Abstract

Background

Feeding dogs with diets rich in protein may favor putrefactive fermentations in the hindgut, negatively affecting the animal’s intestinal environment. Conversely, prebiotics may improve the activity of health-promoting bacteria and prevent bacterial proteolysis in the colon. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of dietary supplementation with fructooligosaccharides (FOS) on fecal microbiota and apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) in dogs fed kibbles differing in protein content. Twelve healthy adult dogs were used in a 4 × 4 replicated Latin Square design to determine the effects of four diets: 1) Low protein diet (LP, crude protein (CP) 229 g/kg dry matter (DM)); 2) High protein diet (HP, CP 304 g/kg DM); 3) Diet 1 + 1.5 g of FOS/kg; 4) Diet 2 + 1.5 g of FOS/kg. The diets contained silica at 5 g/kg as a digestion marker. Differences in protein content were obtained using different amounts of a highly digestible swine greaves meal. Each feeding period lasted 28 d, with a 12 d wash-out in between periods. Fecal samples were collected from dogs at 0, 21 and 28 d of each feeding period. Feces excreted during the last five days of each feeding period were collected and pooled in order to evaluate ATTD.

Results

Higher fecal ammonia concentrations were observed both when dogs received the HP diets (p < 0.001) and the supplementation with FOS (p < 0.05). The diets containing FOS resulted in greater ATTD of DM, Ca, Mg, Na, Zn, and Fe (p < 0.05) while HP diets were characterized by lower crude ash ATTD (p < 0.05). Significant interactions were observed between FOS and protein concentration in regards to fecal pH (p < 0.05), propionic acid (p < 0.05), acetic to propionic acid and acetic + n-butyric to propionic acid ratios (p < 0.01), bifidobacteria (p < 0.05) and ATTD of CP (p < 0.05) and Mn (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

A relatively moderate increase of dietary protein resulted in higher concentrations of ammonia in canine feces. Fructooligosaccharides displayed beneficial counteracting effects (such as increased bifidobacteria) when supplemented in HP diets, compared to those observed in LP diets and, in general, improved the ATTD of several minerals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The bacterial populations that inhabit the intestinal tract play a role of great importance in animal health, as they are involved in nutritional, functional and immunological processes [1]. Several studies have shown that the symbiotic relationship between intestinal microbiota and their host may be positively modulated through dietary strategies that include supplementation with prebiotics and variation of the amount, type and balance of dietary nutrients [2]. Among nutrients, protein represents a key factor in dog nutrition and may have a significant influence on the intestinal microbial fermentations by supporting proteolysis [3]. In particular, even though dogs are a carnivorous species, high amounts of dietary protein have demonstrated to favor a high synthesis of undesirable putrefactive metabolites, such as ammonia and volatile branched-chain fatty acids (BCFA) in the canine hindgut [4, 5].

Several publications have recently highlighted interesting evidence on the use of prebiotic substances both in humans [6] and other species, including companion animals such as dogs [7, 8]. In particular, fructooligosaccharides (FOS) have displayed beneficial effects on the composition [9, 10] and metabolism of canine intestinal microbiota, by favoring a shift from putrefactive to saccharolytic fermentations [11, 12].

Nowadays, the development of nutritional strategies aimed at positively influencing the intestinal health of companion animals is important, with recent trends in canine nutrition focusing on diets rich in proteins (the so-called “ancestral diets”) based on the philosophy of feeding dogs foods similar to those eaten by their wild ancestors [13]. Our hypothesis is that higher dietary protein concentrations may induce an intensification of intestinal putrefactive fermentations and that FOS may counteract this effect. As such, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of a dietary supplementation with FOS on fecal bacterial populations, fecal fermentative end-products concentrations and apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) in dogs fed diets with different protein content.

Methods

The study was carried out according to the Italian legislation implementing the European Council Directive 2010/63 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of the University of Bologna. Informed consent was obtained from all dog owners prior to the beginning of the study.

Animals and diets

Twelve healthy adult dogs (household dogs, different breeds and living in different environments; mean age ± SD = 3.6 ± 1.6) were used. The average body weight ± SD of the dogs was 19.5 ± 6.2 kg. During the study they kept living in their usual environment. Each dog was regularly vaccinated and periodically treated for intestinal parasites; dogs had exhibited no clinical signs of gastrointestinal disorders during the previous 12 months.

