Abstract

Background

γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a bioactive compound produced by lactic acid bacteria (LAB). The diversity of GABA production in the Lactococcus genus is poorly understood. Genotypic and phenotypic approaches were therefore combined in this study to shed light on this diversity. A comparative genomic study was performed on the GAD-system genes (gadR, gadC and gadB) involved in GABA production in 36 lactococci including L. lactis and L. cremoris species. In addition, 132 Lactococcus strains were screened for GABA production in culture medium supplemented with 34 mM L-glutamic acid with or without NaCl (0.3 M).

Results

Comparative analysis of the nucleotide sequence alignments revealed the same genetic organization of the GAD system in all strains except one, which has an insertion sequence element (IS981) into the PgadCB promoter. This analysis also highlighted several deletions including a 3-bp deletion specific to the cremoris species located in the PgadR promoter, and a second 39-bp deletion specific to L. cremoris strains with a cremoris phenotype. Phenotypic analysis revealed that GABA production varied widely, but it was higher in L. lactis species than in L. cremoris, with an exceptional GABA production of up to 14 and 24 mM in two L. lactis strains. Moreover, adding chloride increased GABA production in some L. cremoris and L. lactis strains by a factor of up to 16 and GAD activity correlated well with GABA production.

Conclusions

This genomic analysis unambiguously characterized the cremoris phenotype of L. cremoris species and modified GadB and GadR proteins explain why the corresponding strains do not produce GABA. Finally, we found that glutamate decarboxylase activity revealing GadB protein amount, varied widely between the strains and correlated well with GABA production both with and without chloride. As this protein level is associated to gene expression, the regulation of GAD gene expression was identified as a major contributor to this diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are widely used in the food industry (cheese, buttermilk, sour cream, yogurt) as acidifiers (converting sugars into lactic acid) [1], food thickeners [2] and as bacteriocin producers [3, 4]. They also contribute to the flavor of dairy products [5] and interest in their potential use as cell factories for the chemical industry (biofuels, solvents, bio-based plastics) has grown in recent years [6,7,8,9]. Another attractive feature of LAB is their ability to produce a range of molecules with healthcare applications such as bioactive peptides, vitamins, hyaluronic acid and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [10,11,12]. GABA, the most widely distributed neurotransmitter in the sympathetic nervous system [13], has been a particular focus of research for several years because of its many health benefits. GABA plays a crucial role in lowering blood pressure, reduces the risk of lung adenocarcinoma, and has been shown to have anti-diabetic, neuroprotective, antidepressant, anti-inflammatory and visceral antinociceptive properties [14,15,16].

The most studied LAB genus to date is Lactobacillus, which is generally considered one of the best for GABA production [17,18,19]. However, Lactococcus species also produce GABA and interest in this genus has gradually increased in recent years. The genome of Lactococcus lactis NCDO2118, a non-dairy GABA-producing bacterium, was sequenced in 2014 [20], and in more recent studies, new lactococci with a high potential for GABA production have been isolated in fermented milk [21, 22] and in fermented fish products [23].

Lactococcus species are found in many ecological niches (milk, plants, digestive tract, etc.) but the two main species of interest in the dairy and nutraceutical industries (following a recent taxonomic reclassification of Lactococcus lactis into two distinct species) are L. lactis and L. cremoris. While these species were previously distinguished based on a handful of phenotypic characteristics, new molecular methods [24,25,26,27] have allowed a better discrimination of these two species, based on average nucleotide identity (ANI) and tetranucleotide frequency correlation coefficients (TETRA) [28]. The cremoris species is phenotypically heterogeneous with strains having the typical cremoris phenotype and others having a lactis phenotype [29, 30]. The cremoris phenotype is characterized by an inability to produce GABA [31], to hydrolyze arginine [32], to grow at 40 °C and in 4% (w/v) NaCl.

GABA is synthesized from glutamate by the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase (GAD). This enzyme participates in the control of the acidification of the cytosolic environment by decarboxylating glutamate (acid substrate) into a neutral compound (GABA) by consuming H + ions, thus effectively protecting cells from acid stress [33, 34]. The glutamate decarboxylase gene is part of a GAD system involving a chloride-dependent gadCB operon (with gadC gene encoding glutamate/GABA antiporter and gadB gene encoding GAD) and gadR gene encoding positive regulator. This genetic organization was proposed in 1998 for a few strains [35, 36] and no further studies of the genetic organization of the GAD system in lactococci have since been published. It is unclear whether this genetic organization is common to all lactococci or just a few. Furthermore, the diversity of GABA production in lactococci has yet to have been studied in detail. Some cremoris strains have been described not to produce GABA [37] but is this a common feature of all L. cremoris strains with the cremoris phenotype? Two further interesting questions are whether and to what extent any L. cremoris species with the lactis phenotype and all L. lactis species produce GABA?

To shed some light on the genetic and phenotypic diversity of lactococci for GABA production, a set of 132 Lactococcus strains from different biotopes was screened for GABA production in semi-synthetic culture medium supplemented with 34 mM L-glutamic acid. The strains were also screened in the presence of chloride. The organisation of the genes involved in GABA production were also analysed and the nucleotide sequences of the genes were compared for 36 lactococci from the initial screening panel to determine whether this diversity in GABA production can be explained by the phenotypic and genotypic data obtained.

