Abstract

Background

Targeted lung cancer screening is effective in reducing mortality by upwards of twenty percent. However, screening is not universally available and uptake is variable and socially patterned. Understanding screening behaviour is integral to designing a service that serves its population and promotes equitable uptake. We sought to review the literature to identify barriers and facilitators to screening to inform the development of a pilot lung screening study in Scotland.

Methods

We used Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review methodology and PRISMA-ScR framework to identify relevant literature to meet the study aims. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies published between January 2000 and May 2021 were identified and reviewed by two reviewers for inclusion, using a list of search terms developed by the study team and adapted for chosen databases.

Results

Twenty-one articles met the final inclusion criteria. Articles were published between 2003 and 2021 and came from high income countries. Following data extraction and synthesis, findings were organised into four categories: Awareness of lung screening, Enthusiasm for lung screening, Barriers to lung screening, and Facilitators or ways of promoting uptake of lung screening. Awareness of lung screening was low while enthusiasm was high. Barriers to screening included fear of a cancer diagnosis, low perceived risk of lung cancer as well as practical barriers of cost, travel and time off work. Being health conscious, provider endorsement and seeking reassurance were all identified as facilitators of screening participation.

Conclusions

Understanding patient reported barriers and facilitators to lung screening can help inform the implementation of future lung screening pilots and national lung screening programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death and reduced life expectancy worldwide, with lung cancer the primary cause of cancer death [1, 2]. In 2020, there were a reported 2.1 million new lung cancer cases and 1.8 million deaths [3]. Lung cancer incidence and mortality are closely linked to smoking patterns and subsequent tobacco control programmes [4,5,6], and while smoking cessation is related to the highest reduction in mortality, detection at an early stage also offers the prospect of improved survival rates [7].

Historically, lung cancer detection largely arises through symptomatic presentation [8]. However, symptoms are often generic in nature and not considered serious at the time of their onset, with prolonged intervals from both symptom onset to help seeking, and from first help seeking to diagnosis [8,9,10]. Furthermore, lung cancer is predominately asymptomatic in the early stages, taking several years to reach the stage when it is most frequently diagnosed. Thus, advanced local disease and metastatic spread at diagnosis is commonplace, rendering the cancer less likely to be curatively treatable [11].

With the success of breast, cervical and bowel cancer screening, there has been an ongoing interest in establishing an effective equivalent programme for lung cancer [7]. While programmes based on chest X-rays or sputum cytology screening have not shown benefit, early detection via low-dose computed tomography (CT) has been trialled widely through North America and Europe and is now endorsed by the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) [12]. Early trials demonstrated that more cancers, and specifically increased stage I cancers, could be identified by routine low-dose CT screening [13,14,15]. Recent studies have also shown survival benefit—but only when screening is successfully targeted towards at risk populations to minimise ineffective screening and over-diagnosis [7, 16, 17].

Worldwide, lung cancer screening is not consistently offered at a national level, with current provision taking the form of local pilots and programmes in Europe, and screening in the USA is often reliant on physician support for implementation [7]. For screening to achieve improved outcomes, it requires sufficient uptake in target groups; within the trial setting, initial uptake of screening has been notably low, in the range of 50–60% [18,19,20,21], although this is difficult to calculate accurately as not all people offered screening are eligible for LDCT. Moreover, uptake is higher in people who used to smoke and in higher socio-economic status (SES) individuals, and lower in those most at risk (i.e. people who have smoked long term in lower SES groups) [18, 22,23,24]. Patterns of low and socially skewed uptake have also been reported in settings where screening is offered as part of routine healthcare services [25].

This scoping review aimed to identify literature exploring barriers and facilitators to participation in lung screening using low-dose CT. We were particularly interested in identifying barriers related to issues of deprivation and rurality that may affect screening participation. This review forms part of a larger preparatory study including stakeholder consultation, focus groups and document review to inform the development of a pilot low-dose CT lung screening intervention to be tested in the eligible Scottish population (‘LungScot’)[26]. Findings from the review and subsequent pilot will inform the roll out of targeted lung screening in Scotland.

Methods

The review used a scoping methodology with the intention of providing high quality evidence in a short timeframe [27,28,29]. The aims of the review were to identify the barriers and facilitators to participation in lung screening, to identify issues related to deprivation and rurality, and to inform the development of a subsequent pilot lung screening intervention. This chosen methodology facilitates insight to a broad topic area to understand the landscape and map key concepts, rather than focusing on a research question looking at effectiveness—thus better reflecting the aims and purpose of our review [27,28,29]. We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s five-step process including identifying the research question, identifying the studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarising and reporting the results [27]. Reporting of the review follows the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews PRISMA-ScR [30, 31].

