Abstract

Background

Observational studies have reported controversial results on the association between obesity and head and neck cancer risk. This study aimed to perform a two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to assess the causal association between obesity and head and neck cancer risk using publicly available genome-wide association studies (GWAS) summary statistics.

Methods

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for obesity [body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), whole body fat mass, lean body mass, and trunk fat mass] and head and neck cancer (total head and neck cancer, oral cavity cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, and oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer) were retrieved from published GWASs and used as genetic instrumental variables. Five methods including inverse-variance-weighted (IVW), weighted-median, MR–Egger, weighted mode, and MR-PRESSO were used to obtain reliable results, and odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. Tests for horizontal pleiotropy, heterogeneity, and sensitivity were performed separately.

Results

Genetically predicted BMI was negatively associated with the risk of total head and neck cancer, which was significant in the IVW [OR (95%CI), 0.990 (0.984–0.996), P = 0.0005], weighted-median [OR (95%CI), 0.984 (0.975–0.993), P = 0.0009], and MR-PRESSO [OR (95%CI), 0.990 (0.984–0.995), P = 0.0004] analyses, but suggestive significant in the MR-Egger [OR (95%CI), 0.9980 (0.9968–0.9991), P < 0.001] and weighted mode [OR (95%CI), 0.9980 (0.9968–0.9991), P < 0.001] analyses. Similar, genetically predicted BMI adjust for smoking may also be negatively associated with the risk of total head and neck cancer (P < 0.05). Genetically predicted BMI may be negatively related to the risk of oral cavity cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, and oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer (P < 0.05), but no causal association was observed for BMI adjust for smoking (P > 0.05). In addition, no causal associations were observed for other exposures and outcomes (all P > 0.05).

Conclusion

This MR analysis supported the causal association of BMI-related obesity with decreased risk of total head and neck cancer. However, the effect estimates from the MR analysis were close to 1, suggesting a slight protective effect of BMI-related obesity on head and neck cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Head and neck cancer is an umbrella term for a range of cancers including oral cavity, pharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, laryngeal, sinus, and salivary gland cancers [1]. In 2020, head and neck cancer were one of the most common cancers worldwide (1.43 million new cases and 0.51 million deaths), accounting for 7.4% of all cancers (19.3 million new cases) and 5.1% of all cancer deaths worldwide (10.0 million deaths) [2]. The prognosis and survival of head and neck cancer depend on tumor stage, site of involvement, and human papillomavirus (HPV) status [3]. Smoking and alcohol consumption, as well as high-risk types of HPV, are widely recognized as major risk factors for head and neck cancer [1]. Identifying potential factors associated with head and neck cancer plays an important role in disease prevention and prognosis management.

Obesity is associated with the development and progression of many cancers and is considered the second most common and modifiable cause of cancer development after smoking [4, 5]. Recently, several observational studies have reported an association between obesity and head and neck cancer risk [6,7,8]. Khanna et al. showed that being overweight and obese were significantly associated with a reduced risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [6]. Chen et al. found that obesity was negatively associated with the risk of head and neck cancer [7]. Gaudet et al. reported that obesity was not associated with the incidence of head and neck cancer [8]. However, a meta-analysis demonstrated a positive association between BMI and head and neck cancer risk in non-smokers [9]. Inconsistent results among these observational studies may be influenced by confounding factors and reverse causality. Mendelian randomization (MR) studies, based on genetic epidemiology, have been widely used to explore the causal relationship between exposure and outcome [10, 11]. In contrast to traditional observational studies, MR studies use genetic variants associated with exposure to assess possible causality with outcomes and can reduce potential biases from confounding and reverse causality [12, 13].

This study aimed to assess the causal association between obesity exposure and head and neck cancer using genetic variants associated with obesity as non-confounding instruments.

