Abstract

Respiratory self-care places considerable demands on patients with chronic airways disease (AD), as they must obtain, understand and apply information required to follow their complex treatment plans. If clinical and lifestyle information overwhelms patients’ HL capacities, it reduces their ability to self-manage. This review outlines important societal, individual, and healthcare system factors that influence disease management and outcomes among patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—the two most common ADs. For this review, we undertook a comprehensive literature search, conducted reference list searches from prior HL-related publications, and added insights from international researchers and scientists with an interest in HL. We identified methodological limitations in currently available HL measurement tools in respiratory care. We also summarized the issues contributing to low HL and system-level cultural incompetency that continue to be under-recognized in AD management and contribute to suboptimal patient outcomes. Given that impaired HL is not commonly recognized as an important factor in AD care, we propose a three-level patient-centered model (strategies) designed to integrate HL considerations, with the goal of enabling health systems to enhance service delivery to meet the needs of all AD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As the prevalence of chronic diseases continues to increase, along with their burden on health systems and patients [1, 2], there is an increasing awareness that patients will benefit from being empowered to actively engage in disease self-management [3, 4]. This has led to patient-centered care models [5,6,7], which include collaboration between patients and their healthcare providers, and enhanced respect for patient values, preferences and expressed needs [5]. Although a patient-centered approach relies on improving patients’ disease-related knowledge through educational interventions [6, 7], knowledge alone may not sufficiently motivate or enable patients to become active participants in self-management [8, 9]. Patient engagement can be hindered by many factors, including difficulty navigating the healthcare system, misunderstanding information, non-adherence to instructions, and lack of regular, ongoing provider contacts [10,11,12]. Health literacy (HL) has increasingly become recognized as both a cause of and a solution to this problem, as it is a determinant of patient empowerment [13, 14] and disease management success [8, 15,16,17]. Studies among patients with diabetes, cancer, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke have all shown associations between low HL and worse health outcomes [18,19,20]. Unfortunately, despite the importance of HL in self-management of chronic airway diseases (ADs) such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), its application in empowering AD patients to make informed decisions about their health remains limited [11, 16, 21].

Herein, we describe a model for respiratory patient-centered care that is culturally and HL-competent and explore the potential impact of these competencies on care delivery, individuals, and communities. Our goal was to provide a framework and practical approaches that can be applied to improve patient-centered care through HL. To achieve this, we applied insights from the literature and our own practical experiences (including work with national and international HL-focused groups) [22, 23] to suggest strategies to integrate of HL and cultural competency at a system level.

Overview of health literacy

In 2000, Ratzan and Parker [24] defined HL as: “The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” The Canadian Expert Panel on Health Literacy (CEPHL) [25] and the Calgary Charter on Health Literacy [26] developed a model of HL which included five main domains (Table 1) and defined HL as a person’s capability to obtain, understand, communicate, evaluate, and use health information to make appropriate health-related decisions”. The importance of HL for each of these domains has been well established individually [27, 28], and the “five-domain model of HL” has been endorsed and approved by different HL researchers and experts, as essential skills that a person may require to effectively navigate and obtain health information and care services related to their health issues [29, 30]. In addition, an individual’s ability to understand and calculate numerical information (“numeracy”) (Table 1) [31] is a necessary skill for an individual to understand and apply information provided in the health care system. Historically, researchers have considered numeracy to be a HL skill individually [32], however, since numeracy is a variable that is applicable to all core 5 HL domains [33], many researchers assess it across the domains rather than independently [33, 34]. HL is now considered a major determinant of overall health [27, 35,36,37,38], and an essential life skill [37, 39,40,41]. HL is also viewed through a population health lens, as health literate individuals improve the overall health of a community [42, 43]; and as a component of social capital, with low HL contributing to health inequalities [44]. Finally, low HL is associated with increased health care costs [45, 46].

This recognition of the importance of HL has since led to development and testing of several HL measurement tools [47,48,49] for use in healthcare settings:

-

i.

the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM)—a word-recognition assessment [50];

-

ii.

the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA)—involving reading appointment slips, interpreting prescriptions, and filling in missing words on a consent form [51];

-

iii.

the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT)—assessing reading recognition, spelling and basic math skills [52]; and

-

iv.

the Newest Vital Sign (NVS)—assessing reading and numeracy skills through nutrition labels [53].

These tools are brief and relatively easy to administer [54, 55], and previous authors have demonstrated relationships between HL scores on these instruments and outcomes such as disease knowledge, health prevention behaviors, and quality of life, across population groups [56,57,58,59,60]. Accordingly, some have encouraged their use in practice [61, 62]. However, these tools have also been criticized [17, 48, 54, 55] for their focus on general literacy skills [27, 35] rather than skills that define a health literate individual, including navigation, comprehension, motivation and activation, and self-efficacy [16, 63]. In addition, these instruments were developed for the general population, rather than for specific disease groups (which may have disparate needs), and with little or no patient input [48, 64]. Accordingly, many have argued that these existing HL measurement tools have limited validity and applicability in real-world healthcare settings [26, 34, 65,66,67] and emphasized the need for tailored approaches to measuring HL in specific disease populations [28, 36,37,38,39]. Although various such function-based HL measures have since emerged [68,69,70,71,72], their use has not yet been reported in patients with AD. To address this, we brought together patients, HL researchers, and respiratory care clinicians to develop a new function-based HL measurement tool (using realistic case scenarios) exclusively for asthma and COPD patients [68, 73,74,75,76,77], which is currently being validated [78].

Health literacy in respiratory care—an under-recognized problem

Asthma and COPD are among the most common chronic diseases, presenting a major and growing strain on global healthcare resources [21, 46, 79, 80]. Patients with these conditions should be empowered to act as informed decision-makers, develop partnerships with care providers, and self-manage their condition [3, 13, 81]. This requires a high degree of self-efficacy, achieved by obtaining and comprehending information and instructions about their health condition and its treatment [82,83,84,85]. However, patient engagement in such decision-making is dependent on the social determinants of health, including health beliefs and practices, attitudes, cultural norms, socio-economic status (SES), and baseline HL ([39,40,41, 86], Fig. 1).