Methods

Organisms and growth conditions

The microorganisms used throughout this work were 88 L. lactis strains and 20 L. cremoris strains with the lactis phenotype and 24 L. cremoris strains with the cremoris phenotype from public and private collections. All bacterial strains are listed in Additional file 1 Table S1. The strains were stored at -80 °C in medium supplemented with glycerol (20%) in 96–deep-well plates (30 µL/well).

Screening for GABA production

Overnight cultures (from deep well plates) in semi-synthetic medium (1 mL) containing glucose (20 g/L), yeast extract (YE) (10 g/L) KH2PO4 (9 g/L), K2HPO4 (7.5 g/L), MgSO4 7 H2O (0.2 g/L), MnSO4 (0.05 g/L), grown at 30 °C without shaking, were inoculated (1:6) in 200 µL of fresh medium for 3 h (i.e. until the optical density at 580 nm, OD580, reached 0.6–0.8, corresponding to late-exponential phase cells). For GABA production screening, precultured cells were inoculated at 2.5% in new microplates containing 200 µL of the semi-synthetic medium supplemented with 34 mM L-glutamic acid (the precursor of GABA), with or without NaCl (0.3 M). The initial pH was 6.6. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Biomass production was estimated by measuring OD580 directly in the microplates without sampling every 30 min for 24 h with a microplate reader (SpectraMax Plus, Molecular Devices). Samples (170 µL) were collected at 24 h in order to measure the GABA concentration and arginine consumption (methods described below).

Growth rate measurements at 40 °C and with addition of 4% (w/v) NaCl at 30 °C

Cells were grown overnight as described above for GABA production measurements in the same culture medium. These precultures were then used to inoculate (at 2.5%) two sets of microplates: one containing 200 µL of the semi-synthetic medium incubated at 40 °C, the second containing 200 µL of the semi-synthetic medium with 4% (w/v) NaCl incubated at 30 °C. The initial pH was 6.6. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Flask cultures

To study GAD activity in the presence and absence of chloride, bacterial cells (NCDO2118, S642, EIP3I, NCDO2727, MG1363 strains) were grown under static conditions in flasks containing 500 mL semi-synthetic medium (described above) at 30 °C with and without chloride. Cells from overnight cultures were inoculated to obtain an initial OD580 of 0.25. Flask fermentation experiments were performed in duplicate.

Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring OD580 (Biochrom Libra S11, 1 one unit of absorbance equivalent to 0.3 g/L) on samples collected every 30 min. GAD activity was measured after 6 h in sample volumes containing 150 mg of cells. GABA concentrations were also measured at 6 and 24 h by HPLC.

Growth rate estimates

Maximum growth rates (µmax) were calculated from four to five consecutive OD580 measurements at between 0.5 and 3.0 h of growth in microplates or flasks using the following formula: (µmax = ∆lnOD580/∆t, where t is time).

GABA concentration

GABA and arginine concentrations in culture supernatants were measured by HPLC (Agilent Technologies 1200 Series, Waldbronn, Germany) as previously described [38]. Briefly, proteins in the sample were precipitated by adding four volumes of methanol to one volume of sample and then incubated overnight on ice. The mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant kept for amino acid analysis. The amino acids were automatically derivatized with OrthoPhtalic Aldehyde (OPA) and 9-fluorenylmethyl-chloroformiate (FMOC-C1). The derivatives were separated on a Hypersil AA-ODS column (Agilent Technologies) at 40 °C with a linear gradient of acetate buffer (pH 7.2) with triethylamine (0.018%), tetrahydrofuran (0.3%) and acetonitrile. A diode array detector was used to detect OPA derivatives at 338 nm and FMOC derivatives at 262 nm.

GAD activity measurements

For specific GAD activity measurements, 150 mg of cells were washed twice with 0.2% KCl (w/v) and suspended in 3 mL sodium acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 4.6) containing 4.5 mM MgCl2, 22% (v/v) glycerol, and 1.5 mM DTT. This mixture was divided into three tubes each containing 6 mg of glass beads. The cells were then lysed in a FastPrep-24 homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, Illkirch, France) using 6 cycles of 30 s at 6.5 m/s interrupted by 1 min incubation on ice. Cell debris were removed by centrifugation for 15 min at 10,000× g at 4 °C. The supernatant was used for enzyme assays, and the protein concentration in the extract was measured using the Bradford method. Enzyme assays were performed with 0.5 mL of substrate solution, consisting of 20 mM sodium glutamate and 2 mM pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) incubated at 30 °C then mixed with 0.5 mL supernatant. Samples (100 µL) were taken every 30 min until 4 h and inactivated by boiling for 5 min to stop the decarboxylation reaction. Reaction mixtures were subsequently analyzed for the presence of GABA using HPLC. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that converted 1 mmol of glutamate per min and per g of protein.

