Abstract

Background

To date, no culture-specific food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) are available in North Africa. The aim of this study was to adapt and examine the reproducibility and validity of an FFQ or use in the Moroccan population.

Methods

The European Global Asthma and Allergy Network (GA2LEN) FFQ was used to assess its applicability in Morocco. The GA2LEN FFQ is comprised of 32 food sections and 200 food items. Using scientific published literature, as well as local resources, we identified and added foods that were representative of the Moroccan diet. Translation of the FFQ into Moroccan Arabic was carried out following the World Health Organization (WHO) standard operational procedure. To test the validity and the reproducibility of the FFQ, 105 healthy adults working at Hassan II University Hospital Center of Fez were invited to answer the adapted FFQ in two occasions, 1 month apart, and to complete three 24-h dietary recall questionnaires during this period. Pearson correlation, and Bland-Altman plots were used to assess validity of nutrient intakes. The reproducibility between nutrient intakes as reported from the first and second FFQ were calculated using intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). All nutrients were log-transformed to improve normality and were adjusted using the residual method.

Results

The adapted FFQ was comprised of 255 items that included traditional Moroccan foods. Eighty-seven adults (mean age 27.3 ± 5.7 years) completed all the questionnaires. For energy and nutrients, the intakes reported in the FFQ1 were higher than the mean intakes reported by the 24-h recall questionnaires. The Pearson correlation coefficients between the first FFQ and the mean of three 24-h recall questionnaires were statistically significant. For validity, de-attenuated correlations were all positive, statistically significant and ranging from 0.24 (fiber) to 0.93 (total MUFA). For reproducibility, the ICCs were statistically significant and ranged between 0.69 for fat and 0.84 for Vitamin A.

Conclusion

This adapted FFQ is an acceptable tool to assess usual dietary intake in Moroccan adults. Given its representativeness of local food intake, it can be used as an instrument to investigate the role of diet on health and disease outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The burden of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCD) in African countries continues to rise [1]. The epidemiological profile of North Africa increasingly mirrors that of more developed societies, where cancer, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases represent a major societal and health burden. Prevalence of these, and other NCDs related to diet, has continuously increased in the last two decades [2,3,4], but there is scant scientific evidence on the role of dietary habits on disease risk and prevalence in the Moroccan population [5, 6].

Food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) are a helpful instrument to ascertain usual dietary intake and its relationship with health and disease outcomes [7, 8]. Although FFQs are widely used in Europe and America [9, 10], nutritional epidemiology in Morocco remains hindered by the lack of locally representative dietary questionnaires, particularly FFQs. We are only aware of one FFQ recently developed to ascertain usual fruit and vegetable intake in Moroccan adults [11]. To date, the vast majority of what we know about dietary habits and chronic disease in this country relates to their association with Ramadan and obesity [2, 12].

The rapid socio-economic transition in North Africa has been accompanied by changes in the way the population eat, which are not easily captured with dietary questionnaires from, for example, high income countries. Morocco is a fast-growing developing country with a diet characterised by intake of vegetable-based dish, spices, and meat [11,12,13], and a rich combination of very traditional dishes with a more modern cuisine. Having FFQs that reflect such transitions and cultural features are urgently needed to identify regionally and locally relevant dietary risk factors for health and disease outcomes. To implement these FFQs, the validity and reproducibility of the instrument needs to be assessed [14, 15].

Our study was aimed at adapting the international GA2LEN FFQ to include staple foods consumed in Morocco, and at validating it in a sample of health Moroccan adults.

Methods

Participants

One hundred five adults working at Hassan II University Hospital Center of Fez were invited to answer the three 24-Hour Recall and the FFQ in two occasions. Eligibility to take part in the study was defined as having a regular diet over the previous 12 months and not have used any medications known to affect food intake or appetite during this period. The subjects had a stable weight. Data collection was conducted over a period of 4 months (July to October) in 2009.

FFQ adaptation

The Global Asthma and Allergy Network (GA2LEN) FFQ was adapted to reflect the Moroccan diet. The GA2LEN FFQ was designed to be used as a single, common instrument to assess dietary intake across Europe [9]. It was initially piloted and validated in five European countries, and it has been subsequently used in several multi-national studies including high and low income countries [16].