Four dry, extruded and complete diets formulated for adult dogs (Effeffe Pet Food S.p.A., Italy), based on cereals, meat and meat by-products, oils and fat, protein plant extract, minerals and yeasts, were used: 1) Low protein diet (LP, crude protein (CP) 229 g/kg dry matter (DM)); 2) High protein diet (HP, CP 304 g/kg DM); 3) LP + FOS; 4) HP + FOS. The sole source of animal protein in the diets was a swine greaves meal (CP 685 g/kg DM; in vitro DM and CP digestibility 0.71 and 0.86, respectively). Fructooligosaccharides (Beneo OPS, FOS from partially hydrolyzed inulin from chicory with a degree of polymerization between 2 and 8; Beneo GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) were incorporated in diets 3 and 4 before extrusion, at a final concentration of 15 g/kg. The experimental diets did not contain significant amounts of soluble fiber sources other than the FOS added to diets 3 and 4. Silica was included in all diets at the dose of 5 g/kg as a source of acid-insoluble ash to be used as a digestion marker. The amount of greaves meal and the presence or not of FOS in the formulation represented the only remarkable difference between the four experimental diets.

In vitro digestibility of the swine greaves meal included in the experimental diets was performed following the method based on the 2-step procedure (2 h incubation with HCl, pepsin and gastric lipase followed by 4 h with pancreatin and bile salts) described by Biagi et al. [14]. Dry ground samples of the swine greaves meal were digested in triplicate. The chemical composition of the experimental diets and the swine greaves meal is shown in Table 1.

Experimental design and samples collection

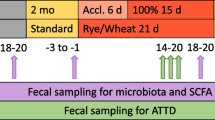

Dogs received four dietary treatments according to a 4 × 4 Latin square experimental design. Each feeding period lasted 28 days, with 12 days wash-out periods in between. During the wash-out periods all dogs were fed the LP diet, as it represented the basal diet during the study. Over the whole crossover study, each dog received all experimental diets, following the same sequence (LP → HP → LP + FOS → HP + FOS) but starting from a different diet.

Dogs were fed twice a day; the daily food amount for each dog was calculated on the basis of the energy content of the experimental diets (calculated using the modified Atwater conversion factors) and the animals’ daily energy requirements, according to the recommendations for the maintenance of small and medium sized adult dogs: 132 kcal/kg BW0.75 [15].

On days 0, 21 and 28 of each feeding period a fresh fecal sample was collected from each dog within 30 min from defecation and thereafter frozen at − 80 °C for chemical and microbiological analyses. From days 24 to 28 of each feeding period, feces excreted from dogs were pooled and stored at − 20 °C for nutrients analyses and ATTD assessment.

Chemical analyses and ATTD calculation

Determination of nutrients in diets, swine greaves meal and fecal samples was performed according to AOAC International standard methods [16] (method 950.46 for water, method 954.01 for CP, method 920.39 for ether extract, method 920.40 for starch, method 942.05 for crude ash). Fiber fractions were determined according to the procedure described by Van Soest et al. [17], where neutral detergent fiber (NDF) was assayed with a heat stable amylase, and acid detergent fiber (ADF) was expressed inclusive of residual ash. Acid-insoluble ash was determined according to Vogtmann et al. [18]. For the determination of minerals, samples of diets and feces were previously diluted with a nitric acid solution (15 M) and processed through microwave mineralization, according to the method US EPA 3052 [19]. The analysis was carried out by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES Optima 2100; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Quantification of macrominerals was performed with the torch in radial position by using a Meinhard nebulizer coupled with a cyclonic spray chamber, while trace elements were assessed with the torch in axial position with the utilization of an ultrasonic wave nebulizer (CETAC U5000; Teledyne Cetac Technologies, Omaha, NE, USA), according to the method US EPA 6010c [20].

Apparent total tract digestibility of DM was calculated using the following equation:

100 − [(100 × % marker in the diet)/ % marker in feces]

Apparent total tract digestibility of each nutrient was calculated using the following equation:

100 − [%nutrient in feces × (100 − % DM digestibility)/ % nutrient in the diet]

Fecal pH was measured using a SevenMulti pH meter (Mettler Toledo, Milan, Italy) on diluted fecal samples (1:10 in distilled water). Ammonia was measured using a commercial kit (Urea/BUN – Color; BioSystems S.A., Barcelona, Spain). Volatile fatty acids (VFA) were analyzed according to Biagi et al. [21]. For the determination of biogenic amines, samples were diluted 1:5 with perchloric acid (0.3 M); biogenic amines were later separated by HPLC and quantified through fluorimetry, according to the method proposed by Stefanelli et al. [22].

Microbial analyses

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted and isolated from fecal samples (~ 200 mg) using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini-Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Isolated DNA concentration and purity were measured using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Template DNA was diluted to 50 ng/μl and stored at − 20 °C until further analysis. Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) was performed using specific primers for total bacteria, Escherichia coli, Bifidobacterium genus, Lactobacillus genus, Enterococcus genus, and Clostridium perfringens (Table 2).