Methods

Study design and data source

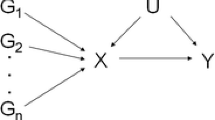

This study used two-sample MR to assess the relationship between obesity and head and neck cancer risk. All data used are publicly available and can be searched through the genome-wide association study (GWAS) Catalog (available at: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/) and the MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) database (available at: https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/). Three assumptions were established include: (1) genetic variants were associated with the exposure (relevance); (2) genetic variates share no unmeasured cause with the outcome (independence); (3) genetic variants do not affect outcome except through their potential effect on the exposure (exclusion restriction) (Fig. 1). The requirement of ethical approval for this was waived by the Institutional Review Board of National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, because the data was accessed from GWAS database (a publicly available database). The need for written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College due to retrospective nature of the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

The Mendelian randomization study aims and assumptions. Assumption 1: genetic variants were associated with the exposure (relevance); assumption 2: genetic variates share no unmeasured cause with the outcome (independence); assumption 3: genetic variants do not affect outcome except through their potential effect on the exposure (exclusion restriction)

Instrumental variable selection

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with exposure (obesity) and outcome (head and neck cancer) were summarized in Table 1. The variables included in exposure were body mass index (BMI), BMI adjusted for smoking, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), WHR adjusted for BMI, WHR adjusted for BMI in non-smoker, WHR adjusted for BMI and smoking, whole body fat mass, lean body mass, and trunk fat mass. Instrumental variables for BMI were based on a meta-analysis of GWAS of 97 BMI-associated loci in 339,224 Europeans [14]. Instrumental variables for BMI adjusted for smoking, WHR adjusted for BMI in non-smoker, and WHR adjusted for BMI and smoking were obtained from a meta-analysis of GWAS on obesity in 241,258 Europeans [15]. Instrumental variables for WHR and WHR adjusted for BMI were derived from a meta-analysis of GWAS of 49 WHR-associated loci in 224,459 Europeans [16]. Instrumental variables for lean body mass were based on a meta-analysis of GWAS in 8,327 Europeans [17]. Instrumental variables for whole body fat mass and trunk fat mass were derived from the UK Biobank and obtained from the MRC IEU database. The variables included in the outcome were total head and neck cancer, oral cavity cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, and oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer. Instrumental variables for total head and neck cancer, oral cavity cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, and oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer were derived from the UK Biobank and obtained from the MRC IEU database. Specifically, 373,122 Europeans were included when total head and neck cancer was the outcome, including 1,106 head and neck cancer patients; 372,373 Europeans were included when oral cavity cancer was the outcome, including 357 oral cavity cancer patients; 372,510 Europeans were included when oropharyngeal cancer was the outcome, including 494 oropharyngeal cancer patients; and 372,855 Europeans were included when oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer was the outcome, including 839 oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer patients. For the selection of instrumental variables, a series of quality control steps were used to select eligible instrumental SNPs. First, SNPs with genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10− 8) associated with exposure were selected. Second, the selected SNPs are not in linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2 < 0.001, genetic distance = 10,000 kb). Third, the selected SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01 were deleted. The F statistic and variance explained (R2) is also an indicator to assess the strength of the relationship between SNPs and exposure. If the F statistic of the SNPs-exposure association is > 10, the likelihood of weak instrumental variable bias is small [18].

Pleiotropy

Pleiotropy is the association of a genetic variant with multiple risk factors on different causal pathways. Horizontal pleiotropy of genes would violate assumption 2 and assumption 3 of the three assumptions of MR, and MR analysis should be performed on the premise of ensuring no horizontal pleiotropy. SNPs associated with confounders were excluded (assumption 2). SNPs directly related to the outcome without affecting outcome through exposure were excluded (assumption 3). MR-Egger Intercept test was used to test for horizontal pleiotropy, and the P-value for the intercept > 0.05 indicates no horizontal pleiotropic effects. MR-Egger is a weighted linear regression method based on the Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (InSIDE) assumption which can give valid tests and consistent estimates of causal effects even if all instrumental variables are invalid [19].

