Abstract

Background

Rural populations experience ongoing health inequities with disproportionately high morbidity and mortality rates, but digital health in rural settings is poorly studied. Our research question was: How does digital health influence healthcare outcomes in rural settings? The objective was to identify how digital health capability enables the delivery of outcomes in rural settings according to the quadruple aims of healthcare: population health, patient experience, healthcare costs and provider experience.

Methods

A multi-site qualitative case study was conducted with interviews and focus groups performed with healthcare staff (n = 93) employed in rural healthcare systems (n = 10) in the state of Queensland, Australia. An evidence-based digital health capability framework and the quadruple aims of healthcare served as classification frameworks for deductive analysis. Theoretical analysis identified the interrelationships among the capability dimensions, and relationships between the capability dimensions and healthcare outcomes.

Results

Seven highly interrelated digital health capability dimensions were identified from the interviews: governance and management; information technology capability; people, skills, and behaviours; interoperability; strategy; data analytics; consumer centred care. Outcomes were directly influenced by all dimensions except strategy. The interrelationship analysis demonstrated the influence of strategy on all digital health capability dimensions apart from data analytics, where the outcomes of data analytics shaped ongoing strategic efforts.

Conclusions

The study indicates the need to coordinate improvement efforts targeted across the dimensions of digital capability, optimise data analytics in rural settings to further support strategic decision making, and consider how consumer-centred care could influence digital health capability in rural healthcare services. Digital transformation in rural healthcare settings is likely to contribute to the achievement of the quadruple aims of healthcare if transformation efforts are supported by a clear, resourced digital strategy that is fit-for-purpose to the nuances of rural healthcare delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Continuing significant health inequalities exist within and across countries [1]. In Australia, people in rural and remote areas have a 40% increased disease risk and a 2.3 times higher preventable mortality rate than those in major cities [2]. First Nations Australians are particularly disadvantaged: those living in remote areas have a life expectancy 6–7 years lower than those in major cities [3]. The population is unevenly dispersed across vast distances and harsh environments, contributing to healthcare access issues [4].

In these rural settings, geographic, resourcing and health equity challenges provide great opportunity for digital models of care [5]. Precision medicine and virtual care hold the promise of more integrated and value-based health systems with improved outcomes and care closer to home [6]. Outcomes are increasingly measured and mapped using the quadruple aim of healthcare: population health, patient experience, healthcare costs and provider experience [7]. The quadruple aim enables a balanced view of healthcare outcomes beyond traditionally measured productivity measures to benefits that are meaningful to staff, clinicians and consumers [8].

Literature on digital health transformation acknowledges the disparities faced by rural communities and their difficulty in delivering on the quadruple aim of healthcare given geographic constraints [9,10,11]. Although digital adoption across healthcare settings varies [12], the need for digital health is highest in rural and resource-constrained settings [13]. Rural areas need more reliable digital connectivity to compensate for the geographical remoteness, yet rural communities are generally less and worse connected by technologies [10]. Described as a digital vulnerability [10], rurality is contributing to widening digital health inequities [9]. Careful consideration of transformation efforts is required to ensure the unanticipated consequences [8] such as exacerbating the rural digital divide, are adequately managed [10, 14]. ‘TechQuity’ has become an increasingly prioritised commitment to use technology to eliminate structural inequities among diverse social, economic, demographic or geographic groups [14]. Although enormous efforts are currently underway to bring digital services to rural and remote areas, challenges remain in supporting an ageing and understaffed rural workforce [15] to adopt digitally-enabled models of care with immature infrastructure, network fragility, public policy constraints, adoption barriers, lack of digital devices, constrained local technical knowledge, and variable digital inclusion of citizens [9,10,11].

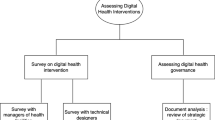

Digital health capability refers to the enabling environment required for executing digital health [16]. Digital health capability (or ‘maturity’) assessments examine the enabling environment across groups of variables often referred to as dimensions [16,17,18]. Despite the interest of digital transformation leaders to define clear targets for success, and the many frameworks available to assess digital health capability (e.g., Electronic Medical Record Adoption Model, Picture Archiving and Communication Systems Maturity Model, Clinical Digital Maturity Index) [17], international consensus on how digital health capability should be measured remains elusive [19]. Digital capability assessments have traditionally focused on technical implementation alone [19]. To consolidate the diverse dimensions, we conducted a systematic literature review and developed a synthesised digital health capability framework [17], and refined it through a consultative process with various healthcare stakeholders [18] (Fig. 1). This framework provides health organisations with a more comprehensive understanding of the current state of digital health capability and guidelines to develop roadmaps for digital health to result in meaningful improvement in patient care, health outcomes and health equity. While building digital health capability can positively contribute to the health equity gap [20], the digital health capability of rural and remote health services is poorly studied.