Samples were analysed in duplicate in FrameStar® 96 Well Skirted ninety-six-well reaction plates capped with qPCR Adhesive Clear Plate Seal (4titude Limited, Surrey, UK). The qPCR assay was performed using a MasterCycler ep realPlex4 (Eppendorf, Wesseling-Berzdorf, Germany). Amplification was performed in duplicate for each bacterial group within each sample. For amplification, 15 μl final volume containing 7.5 μl 2X SensiFAST No-ROX PCR Master Mix (Bioline GmbH, Luckenwalde, Germany), 4.8 μl of nuclease-free water, 0.6 μl of each 10 pmol primer and 1.5 μl of template DNA were used. The amplification cycle was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, at 95 °C for 5 s, primer annealing at 55–61 °C for 10 s and at 72 °C for 8 s. The cycle was repeated 40 times. Cycle threshold values were plotted against standard curves for quantification of the target bacterial DNA from fecal samples. To generate standard curves, 10-fold serial dilutions of purified and quantified PCR products were used. The standard curves of the individual qPCR assays were obtained by PCR using specific primers (Table 2) and DNA extracted from the fecal samples. Individual reactions of the standard curves were run in duplicate on each plate for the respective bacterial group. Melting curves were checked after amplification to ensure single product amplification of consistent melting temperature. Results were reported as log10 16S ribosomal DNA gene copies/g fresh matter.

Statistical analysis

First, for each tested parameter except digestibility data, results obtained after 21 and 28 d of each treatment were compared by one-way ANOVA. Since significant differences were not observed for any of the measured parameters, it was decided to use the mean values obtained from each dog at 21 and 28 d for statistical data analysis.

In the present study a 2 × 2 factorial arrangement of treatments (two different protein concentrations and the presence or absence of FOS in the diet) was used. Data were analyzed by the General Linear Model procedure. The model included dietary protein concentration, FOS and their respective interaction as fixed effects and the dog and period as random effects. Results from samples collected at the beginning (Day 0) of each feeding period were not included in the analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. All the statistical computations were performed with Statistica 10.0 (Stat Soft Italia, Padua, Italy).

Results

All the animals remained in good health throughout the study (experimental design provided for a duration of 160 days).

The interaction between protein concentration and FOS influenced fecal pH (p < 0.05). Supplementation with FOS resulted in lower pH in feces of dogs receiving the HP diet and, conversely, increased this parameter when dogs were fed with the LP diet (Table 3). Fecal concentrations of ammonia were affected by both dietary protein concentration (41.1 vs. 58.6 μmol/g of feces for LP and HP, respectively; p < 0.001) and FOS (53.1 vs. 46.6 μmol/g of feces for diets with or without FOS, respectively; p < 0.05) (Table 3). Fecal moisture and concentrations of biogenic amines and total VFA were not affected by treatments (Table 3). A significant interaction between protein concentration and FOS was observed in regards to fecal concentration of propionic acid (p < 0.05), acetic to propionic acid ratio (p < 0.01) and acetic + n-butyric to propionic acid ratio (p < 0.01). In particular, FOS decreased propionic acid when dogs were fed with the LP diet and increased it when dogs were fed with the HP diet. Accordingly, in the presence of FOS, the acetic to propionic acid ratio (p < 0.01) and the acetic + n-butyric to propionic acid ratio were increased in the LP diet and reduced in the HP diet (Table 3).

Most of the bacterial populations evaluated were not modified by any dietary treatment, with the only exception of bifidobacteria for which a significant interaction between protein concentration and FOS was observed (p < 0.01). In particular, FOS reduced these bacteria in feces when dogs were fed with the LP diet and, conversely, they increased them with the HP diet (Table 4).

Supplementation with FOS significantly improved ATTD of DM (0.89 and 0.85 for diets with or without FOS, respectively; p < 0.05), Ca (0.25 and 0.02 for diets with or without FOS, respectively; p < 0.05), Mg (0.20 and 0.01 for diets with or without FOS, respectively; p < 0.05), Na (0.98 and 0.96 for diets with or without FOS, respectively; p < 0.05), Zn (0.34 and 0.19 for diets with or without FOS, respectively; p < 0.05) and Fe (0.15 and 0.01 for diets with or without FOS, respectively; p < 0.05) (Table 5). High protein diets resulted in lower ATTD of crude ash (0.52 and 0.46 for LP and HP, respectively; p < 0.05) (Table 5). Furthermore, a significant interaction between protein concentration and FOS was observed in regards to CP and Mn ATTD (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively). In particular, FOS improved the ATTD of both nutrients in the LP diet and decreased it in the HP diet (Table 5). Apparent total tract digestibility of ether extract, P, K, Cu and starch was not influenced by treatments (average ATTD coefficient of starch was 0.99; data not shown).

Discussion

During the present study, the effects of a moderate FOS supplementation (15 g/kg) on fecal bacterial populations and activity and ATTD were investigated in diets differing in protein content.