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this study was developed as part of the full feasibility study by the LungScot team. It was subject to internal and external peer review during the full study design and funding application and discussed with the wider study advisory group including clinical and government experts in screening. The protocol was not registered or published (See Additional file 1).

Eligibility criteria and dimensions of interest

Research studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published, in English, within the specified timeframe (January 2000-May 2021), in a peer reviewed journal, and reported the results of empirical research in full. This time period was chosen to reflect the growing interest in lung screening and advent of lung screening trials worldwide. We primarily sought studies reporting on barriers and facilitators from high-income countries that examined behavioural aspects of lung screening behaviour. Details of the eligibility criteria are listed in Box 1. Articles focused on non-UK health system specific factors (such as opportunistic physician referrals in the US health system) were excluded unless they also contained data on patient related barriers.

Results

Summary of included studies

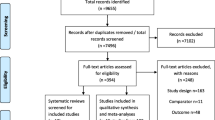

We identified 21 papers for final inclusion in the review after consultation with the wider research team [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. We excluded papers where findings did not address patient barriers and facilitators to low-dose CT lung screening. All papers originated from high income countries including the United States (US) (n = 15), United Kingdom (UK) (n = 5) and Australia (n = 1). There was a mix of qualitative (n = 8), quantitative (n = 10) and mixed methods studies (n = 3) included and articles were published between 2003 and 2020. Seventeen out of the 21 papers were published from 2017 to 2020, reflecting the fast-paced movement of lung cancer screening research in high income countries in recent years. Despite our intended focus on deprivation and rurality, few papers that met the inclusion criteria were found with content on these issues. Articles were a mix of prospective and retrospective studies, and study subjects included people who currently smoke, people who don’t smoke and people who used to smoke. Figure 1 shows the screening and selection process to arrive at this final set of studies.

Table 1 shows the summary characteristics of the included studies.

Evidence synthesis

The data from the included studies have been synthesised into a series of themes and sub-themes to summarise and explain the findings. These have been organised into four superordinate themes: Awareness of lung screening, Enthusiasm for lung screening, Barriers to screening, and Facilitators and ways of promoting screening participation. Table 2 indicates which sub-themes are present in each of the 21 studies.

Awareness of lung screening

The literature consistently demonstrated low awareness of lung screening (e.g. [51, 57]). Participants were aware of other screening programmes but had often not heard of or been previously screened for lung cancer. However, some studies did explore views among people who had been offered lung screening and so lack of awareness was most applicable in studies of wider, screening eligible populations. For example, in a study by Raz et al., 18.9% of their sample had undergone lung screening, while the remainder had not heard of it nor been offered lung screening [49]. US studies in our review suggested that participants did not discuss lung screening with their providers beyond basic conversations about eligibility and intention to refer, and respondents typically suggested that they were not provided with sufficient information about screening before taking part [44]. A lack of provider awareness of lung screening could also impact on the number of opportunities to be offered screening, as has been shown in a US context [57].

There was a wider awareness of other cancer screening services, and many studies (11 out of 21) reported that participants were aware of the importance of early detection and its impact on survival e.g. [39, 41, 44].

Enthusiasm for lung screening

Despite low awareness of lung screening opportunities in the reviewed literature, there was strong support in principle for lung screening, and a broader awareness of the link between early detection and improved survival rates [56]. For example, Lowenstein et al. found in a qualitative study with 42 screening eligible patients that participants were in favour of screening, found it acceptable, and related screening to prevention and early detection [44]. A number of studies also suggested that people sought reassurance or peace of mind from undergoing screening (as discussed in relation to facilitators), although this was complex: some participants reported that this gave them the ‘go ahead’ to continue smoking, while for others it was a motivation to quit [39, 46].

Barriers to lung screening

Barriers to screening participation constituted the largest category in our analysis and a number of sub-themes were identified across the included studies.

Concerns about the test itself

Concerns about aspects of the screening test itself were reported as barriers to participation in ten studies in this review (see Table 2). The main concerns about undergoing screening were related to unnecessary radiation exposure, over-diagnosis and the risk of a false positive result e.g. [43,44,45, 57]. For Lowenstein et al's participants, the concerns centred around the psychological harms of false positives, incidental findings and radiation exposure [44]. However, it is important to note that these barriers were considered to be minimal in relation to the potential benefits of early detection. This was echoed in other included studies: Roth et al. reported less than half of participants raised these concerns and believed the benefits of screening to outweigh the harms in their interviews with a screening eligible population, while Quaife et al. reported only one participant being concerned about radiation exposure in a survey and interview study with 184 participants [46, 50].

