Abstract

Multi resistant fungi are on the rise, and our arsenal compounds are limited to few choices in the market such as polyenes, pyrimidine analogs, azoles, allylamines, and echinocandins. Although each of these drugs featured a unique mechanism, antifungal resistant strains did emerge and continued to arise against them worldwide. Moreover, the genetic variation between fungi and their host humans is small, which leads to significant challenges in new antifungal drug discovery. Endophytes are still an underexplored source of bioactive secondary metabolites. Many studies were conducted to isolate and screen endophytic pure compounds with efficacy against resistant yeasts and fungi; especially, Candida albicans, C. auris, Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus, which encouraged writing this review to critically analyze the chemical nature, potency, and fungal source of the isolated endophytic compounds as well as their novelty features and SAR when possible. Herein, we report a comprehensive list of around 320 assayed antifungal compounds against Candida albicans, C. auris, Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus in the period 1980–2024, the majority of which were isolated from fungi of orders Eurotiales and Hypocreales associated with terrestrial plants, probably due to the ease of laboratory cultivation of these strains. 46% of the reviewed compounds were active against C. albicans, 23% against C. neoformans, 29% against A. fumigatus and only 2% against C. auris. Coculturing was proved to be an effective technique to induce cryptic metabolites absent in other axenic cultures or host extract cultures, with Irperide as the most promising compounds MIC value 1 μg/mL. C. auris was susceptible to only persephacin and rubiginosin C. The latter showed potent inhibition against this recalcitrant strain in a non-fungicide way, which unveils the potential of fungal biofilm inhibition. Further development of culturing techniques and activation of silent metabolic pathways would be favorable to inspire the search for novel bioactive antifungals.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antifungal resistance was underestimated for a long period of time. The most pronounced cases were seen in patients with cancer therapy, organ, or bone marrow transplantation. Currently, a huge deficiency is encountered in the market regarding the antifungal drugs effective against systemic and local infections; particularly, with the emerging multi-resistant fungal strains [1]. The WHO report in 2023 listed three fungal priority pathogens, Candida auris, Aspergillus fumigatus and Cryptococcus neoformans and urged the critical importance of developing new effective drugs against them [2].

Endophytes are the microbial community associated with plants with no significant harm, which was known to provide the plant with marked natural products diversity as well as disease, insects, nematodes defiance [3, 4]. These largely untapped and sustainable resources of natural products have revolutionized the field of drug discovery since it provided novel molecular skeletons in mass yield [5, 6]. It is estimated that endophytes repository of bioactive molecules (80%), particularly the novel ones, could exceed those reported from soil microorganisms; hence, exploring endophytes is an outstanding approach to fight antifungal resistance [6].

Despite the ubiquitousness of Aspergillus spores everywhere and the fact that most people can inhale them without hazard, those with severe respiratory infections, hospitalized or under chemotherapeutic regimens can be extremely vulnerable to them. Aspergillosis is life threatening in patients with underlying diseases or immunocompromised patients and is the most common missed diagnosis in intensive care units [7]. With the development of antifungal resistance, A. fumigatus became on the watch list in the CDC antibiotic resistant threats 2023; especially, its azole resistant strains whose infection is 33% less likely to be treated than other Aspergillus strains [8]. Azole resistance can be acquired from the environment without prior exposure to azole fungicides triazole, voriconazole and itraconazole are antifungal agents that remained in the market for a long time effective, cheap and available yet the emergence of resistance has given the problem new dimensions and demanded the discovery of potent alternatives [9].

Another fungi on the list was C. neoformans, representing an annual 1 million infections, and commenced with inhaling the fungal air-borne spores and progressed to pneumonia and even CNS meningitis, a cryptococcosis scenario that was commonly encountered in immunocompromised patients with organ transplantation, cancer or HIV [10]. With only a few limited choices of antifungal treatments like fluconazole., amphotericin B or 5-fluorocytosine whose costs, toxicity and cost deter their prescription in the first place let alone azole resistance, Cryptococcus sp. are largely left untreated with a huge health hazard [11]. C. auris emerged recently as a major infection in intensive care units (ICUs) in reports in India, Kuwait and Spain with average 25 days stay patients. Even though C. auris isolates appeared to colonize indwelling devise and catheters, they also infected skin and different body sites [12]. This review aims to cover the antifungal activity exerted by endophytic compounds and extracts against three of the WHO top priority pathogens, A. fumigatus, C. neoformans and Candida species C. auris and C. albicans. Details about the endophyte source, collection, culture, compounds chemistry and biosynthesis, SAR and antifungal properties will be discussed and analyzed. Aspergillus diseases were controlled by commonly prescribed azole antifungal agents until recently when azole resistant A. fumigatus emerged as a worldwide health threat. Previously effective medications fell short of dealing with this antifungal resistance, which necessitated antifungal drug discovery research. Natural products with MIC values < 10 μg/mL are considered potent and should be given due care to progress with their in-vivo and clinical studies. MIC values between 10 and 100 μg/mL are moderately active and may be further promoted if suitable medicinal chemistry modifications can enhance their efficacy [13].

Methodology

Papers with reported bioactivity against any of these pathogenic strains, A. fumigatus, C. neoformans, C. albicans or C. auris were included. Endophytes of either fungi, actinomycetes or bacteria were included. The literature search period started from 1980 and extended to 2024, and all types of publications, original articles, reviews or reports and commentaries were included. Negative results of antimicrobial assays against any of the strains of interest were listed here and analyzed to help direct future research to study promising compounds only. Boolean search operators like and, or, not, near, * were exploited to narrow down the search items for the best fit of our keywords. Search engines like Web of Science, Reaxys, Scopus, Google Scholar, Pubmed and Science direct were utilized. Phrase and keywords used were C. auris antifungal (1099 results), C. albicans antifungal (18,297 results), A. fumigatus antifungal endophytes (4958 results), Cryptococcus neoformans antifungal endophytes (24 results), bioactive compounds endophytes C. auris (307 results), bioactive compounds endophytes C. albicans (12,900 results), bioactive compounds endophytes A. fumigatus (8320 results), bioactive compounds endophytes Cryptococcus neoformans (2750 results). The total number of initial search results was 48,655, which was narrowed further to 110 articles. Results were refined to only the English language articles in top peer reviewed journals, and highly cited articles were prioritized. All articles filtration criteria were conducted according to the Web of Science (WOS) core collection selection.

A. Terrestrial plant-endophytes

I. Bacterial endophytes with activity against selected pathogens

The moderately active antifungal agent toxoflavin was isolated from Lycoris aurea bacterial endophyte and optimized in large scale fermentation to yield more than 1300 mg/litre; additionally, the azole resistant human pathogen A. fumigatus and C. neoformans were susceptible to toxoflavin [13]. The bacterial endophyte Bacillus velezensis LDO2 isolated from peanut was active against A. flavus mycelial growth 80.77%, and this was related to the fungicidal compounds fengycin, bacilysin, and surfactin indicated in the UPLC-MS analysis [14].

Three Bacillus strains, B. cereus (LBL6), B. thuringiensis (SBL3) and B. anthracis (SBL4) were isolated from Berberis lyceum, and their ethyl acetate extract displayed activity against A. niger and A. flavus [15]. Bacterial endophytes colonizing the same biological niche with fungi possibly produce metabolites to antagonize and hinder their growth. This was seen in many cases as in cannabis seedling endophytes, which possessed antibiotic activity against its Aspergillus pathogen as well as Alternaria, Penicillium, and Fusarium sp. Isolation of the bioactive metabolites is highly urged here to progress into discovery and optimization of potential antifungal molecules [16]. In the same vein, B. velezensis isolated from grapevine were protective against other grapevine-endophytic fungi including Aspergillus spp. Evidently, several lytic enzymes were revealed using molecular genome mining tools as proteases, cellulases and chitinases as well as functional genes encoding macrolactin, fengycin, iturins, difficidin, and mycosubtilin secondary metabolites, which were shown by PCR analysis [17].