Fecal water content was not influenced by dietary treatments and none of the dogs involved in the study showed any gastrointestinal disturbances (such as diarrhea or flatulence). Among the dietary factors causing greater moisture in feces (and negatively influencing fecal quality), there are both the increase of proteolytic fermentations in the hindgut [23] and dietary supplementation with non-digestible oligosaccharides (NDO) [12]. Protein digestion and absorption are considered efficient biological processes in the dog [24]. However, the intake of diets containing large amounts of proteins, even if high digestible, may exceed the digestive/absorptive capacity of the gastrointestinal tract [25]. Consequently, this may lead to a significant increase of proteins reaching the hindgut available for proteolytic fermentations [4, 26], which are known to favor higher osmotic pressure and, consequently, greater water emission into the intestinal lumen [23]. Nevertheless, an increase of fecal water content and negative effects on fecal quality (up to the appearance of diarrhea, in some cases) have been described in dogs receiving diets containing higher protein content compared to that of the HP diets used in the present study (CP 382 and 392 g/kg DM [27]; 655 g/kg DM [28]). It could be presumed that, in the present trial, the HP diets did not affect fecal moisture because of their relatively moderate (and highly digestible) protein content (around 310 g/kg DM).

Moreover, the moderate dose of FOS used in the present study (15 g/kg) might justify the lack of impact on this parameter. In fact, although the physical water-holding properties of NDO and the osmotic action of molecules such as VFA produced by their fermentation are well known [29], several authors, in accordance with the present results, did not report any detrimental effect on fecal moisture (or fecal quality) in dogs when short-chain fructans were supplemented at concentrations lower than 30 g/kg of diet [11, 26, 30].

Interestingly, protein concentration showed a statistically significant, although modest, influence on fecal ammonia, which was increased by HP diets. Ammonia is produced by proteolytic bacteria and represents a toxic and potentially carcinogenic compound that, when present at relevant concentrations in the intestinal lumen, has demonstrated the ability to damage the mucosa [31]. In our study, the increase of fecal ammonia in dogs when fed HP diets induces us to hypothesize increased proteolytic fermentations in the hindgut, as previously suggested [4, 26]. Nevertheless, the fecal concentration of other markers of intestinal bacterial proteolysis (such as BCFAs and biogenic amines) did not increase during HP dietary treatments.

The present results are partially in accordance with recent similar studies in canine species. In a previous similar investigation, the authors described higher fecal ammonia in dogs fed with diets characterized by increasing CP content (from 296 to 485 and 535 g/kg of DM [26]. In a previously cited study, higher ammonia levels (together with higher fecal BCFA concentrations) were observed in feces of dogs fed with a diet containing high amounts of protein (CP from 214 to 655 g/kg of DM) [28]. Similarly, in another study evaluating diets differing in protein content, the authors observed an increase of ammonia and BCFA concentrations when dogs received diets containing higher concentrations of protein (CP from 214 to 392 g/kg of DM) [5].

As described in omnivores such as humans [32] and swines [33], in dogs and cats there is evidence that an increase in dietary protein content increases proteolytic bacteria and reduces microbial populations (in particular, bifidobacteria and lactobacilli) [34, 35] that have been recognized to be beneficial also in these carnivorous species [36]. These outcomes are supported by the well-known “antagonistic pattern” concerning proteolytic bacteria such as clostridia and saccharolytic bacteria such as lactobacilli and bifidobacteria [34]. However, in the present study, protein concentration did not have any effect on the fecal bacterial populations evaluated, partially in accordance with a previously cited study [5]. Conversely, in a previous in vitro trial with canine fecal inoculum, high-protein diets were associated with lower presence of lactobacilli and enterococci [37]. It is possible that in the present study the difference in protein content between LP and HP diets was not large enough to clearly influence fecal microbial populations other than bifidobacteria.

Volatile fatty acids represent the most important fermentative end-products largely produced by bacterial saccharolytic fermentations of non-digestible carbohydrates (such as NDO) [32] and are considered to be beneficial for the host mainly because of their trophic effects on intestinal mucosal cells [38]. For this reason, an increase in VFA production represents a positive outcome often observed during prebiotics (such as FOS) supplementation, also in canine species [7]. Conversely, FOS (as main effect) failed to exert any positive “prebiotic” outcome on fecal parameters evaluated in the present study. On the contrary, FOS diets increased ammonia concentration in the dogs’ feces. In the previously cited in vitro study with canine fecal inoculum, FOS supplemented in the same LP and HP diets used in the present study (but different in protein digestibility) at the same concentration (15 g/kg), decreased pH values and ammonia and increased VFA levels [37]. However, results from in vivo studies investigating the effects of fructans in dogs are contradictory. In this regard it is well known that ammonia and VFA deriving from microbial metabolism are rapidly absorbed along the intestinal tract and that feces may not reflect their actual concentration in the colon [32, 39].

