Abstract

Background

Testicular tumours are common in dogs and in many cases do not give rise to clinical signs. In other cases, signs of feminization, hyperpigmentation or alopecia may be observed, most commonly associated with Sertoli cell tumours (SCT). Although these signs are often associated with elevated concentrations of oestradiol, analysis of oestradiol may give inconclusive results due to large variations among individuals. Other biomarkers are therefore needed. Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is expressed by the Sertoli cell. In humans, AMH has been shown to be a specific marker of Sertoli cell origin in gonadal tumours. Using immunohistochemistry, AMH has been shown to be a useful marker of immature and neoplastic Sertoli cells in dogs. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the clinical relevance of AMH analysis in peripheral blood in the diagnostic workup of dogs with suspected testicular tumours.

Results

Blood was collected from 20 dogs with a palpable testicular mass and from 27 healthy controls. Serum was analysed for oestradiol-17β using a RIA and for AMH using an ELISA. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare hormone concentrations between different groups.

All control dogs had AMH concentrations ≤ 10 ng/mL, except one outlier that had a concentration of 43 ng/mL. Six dogs with SCT or mixed tumours containing SCT had AMH concentrations higher than 22 ng/mL, significantly higher than AMH concentrations in control dogs (P = 0.0004). Concentrations between 10 and 22 ng/mL were found in about half of the dogs with non-neoplastic testicular pathologies or with testicular tumours other than SCTs. Age did not significantly affect concentrations of AMH in the control dogs.

Conclusion

AMH was shown to be a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of Sertoli cell tumours in dogs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Testicular tumours are common in dogs, more common than in other domestic species [1, 2]. In a study using the Norwegian Canine Cancer register (all histologically verified tumours submitted from veterinary practices within a defined area in Norway from predominantly intact dogs), 7.1 % of all tumours from male dogs were located in the testis [3]. In studies on unselected adult dogs submitted for routine autopsy, a prevalence of 16 % of testicular tumours was reported in 1962 [2], and 27 % in 2008 [4]. This may indicate an increasing prevalence in dogs, although other factors such as selection bias may contribute. In humans, an increasing incidence of testicular tumours has been described [5]. Poor semen quality, testis cancer, undescended testis and hypospadias have been proposed to be parts of the testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS) in humans, that is increasing due to environmental factors such as endocrine-disrupting chemicals [6]. Adverse environmental effects may lead to TDS also in intact dogs [7]. Another cause for a potentially increased prevalence of testicular tumours is genetic factors, as breed differences for both frequency and type of testicular tumours have been described [3]. The prevalence of different tumour types varies between studies, but Sertoli cell tumours (SCT), interstitial (Leydig) cell tumours (ICT), and Seminoma (SEM) are most common [2, 4, 8, 9]. Teratomas are rare [1, 2]. Cryptorchidism is associated with an increased risk of SCT and SEM [10].

Many tumours do not give rise to clinical signs except a palpable testicular mass, and of dogs with seminoma, less than one-third of cases were detectable at clinical examination [2]. Besides a palpable testicular mass, common clinical signs when present are feminization with gynecomastia, hyperpigmentation of the skin and bilateral alopecia. Infertility has been described [11]. These signs are observed mainly in dogs with Sertoli-cell tumours and occasionally also with Leydig cell tumours or seminoma [9, 12, 13]. Testicular tumours are rarely malignant, but when metastases occur they are most commonly found in the iliac lymph nodes and lungs [2, 14]. Bone marrow hypoplasia is a life-threatening condition associated with oestrogen production of tumours, most often SCT, and dogs may develop clinical signs related to bone marrow hypoplasia before the owner has noted other clinical signs related to oestrogen production [15]. Once dogs show clinical signs of bone marrow hypoplasia, the prognosis is guarded [15–17].

In mammals, the earliest specific protein expressed by Sertoli cells is Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), also called Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS), a glycoprotein that belongs to the transforming growth factor (TGF) β family [18]. Sertoli cells produce high concentrations of AMH from the time of testicular differentiation up to puberty, and the main effect is the regression of Müllerian ducts at the initiation of male sex differentiation [19]. In humans, AMH has been shown to be a specific marker of Sertoli cell origin in gonadal tumours [20]. In dogs, AMH was expressed in Sertoli cells from foetuses and pups up to day 45 [21]. Analysis of AMH has increasingly been used in human reproductive endocrinology over the last decade, primarily in the IVF settings, e.g. [22, 23]. In cattle AMH analysis has been useful to predict follicular and ovulatory response to gonadotrophin treatment for embryo transfer [24]. In dogs, AMH has been described to distinguish ovariohysterectomized from intact bitches [25].