Fear of a cancer diagnosis/ cancer worry

Fifteen included studies reported that fear of cancer diagnosis, or cancer worry, mediated lung screening intentions, as shown in Table 2. Related to these is an avoidance of lung cancer information [37]. A number of these studies reported that their participants did not want to know if they had cancer as an avoidance mechanism for the associated worry of waiting for a screening result and the distress of a cancer diagnosis [40, 41, 49]. There was a perception among some study participants that a lung cancer diagnosis was a ‘death sentence’ [44, 46], although not all studies found a clear association between lung cancer worry and intention to be screened [47]. Notably, a survey by See et al. also found that worry about lung cancer was positively associated with lung screening participation, and so it can be a motivator to taking part for some invitees [53].

Fatalism

Evidence of fatalism among screening eligible participants was related to screening participation in a number of studies e.g. [46, 54, 55]. In a mixed methods study of an at-risk population with low socioeconomic status, Quaife et al. found that 20% of their participants felt that they had smoked too long to benefit from lung screening. Further qualitative inquiry elucidated that screening could not get the participants ‘a new pair of lungs’ and they expressed a lack of control over lung cancer, even if they stopped smoking [46].

Fear of invasive procedures

There was evidence in included studies for fear of invasive procedures that may be necessary for the screening test itself [38, 44, 57]. Participants in these studies also reported a fear of follow-up investigations, procedures or treatments associated with a lung cancer diagnosis.

Mistrust of health professionals and services

A number of included studies (7 out of 21) reported a mistrust in health professionals and services, sometimes related to poor experiences in the past or negative associations with loss of loved ones, leading to avoidance of any interactions or engagement with services e.g. [37, 39, 42, 50]. Quaife et al. described the association of hospitals with a ‘slippery slope towards death’, with a desire to avoid them [46]. Conversely, trust in a referring clinician or physician endorsement were positively associated with screening participation [50], although this could be mediated by smoking status [47].

Perceived risk of lung cancer

Perceived risk was reported as a barrier to participation in lung screening (13 of 21 papers) eg [43, 48, 49, 51]. Absence of symptoms of lung cancer and a feeling of being fit and well led to a perception among some study participants that screening is unnecessary e.g. [49, 51].

Smoking-related stigma

Perceived stigma related to current or past smoking behaviour was reported as a barrier to participation. For example, complex feelings of shame, self-blame and stigma were found by Greene et al. in their qualitative study of influences on lung screening decision-making among recent participants [42]. Their participants reported being treated unfairly by health care professionals due to their smoking and a failure to understand the cultural connotations of smoking in previous generations.

Practical barriers

A number of practical barriers were reported in the included studies. These ranged from issues such as time off from work [57], competing priorities in terms of chronic conditions or caring responsibilities [46], and travel and transport [51]. Cost also posed a barrier to screening participation, as some believed they would have to pay for the test or there would be financial implications of travel or taking time off work [49]. In US studies, concerns and misunderstandings about insurance cover were also reported [48, 55].

Facilitators or ways of promoting uptake of lung screening

Being health conscious

A concept that appeared to be common among those who had participated in screening and experienced fewer barriers to doing so was a desire to keep ‘on top of’ their health and a stronger sense of self-efficacy [41, 43, 52]. Roth et al. report that having seen friends or family members go through cancer motivated people to monitor their own health and act quickly, again showing that previous negative experiences can lead to either promoting screening behaviour, or screening avoidance [50]. Jonnalanga et al. found a significant association between intention to screen and self-efficacy and have applied the self-regulation model to their findings to interpret behavioural cues for screening [43, 58].

Provider endorsement

Intention to screen was influenced by provider recommendation or endorsement in a number of included studies [41, 51, 57]. In the USA, the opportunity to be screened is often reliant on physician referral, and many participants in the US studies indicated that they would go for screening if their primary care physician recommended it [43, 45]. Greene et al. suggest that provider recommendation is especially important if patients have a positive and trusting relationship with health care providers [42], while Quaife et al. highlight patient preferences for GP endorsement and health professional support to answer questions and address concerns about screening in a UK context [46, 47].

Motivation for behavioural change and smoking cessation

Participating in lung screening was associated with providing motivation to quit smoking among participants in a small number of the studies in the review [39, 42, 46, 57]. Participants described being given a ‘clean slate’ by a negative lung screen as providing the motivation to quit smoking [42, 46].