To adapt the GA2LEN FFQ to the Moroccan diet we compiled information published in the scientific literature on usual foods commonly consumed in Morocco and these were added to each section. In order to retain its international comparability, several food items from the original GA2LEN FFQ were kept in each of the sections even though they were not necessarily relevant to the Moroccan diet (e.g. pork or alcohol intake).

The Standard Operational Procedure (SOP) of the World Health Organization [17] was followed for the forward and back translations from English to Moroccan Arabic. A first translation from English into Moroccan Arabic (version 1) was carried out by a bilingual person. This version was then tested amongst five people from the respiratory unit of the University Hospital of Fez. Doubts and difficulties in answering the questions were investigated and after this initial assessment, a second Arabic version was produced (version 2). To improve the identification of foods relevant to the Moroccan population, the research team in Fez also visited several local markets and supermarkets to identify common brand names and foods that could be relevant and were added accordingly, adding up to a total of 255 food items in the FFQ (Table 1). Subsequent back-translation into English was performed by another translator with a good knowledge of English but who had not seen the FFQ before. A final draft of the FFQ (version 3) was agreed in Moroccan Arabic and English (Table 1).

Each food item in the FFQ was assigned a portion size using standard local household units such as plate, bowl, spoons of different size (tablespoon, teaspoon), tea-pot, tea-glass, and glass of water, as well as using photographs from a booklet (‘Food and typical preparations of the Moroccan population’ [14].

Frequency of dietary intake reported in the FFQ was estimated by selecting one of eight categories: never, once to three times per month, once a week, twice to four per week, five to six times per week, once per day, twice to three times, more than four times.

Validation of the FFQ

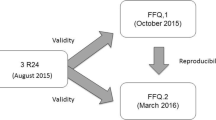

The FFQ was validated against the average of three 24-h recall questionnaires over a period of 1 month (Fig. 1). Participants were first asked to answer a 24-h recall questionnaire, where they reported all the foods and beverages consumed the day before, providing qualitative (e.g. type of food) and quantitative (e.g. portions) details. Each of the three 24-h recall questionnaires was administered 10 days apart, on two working days and 1 week-end day. The recalled food items were assigned to the food groups of the adapted FFQ.

The FFQ was completed in two occasions, a month apart, a day after participants completed the first and last 24-h recall questionnaires.

Nutritional composition data for Moroccan foods

Available Food Composition Tables from Morocco were used to derive nutrient composition for several traditional dishes and for some modern products [14, 15]. Additional information needed for non-traditional (‘modern’) foods was obtained from other regional sources of data, namely the Tunisian food composition table [18], the food composition table for African countries (FAO) [19], the French food composition table (CIQUAL) [20] and the United States department of agriculture nutrient database (USDA) [21].

To calculate total energy intake (TEI), macro-, and micro-nutrient intakes, we created a syntax using the SPSS.20 software. First, the amount of servings consumed was estimated using the standard food portion sizes and these were converted into grams per day [14]. For seasonal foods, participants were asked to answer the question based on intake when these foods were available. The daily intake was calculated according to the number of months per year that each seasonal food was available. TEI and nutrient intakes were calculated by multiplying the frequency of consumption of each food item by the content (per 100 g) and by the specified portion, and then adding the contribution from all food items.

Socio-demographic characteristics

The FFQ had an additional section enquiring about general characteristics namely age, sex, educational level, and occupation. To estimate body mass index (BMI), height and weight were measured using a calibrated equipment (stadiometer and weighing scale, respectively) and BMI was derived using the formula weight (kg) divided by height2 (m2).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive results were expressed as means standard deviations, or as percentages and frequencies for continuous and qualitative variables, respectively.

The mean daily intake of the three 24-h recall questionnaires was used as a representative average of the consumption reported in these questionnaires. Descriptive means and standard deviations of nutrient intakes estimated by the FFQ the first and second time (FFQ1 and, FFQ2), and the average of the three 24-h recall questionnaires are presented as untransformed values. As nutrient variables were not normally distributed these were log-transformed (log10) to reduce skewness and optimize the normality of the distribution.