RNA extraction and gene expression analysis

A culture volume corresponding to 6 mg dry weight biomass was harvested and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Before cell lysis, each sample was centrifuged (4 °C, 5 min, 4800 rpm), washed with 1 mL of TE buffer (Tris-HCl 10 mM, pH 8, EDTA 1 mM) and resuspended in 500 µL of TE buffer. Cells were disrupted at 4 °C (6.5 m/s, 4 cycles, 30 s, 1 min cooling on ice) on a FastPrep-24 (MP Biomedicals) with glass beads (0.6 g), 25 µL of SDS (20%), and 500 µL of phenol (pH 4.7). Cell debris and phenol were eliminated by centrifugation and (4 °C, 25 min, 13,000 rpm). RNA from the aqueous phase was extracted with RNeasy midi kit (Qiagen). The standard protocol (precipitation, washing and elution) including the DNase I treatment described in the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and quality were measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA). The samples were subjected to reverse transcription using Super Script II reverse transcriptase (LifeTechnology), as previous described [39]. RT-qPCR was performed using a SYBR green-based detection protocol (Life Technology) with an Opticon 2 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) and MyIQ software (Bio-Rad). Primers (Table 1) specificity and PCR efficiency were analyzed on genomic DNA range prior to quantification. The tuf gene was used as internal standards for normalization. Variations of gene expression between strains were calculated with NCDO2727 (condition without chloride) as reference with the ΔΔCt method [40] and expressed as fold changes (FC).

Sequence analysis

All the genome sequences of the representative strains used in this study (except those of strains MG1388, S170, CIRM-BIA 1564 and EIP3I) were obtained from the NCBI database. For strains MG1388, S170, CIRM-BIA 1564 and EIP3I, genomic DNA was extracted using the GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to manufacturer instructions. Short-read whole genome sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, Inc.,San Diego, US-CA) using 2 × 150 bp paired end reads with 100x average coverage. The raw data were analyzed using tools from the GALAXY website (https://usegalaxy.eu/). Briefly, the reads were assembled to contigs using Unicycler (version 0.4.8.0) with bold assembly and default parameters. Contigs shorter than 100 bp were excluded.

The GAD cluster, a region of approximately 4200 bp encompassing the gadR, gadC, gadB genes and their specific promoters, was extracted from the sequences of the representative strains (21 L. lactis strains, 8 L. cremoris strains with the lactis phenotype and 7 L. cremoris strains with the cremoris phenotype) using BLAST software (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The nucleotide sequences were then aligned using the ClustalW algorithm with the software MEGA X (https://www.megasoftware.net/home). All raw and processed sequencing data generated in this study have been submitted to the NCBI BioProject database under accession number PRJNA960850.

Results

Similar organization of GAD system in different lactococci

We investigated the genetic organization of the GAD system by nucleotide sequence alignment in 36 lactococci, including 21 L. lactis and 15 L. cremoris species with an equal number of lactis and cremoris phenotypes for the latter (Additional file 1 Table S1). In all but one of the studied strains, the GAD system was found to be organized in the same way as described by Sanders et al. [37] for L. lactis MG1363, namely with a positive regulator encoded by gadR and expressed from the PgadR promoter and the gadCB operon, consisting of gadC (encoding glutamate/GABA antiporter) and gadB (encoding GAD), located downstream of the PgadCB promoter, ensuring rapid co-regulation of GAD and the transporter (Fig. 1).

Schematic representation of genetic organization of the GAD genes (i.e. regulator gadR, glutamate/GABA antiporter gadC, glutamate decarboxylase gadB, and two promoters PgadR and PgadCB) in lactococci: ∆ (blue) deletions observed in all L. cremoris species relative to L. lactis, ∆ (red) deletion or ▼ (red) insertion only observed in L. cremoris species with the cremoris phenotype, ▼ (grey) insertion site for the IS981 element in L. lactis S642. (not drawn to scale)

The one exception was L. lactis S642, which has a 1226 bp insertion sequence element (IS981) in the PgadCB promoter between the − 10 and − 35 boxes (Fig. 1). This insertion sequence introduces a new − 35 box, leading to a “hybrid” PgadCB promoter with the − 10 box of native PgadCB.

Differences in GAD genes between L. lactis and L. cremoris species

The phylogenetic tree built from the alignment of nucleotide sequences of GAD system genes distinctly highlights the two species, L. lactis and L. cremoris, and also separates the lactis and cremoris phenotypes of L. cremoris strains (Fig. 2). It is remarkable that this phylogenetic tree based only on a comparison of GAD system nucleotide sequences captures the genotype/phenotype disparities within the Lactococcus genus. These results are consistent with those obtained by comparing the entire genomes of L. lactis and L. cremoris species [29].

Phylogenetic tree based on GAD system gene sequences. The tree was generated with the software MEGAX using the maximum likelihood method and the Tamura 3-parameter model with 1,000 bootstraps. The numbers at the branches indicate supporting bootstrap values. The scale bar indicates 0.01 substitution per nucleotide position

Several deletion regions (shown in Fig. 1) were found in the sequences of the GAD genes. A 25-bp and a 13-bp deletion were observed in all L. cremoris species in the 3’ untranslated region of the gadCB operon. These deletions, described previously by Nomura et al. [41], were used to distinguish the two phylogenic groups corresponding to the lactis and cremoris species. Our in-depth analysis of the nucleotide sequences revealed two additional deletions; first, a 3-bp deletion in the PgadR promoter specific to cremoris species; and second, a 39-bp deletion specific to L. cremoris with the cremoris phenotype. This deletion extends 13 bp upstream of the gadR stop codon to the inverted repeats characteristic of the end of the gadR transcript. Since this large deletion has never previously been detected, we confirmed its presence by PCR analysis of seventeen L. cremoris strains with the cremoris phenotype whose sequence is unknown (Additional file 2 Fig. S1). Finally, a single thymine insertion was observed only in L. cremoris with the cremoris phenotype. This insertion, reported previously by Nomura et al. [37], is located in the gadB gene and leads to the formation of a stop codon, producing a truncated GadB protein 56 amino acids shorter than in the other strains.