Previous research suggests the need for healthcare organisations to improve digital health capability [19] with calls for research to investigate: (1) digital health capability in resource-constrained rural health services [12, 13, 21], (2) the interrelationships among the different dimensions of digital health capability [17], and (3) the outcomes that meaningfully benefit patients and populations [17, 21, 22]. To address this gap, we sought to answer the research question: How does digital health capability influence healthcare outcomes in rural settings according to the quadruple aims of healthcare?

Our objectives were to:

-

1.

Identify digital health capability dimensions in rural settings.

-

2.

Identify the relationships among the digital health capability dimensions and healthcare outcomes.

-

3.

Identify the interrelationships among the digital health capability dimensions.

Methods

A multi-site qualitative case study was conducted, using semi-structured interviews supplemented with focus groups.

Setting and participants

In the geographically large Australian state of Queensland, approximately 38% of the total population and 66% of First Nations people live in non-metropolitan areas [4]. Universal healthcare is delivered by Queensland Health across 16 geographically defined healthcare systems, providing a range of public healthcare services in small rural clinics to large quaternary academic hospitals [23]. Of the 16 healthcare systems, six are considered regional as they have a mix of regional, rural and remote healthcare services and four are considered remote as they serve only rural and remote communities [23, 24] (Fig. 2). Queensland Health’s ten-year digital strategic plan includes the vision to improve access to care and support better health outcomes for rural and remote Queenslanders [2]. Regional (n = 6) and remote (n = 4) healthcare systems were included in this study and are collectively referred to as rural healthcare systems (n = 10).

Data collection

As digital transformation is an interdisciplinary endeavour, a purposive sample [25] of healthcare staff working in diverse roles (e.g., clinicians, executives, informatics team members) within rural healthcare systems were eligible participants. Site contact persons and the state-wide health executive forum helped identify participants. Participants were invited to attend an interview or focus group via videoconferencing and a semi-structured interview guide was administered by two interviewers. The interview guide contained questions pertaining to strategic vision, experiences of implementations, and evaluations of digital transformations, tailored to each professional group (Appendix 1). Participation was voluntary. Interviews and focus groups were audio recorded, transcribed, and anonymised.

Data analysis

The interview data was deductively analysed using the digital health capability framework [18] and quadruple aims of healthcare [7] as classification frameworks. The analysis involved two researchers coding the interview data and classifying the relevant perceptions of interview participants to the respective subdimensions of digital health capability and healthcare outcomes. Through an initial qualitative analysis, there were consistency amongst the themes described by regional and remote healthcare systems and therefore the analysis was performed on the combined sample. When the analysis revealed a theme not included in the existing framework [18] it was inductively analysed [26]. Three new sub-dimensions resulted: resources (governance and management dimension); fit-for-purpose (IT capability dimension); and attitudes (people, skills and behaviour dimension) (Fig. 1, Appendix 2).

The quadruple aims of healthcare was used to identify the outcomes related to population health (e.g., equity, access, disparities), patient experience (e.g., preferences, communication, access, engagement), provider experience (e.g., workload, preferences), and healthcare costs (i.e., resourcing, efficiency) [7, 27].

To address objective 1, the analysis of the quotes regarding the sub-dimensions and dimensions of the digital health capability framework were synthesised in tables and reported narratively. We did not identify divergent perspectives in this analysis.

To address objective 2 and 3, theoretical coding was performed to identify relationships between the dimensions of the digital health capability framework and outcomes (e.g., between interoperability and population health) and interrelationships among the dimensions (e.g., between interoperability and strategy), respectively. The analyses for objectives 2 and 3 were supported by the matrix querying functionality in NVivo (version 12, QSR International). The outputs of the matrix queries were manually analysed by four researchers to confirm the relationships, and to identify the direction of the relationship.

In all analyses, findings were refined and finalised through consensus in researcher workshops [25].

Results

In total, 93 participants attended an interview or focus group across regional (n = 6) and remote (n = 4) healthcare systems (Table 1).