II. Fungal endophytes with activity against selected pathogens

1. Terpenes

On the other side, monoterpenes from the endophytic Pestalotiopsis foedan were only weakly active with MIC value of 50 μg/mL [18]. Nicotiana tabacum endophytes produced several molecules, a fumagillol derivative, a 10-membered lactone, a cyclohexanones together with sesquiterpenes and cembrdiene diterpenes with promising antifungal affect against A. fumigatus and MICs ≤ 8 μg/mL [19] (Table 1). (S, Z)-phenguignardic acid methyl ester, a meroterpene of the guignardianone type was isolated from the endophyte Phyllosticta sp J13-2-12Y and manifested a potent effect against C. albicans. These meroterpenes are rare in nature and comprised of an amino acid derived benzylidene dioxolanone while the guignardone type compounds formed of a monoterpene linked to a C-7 carbon unit were devoid of considerable activity [20]. Monoterpenes of the Pestalotiopsis endophytic isolate from Dendrobium officinale of Yandang Mountain in China possessed significant antifungal effect against C. albicans, C. neoformans, T. rubrum, and A. fumigatus [21]. The triterpene glycoside enfumafungin was isolated from some type of Kabatina species inhabiting the leaves of Juniperus communis with an activity towards A. fumigatus resembling the approved fungicide caspofungin acetate and its precursor pneumocandin B0. In-vivo studies in rats challenged with C. albicans to cause candidemia recorded moderate activity with ED90 of 90 mg/Kg with morphological alternations suggesting cell wall targeting particularly glucan synthase [22] (Fig. 1). Further chemical modifications and bioavailability studies led to the development of ibrexafungerp with better pharmacokinetics than enfumafungin [23, 24]. Another member of this class of metabolite is arundifungin, which was isolated from Arthrinium arundinis and showed glucan synthase inhibitory activity comparable to echinocandin L-733560 and papulacandins, yet the activity was specific to A. fumigatus and C. albicans and not Cryptococcus. This was rationalized to be due to the presence of 1,6-β-glucan or other non-1, 3-β-d-glucan components in its cell wall [25].

2. Alkaloids

Cochliodinol was isolated from the endophyte Chaetomium globosum SNB-GTC2114 and demonstrated anticandidal effect of 2 μg/mL as well as potent cytotoxicity with IC50 as low as 0.53 μM in cell lines KB, MRC5, and MDA-MB-435 [26]. Cochliodinol is a prenylated dimeric indole alkaloid first described in 1975 by Brewer et al. and isolated later from several Chaetomium species [27]. The pyridine derivatives penicolinates A–C isolated from Penicillium sp. BCC16054 showed moderate activity against C. albicans compared to amphotericin B whose IC50 value of 0.072 μg/mL. Despite their antimalarial and antitubercular effects, they manifested cytotoxicity against NCI-H187, MCF-7, KB, and the normal VERO cell lines, which might retard the progress of these molecules to the clinical use [28]. The benzophenone asperfumoid and indole bioactive mycotoxin alkaloids were isolated from Cynodon dactylon endophytes and revealed marked anti-candidal activity. Helvolic acid and physcion fermentations were optimized to provide large scale cultures with an activity in the range of MIC 31-125 μg/mL [29] (Fig. 2). Hypoxylon species from Cinnamomum cassia Presl biosynthesized three furanones and three pyrrolo-pyrazines with hypoxylonone C and (3S,8aS)-3-benzyloctahydropyrrolo[1,2-α]pyrazine-1,4-dione exerting a marked anticandidal effect [30]. Indole alkaloids with notable activity against C. albicans were isolated from Chaetomium sp. SYP-F7950 endophyte with MIC range of 0.12 to 9.6 μg/mL although not devoid of cytotoxicity in A549 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines [31].

3. Peptides

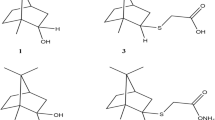

Among the few effective antifungal molecules towards C. auris is persephacin, which was isolated from some plant-endophytes. This cyclic peptide was described as an aureobasidin like structure devoid of phenylalanine but possessing persephanine as an unusual amino acid. Persephacin exerted a significant activity against fluconazole-resistant C. albicans and A. fumigatus causing eye infection in an ex-vivo study, which outperformed control drugs [32] (Fig. 3). Moreover, the 3D tissue models, highly simulating in-vivo studies, demonstrated its safety for treatment of eye infection with negligible irritation or toxicity [32].

Around four-hundred endophytes of Eugenia bimarginata DC were isolated and examined for their antifungal efficacy against Crypotcoccus neoformans and gattii, which resulted in discovering Mycosphaerella sp. UFMGCB 2032 extract with MIC values of 31.2 μg/mL and 7.8 μg/mL [33]. Upon inspecting its two major compounds, the eicosenoic acid derivative possessed an extra double bond, which was believed to alter the Log P value and alter receptor interaction. Myriocin reduced fungal virulence by stimulating the production of Cryptococcal pseudo hyphae, and both compounds showed synergistic effect with amphotericin B and might induce apoptotic cell death in fungi [11]. Coronamycin, the complex mixture of bioactive peptides was effective with a lower MIC value than flucytosine against C. neoformans, yet it exhibited negligible activity towards several fungal strains as A. fumigatus, A. ochraceus, Fusarium solani, Rhizoctonia solani and Candida species as C. parapsilosis (ATCC 90018), C. krusei (ATCC 6258), C. tropicalis (ATCC 750) except C. albicans (ATCC 90028) [34]. A cyclodepsipeptide comprised of six amino acids and a long chain fatty acid was isolated from Fusarium sp. inhabiting the roots of Mentha longifolia and displayed potent antifungal effects against three Candida species as well A. fumigatus. The antimalarial activity was pronounced against P. falciparum (D6 clone) with MIC value of 0.34 μM; however, its cytotoxicity in cell lines L5178Y and PC12 might hinder further progression [35].

4. Amides

The amino benzamide derivatives, fusarithioamide B and A [36]. manifested potent activity C. albicans compared to the standard antifungal clotrimazole, but their selective cytotoxicity against KB, HCT-116, BT-549, SKOV-3, SK-MEL, and MCF-7 cell lines might require chemical optimization to be suitable for further in-vivo and clinical studies. The proposed mode of action is possibly due to their sulphur-based structure reported before to react with SH-moieties in bacterial and microbial proteins and disrupting their metabolism [37]. Of the three isolated decatriene fatty acid amides, only bipolamide B was moderately active with broad spectrum against several fungal cells. The structural resemblance allowed prospecting a role of the five membered carbon short chain in bipolamide A to control toxicity/activity ratio since it was completely ineffective [38].

5. Polyketides

The second was koninginins X–Z polyketides from Trichoderma koningiopsis SC-5 with no demonstrated activity up to 100 μg/mL against C. albicans [39]. The endophytic fungus Aspergillus sp. AP5 isolated from Phragmites australis was chemically profiled to unveil the antifungal activity of its ethyl acetate crude extract towards C. albicans ATCC 10231 and A. niger. Nafuredin, carbonarin A and I, and yanuthone D were detected by HR-LCMS and prospected to be the bioactive antifungal ingredients according to PASS software of molecular networking [40]. Pestafolide A, the reduced azaphilone derivative isolated from the endophyte Pestalotiopsis foedan in China showed activity against Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 10894). This azaphilone structure partially resembled decipinin A [41] in the two spiro connected pyran rings and resembled monascusone A [42] in its partial tetrahydroisochromenone moiety, yet monascusone A lacked the C-9 tetrahydropyran. Other isobenzofuranones were isolated as pestaphthalides A and B, closely related to acetophthalidin [43], with antifungal effect against Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) and Geotrichum candidum (AS2.498), respectively (Table 1) [44]. Pestaphthalides A and B were totally synthesized before through iridium-aryl borylation followed by a Suzuki-cross coupling/Jacobsen-epoxidation, epoxide opening and a rearrangement of cyclic carbonate/γ-lactone [45]. Biosynthetically, azaphilones originate from a NR-PKS polyketide and fatty acid pathway combination occasionally involving amino acids [46]. Pestalofones are derived from a terpenoid/polyketide pathway with structural similarity to iso-A8277C isolated before from the endophyte Pestalotiopsis fici [47, 48]. Pestalofones B and C originated from the Diels–Alder reaction of two molecules of iso-A82775C with a characteristic polyhydroxylated cyclohexane ring either spiro connected or via exocyclic methylene. A. fumigatus (ATCC 10894) was susceptible to pestalofones C and E with MIC values of 1.10 and 0.90 μM, respectively [49]. The NRPS/PKS biosynthesized occidiofungin obtained from the soyabean endophyte Burkholderia sp. MS455 inhibited the growth of A. flavus by stimulating apoptotic cell death [50]. Occidofungin demonstrated a potent antifungal activity against several Candida clinical isolates including those with fluconazole and caspofungin resistance. According to the time-kill and PAFE assays, the target of occidiofungin was presumably different from caspofungin and echinocandin. Furthermore, it showed gastric acid and temperature stabilities, which predispose its possible suitability for oral route administration than caspofungin after conducting bioavailability studies. With only azoles till now as the approved oral antifungal agents, in-depth studies of occidofungin are highly warranted [51]. More polyketides phomopoxides of the cyclohexenoid polyhydroxylated type were isolated from the Phomopsis sp. YE325 endophyte with unique stereochemical and oxygenation patterns. Similar hexenoids were reported from Streptomyces, Eupenicillium and Aspergillus before [52]. Phomopoxides B, D and G revealed a significant antifungal activity against C. albicans and A. niger [53]. Among a large-scale library, isolated from Pestalotiopsis sp., comprised of caprolactams, polyketides, quinones, and polamides only 2-hydroxy-6-methyl-8-methoxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-1-carboxylic acid reported a weak anticryptococcal activity of 50 μM [54]. Comparable to nystatin, CR377 represented a potent selective anticandidal molecule [55]. CR377 was first isolated from unidentified Fusraium sp. and later obtained from Fusarium fujikuroi by Von Bargen et al. who identified the genetic cluster and renamed it as fujikurin A [56]. Aplojaveediins A isolated from the endophyte Aplosporella javeedii exhibited antifungal effect 100 μM when tested against C. albicans ATCC 24433 hyphal forms and Saccharomyces cerevisiae while being non-cytotoxic towards cancer cell lines HUH7, THP-1, and CLS-54. Additionally, it showed a fungicidal activity and a fast viability decline when given in a fourfold MIC value compared to hygromycin, which only exerted a static growth inhibitory effect [57].