High and variable levels of GABA production in L. lactis

The diversity of GABA production was studied in 132 Lactococcus strains (the 36 sequenced strains described above and 96 news strains) covering all the different groups (88 L. lactis strains, 20 L. cremoris strains with the lactis phenotype and 24 L. cremoris strains with the cremoris phenotype). Bacterial cells were grown in duplicate in glucose-YE medium supplemented with L-glutamic acid (the precursor for GABA production). Overall, a great diversity of production was achieved with a highly strain-dependent GABA production ranging from 0 to 24 mM between the different lactococci under study (Fig. 3A). This diversity in GABA production was apparently unrelated to the niche of origin of the strains (Additional file 1 Table S1).

GABA production (mM) of 132 lactococci (▲ L. lactis, ♦ L. cremoris phenotype lactis, ● L. cremoris phenotype cremoris) after 24 h of growth on glucose-YE medium supplemented with 34 mM L-glutamic acid without NaCl (A) and with 0.3 M NaCl (B). Values represent the mean of duplicate experiments. The strains mentioned in the text are MG1363, a L. cremoris strain with a lactis phenotype ♦, and NCDO2118, NCDO2727, S642 and EIP3I, which are L. lactis strains▲

The strains that did not produce GABA are all of L. cremoris species with the cremoris phenotype. These strains all have the following phenotypic characteristics: no growth at 40 °C or in 4% (w/v) NaCl and inability to deaminate arginine (Additional file 1 Table S1). These phenotypic characteristics were never found together in any of the L. lactis strains or in any of the L. cremoris strains with a lactis phenotype, which produced very little GABA (Additional file 1 Table S1).

GABA production in the L. cremoris strains with a lactis phenotype ranged from 0.3 to 0.8 mM (0.55 ± 0.16 mM on average), demonstrating that GABA production varies little in this group. The MG1363 strain (highlighted in Fig. 3A), which is often used as a model strain in the literature, does not appear to be a good GABA producer as it only yielded 0.62 mM GABA. Although a majority (61%) of L. lactis strains produced GABA at similar concentrations (0.59 ± 0.21 mM) as those produced by L. cremoris with the phenotype lactis, several L. lactis strains were found to produce between 1 and 2.5 mM GABA and four L. lactis strains produced GABA at more than 2.5 mM, notably L. lactis NCDO2118, (highlighted in Fig. 3A) which produced 3.85 mM GABA. These production levels were greatly exceeded by two other L. lactis strains: L. lactis S642 and L. lactis EIP3I, which respectively yielded 14 and 24 mM GABA (Fig. 3A). These values were unexpected based on the literature and illustrate the great variability of GABA production in lactococci and particularly among L. lactis strains.

Strain-dependent and variable effect of chloride on GABA production

Chloride ions are considered to be the most important factor for GABA production in lactococci [42]. We therefore investigated the existence and magnitude of any chloride-mediated increase in GABA production among the 132 studied strains, by growing them in the same conditions in the presence of 0.3 M NaCl.

The increase in GABA production in the presence of chloride varied considerably between strains (Fig. 3B). For some strains, no increase in GABA production was observed. In particular, L. cremoris strains with the phenotype cremoris remained unable to produce GABA (Fig. 3B). Similarly, the low levels of GABA production observed for some L. lactis strains remained unchanged in the presence of chloride; for instance, the NCDO2727 strain highlighted in Fig. 3 produced the same low level of GABA (about 0.2 mM) with and without NaCl. For a small number of lactococci, an unexpected decrease in GABA production was even observed. L. lactis S642 for example, which stood out by its high production capacity of 14.4 mM in the absence of chloride, produced just 9.3 mM GABA in the presence of chloride (Fig. 3B). However, for the large majority of lactococci, GABA production was higher in the presence of chloride, but with highly variable increases ranging from 1.2 to 16-fold depending on the strain. For example, in the presence of chloride, L. lactis NCDO2118 and L. cremoris MG1363 with a lactis phenotype (Fig. 3B) respectively produced 4 and 12 times more GABA than without chloride (15 and 7 mM versus 3.8 and 0.6 mM, respectively). Although the overall increase in GABA production was greater for L. lactis strains (1.1 to 28 mM) than for L. cremoris with the lactis phenotype (1.1 to 11 mM), the variability of the effect of chloride was similar for both groups, with increases ranging in both cases from 1.2- to 16-fold (Additional file 1 Table S1).