A second generation ELISA for analysis of AMH, AMH Gen II (Beckman coulter), has been launched for commercial use. This assay uses the same antibodies as the assay previously used in dogs (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories), but with standards for the calibration curve from another assay (Immunotech) [22], and it measures AMH in human, monkey, bovine, dog and other mammalian species [25, 26]. The present study aimed at evaluating the clinical relevance for analysis of AMH in the diagnostic workup of dogs with alopecia or other clinical signs suspected to be associated with Sertoli cell tumours.

Methods

Dogs

In total, 20 dogs admitted for castration because of a palpable testicular mass and 27 healthy control dogs with both testicles descended in the testes and no testicular masses identified by palpation were included in the study. All dogs were five years or older and they were a subpopulation of a previous study [9].

The study was approved by the Local Animal Ethical Committee (M 63–09) and the Swedish Animal Welfare Agency (no. 31-2225/09, 31-2226/09). All owners signed informed consent.

Histology

Histopathological examination from dogs admitted for castration because of a testicular mass was done as previously described [9]. The testes were cut lengthwise and examined for macroscopic lesions. If lesions were present, tissue samples were taken from those areas and from areas with normal parenchyma. In testes without macroscopic lesions, tissue samples from three different sections of the testes were collected for microscopic evaluation, including cranial, central and caudal parts of the testis and the head of the epididymis. The tissue samples were fixed in 4 % neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned at 3 to 5 μm and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. The neoplastic changes were classified according to the WHO classification system for tumours of domestic animals [27].

Hormone analyses

Blood was collected and serum used for analysis of oestradiol-17β using a double antibody oestradiol radioimmunoassayFootnote 1 as previously described [9]. The upper reference limit was set at 40 pmol/L [9]. Serum levels of AMH were analysed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assayFootnote 2, according to the manufacturer. Briefly, 20 μL of standards, controls and samples were incubated in an anti-AMH antibody coated microtitration plate. After incubation and washing, anti-AMH biotin conjugate was added to each well. After a second incubation and washing step, streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase was added. After a third incubation and washing step, the substrate, tetramethylbenzidine was added and incubated briefly before adding an acidic stopping solution. The degree of enzymatic turnover of the substrate was determined by dual wavelength absorbance measurement at 450 nm and 620 nm. Samples with concentrations >22 ng/mL were diluted 1:10, 1:100 and 1:1000, if enough serum was available. The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was < 5 % and the inter-assay CV was <15 %.

Statistical analyses

For statistical analysis, the Mann–Whitney U test using Minitab statistical software was used for comparison between groups. Values are reported as median values and inter-quartile range (IQR). For correlations, the Spearman’s rank order correlation was used. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Dogs with palpable masses were of 15 different breeds and three mixed breed dogs, control dogs were of 17 different breeds and 7 mixed breed. In total, twenty-nine breeds were represented. No breed was represented by more than four dogs. The dogs with testicular masses had a median age (IQR) of 8.9 years (8.0-10.8). The control dogs were significantly (P < 0.001) younger, with a median age of 6.6 years (5.9-7.8).

Of the 20 dogs with palpable testicular masses, six had ICT, three had SEM, four had SCTs, three had mixed tumours (MIX), two of which contained SCT (MIX-SCT), and four had non-neoplastic pathologies (NNP). For details, see Table 1.

The median concentration of AMH in the 27 control dogs was 5.1 ng/mL (3.8-7.1). All control dogs had AMH concentrations ≤ 10 ng/mL, except for one outlier that had a concentration of > 22 ng/mL: 43 ng/mL. This dog was lost to follow-up. Age did not significantly affect concentrations of AMH in the control dogs (rs = 0.2, P = 0.2).

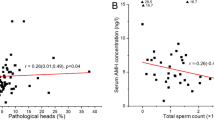

The six dogs with SCT or MIX-SCT had AMH concentrations above the highest standard point. In three of these dogs a further dilution was not possible, and in these dogs final concentrations are reported as 22 ng/mL. The six dogs with SCT or MIX-SCT had significantly higher concentrations of AMH (54.0 ng/mL, 22.0-66.0) than the control dogs (P = 0.0004). They also had higher AMH concentrations than the group of 14 dogs with other testicular tumours or NNP (12.0 ng/mL, 2.7-14.2). Of these 14 dogs 8 had AMH concentrations between 10 and 22 ng/mL (2/3 with SEM, 3/4 with NNP, 1/1 with MIX-non SCT, and 2/6 with ICT) (Table 1, Fig. 1). The AMH concentration did not differ significantly between dogs with ICT, SEM, or NNP (Table 2).