Seeking reassurance

Further motivation to attend lung screening came in the form of people wanting to ‘see the state of their lungs’ in order to assess whether action was needed (lifestyle change or quitting smoking). Receiving a clear scan was regarded as giving peace of mind that they were not going to develop lung cancer and reassured study participants that they did not have to worry [42].

Discussion

Summary

This is the first review to provide a concise summary of the key patient barriers and facilitators to lung screening, comparing the literature and drawing together the evidence. This review includes 21 papers reporting patient perceptions of barriers and facilitators to targeted lung cancer screening using low-dose CT. Although it identified a heterogeneous group of papers with different populations, designs and methodologies, there was strong consistency in the findings, allowing for the aggregation of findings and synthesis into a number of reported themes. While awareness of lung cancer screening is low, support for lung screening and awareness of the benefits of early detection was evident across the included studies. However, the manner in which intention to screen translates to participation in screening is mediated by a number of barriers to action. Psychological barriers to lung screening were commonly reported in the literature and included fear of a cancer diagnosis, fear of invasive procedures, mistrust of health professionals and services, fatalism, perceived stigma, and low perceived risk of lung cancer. Facilitators to lung screening identified in the literature were high perception of risk of lung cancer, being ‘health conscious’, provider recommendation or endorsement, seeking reassurance and motivation for behaviour change i.e. smoking cessation.

Comparison with wider literature and theory

Low levels of awareness of lung screening in the literature was noted. The relative infancy of lung screening, the low levels of opportunistic lung screening in the USA, and the lack of a national UK programme for lung screening could account for the low level of awareness compared with other forms of screening. Across the wider literature on screening, support for screening is a very common finding [59,60,61]. However, being in favour of screening is not the single biggest predictor of screening behaviour, as a number of cognitive, behavioural, environmental and system factors converge to influence performed screening behaviours in the gap between intention and behaviour [62].

A number of participants reported concerns about features of the screening test such as radiation exposure and false positives. Comparisons can be drawn with breast screening where women were concerned about the accuracy of the test [63], whereas test-related concerns about bowel screening related more to competency in carrying out the test and disgust handling faeces [59]. While it is important to address lung screening test-related concerns and provide information and opportunity to discuss these where relevant, practical barriers were far outweighed by perceived benefits in the reviewed literature. However, if we consider participation as a set of scales, these concerns could be enough to tip someone into non-participation in combination with other issues.

Fear of a cancer diagnosis was one of the most dominant themes in the literature, coupled with fear of invasive procedures—suggesting that psychological harms associated with cancer worry and waiting for screening results prove significant barriers to screening participation. This mirrors the literature in relation to other screening programmes and decisions to seek help for cancer symptoms, which can help us predict behaviours in relation to lung screening participation [59, 64]. Fatalism was also proposed as a cognitive response to non-participation in screening. Fatalism is a complex response that is likely bound with fear and avoidance and could be something that is entrenched in social discourses of cancer in deprived populations [65, 66].

Related to fear is a mistrust of health professionals and services and perceived stigma or judgement for smoking, which are powerful psychological emotions that can mediate engagement with health services, lead to avoidance, and that are socially patterned [67]. There is a call to understand this more in the Scottish context, and we have conducted some [68] focus group work to gain insight to this and other barriers to lung screening. Two of the authors have conducted some co-design work identifying similar barriers to lung screening using blood biomarkers [69]. Building trust in health systems is therefore key to improving accessibility of services [70] and breaking down some of the perceived conditions on ‘offers’ of health care (and therefore resistance to these offers), as outlined in Dixon-Woods et al. candidacy framework [34].

Perceived risk of lung cancer can also mediate participation in screening depending on a person’s concern that they may be at risk of lung cancer, with risk influenced by factors such as smoking status and symptom recognition and appraisal. Moreover, even among those groups who perceived their risk of lung cancer to be high, factors such as mistrust or fear of diagnosis may still prevent them from taking part. There is also scope for further work to understand the complexities of smoking status and its impact on lung screening decisions, to develop the work of Quaife et al. [46, 47].

Applying psychological theory is helpful here to understand the influence of psychological barriers—such as perceptions of risk, complex fears, and stigma—on screening behaviour. Leventhal’s self-regulation model purports that self-assessed risk and cues to action are underpinned by representations of cancer and the self, linking with other evident themes in the review around cancer worry and narratives of a ‘cancer death sentence’ [58]. However, these cues, or motivations, are only one component of understanding health behaviour as Michie’s behaviour change wheel (encompassing motivation, capability and opportunity) shows, acknowledging both internal and external influences on health behaviours such as screening to be considered when designing an intervention [71].