Perceptions of rural digital health capability

The perceptions of digital health capability dimensions in rural healthcare systems are described below. Three new sub-dimensions were identified; resources (governance and management dimension); fit-for-purpose (IT capability dimension); and attitudes (people, skills and behaviour dimension). Appendix 3 provides additional evidence of the capability subdimensions.

Consumer-centred care, in terms of supporting consumers to manage their own health through technology-enhanced care and improved consumer health literacy, was valued by participants: “Communication with patients, so the ability to send text messages or have an app that allows them to track their own health, in terms of appointments, results, medications …would be …great.” (G6). Limited resourcing, time availability and dispersed location of consumers were described as barriers to the access and use of technological infrastructure needed to enable consumer-centred care.

Governance and management were considered vital as rural sites transitioned from paper to digital. Adequate resourcing and support for staff through this transition was important: “In …the last five years, we’ve introduced them (staff) to [the electronic medical record] and that has been a huge challenge with a lot of change initiatives and management to …bring them along on the journey.” (E2). Participants identified that governance and management efforts should be targeted at providing effective data governance, protocols for sharing data with external providers, and reducing unsafe workarounds.

In the IT capability dimension, digital infrastructure was limited by internet connectivity: “The other barrier …is our connectivity within our sites, with being rural and remote. We don’t always have the greatest internet. …Our bandwidth and our speed [is poor]” (F8). During transition phases, participants reported the ‘hybrid’ paper-digital model resulted in duplicated information and poor data accuracy. The use of dashboards was valuable for visualising data.

In the people, skills and behaviour dimension, the digital literacy of the healthcare workforce mediates their acceptance of digital health: “The hardest thing was they’re extremely experienced and knowledgeable clinicians, and they’ve had to now go into something where they feel inadequate and feel that they can’t do their job” (E1). Participants indicated that the continued use of telehealth and investment in education to enhance individual competence and clinician confidence in digital technologies can minimise unnecessary workarounds and contribute to providing equitable care to rural populations.

Interoperable systems were perceived to facilitate efficient and accurate exchange of clinical information. Continuity of care is difficult between primary care providers, state-funded health services, and external providers in rural settings: “I can see a benefit in patient care delivery for when the entire health service is on the same system, because it will help with the transfer of the patient care through the different journeys” (B4). Participants emphasised that poor information visibility with external providers limited external interoperability, and the numerous systems utilised within a healthcare system limited internal interoperability.

The strategic focus of rural healthcare systems is interoperability, digital competency and investment in education and training. Strategic adaptability and alignment to organisational strategies is reported as challenging in rural contexts as digital health solutions were originally tailored for other healthcare systems in Queensland: “The state-wide solutions don’t really cater for the [rural health], because of how isolated and remote it is” (J10).

Rural healthcare providers use data analytics for healthcare performance tracking. Accurate data input by clinicians was critical for data analytics: “[The digital system] is our source of truth and it needs to be correct and up to date because that’s where all of our information from a funding perspective comes from” (B3). The continued use of paper is required for manual auditing. Participants saw value in extending data analytics to provide insight into trends and identify clinical risks, particularly for chronic disease management.

Relationships among digital health capability dimensions and outcomes

All four healthcare outcomes (population health, patient experience, provider experience, and healthcare costs) were described to be influenced by the digital health capability dimensions (Fig. 3; Table 2, Appendix 4). Strategy did not directly impact any outcome.

Relationships among the digital health capability dimensions

Interrelationships were present among all digital health capability dimensions (Fig. 4, Appendix 5).

Participants described the strategy dimension influenced the governance and management, people skills and behaviour, IT capability, interoperability and consumer-centred care dimensions. To incorporate digital transformation in the strategy and facilitate “care closer to the home” (J4), monetary and human resources are required. Enacting the digital strategy requires balancing priorities to develop the digital capability of the health system and “invest in the education and training of staff” (F7) to improve people, skills, and behaviour. Investment in technology infrastructure is required: “to invest in any further digital transformation, [it] must come with updated hardware infrastructure” (F6). Interoperability was core to the strategy, with the vision to “have one system, …so …all of our users …are only seeing one system, and if that’s not possible, then get interoperability front and centre on everyone’s roadmap” (G2).

