against Labor-Tax-Financed Social Health Insurance For Low- And Low-Middle-Income Countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(5):892–7.

Informality and Poverty in Zambia: Findings from the 2015 Living Conditions and Monitoring Survey, October 2018. In. Geneva: International Labor Office; 2019.

Government of Zambia: The National Health Insurance Act 2018. In., vol. Acts of Parliament (Post. Lusaka. Zambia: Government of Zambia; 1997. p. 2018.

Dmytraczenko TA. Gisele: Health care for all: toward universal health coverage and equity in Latin America and the Caribbean: evidence from selected countries. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2015.

World Health Organization: Global Spending on Health: A World in Transition. In. Geneva, Switzerland World Health Organization; 2019.

Erlangga D, Suhrcke M, Ali S, Bloor K. The impact of public health insurance on health care utilisation, financial protection and health status in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0219731.

Acharya A, Vellakkal S, Taylor F, Masset E, Satija A, Burke M, Ebrahim S: Impact of national health insurance for the poor and the informal sector in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review; 2012.

Adebayo EF, Uthman OA, Wiysonge CS, Stern EA, Lamont KT, Ataguba JE: A systematic review of factors that affect uptake of community-based health insurance in low-income and middle-income countries. BMC health services research 2015, 15(1):543-543.

Lu C, Chin B, Lewandowski JL, Basinga P, Hirschhorn LR, Hill K, et al. Towards universal health coverage: an evaluation of Rwanda Mutuelles in its first eight years. PloS one. 2012;7(6):1–16.

Spaan E, Mathijssen J, Tromp N, McBain F, ten Have A, Baltussen R. The impact of health insurance in Africa and Asia: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(9):685–92.

Wiysonge CS, Paulsen E, Lewin S, Ciapponi A, Herrera CA, Opiyo N, Pantoja T, Rada G, Oxman AD: Financial arrangements for health systems in low-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2017, 9:Cd011084.

Wagstaff A, Pradhan M: Health insurance impacts on health and nonmedical consumption in a developing country : Health insurance impacts on health and non-medical consumption in a developing country. In: Policy, Research working paper ; no WPS 3563. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2005.

Wagstaff A. Social health insurance reexamined. Health economics. 2010;19(5):503–17.

Fenny AP, Yates R, Thompson R. Social health insurance schemes in Africa leave out the poor. International Health. 2018;10(1):1–3.

Country classification [https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups]

[https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools]

Parmar D, Williams G, Dkhimi F, Ndiaye A, Asante FA, Arhinful DK, et al. Enrolment of older people in social health protection programs in West Africa--does social exclusion play a part? Social science & medicine. 1982;2014(119):36–44.

Mahmood SS, Hanifi SMA, Mia MN, Chowdhury AH, Rahman M, Iqbal M, Bhuiya A: Who enrols in voluntary micro health insurance schemes in low-resource settings? Experience from a rural area in Bangladesh. Global Health Action 2018, 11(1):1-10.

Sarker AR, Sultana M, Mahumud RA, Ahmed S, Islam Z, Morton A, et al. Determinants of enrollment of informal sector workers in cooperative based health scheme in Bangladesh. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):1–12.

Cofie P, De Allegri M, Kouyaté B, Sauerborn R. Effects of information, education, and communication campaign on a community-based health insurance scheme in Burkina Faso. Global health action. 2013;6(1):1–12.

Parmar D, De Allegri M, Savadogo G, Sauerborn R. Do community-based health insurance schemes fulfil the promise of equity? A study from Burkina Faso. HEALTH POLICY AND PLANNING. 2014;29(1):76–84.

Oraro T, Ngube N, Atohmbom GY, Srivastava S, Wyss K. The influence of gender and household headship on voluntary health insurance: the case of North-West Cameroon. Health Policy and Planning. 2018;33(2):163–70.

Jin Y, Hou Z, Zhang D. Determinants of Health Insurance Coverage among People Aged 45 and over in China: Who Buys Public, Private and Multiple Insurance. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(8):1–15.

Ruiz Gomez F, Zapata Jaramillo T, Garavito Beltran L. Colombian health care system: results on equity for five health dimensions, 2003-2008. Rev Panam Salud Publuca. 2013;33(2):107–99.

Fenny AP. Live to 70 Years and Older or Suffer in Silence: Understanding Health Insurance Status Among the Elderly Under the NHIS in Ghana. Journal of aging & social policy. 2017;29(4):352–70.

Akazili J, Welaga P, Bawah A, Achana FS, Oduro A, Awoonor-Williams JK, et al. Is Ghana's pro-poor health insurance scheme really for the poor? Evidence from Northern Ghana. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14(637):1–9.

Dixon J, … EYTE, Planning, Undefined: Ghana's National Health Insurance Scheme: helping the poor or leaving them behind? journalssagepubcom 2011.