As adding chloride impacts growth rates, we evaluated whether this could have also affected GABA production. Growth rates varied from 0.24 to 1.14 h-1 without chloride and from 0.10 to 0.75 h-1 with chloride. However, levels of GABA production were not correlated to growth rate as shown by the scatter plots in the presence and absence of chloride (Additional file 3 Fig. S2). Thus, growth rate variability was not a major contributing factor to the diversity in GABA production of the studied lactococci.

High variability in GAD activity and expression level of GAD genes

To go further in the understanding of this GABA production variability, we studied the potential relationship between GABA production and the specific activity of the GAD enzyme or the expression level of GAD genes. GAD activity measured in vitro under optimum culture conditions (i.e., maximum activity) reveals the expression level of the protein encoded by the gadB gene. This study was carried out on a limited panel of five strains selected to reflect the profiles highlighted above, namely four L. lactis strains (S642, EIP3I, NCDO2118, NCDO2727) and one L. cremoris strain with the lactis phenotype (MG1363), with markedly different levels of GABA production with and without NaCl (as shown in Fig. 3A/B). GAD specific activity varied considerably between strains and between culture conditions (Table 2). In the absence of chloride, GAD activities varied from 0.8 to 132 mmol/min/g protein and reached as high as 1464 mmol/min/g protein in the presence of chloride. Thus, the effect of chloride is also variable. GAD activity increased by a factor of 11, 43 and 45 in the EIP3I, NCDO2118, and MG1363 strains, respectively (Table 2), but remained constant in the NCDO2727 strain.

At the same time, GABA production varied widely, from 0.3 to a maximum of 17.5 mM. Under all these conditions and media and in all these strains, GAD activity was well correlated with GABA production (Fig. 4A), indicating that cellular GAD activity is a key determinant of GABA production. To go further understand the regulation of GABA production regulation, we measured the expression of the genes in the GAD system (Additional file 4). GAD activity correlated well with the expression of the gad CB operon (gadB gene encoding glutamate decarboxylase and gadC gene encoding glutamate/GABA antiporter) (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, no link was observed between the expression of gadR, the regulator of the GAD system, and GAD activity.

GABA production (mM) after 24 h of growth on glucose-YE medium supplemented with 34 mM L-glutamic acid for five strains without NaCl (filled symbol) and with 0.3 M NaCl (empty symbol) compared to specific GAD activity (mmol/min/g protein) (A) and specific GAD activity compared to gene expression fold change (FC) of gadC ∆▲ and gadB ○● (B)

Discussion

The multiple health benefits of GABA have led to growing research interest. While GABA can be produced by chemical synthesis or by enzymatic biocatalysis [43, 44], studies have mainly focused on microbial fermentation [45,46,47]. Many strains of LAB can produce GABA, with Lactobacillus strains among the most efficient GABA producers described to date [48, 49]. Here, we studied the diversity of GABA production in lactococci to demonstrate that the Lactococcus genus is also an excellent candidate to synthesis great amounts of GABA.

The screening data obtained in this work highlights the wide range of GABA production levels in the panel of selected strains. However, the genetic organization of the GAD system was very similar in all studied lactococci bar one, L. lactis S642, where the presence of an IS981 insertion sequence in the PgadCB promoter moves the − 35 box away from the − 10 box. This IS981 element creates a new − 35 box, leading to a “hybrid” PgadCB promoter with the − 10 box of native PgadCB,, which probably affects the transcription of the gadCB operon and hence GABA production by this strain. The effect of an IS981 insertion on transcription has been described previously for other genes [50,51,52,53].

In spite of the similar genetic organization, GABA production varied greatly between the studied strains and was always zero for L. cremoris strains with the cremoris phenotype. Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed a specific 39-bp deletion for this lineage encompassing the 3’ end of the gadR gene and the transcription terminator. This probably affects gadR’s mRNA and as a result, the positive regulator GadR. Gong et al. [54] completely inactivated gadR in Lactobacillus brevis ATCC 367, leading to non-production of GABA through decreased expression of gadC and gadB. Furthermore, the insertion of a thymine into the gadB gene introduces a stop codon, shortening the GadB protein by 56 amino acids, and probably rendering it non-functional. Thus, the inability of L. cremoris strains with the cremoris phenotype to produce GABA, under all tested growing conditions, can be explained by altered GAD system sequences. These strains were also unable to produce ornithine from arginine. The two major pathways involved in resistance to acidic conditions are thus lacking in L. cremoris strains with the cremoris phenotype and this may explain the widely recognised strong acidifying properties of these strains.

A broad distribution of GABA production levels was also observed in the L. cremoris strains with a lactis phenotype, but GABA production varied more strongly and more widely in L. lactis than in L. cremoris species. Several genotypic observations may partly explain this difference. Firstly, a specific 3-bp deletion was observed in the PgadR promoter in cremoris species. This deletion in the 5’UTR could reduce the efficiency of the PgadR promoter relative to L. lactis strains and may thus lead to decreased gadR transcription and gadCB expression. This could contribute to the lower GABA production observed for L. cremoris with the lactis phenotype compared to L. lactis. Secondly, we identified a large number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the GAD system genes in L. lactis strains. These SNPs do not involve active site residues and no correlation was found between these SNPs and GABA production. Thus, the genomic polymorphisms do not of themselves explain the diversity of GABA production observed in the L. lactis strains. On the other hand, the strong correlation between GABA production and cellular GAD activity, directly related to gadB gene expression, indicates that regulation of GAD gene expression is a major contributor to this diversity.