There was a consistent theme in included studies about the practical barriers to screening participation such as cost, time and travel. Weighing up the significance of practical barriers relative to psychological and behavioural factors is an important consideration in pilot studies of lung screening. See et al. suggest that practical barriers are minor or not ‘deal breakers’ in terms of preventing people from participating in screening, but this was a study conducted among those who participated [53]. Gaining insight to real world scenarios among non-participants is needed for balance in understanding the influence of practical barriers. Issues of access are also likely to be significant for the rural population of Scotland with areas of high deprivation, and work is underway elsewhere in the UK that can provide insight to addressing these issues (e.g. the use of mobile units) in combination with more in-depth, qualitative work [72].

There was less evidence in the review for facilitators to screening but some themes were identified that could influence taking part or help promote screening. Being ‘health conscious’ was identified as positively influencing screening participation and was related to self-regulation and self-efficacy in one study [43]. Wardle et al. encapsulate this issue in their discussion of being health conscious and its links to opportunity, material hardship, adverse experiences, and the resources to think about future health; this has been built into subsequent models of health and screening behaviour [62, 73]. Together with issues of fear and trust, opportunities to be ‘health conscious’ are embedded in wider social structures that go beyond screening to a more upstream public health approach to addressing social inequalities.

Provider recommendation and endorsement were also identified as facilitators to lung screening, which has also been an important factor in promoting bowel screening [59, 74]. This will rely on promoting provider awareness of and support for lung screening. It is unclear, however, how endorsement will translate into action in the context of a lung screening programme [46], and as the discussion of trust highlights, the importance of this relationship should not be undervalued.

Another facilitator to take part in lung screening, to confirm that cancer is not present and to give the individual peace of mind, is seeking reassurance—this has been identified as a motivation for taking part in other screening programmes [75, 76]. However, there is a need to understand the impact of reassurance on future symptom appraisal, help-seeking and repeat screening behaviour [77, 78].

Offers of lung screening can also prompt positive action in relation to other areas of health promotion and lifestyle change, most notably smoking cessation. There is emerging evidence that lung screening can be a motivator to quit smoking and positively impacts smoking cessation rates [79]. Integrated smoking cessation has also been identified as a key component of a lung screening programme to ensure cost effectiveness and long-term health gains [7, 80].

Strengths and limitations

Our review provides a novel synthesis and insights to evidence from a behavioural science perspective examining how barriers to screening participation may combine in real world situations to explain the gap between screening intentions and screening behaviour.

The review is limited to patient reported barriers and facilitators published and indexed in seven databases over a recent twenty year period, and does not include papers published since mid-2021 or wider implementation issues impacting on lung screening provision. Lung screening is a very fast paced area of current research and so more up to date evidence becomes ever available and may shift the evidence base. Smoking status could impact on the views expressed, e.g. among a group of people attending a smoking cessation class [49], and this variation in position should be considered when interpreting findings.

Conclusions

Lung cancer screening has been shown to reduce lung cancer mortality through early detection. However, overall uptake of lung screening (where available) has been relatively low and is socially patterned. This review of the literature has provided insight into patient reported barriers and facilitators to participation in lung cancer screening; this provides the opportunity to combine with empirical work to inform future implementation strategies of lung screening pilots, trials, and to help shape future national lung screening programmes.

Availability of data and materials

Extracted information and synthesised data is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- LDCT:

-

Low dose computer tomography

- CT:

-

Computer tomography

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- USPSTF:

-

United States Preventative Services Task Force

- US:

-

United States (of America)

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, Soerjomataram I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127(16):3029–30.

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Am Cancer Soc. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. The global cancer observatory: cancer today. 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Prentice R, Lopez AD, et al. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):351–64.

Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Baade PD. The International Epidemiology of Lung Cancer: geographical distribution and secular trends. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(8):819–31.

Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(8):1893–907.

Oudkerk M, Liu S, Heuvelmans MA, Walter JE, Field JK. Lung cancer LDCT screening and mortality reduction—evidence, pitfalls and future perspectives. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(3):135–51.

Barrett J, Hamilton W. Pathways to the diagnosis of lung cancer in the UK: a cohort study. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9(1):31.

Corner J, Hopkinson J, Fitzsimmons D, Barclay S, Muers M. Is late diagnosis of lung cancer inevitable? Interview study of patients’ recollections of symptoms before diagnosis. Thorax. 2005;60(4):314–9.

