Abstract

Background

Community hospitals provide the majority of patient care in Canada but traditionally do not participate in clinical research. The disconnect between where most patients receive their health care and where health research is conducted leads to decreased study recruitment, reduced generalizability of study results, and inequitable patient access to novel therapies. A scoping review of the research activities of Ontario’s large community hospitals (LCHs) between 2013 and 2015 reported an annualized output of 266 publications. In the last decade, efforts have been made to engage more community hospitals in research. In this updated scoping review, we provide a snapshot of the research activities of Ontario’s LCHs between 2016 and 2022, describing the number and type of research publications as well as the frequency of collaboration within and between LCHs.

Methods

Three medical databases (PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL) were searched for publications that included at least one author affiliated with one of Ontario’s 47 LCHs, and for which the topic was hospital or health related. Screening and extraction occurred concurrently.

Results

We identified 3,719 publications from 2016 to 22 with at least one Ontario LCH-affiliated author, representing an annualized output of 531 publications. The most frequent publication type was observational study (n = 1,654; 45%), quality improvement (n = 355; 10%), systematic reviews (n = 352; 9%) and randomized controlled trials (n = 325; 9%). The most common disciplines were outpatient care (n = 1,144; 31%), health systems research (n = 806; 22%), inpatient care (n = 437; 12%) and surgery (n = 403; 11%). LCH-affiliated first authors were identified in 997 (27%) publications, representing 755 unique authors, while LCH-affiliated senior authors were identified in 962 (26%) publications, representing 583 unique authors. Among the 1,565 studies with an LCH-affiliated first or senior author, 574 (37%) included collaborators from the same LCH and 86 (5%) included collaborators from other Ontario LCHs.

Conclusions

Health research by LCH-affiliated clinicians and researchers increased significantly in 2016–2022 relative to 2013–2015. Participation in randomized controlled trials however, remains low, suggesting that further efforts are required to build clinical research infrastructure in LCHs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Canadian hospitals are classified as academic (teaching) or community (non-teaching) [1]. Academic hospitals traditionally regard teaching and research as key aspects of their mission, whereas community hospitals focus on health service delivery [2]. Community hospitals in Canada have 46,448 patient beds, whereas academic hospitals have 23,944 beds [2]. Community hospitals provide the majority of patient care in Canada, representing 90% of hospitals nationwide [1], and 75% of hospitals in the province of Ontario, Canada’s most populous province [3]. Over the past decade, the decentralization of medical education through regional medical campuses has increased community hospital engagement in education and scholarly activities [4, 5]. However, research productivity in community hospitals lags far behind that of academic hospitals [6]. The siloed approach to health service delivery and research hinders study recruitment, decreases the generalizability of study results, and delays study completion [2, 7,8,9]. It also leads to inequitable patient access to novel therapies [10]. Studies have confirmed that academic and community hospital patients differ with respect to sociodemographic factors [11,12,13,14], clinical characteristics, and hospital outcomes [14]. Thus, increasing community hospital research participation has the potential to increase the diversity of study participants and improve the generalizability of study results by reflecting a broader set of patients and care settings.

The importance of engaging community hospitals in research was highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Data from the Ontario Ministry of Health revealed that 75% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Ontario received their care in community hospitals [7]. Yet, only 10% of Ontario’s community hospitals (13/124) participated in the flagship Canadian Treatments for COVID-19 (CATCO) trial [15], limiting study recruitment and slowing completion. By comparison, 80% of National Health Service (NHS) trusts (176/219) in the United Kingdom participated in the Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) Trial [16]. Including community hospitals in research has been shown to accelerate knowledge translation [17] and generate locally relevant findings [2]. It is also associated with improved patient outcomes [18,19,20]. Furthermore, research participation enhances clinical staff satisfaction and retention [2, 9, 17], improves organizational efficiency [9, 17], and creates revenue opportunities for the hospital [9].