Accordingly, providers can motivate and empower their patients to engage in disease management by improving their HL skills [83, 86,87,88,89]. The impact of improved HL skills could include slowing disease progression and improving patient-relevant health outcomes [74, 90,91,92]. Although respiratory organizations around the world have recognized the importance of addressing low HL [93,94,95,96,97,98,99] and several AD studies have administered HL measurement instruments, most of these tools focused merely on patient capabilities [8, 15, 16, 46, 100, 101], and were not specific to AD populations [16, 64, 72, 76, 100], thereby, limiting understanding of the impact of low HL on AD health outcomes [14, 15, 67, 102]. Prior investigators have suggested strategies to improve care for patients with low health literacy in clinical settings [5, 22, 37, 103] and some approaches have shown positive results in observational studies [104, 105], but, most of existing studies focus narrowly on educational interventions and corresponding outcomes related to comprehension, inhaler technique, and/or disease knowledge [106,107,108,109]. A previous systematic review [64] did not identify a single AD study that applied all five components of HL as part of an intervention. To gauge the existing state of interest and knowledge surrounding HL in AD, we sought to identify prior experimental and observational studies in ADs that assessed one or more specific component of HL (accessing, communicating, understanding, evaluating, and/or using information to improve disease outcome). These results are summarized in Table 2a–c, demonstrating the characteristics of each reviewed article.

Overall, we summarize 31 articles in this narrative review. None used a disease-specific HL assessment tool, and no single study applied more than three HL domains. The ‘understand’ aspect of HL and improving disease ‘knowledge’ (using knowledge questionnaires) were assessed in all 31 reviewed articles (100%). The ‘use’ domain of HL was identified in 25 articles (81%) of the articles. Use was simply assessed by directly assessing if participants applied the intervention in question (e.g., education) in managing their disease, improving medication adherence, and preventing exacerbations, or by indirectly assessing the impact of the intervention in improving the outcome of interest. ‘Communication’ was the least assessed HL domain, which was identified in only 17 (55%) of the reviewed articles, assessed by measuring the impact of communicating with a health care provider on outcomes of interest. The ‘numeracy’ domain was applied in only two studies (6%), which assessed understanding of numerical concepts such as dose change instructions for self-management of asthma or COPD. Lastly, ‘access’ and ‘evaluation’ domains of HL were each assessed by only one article (3%). Access was assessed by evaluating access barriers to healthcare services and relevant disease management education, and ‘evaluation’ was assessed by measuring patients’ ability to judge the severity of disease symptoms required to initiate needed treatment according to their action plan.

Even when HL was assessed, measurements in individual studies were limited to associations between baseline HL and trial outcomes (e.g., behavioural, healthcare services utilization, and health outcomes) among asthma and COPD patients [90,91,92]. No trial design attempted to improve HL skills through an intervention in order to measure the impact of changes in HL on patient or health system outcomes. For instance, in Azkan Ture et al. study, [110] inadequate HL was more common in patients with severe COPD than those with milder disease. Similarly, several studies demonstrated significant associations between HL and improved self- efficacy (Fan et al. [62]; Martin et al. [82]), and disease control (Wilson et al. [111]; Janson et al. [112]). Others reported correlations between baseline HL and quality of life (Goeman et al. [113]) and Thomas et al. [114]); medication adherence and use (Apter et al. [91]) and (Khdour et al. [115]); hospitalization (Wang et al. [116]), emergency department (ED) visits (Pur Ozyigit et al. [117]), and appropriate response to symptom worsening (Poureslami et al. [84]). Overall, findings consistently showed that patients with low HL skills had lower adherence to their medications and treatment plan, visited the ED more frequently, and had more asthma/COPD-related hospital admissions/re-admissions, and more symptom flare-ups than patients with higher HL skills. Studies also showed that HL was positively correlated with improved non-medical determinants of health. For instance, Eikelenboom et al. [118] found a link between HL levels and adopting healthier nutrition and having improved patient activation levels. Other researchers found significant associations between HL skills and exercise capacity (Wang et al. [116]), smoking cessation (Efraimsson et al. [119], and medical decision making (Wang et al. [90]. Despite these promising results, the mechanisms behind the reported associations between HL and respiratory outcomes remain unclear, as we did not identify any interventional studies that sought to enhance HL and measure impact on outcomes (e.g. inhaler technique, awareness and control of symptoms, management of acute exacerbation, and proper use of healthcare services). Accordingly, the causal relationship between HL and health outcomes requires further investigation [23, 101, 120].

Patient HL challenges and potential respiratory care system responses

In the following section, we highlight challenges faced by patients with AD and low HL in actively engaging in disease management, and practice- and system-level changes required to address these barriers and drive improvements in HL.

Accessing health information and services

Limited access includes both the availability and attainability of information and services [121, 122]. Disadvantaged individuals experience inadequate access for several reasons [58, 104]; (1) they have less regular primary care visits [11, 118, 123]; (2) they are more prone to accessing healthcare information from unreliable sources outside of the medical system (e.g. a friend with a "similar" health condition, family members, neighbors, or the internet) [10, 23, 84, 102]; (3) even when referred to specialty clinics (including respiratory clinics), these settings are particularly poorly suited to offering culturally sensitive and/or same-language care to patients of diverse backgrounds [123,124,125,126,127,128].

Given that culturally matched patient-provider interactions have been shown to augment patient engagement in disease management and to improve health outcomes [125, 126, 129, 130], healthcare systems must invest in improving competencies and diversity of personnel (language and cultural) in order to render all care services attainable to all members of the community [2, 30, 102, 105]. This can be supplemented by provision of multi-lingual health information (written and/or electronic) that is also easily understandable and relevant across ethnicities and cultures.

Processing and understanding information and instructions

Respiratory care providers often overestimate patients’ HL skills, assuming that complex instructions have been understood [32, 132]. This issue is compounded by the fact that many patients with limited HL also overestimate their own ability to process and understand medical instructions [61, 111, 133]. In addition to verbal communication, printed disease-related educational materials are often inaccessible to low HL patients due to an inappropriately high reading grade requirement for comprehension [23, 93, 97, 128, 134] (low HL and low literacy and reading skills are closely associated [8, 9, 135, 136]).

To address these issues, both care and accompanying educational materials must be tailored to the diverse needs and abilities of patients across different ethnic and cultural communities, ages, and socioeconomic classes [90, 137, 138]. A suggested approach to foster open, interactive patient-provider communication is to compliment plain language resources [56, 132, 139, 140] with a “teach back” approach (asking the patient to repeat back what was understood), to ensure that patients have understood information correctly [141, 142], stimulating dialogue and question-asking [143]. This approach has been shown to improve medication adherence and inhaler technique in AD patients [133, 144, 145]. Patient input in material development can help to ensure that reading levels and content are properly matched to the target audience, and optimize both content and layout, thereby enhancing understanding and uptake [118, 137, 144, 146]. Specifically, incorporation of patient input in self-management tools for asthma and COPD augments self-management behaviors and improves outcomes, particularly in older patients [92, 113, 145, 147].

