Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers face the stigmatization of those caring for COVID-19 patients, creating a significant social problem. Therefore, this study investigated the stigmatization of healthcare workers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

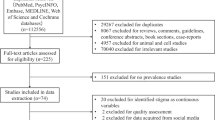

In this scoping review study, searches were conducted from December 2019 to August 2023 in Persian and English using various databases and search engines including PubMed (Medline), Embase, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, ProQuest, Science Direct, Springer, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and national databases. The study used English keywords such as Social Stigma, Health Personnel, Healthcare Worker, Medical Staff, Medical Personal, Physicians, doctors, Nurses, nursing staff, COVID-19, and coronavirus disease 2019, and their Persian equivalents, and their Persian equivalents to explore healthcare workers’ experiences of COVID-19-related stigma.

Results

From a total of 12,200 search results, 77 eligible studies were included in this study. stigmatization of healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients was evident from the literature because of fear, misinformation, and negative self-image. Manifestations were violence and deprivation of social rights, resulting in adverse biopsychosocial, occupational, and economic consequences. This condition can affect negatively health staff themselves, their families, and society as well. Anti-stigmatization measures include informing society about the realities faced by healthcare workers, presenting an accurate and empathetic image of health workers, providing psychosocial support to health workers, and encouraging them to turn to spirituality as a coping mechanism. There are notable research gaps in comprehending the phenomenon, exploring its variations across diverse healthcare roles and cultural contexts, examining its long-term effects, and monitoring shifts in stigma perceptions over time.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the stigmatization of healthcare workers, causing mistreatment and rights violations. This stigma persists even post-pandemic, posing a psychological dilemma for caregivers. Addressing this requires comprehensive strategies, including tailored stigma prevention programs and research to understand its psychological impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic, recognized as a global traumatic event, has profoundly disrupted various aspects of daily life worldwide [1] and has put unprecedented and significant pressure on the healthcare system and its healthcare workers (HCWs) [2]. Despite the important role of HCWs in the fight against infectious diseases [3], this pandemic has brought hard times for them worldwide. Being on the frontline of fighting this pandemic has had many direct and indirect negative effects on them, from physical and psychological injuries to professional and social issues [4]. So much so that these conditions began to be seen as a social problem [5]. One challenge faced when working with COVID-19 patients is the stigma HCWs may encounter due to being seen as a serious threat, posing a significant hurdle in the healthcare field [6]. In health, stigma refers to the labeling and discrimination of people based on a particular disease [7]. According to the WHO [8], social stigma in healthcare is a negative association between a group of people and a particular disease [8]. Even people who do not suffer from this disease but have other common characteristics, such as family members or HCWs responsible for their care, can suffer from this stigma [9]. Stigmatization is the main cause of discrimination and disadvantage, leading to a violation of human rights [10]. The stigma associated with COVID-19 had consequences such as increased fatigue, burnout, and lower satisfaction, which affected the well-being of HCWs [11]. In addition, perceived stigma impaired feelings of self-efficacy and increased psychological and psychophysical problems [12]. According to the available literature, stigma is a complex phenomenon that is experienced differently depending on the type of illness and the social conditions of those affected [13]. On the other hand, the effects and consequences of stigma experienced by stigmatized people can persist in the long term, even after the end of quarantine and the containment of the epidemic [11].

The history of previous epidemics, including SARS and MERS, has shown that HCWs were usually considered carriers of the virus and were transmitted by others because of this status [14, 15]. This situation not only had a negative impact on their mental health [16,17,18], but also affected their desire to remain in the profession [19]. Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, some studies, including systematic reviews, have addressed the stigmatization of HCWs [4, 20]. However, due to the ongoing pandemic, a re-examination of changes in healthcare professionals’ experiences of stigmatization and its impact on their personal and professional lives is needed [21, 22]. Conducting review studies makes the role of stigma in changing work relationships, mental health, and professional experiences clearer and offers effective solutions to support health professionals in critical situations [22,23,24]. In addition to providing a deeper understanding of the factors that influence stigma, its manifestations, and its social, psychological, and occupational effects, this review study aims to fill the gap by providing updated insights and further clarifying the role of stigma in altering work relationships, mental health, and professional experiences and offers individual and organizational strategies to address these issues and support HCWs.