Validity of the FFQ1 was compared with the average of three 24-h recall questionnaires using Pearson correlation coefficients. Adjustment correlation coefficients for TEI were calculated using the residual method [22] (with TEI as the independent variable and the nutrient as the dependent variable). Energy adjusted intakes were calculated by adding the mean nutrient intake to the residual derived from the regression analysis. The de-attenuated correlations [23] were calculated to remove the within-person variability found in the 24-h recall questionnaires using the following formula:

r t is the corrected correlation between the energy adjusted nutrient derived from the FFQ and 24-h recall questionnaires, r 0 is the observed correlation, r is the ratio of estimated within-person and between- person variation in nutrient intake derived from the three 24-h recall questionnaires, and n is the number of replicated recalls (n = 3).

Bland–Altman plots [24, 25] were used to assess agreement between the two methods. For this analysis, the average values of FFQ1 and three 24 Hour Recalls ((FFQ1 + Mean 24 HRs)/2) were plotted against the difference in intake between the two methods, and the limits of agreements (mean difference ± 1.96 SD (differences)) were used to show how large the disagreements between the two methods.

For the reproducibility of the FFQ, the agreement between FFQ1 and FFQ2 was assessed by Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients and intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) of transformed nutrients and energy-adjusted nutrient intakes. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0.

Participant’s consent and ethics

All participants were informed about their role in the study and gave formal consent before being interviewed. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at University of Fez.

Results

The final version of the adapted FFQ contained 255 foods, which were classified into 32 groups as follows: (1) bread, (2) breakfast with grains, (3) couscous, (4) pasta, (5) cake, (6) rice, (7) sugar, (8) sweets without chocolate, (9) chocolate, (10) vegetable oil, (11) margarine and vegetable fat, (12) butter and animals fat, (13) dried fruit, (14) legumes, (15) vegetables, (16) potatoes, (17) fruits, (18) juice, (19) non-alcoholic beverages, (20) coffee/tea, (21) beer, (22) wine, (23) other-alcoholic beverages, (24) red meat, (25) poultry, (26) sekat (offal), (27) fish, (28) eggs, (29) milk of cow/milk of soya, (30) cheese, (31) other dairy products, and (32) miscellaneous foods (Table 1).

A total of 87 participants completed all the dietary questionnaires (two FFQs and three24-h recall questionnaires). Most of the participants were females (70.1%) and young adults (mean age 27.3 ± 5.7 years). Over two thirds of participants (70.6%) had a normal BMI (Table 2). Eighteen subjects did not complete the second FFQ, with the main reason being declining to participate again (n = 12), or not being available after several attempts were made to contact them (n = 6).

The mean intake of TEI, macro-nutrients and micro-nutrients measured by FFQ1, FFQ2, and the 24-h recall questionnaires are presented in Tables 3. For TEI and nutrients intakes, the means reported in the FFQ1 were higher than the means reported using the average of the three 24-h recall questionnaires. The Bland-Altman plots for energy, and macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fat) are shown in Fig. 2. The Bland Altman plots confirmed an over-estimation of nutrient intakes consumptions by the FFQ.

Correlations between nutrient intakes derived from the FFQ1 and the mean of the 24-hour recall questionnaires are presented in Table 4. Crude correlation coefficients between the two methods varied from 0.23 (fiber) to 0.89 (total monounsaturated fatty acids [MUFA]), and were statistically significant. Adjusting for TEI was statistically significant for all nutrients but it decreased the value of correlation coefficients. However, de-attenuation (adjustment for residual measurement error) increased all correlation coefficients, ranging from 0.24 (fiber) to 0.93 (total MUFA).

The intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for both the unadjusted and the energy adjusted nutrient intakes estimated from FFQ1 and FFQ2 were presented in Table 5. The Pearson correlations (unadjusted) between nutrient intakes assessed by two FFQ varied from 0.62 (carbohydrates) to 0.76 (Vitamin A). Adjusting for total energy intake decreased all correlation coefficients, ranging from 0.53 (fat) to 0.73 (Vitamin A). The ICCs unadjusted ranged from 0.76 (carbohydrates) to 0.86 (Vitamin A and Vitamin C). The ICCs energy adjusted ranged from 0.69 (fat) to 0.84 (Vitamin A). All correlations were statistically significant.