In 2017, DiDiodato and colleagues [6] published a scoping review of the research publications of Ontario’s large community hospitals (LCHs) from 2013 to 2015. Total publications from 44 LCHs were 798 publications, representing an annual output of 266 publications [6]. Over the past decade, however, the healthcare landscape in Canada has evolved and significant efforts have been made to expand research capacity in community hospitals [2, 7,8,9, 21, 22]. For example, in a separate article [9] it was identified that there was significant growth in the number of clinical trials and observational studies initiated at the 10 largest community hospitals in Ontario. Additionally, grassroots initiatives such as the Canadian Community ICU Research Network and the COVID-19 Network of Clinical Trials Networks, led by the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group, have been developed to provide mentorship and financial support to help community hospitals build their research programs [22]. Thus, the aim of this updated scoping review was to provide a recent snapshot of the research activit in Ontario’s LCHs from 2016 to 2022 and to compare it with data from 2013 to 2015.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted using the methodological framework of Arksey and O’Malley [23] with recommendations by Levac et al. [24]. Scoping reviews are ideal for mapping out the extent, range, and nature of research activities to identify existing gaps within the literature and inform planning for future research [23, 25].

Identifying the research question

The research question was adapted from DiDiodato et al.’s [6] 2017 review and guided by the Population, Context, Concept framework for scoping review questions [26]: What are the extent, type and collaborative nature of Ontario LCHs’ research activities from 2016 to 2022?

Search strategy and study selection

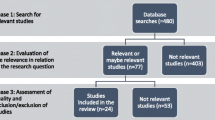

An updated search strategy was developed in consultation with a librarian at Brock University (IDG). Guided by the databases selected in the initial scoping review, three medical databases (PubMed, Embase, and the CINAHL) were systematically searched for research publications from January 1st, 2016 to December 31st, 2022. An updated list of Ontario’s public hospitals was obtained from the Ontario Hospital Association and 47 hospitals with “large community hospital” status were included in the search. To capture all research activities and output, all publication types whose author(s) were affiliated with any of the 47 LCHs were included. LCHs are defined by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care as hospitals with 2,700 or more acute and day-surgery weighted cases in any two of the prior three years [27]. The authors’ professional designation was not relevant to inclusion, as supported by DiDiodato et al. [6]. Publications were excluded if none of the authors were affiliated an Ontario LCH, or if the study was not hospital or medicine/health sciences related. Additionally, publications that were exclusively corrections to previously published work were excluded.

Types of publications were categorized as: review articles (i.e. scoping, narrative, systematic review and meta-analyses), case reports, editorials, guidelines, observational studies (i.e. retrospective chart review, prospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies), position papers, study protocols, qualitative studies, quality improvement studies, and randomized controlled trials (RCT). Disciplines were categorized as: allied health, emergency medicine, family medicine, health systems research, intensive care, pediatrics, psychiatry, surgery, outpatient care, inpatient care, and basic science. Inpatient care was defined as any study relating to hospitalized inpatients, excluding those in the intensive care unit. Outpatient care was defined as any study relating to non-hospitalized patients (i.e. oncology, radiology, nephrology, rheumatology). LCH collaboration was categorized as occurring within the same LCH, between LCHs, or both within and between LCHs, as determined by author affiliations.

One member of the research team (KR) conducted the literature search as follows. Each database was searched by LCH name using the ‘affiliation’ field, followed by the ‘year’ filter set to 2016–2022. Variations of LCH name and individual hospital site names were included in the search string (where applicable) for maximal retrieval (Additional File 1). All of the publications were uploaded to Covidence [28] and duplicates were removed. Data on the remaining publications (publication title, digital object identifier, authors and year) were exported to Microsoft Excel [29]. A random sample of 10 articles was selected and independently screened and extracted by 4 members of the research team (KR, PP, AN, MB) to ensure consistency. The remaining articles were divided among the 4 research team members for concurrent screening and extraction.

Charting the data

Screening and extraction occurred concurrently. The variables extracted included the names of authors with LCH affiliation(s), the LCH affiliation(s), year of publication, publication type, and discipline/research focus.

Collecting, summarizing and reporting results

Data were compiled, cleaned, and analyzed by one member of the research team (JJ). Results were described using descriptive statistics and data visualization tools, and reported in accordance the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Additional File 2).