Finally, chloride ions were observed to have a strong effect on GABA production in lactococci. This effect has never previously been observed in LAB, whose Lactobacillus strains [49, 55]. Our results demonstrate the effect of chloride on the diversity of GABA production in lactococci. A majority of L. lactis and L. cremoris with the lactis phenotype produced more GABA (1.2 to 16 times more) in the presence of chloride. While it is well known that GadR is a positive regulator and that the presence of chloride leads to increased gadCB expression in strain MG1363 [35], the molecular mechanisms involved in this expression are not well understood in different L. lactis strains. A more detailed study of the regulation mechanism may provide an explanation for the difference in GAD activity and GABA production in the presence and absence of chloride in this species, and this deserves further attention. However, at the current state of knowledge, phenotypic screening is the best option to identify GABA overproducing strains with potential applications in the natural health product industry.

Conclusions

In this study, combined genotype and phenotype analyses were used to reveal and understand the range of GABA production levels in L. lactis and L. cremoris species. Although all strains possess the gadR, gadC and gadB genes, this does not explain the observed diversity of GABA production, which has multiple causes. Indeed, while genomic polymorphisms may contribute to the non-production of GABA by L. cremoris with the cremoris phenotype, they do not explain the differences in production levels with and without chloride between L. lactis species. The regulatory mechanism of the GAD system that leads to these variations in cellular GAD activity is complex and requires further study.

The addition of chloride may reveal other GABA producers in L. lactis and in L. cremoris with the lactis phenotype species, which are low GABA producers in the absence of chloride.

Overall, these results provide new information on the diversity of GABA production in Lactococcus strains and highlight the richness of this bacterial species for the development of naturally fermented health products.

Abbreviations

- GABA:

-

γ-aminobutyric acid

- LAB:

-

lactic acid bacteria

- L. lactis :

-

Lactococcus lactis

- L. cremoris :

-

Lactococcus cremoris

- GAD:

-

glutamate decarboxylase

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism

- HPLC:

-

high performance liquid chromatography

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

References

Kandler O. Carbohydrate metabolism in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1983;49:209–22.

Ruas-Madiedo P, de los Reyes-Gavilán CG. Invited review: methods for the screening, isolation, and characterization of Exopolysaccharides produced by lactic acid Bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88:843–56.

López-Cuellar Ma del R, Rodríguez-Hernández A-I, Chavarría-Hernández N. LAB bacteriocin applications in the last decade. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equipment. 2016;30:1039–50.

Yang S-C, Lin C-H, Sung CT, Fang J-Y. Antibacterial activities of bacteriocins: application in foods and pharmaceuticals. Front Microbiol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00241.

Chen C, Zhao S, Hao G, Yu H, Tian H, Zhao G. Role of lactic acid bacteria on the yogurt flavour: a review. Int J Food Properties. 2017;20:316–30.

Mazzoli R, Bosco F, Mizrahi I, Bayer EA, Pessione E. Towards lactic acid bacteria-based biorefineries. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32:1216–36.

Vinay-Lara E, Wang S, Bai L, Phrommao E, Broadbent JR, Steele JL. Lactobacillus casei as a biocatalyst for biofuel production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;43:1205–13.

Özcelik S, Kuley E, Özogul F. Formation of lactic, acetic, succinic, propionic, formic and butyric acid by lactic acid bacteria. LWT. 2016;73:536–42.

Sauer M, Russmayer H, Grabherr R, Peterbauer CK, Marx H. The efficient clade: lactic acid Bacteria for Industrial Chemical production. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35:756–69.

Şanlier N, Gökcen BB, Sezgin AC. Health benefits of fermented foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nut. 2019;59:506–27.

Santiago-López L, Aguilar-Toalá JE, Hernández-Mendoza A, Vallejo-Cordoba B, Liceaga AM, González-Córdova AF. Invited review: bioactive compounds produced during cheese ripening and health effects associated with aged cheese consumption. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101:3742–57.

Mathur H, Beresford TP, Cotter PD. Health benefits of lactic acid Bacteria (LAB) fermentates. Nutrients. 2020;12:1679.

Mazzoli R, Pessione E. The Neuro-endocrinological role of Microbial Glutamate and GABA Signaling. Front Microbiol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01934.

Diana M, Quílez J, Rafecas M. Gamma-aminobutyric acid as a bioactive compound in foods: a review. J Funct Foods. 2014;10:407–20.

Chua J-Y, Koh MKP, Liu S-Q. Gamma-aminobutyric acid. In Sprouted Grains 2019 pp. 25–54, Elsevier https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128115251000026.

Laroute V, Beaufrand C, Gomes P, Nouaille S, Tondereau V, Daveran-Mingot M-L, et al. Lactococcus lactis NCDO2118 exerts visceral antinociceptive properties in rat via GABA production in the gastro-intestinal tract. eLife. 2022;11:e77100.