Halogenated fungal derived compounds were not subjected to sufficient scrutinization as antifungal agents, and few reports stated their dominant sources from marines, sponges and algae. Moreover, questions remained unanswered about their enzymatic or non-enzymatic biosynthesis to better manipulate this potential source of underexplored compounds [58]. In a recent study, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors as suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid were employed to enhance the isocoumarin biosynthetic pathways in Lachnum palmae and resulted in the production of brominated and chlorinated products with moderate activity against B. cereus and S. aureus although with insignificant effect against C. albicans and C. neoformans. Zhao et al. noted the higher activity of the brominated molecules compared to the chlorinated one [59]. In accordance with the host plant activity, the fungal endophyte Botryosphaeria rhodian yielded the depsidones Botryorhodines A and B. Both the compounds and the crude extract manifested potency against A. terreus human pathogen, possibly attributed to the aldehydic group of C-3 position. Depsidones from natural products were reported typically from lichens and few were found in plants or endophytes [60]. The previously synthesized 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin was obtained in decent amounts from the endophytic Xylaria sp. YX-28 residing in an ancient 1000-year-old Ginkgo tree. The abundance and large-scale production of this wide spectrum antimicrobial and antifungal agent warranted more exploitation; especially for priority pathogens as C. albicans and A. niger [48]. The rare in nature macrolactone glycoside Lecythomycin exerted a moderate inhibitory but selective effect towards the growth of A. fumigatus and C. kruzei since it manifested no similar action on closely relevant strains as C. albicans and A. faecalis or bacteria. This was credited to its uncommon 24-membered lactone and the mannoside sugar part, only ascribed to few fungi before [61]. The isocoumarin cladosporin obtained in high titer amount of 24% from Cladosporium cladosporioides was shown to be active against Plasmodium falciparum in the nanomolar range and against Cryptococcus neoformans. The chemical features of cladosporin were analyzed to highlight the importance of the open unsubstituted 5′-position, C-6’ R configuration, and C-6 hydroxylation for the antifungal activity [62]. Depsidones as simplicildone C was isolated from Simplicillium sp. PSU-H4 in Thailand and displayed a weak antifungal effect against C. neoformans with a high safety profile towards VERO cell lines, which suggested the need to improve this depsidone nucleus and enhance its potency by medicinal chemists [60, 63]. In the same way, simplicildones K and globosuxanthone E produced by Simplicillium lanosoniveum were active against Cryptococcus neoformans ATCC90113 with the MIC value of 32 μg/mL [64]. Both the polar and nonpolar fractions of the endophytic fungus extract P. sclerotiorum PSU-A13 manifested good antimicrobial and anti-HIV integrase activities. Contrarily to what might be considered, the assays conducted on three azaphilone acetonide, deacetonide and isocoumarin nuclei showed the significance of the chlorine atom in the sclerotiorin isolated from the hexane extract for both the antifungal and anti-HIV effects, irrespective of the azaphilone unit [65] (Fig. 4). The novel skeleton of spiro 5, 6 membered lactones revealed remarkable antifungal effect against both C. albicans and C. neoformans with MIC80 values down to 2 and 4 μg/mL, respectively. For instance, spiromassaritone isolated from Rehmannia glutinosa endophytes was more potent than griseofulvin by 3 folds magnitude [66]. Dimeric chromanones showed potent effect against C. albicans ATCC 10231 with paecilins A the most active among its congeners. Similarly, strain Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was inhibited by paecilins L and N with MIC values of 16 μg/mL for each, and Salmonella enteritidis ATCC 25923 were susceptible to chromanones paecilins L and N with MIC values 32 μg/mL for each [67]. The crude endophytic extract of A. tubingensis AN103 demonstrated higher antifungal effect than its pure compounds with MIC values between 3.2 and 14 μg/mL against F. solani MLBM227, A. niger ATCC 16404, C. albicans ATCC 10231, and A. alternata MLBM09. These compounds were the naptha-γ-pyrones pyranonigrin A, TMC 256 A1 as well as fonsecin and asperazine [68].

6. Fatty acid derivatives

Candida albicans infections were characterized as serious health threats with more than three hundred thousand infected cases reported per year. Women suffer from vulvovaginal candidiasis, which is a recurrent infection and at least once in life 75% of females encountered it. Immunocompromised patients are particularly vulnerable where mortality rate can reach up to 50% even with drug treatment [69]. In two attempts to study endophytes from food sources in China, tee tree endophyte Scopulariopsis candelabrum was fermented in large scale to obtain monomers and dimers of alkenoic acids namely, hymeglusin and fusariumesters, and the former showed anticandidal activity with MIC 20 μg/mL [70]. From rare liverworts as Scapania verrucosa Heeg, which are difficult to obtain in large amounts, endophytes represent a promising way to study secondary metabolites due to their high biomass production. For example, Chaetomium fusiforme was isolated from S. verrucosa and produced several volatile molecules, mainly methyl ester (21.25%), acetic acid (35.05%), 3-methyl-, and butane-2, 3-diol (12.24%), and valeric acid, possibly causing its effect against Candida albicans ATCC76615, Cryptococcus neoformans ATCC32609, Trichophyton rubrum, and Aspergillus fumigatus with IC80 values of 32, 64,64 and 8 μg/mL, respectively [71].

7. Miscellaneous

Several ascomycetes endophytic fungi were isolated from family Cupressaceae hosts as Cupressus, Platycladus, and Juniperus species in Iran and revealed anti-aspergillosis activity against human pathogenic Aspergillus fumigatus IFRC460 and Aspergillus niger IFRC278 through Petri dish dual-culture assays. The aryl ethers aspergillethers A and B were isolated from a Pulicaria crispa Forssk endophyte and reported significant activity against C. albicans and Geotrichium candidum [72, 73]. A diphenyl ether namely, 4-dihydroxy-2′, 6-diacetoxy-3′-methoxy-5′-methyl-diphenyl ether was isolated from Verticillium sp. and showed significant antifungal effect against C. albicans and A. fumigatus but not Cryptococcus neoformans [74]. Mycorrhizin A was first isolated from a mycorrhizal fungus of Monotropa hypopitys L. [75], and several attempts of synthesis were conducted before its complete synthesis in 1982 [76]. This benzofuran reported broad spectrum antimicrobial effect with a moderate activity towards C. albicans [77]. Mycosphaerella sp was isolated from Eugenia bimarginata and provided two usnic acid derivatives, mycousfuranine and mycousnicdiol, displaying moderate activity against Crypotcoccus neoformans and gattii 50 and 250 μg/mL [78] (Figs. 5 and 6).

8. Endophytic bioactive extracts

The endophyte Epicoccum nigrum isolated from the roots of Maxillaria rigida was in a study among more than 383 isolated endophytes in Brazil and displayed activity against both C. albicans and C. krusei with MIC values of 7.8 μg/mL. No further work was done to investigate the extract and isolate the bioactive components [79]. The fungal isolates obtained from several arid plant species cultivated in Andalusia were examined for their secondary metabolite production, which was enhanced using polymeric resins such as Amberlite® and Diaion®. For instance, calbistrin A, dextrusin B4, and secalonic acid C were produced exclusively in presence of XAD-16 resin from Psudocamarosporium sp., Alternaria sp. and Sclerostagonospora sp. CF-281856, respectively. About 61 fungal extracts reported 70% inhibition of A. fumigatus ATCC 46645, and 23 fungal strains were effective against Candida albicans MY1055 [80] (Fig. 7). The amazonian plant Arrabidaea chica was the source of more than 100 endophytes whose ethyl acetate extracts were active against different microbial strains. The most active was Botryosphaeria mamane CF2-13 extract against P. mirabilis, E. coli, S. enterica, S. epidermidis, B. subtilis, S. marcescens,, A. brasiliensis,, C. tropicalis, K. pneumoniae, C. albicans, S. aureus and C. parapsilosis with MIC values in the range of 0.3 mg/mL [81]. The endophytes from Monarda citriodora Cerv. ex. Lag extended the antifungal effect of its host plant and showed biocontrol ability and complete inhibition against strains Sclerotinia sp., Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus and Colletotrichum capsica using dual culture assays with 50% inhibition ranging between 54 and 100% [82]. Four endophytic strains isolated from Dendrobium devonianum and D. thyrsiflorum cultivated in Vietman demonstrated weak antifungal effect towards A. fumigatus and C. albicans using agar diffusion assay [83]. More than nine ginkgo endophyte extracts proved potency against C. albicans, and A. fumigatus Trichophyton rubrum, and Cryptococcus neoformans and as antioxidants when tested by DPPH assay [84]. From the orchids trees Dendrobium devonianum and D. thyrsiflorum, more than 25 endophytic isolates were purified and identified based on ITS sequencing, and Fusarium, Epicoccum, and Phoma species were the dominant strains from both roots and stems, yet none exerted notable effect upon C. neoformans despite pronounced antibacterial effect against Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus [83]. 44.8% of endophytes of Pseudolarix kaempferi were screened against Pyricularia oryzae P-2b model and exhibited activity towards Cryptococcus neoformans, Trichophyton rubrum, and Candida albicans demonstrated by either conidia inhibition, swelling of hyphae or beads formation [85]. Moreover, the VOCs of family Cupressaceae endophytes showed time dependent inhibition of A. niger and A. fumigatus fungal growth in less than a week. The most active of which were Trichoderma koningii CSE32 and T. atroviride JCE33 extracts [7].

