Abstract

Background

Although Plasmodium ovale is considered the cause of only mild malaria, a case of severe malaria due to P. ovale with acute respiratory distress syndrome is reported.

Case presentation

A 37-year old Caucasian man returning home from Angola was admitted for ovale malaria to the National Institute for Infectious Diseases Lazzaro Spallanzani in Rome, Italy. Two days after initiation of oral chloroquine treatment, an acute respiratory distress syndrome was diagnosed through chest X-ray and chest CT scan with intravenous contrast. Intravenous artesunate and oral doxycycline were started and he made a full recovery.

Conclusion

Ovale malaria is usually considered a tropical infectious disease associated with low morbidity and mortality. However, severe disease and death have occasionally been reported. In this case clinical failure of oral chloroquine treatment with clinical progression towards acute respiratory distress syndrome is described.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although Plasmodium ovale is considered the cause of only mild malaria, some reports indicate the potential evolution to severe disease and even death [1]. A case of severe ovale malaria with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) unresponsive to previous therapy with chloroquine is reported.

Case presentation

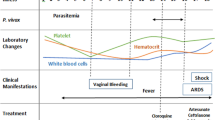

A 37-year old Caucasian man, with no co-morbidity, was admitted to the National Institute for Infectious Diseases Lazzaro Spallanzani in Rome, Italy, due to a 5-day history of fever (39 °C), headache and asthenia. Since 2013, he had been living in Angola without taking any anti-malaria chemoprophylaxis. On admission, the patient was in good condition; blood test showed only thrombocytopaenia (platelet count 63,000/mmc) with normal renal and liver function. Pan-malarial rapid test for malaria was negative while thick blood smear was positive and thin blood smear showed the presence of trophozoites and schizonts of P. ovale, with a 0.1% (5000/µl) parasitaemia. Oral chloroquine, 10 mg/kg as initial dose followed by 10 mg/kg on the second day and 5 mg/kg on the third day, was prescribed. In-house nested-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmed the diagnosis of P. ovale excluding mixed infections [2]. Plasmodium ovale wallikeri was identified by using a nested PCR followed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (a 245 bp band confirmed P. o. wallikeri) and verified with amplicon sequencing [3]. After 2 days of well-tolerated chloroquine treatment, the patient’s condition suddenly worsened: he developed dyspnoea at rest, cough with blood-tinged sputum and high fever (39.8 °C). Chest auscultation revealed bilateral crackles in both respiratory phases. Fluid balance (input–output) was negative. Respiratory rate was 37 breaths per minute, blood oxygen saturation was 92% under oxygen supplementation with 31% fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) Venturi mask, arterial blood gas showed an acute hypoxemia (PH: 7.45, PO2: 57 mmHg with an arterial oxygen tension (PaO2)/FiO2 ratio of 183) and serum albumin concentration was within normal ranges (3.9 g/dl). The patient had a persistent parasitaemia (0.1% parasitaemia) on chloroquine treatment (Fig. 3). PCR and serology for zika, chikungunya, dengue, and respiratory viruses, serology for Leishmania species, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Salmonella typhi and paratyphi, Rickettsia conorii and Treponema pallidum were all negative; urinary antigens of Legionella and Streptococcus pneumoniae were not detectable; blood and sputum cultures were negative. Posterior-anterior chest X-ray showed bilateral infiltrates (Fig. 1a) and chest computed tomography scan with intravenous contrast confirmed interstitial ground glass opacities involving upper and inferior right and left lobes with bilateral pleural effusion and cardiomegaly (Fig. 2). Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal heart function and ruled out cardiogenic oedema. Intravenous (iv) artesunate (2.4 mg/kg given twice daily at the first day then once daily), oral doxycycline (100 mg every 12 h), iv piperacillin/tazobactam (4.5 g every 8 h) and iv methylprednisolone (40 mg) were started. After 24-h artesunate treatment, parasite clearance was achieved and the patient’s condition improved (Fig. 3). Oral primaquine (30 mg daily for 14 days) was given. The patient was discharged in good clinical condition after 10 days of hospitalization. After 2 months, during the follow-up visit, a second chest X-ray was performed with unremarkable results (Fig. 1b) and no evidence of sequelae, relapse or haemolytic anaemia was reported.

Discussion and conclusion

Ovale malaria is usually considered a tropical infectious disease associated with low morbidity and mortality. However, severe disease and death have previously been reported [1].

In this case, clinical failure of oral chloroquine treatment in a patient with ovale malaria is described. Plasmodium ovale infection was confirmed by nested-PCR targeting the small sub-unit ribosomal RNA gene, detecting at least 10 parasite genomes per reaction and mixed infection with other Plasmodium spp were excluded [2]. Persistent P. ovale parasitaemia during the first 48 h of oral chloroquine therapy was associated with clinical progression towards ARDS. Only 1 day after the switch to iv artesunate, the parasitaemia clearance was reached and the patient’s condition improved. Chloroquine is commonly used for the treatment of P. ovale infection. In non-falciparum malaria, resistance to chloroquine is reported only for Plasmodium malariae whereas P. ovale is usually considered fully chloroquine susceptible [4].