Results

A search of three medical databases yielded 6,730 publications, after duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). Of these, 3,719 had at least one author affiliated with one of Ontario’s 47 LCHs.

Research publications

Of the 47 Ontario LCHs, 46 had at least one publication from an affiliated author during the study period. The number of annual publications from Ontario LCHs increased continuously over the study period from 407 in 2016 to 673 in 2022, averaging a 9% annual rate of increase in total publications (Fig. 2). The mean annual research output for all of the Ontario LCHs during the study period was 531.

Publication types and study disciplines

The majority of publications were full-text, peer-reviewed articles (n = 3,136; 84%) as opposed to published abstracts (n = 583; 16%). The most common publication types were observational studies (n = 1,654; 45%), followed by quality improvement (n = 355; 10%), systematic reviews (n = 352; 9%), RCTs (n = 325; 9%), editorials (n = 305; 8%), qualitative research (n = 236; 6%), guidelines (n = 232; 6%), case reports (n = 140; 4%), position papers (n = 49; 1%), and basic science (n = 37; 1%). The number of RCTs published per year remained relatively stable during the study period, with an increase observed in 2022 (Fig. 3). The most common study disciplines were outpatient care (n = 1,144; 31%), followed by health systems research (n = 806; 22%), inpatient care (n = 437; 12%), and surgery (n = 403; 11%).

Authorship & collaboration

Across all articles, 708 (19%) displayed collaboration within the same LCH, 243 (7%) displayed collaboration between two or more Ontario LCHs, and 71 (2%) displayed collaboration both within and between Ontario LCHs. The remaining 2,697 (73%) publications involved only a single LCH-affiliated author, with all other authors being affiliated with academic institutions.

With respect to first and senior (i.e. last) LCH-affiliated authorship, 997 (27%) publications had an LCH-affiliated first author, representing 755 unique first authors, and 962 (26%) studies had an LCH-affiliated senior author, representing 583 unique senior-authors. In total, there were 1,565 studies with either an LCH-affiliated first-author or senior-author. Amongst the 1,565 studies with LCH-affiliated first or senior authors, 574 (37%) included collaborators from the same LCH and 86 (5%) included collaborators from other Ontario LCHs. Remaining publications involved collaborators affiliated with non-LCH institutions.

Discussion

This scoping review provides an updated overview of the extent, type and collaborative nature of research activities within Ontario’s acute care LCHs, as derived from published articles. The results demonstrate a significant increase in LCH-affiliated research output between 2013-2015 and 2016–2022, highlighted by a more than tripling of research productivity over this ten-year period. Specifically, annual publications increased from 210 in 2013 to 673 in 2022, representing an average annual increase of 14% in total publications. Notably, DiDiodato’s 2017 review included only 44 LCHs, as opposed to 47 in this review. Moreover, only 39/44 (84%) LCHs had at least one publication from 2013 to 2015, whereas 46/47 (98%) LCHs in this review had at least one publication from 2016 to 2022 [6]. Both reviews reported that observational studies were the most common publication type and outpatient speciality care was the most common research area. RCTs represented a relatively small percentage of LCH-affiliated publications in both 2013–2015 (4.3% in 2013; 10% in 2014; 10.3% in 2015) and 2016–2022 (9%) [6]. However, LCH participation in RCTs did increase in 2022, which may reflect ongoing efforts to engage community hospitals in COVID-19 therapeutic studies [7, 30]. With respect to collaborations, we found that authors affiliated with LCHs led 27% and 26% of research publications as first and senior authors, respectively, which varies from 35% to 16% in 2013–2015 [6]. There is also a tendency for LCH-affiliated authors to collaborate with authors affiliated with academic institutions. This finding is consistent with previous research that shows most clinical research is conducted at academic centres [2, 6].

This scoping review provides an overview of the research activities of Ontario’s LCHs from 2016 to 2022, using the number of research publications with LCH-affiliated authors as a proxy for LCH research productivity [6]. It is important, however, to consider the limitations of this approach. Since author affiliations are self-reported, it is uncertain whether affiliations reflect actual place of work. Thus, individuals working in LCHs may be publishing with academic affiliations rather than their LCH affiliation. Additionally, there are variations in how LCH names are listed (e.g. use of hospital name versus hospital corporation name) that may have resulted in publications being missed. Although we aimed to maximize sensitivity by including known variations, it is possible that some were missed.