Three dogs had elevated oestradiol concentrations: one dog out of the six with SCT or MIX-SCT and two out of the six dogs with ICT (Table 1, Fig. 2). The median oestradiol concentration was 14.0 pmol/L (11.0-17.0) in the control dogs, and 18.5 pmol/L (8.5-51.3) in dogs with SCT and MIX-SCT. In the group of 14 dogs with other testicular tumours or NNP it was 11.5 pmol/L (7.8-20.2) (Table 2). The differences between the groups were not statistically significant. AMH concentration did not correlate significantly with oestradiol concentration (rs = 0.3, P = 0.07).

Discussion

The present study describes the value of analysing serum concentrations of AMH for diagnosing SCT. All dogs with SCT, including dogs with mixed tumours containing neoplastic Sertoli cells, had high (>22 ng/mL) concentrations of AMH, and in the three dogs in which further dilutions were possible, concentrations were found to be elevated from 4X to 1000X. An elevated serum concentration of AMH associated with SCT has previously been reported in a dog with non-pruritic alopecia [28]. The results of the present study and of that case report are in accordance with a previous study, using immunohistochemistry, reporting that AMH is a useful marker for immature and neoplastic canine Sertoli cells [21].

In a previous study on the canine testis, AMH was not expressed by Leydig cells, spermatogonia, interstitium or the epididymis [21]. In castrated male cats, the AMH concentration has been described to be below the detection limit [29]. In the present study, all control dogs, except for one outlier, had detectable AMH concentrations ≤ 10 pg/mL. AMH concentration did not differ significantly between control dogs and dogs with testicular tumours other than SCT or with NNP, but about half of dogs with these testicular changes had serum concentrations in the interval between 10 and 22 pg/mL. An increased expression of markers of immaturity in Sertoli cells, including AMH, has recently been described in cases of canine testicular atrophy [30]. Such changes may contribute to slightly elevated concentrations of AMH in some dogs with testicular pathologies other than SCT.

The control dogs were checked for palpable testicular masses and were clinically healthy, but no ultrasonography or histopathological examination of the testes was carried out because they were not castrated. This is a limitation of the study because minor testicular lesions cannot be ruled out. Sertoli cell tumours can be small and may not be detectable on a clinical examination, even if they give rise to clinical signs [2, 4, 11]. The range of AMH concentrations in dogs with no histopathological lesions may be narrower than the range found in the control dogs in the present study. The one control dog with a clearly elevated concentration of AMH most likely had a subclinical SCT. Unfortunately, this dog was lost to follow-up.

Another study limitation was that the control dogs were significantly younger than the dogs with testicular pathologies. However, age was not found to significantly affect AMH concentration in the control dogs. In humans, AMH concentrations have been described to decrease with age in older men although with large inter-individual variations [31]. It is thus highly unlikely that the increased AMH concentrations in dogs with testicular pathologies are related to age.

Oestradiol concentrations were high in one out of four dogs with SCT and in two out of six dogs with ICT. Whereas AMH is produced solely by Sertoli cells, increased production of oestradiol can be caused also by other testicular tumours but most commonly by SCTs [9, 12, 13]. In addition, serum oestradiol can be used as a part of an adrenal panel [32] because oestrogens not only are synthesized in the gonads, but also in the adrenals and in other tissues, such as skin and adipose tissue [33]. A substantial variability in oestradiol concentrations has been described both between and within castrated dogs [34]. Clinical signs of feminization may be associated with increased concentrations of oestradiol-17β or, more often, with a decreased testosterone/oestradiol ratio [9, 12]. There are thus several drawbacks with serum oestradiol analysis as a tool to diagnose SCT. To diagnose oestrogen producing tumours in dogs, preputial cytology may be an alternative [9].

There are several clinical implications of the study. In human medicine, AMH analysis has been described as a valuable tool to evaluate gonadal function in paediatric male hypogonadism [35–37] and Sertoli cell origin in gonadal tumours [20]. Testicular tumours that cause alopecia are not always associated with feminisation or increased concentration of oestradiol in dogs [9, 38], and even in cases of bone marrow suppression, clinical signs of feminisation may not be noticed by the owner [15]. In addition, oestradiol concentrations are not always elevated in cases with feminization [12]. Analysis of AMH may thus be useful in the diagnostic workup both of patients with dermatological problem and of patients with bone marrow suppression. Sertoli cells play a crucial role in spermatogenesis, and alterations in Sertoli cell function may lead to impaired spermatogenesis and male infertility. Non-palpable SCT have been associated with infertility in dogs [11]. Because AMH concentrations are increased in dogs with SCT, as shown in the present study, and an elevated expression of AMH has been described in testicular degeneration [30], analysis of AMH is of potential value in the diagnostic workup of dogs with reduced fertility. The one cryptorchid dog in the present study had a SCT, so the effect of cryptorchidism on AMH concentration could not be established. In horses, geldings have serum concentrations of AMH that are at or below the detection limit of the assay, whereas cryptorchid stallions have higher AMH concentrations than stallions with descended testes [39]. In cats, castrated males had AMH concentrations below the detection limit [29]. Analysis of AMH may be useful for determining if a dog is castrated or cryptorchid.