Method

Study plan

This review used Arksey and O’Malley’s [25] six-level framework to review comprehensive texts [25]. To examine the number, scope and nature of available studies on stigma related to COVID-19 in HCWs. The results are reported according to the guidelines of the PRISMA Extended Program for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) [26]. This approach consists of six steps: 1) defining the research question, 2) identifying related studies, 3) criteria for selecting studies, 4) capturing and classifying key findings (e.g. study location, intervention, comparison, study population, study objectives, outcomes, measures and conclusions, etc.), 5) summarizing and reporting results, and 6) consulting stakeholders (optional). The purpose of a scoping review is a detailed examination of the texts in a specific area without assessing the quality of the studies. Therefore, qualitative assessments are often not performed and studies are not critiqued [25]. Therefore, no qualitative assessment of the articles was performed in the present study. Each of the steps carried out in this study is explained below.

Determining the research question

The present scoping review was guided by the following questions: a) Has the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a recognizable manifestation of stigmatization of HCWs? b) What symptomatic consequences have been observed in HCWs as a result of COVID-19-related stigmatization? c) What are the tangible and intangible effects of COVID-19-related stigma on HCWs? d) What proactive measures could be taken to reduce the incidence and impact of COVID-19-related stigma among HCWs? e) What research gaps exist in the study of COVID-19-related stigma among HCWs that require further investigation?

Identification of related studies

The studies utilized in this research were sourced from a comprehensive search across various databases and search engines, including PubMed (Medline), Embase, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, ProQuest, Science Direct, Springer, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and National databases. This extensive search strategy involved English keywords such as Social Stigma, Health Personnel, Healthcare Worker, Medical Staff, Medical Personal, Physicians, doctors, Nurses, nursing staff, COVID-19, and coronavirus disease 2019, and their Persian equivalents, combined using Boolean operators AND, OR, * to ensure inclusivity and exhaustiveness.

One example of the search strategy using MeSH terms in PubMed is listed in Table 1.

Study selection criteria

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied in the review of titles/abstracts and full text to determine the final number of studies:

-

All English and Persian studies with available full texts published between December 2019 and August 2023 related to the stigmatization of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

HCWs including nurses, doctors, healthcare professionals, paramedics, and technicians.

-

Studies relating to previous epidemics were excluded.

After a comprehensive search, the studies were reviewed and selected in a two-stage process. The studies were screened by two researchers (M. Sh. and L. Z.). In the first stage, the titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by two researchers to determine the eligibility of the studies. The studies were classified as relevant, possibly relevant, or not relevant. In the second stage, the potentially relevant studies were reviewed independently by the researchers to determine final eligibility. Research results were then compared and duplicates were removed using EndNote-X9 software. Researchers were present at both stages of the meeting to share opinions and reach consensus, and a third party (R.N.) was consulted when necessary. The sources of all studies eligible for further review that were not provided in the electronic database search, the review, and the search strategy were documented and stored in each database, and the search results were stored in the EndNote-X9 resource management tool. The PRISMA-ScR diagram shows the process of searching and selecting texts.

Registration and classification of key results

After selecting the texts, the data were extracted and recorded in tables in Microsoft Word 2023. The main areas of focus in the data included authors, date of publication, country, type of texts, sample characteristics, and key findings (Table 2).

Results

At this stage, the results are summarized and reported to answer the research questions. Of the 77 studies reviewed for the final analysis, 76 were articles and one was a thesis. The design of the studies was as follows: 37 quantitative studies (34 cross-sectional studies and three surveys), 11 qualitative studies, two mixed-method studies, and 12 reviews (one scoping review, three narratives, one umbrella, four systematic studies, one meta-analysis, and one synthesis), three reports, five opinion pieces, seven letters to the editor, and one secondary analysis. Five studies are multi-country, three from Egypt, three from South Korea, seven from India, two from Iran, two from Nigeria, four from the United States, two from Italy, one from Australia, one from Nepal, one from Jordan, two from Saudi Arabia, one from Greece, one from Jakarta, one from Pakistan, two from Ghana, one from Canada, two from Indonesia, one from Sri Lanka, one from Tanzania, three from Turkey, one from Africa, one from Peru, two from Taiwan, and one from Kosovo (Table 2). According to the study results, the reasons for the stigma associated with COVID-19 can vary greatly from fear of the COVID-19 virus [27,28,29,30,31], infecting family members, feeling dirty and negative self-image [32,33,34] to limited knowledge about the virus [28, 29].