Appraising the quality of information and care services

To optimize health outcomes, AD patients must assess the quality and credibility of health information they encounter, and its relevance to their personal health needs [23, 87, 148].

Lacking corresponding critical appraisal and evaluation skills has emerged as a central issue in HL research in recent years [149, 150], but has barely been studied in respiratory research [66, 87, 149]. Accurate measurement of evaluation skills could help to identify the differences between patients’ expectations and their perceptions of the services and information received [61]. This evaluation skill component of HL is understudied, particularly in AD [68, 78].

Applying information to make health-related decisions

Most attention in HL research has been focused on information availability, accessibility, and comprehension (readiness, attainability, readability, and comprehensibility of health-related information) [48, 58, 63]. However, maintaining health requires a series of practical acts, and obtaining and understanding relevant information does not equate to using it [114, 151]. Although all aspects of HL are important, the effectiveness of health information and services in changing behavior is what ultimately determines impact [17, 25]. Many patients with airways diseases have high levels of knowledge about their health condition [23, 120, 137, 148], but struggle to apply that knowledge in the disease management process [11, 12, 27, 107, 125, 135]. A person’s behaviours are also influenced by internal and external motivations, as well as their ability, readiness, and willingness to use the information received from care providers [19, 60, 102, 140, 147]. Additionally, factors such as beliefs and worldviews, the perceived trustworthiness and practicability/relevance of the information, and previous experiences all effects a person’s intention to apply the information [77, 78, 92, 152]. Accordingly, patient-provider interactions must go beyond information “transfer”, to facilitate behavior change [133, 140]. Improving patient educational materials to include personalized instructions (both related to the behaviour itself and how to achieve the behaviour change) may empower patients with the skills needed to change [90, 117, 139, 153]. Additionally, when appropriate, providers may augment this process by having patients practice relevant actions and procedures (and offer feedback) to compliment and reinforce verbal and written information [56, 132, 154].

A model for health literacy and culturally competent respiratory care

Both cultural and social factors deeply influence the way people access and navigate health information and services [2, 41, 127, 155]. Culturally competent care systems understand and respect the health beliefs and practices of their patients, appreciate language barriers, and apply such understanding in practice [126, 134, 156,157,158]. Accordingly, HL competent care facilitates equity of essential healthcare services for all community members [14, 37,38,39,40,41, 103]. Increasing diversity in healthcare providers themselves (including in leadership and governance) and use of patient navigators (trained health workers) to assist vulnerable patients with language and/or literacy barriers may help to address system inequities [102, 159]. However, implementation of these strategies may be hindered by various countries’ population structures (i.e. a lack of sufficient representatives to play these roles across diverse cultural and language groups) [134, 160].

A three-level model

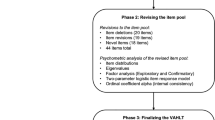

Patients with AD, particularly older patients and COPD patients are among population groups with the lowest HL levels [92, 145, 147]. To achieve the goal of creating a responsive, patient-centered system of care for AD patients, we propose new strategies, in a three-level model format (Fig. 1), with special focus on training and empowering healthcare professionals to excel in roles as change agents for bridging cultural and HL gaps in their own patients [161]. The change agents can also leverage rapidly accelerating virtual care and communication technologies to address inequitable access to health information and care; and the last is to broaden the healthcare services team by building partnerships with (culturally competent) community stakeholders [162, 163]. We applied the three-level model strategies in our recent research projects [10, 15, 68, 84, 125, 128, 130, 146, 164, 165]. The results of our studies demonstrated potential efficacy of the proposed strategies and the need for further prospective validation. These strategies and their expected outcomes are outlined below.

Firstly, respiratory clinics should train providers to recognize the heterogeneity in patients’ beliefs, preferences, limits, and needs, and consider these in their communication style and clinical practices [102, 157, 162, 163]. There is evidence that improved provider communication skills and awareness of social determinants of health mitigate impacts of limited HL and cultural mismatch [86, 157, 166]. With appropriate training (in university for future health professionals and through ongoing/continued education for current staff), respiratory health professionals can acquire the skills required to act as change agents [167], by engaging in patient questions, explaining treatment instructions while avoiding medical jargon, and using strategies such as the teach-back method [108, 140, 166]. The focus of a change agent is to improve a patient's capacity and motivation to engage in self-management (one of the foundational components of AD management). Given the impact of social determinants of health [161], this role may extend beyond medical practice to a global assessment and support of financial and social factors impacting adherence, motivation, and treatment response [102, 168]. This approach has been shown to improve self-management and outcomes in this population [3, 88, 89, 92, 145, 154]. However, a sustainable model will require advocacy regarding the importance of non-medical determinants of health in respiratory disease management [169] to ensure that these aspects are included in future curricula and programming, and receive sufficient funding.

Secondly, to address disparate and inequitable access to health information and services, respiratory care providers must espouse emerging technology, in the form of virtual communication and care strategies. The goal is to overcome care access barriers related specifically to patients living in remote or rural areas and/or having difficulties securing time away from work for appointments during normal office hours [121, 164, 170,171,172,173]. With technological advancements as well as increased provider and patient acceptance of and access to remote communication models driven by the COVID-19 pandemic [174, 175] (even among lower socioeconomic class groups), telehealth can now be used to address essential healthcare services across patient populations [173]. It can also facilitate health education for patients and communication between primary care physicians and specialists [176, 177]. Although telehealth-based interventions improved knowledge [176], emotional and mental health [173], quality of life [172], medication adherence [178], hospitalization and emergency department (ED) visits [179], and self-monitoring [176, 178] across chronic diseases, there are no high-quality studies evaluating this in AD [177]. Ideas such as an electronically accessible action plan with weekly text message reminders to assess one’s asthma control [165], and virtual pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) (telerehab) [172, 180] hold promise [181]. For example, a telerehab program can provide educational materials online, with the patient attending practical sessions (e.g., exercise, breathing/cough control training) via interactive video conferencing [180, 181]. Such a program was shown to improve exercise capacity, health related quality of life, and psychological status [180, 181]. This approach also enables access for those living in remote locations and whose physical limitations and/or capacity to secure transit impairs in-person attendance [180]. In fact, virtual care is often favored by patients and providers alike due to convenience and flexibility [174].