Conclusions

AMH is a biomarker for canine SCT, and can therefore be of value in the diagnostic work-up of e.g. male dogs with signs of feminisation, hyperpigmentation, alopecia, subfertility, infertility and bone marrow suppression. Further studies will be needed to verify reference intervals, because other testicular pathologies may also induce elevated concentrations of AMH, although generally lower than SCT.

Notes

coat-a-count, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics

AMH Gen II ELISA, Beckman coulter

Abbreviations

- AMH:

-

Anti-Müllerian hormone

- ICT:

-

Interstitial (Leydig) cell tumour

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

- MIX:

-

Mixed tumours

- MIX-SCT:

-

Mixed tumours containing SCT

- NNP:

-

Non-neoplastic pathology

- SCT:

-

Sertoli cell tumour

- SEM:

-

Seminoma

References

Reifinger M. Statistical studies of the occurrence of testicular neoplasms in domestic mammals. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A. 1988;35(1):63–72.

Dow C. Testicular tumours in the dog. J Comp Pathol. 1962;72:247–65.

Nodtvedt A, Gamlem H, Gunnes G, Grotmol T, Indrebo A, Moe L. Breed differences in the proportional morbidity of testicular tumours and distribution of histopathologic types in a population-based canine cancer registry. Vet Comp Oncol. 2011;9(1):45–54.

Grieco V, Riccardi E, Greppi GF, Teruzzi F, Iermano V, Finazzi M. Canine testicular tumours: a study on 232 dogs. J Comp Pathol. 2008;138(2–3):86–9.

Moller H. Trends in sex-ratio, testicular cancer and male reproductive hazards: are they connected? APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 1998;106(1):232–8. discussion 238–239.

Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Main KM. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: an increasingly common developmental disorder with environmental aspects. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(5):972–8.

Grieco V, Riccardi E, Veronesi MC, Giudice C, Finazzi M. Evidence of testicular dysgenesis syndrome in the dog. Theriogenology. 2008;70(1):53–60.

Liao AT, Chu PY, Yeh LS, Lin CT, Liu CH. A 12-year retrospective study of canine testicular tumors. J Vet Med Sci. 2009;71(7):919–23.

Dreimanis U, Vargmar K, Falk T, Cigut M, Toresson L. Evaluation of preputial cytology in diagnosing oestrogen producing testicular tumours in dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2012;53(9):536–41.

Reif JS, Maguire TG, Kenney RM, Brodey RS. A cohort study of canine testicular neoplasia. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1979;175(7):719–23.

England GC. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of non-palpable Sertoli cell tumours in infertile dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 1995;36(11):476–80.

Mischke R, Meurer D, Hoppen HO, Ueberschar S, Hewicker-Trautwein M. Blood plasma concentrations of oestradiol-17beta, testosterone and testosterone/oestradiol ratio in dogs with neoplastic and degenerative testicular diseases. Res Vet Sci. 2002;73(3):267–72.

Peters MA, de Jong FH, Teerds KJ, de Rooij DG, Dieleman SJ, van Sluijs FJ. Ageing, testicular tumours and the pituitary-testis axis in dogs. J Endocrinol. 2000;166(1):153–61.

Gopinath D, Draffan D, Philbey AW, Bell R. Use of intralesional oestradiol concentration to identify a functional pulmonary metastasis of canine sertoli cell tumour. J Small Anim Pract. 2009;50(4):198–200.

Sherding RG, Wilson 3rd GP, Kociba GJ. Bone marrow hypoplasia in eight dogs with Sertoli cell tumor. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1981;178(5):497–501.

Kasbohm C, Saar C. [Bone-marrow damage due to estrogen in dogs with testicular neoplasms]. Tierarztliche Praxis. 1975;3(2):225–9.

Edwards DF. Bone marrow hypoplasia in a feminized dog with a Sertoli cell tumor. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1981;178(5):494–6.

Josso N, di Clemente N. TGF-beta Family Members and Gonadal Development. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 1999;10(6):216–22.