Moreover, in a systematic review to determine the efficacy and safety of artemisinin-based combined therapy (ACT) for the treatment of non-falciparum malaria, ACT was considered at least equivalent to chloroquine in effectively treating non-falciparum malaria [5].

Recently, 2015 WHO guidelines on malaria treatment recommend either ACT or chloroquine, with high quality of evidence in the case of non-falciparum malaria [4]. Finally, ARDS is one of the severe complications of falciparum malaria but the pathogenesis is not yet well clarified; the inflammation and the increased endothelial permeability play an important role in ARDS. Moreover, iv overhydration, increased permeability of pulmonary capillaries, sequestration of red cells, and disseminated intravascular coagulation are all other likely determinants [6]. In this case overhydration was ruled out because of negative fluid balance. As previously reported in vivax malaria, the development of respiratory distress has been associated with an inflammatory response after treatment initiation [7]. Although chloroquine is known to have an anti-inflammatory modulation, inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 [8], in this case it did not seem to prevent the inflammatory phenomenon leading to respiratory distress. In a recent review, 22 cases of severe ovale malaria were identified and in 5 of them, ARDS was reported [9]. Epidemiological and clinical features of the 5 severe ovale malaria cases complicated by ARDS are summarized in Table 1. Nevertheless, in the 2015 WHO guidelines severe ovale malaria is not mentioned and consequently diagnostic criteria and treatment indications are lacking. Further studies are needed to better define the pathogenesis of severe malaria due to P. ovale and the relationship between its sub-species (wallikeri or curtisi) and the clinical manifestations. Finally, the occurrence of P. ovale chloroquine resistance and its molecular mechanisms should be investigated.

References

Lau YL, Lee WC, Tan LH, Kamarulzaman A, Syed Omar SF, Fong MY, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute renal failure from Plasmodium ovale infection with fatal outcome. Malar J. 2013;12:389.

Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, et al. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:315–20.

Oguike MC, Betson M, Burke M, Nolder D, Stothard JR, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri circulate simultaneously in African communities. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:677–83.

WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Visser BJ, Wieten RW, Kroon D, Nagel IM, Bélard S, van Vugt M, et al. Efficacy and safety of artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) for non-falciparum malaria: a systematic review. Malar J. 2014;13:463.

Taylor WR, Hanson J, Turner GD, White NJ, Dondrop AM. Respiratory manifestations of malaria. Chest. 2012;142:492–505.

Anstey NM, Handojo T, Pain MCF, Kenangalem E, Tjitra E, Prince RN, et al. Lung injury in vivax malaria: pathophysiological evidence for pulmonary vascular sequestration and posttreatment alveolar-capillary inflammation. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:589–96.

Jang C-H, Choi J-H, Byun M-S, Jue D-M. Chloroquine inhibits production of TNF-alpha, IL-1beta and IL-6 from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes/macrophages by different modes. Rheumatology (Oxf). 2006;45:703–10.

Groger M, Fischer HS, Veletzky L, Lalremruata A, Ramharter M. A systematic review of the clinical presentation, treatment and relapse characteristics of human Plasmodium ovale malaria. Malar J. 2017;16:112.

Hachimi MA, Hatim EA, Moudden MK, Elkartouti A, Errami M, Louzi L, et al. The acute respiratory distress syndrome in malaria: is it always the prerogative of Plasmodium falciparum? Rev Pneumol Clin. 2013;69:283–6.

Lahlou H, Benjelloun S, Khalloufi A, Moudden EL, Hachimi MA, Errami M, et al. An exceptional observation of acute respiratory distress associated with Plasmodium ovale infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50:A141.

Rojo-Marcos G, Cuadros-González J, Mesa-Latorre JM, Culebras-López AM, de Pablo-Sánchez R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in a case of Plasmodium ovale malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:391–3.

Rozé B, Lambert Y, Gelin E, Geffroy F, Hutin P. Plasmodium ovale malaria severity (in French). Med Mal Infect. 2011;41:216–7.

Authors’ contributions

DA, GTS and MI performed the clinical assessments, treated the patient and drafted the manuscript. SL, OA and CA performed the clinical assessments and treatment, searched the literature and drafted the manuscript. PMG performed molecular diagnostic tests and drafted the manuscript. DA and NE performed literature search, drafted and completed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board approval is not required by the Ethical Committee of the authors’ institution for the presentation of a single case report.

Funding

Publication of this report was supported by Ricerca Corrente and Ricerca finalizzata WFR PE-2013-02357936 funded by the Italian Ministry of Health.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

D’Abramo, A., Gebremeskel Tekle, S., Iannetta, M. et al. Severe Plasmodium ovale malaria complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome in a young Caucasian man. Malar J 17, 139 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2289-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2289-2