9. Mode of action of antifungal natural products

Unlike antibacterial compounds, many of the tested antifungal molecules are still far from being deeply studied to illustrate their exact mode of action, yet some mechanistic views were presented regarding terpenoids as follows. Fungal cell wall components include polymers such as chitin, mannoproteins, sphingolipids and glucans. While glucans are dominated by 1,3 or 1,6-glucose polymers in the cell wall, ergosterol constitutes the cell membrane. Inhibition of these polymers results in cellular death [86]. Many natural products act by crossing fungal cell walls and accumulating inside the lipid bilayer. This is true for terpenes/terpenoids whose lipophilicity enhance their capacity to go into the cell membrane and either lead to cell death or lack of germination [87]. Terpenes were reported to act by suppressing energy generation through mitochondrial damage. This alters virulence functions, cell wall protection and ergosterol biosynthesis, which is essential for fungal integrity [88]. Change in membrane hyperpolarization affects permeability and ions as calcium, pumps, and ATP pool eventually leading to cellular apoptosis. These events can be assessed by evaluating mitochondrial membrane permeability (MMP) and the amount of H + pumped out of the mitochondrial matrix [89]. A major fungal strategy to develop resistance is through efflux pumps, which remove substances out of the cell and undermine the effect of accumulated antifungal agents [90]. Many terpenes can act by inhibiting efflux pumps to cut down fungal resistance by down-regulating genes coding for efflux pumps as CDR1 and CDR2. Drimenol and other drimane sesquiterpenes were isolated from genus Termitomyces were screened against C. albicans and fluconazole resistant strains of C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. albicans, C. krusei, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus and C. auris revealed potent microbicidal effect with MIC value of drimenol was investigated further and showed a fungal cell, membrane damaging effect. Further studies with mutant spot assay manifested changes in pathways and genes as the Crk1 kinase associated gene products, orf19.759, orf19.1672, Ret2, Cdc37, and orf19.4382 [91]. This was further assisted with heterozygous barcoded mutant collection assay, which was conducted on both Saccharomyces cervesise and C. albicans to unveil the target genes and complemented with molecular docking [92].

III. Actinomycete endophytes with activity against selected pathogens

Streptomyces YHLB-L-2 was isolated among 269 endophytes from medicinal plants in Fenghuang Mountain and its yeast peptone media fermentation produced quinomycin A, which was active against Cryptococcus neoformans and clinical resistant strains of Aspergillus fumigatus [93]. Endophytic Streptomyces in Arnica montana L. produced the cycloheximide with anticandidal effect against C. parapsilosis, presumably produced for the benefit of the host plant as antifungal and antiviral [94]. Streptomyces endophyte from roots of wheat plant hindered the growth of Aspergillus niger MTCC 282, despite showing no chitinase production, which indicated that its secondary metabolites could elicit the antifungal effect [95]. As many other Streptomyces strains, Streptomyces sp. K-R1 associated with root of Abutilon indicum produced the anthranilic peptide actinomycin D, yet it revealed crude extract weak activity towards fluconazole resistant Candida albicans MTCC-183 and Aspergillus niger MTCC-872 with MIC 1 mg/mL [96].

B. Marine-derived endophytes with activity against selected pathogens

Bostrycin and its deoxy derivative were isolated from the marine endophyte Nigrospora 1403 and reported moderate activity towards C. albicans, yet they were both of potent cytotoxic potential. The MTT assay of bostrycin suppressed the growth of six cancer cell lines, MCF-7, Hep-2, A549 Hep G2, KB, and MCF-7/Adr with IC50 values of, 6.13, 5.39, 2.64, 5.90, 4.19, and 6.68 μg/mL, respectively. Similarly, deoxybostrycin inhibited the growth of all tumor cells with IC50 between 2.4 and 5.4 μg/mL [97]. The marine macroalgae in bay of fundy in Canada provided about seventy-nine different endophytic species isolated from ten hosts. Among them were Penicillium sp, Helicomyces sp., Aspergillus sp., Botrytis sp., Trametes versicolor, Coniothyrium sp., Cladosporium sp., Coelomycete I, Hypoxylon sp., and Botryotinia fuckeliana. The mycelial and media methanol extracts displayed significant activity against C. albicans, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus [98]. Polyketides of the tandykusin type as well as phenyl derivatives were isolated from the mangrove endophyte Trichoderma lentiforme ML-P8-2 and exerted a moderate effect against C. albicans [99]. The sesquiterpene tremulenolide A was isolated from the endophyte Flavodon flavus PSU-MA201 together with a rare yet inactive difuranyl methane. Tremulenolide A was mildly active against C. neoformans [100] (Fig. 8). Heterodimeric xanthones with a 7,7′-Linkage were isolated from the mangrove plant endophyte Aspergillus flavus QQYZ. The non-biaryl linkage was reported for the first time in xanthones and possibly played a pronounced role in the broad-spectrum antifungal effect of aflaxanthone A and B. Other endophytic xanthones with C3-N-C2′ bridge like incarxanthone F [101], 2,2′-biaryl bond like phomoxanthones C–E [102], 2-4′-linkage like penicillixanthone B [103] or 4,4′-linkage like deacetylphomoxanthone C [104] were recorded before from Peniophora incarnata, Phomopsis sp. xy21, Setophoma terrestris (MSX45109), Phomopsis sp. HNY29-2B, respectively, but showed no activity against fungi [105]. From an unidentified endophytic fungus in Costa Rica, khafrefungin was separated and found effective against both filamentous fungi and yeasts; particularly, C. albicans, C. neoformans with MFC of 4 and 4 mg/mL respectively. In this scenario, complex sphingolipids were lost with the inhibition of phosphoinositol transfer to ceramides [106]. Khafrefungin specifically hindered inositol phospho-ceramide (IPC) synthase without inhibiting mammalian sphingolipid synthesis, which added to its safety profile.

C. Coculture techniques of endophytes with activity against selected pathogens

Under standard fermentation procedures, microbial chemical diversity is usually limited, and the rediscovery of known metabolites becomes a common scenario, which delays novel molecules drug discovery [107]. Coupled with the large number of uncultivable strains, already existing in environment but not accessible to research, the use of different fermentation strategies to unlock the power of cryptic metabolites seems mandatory. For example, one strain many compounds (OSMAC)technique where a single promising microbial strain is subjected to different media and culturing conditions to maximize its production of bioactive molecules. Another example is epigenetic methods and employing modifiers like DNA methyl transferase inhibitors or histone deacetylase inhibitors to manipulate genetic clusters and possibly activate the transcription of secondary metabolite silent genes. Lastly, coculturing where the metabolites of one strain can induce the expression of another strain metabolites [108]. It is worth mentioning that coculturing strategies are usually straightforward and effective with no need for genetic level operations. In this section, data will be presented about how cocultures inspired the discovery of antifungal molecules against WHO priority pathogens [109].

The coculture of Cophinforma mamane with C.albicans shed light on the nature of interaction between the two microbes, particularly, by applying untargeted metabolomics and UPLC-MS–MS analysis to identify the compounds produced in both the axenic and coculture conditions. Results unveiled the downregulation of key survival metabolites of C. albicans like myoinositol, C20 sphinganine 1-phosphate, farnesol, and gamma-undecalactone; therefore, explaining the antifungal potential of the endophyte crude extract [110]. The endophyte Acremonium zeae was isolated from maize plant and showed through paired culturing an antifungal potential against A. flavus and F. verticillioides, possibly due to a significant production of pyrrocidine antibiotic [111] (Fig. 9). In a study of Nicotiana tabacum L. (No. Y20210917) with its associated four endophytic fungal strains, Penicillium janthinellum, Aspergillus fumigatus, Nigrospora sp. and Stagonosporopsis sp., the effect of the host media and coculturing was investigated and compared to the original axenic culture. Novel compounds as nigrolactone and multiplolide B were reported from the coculture of Nigrospora sp. and Stagonosporopsis sp. with antifungal activity against Aspergillus fumigatus down to MIC 2 μg/mL.; furthermore, the addition of the host extract to the fermentation media helped the production of AM6898A, asperfumol A, asperstone, and 4-epi-brefeldin C with no redundancy in pure PDB media. Even though 4β-acetoxyprobotryane-9β, 15α-diol was previously identified in Botrytis cinerea [112], it was only obtained from the coculture of the two endophytic strains Nigrospora sp. and Stagonosporopsis sp. and absent in the tobacco host media, which manifested the power of coculture to inspire cryptic metabolites [19].