Participants reported the challenge of governance and management and described its influence on all dimensions. Resource constraints and a lack of digital health governance within individual healthcare systems have hampered the digital health strategy from being realised. Implementation of technologies (e.g., telehealth) and structures (“consumer and community engagement team” (I6)) to facilitate consumer-centred care have been introduced in rural settings. Due to the segmentation of healthcare systems and primary and secondary care, participants expressed the importance of interoperability standards: “blanket rules that all digital platforms …talk(ed) to each other” (B6). In some instances, efforts to improve interoperability have been introduced by management, ensuring that the same system is used across sites: “Patient flow manager for us is our communication tool and we made sure that every site has [it]” (D12). Despite “government documents that dictate how it should be used, …they’re not well enforced” (F8) and individual variations exist in technology use. Establishing a “culture …[that] supports very open and transparent reporting of incidents” (A7) and structures such as a “business analysis and decision support team …[and] a nurse informatics [area]” (B10) facilitated data analytics.

IT capability influenced the governance and management, data analytics, consumer-centred care, people, skills, and behaviour, and interoperability dimensions. Governance and management were facilitated by providing “a full audit system …we can audit, we can review, we can look at gaps” (F8). IT also enabled analytics: “we use [software] to collate and to present data back to clinical teams, …for decision making, …to understand trends, …[and] for reporting …to the board and executive” (I6). Leveraging the capability of web-based portals, community healthcare directories, and telehealth have “enabled deeper engagement with the community” (F9) facilitating consumer-centred care. In some instances, IT improved interoperability: “we can see every admission to a public hospital in Queensland, and clinical notes, and discharge summaries” (B2). However, other IT did not meet interoperability standards and, the inclusion of additional IT was sometimes met with fear and frustration.

Interoperability influenced the governance and management, data analytics, people skills and behaviour, and IT capability dimensions. Participants expressed frustration with the limited interoperability: “instead of having one single channel which is commonly shared by everybody, we now have five different variants at both ends” (A3). Suboptimal interoperability impedes IT capability and data analytics: “if everything is linked to all databases, …you [would] have these wonderful capabilities to put your parameters in and run a report” (D9). Participants noted that a lack of interoperability between state-wide systems is “fraught with risk” (C9) that need to be managed.

Participants described how data analytics influenced the strategy, governance and management, and people, skills, and behaviour dimensions. Reporting and visualisation of data facilitated “operational and strategic planning” (J8). Data analytics can be used to actively monitor whether national standards are met: “We have a national standard called Emergency Length of Stay – …making sure patients leave within four hours. …I use the [digital] system …to keep tracking ‘where are we at? What’s our timing, what are we doing’” (E1). However, individuals had a “sense that the data will be used against people” (D6) and expressed concerns “over being a micro-manager” (D4).

The consumer-centred care dimension did not influence any digital health capability dimensions.

People skills and behaviour appeared to influence the data analytics and consumer-centred care dimensions. Healthcare professionals perform workarounds to overcome system limitations, often resulting in poor data quality hampering data analytics: “garbage in, garbage out. …Because people didn’t enter information correctly, it … threw out the whole dataset.” (E9). Digital health literacy of healthcare professionals and consumers influenced the delivery of consumer-centred care: “To access healthcare moving forward you will have to have a level of digital acuity and we need to be responsible for building competency and checking for competency. …It’s not just for the patients, …it’s a skill that we need to embed with our staff.” [B7].

Discussion

Despite the potentially transformative role of digital health to address access and equity [16], healthcare systems can struggle with implementing digital health in a way that addresses the health needs of marginalised communities. The key challenges across the seven capability dimensions involved enhancing workforce education and support, increasing IT capability, enabling interoperability, and catering healthcare delivery to rural settings. The existing digital health capability framework was improved by adding the sub-dimensions of resourcing, fit-for-purpose, and attitude, which are essential for rural digital transformation. The extensive use of telehealth and clinical dashboards are exemplar technological implementations enhancing rural digital health capability.

Our study in rural and remote Australia adds critical insight into the interrelationships among dimensions of digital health capability, confirming the need for rigorous strategy, governance, optimised digital technologies and a capable workforce to drive digital transformation. Second, it links the capability dimensions with outcomes reporting how healthcare outcomes in the rural setting are directly influenced by six of seven digital health capability dimensions. Third, it extends knowledge on the critical role of digital health in healthcare settings where need is high but appropriate, sustainable adoption is challenging.