Manifestation of stigmatization of HCWs

In most of the studies reviewed, HCWs, particularly those directly serving patients, have faced significant stigmatization amid the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). This stigmatization encompasses various forms of mistreatment, including bullying, verbal abuse such as ridicule and insults in public settings, physical assaults like spraying bleach or throwing objects, and even attacks on ambulances [35,36,37,38]. Additionally, HCWs have encountered harassment and violations of their social and civil rights, such as being denied access to public transportation, rental housing eviction, and denial of services [37, 39,40,41,42,43]. Moreover, they have experienced ingratitude from colleagues, family members, the public, and neighbors [27, 29, 33, 36, 39, 40, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Self-stigmatization has also been reported, along with strains in relationships with friends and negative portrayals in the media [29, 33, 38, 40, 47, 48, 52, 58, 60,61,62,63]. In general, given the conditions and risks associated with COVID-19, stigmatization has become a widespread and serious phenomenon that requires programs and solutions to improve the health level of society by protecting workers.

Consequences related to stigma experienced by HCWs can be as follows

Psychological consequences: These people may suffer from stress, anxiety [20, 27, 32, 39, 41, 42, 47, 62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69], grief, depression [32, 50, 54, 60,61,62, 66,67,68, 70,71,72,73], and suicidal thoughts [54]. Sadness, grief, feelings of guilt [33, 60, 63], hiding the positive result of the COVID-19 test [63], anger, and rage [58, 62], inability to make decisions and not seeking psychotherapy [33, 52, 56], mental health disorders, long-term psychosocial consequences, PTSD symptoms [68, 74] and fear of virus transmission [6, 75, 76] were also among the psychological consequences.

Physical consequences: Sleep disturbances, fatigue [11, 72, 74, 77], exhaustion [32] and a weak immune system [66].

Professional and social consequences: included compassion fatigue, job burnout [11, 74, 77,78,79], intention to give up work, social isolation [10, 33, 66, 79], loneliness, avoidance of family, humiliation, communication disorders [61], negative effects on work performance and resilience [39, 57, 80, 81], weakening of social cohesion, increase in rumors, loss of social status, deprivation of social and civil rights, such as deprivation of access to public services [39, 57, 80, 81], reduction in social value and social acceptance [6, 10, 36, 39, 41, 66, 82, 83], emotional deprivation [66, 82], a feeling of anxiety when traveling home from the hospital [84], a tendency to self-medicate and refusal to go to the hospital [37], concern about public opinion, concealment of work details [6, 32], and impact on crisis management [32, 41, 84]. It should be noted that one study mentioned that the stigmatization experienced did not affect work performance [85].

Economic consequences: Those affected suffered economic losses because they were expelled from their place of residence and had to give up their job [6, 32].

Tangible and intangible effects of COVID-19-related stigma on HCWs

The stigma linked to COVID-19 among HCWs has led to the development of negative beliefs, resulting in hesitancy to seek treatment. This reluctance can negatively impact the healthcare profession and society, as affected workers may avoid undergoing diagnostic tests or seeking necessary treatment [33, 37, 86]. Additionally, their families may also face shame and rejection [9, 87], potentially leading to passive acceptance of the stigma [88].

The unseen effects such as loss of societal trust and adverse effects on HCWs, can also result in significant economic losses for society [32, 89].

Proactive measures to reduce COVID-19-related stigma among HCWs

Considering the mentioned consequences of dealing with the stigmatization of HCWs in the era of COVID-19 and possible epidemics in the future, the solutions used by workers and the things suggested in some studies were psychosocial support from family, colleagues, officials and community [33, 38, 50, 52, 56, 57, 65, 71], providing financial rewards [33, 56], ensuring safety in the workplace, adequate training about COVID-19 for HCWs and better cooperation in the workplace [11, 30, 47, 77, 78], implementation of programs to reduce stigma, including increased public awareness of the nature of the disease, clear dissemination of information about the disease to the public, appropriate community education, public education about disease management, social care and empathy, appropriate representation of health care professionals and efforts to show staff commitment through the media, and clear public health policy announcements [11, 30, 31, 44, 56, 63, 90], appeal to spirituality [41, 60], adoption of measures to improve social motivation of HCWs by the Ministry of Education and Health [31, 56], strict implementation of preventive measures, peer support, proper adherence to personal protection protocol [66, 85, 91], transparency and accountability [44], provision of evidence-based measures to encourage society to reduce offending by workers [92] and lack of awareness of existing conditions by workers [93].

Research gaps in COVID-19-related stigma among HCWS

There are significant research gaps in understanding the stigma associated with COVID-19 among HCWs, necessitating further investigation to develop validated tools for assessing HCWs’ COVID-19-related stigma. Moreover, it is essential to explore the variations in stigma across different healthcare roles and conduct comprehensive research on the long-term impacts of stigma on HCWs. It is also crucial to examine how stigma manifests in diverse cultural and regional contexts. Additionally, longitudinal studies are vital to track changes in stigma perceptions over time.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the stigmatization of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigmatization of these workers was evident, leading to adverse consequences that affected healthcare staff, their families, and society. It is essential to consider anti-stigmatization measures. However, there are research gaps regarding COVID-19-related stigmatization of HCWs.