Finally, a successful model must build partnerships with community stakeholders (patients, community leaders, and opinion leaders). Partnerships lead to allyship—through insights into the challenges faced by community members in accessing and navigating health services [82, 118]. This can occur as part of community care, or, for example, community AD patients might be involved in participatory research (from the beginning of the research process) and/or in developing educational material [82, 118, 131, 164]. For example, we successfully gauged AD patients’ research priorities through a series of focus groups across Canada [10, 73, 84, 146, 182] and applied these in the Canadian Respiratory Research Network’s research prioritization exercise (https://respiratoryresearchnetwork.ca/). We also engaged patients, community healthcare providers, and clinicians in developing audio-visual educational materials on AD topics in seven different languages [125, 128, 130, 163, 183]. This work enabled us to establish a peer-support network [127] that offers newly diagnosed patients with AD the opportunity to gain insights from those with lived experience in managing AD [184, 185]. These groups also provided an opportunity for individuals of diverse cultural backgrounds and HL levels to interact with others in a familiar language and at a comparable level of sophistication. Such peer support and patient networks have been shown to reduce patients’ feelings of isolation and fear, to enhance their mental capacity to cope with their condition, and to build the confidence needed to engage in self-management [132, 184,185,186]. Care system-community collaboration has also been shown to facilitate delivery of effective education to disadvantaged patients [1, 11, 68, 111, 185, 187, 188].

Conclusions

As patients with AD are increasingly expected to actively engage in disease self-management, we must acknowledge the responsibility of the health system to ensure that they have the capacity to execute such complex tasks, by addressing their HL [30, 37, 41, 105, 171]. A respiratory care system that reinforces HL in a culturally competent way will improve health outcomes through patient engagement, clearer communication, and improved patient-provider interactions. Key components of system change include training healthcare providers to become change agents, accelerating adoption of evidence-based virtual communication and care strategies, and building partnerships with community stakeholders. These changes will reduce socio-cultural and socio-economic disparities in care access and quality, yielding enormous benefits for patient outcomes, possibly with reductions in healthcare costs [46].

There are exciting research opportunities to design and evaluate novel strategies to both measure HL and to address cultural competency and HL in patients with AD. Longitudinal research is particularly needed to evaluate which health outcomes are improved by addressing HL in a culturally competent way, including the sustainability of observed effects. As communication technologies continually advance, research is also needed to determine the most efficient and effective strategies to enable virtual care. Ultimately, our common goal should be to realize a patient-centered respiratory care system that engages willing patients not only in decision-making around their own care, but also in the development of the very educational material that is presented to them and the very research, which establishes their therapy.

Availability of data and materials

The authors have made readily reproducible materials described in the manuscript, including the software used, databases and all relevant raw data, and made them freely available to any scientist wishing to use them, without breaching participant confidentiality.

Abbreviations

- HL:

-

Health literacy

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- AD:

-

Airway disease

- PR:

-

Pulmonary rehabilitation

References

Hajat C, Stein E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: a narrative review. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:284–93.

Michener JL, Briss P. Health systems approaches to preventing chronic disease: new partners, new tools, and new strategies. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16: 190248. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.190248.

Pulvirenti M, McMillan J, Lawn S. Empowerment, patient-centered care and self-management. Healthy Expect. 2014;17(3):303–10.

McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20093.

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(4):351–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712465774.

van der Eijk M, Nijhuis FA, Faber MJ, Bloem BR. Moving from physician-centered care towards patient-centered care for Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(11):923–7.

Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Bello-Haas WA, Law M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:271–80.

van der Heide I, Wang J, Droomers M, et al. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: results from the Dutch Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. J Health Commun. 2013;18:172–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.825668.

Schillinger D, Barton LR, Karter AJ, et al. Does literacy mediate the relationship between education and health outcomes? A study of a low-income population with diabetes. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(3):245–54.

Poureslami I, Pakhale S, Lavoie KL, et al. Patients as research partners in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma research: priorities, challenges and recommendations from asthma and COPD patients. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2018;2(3):138–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2018.1443294.

Russell S, Ogunbayo OJ, Newham JJ, et al. Qualitative systematic review of barriers and facilitators to self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: views of patients and healthcare professionals. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2018;28(2):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0069-z.

Jerant AF, Friederichs-Fitzwater MM, Moore M. Patients’ perceived barriers to active self-management of chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:300–7.

Crondahl K, Karlsson LE. The nexus between health literacy and empowerment: a scoping review. SAGE Open. 2016, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016646410

FitzGerald JM, Poureslami I. The need for humanomics in the era of genomics and the challenge of chronic disease management. Chest. 2014;146(1):10–2. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-2817.

Poureslami I, Rootman I, Pleasant A, FitzGerald JM. The emerging role of health literacy in chronic disease management: the response to a call for action in Canada. Popul Health Manag. 2016;19(4):230–1. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2015.0163.

Shum J. The role of health literacy in chronic respiratory disease management. Master’s Thesis-Experimental Medicine. University of British Columbia, Canada. 2017. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0357228. Accessed 9 Sep 2022.

Duell P, Wright D, Renzaho AD, Bhattacharya D. Optimal health literacy measurement for the clinical setting: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(11):1295–307.

Aran N, Tregobov N, Poureslami I, et al. Health literacy and health outcomes in stroke management: a systematic review and evaluation of available measures. Hum Soc Sci. 2022;5(2):172–91.

Husson O, Mols F, Fransen MP, et al. Low subjective health literacy is associated with adverse health behaviors and worse health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors: Results from the profiles registry. Psychooncology. 2015;24(4):478–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3678.

Caplan L, Wolfe F, Michaud K, et al. Strong association of health literacy with functional status among rheumatoid arthritis patients: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66(4):508–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22165.

Salim H, Ramdzan SN, Ghazali SS, et al. A systematic review of interventions addressing limited health literacy to improve asthma self-management. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1): 010427. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010428.

Poureslami I, Nimmon L, Rootman I, FitzGerald JM. Priorities for action: recommendations from an international roundtable on health literacy and chronic disease management. Health Promot Int. 2017;32:743–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw003.

Poureslami I, Nimmon L, Shum J, FitzGerald JM. Hearing community voice: methodological issues in developing asthma self-management educational materials for immigrant communities. NY: NOVA Publisher; 2013.

Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction, in National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy; Ratzan SC, Parker RM, Selden CR, Zoern M Editor. Bethesda: NLM Pub. 2000

Rootman I, Gordon-El-Bihbety D. A vision for a health literate canada report of the expert panel on health literacy. Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association; 2008.

Pleasant A, Maish C, O’Leary C, Carmona RH. A theory-based self-report measure of health literacy: the Calgary Charter on Health Literacy scale. Methodological Innovations. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799118814394.

Jordan JE, Buchbinder R, Briggs AM, et al. The health literacy management scale (HeLMS): a measure of an individual’s capacity to seek, understand and use health information within the healthcare setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):228–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.013.

Jordan JE, Osborne RH, Buchbinder R. Critical appraisal of health literacy indices revealed variable underlying constructs, narrow content and psychometric weaknesses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):366–79.

Mitic W, Rootman I. An inter‐sectoral approach for improving health literacy for Canadians—a discussion paper. Public Health Association of BC. 2012. http://www.cpha.ca/uploads/portals/h-l/intersectoral_e.pdf. Accessed 1 Jun 2016.

Pleasant A. Advancing health literacy measurement: a pathway to better health and health system performance. J Health Commun. 2014;19(12):1481–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.954083.

Golbeck AL, Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Paschal AM, et al. A definition and operational framework for health numeracy. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(4):375–6.

Altin SV, Finke I, Kautz-Freimuth S, Stock S. The evolution of health literacy assessment tools: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1207–20.

Griffey RT, Melson AT, Lin MJ, et al. Does numeracy correlate with measures of health literacy in the emergency department? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12310.

Kiechle ES, Bailey SC, Hedlund LA, et al. Different measures, different outcomes? A systematic review of performance-based versus self-reported measures of health literacy and numeracy. J Gen Internal Med. 2015;30(10):1538–46.

Pleasant A, Rudd RE, O’Leary C, et al. Considerations for a new definition of health literacy. Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. 2016. Available from: http://nam.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/04/Considerations-for-a-New-Definition-of-Health-Literacy.pdf. Accessed 24 Jul 2022.

Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(12):2072–8.

Rudd RE. The evolving concept of health literacy: new directions for health literacy studies. J Commun Healthc. 2015;8(1):7–9. https://doi.org/10.1179/1753806815Z.000000000105.

Kickbusch I. Health literacy: an essential skill for the twenty-first century. Health Educ. 2008;108(2):101–4. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280810855559.

Lastrucci V, Lorini C, Caini S, Bonaccorsi G. Health literacy as a mediator of the relationship between socioeconomic status and health: a cross-sectional study in a population-based sample in Florence. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12): e0227007. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227007.

Pelikan JM, Ganahl K, Roethlin F. Health literacy as a determinant, mediator and/or moderator of health: empirical models using the European Health Literacy Survey dataset. Glob Health Promot. 2018;25(4):57–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975918788300.

Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(Suppl):S8-17. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42.

Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80–93.

Gazmararian JA, Curran JW, Parker RM, et al. Public health literacy in America: an ethical imperative. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(3):317–22.

Sentell T, Pitt R, Buchthal OV. Health literacy in a social context: review of quantitative evidence. Health Lit Res Pract. 2017;1(2):e41–70.

Pawlak R. Economic considerations of health literacy. Nurs Econ. 2005;23(4):173–80.

Ture DZ, Demirci H, Dikis OS. The relationship between health literacy and disease specific costs in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Aging Male. 2020;23(5):396–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13685538.2018.1501016.

Stagliano V, Wallace LS. Brief health literacy screening items predict newest vital sign scores. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(5):558–65. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2013.05.130096.

Kronzer VL. Screening for health literacy is not the answer. BMJ. 2016;354: i3699. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3699.

Bass PF III, Wilson JF, Griffith CH. A shortened instrument for literacy screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:1036–8.

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine( REALM): a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–5.

Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The Test of Functional health literacy in adults (TOFHLA): a new instrument for measuring patient’s literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–42.

Jastak S, Wilkinson GS, Jastak Associates. WRAT-R: wide range achievement test, Administration manual. Revised. Wilmington: Jastak Assessment Systems; 1984.

Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign NVS). Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514–22. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.405.

Haun J, Luther S, Dodd V, Donaldson P. Measurement variation across health literacy assessments: implications for assessment selection in research and practice. J Health Commun. 2012;17:141–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.712615.

Haun JN, Valerio MA, McCormack LA, et al. Health literacy measurement: an inventory and descriptive summary of 51 instruments. J Health Commun. 2014;19(Sup2):302–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.936571.

Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, et al. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician–patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(3):315–523.

Ishikawa H, Takeuchi T, Yano E. Measuring functional, communicative, and critical health literacy among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:874–9.

Stormacq C, Wosinski J, Boillat E, Van den Broucke S. Effects of health literacy interventions on health-related outcomes in socioeconomically disadvantaged adults living in the community: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(7):1389–469. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-D-18-00023.

Visscher BB, Steunenberg B, Heijmans M, et al. Evidence on the effectiveness of health literacy interventions in the EU: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1414. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6331-7.

Walters R, Leslie SJ, Polson R, et al. Establishing the efficacy of interventions to improve health literacy and health behaviours: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1040. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08991-0.

Schulz PJ, Pessina A, Hartung U, Petrocchi S. Effects of objective and subjective health literacy on patients’ accurate judgment of health information and decision-making ability: survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e20457.

Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:673–83.

Dowse R. The limitations of current health literacy measures for use in developing countries. J Commun Healthc. 2016;9(1):4–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2016.1147742.

Shum J, Poureslami I, Wiebe D, et al. Airway diseases and health literacy (HL) measurement tools: a systematic review to inform respiratory research and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(4):596–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.011.

Institute of Medicine (IOM) Roundtable on Health Literacy. Measures of Health Literacy: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. 2, An Overview of Measures of Health Literacy. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45375/. Accessed 2 Jul 2022.

Papp-Zipernovszky O, Csabai M, Schulz PJ, Varga JT. Does health literacy reinforce disease knowledge gain? A prospective observational study of hungarian COPD patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10(17):3990. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10173990.

FitzGerald JM, Poureslami I. Chronic disease management: a proving ground for health literacy. Popul Health Manag. 2014;17(6):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2014.0078.

Poureslami I, Shum J, Kopec J, et al. Development and pretesting of a new functional-based health literacy measurement tool for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma management. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:613–25. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S234418.

Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, et al. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38:33–42.

Sorensen K, Van Den Broucke S, Pelikan JM, et al. Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health. 2013;13:948–59.

Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, et al. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2013;13:658–69.

Sun X, Chen J, Shi Y, et al. Measuring health literacy regarding infectious respiratory diseases: a new skills-based instrument. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64153. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064153.

Poureslami I, Shum J, Boulet PL, et al. Involvement of patients and professionals in the development of a conceptual framework on functional health literacy to improve chronic airways disease outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A4623.

Poureslami I, Shum J, Goldstein RS, et al. Asthma and COPD patients’ perceived link between health literacy core domains and self-management of their condition. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(7):1415–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.02.011.

Ven Der Hiede I, Poureslami I, Mitis W, et al. Health literacy in chronic disease management: A matter of interaction. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018; 102: 134–138

Shum J, Poureslami I, Wiebe D, et al. Bridging the gap: Key informants’ perspectives on patient barriers in asthma and COPD self-management and possible solutions. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2020;4(2):106–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2019.1582307.

Poureslami I, Kopec J, Tregobov N, et al. An integrated framework to conceptualize and develop the Vancouver airways health literacy tool (VAHLT). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8646–62. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168646.

Poureslami I, Tregobov N, Shum J, et al. A conceptual model of functional health literacy to improve chronic airway disease outcomes. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):252. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10313-x.

Myers TR. Guidelines for asthma management: a review and comparison of 5 current guidelines. Respir Care. 2008;53:751–69.

Steurer-Stey C, Dalla Lana K, Braun J, et al. Effects of the “Living well with COPD” intervention in primary care: a comparative study. Eur Respir J. 2018;51:1701375.

Sadeghi S, Brooks D, Stagg-Peterson S, Goldstein R. Growing awareness of the importance of health literacy in individuals with COPD. COPD. 2013;10(1):72–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2012.727919.

Martin MA, Catrambone CD, Kee BA, et al. Improving asthma self-efficacy: Developing and testing a pilot community-based asthma intervention for African American adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(1):153-159.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.057Kiser.

Jonas KD, Warner Z, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a literacy-sensitive self-management intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(2):190–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1867-6.

Poureslami I, Kwan S, Lam S, et al. Assessing the effect of culturally-specific educational interventions on attaining self-management skills for COPD in Mandarin and Cantonese speaking patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;3(11):1811–22.

Thom DH, Willard-Grace R, Tsao S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of health coaching for vulnerable patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(10):1159–68. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201806-365OC.

Andermann A. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016;188(17–18):E474–83.

Londono AM, Schulz PJ. Influences of health literacy, judgment skills, and empowerment on asthma self-management practices. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:908–17.

Mola E, De Bonis JA, Giancane R. Integrating patient empowerment as an essential characteristic of the discipline of general practice/family medicine. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14(2):89–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814780802423463.

Disler RT, Appleton J, Smith TA, et al. Empowerment in people with COPD. Patient Intell. 2016;8:7–20.

Wang KY, Chu NF, Lin SH, et al. Examining the causal model linking health literacy to health outcomes of asthma patients. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(13–14):2031–42.

Apter AJ, Wan J, Reisine S, et al. The association of health literacy with adherence and outcomes in moderate-severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):321–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.014.

Federman AD, Wolf M, Sofianou A, et al. The association of health literacy with illness and medication beliefs among older adults with asthma. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(2):273–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.013.

American Thoracic Society Guidelines for Patient Education Materials. Editorial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1208–11.

2022 Global initiatives for asthma (GINA) Report: Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2022.

Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman RD, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: asthma control and exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:59–99.

Blackstock FC, Lareau SC, Nici L, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease education in pulmonary rehabilitation. An Official American Thoracic Society/Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand/Canadian Thoracic Society/British Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(7):769–84. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-253WS.

American Thoracic Society. Patient education materials development: guidelines for the ATS (P-GATS). New York, NY: American Thoracic Society; 2015. https://www.thoracic.org/patients/pgats.php. Accessed 1 May 2022.

2022 Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD. file:///C:/Users/HLAnalyst/Downloads/GOLD-REPORT-2022-v1.1–22Nov2021_WMV%20(1).pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2022.

Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–46. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.04.00014304.

Shnaigat M, Downie S, Hosseinzadeh H. Effectiveness of health literacy interventions on COPD self-management outcomes in outpatient settings: a systematic review. COPD. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2021.1872061.

Jeganathan C, Hosseinzadeh H. The role of health literacy on the self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. COPD. 2020;8:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2020.1772739.

Shum J, Poureslami I, Cheng N, FitzGerald JM. Responsibility for COPD self-management in ethno-cultural communities: The role of patient, family member, care provider, and system. Divers Equal Health Care. 2014;11:201–13.

Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15:259–67.

Galbreath AD, Smith B, Wood PR, et al. Assessing the value of disease management: impact of 2 disease management strategies in an underserved asthma population. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(6):599–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60222-0.

World Health Organization. Everybody business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action 2007. Printed by the WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland. ISBN 978 92 4 159607 7. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2022.

Press VG, Arora VM, Trela KC, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to teach metered-dose and diskus inhaler techniques. A randomized trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(6):816–24.

Abley C. Teaching elderly patients how to use inhalers. A study to evaluate an education programme on inhaler technique for elderly patients. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:699–708.

Alsomali HJ, Vines DL, Stein BD, Becker EA. Evaluating the effectiveness of written dry powder inhaler instructions and health literacy in subjects diagnosed with COPD. Respir Care. 2017;62(2):172–8. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.04686.

Beatty CR, Flynn LA, Costello TJ. The impact of health literacy level on inhaler technique in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190015585759.

Azkan Ture D, Bhattacharya S, Demirci H, Yildiz T. Health literacy and health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: an explorative study. Front Public Health. 2022;10: 846768. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.846768.

Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, et al. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(6):566–77. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200906-0907OC.

Janson SL, McGrath KW, Covington JK, et al. Individualized asthma self-management improves medication adherence and markers of asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(4):840–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.053.

Goemanab D, Jenkinsc C, Cranec M, et al. Educational intervention for older people with asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(3):586–95.

Thomas RM, Locke ER, Woo DM, et al. Inhaler training delivered by internet-based home video-conferencing improves technique and quality of life. Respir Care. 2017;62(11):1412–22. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.05445.