While these mechanisms could explain the lack of effect of FOS supplementation on fecal VFA observed in the present study, the increasing effect on fecal ammonia is more difficult to explain. According to the present results, other authors reported higher ammonia (as well as iso-valerate and total biogenic amines) fecal levels in dogs receiving fructans at doses between 3 and 9 g/kg [12]. Moreover, an increase of fecal concentration of several proteolytic compounds, including ammonia, BCFA and some biogenic amines has been observed during a study with adult cats receiving a diet supplemented with 40 g of FOS/kg [40]. As suggested by the authors of this latter study, the increase of fecal ammonia observed after a dietary supplementation with FOS may be attributable to a shift of nitrogen excretion from urine to feces, as previously described in other investigations in both dogs [41] and cats [42]. In studies evaluating the effects of FOS in pigs’ diets, a complete FOS fermentation prior to the terminal ileum has been documented [43]. This could favor higher bacterial replication in the small intestine. The absence of carbohydrates and the presence of undigested protein available as a source of energy in the hindgut could have favored increased proteolytic activity by a larger number of bacteria [44]. In canine species, there is a paucity of in vivo studies evaluating the effects of FOS on microbial composition and activity in the ileal digesta (given the obvious ethical limits recently imposed by legislation). A study by Swanson et al. with ileally cannulated dogs reported increased concentration of lactobacilli in ileal digesta (and feces) of dogs fed with diets supplemented with FOS and MOS, supporting the hypothesis that prebiotics are able to exert microbial changes even in the upper intestinal tract [45]. In vitro conditions FOS have shown to be readily fermentable also by canine microbiota [46]. Thus, the higher fecal ammonia observed in present study could be also justified by a potential saccharolytic activity favored by FOS in the small intestine or in the proximal colon that was not maintained throughout the large intestine, due to the depletion of the relatively modest dose of the prebiotic ingested. The greater amount of bacteria reaching the hindgut, associated with the unavailability of carbohydrates, might have led to more intensive putrefactive fermentations [44], as demonstrated by the previously cited investigations in swine species [43].

The significant protein concentration x FOS interactions observed in the present study express a different outcome on some fecal parameters (fecal pH, propionic acid, VFA ratios and bifidobacteria) when dogs consumed FOS supplemented diets in relation to their protein content. In particular, FOS exerted typical prebiotic effects when added to HP diets (as they favored lower fecal pH, higher bifidobacteria and propionic acid concentration and, consequently, lower VFA ratios) and, unexpectedly, they acted in the opposite way in LP diets. Based on the previously described hypotheses concerning the potential early fermentation of FOS before the distal colon, the consequent greater bacterial growth eventually stimulated by this substrate might have favored more intensive proteolytic activity in the hindgut that could justify the effects described for LP diets (higher fecal pH, lower propionic concentration and reduced bifidobacteria). In regards to HP diets outcomes, we can only speculate on the possible influence of FOS and higher amount of proteins along the canine intestinal tract on the potential interactions between microbiota and their metabolites [47] that seem to have partially counteracted the effect observed in LP diets. In this regard, also the decreasing effect of FOS on protein ATTD when dogs were fed with HP diets might represent an expression of the previously described and difficult to explain prebiotic effect. Prebiotics can increase the amount of fecal nitrogen of microbial origin by stimulating microbial growth in the hindgut of dogs [48], with a decreasing effect on protein ATTD [26, 49]. In the present study, FOS exerted this effect only in HP diets presumably because of the higher undigested proteins reaching the hindgut where greater proteolysis might have occurred, with consequent higher fecal nitrogen losses.

The slight improvement of ATTD of DM in diets supplemented with FOS observed in the present study can be presumably attributable to the greater bioavailability of some minerals. In this regard, ATTD coefficients of some minerals (in particular, Ca and Mg) in the diets that were not supplemented with FOS were surprisingly low. During the present study, dogs continued to live with their owners and, for that reason, they drank waters characterized by a potentially different mineral content. Nevertheless, the present investigation was based on a crossover experimental design and so a potential “water effect” on ATTD of minerals was presumably avoided.

Results from the present study seem to confirm that NDO and, in particular, inulin-type fructans like FOS, may improve the intestinal absorption of several macro- and trace minerals, as already observed in previous studies in dogs [8]. Among the mechanisms proposed to explain this effect, the acidification of the intestinal chyme (consequent to an increase in VFA production) may represent the more plausible condition favoring higher solubility and bioavailability of minerals [50]. Previously, some authors reported improved crude ash ATTD (and Mg and Ca ATTD, in particular) in dogs receiving a diet supplemented with oligofructose at 10 g/kg, with no effect on fecal pH [51]. Similarly, in our study, FOS (as main effect) did not reduce fecal pH. However, as previously mentioned, feces may not reflect the status of the intestinal environment and it could be supposed that the greater mineral bioavailability induced by FOS may be the consequence of a temporary acidification of digesta along the ileal and/or colonic tract [52], where FOS might have exerted their best prebiotic effect, as previously speculated.