The review highlighted that HCWs globally faced significant stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic, manifesting in various forms such as bullying, verbal abuse, physical assaults, and denial of rights and services. This stigmatization also included self-stigmatization, strained relationships, and negative portrayals in the media. SARS pandemic studies supported these findings, emphasizing social stigma experienced by frontline HCWs [94]. Additional research indicated that HCWs encountered verbal and nonverbal violent behaviors aligned with social stigma expressions [95], possibly stemming from society’s aim to protect itself against the stigmatized situation.

Studies suggested that stigma was fueled by fears related to virus transmission and contracting COVID-19, similar to patterns observed during the Ebola epidemic [96]. Individuals might avoid stigmatized individuals due to perceived harm, potentially influenced by a lack of comprehensive understanding of the virus. HCWs themselves faced stigmatization, partly due to negative self-perception and feeling unclean, leading to self-stigmatization behaviors and isolation in society [97]. Their behavior may stem from a desire to avoid being perceived as outsiders, fostering an “us” versus “them” mentality and exacerbating feelings of isolation in society.

Contradictory findings from a census study [97] highlighted that stigmatization stemmed from viewing stigmatized individuals as unhelpful to society. However, the present study attributed stigmatization within society to a lack of knowledge about COVID-19, including transmission, quarantine, and contagiousness duration. Society’s fear and avoidance of HCWs might be rooted in limited understanding of the disease and the nature of the virus.

According to this study, HCWs experiencing stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic are more likely to develop negative beliefs and be reluctant to seek treatment, which has a detrimental impact on healthcare and societal trust. Families may also face shame, perpetuating stigma and causing economic losses. This study revealed instances of HCWs concealing their occupational identity, including hiding a positive COVID-19 test result, aligning with previous research indicating negative emotions as a consequence of stigmatization [95]. Such concealment likely stems from anticipating negative reactions due to previous experiences with societal interactions, family dynamics, or feelings of shame and social alienation.

This experience of stigma can lead to various consequences falling into four main categories: psychological, physical, occupational-social, and economic. Infectious diseases historically associated with stigma, such as plague, yellow fever, and influenza, have demonstrated how this social phenomenon is influenced not only by disease characteristics but also by social and organizational processes, resulting in discrimination, hostility, and social disharmony [74, 98, 99].

Stigma related to emerging infectious diseases can significantly affect the mental and emotional well-being of HCWs, potentially leading to long-term repercussions on their health and quality of life [70, 100, 101]. Stigmatization can result in discrimination-related stress, decreased self-esteem, reduced self-efficacy [101, 102], and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among affected individuals [68, 74]. Additionally, physical effects like sleep disturbances, fatigue, exhaustion, and compromised immune function have been observed in stigmatized HCWs. Addressing these challenges and providing support to HCWs during infectious disease outbreaks is crucial.

The stigma surrounding infectious diseases stems from a combination of disease characteristics, societal beliefs, and organizational responses. This stigma can cause significant harm to both individuals and communities that are stigmatized [103]. This phenomenon can result in various occupational-social consequences, such as compassion fatigue, job burnout, reduced satisfaction, desire to leave the profession, social isolation, loneliness, communication breakdowns, negative effects on work performance and resilience, a weakening of social cohesion, and economic losses [6, 32]. Other studies highlighted impacts on social cohesion, including increased rumors [39, 57, 80, 81], loss of social status, deprivation of social rights, concern about public attitudes [6, 10, 36, 39, 41, 66, 82, 83], concealment of work details, decreased social value and acceptance [6, 32], emotional deprivation, fear of returning home from the hospital, self-medication tendencies, reluctance to seek hospital care, crisis management challenges, economic withdrawal from work, and expulsion from residence [32, 41, 84]. Notably, one study found that stigma did not affect the work performance of HCWs [85], while the World Health Organization (WHO) underscores that stigma is a significant driver of discrimination, exclusion, and human rights violations [91].