Discussion

Our study described the process of adaptation of the international GA2LEN FFQ for use in Moroccan adults, and its relative validity and reproducibility to estimate usual food intake. The adapted FFQ contained 255 items, including staple foods consumed by the Moroccan population. The FFQ was classified into 32 food groups or sections, to mirror the structure of the GA2LEN FFQ, which facilitates international comparability. To our knowledge, this is the first FFQ in Morocco to include a comprehensive list of both traditional and ‘modern’ foods, providing a reasonable assessment of relative dietary intake over a 1-year period. We are aware of another FFQ developed in Morocco by Landais et al., but it is limited to intake of fruits and vegetables only [11]. The energy adjusted Pearson correlation between the FFQ and the mean 24-HRs showed that the relative validity findings were moderately consistent across the majority of nutrients, they ranged between 0.19 for fat to 0.86 for total MUFA, and these observed values were comparable to other FFQs validation studies [26,27,28].

The nutrient intakes reported with the use of the FFQ were higher than those reported using the 24-h recall questionnaires. This over-reporting is not uncommon when validating an FFQ with a relatively large number of food items [26, 29,30,31,32,33]. We used the average of three 24-h recall questionnaires, which is considered an acceptable number of days to capture usual intake [34]. A systematic review found that 75% of validation studies use the 24-h recall questionnaires as reference method against FFQs [35], preferred for the accuracy to capture daily consumption of a varied diet, and for their relatively easier administration and analysis compared to other dietary questionnaires. The FFQ and the 24-h recall questionnaire have some differences in their error sources, which make them sufficiently independent [36]. Both instruments are prone to memory bias (long-term vs short term in the FFQ vs the 24-h recall questionnaire, respectively) and have differences in the perception of portion sizes (usually pre-defined in the FFQ) [35, 37, 38]. The 24-h recall questionnaire method is based on open-ended questions; while the FFQ is usually designed to have close-ended questions.

The acceptable correlations between the the FFQs and 24-HRs and the overestimation of energy and nutrient intakes between the two methods were confirmed by the Bland-Altman plots. These figures indicated a positive mean difference for TEI and macronutrients. These results are in agreement with those reported by other studies [39,40,41].

Since no dietary method can assess nutrient intake without error [35], we used energy adjusted nutrient estimates in our analyses as a way to reduce correlated errors between the two dietary methods [22, 38]. Energy-adjustment decreased correlation coefficients for all nutrients, which often happens when variability is more related to systematic errors of under/overestimation than to energy intake [42,43,44]. Similarly, other studies have not reported that energy-adjusted estimates improved crude correlations [45,46,47]. The de-attenuated correlations were increased because of the correction for the day to day variation in intakes.

The reproducibility of the FFQ was examined by the administration of the questionnaire in two occasions, 1 month apart. As reported in other studies [48, 49], we found that the estimates observed in FFQ1 were slightly higher than in the second FFQ. This could be partly explained by the level of engagement of the participants and the attention required to complete the FFQ in full. The ICCs showed a good level of agreement for the reporting of macro- and micronutrients, ranging from 0.69 (fat) to 0.75 (proteins for macro-nutrients, and over 0.7 for most micro-nutrients, suggesting that the FFQ has a good repeatability and reproducibility [50].

Our study has several strengths. The structure of the FFQ was adapted from the international GA2LEN FFQ, whose applicability has been demonstrated in multinational studies in high [9] and low income countries [51]. In order to make the FFQ representative of the Moroccan population, we endeavored to identify traditional foods that are part of the staple diet of the country, while also maintaining the international structure of the food classification to facilitate international comparisons. We followed a strict protocol to ensure the FFQ was correctly translated into Moroccan Arabic, which is different from the written and spoken Arabic in other North African countries. The FFQ also takes into account seasonal variations in food consumption, an important feature in North Africa where seasonality strongly influences dietary choices.