Birt L, Hall N, Emery J, Banks J, Mills K, Johnson M, et al. Responding to symptoms suggestive of lung cancer: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2014;1(1): e000067.

Hamilton W, Peters TJ, Round A, Sharp D. What are the clinical features of lung cancer before the diagnosis is made? A population based case-control study. Thorax. 2005;60(12):1059–65.

Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, Azzoli CG, Berry DA, Brawley OW, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307(22):2418–29.

Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, Naidich DP, McGuinness G, Miettinen OS, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet (London, England). 1999;354(9173):99–105.

Diederich S, Wormanns D, Semik M, Thomas M, Lenzen H, Roos N, et al. Screening for early lung cancer with low-dose spiral CT: prevalence in 817 asymptomatic smokers. Radiology. 2002;222(3):773–81.

Pastorino U, Bellomi M, Landoni C, De Fiori E, Arnaldi P, Picchio M, et al. Early lung-cancer detection with spiral CT and positron emission tomography in heavy smokers: 2-year results. The Lancet. 2003;362(9384):593–7.

Walter JE, Heuvelmans MA, Bock GHD, Yousaf-Khan U, Groen HJM, Aalst CMVD, et al. Characteristics of new solid nodules detected in incidence screening rounds of low-dose CT lung cancer screening: the NELSON study. Thorax. 2018;73(8):741–7.

Ostrowski M, Marjański T. Low-dose computed tomography screening reduces lung cancer mortality. Adv Med Sci. 2018;63:230–6.

Quaife SL, Ruparel M, Dickson JL, Beeken RJ, McEwen A, Baldwin DR, et al. Lung Screen uptake trial (LSUT): randomized controlled clinical trial testing targeted invitation materials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):965–75.

Marcus PM, Lenz S, Sammons D, Black W, Garg K. Recruitment methods employed in the National Lung Screening Trial. J Med Screen. 2012;19(2):94–102.

McRonald FE, Yadegarfar G, Baldwin DR, Devaraj A, Brain KE, Eisen T, et al. The UK Lung Screen (UKLS): demographic profile of first 88,897 approaches provides recommendations for population screening. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014;7(3):362–71.

Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409.

Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Clapp JD, Clingan KL, The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team Writing committee, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the randomized national lung screening trial. JNCI. 2010;102(23):1771–9.

Hestbech MS, Siersma V, Dirksen A, Pedersen JH, Brodersen J. Participation bias in a randomised trial of screening for lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011;73(3):325–31.

Yousaf-Khan U, Horeweg N, van der Aalst C, Ten Haaf K, Oudkerk M, de Koning H. Baseline characteristics and mortality outcomes of control group participants and eligible non-responders in the NELSON lung cancer screening study. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(5):747–53.

Zahnd WE, Eberth JM. Lung cancer screening utilization: a behavioral risk factor surveillance system analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(2):250–5.

Edinburgh Imaging. LUNGSCOT: University of Edinburgh; 2022. https://www.ed.ac.uk/clinical-sciences/edinburgh-imaging/research/themes-and-topics/body-systems/lungs-respiratory/lung-cancer/lungscot. Accessed 25 May 2022.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation science : IS. 2010;5:69.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13:224.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:59.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):35.

Cavers D, Cunningham-Burley S, Watson E, Banks E, Campbell C. Experience of living with cancer and comorbid illness: protocol for a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5): e013383.

Cavers D, Habets L, Cunningham-Burley S, Watson E, Banks E, Campbell C. Living with and beyond cancer with comorbid illness: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(1):148–59.

Ali N, Lifford KJ, Carter B, McRonald F, Yadegarfar G, Baldwin DR, et al. Barriers to uptake among high-risk individuals declining participation in lung cancer screening: a mixed methods analysis of the UK Lung Cancer Screening (UKLS) trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7): e008254.

Carter-Harris L, Brandzel S, Wernli KJ, Roth JA, Buist DSM. A qualitative study exploring why individuals opt out of lung cancer screening. Fam Pract. 2017;34(2):239–44.

Carter-Harris L, Ceppa DP, Hanna N, Rawl SM. Lung cancer screening: what do long-term smokers know and believe? Health Expect. 2017;20(1):59–68.

Delmerico J, Hyland A, Celestino P, Reid M, Cummings KM. Patient willingness and barriers to receiving a CT scan for lung cancer screening. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(3):307–9.

Draucker CB, Rawl SM, Vode E, Carter-Harris L. Understanding the decision to screen for lung cancer or not: a qualitative analysis. Health Expect. 2019;22(6):1314–21.