Statistical analysis

Two-sample MR analysis was performed using the “TwoSampleMR” package in R software. Exposure-SNP and outcome-SNP were harmonized using the “harmonise_data” function of the TwoSampleMR package so that variant effect estimates corresponded to the same allele. For each SNP in each exposure, individual MR effect estimates were calculated using the Wald method (SNP-exposure beta/SNP-outcome beta). Five methods including fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted (IVW), MR-Egger, weighted-median, weighted mode, and MR-PRESSO methods were used to analyze the association between obesity and head and neck cancer risk. The IVW method uses a meta-analysis approach to combine the Wald estimates for each SNP to obtain an overall estimate of the effect of obesity on head and neck cancer risk [20], which was the primary analysis used to generate causal effect estimates in the current study. The weighted-median method provides a robust and consistent estimate of the effect, even if nearly 50% of genetic variants were invalid instruments [21]. When most of the instrumental variables with similar causal estimates are valid, the weighted model method remains plausible even if some of the instrumental variables do not meet the requirements of the MR for causal inference [22]. The MR-PRESSO method detects horizontal pleiotropy and corrects for horizontal pleiotropy by removing outliers, as well as determining whether there is a substantial change in causal effects before and after removal of outliers [23]. However, the MR-PRESSO outlier test requires at least 50% of the genetic variation to be a valid tool and relies on the InSIDE assumption. Cochran’s Q test was utilized to evaluate the statistical heterogeneity among SNPs in the IVW method, and P < 0.05 was considered significant heterogeneity. The leave-one-out analyses were used to assess the reliance of an MR analysis on a particular SNP, and the symmetry directly observed in the plot indicates null pleiotropy. Furthermore, the bidirectional MR analysis was conducted to determine if there was a reverse causal association between exposure and outcome. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to evaluate the results of the MR analysis. For exposure BMI and BMI adjust after smoking, the OR values showed results for each increase of 5-units. P-value < 0.00139 = 0.05/36 (9 exposures and 4 outcomes) was considered statistically significant, whereas P-value between 0.00139 and 0.05 was considered suggestive significance in the IVW, weighted-median, MR-Egger, weighted mode, and MR-PRESSO analyses. All statistical analyses were performed by R software, version 4.1.1.

Results

Selection of instrument variables

Table 2 reports the number of SNPs and the results of SNP tests that were ultimately included in the analysis. After screening, 78 SNPs associated with BMI and 28 SNPs associated with WHR were retained when head and neck cancer was the outcome. There were 75 BMI-related SNPs and 29 WHR-related SNPs retained when oral cavity cancer was the outcome. There were 78 SNPs related to BMI and 28 SNPs related to WHR retained when oropharyngeal cancer was the outcome. There were 69 BMI-related SNPs and 27 WHR-related SNPs retained when oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer was the outcome. The MR-Egger analysis showed no horizontal pleiotropy for all retained SNPs (all P > 0.05). The F statistics associated with each SNP-exposure was much greater than 10, indicating that the possibility of weak instrumental variable bias was small. Furthermore, the results of the heterogeneity test showed that the selected SNPs were not heterogeneous (all P > 0.05).

Two-sample MR analysis for causal association of obesity with head and neck cancer

Table 3 shows the causal association between obesity and head and neck cancer risk. The results demonstrated that genetically predicted BMI was negatively associated with the risk of total head and neck cancer, which was significant in the IVW [OR (95%CI), 0.990 (0.984–0.996), P = 0.0005], weighted-median [OR (95%CI), 0.984 (0.975–0.993), P = 0.0009], and MR-PRESSO [OR (95%CI), 0.990 (0.984–0.995), P = 0.0004] analyses, but suggestive significant in the MR Egger [OR (95%CI), 0.9980 (0.9968–0.9991), P < 0.001] and weighted mode [OR (95%CI), 0.9980 (0.9968–0.9991), P < 0.001] analyses. For oral cavity cancer, genetically predicted BMI may be negatively related to the risk of oral cavity cancer, which was suggestive significant in the weighted-median [OR (95%CI), 0.992 (0.987–0.997), P = 0.0033], weighted mode [OR (95%CI), 0.991 (0.983–0.998), P = 0.0154], and MR-PRESSO [OR (95%CI), 0.997 (0.994-1.000), P = 0.0347] analyses. For oropharyngeal cancer, genetically predicted BMI may be negatively related to the risk of oropharyngeal cancer, which was suggestive significant in the IVW [OR (95%CI), 0.996 (0.992–0.999), P = 0.0287] and MR-PRESSO [OR (95%CI), 0.996 (0.992–0.999), P = 0.0228] analyses. For oral and oropharyngeal cancer, genetically predicted BMI may be negatively related to the risk of oral and oropharyngeal cancer, which was suggestive significant in the IVW [OR (95%CI), 0.993 (0.988–0.998), P = 0.0037], weighted-median [OR (95%CI), 0.991 (0.982–0.999), P = 0.0325], weighted mode [OR (95%CI), 0.988 (0.978–0.999), P = 0.0302], and MR-PRESSO [OR (95%CI), 0.993 (0.988–0.997), P = 0.003] analyses.