We acknowledge this validation study has some limitations. The FFQ captures usual intake of foods over a longer period of time than a 24-h recall questionnaire, which could lead to errors in the results. We compared the FFQ to the average intake reported in three 24-h recall questionnaires. Although this is an acceptable number of interviews, several studies recommend seven recall days (replicates) to capture a better estimate of the habitual intake. However, three recording days per subject are considered feasible and sufficient to estimate within-person variability (day-to-day variability). Due to the length of the validation study (1 month), some seasonal variations might not have been captured accurately with the 24-h recall questionnaire. This may negatively impact the correlation results, reflecting differences between the two instruments, rather than limitations of the FFQ. The length of the FFQ (255 food items) might have discouraged the participants to respond it fully. We designed the FFQ bearing in mind the current gap in nutritional epidemiology in North Africa, creating a tool that captures the usual diet of Morocco, and that it estimates intake of other foods that are associated with the nutritional transition of the region. Finally, the majority of the study sample was comprised of women with a high level of education. This does not represent the general population of Morocco, where illiteracy and poverty are common. The use of the FFQ in the general population would probably require a close interaction between an interviewer and the participant to overcome communication and educational limitations.

Conclusions

This adaptation and validation study showed that the FFQ has a good relative validity and a good reproducibility for most nutrients. It is the first complete and validated tool to assess usual dietary intake in the Moroccan population that includes a wide range of traditional, as well as more ‘modern’ food items. Given its representativeness of local foods and habits, it can be used as an instrument to assess the relation of dietary habits and diseases in which diet might play a role.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- EPIC:

-

European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization

- FCT:

-

Food composition table

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- GA2LEN:

-

The European Global Asthma and Allergy Network

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficient

- MUFA:

-

Monounsaturated fatty acids

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- SFA:

-

Saturated fatty acids

- SOP:

-

The standard operational procedure

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Reshma N, Toshiko K. Non-communicable diseases in Africa: youth are key to curbing the epidemic and achieving sustainable development. Policy Brief. 2015;

Belahsen R. Nutrition transition and food sustainability. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73(3):385–8.

Boutayeb A, Boutayeb S. The burden of non communicable diseases in developing countries. Int J Equity Health. 2005;4(1):2.

El Rhazi K, Nejjari C, Zidouh A, Bakkali R, Berraho M, Barberger Gateau P. Prevalence of obesity and associated sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in Morocco. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(1):160–7.

Afshin A, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Fahimi S, Shi P, Powles J, Singh G, Yakoob MY, Abdollahi M, Al-Hooti S, et al. The impact of dietary habits and metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular and diabetes mortality in countries of the Middle East and North Africa in 2010: a comparative risk assessment analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e006385.

Mokhtar N, Elati J, Chabir R, Bour A, Elkari K, Schlossman NP, Caballero B, Aguenaou H. Diet culture and obesity in northern Africa. J Nutr. 2001;131(3):887S–92S.

Cade JE, Burley VJ, Warm DL, Thompson RL, Margetts BM. Food frequency questionnaires: a review of their design, validation and utilisation. Nutr Res Rev. 2004;17(1):5–22.

Jee-Seon S, Kyungwon O, Hyeon Chang K. Dietary assessment methods in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014009.

Garcia-Larsen V, Luczynska M, Kowalski ML, Voutilainen H, Ahlström M, Haahtela T, Toskala E, Bockelbrink A, Lee HH, Vassilopoulou E, et al. Use of a common food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to assess dietary patterns and their relation to allergy and asthma in Europe: pilot study of the GA2LEN FFQ. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(6):750–6.

Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, McIntosh A, Rosenfeld S. Comparative validation of the block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires. The eating at America’s table study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(12):1089–99.

Landais E, Gartner A, Bour A, McCullough F, Delpeuch F, Holdsworth M. Reproducibility and relative validity of a brief quantitative food frequency questionnaire for assessing fruit and vegetable intakes in north-African women. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27:152–9.

Benjelloun S. Nutrition transition in Morocco. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(1A):135–40.

Andersen LF, Solvoll K, Johansson LR, Salminen I, Aro A, Drevon CA. Evaluation of a food frequency questionnaire with weighed records, fatty acids, and alpha-tocopherol in adipose tissue and serum. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(1):75–87.