Dixon J, Luginaah I: Determinants of Health Insurance Enrolment in Ghana' s Upper West Region. In.; 2014.

Amo T. The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in the Dormaa Municipality, Ghana: why some residents remain uninsured? Global journal of health science. 2014;6(3):82–9.

Kotoh AMAM, … SVdGfei, Undefined, Van der Geest S: Why are the poor less covered in Ghana's national health insurance? A critical analysis of policy and practice. equityhealthjbiomedcentralcom 2016, 15(1):34-46.

Jehu-Appiah C, Aryeetey G, Spaan E, de Hoop T, Agyepong I, Baltussen R. Equity aspects of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana: Who is enrolling, who is not and why? SOCIAL SCIENCE & MEDICINE. 2011;72(2):157–65.

Duku SKOSKO, van Dullemen CE, Fenenga C. Does health insurance premium exemption policy for older people increase access to health care? Evidence from Ghana. JOURNAL OF AGING & SOCIAL POLICY. 2015;27(4):331–47.

Kusi A, Fenny A, Arhinful DK, Asante FA, Parmar D. Determinants of enrolment in the NHIS for women in Ghana – a cross sectional study. International Journal of Social Economics. 2018;45(9):1318–34.

Kumi-Kyereme A, Amo-Adjei J. Health JA-A: Effects of spatial location and household wealth on health insurance subscription among women in Ghana. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13(1):221–9.

Amu H, Dickson KS. Health insurance subscription among women in reproductive age in Ghana: do socio-demographics matter? Health Economics Review. 2016;6(24):1–8.

Sarpong N, Loag W, Fobil J, Meyer CG, Adu-Sarkodie Y, May J, Schwarz NG: National health insurance coverage and socio-economic status in a rural district of Ghana. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2010.

Seddoh A, Sataru F. Mundane? Demographic characteristics as predictors of enrolment onto the National Health Insurance Scheme in two districts of Ghana. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):330–6.

Van der Wielen N, Channon AA, Falkingham J. Universal health coverage in the context of population ageing: What determines health insurance enrolment in rural Ghana? BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):657–70.

Khalid M. Three Essays on the Informal Sector: University of Manitoba; 2017.

Boateng D, Awunyor-Vitor D. Health insurance in Ghana: evaluation of policy holders' perceptions and factors influencing policy renewal in the Volta region. International journal for equity in health. 2013;12(50):1–10.

Manortey S, VanDerslice J, Alder S, Henry KA, Crookston B, Dickerson T, et al. Spatial Analysis of Factors Associated with Household Subscription to the National Health Insurance Scheme in Rural Ghana. Journal of public health in Africa. 2014;5(1):353–61.

van der Wielen N, Channon AA, Falkingham J. Does insurance enrolment increase healthcare utilisation among rural-dwelling older adults? Evidence from the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana. BMJ GLOBAL HEALTH. 2018;3(1):1–9.

Kuuire VZ, Tenkorang EY, Rishworth A, Luginaah I, Yawson AE. Is the Pro-Poor Premium Exemption Policy of Ghana's NHIS Reducing Disparities Among the Elderly? POPULATION RESEARCH AND POLICY REVIEW. 2017;36(2):231–49.

Parmar D, Williams G, Dkhimi F, Ndiaye A, Asante FA, Arhinful DK, et al. Enrolment of older people in social health protection programs in West Africa--does social exclusion play a part? Social Science and Medicine. 2014;119:36–44.

Panda P, Chakraborty A, Dror DM, Bedi AS: Enrollment in Community-Based Health Insurance Schemes in Rural Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India. Health Policy and Planning 2014, 29(8):960-974.

Ghosh S: Publicly-Financed Health Insurance for the Poor Understanding RSBY in Maharashtra. 2014, 46.

Nosratnejad S, Rashidian A, Mehrara M, Jafari N, Moeeni M, Babamohamadi H. Factors Influencing Basic and Complementary Health Insurance Purchasing Decisions in Iran: Analysis of Data From a National Survey. WORLD MEDICAL & HEALTH POLICY. 2016;8(2):179–96.

Oraro T, Wyss K: How does membership in local savings groups influence the determinants of national health insurance demand? A cross-sectional study in Kisumu, Kenya. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR EQUITY IN HEALTH 2018, 17(1):170-170.

Alkenbrack S, Jacobs B, Lindelow M: Achieving universal health coverage through voluntary insurance: what can we learn from the experience of Lao PDR? BMC health services research 2013, 13(1):521-521.

Adhikari N, Wagle RR, Adhikari DR, Thapa P, Adhikari M. Factors Affecting Enrolment in the Community Based Health Insurance Scheme of Chandranigahapur Hospital of Rautahat District. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2019;16(41):378–84.

Finnoff C. Gendered Vulnerabilities after Genocide: Three Essays on Post-conflict Rwanda: University of Massachusetts; 2010.