Some studies have reported various interventions to reduce the negative impact of COVID-19-related stigmatization of HCWs. These measures include providing psychosocial and economic support services, creating better conditions in the work environment, fostering better cooperation, and providing adequate training to enhance safety and health. Additionally, raising public awareness, disseminating information about the disease, and offering appropriate training to address reactions are important steps in combating stigmatization. Due to stigmatization, the media plays a positive role in highlighting employee engagement, implementing measures to boost social motivation, raising awareness, and educating the public on disease management, care, and social empathy. It is also crucial to promote spirituality and adherence to personal protection protocols while maintaining transparency. These efforts align with WHO recommendations to combat stigma, which include disseminating facts, correcting misinformation, dealing with fake stories, and avoiding emphasizing negative aspects and threatening messages about COVID-19. Utilizing official and reliable sources such as the Ministry of Health, WHO, and UNICEF, and choosing words carefully when speaking are essential strategies in addressing stigmatization [91].

Considering that the most frequently experienced consequence of stigmatization is psychological problems, including stress, attention in this area is crucial. A review study [102] investigating the most effective stress reduction techniques for medical staff who come into contact with patients with severe coronaviruses (SARS, MERS, and COVID-19) emphasized that addressing employees’ psychological issues at an organizational level is vital. In addition to ensuring that interventions are appropriate, safe, and aligned with employees’ preferences, remote services such as recorded relaxation packages, recreational activities, and specific stress reduction techniques like mindfulness-based interventions, diaphragmatic breathing, and effective self-efficacy can be beneficial. As communicable diseases pose a constant threat to human society, it is essential to understand how disease-related stigma impacts the outcomes of disease control measures to develop more responsive public health policies during epidemic outbreaks in the future [90]. The results of the reviewed studies indicate that healthcare and nursing staff face a paradoxical and dual situation. While they are praised and applauded as health heroes from balconies [103], they are also avoided due to the perception of working in corona centers, creating a conflicting situation. The likelihood of problems arising in such a stressful environment is doubled.

Significant gaps in understanding the stigma associated with COVID-19 among HCWs are evident so far. These gaps include the need for validated tools to assess stigma and its long-term impacts, longitudinal studies to track changes in stigma perceptions over time, and exploring variations across different healthcare roles in diverse cultural and regional contexts.

Limitations

The review implemented a systematic and rigorous search strategy to fulfill its objective of consolidating the most recent scientific findings on COVID-19-related stigma among HCWs. It aimed not only to address the current circumstances but also to enhance comprehension of future challenges associated with stigma. However, it is essential to acknowledge the review’s scope limitation, as it solely included studies in English and Persian, potentially excluding relevant research in other languages. Additionally, the review considered both the advantages and drawbacks of Google Scholar as the primary search engine. While Google Scholar enables access to full texts and diverse sources, its dynamic search algorithms and limited journal indexing may pose limitations. To mitigate these constraints, the review diversified its search sources, incorporating other databases to ensure comprehensive coverage.

Suggestions for future research

Future research on COVID-19-related stigma among HCWs should focus on several key areas. Longitudinal studies are necessary to track the evolution of stigma over time and its lasting impact on HCWs post-pandemic, providing insights into how stigma changes and its long-term effects on mental health and job performance. Research should also explore how COVID-19-related stigma varies across different cultures and healthcare systems, allowing for the development of culturally sensitive interventions. It is crucial to develop and test the effectiveness of various interventions aimed at reducing stigma, including psychological support, educational programs, and policy changes. Further validation and refinement of stigma measurement tools, such as the COVID-19-related stigma scale for HCWs and the COVID-19 Stigma Scale are needed to ensure they are reliable and applicable in diverse contexts. Additionally, examining how stigma affects job performance, job satisfaction, and retention rates among HCWs can help healthcare organizations develop strategies to support their staff better. Finally, exploring the relationship between public perception of HCWs and the stigma they experience, including the influence of media portrayal and public discourse, can provide valuable insights into mitigating stigma.

Conclusion

The existing literature underscores the significant stigmatization experienced by healthcare professionals amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily stemming from societal fear and limited virus-related knowledge. This stigma often results in the mistreatment of HCWs and the infringement of their social rights, leading to profound psychological repercussions. The enduring impact of this stigma may persist even in the post-COVID era, creating a psychological dilemma for HCWs torn between their professional duties and societal attitudes. Addressing this issue necessitates a comprehensive understanding across various professional and social domains, alongside the formulation and refinement of strategies promoting community awareness, mutual understanding, and empathy. Past epidemic experiences underscore the inadequacy of interventions, warranting the development of more effective stigma prevention and management programs tailored to HCWs. Moreover, existing reviews have neglected the psychological aspects of stigmatization, highlighting the need for qualitative and systematic research to elucidate stigma’s conceptualization and its psychological implications. Through a combination of qualitative and quantitative studies, hypotheses regarding psychological issues related to stigma can be tested, paving the way for targeted interventions and improved strategies to mitigate the psychological impact of stigma.