For exposure BMI adjust for smoking, genetically predicted BMI adjust for smoking may be negatively associated with the risk of head and neck cancer, which was suggestive significant in the IVW [OR (95%CI), 0.988 (0.978–0.999), P = 0.0314], MR Egger [OR (95%CI), 0.980 (0.962–0.999), P = 0.016], weighted-median [OR (95%CI), 0.983 (0.969–0.998), P = 0.0215], weighted mode [OR (95%CI), 0.981 (0.967–0.995), P = 0.0158], and MR-PRESSO [OR (95%CI), 0.988 (0.978–0.999), P = 0.0445] analyses. However, no causal associations were observed between BMI adjust for smoking and oral cavity cancer and oropharyngeal cancer and oral and oropharyngeal cancer (all P > 0.05). For exposure WHR, genetically predicted WHR may be negatively related to the risk of head and neck cancer, which was suggestive significant in the IVW [OR (95%CI), 0.998 (0.996-1.000), P = 0.0337] and MR-PRESSO [OR (95%CI), 0.998 (0.996-1.000), P = 0.0313] analyses. In addition, no causal associations between other exposures and head and neck cancer risk were observed (all P > 0.05). Figure 2 presents the forest plots of the causal link between obesity and head and neck cancer risk.

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the relationship between obesity and head and neck cancer was not caused by any individual SNP (Fig. 3). Moreover, the bidirectional MR analysis showed that there was not a reverse causal association between BMI-related obesity and head and neck cancer [IVW: β (95%CI), 0.521 (-1.692, 2.734), P = 0.645; MR-Egger: β (95%CI), -0.633 (-5.873, 4.607), P = 0.820; weighted-median method: β (95%CI), 1.064 (-1.935, 4.064), P = 0.487].

Discussion

This study used summary statistics from published GWAS for a two-sample MR analysis to explore the causal association between obesity and head and neck cancer risk. The results demonstrated that genetically predicted BMI-related obesity was negatively associated with the risk of total head and neck cancer, while no causal association was found between WHR-related obesity and total head and neck cancer risk.

Several published observational studies have reported inconsistent results regarding obesity and head and neck cancer [7,8,9]. Two cohort studies have reported that no statistically significant association was observed between obesity and head and neck cancer incidence [8, 24]. However, some studies have shown that a high BMI is associated with a lower risk of head and neck cancer [7, 25, 26]. Etemadi et al. reported that the risk of head and neck cancer was negatively associated with BMI among current smokers [26]. A meta-analysis of cohort studies showed that WHR was positively associated with the risk of head and neck cancer regardless of smoking, while a positive association with BMI was found only among never smokers [9]. To address the controversy between these results, this study used MR analysis to investigate the causal association between obesity and head and neck cancer risk. Our results found that BMI-related obesity was negatively associated with the risk of total head and neck cancer, and this association may be persisted after adjusting for smoking. However, a recent MR study by Gormley et al. showed no causal association between BMI and oral and oropharyngeal cancer risk [27]. Our results demonstrated that BMI may be negatively related to the risk of oropharyngeal cancer, but no causal association was found between BMI adjust for smoking and the risk of oropharyngeal cancer. It may be that smoking is an important confounder influencing the risk of head and neck cancer, as postulated by Gormley et al. However, both BMI and BMI adjust for smoking were causally associated with total head and neck cancer risk, suggesting that there may be a causal association between BMI and the risk of a particular type of head and neck cancer. In addition, the OR value of our MR analysis results was close to 1, which suggested that although there was a causal association between obesity and total head and neck cancer risk, obesity may not play a major role in the development of head and neck cancer. For specific types of head and neck cancer, the MR study by Fussey et al. found that there was not a causal association between obesity and benign nodular thyroid disease or thyroid cancer [28]. Since head and neck cancer includes the oral cavity, pharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, laryngeal, sinus and salivary gland cancers, the causal association between obesity and a particular type of head and neck cancer needs to be explored in subsequent studies.