Implications for practice

Healthcare leaders need to coordinate improvement efforts targeted across the dimensions of digital health. First, rural healthcare systems require a robust digital health strategy. The strategy dimension did not appear to influence outcomes directly, rather, the strategy dimension influenced other dimensions which then influenced outcomes. To deliver on the digital strategy, governance and management frameworks need to be established to support the provisioning of technical elements and development of workforce capability and consumer digital literacy. To ensure local needs are met, digital capability building initiatives require a clear local digital strategy, critical for coordinating activities [19], setting clear targets towards the desired future state [28], and motivating stakeholders towards pursuit of the quadruple aims of healthcare [19]. A concurrent state-wide study of digital health capability in Queensland identified the need for strategic initiatives to address variations in capability in rural healthcare systems [29, 30]. A metropolitan-originated digital health strategy is unlikely to address rural healthcare delivery challenges.

Data analytics capability can be optimised in rural settings to support decision-making and strategic development. We evidenced that data analytics can influence strategy and has a bidirectional relationship with the governance and management and people, skills and behaviour dimensions. Foundationally, data analytics capability is influenced by the interoperability and IT capability dimensions. This indicates that improving interoperability and IT capability to enhance information exchange and the usability of data can strengthen the data analytics capability, resulting in better informed and executed strategy supported by governance and management. In settings challenged with health inequities and coverage of essential healthcare [1], investing in data analytics capability will build a foundation for predictive and prescriptive analytics to benefit individual and population health [31, 32]. Clinical insights gained from data analytics can direct strategic priorities of rural healthcare delivery. We found that rural healthcare workers are seeing these early benefits through identification of clinical risk, particularly in chronic disease management and for early intervention.

Our findings demonstrate that participants view consumer-centred care as a capability that is shaped by other dimensions rather than informing other dimensions. Existing literature has struggled to articulate the intersection between consumers and digital health in system wide transformation. A systematic review of digital health capability revealed less than 10% of studies examined consumer-centred care [17]. The importance of the consumer-centred care dimension was evident in participants perceptions that it improved population health and patient experience. Emerging insights from broader literature indicate the need to consider additional consumer digital health themes (e.g., ethical implications, choice, transparency) [33,34,35]. Defining best practice processes (e.g., consumer panels, committees) and people (e.g., diversity, inclusion) to integrate consumer perspectives into digital initiatives remains necessary to rural healthcare improvement to address access and equity challenges.

Limitations

The qualitative methodology is limited to inferring association among the capability dimensions and outcomes, rather than attributing causality. Perceptions of digital health capability were captured from the purposive sample of interviewed participants with diverse roles in the health service. Differences in perspectives across different participant cohorts were not examined. We are unable to account for the confounders to perceived digital capability and outcomes which is likely to be influenced by the experience of participants in their work setting, at the time of data collection.

Conclusions

Digital health holds the promise of overcoming the “tyranny of distance”. Improvement of essential health services in rural settings is critical to health and wellbeing of populations experiencing health inequities. Using a multi-site case study analysis of rural healthcare systems, this study evidenced the complex interplay among the dimensions of digital health capability and the association between the dimensions and healthcare outcomes. The drivers of digitally enabled healthcare improvement in rural settings transcend single dimensions of digital health capability. A focus on digital strategy is foundational to enabling improvements across technical and human capabilities. Better leveraging data analytics and embedding consumer-centred care are likely to enable digital health improvements that meet local needs, enhancing the patient experience, improving population health, reducing the cost of care, and improving the provider experience. Improving care for our rural populations is critical to entire system improvement.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available in accordance with the approved Human Research Ethics Application and institutional requirements. For enquiries about the availability of data and materials contact the corresponding author at lee.woods@uq.edu.au.

Abbreviations

- IT:

-

Information technology

References

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages: United Nations; 2023 [cited 2023 29 September 2023]. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3

eHealth Queensland. Digital strategy for rural and remote healthcare. Queensland: State of Queensland (Queensland Health); 2021.

Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2020 Summary Report. AIHW Canberra, Australia; 2020.

Queensland Department of Health. Rural and remote health and wellbeing strategy 2022–2027. Queensland: State of Queensland (Queensland Health); 2022.

Marshall A, Babacan H, Dale AP. Leveraging digital development in regional and rural Queensland: Policy Discussion Paper. 2021.

Queensland Health. Digital health 2031: a digital vision for Queensland’s health system. Brisbane, Queensland: State of Queensland; 2022.

Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals Family Med. 2014;12(6):573–6.

Woods L, Eden R, Canfell OJ et al. Show me the money: how do we justify spending health care dollars on digital health? Med J Aust. 2022.

Yao R, Zhang W, Evans R, et al. Inequities in health care services caused by the adoption of digital health technologies: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(3):e34144.