Conclusions

Results from the present study show that even a relatively moderate increase of protein in the diet of adult dogs may exert a negative influence on the canine hindgut, as suggested by the increase of fecal ammonia in the dogs when fed with HP diets. Conversely, the supplementation with FOS improved the ATTD of several minerals, suggesting a transitory acidifying effect along the intestinal tract of the dogs. Moreover, this substrate exhibited some opposite outcomes depending on dietary protein content, displaying, in particular, beneficial counteracting effects on a particularly important bacterial population such as bifidobacteria, when added to HP diets.

Certainly, in companion animals more studies are needed to gain a better understanding of dietary effects on gut microbiota and the consequent impact on health.

In fact, at present, the interactions between dogs and cats and their intestinal microbiome are poorly investigated and many assumptions regarding which bacteria are beneficial and which ones may be detrimental derive from human medicine, despite the fact that the optimal composition of the intestinal microbial community may differ between humans and animals with a more carnivorous nature.

Abbreviations

- ADF:

-

Acid detergent fiber

- ATTD:

-

Apparent total tract digestibility

- BCFA:

-

Branched-chain fatty acids

- CP:

-

Crude protein

- DM:

-

Dry matter

- FOS:

-

Fructooligosaccharides

- HP:

-

High protein

- LP:

-

Low protein

- NDF:

-

Neutral detergent fiber

- NDO:

-

Non-digestible oligosaccharides

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

- VFA:

-

Volatile fatty acids

References

Suchodolski JS. Companion animals symposium: microbes and gastrointestinal health of dogs and cats. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:1520–30.

Walsh CJ, Guinane CM, O’Toole PW, Cotter PD. Beneficial modulation of the gut microbiota. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4120–30.

Windey K, De Preter V, Verbeke K. Relevance of protein fermentation to gut health. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2012;56:184–96.

Zentek J. Influence of diet composition on the microbial activity in the gastro-intestinal tract of dogs. I. Effects of varying protein intake on the composition of the ileum chime and the faeces. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 1995;74:43–52.

Nery J, Goudez R, Biourge V, Tournier C, Leray V, Martin L, Thorin C, Nguyen P, Dumon H. Influence of dietary protein content and source on colonic fermentative activity in dogs differing in body size and digestive tolerance. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:2570–80.

Kellow NJ, Coughlan MT, Reid CM. Metabolic benefits of dietary prebiotics in human subjects: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1147–61.

Patra AK. Responses of feeding prebiotics on nutrient digestibility, faecal microbiota composition and short-chain fatty acid concentrations in dogs: a meta-analysis. Animal. 2011;5:1743–50.

Pinna C, Biagi G. The utilization of prebiotics and synbiotics in dogs. Ital J Anim Sci. 2014;13:169–78.

Swanson KS, Grieshop CM, Flickinger EA, Bauer LL, Chow J, Wolf BW, Garleb KA, Fahey GC. Fructooligosaccharides and lactobacillus acidophilus modify gut microbial populations, total tract nutrient digestibilities and fecal protein catabolite concentrations in healthy adult dogs. J Nutr. 2002;132:3721–31.

Middelbos IS, Fastinger ND, Fahey GC. Evaluation of fermentable oligosaccharides in diets fed to dogs in comparison to fiber standards. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:3033–44.

Flickinger EA, Schreijen EMWC, Patil AR, Hussein HS, Grieshop CM, Merchen NR, Fahey GC. Nutrient digestibilities, microbial populations, and protein catabolites as affected by fructan supplementation of dog diets. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:2008–18.

Propst L, Flickinger EA, Bauer LL, Merchen NR, Fahey GC. A dose-response experiment evaluating the effects of oligofructose and inulin on nutrient digestibility, stool quality, and fecal protein catabolites in healthy adult dogs. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:3057–66.

Buff PR, Carter RA, Bauer JE, Kersey JH. Natural pet food: a review of natural diets and their impact on canine and feline physiology. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:3781–91.

Biagi G, Cipollini I, Grandi M, Pinna C, Vecchiato CG, Zaghini G. A new in vitro method to evaluate digestibility of commercial diets for dogs. Ital J Anim Sci. 2016;15:617–25.

National Research Council of the National Academies (NRC). Nutrient requirements of dogs and cats. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2006.

Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official methods of analysis. 17th ed. Gaithersburg: AOAC Int; 2000.

Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3583–97.