Availability of data and materials

Data cannot be shared openly but are available on request from authors.

Abbreviations

- HCWs:

-

Healthcare Workers

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease of 2019

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

PRISMA Extended Program for Scoping Review

- SARS:

-

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

- PTSD:

-

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- UNICEF:

-

The United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund

- MERS:

-

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome

References

Jernigan DB. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Update: Public Health Response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak - United States, February 24, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(8):216–9. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6908e1.

Palese A, Papastavrou E, Sermeus W. Challenges and opportunities in health care and nursing management research in times of COVID-19 outbreak. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(6):1351–5.

Fernandez R, Lord H, Halcomb E, Moxham L, Middleton R, Alananzeh I, Ellwood L. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;111:103637-.

Schubert M, Ludwig J, Freiberg A, Hahne TM, Romero Starke K, Girbig M, et al. Stigmatization from Work-Related COVID-19 Exposure: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126183.

Dolić M, Antičević V, Dolić K, Pogorelić Z. Questionnaire for Assessing Social Contacts of Nurses Who Worked with Coronavirus Patients during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(8):930. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9080930.

Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):782.

Sheehan L, Corrigan P. Stigma of disease and its impact on health. The Wiley encyclopedia of health psychology. 2020:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119057840.ch139.

WHO. Social stigma associated with COVID-19 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/social-stigma-associated-with-covid-19.

Ransing R, Ramalho R, de Filippis R, Ojeahere MI, Karaliuniene R, Orsolini L, et al. Infectious disease outbreak related stigma and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: Drivers, facilitators, manifestations, and outcomes across the world. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:555.

Grover S, Singh P, Sahoo S, Mehra A. Stigma related to COVID-19 infection: are the health care workers stigmatizing their own colleagues? Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102381.

Ramaci T, Barattucci M, Ledda C, Rapisarda V. Social stigma during COVID-19 and its impact on HCWs outcomes. Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3834.

Do Duy C, Nong VM, Van Ngo A, Doan Thu T, Do Thu N, Nguyen QT. COVID-19-related stigma and its association with mental health of health-care workers after quarantine in Vietnam. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(10):566–8.

Butt G. Stigma in the context of hepatitis C: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(6):712–24.

Craddock S. Sewers and scapegoats: Spatial metaphors of smallpox in nineteenth century San Francisco. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(7):957–68.

Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510–2.

Gunawan J, Juthamanee S, Aungsuroch Y. Current mental health issues in the era of Covid-19. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102103.

Gunawan J, Aungsuroch Y, Marzilli C, Fisher ML, Nazliansyah, Sukarna A. A phenomenological study of the lived experience of nurses in the battle of COVID-19. Nurs Outlook. 2021;69(4):652–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.020.

Cengiz Z, Isik K, Gurdap Z, Yayan EH. Behaviours and experiences of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey: a mixed methods study. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(7):2002–13.

Li TM, Pien LC, Kao CC, Kubo T, Cheng WJ. Effects of work conditions and organisational strategies on nurses’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(1):71–8.

Handayani RT, Kuntari S, Darmayanti AT, Widiyanto A, Atmojo JT. Factors causing stress in health and community when the Covid-19 pandemic. J Keperawatan Jiwa. 2020;8(3):353–60.

Arias-Ulloa CA, Gómez-Salgado J, Escobar-Segovia K, García-Iglesias JJ, Fagundo-Rivera J, Ruiz-Frutos C. Psychological distress in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Safety Res. 2023;87:297–312.

Cheung T, Cheng CPW, Fong TKH, Sharew NT, Anders RL, Xiang YT, Lam SC. Psychological impact on healthcare workers, general population and affected individuals of SARS and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1004558.

Härkänen M, Pineda AL, Tella S, Mahat S, Panella M, Ratti M, et al. The impact of emotional support on healthcare workers and students coping with COVID-19, and other SARS-CoV pandemics – a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):751.

Sun P, Wang M, Song T, Wu Y, Luo J, Chen L, Yan L. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:626547.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Gratton JM. Understanding the Experiences of Frontline Workers in Long-Term Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Study (Master's thesis, Queen's University (Canada)).2022. 29421663.

Assefa N, Soura A, Hemler EC, Korte ML, Wang D, Abdullahi YY, et al. COVID-19 knowledge, perception, preventive measures, stigma, and mental health among healthcare workers in three sub-Saharan African countries: a phone survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;105(2):342.