Greene PA, Sayre G, Heffner JL, Klein DE, Krebs P, Au DH, et al. Challenges to educating smokers about lung cancer screening: a qualitative study of decision making experiences in primary care. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(6):1142–9.

Jonnalagadda S, Bergamo C, Lin JJ, Lurslurchachai L, Diefenbach M, Smith C, et al. Beliefs and attitudes about lung cancer screening among smokers. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(3):526–31.

Lowenstein M, Vijayaraghavan M, Burke NJ, Karliner L, Wang S, Peters M, et al. Real-world lung cancer screening decision-making: barriers and facilitators. Lung Cancer. 2019;133:32–7.

Percac-Lima S, Ashburner JM, Atlas SJ, Rigotti NA, Flores EJ, Kuchukhidze S, et al. Barriers to and interest in lung cancer screening among Latino and Non-Latino current and former smokers. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(6):1313–24.

Quaife SL, Marlow LAV, McEwen A, Janes SM, Wardle J. Attitudes towards lung cancer screening in socioeconomically deprived and heavy smoking communities: informing screening communication. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):563–73.

Quaife SL, Vrinten C, Ruparel M, Janes SM, Beeken RJ, Waller J, et al. Smokers’ interest in a lung cancer screening programme: a national survey in England. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1–10.

Raju S, Khawaja A, Han X, Wang X, Mazzone PJ. Lung cancer screening: characteristics of nonparticipants and potential screening barriers. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020;21(5):e329–36.

Raz DJ, Wu G, Nelson RA, Sun V, Wu S, Alem A, et al. Perceptions and utilization of lung cancer screening among smokers enrolled in a tobacco cessation program. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(1):e115–22.

Roth JA, Carter-Harris L, Brandzel S, Buist DSM, Wernli KJ. A qualitative study exploring patient motivations for screening for lung cancer. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2018;13(7): e0196758.

Schiffelbein JE, Carluzzo KL, Hasson RM, Alford-Teaster JA, Imset I, Onega T. Barriers, facilitators, and suggested interventions for lung cancer screening among a rural screening-eligible population. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720930544.

Schnoll RA, Bradley P, Miller SM, Unger M, Babb J, Cornfeld M. Psychological issues related to the use of spiral CT for lung cancer early detection. Lung Cancer. 2003;39(3):315–25.

See K, Manser R, Park ER, Steinfort D, King B, Piccolo F, et al. The impact of perceived risk, screening eligibility and worry on preference for lung cancer screening: a cross-sectional survey. ERJ Open Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00158-2019.

Smits SE, McCutchan GM, Hanson JA, Brain KE. Attitudes towards lung cancer screening in a population sample. Health Expect. 2018;21(6):1150–8.

Stephens SE, Foley KL, Miller D, Bellinger CR. The effects of health disparities on perceptions about lung cancer screening (LCS): survey results of a patient sample. Lung. 2019;197(6):735–40.

Tonge JE, Atack M, Crosbie PA, Barber PV, Booton R, Colligan D. “To know or not to know…?” Push and pull in ever smokers lung screening uptake decision-making intentions. Health Expect. 2019;22(2):162–72.

Simmons VN, Gray JE, Schabath MB, Wilson LE, Quinn GP. High-risk community and primary care providers knowledge about and barriers to low-dose computed topography lung cancer screening. Lung Cancer. 2017;106:42–9.

Leventhal H, Kelly K, Leventhal EA. Population risk, actual risk, perceived risk, and cancer control: a discussion. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1999;25:81–5.

Cavers D, Calanzani N, Orbell S, Vojt G, Steele RJC, Brownlee L, et al. Development of an evidence-based brief ‘talking’ intervention for non-responders to bowel screening for use in primary care: stakeholder interviews. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):105.

Hersch J, Jansen J, Barratt A, Irwig L, Houssami N, Howard K, et al. Women’s views on overdiagnosis in breast cancer screening: a qualitative study. BMJ. 2013;346: f158.

Henriksen MJV, Guassora AD, Brodersen J. Preconceptions influence women’s perceptions of information on breast cancer screening: a qualitative study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):404.

von Wagner C, Good A, Whitaker KL, Wardle J. Psychosocial determinants of socioeconomic inequalities in cancer screening participation: a conceptual framework. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33:135–47.

Feldstein AC, Perrin N, Rosales AG, Schneider J, Rix MM, Glasgow RE. Patient barriers to mammography identified during a reminder program. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(3):421–8.