Overall, our results demonstrate a steady increase in research productivity among Ontario’s LCHs. Recent reports have emphasized the benefits of expanding community hospital research capacity, but have also identified significant barriers to this expansion, including the absence of research infrastructure, limited research experience among community hospital clinical staff, and the lack of research culture [2, 7,8,9, 21]. Existing funding models for health research assume that hospitals have research experience and infrastructure [2, 6, 9], and do not provide additional funding for hospitals without these prerequisites. Moreover, community hospitals are not historically expected to participate in health research [9], and there are limited institutional incentives [7]. Despite these barriers, the remarkable increase in LCH-affiliated research output over the past decade illustrates growing engagement and highlights the untapped potential of community hospital research participation [8, 31, 32] as a means of increasing study enrolments, improving the generalizability of study results, and ensuring patient access to research studies. Areas for improvement include fostering collaborations between community hospital researchers and encouraging community hospital researchers to lead studies that are relevant to the needs of their local patient populations [9]. In addition, there is a need to build capacity for RCT participation, as these require specialized infrastructure and an experienced clinical research team [33]. Ultimately, to achieve a true learning health system, the Canadian healthcare system needs to invest in dedicated infrastructure to facilitate community hospital participation in research and establish policies that embed research within health service delivery.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LCH:

-

Large Community Hospital

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- CATCO:

-

Canadian Treatments for COVID-19

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- RECOVERY:

-

Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hospital Beds Staffed and In Operation 2020–2021 [Internet]. 2022. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjUsJC03qKBAxUTAjQIHQ-iCWIQFnoECB0QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cihi.ca%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fdocument%2Fbeds-staffed-and-in-operation-2020-2021-en.xlsx&usg=AOvVaw1MA_XDmKP5eZLf_jSkRX6V&opi=89978449.

Gehrke P, Binnie A, Chan SPT, Cook DJ, Burns KEA, Rewa OG, et al. Fostering community hospital research. CMAJ. 2019;191(35):E962–6.

Ontario Hospital Association. Ontario’s Hospitals [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 12]. https://www.oha.com/about-oha/Ontario-Hospitals

Bell A, Khemani E, Weera S, Henderson C, Chambers LW. Energizing scholarly activity in a regional medical campus. Can Med Ed J [Internet]. 2021 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Sep 14]; https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cmej/article/view/72593

Cathcart-Rake W, Robinson M. Promoting Scholarship at Regional Medical Campuses. JRMC [Internet]. 2018 Jan 11 [cited 2023 Sep 14];1(1). https://pubs.lib.umn.edu/index.php/jrmc/article/view/999

DiDiodato G, DiDiodato JA, McKee AS. The research activities of Ontario’s large community acute care hospitals: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):566.

Tsang JLY, Fowler R, Cook DJ, Ma H, Binnie A. How can we increase participation in pandemic research in Canada? Can J Anaesth. 2021;69(3):293–7.

Tsang JLY, Fowler R, Cook DJ, Burns KEA, Hunter K, Forcina V, et al. Motivating factors, barriers and facilitators of participation in COVID-19 clinical research: a cross-sectional survey of Canadian community intensive care units. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(4):e0266770.

Snihur A, Mullin A, Haller A, Wiley R, Clifford P, Roposa K, et al. Fostering Clinical Research in the Community Hospital: opportunities and Best practices. Healthc Q. 2020;23(2):30–6.

Acuña-Villaorduña A, Baranda JC, Boehmer J, Fashoyin-Aje L, Gore SD. Equitable Access to Clinical Trials: How Do We Achieve It? American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 2023;(43):e389838.

Carmen T. Visible minorities now the majority in 5 B.C. cities. CBCNews [Internet]. 2017; https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/visible-minorities-now-the-majority-in-5-b-c-cities-1.4375858

Fleet RMD, PhD, Audette LDMD, Marcoux J, Villa J, Archambault PMD, MSc, Poitras JMD. Comparison of access to services in rural emergency departments in Quebec and British Columbia. CJEM: Journal of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. 2014;16(6):437–48.