Mladovsky P, Soors W, Ndiaye P, Ndiaye A, Criel B. Can social capital help explain enrolment (or lack thereof) in community-based health insurance? Results of an exploratory mixed methods study from Senegal. Social science & medicine. 1982;2014(101):18–27.

Goudge J, Alaba OA, Govender V, Harris B, Nxumalo N, Chersich MF. Social health insurance contributes to universal coverage in South Africa, but generates inequities:a survey among members of a government employee insurance scheme. International journal for Equity in Health. 2018;17(1):1–13.

Govender V, Chersich MF, Harris B, Alaba O, Ataguba JE, Nxumalo N, et al. Moving towards universal coverage in South Africa? Lessons from a voluntary government insurance scheme. Global Health Action. 2013;6(1):109–19.

Bendig M, Arun T. Enrolment in Micro Life and Health Insurance: Evidences from Sri Lanka. Econstor. 2011;5427:1–30.

Macha J, Kuwawenaruwa A, Makawia S, Mtei G, Borghi J. Determinants of community health fund membership in Tanzania: a mixed methods analysis. BMC health services research. 2014;14(1):538–49.

Nguyen THT-H, Leung S. Dynamics of Health Insurance Enrollment in Vietnam, 2004-2006. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy. 2013;18(4):594–614.

Nguyen H, Knowles J. Demand for voluntary health insurance in developing countries: The case of Vietnam's school-age children and adolescent student health insurance program. SOCIAL SCIENCE & MEDICINE. 2010;71(12):2074–82.

Montenegro Torres FBA, Oscar: Colombia Case Study : The Subsidized Regime of Colombia’s National Health Insurance System. In., vol. UNICO Studies Series;No. 15. Washington, DC.: World Bank; 2013.

Barasa E, Kazungu J, Nguhiu P, Ravishankar N. Examining the level and inequality in health insurance coverage in 36 sub-Saharan African countries. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(4):e004712.

Bossert T, Blanchet N, Sheetz S, Pinto D, Cali J, Cuevas RP. Comparative Review of Health System Integration in Selected Countries in Latin America In. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank; 2014.

El-Sayed AM, Vail D, Kruk ME. Ineffective insurance in lower and middle income countries is an obstacle to universal health coverage. J Glob Health. 2018;8(2):020402.

Aryeetey GC, Jehu-Appiah C, Spaan E, D’Exelle B, Agyepong I, Baltussen R: Identification of poor households for premium exemptions in Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: empirical analysis of three strategies. 2010, 15(12):1544-1552.

Marwa B, Njau B, Kessy J, Mushi D. Feasibility of introducing compulsory community health fund in low resource countries: views from the communities in Liwale district of Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13(1):298.

Umeh CA. Identifying the poor for premium exemption: a critical step towards universal health coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa. Global Health Research and Policy. 2017;2(1):2.

Salari P, Akweongo P, Aikins M, Tediosi F. Determinants of health insurance enrolment in Ghana: evidence from three national household surveys. Health Policy and Planning. 2019;34(8):582–94.

Maluka SO: Why are pro-poor exemption policies in Tanzania better implemented in some districts than in others? International journal for equity in health 2013, 12:80-80.

Sood N, Wagner Z: Social health insurance for the poor: lessons from a health insurance programme in Karnataka, India, BMJ GLOBAL HEALTH 2018, 3(1):e000582-e000582.

O'Donnell O. Access to health care in developing countries: breaking down demand side barriers. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2007;23:2820–34.

Nsiah-Boateng E, Nonvignon J, Aryeetey GC, Salari P, Tediosi F, Akweongo P, Aikins M: Sociodemographic determinants of health insurance enrolment and dropout in urban district of Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Health economics review 2019, 9(1):23-23.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

DOA was supported by SINERGIA grant number CRSII5_183577. The funder did not have any role in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DOA, BK and FK designed the systematic review. BK led the earlier stages of conducting searches and data extraction DOA wrote the first draft of the article and all co-authors critically reviewed and major contributions to it. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table S1.

PubMed search strategy.

Additional file 2. Table S2.

Characteristics of included studies.

Additional file 3. Figure S1.

Absolute percentage enrollment gap at the population level between the lowest and highest wealth groups.

Additional file 4. Figure S2.

Forest plot showing countries with multiple estimates.

Additional file 5. Figure S3.

Absolute percentage enrollment gap at the population level between the least and most educated groups.

Additional file 6. Figure S4.

Forest plot showing countries with multiple estimates for education.

Additional file 7. Figure S5.

Forest plot showing subgroup analysis of adjusted and crude odds ratio.

Additional file 8. File S6.

Figures showing estimates regardless of quality rating.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Osei Afriyie, D., Krasniq, B., Hooley, B. et al. Equity in health insurance schemes enrollment in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Equity Health 21, 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01608-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01608-x