The coculture of the endophyte Penicillium chrysogenum with its host Ziziphus jujuba extract successfully directed the formation of cryptic rare metabolites as spiro-β-lactones and gem-dimethyl hydroxyl products, namely penicichrins A–C with potent activity towards A. fumigatus [107]. Red ginseng coculture with the endophyte A. tubingensis S1120 manifested a better antifungal effect than any of the plant or the monoculture endophytes against A. tubingensis with the production of aspertubin A and panaxytriol whose MIC values were about 8 μg/mL [113]. The butanolide derivative irperide was effective as antifungal against A. fumigatus with MIC value of 1 μg/mL [114].

Eremophilane sesquiterpenes and polyketide terpene hybrids from Paraphaeosphaeria endophytic species cultured with its host Gingko biloba fruit extracts revealed activity towards Alternaria alternata and Beauveria bassiana, yet only alternariol methyl ether showed promising antifungal effect against A. fumigatus, which was correlated to the chromen-6-one nucleus [115].

D. Endophytic metabolites target fungal biofilms in selected pathogens.

Biofilm formation is the culprit behind more than 80% of chronic and 60% of all microbial infections. Fungal biofilm is different from bacterial ones in composition and extracellular matrix, and while bacterial biofilms were subjected to better studies, those of fungi and yeast have only drawn attention recently [116]. In contrast to the free-living cells, fungi forming biofilms are more resistant to treatments and immune system defense mechanisms. C. auris, initially discovered in the external ear canal of a Japanese patient, was recalcitrant to multiple antifungal drugs like polyenes, azoles, and echinocandins; moreover, it is tolerant to high salt and high temperature conditions [117]. Zeng et al. reported rubiginosin C activity against both C. albicans and C. auris where it inhibited yeast to hyphae transformation and biofilm formation with non-significant cytotoxic effect on mammalian cells [118]. Rubiginosin C, isolated from the stromata of Hypoxylon rubiginosum, could be employed as an internal coat to medical devices in a pre-therapeutic application to protect polystyrene material from C. albicans or C. auris adhesion [119] (Fig. 10).

Rubiginosin C, derived from stromata of the ascomycete Hypoxylon rubiginosum, effectively inhibited the formation of biofilms, pseudohyphae, and hyphae in both C. auris and C. albicans without lethal effects. Crystal violet staining assays were utilized to assess the inhibition of biofilm formation, while complementary microscopic techniques, such as confocal laser scanning microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and optical microscopy, were used to investigate the underlying mechanisms. Rubiginosin C is one of the few substances known to effectively target both biofilm formation and the yeast-to-hyphae transition of C. albicans and C. auris within a concentration range not affecting host cells, making it a promising candidate for therapeutic intervention in the future.

The lipophilicity and the long side chain of this azaphilone could contribute to its ease of access in biological membranes. Alternaria tenuissima OE7 endophytes isolated from Ocimum tenuiflorum L. leaves provided a bioactive ethyl acetate extract with a biofilm inhibitory activity against C. albicans at 1.0 mg/mL; moreover, the antifungal potential was evident towards several strains as Candida albicans and C. tropicalis, Microsporum gypseum, A. parasiticus, Trichophyton rubrum, A. flavus, and A. fumigates. The mode of action was examined by scanning electron microscopy and showed to be a fungicidal effect with hyphal and cellular destruction and a synergistic action when taken concomitantly with fluconazole [120].

E. Future perspectives

Multi resistant fungal strains are growing more than any time before, and are considered a major health issue; particularly, to patients with invasive fungal infections affecting blood, brain, gut and lungs. Even worse our arsenal of antifungal drugs is limited, which makes drug discovery of novel antifungal a top health care priority. Recently, the WHO urged researchers to focus on hazardous fungi and yeasts and listed them as A. fumigatus, C. albicans, C. auris and C. neoformans. From the time 1980 to 2024 more than 300 compounds were isolated, identified and tested against these pathogens, yet few of them found their way to clinical trials and subsequently to the market. Our study realigned years of drug discovery against these four fungal and yeast strains and highlighted significant potent molecules to help their drug development process. We emphasize here the significance of endophytic polyketides where more than a third of the reported bioactive molecules belonged to this biogenic origin. Fungal biofilm inhibition is a promising research area in the following years and more studies are warranted in this realm since many molecules can be repurposed here in addition to novel compounds. Development of better culturing procedures can enhance fungal chemo diversity by applying modern OMICS techniques to unveil fungi dark matter. This includes but is not limited to coculturing endophytes either with other microorganisms or their host, which improves cultivability.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Deshmukh SK, Gupta MK, Prakash V, Saxena S. Endophytic fungi: a source of potential antifungal compounds. J Fungi. 2018;4(3):77.

World Health Organisation. Global research agenda for antimicrobial resistance in human health. 2023.

AbdelRazek MMM, Elissawy AM, Mostafa NM, Moussa AY, Elanany MA, Elshanawany MA, Singab ANB. Chemical and biological review of endophytic fungi associated with Morus sp. (Moraceae) and in silico study of their antidiabetic potential. Molecules. 2023;28(4):1718.

Kemkuignou BM, Moussa AY, Decock C, Stadler M. Terpenoids and meroterpenoids from cultures of two grass-associated species of Amylosporus (Basidiomycota). J Nat Prod. 2022;85(4):846–56.

Moussa AY, Sobhy HA, Eldahshan OA, Singab ANB. Caspicaiene: a new kaurene diterpene with anti-tubercular activity from an Aspergillus endophytic isolate in Gleditsia caspia desf. Nat Prod Res. 2021;35(24):5653–64.

Subban K, Subramani R, Johnpaul M. A novel antibacterial and antifungal phenolic compound from the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis mangiferae. Nat Prod Res. 2013;27(16):1445–9.

Erfandoust R, Habibipour R, Soltani J. Antifungal activity of endophytic fungi from Cupressaceae against human pathogenic Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus niger. J Mycol Med. 2020;30(3):100987.

Sen P, Vijay M, Singh S, Hameed S, Vijayaraghavan P. Understanding the environmental drivers of clinical azole resistance in Aspergillus species. Drug Target Insights. 2022;16:25–35.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antimicrobial resistance-Aspergillus: DF-1.7 4 0 obj<</BitsPerComponent 8/ColorSpace/DeviceRGB/Filter /DCTDecode/Height 106/Length 10461/Subtype/Image/Type/XObject/Width 10106>>stream ÿØÿà. 2024.

Zafar H, Altamirano S, Ballou ER, Nielsen K. A titanic drug resistance threat in Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019;52:158–64.

Pereira CB, Pereira de Sá N, Borelli BM, Rosa CA, Barbeira PJS, Cota BB, Johann S. Antifungal activity of eicosanoic acids isolated from the endophytic fungus Mycosphaerella sp. against Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii. Microb Pathog. 2016;100:205–12.

Ademe M, Girma F. Candida auris: from multidrug resistance to pan-resistant strains. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:1287–94.

Li X, Li Y, Wang R, Wang Q, Lu L. Toxoflavin produced by Burkholderia gladioli from Lycoris aurea is a new broad-spectrum fungicide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85(9): e00106.

Chen L, Shi H, Heng J, Wang D, Bian K. Antimicrobial, plant growth-promoting and genomic properties of the peanut endophyte Bacillus velezensis LDO2. Microbiol Res. 2019;218:41–8.

Nisa S, Shoukat M, Bibi Y, Al Ayoubi S, Shah W, Masood S, Sabir M, Asma Bano S, Qayyum A. Therapeutic prospects of endophytic Bacillus species from Berberis lycium against oxidative stress and microbial pathogens. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29(1):287–95.

Dumigan CR, Deyholos MK. Cannabis seedlings inherit seed-borne bioactive and anti-fungal endophytic bacilli. Plants. 2022;11(16):2127.

Boiu-Sicuia OA, Toma RC, Diguță CF, Matei F, Cornea CP. In vitro evaluation of some endophytic Bacillus to potentially inhibit grape and grapevine fungal pathogens. Plants. 2023;12(13):2553.

Xu D, Zhang BY, Yang XL. Antifungal monoterpene derivatives from the plant endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis foedan. Chem Biodivers. 2016;13(10):1422–5.