Khdour MR, Kidney JC, Smyth BM, McElnay JC. Clinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPD. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:588–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-2125.2009.03493.x.

Wang LH, Zhao Y, Chen LY, et al. The effect of a nurse-led self-management program on outcomes of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Respir J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.13112.

Pur Ozyigit L, Ozcelik B, Ciloglu SO, Erkan F. The effectiveness of a pictorial asthma action plan for improving asthma control and the quality of life in illiterate women. J Asthma. 2014;51:423–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2013.863331.

Eikelenboom N, van Lieshout J, Jacobs A, et al. Effectiveness of personalised support for self-management in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(646):e354–61.

Efraimsson EO, Hillervik C, Ehrenberg A. Effects of COPD selfcare management education at a nurse-led primary health care clinic. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(2):178–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00510.x.

Yadav UN, Lloyd J, Hosseinzadeh H. Do Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) self-management interventions consider health literacy and patient activation? a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9030646.

MacKichan F, Brangan E, Wye L, et al. Why do patients seek primary medical care in emergency departments? An ethnographic exploration of access to general practice. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e013816. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013816.

Anarella J, Roohan P, Balistreri E, Gesten F. A survey of Medicaid recipients with asthma: perceptions of self-management, access, and care. Chest. 2004;125(4):1359–67. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.4.1359.

Kang M, Robards F, Luscombe G, et al. The relationship between having a regular general practitioner (GP) and the experience of healthcare barriers: a cross-sectional study among young people in NSW, Australia, with oversampling from marginalized groups. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:220–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-01294-8.

Poureslami I, Shum J, Nimmon L, FitzGerald JM. Culturally specific evaluation of inhaler techniques in asthma. Respir Care. 2016;61(12):1588–96. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.04853.

Shum M, Poureslami I, Liu J, Fitzgerald JM. Perceived barriers to asthma therapy in ethno-cultural communities: the role of culture beliefs and social support. Health. 2017;9(7):1029–46.

Zanchetta SZ, Poureslami I. Health literacy within the reality of immigrants’ culture and language. Can J Public Health. 2006;97(3):S26–30.

Lie D, Carter-Pokras O, Braun B, Coleman C. What do health literacy and cultural competence have in common? Calling for a collaborative health professional pedagogy. J Health Commun. 2012;17:13–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.71262.

Poureslami I, Nimmon L, Doyle-Waters M, FitzGerald JM. Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) with ethno-cultural groups as a tool to develop culturally and linguistically appropriate asthma educational materials. J Divers Health Care. 2012;8(4):203–15.

Poureslami I, Rootman I, Balka E, et al. A systematic review of asthma and health literacy: a cultural-ethnic perspective in Canada. MedGenMed. 2007;9(3):40–54.

Poureslami I, Nimmon L, Doyle-Waters M, et al. Effectiveness of educational interventions on asthma self-management in Punjabi and Chinese asthma patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Asthma. 2012;49(5):542–51. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2012.682125.

Chapman KR, Hinds D, Piazza P, et al. Physician perspectives on the burden and management of asthma in six countries: the Global Asthma Physician Survey (GAPS). BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17:153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0492-5.

Quirt CF, Mackillop WJ, Ginsburg AD, et al. Do doctors know when their patients don’t? A survey of doctor-patient communication in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 1997;18:1–20.

Sadeghi S, Brooks D, Goldstein RS. Patients’ and providers’ perceptions of the impact of health literacy on communication in pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis. 2012;10(2):65–76.

Commonwealth of Australia. Cultural competency in health: a guide for policy, partnerships and participation. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, National Health and Medical Research Council; 2006.

Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS, Nurss J. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health. 1997. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.87.6.1027.

Nutbeam D. Defining and measuring health literacy: what can we learn from literacy studies? Int J Public Health. 2009;54:303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0050-x.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(8):980–6.

Thoonen BP, Schermer TR, Jansen M, et al. Asthma education tailored to individual patient needs can optimise partnerships in asthma self-management. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47(4):355–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00015-0.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plain language materials and resources. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/developmaterials/plainlanguage.html. Accessed 23 Sep 2022.

Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: a conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(5):777–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198106291963.

Dantic DE. A critical review of the effectiveness of ‘teach-back’ technique in teaching COPD patients self-management using respiratory inhalers. Health Educ J. 2014;73(1):41–50.

Peter D, Robinson P, Jordan M, et al. Reducing readmissions using teach-back. JONA. 2015;45(1):35–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000155.

Ha D, Bonner A, Clark R, et al. The effectiveness of the teach-back method on adherence and self-management in health education for people with chronic disease: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(1):210–47.

Heijmans M, Waverijn G, Rademakers J, et al. Functional, communicative and critical health literacy of chronic disease patients and their importance for self-management. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:41–8.

Federman AD, O’Conor R, Mindlis I, et al. Effect of a self-management support intervention on asthma outcomes in older adults: the SAMBA study randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1113–21. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1201.

Poureslami I, Camp P, Shum J, et al. Using exploratory focus groups to inform the development of a peer-supported pulmonary rehabilitation program: direction for further research. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2017;37(1):57–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000213.

Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):204–11.

American Lung Association. The 4th annual Respiratory Patient Advocacy Summit. Patient Voices Heard at Respiratory Patient Advocacy Summit. AARC Congress 2018. Available from: https://www.monaghanmed.com/patient-voices-heard-respiratory-patient-advocacy-summit/. Accessed 17 Jun 2022.

Londoño AM, Schulz PJ. Judgment skills, a missing component in health literacy: development of a tool for asthma patients in the Italian-speaking region of Switzerland. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-3258-72-12.

Londoño AM, Schulz PJ. Impact of patients’ judgment skills on asthma self-management: a pilot study. J Public Health Res. 2014;3(3):307–12. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2014.307.

Mackey LM, Doody C, Werner EL, Fullen B. Self-management skills in chronic disease management: what role does health literacy have? Med Decis Making. 2016;36(6):741–59.

Agarwal P, Lin J, Muellers K, et al. A structural equation model of relationships of health literacy, illness and medication beliefs with medication adherence among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(6):1445–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.024.

Gupta S, Tan W, Hall S, Straus SE. An asthma action plan created by physician, educator and patient online collaboration with usability and visual design optimization. Respiration. 2012;84(5):406–15. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338112.

Wakabayashi R, Motegi T, Yamada K, et al. Efficient integrated education for older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11(4):422–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00696.x.