Siragusa S, De Angelis M, Di Cagno R, Rizzello CG, Coda R, Gobbetti M. Synthesis of γ-Aminobutyric acid by lactic acid Bacteria isolated from a Variety of Italian Cheeses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7283–90.

Villegas JM, Brown L, Savoy de Giori G, Hebert EM. Optimization of batch culture conditions for GABA production by Lactobacillus brevis CRL 1942, isolated from quinoa sourdough. LWT - Food Science and Technology. 2016;67:22–6.

Wu Q, Shah NP. High γ-aminobutyric acid production from lactic acid bacteria: emphasis on Lactobacillus brevis as a functional dairy starter. Crit Rev Food Sci Nut. 2017;57:3661–72.

Oliveira LC, Saraiva TDL, Soares SC, Ramos RTJ, Sá PHCG, Carneiro AR, et al. Genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCDO 2118, a GABA-Producing strain. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e00980–14.

Santos-Espinosa A, Beltrán-Barrientos LM, Reyes-Díaz R, Mazorra-Manzano M, Hernández-Mendoza A, González-Aguilar GA, et al. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production in milk fermented by specific wild lactic acid bacteria strains isolated from artisanal mexican cheeses. Ann Microbiol. 2020;70:12.

Redruello B, Saidi Y, Sampedro L, Ladero V, del Rio B, Alvarez MA. GABA-Producing Lactococcus lactis strains isolated from Camel’s milk as starters for the production of GABA-Enriched cheese. Foods. 2021;10:633.

Vo TT-T, Park J-H. Characteristics of potential Gamma-Aminobutyric acid-producing Bacteria isolated from korean and vietnamese fermented Fish Products. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;29:209–21.

Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19126–31.

Passerini D, Beltramo C, Coddeville M, Quentin Y, Ritzenthaler P, Daveran-Mingot M-L et al. Genes but Not Genomes Reveal Bacterial Domestication of Lactococcus Lactis. Ahmed N, editor. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15306.

Caillaud M-A, Abeilhou M, Gonzalez I, Audonnet M, Gaucheron F, Cocaign-Bousquet M, et al. Precise populations’ description in dairy ecosystems using Digital Droplet PCR: the case of L. lactis Group in Starters. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1906.

Li TT, Tian WL, Gu CT. Elevation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris to the species level as Lactococcus cremoris sp. nov. and transfer of Lactococcus lactis subsp. tructae to Lactococcus cremoris as Lactococcus cremoris subsp. tructae comb. nov. IJSEM. 2019;71. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.004727.

Cavanagh D, Casey A, Altermann E, Cotter PD, Fitzgerald GF, McAuliffe O. Evaluation of Lactococcus lactis isolates from Nondairy sources with potential dairy applications reveals extensive phenotype-genotype disparity and implications for a revised species. Schaffner DW, editor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:3961–72.

Wels M, Siezen R, van Hijum S, Kelly WJ, Bachmann H. Comparative genome analysis of Lactococcus lactis indicates Niche Adaptation and resolves Genotype/Phenotype disparity. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:4.

Laroute V, Tormo H, Couderc C, Mercier-Bonin M, Le Bourgeois P, Cocaign-Bousquet M, et al. From genome to phenotype: an Integrative Approach to evaluate the Biodiversity of Lactococcus lactis. Microorganisms. 2017;5:27.

Nomura M, Kimoto H, Someya Y. Novel characteristic for distinguishing Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis from subsp. cremoris. IJSB. 1999;49:163–66.

Reddy MS, Vedamuthu ER, Washam CJ, Reinbold GW. Differential Agar Medium for separating Streptococcus. Appl Microbiol. 1969;18:755–59.

Cotter PD, Hill C. Surviving the Acid Test: responses of Gram-Positive Bacteria to low pH. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:429–53.

Feehily C, Karatzas KAG. Role of glutamate metabolism in bacterial responses towards acid and other stresses. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;114:11–24.

Sanders JW, Venema G, Kok J, Leenhouts K. Identification of a sodium chloride-regulated promoter in Lactococcus lactis by single-copy chromosomal fusion with a reporter gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1998a;257:681–85.

Sanders JW, Leenhouts K, Burghoorn J, Brands JR, Venema G, Kok J. A chloride-inducible acid resistance mechanism in Lactococcus lactis and its regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1998b;27:299–310.

Nomura M, Kobayashi M, Ohmomo S, Okamoto T. Inactivation of the Glutamate Decarboxylase Gene in Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2235–37.

Laroute V, Yasaro C, Narin W, Mazzoli R, Pessione E, Cocaign-Bousquet M, et al. GABA production in Lactococcus lactis is enhanced by arginine and co-addition of Malate. Front Microbiol. 2016;7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01050.

Nouaille S, Mondeil S, Finoux A-L, Moulis C, Girbal L, Cocaign-Bousquet M. The stability of an mRNA is influenced by its concentration: a potential physical mechanism to regulate gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:11711–24.

Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:6.

Nomura M, Kobayashi M, Okamoto T. Rapid PCR-Based Method which can determine both phenotype and genotype of Lactococcus lactis subspecies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2209–13.

Laroute V, Mazzoli R, Loubière P, Pessione E, Cocaign-Bousquet M. Environmental conditions affecting GABA production in Lactococcus lactis NCDO 2118. Microorganisms. 2021;9:122.