Esteban-Navarro M-Á, García-Madurga M-Á, Morte-Nadal T, et al. The rural digital divide in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe—recommendations from a scoping review. Informatics. 2020;7(4):54.

Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Blumberg HM, et al. The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: a systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4(1):125.

Clarke MA, Skinner A, McClay J et al. Rural health information technology and informatics workforce assessment: a pilot study. Health Technol. 2023:1–9.

Curioso WH. Building capacity and training for digital health: challenges and opportunities in Latin America. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(12):e16513.

Clark CR, Akdas Y, Wilkins CH, et al. TechQuity is an imperative for health and technology business: Let’s work together to achieve it. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(9):2013–6.

World Health Organization. WHO Guideline on Health Workforce Development, Attraction, Recruitment and Retention in Rural and Remote Areas. 2021.

World Health Organization. Recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. World Health Organ. 2019:2020–10.

Duncan R, Eden R, Woods L, et al. Synthesizing dimensions of Digital Maturity in hospitals: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(3):e32994.

Woods LS, Eden R, Duncan R et al. Which one? A suggested approach for evaluating digital health maturity models. Front Digit Health. 2022.

Cresswell K, Sheikh A, Krasuska M, et al. Reconceptualising the digital maturity of health systems. Lancet Digit Health. 2019;1(5):e200–1.

World Health Organization. Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. p. 60.

Martin G, Clarke J, Liew F, et al. Evaluating the impact of organisational digital maturity on clinical outcomes in secondary care in England. NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2(1):1–7.

Flott K, Callahan R, Darzi A, et al. A patient-centered Framework for Evaluating Digital Maturity of Health Services: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(4):e75.

Queensland Health. Rural regions and locations Queensland1996-2023 [cited 2023 18 September]. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/employment/what-its-like-to-work-for-us/rural-remote/rural-regions-and-locations

Australian Government Department of Health. Health Workforce Locator Australia(no date) [ https://www.health.gov.au/resources/apps-and-tools/health-workforce-locator/health-workforce-locator

Yin RK. Qualitative research from start to finish. Guilford; 2015.

Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers: sage; 2021.

Avdagovska M, Menon D, Stafinski T. Capturing the impact of patient portals based on the Quadruple Aim and benefits evaluation frameworks: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e24568.

Burmann A, Meister S, editors. Practical application of Maturity models in Healthcare: findings from multiple digitalization Case studies. HEALTHINF; 2021.

Woods L, Eden R, Pearce A, et al. Evaluating Digital Health Capability at Scale Using the Digital Health Indicator. Appl Clin Inf. 2022;13(05):991–1001.

Woods L, Dendere R, Eden R, et al. Perceived Impact of Digital Health Maturity on Patient Experience, Population Health, Health Care costs, and Provider Experience: mixed methods Case Study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e45868.

Sanchez P, Voisey JP, Xia T, et al. Causal machine learning for healthcare and precision medicine. Royal Soc Open Sci. 2022;9(8):220638.

Almond H, Mather C. Digital Health: A Transformative Approach. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2023.

Kukafka R. Digital health consumers on the road to the future. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(11):e16359.

Health Consumers Queensland. Queensland Digital Health Consumer Charter. Queensland: Health Consumers Queensland; 2021.

Viitanen J, Valkonen P, Savolainen K, et al. Patient experience from an eHealth perspective: a scoping review of approaches and recent trends. Yearb Med Inform. 2022;31(01):136–45.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their appreciation to the many Queensland Health staff members who participated in this research.

Funding

This research was supported by the Digital Health CRC Limited (“DHCRC”) and Queensland Department of Health. DHCRC is funded under the Australian Commonwealth’s Cooperative Research Centres (CRC) Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LW, RE and CS devised the project with strategic direction from HM and RaD. LW, RE and RhD contributed to data collection under the supervision of CS. SM and JK contributed to data analysis and reporting of results with the assistance of LW, RE and CS. LW and RE wrote the manuscript with assistance from SM, JK, ReD, HM, RhD and CS. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received a multisite ethics approval from the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital [ID: HREC/2020/QRBW/66895], followed by site-specific research governance approvals. Informed, written content was provided by participants prior to data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Author Clair Sullivan is an editorial board member of BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Woods, L., Eden, R., Macklin, S. et al. Strengthening rural healthcare outcomes through digital health: qualitative multi-site case study. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 1096 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11402-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11402-4