Kwaghe AV, Ilesanmi OS, Amede PO, Okediran JO, Utulu R, Balogun MS. Stigmatization, psychological and emotional trauma among frontline health care workers treated for COVID-19 in Lagos State, Nigeria: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):855.

Nashwan AJ, Valdez GFD, Al-Fayyadh S, Al-Najjar H, Elamir H, Barakat M, et al. Stigma towards health care providers taking care of COVID-19 patients: a multi-country study. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):e09300.

Abdel Wahed WY, Hefzy EM, Ahmed MI, Hamed NS. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and perception of health care workers regarding COVID-19, a cross-sectional study from Egypt. J Community Health. 2020;45(6):1242–51.

Muhidin S, Vizheh M, Moghadam ZB. Anticipating COVID-19-related stigma in survivors and health-care workers: Lessons from previous infectious diseases outbreaks - An integrative literature review. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(11):617–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13140.

Zolnikov TR, Furio F. Stigma on first responders during COVID-19. Stigma and Health. 2020;5(4):375.

Saptarini I, Novianti N, Rizkianti A, Maisya Iram B, Suparmi S, Veridona G, et al. Stigma during COVID-19 pandemic among healthcare workers in greater Jakarta metropolitan area: A cross-sectional online study. Health Sci. J. Indones. 2021:12(1):6–13. https://doi.org/10.22435/hsji.v12i1.4754.

Turki M, Ouali R, Ellouze S, Ben Ayed H, Charfi R, Feki H, et al. Perceived stigma among Tunisian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. L’Encéphale. 2023;49(6):582–8.

Sachdeva A, Nandini H, Kumar V, Chawla RK, Chopra K. From stress to stigma–mental health considerations of health care workers involved in COVID19 management. Indian J Tuberc. 2022;69(4):590–5.

Aitafo JE, Wonodi W, Briggs DC, West BA. Self-medication among health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in southern Nigeria: knowledge, patterns, practice, and associated factors. Int J Health Sci Res. 2022;12:1–14.

Timothy DD, Lisette A, Shazia S, Monica B, Saloni S, Tiffany P, Eva P. Risk of COVID-19-related bullying, harassment and stigma among healthcare workers: an analytical cross-sectional global study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e046620.

Taylor S, Landry CA, Rachor GS, Paluszek MM, Asmundson GJG. Fear and avoidance of healthcare workers: an important, under-recognized form of stigmatization during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;75:102289.

Singh R, Subedi M. COVID-19 and stigma: Social discrimination towards frontline healthcare providers and COVID-19 recovered patients in Nepal. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102222.

Uvais NA, Aziz F, Hafeeq B. COVID-19-related stigma and perceived stress among dialysis staff. J Nephrol. 2020;33(6):1121–2.

Fan J, Senthanar S, Macpherson RA, Sharpe K, Peters CE, Koehoorn M, McLeod CB. An umbrella review of the work and health impacts of working in an epidemic/pandemic environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):6828.

Roelen K, Ackley C, Boyce P, Farina N, Ripoll S. COVID-19 in LMICs: the need to place stigma front and centre to its response. Eur J Dev Res. 2020;32:1592–612.

Argyriadis A, Patelarou A, Kitsona V, Trivli A, Patelarou E, Argyriadi A. Social discrimination and stigma on the community of health professionals during the Covid-19 pandemic. An ethnographic approach. MedRxiv. 2021:29:2021–10. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.28.21265608.

Khalid MF, Alam M, Rehman F, Sarfaraz R. Stigmatization of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Age. 2021;18(29):100.

Logie CH, Turan JM. How do we balance tensions between COVID-19 public health responses and stigma mitigation? Learning from HIV research. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2003–6.

Wickramasinghe E, de Zoysa P, Alagiyawanna A, Karunathilake K, Ellawela Y, Samaratunga I, et al. The experience of stigma by service personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka J Psychiatry. 2021;12(2):15. https://doi.org/10.4038/sljpsyc.v12i2.8289.

Abuhammad S, Alzoubi KH, Al-Azzam S, Alshogran OY, Ikhrewish RE, Amer ZaWB, Suliman MM. Stigma toward healthcare providers from patients during COVID-19 era in Jordan. Public Health Nurs. 2022;39(5):926–32.

Adhikari SP, Rawal N, Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Banmala S, Awal S, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and perceived stigma in healthcare workers in Nepal during later phase of first wave of COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Cureus. 2021;13(6):e16037.