Reynolds LM, Bissett IP, Consedine NS. Emotional predictors of bowel screening: the avoidance-promoting role of fear, embarrassment, and disgust. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):518.

Beeken RJ, Simon AE, von Wagner C, Whitaker KL, Wardle J. Cancer fatalism: deterring early presentation and increasing social inequalities? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(10):2127–31.

Miles A, Rainbow S, von Wagner C. Cancer fatalism and poor self-rated health mediate the association between socioeconomic status and uptake of colorectal cancer screening in England. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(10):2132–40.

Davis JL, Bynum SA, Katz RV, Buchanan K, Green BL. Sociodemographic differences in fears and mistrust contributing to unwillingness to participate in cancer screenings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(4 Suppl):67–76.

Cavers D, Nelson M, Rostron J, et al. Optimizing the implementation of lung cancer screening in Scotland: focus group participant perspectives in the LUNGSCOT study. Health Expect. 2022;25(6):3246–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13632.

Brown LR, Sullivan F, Treweek S, et al. Increasing uptake to a lung cancer screening programme: building with communities through co-design. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:815. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12998-0.

Doblytė S. The vicious cycle of distrust: access, quality, and efficiency within a post-communist mental health system. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292: 114573.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42.

Bartlett EC, Kemp SV, Ridge CA, et al. Baseline results of the West London lung cancer screening pilot study - Impact of mobile scanners and dual risk model utilisation. Lung Cancer. 2020;148:12–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.07.027.

Wardle J, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(6):440–3.

Kaushal A, Hirst Y, Tookey S, Kerrison RS, Marshall S, Prentice A, et al. Use of a GP-endorsed non-participant reminder letter to promote uptake of bowel scope screening: A randomised controlled trial in a hard-to-reach population. Prev Med. 2020;141: 106268.

Hope KA, Moss E, Redman CWE, Sherman SM. Psycho-social influences upon older women’s decision to attend cervical screening: a review of current evidence. Prev Med. 2017;101:60–6.

Cantor SB, Volk RJ, Cass AR, Gilani J, Spann SJ. Psychological benefits of prostate cancer screening: the role of reassurance. Health Expect. 2002;5(2):104–13.

Renzi C, Whitaker KL, Wardle J. Over-reassurance and undersupport after a ‘false alarm’: a systematic review of the impact on subsequent cancer symptom attribution and help seeking. BMJ Open. 2015;5(2): e007002.

Barnett KN, Weller D, Smith S, Orbell S, Vedsted P, Steele RJC, et al. Understanding of a negative bowel screening result and potential impact on future symptom appraisal and help-seeking behaviour: a focus group study. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):584–92.

Brain K, Carter B, Lifford KJ, Burke O, Devaraj A, Baldwin DR, et al. Impact of low-dose CT screening on smoking cessation among high-risk participants in the UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial. Lung Cancer. 2017;72(10):912–8.

Steliga MA, Yang P. Integration of smoking cessation and lung cancer screening. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(Suppl 1):S88-s94.

Shelton RC, Lee M. Sustaining evidence-based interventions and policies: recent innovations and future directions in implementation science. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S2):S132–4.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to members of our patient advisory group who commented on the design of the scoping review and with whom we shared the synthesis.

Funding

The LUNGSCOT study is funded by the Chief Scientists Office of the Scottish Government, reference HIPS/19/52.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DC designed and conducted the scoping review, and drafted and prepared the manuscript for publication. MN designed the scoping review, completed data searching and screening of included studies and helped refine the manuscript. JR assisted with data extraction and synthesis of included studies and helped refine the manuscript. CC conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. KAR conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. AA conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. MM conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. EJRVB conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. FS conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. LRB contributed to article selection, commented on scoping review analysis and helped refine the manuscript. RJS conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. GD conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. ARN conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, commented on the design of the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. DW conceived of the LUNGSCOT study, designed the scoping review, commented on the analysis and helped refine the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This review was exempt from National Health Service (NHS) and internal University of Edinburgh Medical School Research Ethics Committee (EMREC) ethical review because no primary data were collected.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Frank Sullivan declares that the Universities of Dundee and St. Andrew’s received funding from Oncimmune for the Early Detection of Cancer of the Lung Scotland (ECLS) trial from 2013 to 2021.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Study protocol.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cavers, D., Nelson, M., Rostron, J. et al. Understanding patient barriers and facilitators to uptake of lung screening using low dose computed tomography: a mixed methods scoping review of the current literature. Respir Res 23, 374 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02255-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02255-8