Chen J-X, Xia D-D, Yang X-Q, Yang Y-B, Ding Z-T. The antifeedant and antifungal cryptic metabolites isolated from tobacco endophytes induced by host medium and coculture. Fitoterapia. 2022;163:105335.

Yang HG, Zhao H, Li JJ, Chen SM, Mou LM, Zou J, Chen GD, Qin SY, Wang CX, Hu D, Yao XS, Gao H. Phyllomeroterpenoids A-C, multi-biosynthetic pathway derived meroterpenoids from the TCM endophytic fungus Phyllosticta sp. and their antimicrobial activities. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12925.

Wu LS, Jia M, Chen L, Zhu B, Dong HX, Si JP, Peng W, Han T. Cytotoxic and antifungal constituents isolated from the metabolites of endophytic fungus DO14 from Dendrobium officinale. Molecules. 2015;21(1):E14.

Peláez F, Cabello A, Platas G, Díez MT, González del Val A, Basilio A, Martán I, Vicente F, Bills GE, Giacobbe RA, Schwartz RE, Onish JC, Meinz MS, Abruzzo GK, Flattery AM, Kong L, Kurtz MB. The discovery of enfumafungin, a novel antifungal compound produced by an endophytic Hormonema species biological activity and taxonomy of the producing organisms. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2000;23(3):333–43.

Gintjee TJ, Donnelley MA, Thompson GR. Aspiring antifungals: review of current antifungal pipeline developments. J Fungi. 2020;6(1):28.

Jallow S, Govender NP. Ibrexafungerp: a first-in-class oral triterpenoid glucan synthase inhibitor. J Fungi. 2021;7(3):163.

Cabello MA, Platas G, Collado J, Díez MT, Martín I, Vicente F, Meinz M, Onishi JC, Douglas C, Thompson J, Kurtz MB, Schwartz RE, Bills GF, Giacobbe RA, Abruzzo GK, Flattery AM, Kong L, Peláez F. Arundifungin, a novel antifungal compound produced by fungi: biological activity and taxonomy of the producing organisms. Int Microbiol. 2001;4(2):93–102.

Casella TM, Eparvier V, Mandavid H, Bendelac A, Odonne G, Dayan L, Duplais C, Espindola LS, Stien D. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic secondary metabolites from tropical leaf endophytes: isolation of antibacterial agent pyrrocidine C from Lewia infectoria SNB-GTC2402. Phytochemistry. 2013;96:370–7.

Jerram WA, Mcinnes AG, Maass WSG, Smith DG, Taylor A, Walter JA. The chemistry of cochliodinol, a metabolite of Chaetomium spp. Can J Chem. 1975;53:2031–2031.

Intaraudom C, Boonyuen N, Suvannakad R, Rachtawee P, Pittayakhajonwut P. Penicolinates A–E from endophytic Penicillium sp. BCC16054. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54(8):744–8.

Liu JY, Song YC, Zhang Z, Wang L, Guo ZJ, Zou WX, Tan RX. Aspergillus fumigatus CY018, an endophytic fungus in Cynodon dactylon as a versatile producer of new and bioactive metabolites. J Biotechnol. 2004;114(3):279–87.

Lv J, Zhou H, Dong L, Wang H, Yang L, Yu H, Wu P, Zhou L, Yang Q, Liang Y, Luo B. Three new furanones from endophytic fungus Hypoxylon vinosopulvinatum DYR-1-7 from Cinnamomum cassia with their antifungal activity. Nat Prod Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2023.2218530.

Peng F, Hou SY, Zhang TY, Wu YY, Zhang MY, Yan XM, Xia MY, Zhang YX. Cytotoxic and antimicrobial indole alkaloids from an endophytic fungus Chaetomium sp. SYP-F7950 of Panax notoginseng. RSC Adv. 2019;9(49):28754–63.

Du L, Haldar S, King JB, Mattes AO, Srivastava S, Wendt KL, You J, Cunningham C, Cichewicz RH. Persephacin is a broad-spectrum antifungal aureobasidin metabolite that overcomes intrinsic resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. J Nat Prod. 2023;86(8):1980–93.

Pereira CB, De Oliveira DM, Hughes AF, Kohlhoff M, La Vieira M, Martins Vaz AB, Ferreira MC, Carvalho CR, Rosa LH, Rosa CA, Alves T, Zani CL, Johann S, Cota BB. Endophytic fungal compounds active against Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii. J Antibiot. 2015;68(7):436–44.

Ezra D, Castillo UF, Strobel GA, Hess WM, Porter H, Jensen JB, Condron MAM, Teplow DB, Sears J, Maranta M, Hunter M, Weber B, Yaver D. Coronamycins, peptide antibiotics produced by a verticillate Streptomyces sp. (MSU-2110) endophytic on Monstera sp. Microbiology. 2004;150(Pt 4):785–93.

Ibrahim SRM, Abdallah HM, Elkhayat ES, Al Musayeib NM, Asfour HZ, Zayed MF, Mohamed GA. Fusaripeptide A: new antifungal and anti-malarial cyclodepsipeptide from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2018;20(1):75–85.

Ibrahim SRM, Elkhayat ES, Mohamed GAA, Fat’hi SM, Ross SA. Fusarithioamide A, a new antimicrobial and cytotoxic benzamide derivative from the endophytic fungus Fusarium chlamydosporium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;479(2):211–6.

Ibrahim SRM, Mohamed GA, Al Haidari RA, Zayed MF, El-Kholy AA, Elkhayat ES, Ross SA. Fusarithioamide B, a new benzamide derivative from the endophytic fungus Fusarium chlamydosporium with potent cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018;26(3):786–90.

Siriwach R, Kinoshita H, Kitani S, Igarashi Y, Pansuksan K, Panbangred W, Nihira T. Bipolamides A and B, triene amides isolated from the endophytic fungus Bipolaris sp. MU34. J Antibiot. 2014;67(2):167–70.

Peng W, Tan J, Sang Z, Huang Y, Xu L, Zheng Y, Qin S, Tan H, Zou Z. Koninginins X–Z, three new polyketides from Trichoderma koningiopsis SC-5. Molecules. 2023;28(23):7848.

Abdelgawad MA, Hamed AA, Nayl AA, Badawy M, Ghoneim MM, Sayed AM, Hassan HM, Gamaleldin NM. The chemical profiling, docking study, and antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of the Endophytic fungi Aspergillus sp. AP5. Molecules. 2022;27(5):1704.

Che Y, Gloer JB, Koster B, Malloch D. Decipinin A and decipienolides A and B: new bioactive metabolites from the coprophilous fungus Podospora decipiens. J Nat Prod. 2002;65(6):916–9.

Jongrungruangchok S, Kittakoop P, Yongsmith B, Bavovada R, Tanasupawat S, Lartpornmatulee N, Thebtaranonth Y. Azaphilone pigments from a yellow mutant of the fungus Monascus kaoliang. Phytochemistry. 2004;65(18):2569–75.

Cui CB, Ubukata M, Kakeya H, Onose R, Okada G, Takahashi I, Isono K, Osada H. Acetophthalidin, a novel inhibitor of mammalian cell cycle, produced by a fungus isolated from a sea sediment. J Antibiot. 1996;49(2):216–9.

Ding G, Liu S, Guo L, Zhou Y, Che Y. Antifungal metabolites from the plant endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis foedan. J Nat Prod. 2008;71(4):615–8.

Schwaben J, Cordes J, Harms K, Koert U. Total synthesis of (+)pestaphthalide A and (-)pestaphthaide B. Synthesis. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1260166.

Chen C, Tao H, Chen W, Yang B, Zhou X, Luo X, Liu Y. Recent advances in the chemistry and biology of azaphilones. RSC Adv. 2020;10(17):10197–220.

Liu L, Liu S, Jiang L, Chen X, Guo L, Che Y. Chloropupukeananin, the first chlorinated pupukeanane derivative, and its precursors from Pestalotiopsis fici. Org Lett. 2008;10(7):1397–400.

Liu X, Dong M, Chen X, Jiang M, Lv X, Zhou J. Antimicrobial activity of an endophytic Xylaria sp.YX-28 and identification of its antimicrobial compound 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;78(2):241–7.

Liu L, Liu S, Chen X, Guo L, Che Y. Pestalofones A–E, bioactive cyclohexanone derivatives from the plant endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis fici. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17(2):606–13.

Jia J, Ford E, Hobbs SM, Baird SM, Lu SE. Occidiofungin is the key metabolite for antifungal activity of the endophytic bacterium Burkholderia sp. MS455 against Aspergillus flavus. Phytopathology. 2022;112(3):481–91.

Ellis D, Gosai J, Emrick C, Heintz R, Romans L, Gordon D, Lu S-E, Austin F, Smith L. Occidiofungin’s chemical stability and in vitro potency against Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(2):765–9.