The mechanism by which obesity reduces the risk of head and neck cancer remains unclear. A systematic review summarized the potential mechanisms between obesity and head and neck cancer [25]. Many substances associated with obesity such as fatty acid synthase, fatty acid binding protein, phospholipase A2, and adipokines may be involved in the development of head and neck cancer [25]. Adipokines are hormones secreted by adipose tissue that can regulate inflammatory and metabolic processes and influence cell growth and proliferation [29]. Adipokines associate obesity with low-grade chronic inflammation [30]. This low-grade chronic inflammation contributes to the formation of a tumor microenvironment that affects cell plasticity through epithelial-mesenchymal transition, dedifferentiation, immune cell polarization, reactive oxygen species, and cytokines [31, 32]. The association between dysregulation of adipokine and adipokine receptor expression and head and neck cancer has been demonstrated [33]. Pathways involved in these processes include Janus kinase/signal sensor and transcriptional activator (JAK/STAT pathway), Phosphatidylinositol kinase (PI3/Akt/mTOR), and Peroxisome proliferator activator receptor (PPAR) [33]. Leptin and adiponectin are the most studied adipokines. Obese people have higher levels of leptin than people of normal weight [34]. A decrease in circulating leptin levels can be detected in patients with cancer, including oral squamous cell carcinoma [35]. Decreased adiponectin levels were observed in the course of obesity and adipose tissue malnutrition [36]. Moreover, other potential factors such as HPV may also influence the association between obesity and head and neck cancer. Tan et al. found a negative association between obesity and the risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in HPV seronegative cases, but not in HPV seropositive cases [37].

This study first investigated the causal association between obesity and head and neck cancer risk. This study may provide genetic evidence for the controversial results between obesity and head and neck cancer risk. However, several limitations of this study should be considered. First, although our study found the causal association between BMI-related obesity and head and neck cancer risk, we were unable to identified the specific type of head and neck cancer due to data limitations. Second, the study population included in the MR analysis was of European descent, and whether the results are representative of the entire population remains to be verified. Third, there should not be overlapping participants for exposure and outcome in a two-sample MR study, while the extent of sample overlap in the present study is unknown. However, the use of a strong instrument (e.g., F statistic > 10) in this study minimizes the potential bias of sample overlap.

Conclusions

This two-sample MR study found that genetically predicted BMI-related obesity was negatively associated with the risk of total head and neck cancer. These findings provide new evidence for the etiology of head and neck cancer, although obesity may not be a major factor. Future studies could focus on the causal link between obesity and different types of head and neck cancer.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the GWAS Catalog, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/.

Abbreviations

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- IEU:

-

Integrative Epidemiology Unit

- SNPs:

-

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip ratio

- InSIDE:

-

Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect

- IVW:

-

Inverse-variance weighted

References

Mody MD, Rocco JW, Yom SS, Haddad RI, Saba NF. Head and neck cancer. Lancet (London England). 2021;398:2289–99.

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49.

Cohen N, Fedewa S, Chen AY. Epidemiology and demographics of the Head and Neck Cancer Population. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am. 2018;30:381–95.

Ma J, Huang M, Wang L, Ye W, Tong Y, Wang H. Obesity and risk of thyroid cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis of 21 observational studies. Med Sci monitor: Int Med J experimental Clin Res. 2015;21:283–91.

Avgerinos KI, Spyrou N, Mantzoros CS, Dalamaga M. Obesity and cancer risk: emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metab Clin Exp. 2019;92:121–35.

Khanna A, Sturgis EM, Dahlstrom KR, Xu L, Wei Q, Li G, et al. Association of pretreatment body mass index with risk of head and neck cancer: a large single-center study. Am J cancer Res. 2021;11:2343–50.

Chen Y, Lee YA, Li S, Li Q, Chen CJ, Hsu WL, et al. Body mass index and the risk of head and neck cancer in the chinese population. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;60:208–15.

Gaudet MM, Patel AV, Sun J, Hildebrand JS, McCullough ML, Chen AY et al. Prospective studies of body mass index with head and neck cancer incidence and mortality. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2012; 21: 497–503.

Gaudet MM, Kitahara CM, Newton CC, Bernstein L, Reynolds P, Weiderpass E, et al. Anthropometry and head and neck cancer:a pooled analysis of cohort data. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:673–81.