Josso N, di Clemente N, Gouedard L. Anti-Mullerian hormone and its receptors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;179(1–2):25–32.

Rey R, Sabourin JC, Venara M, Long WQ, Jaubert F, Zeller WP, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone is a specific marker of sertoli- and granulosa-cell origin in gonadal tumors. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(10):1202–8.

Banco B, Veronesi MC, Giudice C, Rota A, Grieco V. Immunohistochemical evaluation of the expression of anti-Mullerian hormone in mature, immature and neoplastic canine Sertoli cells. J Comp Pathol. 2012;146(1):18–23.

Nelson SM, La Marca A. The journey from the old to the new AMH assay: how to avoid getting lost in the values. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23(4):411–20.

Brodin T, Hadziosmanovic N, Berglund L, Olovsson M, Holte J. Antimullerian hormone levels are strongly associated with live-birth rates after assisted reproduction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1107–14.

Rico C, Drouilhet L, Salvetti P, Dalbies-Tran R, Jarrier P, Touze JL, et al. Determination of anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations in blood as a tool to select Holstein donor cows for embryo production: from the laboratory to the farm. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2012;24(7):932–44.

Place NJ, Hansen BS, Cheraskin JL, Cudney SE, Flanders JA, Newmark AD, et al. Measurement of serum anti-Mullerian hormone concentration in female dogs and cats before and after ovariohysterectomy. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23(3):524–7.

Kumar A, Kalra B, Patel A, McDavid L, Roudebush WE. Development of a second generation anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) ELISA. J Immunol Methods. 2010;362(1–2):51–9.

Kennedy PC, Cullen JM, Edwards JF, Goldschmidt MH, Larsen S, Munson L, et al. Histological classification of tumors of the genital system of domestic animals. In: World health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumors of Domestic Animals. Volume IV, 2 edn. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of pathology; 1998. p. 17–8.

Ano H, Hidaka Y, Katamoto H. Evaluation of anti-Mullerian hormone in a dog with a Sertoli cell tumour. Vet Dermatol. 2014;25(2):142–5. e141.

Axner E, Strom Holst B. Concentrations of anti-Mullerian hormone in the domestic cat. Relation with spay or neuter status and serum estradiol. Theriogenology. 2015;83(5):817–21.

Giudice C, Banco B, Veronesi MC, Ferrari A, Di Nardo A, Grieco V. Immunohistochemical expression of markers of immaturity in sertoli and seminal cells in canine testicular atrophy. J Comp Pathol. 2014;150(2–3):208–15.

Chong YH, Dennis NA, Connolly MJ, Teh R, Jones GT, van Rij AM, et al. Elderly men have low levels of anti-Mullerian hormone and inhibin B, but with high interpersonal variation: a cross-sectional study of the sertoli cell hormones in 615 community-dwelling men. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70967.

Frank LA, Rohrbach BW, Bailey EM, West JR, Oliver JW. Steroid hormone concentration profiles in healthy intact and neutered dogs before and after cosyntropin administration. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2003;24(1):43–57.

Nelson LR, Bulun SE. Estrogen production and action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(3 Suppl):S116–124.

Frank LA, Mullins R, Rohrbach BW. Variability of estradiol concentration in normal dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2010;21(5):490–3.

Grinspon RP, Rey RA. New perspectives in the diagnosis of pediatric male hypogonadism: the importance of AMH as a Sertoli cell marker. Arquivos brasileiros de endocrinologia e metabologia. 2011;55(8):512–9.

Josso N, Rey RA, Picard JY. Anti-mullerian hormone: a valuable addition to the toolbox of the pediatric endocrinologist. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:674105.

Matuszczak E, Hermanowicz A, Komarowska M, Debek W. Serum AMH in Physiology and Pathology of Male Gonads. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:128907.

Siegel ET, Forchielli E, Dorfman RI, Brodey RS, Prier JE. An estrogen study in the feminized dog with testicular neoplasia. Endocrinology. 1967;80(2):272–7.

Claes A, Ball BA, Almeida J, Corbin CJ, Conley AJ. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations in stallions: developmental changes, seasonal variation, and differences between intact stallions, cryptorchid stallions, and geldings. Theriogenology. 2013;79(9):1229–35.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Ms Rosemarie Klausson for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

UD coordinated the clinical and pathological examinations. BSH coordinated AMH analyses, conceived of the study, and drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Holst, B.S., Dreimanis, U. Anti-Müllerian hormone: a potentially useful biomarker for the diagnosis of canine Sertoli cell tumours. BMC Vet Res 11, 166 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-015-0487-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-015-0487-5