Wei J, Liu LL, Dong S, Li H, Tang D, Zhang Q, Xue QH, Gao JM. Gabosines P and Q, new carbasugars from Streptomyces sp. and their α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016;26(20):4903–6.

Huang R, Jiang BG, Li XN, Wang YT, Liu SS, Zheng KX, He J, Wu SH. Polyoxygenated cyclohexenoids with promising α-glycosidase inhibitory activity produced by Phomopsis sp. YE3250, an endophytic fungus derived from Paeonia delavayi. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(5):1140–6.

Beattie KD, Ellwood N, Kumar R, Yang X, Healy PC, Choomuenwai V, Quinn RJ, Elliott AG, Huang JX, Chitty JL, Fraser JA, Cooper MA, Davis RA. Antibacterial and antifungal screening of natural products sourced from Australian fungi and characterisation of pestalactams D–F. Phytochemistry. 2016;124:79–85.

von Bargen KW, Niehaus E-M, Krug I, Bergander K, Würthwein E-U, Tudzynski B, Humpf H-U. Isolation and structure elucidation of Fujikurins A–D: products of the PKS19 gene cluster in Fusarium fujikuroi. J Nat Prod. 2015;78(8):1809–15.

Brady SF, Clardy J. CR377, a new pentaketide antifungal agent isolated from an endophytic fungus. J Nat Prod. 2000;63(10):1447–8.

Gao Y, Wang L, Kalscheuer R, Liu Z, Proksch P. Antifungal polyketide derivatives from the endophytic fungus Aplosporella javeedii. Bioorg Med Chem. 2020;28(10):115456.

Wang C, Lu H, Lan J, Zaman K, Cao S. A review: halogenated compounds from marine fungi. Molecules. 2021;26(2):458.

Zhao M, Yuan LY, Guo DL, Ye Y, Da-Wa ZM, Wang XL, Ma FW, Chen L, Gu YC, Ding LS, Zhou Y. Bioactive halogenated dihydroisocoumarins produced by the endophytic fungus Lachnum palmae isolated from Przewalskia tangutica. Phytochemistry. 2018;148:97–103.

Abdou R, Scherlach K, Dahse HM, Sattler I, Hertweck C. Botryorhodines A–D, antifungal and cytotoxic depsidones from Botryosphaeria rhodina, an endophyte of the medicinal plant Bidens pilosa. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(1):110–6.

Sugijanto NE, Diesel A, Rateb M, Pretsch A, Gogalic S, Zaini NC, Ebel R, Indrayanto G. Lecythomycin, a new macrolactone glycoside from the endophytic fungus Lecythophora sp. Nat Prod Commun. 2011;6(5):677–8.

Wang X, Wedge DE, Cutler SJ. Chemical and biological study of cladosporin, an antimicrobial inhibitor: a review. Nat Prod Commun. 2016;11(10):1595–600.

Saetang P, Rukachaisirikul V, Phongpaichit S, Preedanon S, Sakayaroj J, Borwornpinyo S, Seemakhan S, Muanprasat C. Depsidones and an α-pyrone derivative from Simplicillium sp. PSU-H41, an endophytic fungus from Hevea brasiliensis leaf [corrected]. Phytochemistry. 2017;143:115–23.

Rukachaisirikul V, Chinpha S, Saetang P, Phongpaichit S, Jungsuttiwong S, Hadsadee S, Sakayaroj J, Preedanon S, Temkitthawon P, Ingkaninan K. Depsidones and a dihydroxanthenone from the endophytic fungi Simplicillium lanosoniveum (J.F.H. Beyma) Zare & W. Gams PSU-H168 and PSU-H261. Fitoterapia. 2019;138:104286.

Arunpanichlert J, Rukachaisirikul V, Sukpondma Y, Phongpaichit S, Tewtrakul S, Rungjindamai N, Sakayaroj J. Azaphilone and isocoumarin derivatives from the endophytic fungus Penicillium sclerotiorum PSU-A13. Chem Pharm Bull. 2010;58(8):1033–6.

Sun ZL, Zhang M, Zhang JF, Feng J. Antifungal and cytotoxic activities of the secondary metabolites from endophytic fungus Massrison sp. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(10):859–62.

Wei PP, Ai HL, Shi BB, Ye K, Lv X, Pan XY, Ma XJ, Xiao D, Li ZH, Lei XX. Paecilins F–P, new dimeric chromanones isolated from the endophytic fungus Xylaria curta E10, and structural revision of paecilin A. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:922444.

Mohamed H, Ebrahim W, El-Neketi M, Awad MF, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Song Y. In vitro phytobiological investigation of bioactive secondary metabolites from the Malus domestica-derived endophytic fungus Aspergillus tubingensis strain AN103. Molecules. 2022;27(12):3762.

Lohse MB, Gulati M, Johnson AD, Nobile CJ. Development and regulation of single- and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(1):19–31.

Tang J, Huang X, Cao MH, Wang Z, Yu Z, Yan Y, Huang JP, Wang L, Huang SX. Mono-/bis-alkenoic acid derivatives from an endophytic fungus Scopulariopsis candelabrum and their antifungal activity. Front Chem. 2021;9:812564.

Guo L, Wu JZ, Han T, Cao T, Rahman K, Qin LP. Chemical composition, antifungal and antitumor properties of ether extracts of Scapania verrucosa Heeg. and its endophytic fungus Chaetomium fusiforme. Molecules. 2008;13(9):2114–25.

Hagag A, Abdelwahab MF, Abd El-Kader AM, Fouad MA. The endophytic Aspergillus strains: a bountiful source of natural products. J Appl Microbiol. 2022;132(6):4150–69.

Mohamed GA, Ibrahim SR, Asfour HZ. Antimicrobial metabolites from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus versicolor. Phytochem Lett. 2020;35:152–5.

Peng W, You F, Li XL, Jia M, Zheng CJ, Han T, Qin LP. A new diphenyl ether from the endophytic fungus Verticillium sp. isolated from Rehmannia glutinosa. Chin J Nat Med. 2013;11(6):673–5.

Trofast J, Wickberg B. Mycorrhizin A and chloromycorrhizin A, two antibiotics from a mycorrhizal fungus of Monotropa hypopitys L. Tetrahedron. 1977;33(8):875–9.

Koft ER, Smith AB III. Total synthesis of (.+-.)-mycorrhizin A and (.+-.)-dechloromycorrhizin A. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104(9):2659–61.

Demir Ö, Zeng H, Schulz B, Schrey H, Steinert M, Stadler M, Surup F. Bioactive compounds from an endophytic Pezicula sp. showing antagonistic effects against the ash dieback pathogen. Biomolecules. 2023;13(11):1632.

de Oliveira DM, Pereira CB, Mendes G, Junker J, Kolloff M, Rosa LH, Rosa CA, Alves TMA, Zani CL, Johann S, Cota BB. Two new usnic acid derivatives from the endophytic fungus Mycosphaerella sp. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2018;73(11–12):449–55.

Vaz AB, Mota RC, Bomfim MR, Vieira ML, Zani CL, Rosa CA, Rosa LH. Antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi associated with Orchidaceae in Brazil. Can J Microbiol. 2009;55(12):1381–91.

González-Menéndez V, Crespo G, de Pedro N, Diaz C, Martín J, Serrano R, Mackenzie TA, Justicia C, González-Tejero MR, Casares M, Vicente F, Reyes F, Tormo JR, Genilloud O. Fungal endophytes from arid areas of Andalusia: high potential sources for antifungal and antitumoral agents. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9729.

Gurgel RS, de Melo Pereira DÍ, Garcia AVF, Fernandes de Souza AT, Mendes da Silva T, de Andrade CP, Lima da Silva W, Nunez CV, Fantin C, de Lima Procópio RE, Albuquerque PM. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of endophytic fungi associated with Arrabidaea chica (Bignoniaceae). J Fungi. 2023;9(8):864.

Katoch M, Pull S. Endophytic fungi associated with Monarda citriodora, an aromatic and medicinal plant and their biocontrol potential. Pharm Biol. 2017;55(1):1528–35.

Xing YM, Chen J, Cui JL, Chen XM, Guo SX. Antimicrobial activity and biodiversity of endophytic fungi in Dendrobium devonianum and Dendrobium thyrsiflorum from Vietnam. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62(4):1218–24.

Yu H, Zhang L, Li L, Li W, Han T, Guo L, Qin L. Endophytic fungi from Ginkgo biloba and their biological activities. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2010;35(16):2133–7.

He J, Chen J, Zhao QM, Qi HB. Study on fast screening antifungus activity of endophytes from Pseudolarix kaempferi. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2006;31(21):1759–63.

Vicente MF, Basilio A, Cabello A, Peláez F. Microbial natural products as a source of antifungals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(1):15–32.

Zida A, Bamba S, Yacouba A, Ouedraogo-Traore R, Guiguemdé RT. Anti-Candida albicans natural products, sources of new antifungal drugs: a review. J Mycol Med. 2017;27(1):1–19.