Larsson SC, Burgess S. Causal role of high body mass index in multiple chronic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mendelian randomization studies. BMC Med. 2021;19:320.

Fang Z, Song M, Lee DH, Giovannucci EL. The role of mendelian randomization studies in deciphering the effect of obesity on Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:361–71.

Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1–22.

Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G. Reading mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2018;362:k601.

Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518:197–206.

Justice AE, Winkler TW, Feitosa MF, Graff M, Fisher VA, Young K, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of 241,258 adults accounting for smoking behaviour identifies novel loci for obesity traits. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14977.

Shungin D, Winkler TW, Croteau-Chonka DC, Ferreira T, Locke AE, Mägi R, et al. New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015;518:187–96.

Medina-Gomez C, Kemp JP, Dimou NL, Kreiner E, Chesi A, Zemel BS, et al. Bivariate genome-wide association meta-analysis of pediatric musculoskeletal traits reveals pleiotropic effects at the SREBF1/TOM1L2 locus. Nat Commun. 2017;8:121.

Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27:1133–63.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–25.

Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–65.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some Invalid Instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–14.

Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1985–98.

Verbanck M, Chen C-Y, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–8.

Hashibe M, Hunt J, Wei M, Buys S, Gren L, Lee YC. Tobacco, alcohol, body mass index, physical activity, and the risk of head and neck cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian (PLCO) cohort. Head Neck. 2013;35:914–22.

Wang K, Yu XH, Tang YJ, Tang YL, Liang XH. Obesity: an emerging driver of head and neck cancer. Life Sci. 2019;233:116687.

Etemadi A, O’Doherty MG, Freedman ND, Hollenbeck AR, Dawsey SM, Abnet CC. A prospective cohort study of body size and risk of head and neck cancers in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2014; 23: 2422–9.

Gormley M, Dudding T, Thomas SJ, Tyrrell J, Ness AR, Pring M, et al. Evaluating the effect of metabolic traits on oral and oropharyngeal cancer risk using mendelian randomization. Elife. 2023;12:e82674.

Fussey JM, Beaumont RN, Wood AR, Vaidya B, Smith J, Tyrrell J. Does obesity cause thyroid Cancer? A mendelian randomization study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:e2398–407.

Unamuno X, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Rodríguez A, Becerril S, Frühbeck G, Catalán V. Adipokine dysregulation and adipose tissue inflammation in human obesity. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48:e12997.

Daas SI, Rizeq BR, Nasrallah GK. Adipose tissue dysfunction in cancer cachexia. J Cell Physiol. 2018;234:13–22.

Ritter B, Greten FR. Modulating inflammation for cancer therapy. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1234–43.

Varga J, Greten FR. Cell plasticity in epithelial homeostasis and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:1133–41.

Tzanavari T, Tasoulas J, Vakaki C, Mihailidou C, Tsourouflis G, Theocharis S. The role of Adipokines in the establishment and progression of Head and Neck Neoplasms. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:4726–48.

Myers MG Jr, Leibel RL, Seeley RJ, Schwartz MW. Obesity and leptin resistance: distinguishing cause from effect. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:643–51.

Gharote HP, Mody RN. Estimation of serum leptin in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of oral pathology & medicine: official publication of the International Association of oral pathologists and the American Academy of oral Pathology. 2010; 39: 69–73.

Parida S, Siddharth S, Sharma D. Adiponectin, obesity, and Cancer: clash of the Bigwigs in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20.

Tan X, Nelson HH, Langevin SM, McClean M, Marsit CJ, Waterboer T, et al. Obesity and head and neck cancer risk and survival by human papillomavirus serology. Cancer causes & control: CCC. 2015;26:111–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Beijing Hope Run Special Fund of Cancer Foundation of China (No. LC2022A30) and the Major Project of Medical Oncology Key Foundation of Cancer Hospital Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (No. CICAMS-MOMP2022010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LG and XH designed the study. LG wrote the manuscript. LT, JY, and JP collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. LG critically reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The requirement of ethical approval for this was waived by the Institutional Review Board of National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, because the data was accessed from GWAS database (a publicly available database). The need for written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College due to retrospective nature of the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gui, L., He, X., Tang, L. et al. Obesity and head and neck cancer risk: a mendelian randomization study. BMC Med Genomics 16, 200 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-023-01634-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-023-01634-4