Zamir, D. Culturally appropriate HealthCare by culturally competent health professionals: community Intervention for Diabetes Control Among Adult Arab Population. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&q=%22community+intervention+for+diabetes+control+among+adult+arab+population%22. Accessed 30 Sep 2022.

Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(11):1275–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31505-4.

Lie DA, Lee-Rey E, Gomez A, et al. Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):317–25.

Butler M, McCreedy E, Schwer N, et al. Improving Cultural Competence to Reduce Health Disparities [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 Mar. (Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 170.) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK361126/. Accessed 19 Oct 2022.

McBrien KA, Ivers N, Barnieh L, et al. Patient navigators for people with chronic disease: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2): e0191980. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191980.

Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE. Cultural competence in health care: Emerging framework and practical approaches. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2002. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2002_oct_cultural_competence_in_health_care__emerging_frameworks_and_practical_approaches_betancourt_culturalcompetence_576_pdf.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2022.

Alagoz E, Chih MY, Hitchcock M, et al. The use of external change agents to promote quality improvement and organizational change in healthcare organizations: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2856-9.

Ogrodnick MM, Feinberg I, Tighe E, et al. Health-literacy training for first-year respiratory therapy students: a mixed-methods pilot study. Respir Care. 2020;65(1):68–74. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.06896.

Betancourt J, Green A. Commentary: linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes: perspectives from the field. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):583–5.

Murphy D, Balka E, Poureslami I. Communicating health information: the community engagement model for video production. Can J Commun. 2007;32(3):121–34.

Poureslami I, Shum J, Lester RT, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial on the impact of text messaging check-ins and a web-based asthma action plan versus a written action plan on asthma exacerbations. J Asthma. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2018.1500583.

Noordman J, Schulze L, Roodbeen R, et al. Instrumental and affective communication with patients with limited health literacy in the palliative phase of cancer or COPD. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00658-2.

Rickards T, Kitts E. The roles, they are a changing: Respiratory Therapists as part of the multidisciplinary, community, primary health care team. Can J Respir Ther. 2018. https://doi.org/10.29390/cjrt-2018-024.

Johnson B, Abraham M, Shelton TL. Patient- and family-centered care: partnerships for quality and safety. NC Med. 2009;70(2):125–30.

Clark CM. Health literacy: The current state of practice among respiratory therapists. Doctoral dissertation. University of North Carolina at Charlotte, USA. 2009. https://www.proquest.com/docview/305094995?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. Accessed 06 Oct 2022.

Taggart J, Williams A, Dennis S, et al. A systematic review of interventions in primary care to improve health literacy for chronic disease behavioral risk factors. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-13-49.

World Health Organization. About social determinants of health [Internet]. Geneva: WHO. www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/. Accessed 06 Oct 2022.

Burrowes K, Kumar H, Clark A, et al. Bridging the gap between respiratory research and health literacy: an interactive web-based platform. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2021;7:163–6.

Apter AJ, Bryant-Stephens T, Morales KH, et al. Using IT to improve access, communication, and asthma in African American and Hispanic/Latino Adults: rationale, design, and methods of a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;44:119–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2015.08.001.

McGee JS, Meraz R, Myers DR, Davie MR. Telehealth services for persons with chronic lower respiratory disease and their informal caregivers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pract Innovat. 2020;5(2):165–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000122. (ISSN: 2377-889X).

Contreras CM, Metzger GA, Beane JD, et al. Telemedicine: patient-provider clinical engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:1692–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04623-5.

Jang S, Kim Y, Cho WK. A systematic review and meta-analysis of telemonitoring interventions on severe COPD exacerbations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):6757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136757.

Nimmon L, Poureslami I, FitzGerald JM. Telehealth interventions for management of chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) and asthma: a critical review. IJHISI. 2013;8(1):35–46.

Jeminiwa R, Hohmann L, Qian J, et al. Impact of eHealth on medication adherence among patients with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2019;149:59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2019.02.011.

Steventon A, Ariti C, Fisher E, Bardsley M. Effect of telehealth on hospital utilisation and mortality in routine clinical practice: a matched control cohort study in an early adopter site. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2): e009221. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009221.

Rochester CL, Spruit MA, Holland AE. Pulmonary rehabilitation in 2021. JAMA. 2021;326(10):969–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.6560.

Candemir I, Ergun P, Kaymaz D, et al. Comparison of unsupervised home-based pulmonary rehabilitation versus supervised hospital outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2019;13(12):1195–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2019.1675516.

Hakami R, Gillis D, Poureslami I, Fitzgerald MJ. Patient and professional perspectives on nutrition in chronic respiratory disease self-management: reflections on nutrition and food literacies. Health Lit Res Pract. 2018;2(3):e166–74.

Poureslami I, Rootman I, Doyle-Waters MM, et al. Health literacy, language, and ethnicity-related factors in newcomer asthma patients to Canada: a qualitative study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(2):315–22.

Reeves D, Blickem C, Vassilev I, et al. The contribution of social networks to the health and self-management of patients with long-term conditions: a longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6): e98340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098340.

Aboumatar H, Naqibuddin M, Neiman J, et al. Methodology and baseline characteristics of a randomized controlled trial testing a health care professional and peer-support program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the BREATHE2 study. Contemp ClinTrials. 2020;94: 106023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2020.106023.

Apter AJ, Perez L, Han X, et al. Patient advocates for low-income adults with moderate to severe asthma: a randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(10):3466-3473.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.06.058.

Schafheutle EI, Fegan T, Ashcroft DM. Exploring medicines management by COPD patients and their social networks after hospital discharge. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1019–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0688-7.

Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906289376.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Celine Bergeron, Alizeh Akhtar, Jessica Shum and Sarah Chae for their contributions to the research program mentioned in this review. We would also like to thank the many patients and health care providers who participated in the many focus groups etc., which provided the basis for much of the material presented here.

Funding

Our health literacy research program has been funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) (project fund #20R24515), The funding agency has no roles in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author has made substantial contributions to writing, editing, and preparing the manuscript. IP and JMF conceived the idea for this review article. IP initially drafted the manuscript and JMF, NT, SG, RG, and DL critically revised the manuscript and had the final approval for submission. All authors read and approved of the final submitted version of manuscript and agree to be accountable for their own contributions. The authors agreed to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial and non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Poureslami, I., FitzGerald, J.M., Tregobov, N. et al. Health literacy in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) care: a narrative review and future directions. Respir Res 23, 361 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02290-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02290-5