Fleet R, Pelletier C, Marcoux J, Maltais-Giguère J, Archambault P, Audette LD, et al. Differences in Access to services in Rural Emergency Departments of Quebec and Ontario. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0123746.

Tsang JLY, Binnie A, Duan EH, Johnstone J, Heels-Ansdell D, Reeve B, et al. Academic and Community ICUs participating in a critical Care Randomized Trial: a comparison of patient characteristics and Trial Metrics. Crit Care Explor. 2022;4(11):e0794.

Ali K, Azher T, Baqi M, Binnie A, Borgia S, Carrier FM, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of patients in hospital with COVID-19 in Canada: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2022;194(7):E242–51.

Wise J, Coombes R. Covid-19: the inside story of the RECOVERY trial. BMJ. 2020;370:m2670.

Harding K, Lynch L, Porter J, Taylor NF. Organisational benefits of a strong research culture in a health service: a systematic review. Aust Health Rev. 2017;41(1):45.

Majumdar SR. Better Outcomes for Patients Treated at hospitals that participate in clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(6):657.

Rochon J, Du Bois A. Clinical research in epithelial ovarian cancer and patients’ outcome. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:vii16–9.

Du Bois A, Rochon J, Lamparter C, PFisterer J. Pattern of care and impact of participation in clinical studies on the outcome in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15(2):183–91.

Wang M, Dolovich L, Holbrook A, Jack SM. Factors that influence community hospital involvement in clinical trials: a qualitative descriptive study. Evaluation Clin Pract. 2022;28(1):79–85.

Rego K, Binnie A, Sheikh F, Tsang J. Why every Canadian hospital should be a ‘research’ hospital [Internet]. Healthy Debate. 2024. https://healthydebate.ca/2024/04/topic/canadian-research-hospital/

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Grimshaw JA. Knowledge Synthesis Chapter [Internet]. CIHR; https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/knowledge_synthesis_chapter_e.pdf

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [Internet]. JBI; 2020 [cited 2023 Dec 7]. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687342/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews

Large Community Hospital Operations. (Sect. 3.08, 2016 Annual report of the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario). Toronto: Standing Committe on Public Accounts; 2018.

Covidence. [Internet]. https://www.covidence.org

Excel [Internet]. Microsoft; https://www.microsoft.com/en-ca/microsoft-365/excel

Lamontagne F, Rowan KM, Guyatt G. Integrating research into clinical practice: challenges and solutions for Canada. CMAJ. 2021;193(4):E127–31.

Begg CB, Carbone PP, Elson PJ, Zelen M. Participation of Community hospitals in clinical trials: analysis of five years of experience in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(18):1076–80.

Tsang JLY, Binnie A, Farjou G, Fleming D, Khalid M, Duan E. Participation of more community hospitals in randomized trials of treatments for COVID-19 is needed. CMAJ. 2020;192(20):E555.

Dimond EP, St. Germain D, Nacpil LM, Zaren HA, Swanson SM, Minnick C, et al. Creating a culture of research in a community hospital: strategies and tools from the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program. Clin Trails. 2015;12(3):246–56.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Maiya Bolibruck at Brock University, for assistance with data extraction and Ian D. Gordon, Brock University Library Teaching & Learning Librarian, for assistance with database selection, searching, screening and citation management.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T., A.B., and G.D. conceived the study. K.R. conducted the literature search. K.R., P.P. and A.N. independently screened the articles and extracted the data. J.J. analyzed the data. J.J., K.R., P.P., A.B. and J.T. contributed to writing and critically revising the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

J.T., A.B., and G.D. are clinician-researchers in community hospital settings. J.T. received funding from the Physician Services Incorporated (PSI) foundation for a separate qualitative study focused on building community hospital research capacity.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rego, K., Jomy, J., Patel, P. et al. The research activities of Ontario’s large community hospitals: an updated scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 1137 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11454-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11454-6