Haque E, Irfan S, Kamil M, Sheikh S, Hasan A, Ahmad A, Lakshmi V, Nazir A, Mir SS. Terpenoids with antifungal activity trigger mitochondrial dysfunction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 2016;85(4):436–43.

Li Y, Shao X, Xu J, Wei Y, Xu F, Wang H. Tea tree oil exhibits antifungal activity against Botrytis cinerea by affecting mitochondria. Food Chem. 2017;234:62–7.

Cieslik W, Szczepaniak J, Krasowska A, Musiol R. Antifungal styryloquinolines as Candida albicans efflux pump inhibitors: styryloquinolines are ABC transporter inhibitors. Molecules. 2020;25(2):345.

Kreuzenbeck NB, Dhiman S, Roman D, Burkhardt I, Conlon BH, Fricke J, Guo H, Blume J, Görls H, Poulsen M, Dickschat JS, Köllner TG, Arndt H-D, Beemelmanns C. Isolation, (bio)synthetic studies and evaluation of antimicrobial properties of drimenol-type sesquiterpenes of Termitomyces fungi. Commun Chem. 2023;6(1):79.

Edouarzin E, Horn C, Paudyal A, Zhang C, Lu J, Tong Z, Giaever G, Nislow C, Veerapandian R, Hua DH, Vediyappan G. Broad-spectrum antifungal activities and mechanism of drimane sesquiterpenoids. Microb Cell. 2020;7(6):146–59.

Yang A, Hong Y, Zhou F, Zhang L, Zhu Y, Wang C, Hu Y, Yu L, Chen L, Wang X. Endophytic microbes from medicinal plants in fenghuang mountain as a source of antibiotics. Molecules. 2023;28(17):6301.

Wardecki T, Brötz E, De Ford C, von Loewenich FD, Rebets Y, Tokovenko B, Luzhetskyy A, Merfort I. Endophytic Streptomyces in the traditional medicinal plant Arnica montana L.: secondary metabolites and biological activity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2015;108(2):391–402.

Jog R, Pandya M, Nareshkumar G, Rajkumar S. Mechanism of phosphate solubilization and antifungal activity of Streptomyces spp. isolated from wheat roots and rhizosphere and their application in improving plant growth. Microbiology. 2014;160(Pt 4):778–88.

Chandrakar S, Gupta AK. Studies on the production of broad spectrum antimicrobial compound polypeptide (actinomycins) and lipopeptide (fengycin) from Streptomyces sp. K-R1 associated with root of abutilon indicum against multidrug resistant human pathogens. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2019;25(2):779–98.

Xia X, Li Q, Li J, Shao C, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Liu X, Lin Y, Liu C, She Z. Two new derivatives of griseofulvin from the mangrove endophytic fungus Nigrospora sp. (strain No. 1403) from Kandelia candel (L.) Druce. Planta Med. 2011;77(15):1735–8.

Flewelling AJ, Ellsworth KT, Sanford J, Forward E, Johnson JA, Gray CA. Macroalgal endophytes from the Atlantic Coast of Canada: a potential source of antibiotic natural products? Microorganisms. 2013;1(1):175–87.

Yin Y, Tan Q, Wu J, Chen T, Yang W, She Z, Wang B. The polyketides with antimicrobial activities from a mangrove endophytic fungus Trichoderma lentiforme ML-P8-2. Mar Drugs. 2023;21(11):566.

Klaiklay S, Rukachaisirikul V, Phongpaichit S, Buatong J, Preedanon S, Sakayaroj J. Flavodonfuran: a new difuranylmethane derivative from the mangrove endophytic fungus Flavodon flavus PSU-MA201. Nat Prod Res. 2013;27(19):1722–6.

Li SJ, Jiao FW, Li W, Zhang X, Yan W, Jiao RH. Cytotoxic xanthone derivatives from the mangrove-derived endophytic fungus Peniophora incarnata Z4. J Nat Prod. 2020;83(10):2976–82.

Wang P, Luo Y-F, Zhang M, Dai J-G, Wang W-J, Wu J. Three xanthone dimers from the Thai mangrove endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. xy21. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2018;20(3):217–26.

Tan S, Yang B, Liu J, Xun T, Liu Y, Zhou X. Penicillixanthone A, a marine-derived dual-coreceptor antagonist as anti-HIV-1 agent. Nat Prod Res. 2019;33(10):1467–71.

Ding B, Yuan J, Huang X, Wen W, Zhu X, Liu Y, Li H, Lu Y, He L, Tan H, She Z. New dimeric members of the phomoxanthone family: phomolactonexanthones A, B and deacetylphomoxanthone C isolated from the fungus Phomopsis sp. Mar Drugs. 2013;11(12):4961–72.

Zang Z, Yang W, Cui H, Cai R, Li C, Zou G, Wang B, She Z. Two antimicrobial heterodimeric tetrahydroxanthones with a 7,7′-linkage from mangrove endophytic fungus Aspergillus flavus QQYZ. Molecules. 2022;27(9):2691.

Mandala SM, Thornton RA, Rosenbach M, Milligan J, Garcia-Calvo M, Bull HG, Kurtz MB. Khafrefungin, a novel inhibitor of sphingolipid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(51):32709–14.

Li SY, Yang XQ, Chen JX, Wu YM, Yang YB, Ding ZT. The induced cryptic metabolites and antifungal activities from culture of Penicillium chrysogenum by supplementing with host Ziziphus jujuba extract. Phytochemistry. 2022;203:113391.

Alanzi A, Elhawary EA, Ashour ML, Moussa AY. Aspergillus co-cultures: a recent insight into their secondary metabolites and microbial interactions. Arch Pharmacal Res. 2023;46(4):273–98.

Peng XY, Wu JT, Shao CL, Li ZY, Chen M, Wang CY. Co-culture: stimulate the metabolic potential and explore the molecular diversity of natural products from microorganisms. Mar Life Sci Technol. 2021;3(3):363–74.

Triastuti A, Vansteelandt M, Barakat F, Amasifuen C, Jargeat P, Haddad M. Untargeted metabolomics to evaluate antifungal mechanism: a study of Cophinforma mamane and Candida albicans interaction. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2023;13(1):1.

Wicklow DT, Roth S, Deyrup ST, Gloer JB. A protective endophyte of maize: Acremonium zeae antibiotics inhibitory to Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium verticillioides. Mycol Res. 2005;109(Pt 5):610–8.

Durán-Patrón R, Colmenares AJ, Hernández-Galán R, Collado IG. Some key metabolic intermediates in the biosynthesis of botrydial and related compounds. Tetrahedron. 2001;57(10):1929–33.

Wu YM, Yang XQ, Zhao TD, Shi WZ, Sun LJ, Cen RH, Yang YB, Ding ZT. Antifeedant and antifungal activities of metabolites isolated from the coculture of endophytic fungus Aspergillus tubingensis S1120 with red ginseng. Chem Biodivers. 2022;19(1): e202100608.

Wu YM, Yang XQ, Chen JX, Wang T, Li TR, Liao FR, Liu RT, Yang YB, Ding ZT. A new butenolide with antifungal activity from solid co-cultivation of Irpex lacteus and Nigrospora oryzae. Nat Prod Res. 2023;37(13):2243–7.

Su S, Yang XQ, Yang YB, Ding ZT. Antifungal and antifeedant terpenoids from Paraphaeosphaeria sp. cultured by extract of host Ginkgo biloba. Phytochemistry. 2023;210:113651.

Jamal M, Ahmad W, Andleeb S, Jalil F, Imran M, Nawaz MA, Hussain T, Ali M, Rafiq M, Kamil MA. Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. J Chin Med Assoc. 2018;81(1):7–11.

Hernando-Ortiz A, Mateo E, Perez-Rodriguez A, de Groot PWJ, Quindós G, Eraso E. Virulence of Candida auris from different clinical origins in Caenorhabditis elegans and Galleria mellonella host models. Virulence. 2021;12(1):1063–75.

Becker K, Kuhnert E, Cox RJ, Surup F. Azaphilone pigments from Hypoxylon rubiginosum and H. texense: absolute configuration, bioactivity, and biosynthesis. Eur J Org Chem. 2021;2021(36):5094–103.

Zeng H, Stadler M, Abraham W-R, Müsken M, Schrey H. Inhibitory effects of the fungal pigment rubiginosin C on hyphal and biofilm formation in Candida albicans and Candida auris. J Fungi. 2023;9(7):726.

Chatterjee S, Ghosh R, Mandal NC. Inhibition of biofilm- and hyphal- development, two virulent features of Candida albicans by secondary metabolites of an endophytic fungus Alternaria tenuissima having broad spectrum antifungal potential. Microbiol Res. 2020;232:126386.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AYM: conceptualization, visualization, writing draft, revising, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Moussa, A.Y. The limitless endophytes: their role as antifungal agents against top priority pathogens. Microb Cell Fact 23, 161 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-024-02411-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-024-02411-3