Vogtmann HP, Frirter P, Prabuck AL. A new method of determining metabolizability of energy and digestibility of fatty acids in broiler diets. Br Poult Sci. 1975;16:531–4.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Method 3052. Microwave assisted acid digestion of siliceous and organically based matrices. Washington DC: US EPA, Office of Solid Waste; 1996. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/3052.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2017

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Method 6010C. Inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry. Washington DC: US EPA, Office of Solid Waste; 2007. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-07/documents/epa-6010c.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2017

Biagi G, Piva A, Moschini M, Vezzali E, Roth FX. Effect of gluconic acid on piglet growth performance, intestinal microflora, and intestinal wall morphology. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:370–8.

Stefanelli C, Carati D, Rossoni C. Separation of N1- and N8-acetylspermidine isomers by reversed-phase column liquid chromatography after derivatization with dansyl chloride. J Chromatogr. 1986;375:49–55.

Weber MP, Hernot D, Nguyen PG, Biourge VC, Dumon HJ. Effect of size on electrolyte apparent absorption rates and fermentative activity in dogs. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2004;88:356–65.

Hendriks WH, van Baal J, Bosch G. Ileal and faecal protein digestibility measurement in humans and other non-ruminants - a comparative species view. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(Suppl 2):S247–57.

Hussein HS, Sunvold GD. Dietary strategies to decrease dog and cat fecal odor components. In: Reinhart GA, Carey DP, editors. Recent advances in canine and feline nutrition. Iams Nutr. Symp. Proc. Wilmington: Orange Frazer Press; 2000. p. 153–−168.

Hesta M, Janssens GPJ, Millet S, De Wilde R. Prebiotics affect nutrient digestibility but not faecal ammonia in dogs fed increased dietary protein levels. Brit J Nutr. 2003;90:1007–14.

Nery J, Biourge V, Tournier C, Leray V, Martin L, Dumon H, Nguyen P. Influence of dietary protein content and source on fecal quality, electrolyte concentrations, and osmolarity, and digestibility in dogs differing in body size. J Anim Sci. 2010;88:159–69.

Hang I, Heilmann RM, Grützner N, Suchodolski JS, Steiner JM, Atroshi F, Sankari S, Kettunen A, de Vos WM, Zentek J, Spillmann T. Impact of diets with a high content of greavesmeal protein or carbohydrates on faecal characteristics, volatile fatty acids and faecal calprotectin concentrations in healthy dogs. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:201.

Roberfroid M, Slavin J. Nondigestible oligosaccharides. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2000;40:461–80.

Swanson KS, Grieshop CM, Flickinger EA, Bauer LL, Healy HP, Dawson KA, Merchen NR, Fahey GC. Supplemental fructooligosaccharides and mannanoligosaccharides influence immune function, ileal and total tract nutrient digestibilities, microbial populations and concentrations of protein catabolites in the large bowel of dogs. J Nutr. 2002;132:980–9.

Blachier F, Mariotti F, Huneau JF, Tomé D. Effects of amino acid-derived luminal metabolites on the colonic epithelium and physiopathological consequences. Amino Acids. 2007;33:547–62.

Scott KP, Gratz SW, Sheridan PO, Flint HJ, Duncan SH. The influence of diet on the gut microbiota. Pharmacol Res. 2013;69:52–60.

Rist VT, Weiss E, Eklund M, Mosenthin R. Impact of dietary protein on microbiota composition and activity in the gastrointestinal tract of piglets in relation to gut health: a review. Animal. 2013;7:1067–78.

Zentek J, Marquart B, Pietrzak T, Ballevre O, Rochat F. Dietary effects on bifidobacteria and Clostridium perfringens in the canine intestinal tract. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2003;87:397–407.

Lubbs DC, Vester BM, Fastinger ND, Swanson KS. Dietary protein concentration affects intestinal microbiota of adult cats: a study using DGGE and qPCR to evaluate differences in microbial populations in the feline gastrointestinal tract. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2009;93:113–21.

Deng P, Swanson KS. Gut microbiota of humans, dogs and cats: current knowledge and future opportunities and challenges. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(Suppl):S6–17.

Pinna C, Vecchiato CG, Zaghini G, Grandi M, Nannoni E, Stefanelli C, Biagi G. In vitro influence of dietary protein and fructooligosaccharides on metabolism of canine fecal microbiota. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12:53.

Wong JM, de Souza R, Kendall CW, Emam A, Jenkins DJ. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:235–43.

McNeil NI, Cummings JH, James WPT. Short chain fatty acid absorption by the human large intestine. Gut. 1978;19:819–22.

Barry KA, Wojcicki BJ, Middelbos IS, Vester BM, Swanson KS, Fahey GC. Dietary cellulose, fructooligosaccharides, and pectin modify fecal protein catabolites and microbial populations in adult cats. J Anim Sci. 2010;88:2978–87.