Neve J: Aliments et préparations typiques de la population marocaine: Outil pour estimer la consommation alimentaire.; 2008.

El Khayate R: Contribution à l'élaboration d’une table de composition des aliments au Maroc; 1948.

Palmer SC, Ruospo M, Campbell KL, Garcia Larsen V, Saglimbene V, Natale P, Gargano L, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Tonelli M, et al. Nutrition and dietary intake and their association with mortality and hospitalisation in adults with chronic kidney disease treated with haemodialysis: protocol for DIET-HD, a prospective multinational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e006897.

World Health Organisation Regional Office of Africa: Standard Operating Procedures For AFRO Strategic Health Operations Centre (AFRO SHOC). 2014.

El Ati J., Béji C., Farhat A., Haddad S., Cherif S., Trabelsi T., Danguir J., Gaigi S., Le Bihan G., Landais E. et al: Table de composition des aliments tunisiens; 2007.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Food composition Table for Use in Africa. WT Wu Leung, FAO, Rome, Italy; US Dept Health, Education, and Welfare, Bethesda 1968.

The French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occup Health Saf (ANSES): Ciqual French Food Composition Table version. 2016.

USDA. Foods list. In: National Nutrient Database for standard reference, 24; 2012.

Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4):1220S–8S. discussion 1229S–1231S

Rosner B, Willett WC. Interval estimates for correlation coefficients corrected for within-person variation: implications for study design and hypothesis testing. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(2):377–86.

Bartlett JW, Frost C. Reliability, repeatability and reproducibility: analysis of measurement errors in continuous variables. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31(4):466–75.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(2):135–60.

Shu XO, Yang G, Jin F, Liu D, Kushi L, Wen W, Gao YT, Zheng W. Validity and reproducibility of the food frequency questionnaire used in the shanghai Women's health study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(1):17–23.

Liu L, Wang PP, Roebothan B, Ryan A, Tucker CS, Colbourne J, Baker N, Cotterchio M, Yi Y, Sun G. Assessing the validity of a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) in the adult population of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Nutr J. 2013;12:49.

Jain MG, Rohan TE, Soskolne CL, Kreiger N. Calibration of the dietary questionnaire for the Canadian study of diet, Lifestyle and Health cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6(1):79–86.

Fumagalli F, Pontes Monteiro J, Sartorelli DS, Vieira MN, de Lourdes Pires Bianchi M. validation of a food frequency questionnaire for assessing dietary nutrients in Brazilian children 5 to 10 years of age. Nutrition. 2008;24(5):427–32.

Osowski JM, Beare T, Specker B. Validation of a food frequency questionnaire for assessment of calcium and bone-related nutrient intake in rural populations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(8):1349–55.

Sevak L, Mangtani P, McCormack V, Bhakta D, Kassam-Khamis T, dos Santos Silva I. Validation of a food frequency questionnaire to assess macro- and micro-nutrient intake among south Asians in the United Kingdom. Eur J Nutr. 2004;43(3):160–8.

Jackson M, Walker S, Cade J, Forrester T, Cruickshank JK, Wilks R. Reproducibility and validity of a quantitative food-frequency questionnaire among Jamaicans of African origin. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(5):971–80.

Jaceldo-Siegl K, Knutsen SF, Sabaté J, Beeson WL, Chan J, Herring RP, Butler TL, Haddad E, Bennett H, Montgomery S, et al. Validation of nutrient intake using an FFQ and repeated 24 h recalls in black and white subjects of the Adventist health Study-2 (AHS-2). Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(6):812–9.

Eck LH, Klesges RC, Hanson CL, Slawson D, Portis L, Lavasque ME. Measuring short-term dietary intake: development and testing of a 1-week food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991;91(8):940–5.

Cade J, Thompson R, Burley V, Warm D. Development, validation and utilisation of food-frequency questionnaires – a review. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(4):567–87.

Haftenberger M, Heuer T, Heidemann C, Kube F, Krems C, Mensink GB. Relative validation of a food frequency questionnaire for national health and nutrition monitoring. Nutr J. 2010;9:36.

Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Thompson FE, Byers T. Dietary assessment resource manual. J Nutr. 1994;124(11 Suppl):2245S–317S.

KomatsuI TR, OkuI SK, GimenoII SG, AsakuraIII L, CoelhoI L, Demézio d, SilvaIv CV, AkutsuV R, Sachs A. Validation of a quantitative food frequency questionnaire developed to under graduate students. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 2013;16(4):898–906.

Streppel MT, de Vries JH, Meijboom S, Beekman M, de Craen AJ, Slagboom PE, Feskens EJ. Relative validity of the food frequency questionnaire used to assess dietary intake in the Leiden longevity study. Nutr J. 2013;12:75.

van Dongen MC, Lentjes MA, Wijckmans NE, Dirckx C, Lemaître D, Achten W, Celis M, Sieri S, Arnout J, Buntinx F, et al. Validation of a food-frequency questionnaire for Flemish and Italian-native subjects in Belgium: the IMMIDIET study. Nutrition. 2011;27(3):302–9.

Malekshah AF, Kimiagar M, Saadatian-Elahi M, Pourshams A, Nouraie M, Goglani G, Hoshiarrad A, Sadatsafavi M, Golestan B, Yoonesi A, et al. Validity and reliability of a new food frequency questionnaire compared to 24 h recalls and biochemical measurements: pilot phase of Golestan cohort study of esophageal cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(8):971–7.

Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(10):1114–26.

Beaton GH, Milner J, McGuire V, Feather TE, Little JA. Source of variance in 24-hour dietary recall data: implications for nutrition study design and interpretation. Carbohydrate sources, vitamins, and minerals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;37(6):986–95.

Dehghan M, del Cerro S, Zhang X, Cuneo JM, Linetzky B, Diaz R, Merchant AT. Validation of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire for Argentinean adults. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37958.

Wang X, Sa R, Yan H. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire designed for residents in North China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17(4):629–34.

Cardoso MA, Tomita LY, Laguna EC. Assessing the validity of a food frequency questionnaire among low-income women in São Paulo, southeastern Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2010;26(11):2059–67.

Marchionil DML, Voci SM, Leite de Lima FE, Fisberg RM, Slater B. Reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire for adolescents. Cad Saúde Pública. 2007;23(9):2187–96.

Sue McPherson R, Hoelscher DM, Alexander M, Scanlon KS, Serdula MK. dietary assessment methods among school-aged children: validity and reliability. Prev Med. 2000;31(2):11–33.

Imaeda N, Goto C, Tokudome Y, Hirose K, Tajima K, Tokudome S. Reproducibility of a short food frequency questionnaire for Japanese general population. J Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):100–7.

Saglimbene VM, Wong G, Ruospo M, Palmer SC, Campbell K, Larsen VG, Natale P, Teixeira-Pinto A, Carrero JJ, Stenvinkel P, et al. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in adults on hemodialysis: the DIET-HD multinational cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2017;

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all subjects who participated in the study. We are also grateful to the GA2LEN Scientific Steering Committee for facilitating the GA2LEN FFQ and its methods as reference for our study. We also thank Dr. Inge Huybrechts, from Nutritional Epidemiology Group (NEP), International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization Lyon, France, for her pertinent remarks and comments to improve the manuscript during the drafting.

Funding

The validation study did not receive funding. All participants voluntarily agreed to take part.

Availability of data and materials

Under the policy of the University of Fez, data involving participants or patients working or attending the university hospital cannot be publicly shared. Individual requests for further information on the study can be sent to the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KE and VGL conceived the study idea, its design, and led the analyses and interpretation of the data. KR supervised the data collection. VGL wrote the final version of the manuscript. MK contributed to the conception and the design of the study. MMSD contributed to the conception of the study, and the acquisition of data. AB, AI, MMSD and MCB contributed to the study design and to the data collection. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was acquired from the Ethics Committee at University of Fez. All subjects were informed about their role in this study and gave written formal consent before being interviewed.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

El Kinany, K., Garcia-Larsen, V., Khalis, M. et al. Adaptation and validation of a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to assess dietary intake in Moroccan adults. Nutr J 17, 61 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-018-0368-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-018-0368-4