Ueno S, Katayama T, Watanabe T, Nakajima K, Hayashi M, Shigematsu T, et al. Enzymatic production of γ-Aminobutyric acid in soybeans using high hydrostatic pressure and precursor feeding. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:706–13.

Huang Y, Su L, Wu J. Pyridoxine Supplementation Improves the Activity of Recombinant Glutamate Decarboxylase and the Enzymatic Production of Gama-Aminobutyric Acid. Bajpai VK, editor. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0157466.

Li H, Qiu T, Huang G, Cao Y. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Lactobacillus brevis NCL912 using fed-batch fermentation. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:85.

Sarasa SB, Mahendran R, Muthusamy G, Thankappan B, Selta DRF, Angayarkanni J. A brief review on the non-protein amino acid, Gamma-amino Butyric Acid (GABA): its production and role in microbes. Curr Microbiol. 2020;77:534–44.

Luo H, Liu Z, Xie F, Bilal M, Liu L, Yang R, et al. Microbial production of gamma-aminobutyric acid: applications, state-of-the-art achievements, and future perspectives. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2021;41:491–512.

Wu Q, Shah NP. Restoration of GABA production machinery in Lactobacillus brevis by accessible carbohydrates, anaerobiosis and early acidification. Food Microbiol. 2018;69:151–8.

Cui Y, Miao K, Niyaphorn S, Qu X. Production of Gamma-Aminobutyric acid from lactic acid Bacteria: a systematic review. IJMS. 2020;21:995.

Romero DA, Klaenhammer TR. Transposable elements in Lactococci: a review. J Dairy Sci. 1993;76:1–19.

Solopova A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. Disruption of a transcriptional repressor by an insertion sequence element integration leads to activation of a Novel Silent Cellobiose Transporter in Lactococcus lactis MG1363. Kivisaar M, editor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e01279–17.

Roces C, Pérez V, Campelo AB, Blanco D, Kok J, Kuipers OP, et al. The putative lactococcal extracytoplasmic function anti-sigma factor Llmg2447 determines resistance to the cell wall-active bacteriocin Lcn972. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5520–7.

Bongers RS, Hoefnagel MHN, Starrenburg MJC, Siemerink MAJ, Arends JGA, Hugenholtz J, et al. IS 981 -Mediated adaptive evolution recovers Lactate production by ldhB transcription activation in a Lactate dehydrogenase-deficient strain of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4499–507.

Gong L, Ren C, Xu Y. Deciphering the crucial roles of transcriptional regulator GadR on gamma-aminobutyric acid production and acid resistance in Lactobacillus brevis. Microb Cell Fact. 2019;18:108.

Wang Q, Liu X, Fu J, Wang S, Chen Y, Chang K, et al. Substrate sustained release-based high efficacy biosynthesis of GABA by Lactobacillus brevis NCL912. Microb Cell Fact. 2018;17:80.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Galaxy Project Team Freiburg for their technical expertise and help with NGS data generation and analysis. The authors also thank the International Centre of Microbial Resources - Food Associated Bacteria (CIRM-BIA, STLO UMR 1253 INRAE-Agrocampus, 65 rue de saint Brieuc, F-35042 Rennes Cedex, France) for providing their strains.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VL and MCB designed the experiments and coordinated the study. VL, NA and MA conducted the experiments. VL, MLDM, MCB, and MMB wrote the initial draft. VL, MLDM and MCB prepared and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1:

Table S1. The 132 studied lactococci with their levels of GABA production, growth rates in media with and without chloride and ability to grow at 40 °C, in 4% (w/v) NaCl and to deaminate arginine.

Additional file 2:

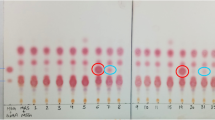

Figure S1. Strain differentiation based on the presence of a 39 bp deletion visualized by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR amplified products *. Lanes: 1, marker size 1 kb, 2, L. cremoris CIRM86, 3, L. cremoris CIRM1563, 4, L. cremoris S72, 5, L. cremoris S73, 6, L. cremoris S74, 7, L. cremoris S75, 8, L. cremoris S76, 9, distilled water, 10, L. cremoris S78, 11, L. cremoris S79, 12, L. cremoris S80, 13, L. cremoris S81, 14, L. cremoris S82, 15, L. cremoris S91, 16, L. cremoris S102, 17, L. cremoris S103, 18, L. cremoris S183, 19, L. cremoris S186, 20, L. lactis IL1403, 21, L. cremoris MG1363, 22, L. lactis NCDO2118, 23, reagent control with DNA, 24, marker size 100 bp.

Additional file 3:

Figure S2. GABA production (mM) after 24 h of growth on glucose-YE medium supplemented with 34 mM L-glutamic acid without NaCl (A) and with 0.3 M NaCl (B) vs. the growth rates of the respective strains (µ in h-1).

Additional file 4:

Table S2. Raw data for gene expression of gadR, gadC, gadB and gene control (tuf).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Laroute, V., Aubry, N., Audonnet, M. et al. Natural diversity of lactococci in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production and genetic and phenotypic determinants. Microb Cell Fact 22, 178 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-023-02181-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-023-02181-4