Howard MD, Kerley MS, Sunvold GD, Reinhart GA. Source of dietary fiber fed to dogs affects nitrogen and energy metabolism and intestinal microflora populations. Nutr Res. 2000;20:1473–84.

Hesta M, Hoornaer E, Verlinden A, Janssens GPJ. The effect of oligofructose on urea metabolism and faecal odour components in cats. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2005;89:208–14.

Houdijk JGM. Effects of non-digestible oligosaccharides in young pig diets. PhD Diss. Wageningen: Wageningen Univ.; 1998.

Hamer HM, De Preter V, Windey K, Verbeke K. Functional analysis of colonic bacterial metabolism: relevant to health? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;302:G1–9.

Swanson KS, Grieshop CM, Flickinger EA, Healy HP, Dawson KA, Merchen NR, Fahey GC Jr. Effects of supplemental fructooligosaccharides plus mannanoligosaccharides on immune function and ileal and fecal microbial populations in adult dogs. Arch Tierernahr. 2002;56:309–18.

Sunvold GD, Fahey GC Jr, Merchen NR, Titgemeyer EC, Bourquin LD, Bauer LL, Reinhart GA. Dietary fiber for dogs: IV. In vitro fermentation of selected fiber sources by dog fecal inoculum and in vivo digestion and metabolism of fiber-supplemented diets. J Anim Sci. 1995;73:1099–109.

Flint HJ, Duncan SH, Scott KP, Louis P. Links between diet, gut microbiota composition and gut metabolism. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015;74:13–22.

Karr-Lilienthal LK, Grieshop CM, Spears JK, Patil AR, Czarnecki-Maulden GL, Merchen NR, Fahey GC. Estimation of the proportion of bacterial nitrogen in canine feces using diaminopimelic acid as an internal bacterial marker. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:1707–12.

Flickinger EA, Wolf BW, Garleb KA, Chow J, Leyer GJ, Johns PW, Fahey GC. Glucose-based oligosaccharides exhibit different in vitro fermentation patterns and affect in vivo apparent nutrient digestibility and microbial populations in dogs. J Nutr. 2000;130:1267–73.

Scholz-Ahrens KE, Schrezenmeir J. Inulin and oligofructose and mineral metabolism: the evidence from animal trials. J Nutr. 2007;137(Suppl 1):2513S–23S.

Beynen AC, Baas JC, Hoekemeijer PE, Kappert HJ, Bakker MH, Koopman JP, Lemmens AG. Faecal bacterial profile, nitrogen excretion and mineral absorption in healthy dogs fed supplemental oligofructose. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2002;86:298–305.

Ohta A, Ohtsuki M, Baba S, Adachi T, Sakata T, Sakaguchi E. Calcium and magnesium absorption from the colon and rectum are increased in rats fed fructooligosaccharides. J Nutr. 1995;125:2417–24.

Bach HJ, Tomanova J, Schloter M, Munch J. Enumeration of total bacteria and bacteria with genes for proteolytic activity in pure cultures and in environmental samples by quantitative PCR mediated amplification. J Microbiol Methods. 2002;49:235–45.

Malinen E. Comparison of real-time PCR with SYBR green I or 5′-nuclease assays and dot-blot hybridization with rDNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes in quantification of selected faecal bacteria. Microbiology. 2003;149:269–77.

Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Miyamoto Y, Takada T, Matsumoto K, Oyaizu H, Tanaka R. Development of 16S rRNA-gene-targeted group-specific primers for the detection and identification of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5445–51.

Collier CT, Smiricky-Tjardes MR, Albin DM, Wubben JE, Gabert VM, Deplancke B, Bane D, Anderson DB, Gaskins HR. Molecular ecological analysis of porcine ileal microbiota responses to antimicrobial growth promoters. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:3035–45.

Rinttilä T, Kassinen A, Malinen E, Krogius L, Palva A. Development of an extensive set of 16S rDNA-targeted primers for quantification of pathogenic and indigenous bacteria in faecal samples by real-time PCR. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:1166–77.

Wang RF, Cao WW, Franklin W, Campbell W, Cerniglia CE. A 16S rDNA-based PCR method for rapid and specific detection of Clostridium perfringens in food. Mol Cell Probes. 1994;8:131–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Effeffe Pet Food S.p.A. (Italy) for providing the commercial diets used in the present study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CP, CGV and CS carried out sample analysis. GB designed and supervised the study, carried out data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. CB, WW and GZ participated in the study design. CP, CGV and MG wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was carried out according to the Italian legislation implementing the European Council Directive 2010/63 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of the University of Bologna. Informed consent was obtained from all dog owners prior to the beginning of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pinna, C., Vecchiato, C.G., Bolduan, C. et al. Influence of dietary protein and fructooligosaccharides on fecal fermentative end-products, fecal bacterial populations and apparent total tract digestibility in dogs. BMC Vet Res 14, 106 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1436-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1436-x