Alajmi AF, Al-Olimat HS, Abu Ghaboush R, Al Buniaian NA. Social avoidance and stigma among healthcare workers serving COVID-19 patients in Saudi Arabia. SAGE Open. 2022;12(2):21582440221095844.

Trusty WT, Swift JK, Higgins HJ. Stigma and Intentions to Seek Psychotherapy Among Primary Care Providers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mediational Analysis. Int J Behav Med. 2023;30(4):572–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-022-10119-0.

Gualano MR, Sinigaglia T, Lo Moro G, Rousset S, Cremona A, Bert F, Siliquini R. The burden of burnout among healthcare professionals of intensive care units and emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):8172.

Makino M, Kanie A, Nakajima A, Takebayashi Y. Mental health crisis of Japanese health care workers under COVID-19. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020;12(S1):S136.

Maren J, Marianna T, Elena J-P, Galateja J, Ruth K. Occupational challenges of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e054516.

Simeone S, Rea T, Guillari A, Vellone E, Alvaro R, Pucciarelli G. Nurses and Stigma at the Time of COVID-19: A Phenomenological Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;10(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010025.

Bagheri Sheykhangafshe F, Fathi-Ashtiani A. Psychosocial consequences of the post-coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): systematic review study. J Appl Psychol Res. 2022;13(3):53–72.

Belice T, Çiftçi D, Demir I, Yüksel A. COVID-19 and stigmatisation of healthcare providers. Eureka: Health Sciences,(6). 2020:3–7.2020:3–7. https://doi.org/10.21303/2504-5679.2020.001447, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3746838.

Chu E, Lee KM, Stotts R, Benjenk I, Ho G, Yamane D, et al. Hospital-based health care worker perceptions of personal risk related to COVID-19. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Suppl):S103–12.

Rahmani N, Nabavian M, Seyed Nematollah Roshan F, Seyed F, Firouzbakht M. Explaining nurses’experiences of social stigma caused by the Covid-19 pandemic: a phenomenological study. Nurs Midwifery J. 2022;20(7):538–48.

Bagheri SF, Sadeghi CE. Fear of medical staff: the importance of stigmatization during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2022.

Huarcaya-Victoria J, Podestá A. Factors associated with distress among medical staff of a general hospital during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru. 2020.

Mostafa A, Sabry W, Mostafa NS. COVID-19-related stigmatization among a sample of Egyptian healthcare workers. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0244172.

George CE, Inbaraj LR, Rajukutty S, de Witte LP. Challenges, experience and coping of health professionals in delivering healthcare in an urban slum in India during the first 40 days of COVID-19 crisis: a mixed method study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e042171.

Nyumirah S. Literature review: psychological impact on health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prosiding Kesehatan. 2021;1(1):20–7.

Jahangasht K. Social stigma: the social consequences of COVID-19. J Marine Med. 2020;2(1):59–60.

Han S, Choi S, Cho SH, Lee J, Yun J-Y. Associations between the working experiences at frontline of COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of Korean public health doctors. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):298.

Lu M-Y, Ahorsu DK, Kukreti S, Strong C, Lin Y-H, Kuo Y-J, et al. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, sleep problems, and psychological distress among COVID-19 frontline healthcare workers in Taiwan. Front Psych. 2021;12:705657.

Tirukkovalluri SS, Rangasamy P, Ravi VL, Julius A, Chatla C, Mahendiran BS, Manoharan A. Health care professional’s perceived stress levels and novel brief COPE-4 factor structure-based assessment of coping methods during COVID-19 pandemic in India: a multi-modal cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(7):3891.

Park C, Hwang J-M, Jo S, Bae SJ, Sakong J. COVID-19 outbreak and its association with healthcare workers’ emotional stress: a cross-sectional study. Jkms. 2020;35(41):e372–0.

Temsah M-H, Al-Sohime F, Alamro N, Al-Eyadhy A, Al-Hasan K, Jamal A, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(6):877–82.

Menon GR, Yadav J, Aggarwal S, Singh R, Kaur S, Chakma T, et al. Psychological distress and burnout among healthcare worker during COVID-19 pandemic in India—A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0264956.

Shiu C, Chen W-T, Hung C-C, Huang EP-C, Lee TS-H. COVID-19 stigma associates with burnout among healthcare providers: evidence from Taiwanese physicians and nurses. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121(8):1384–91.

Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, Singh A, Eid SM, Haroon Burhanullah M, et al. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1169–76.

Verma S, Mythily S, Chan Y, Deslypere J, Teo E, Chong S. Post-SARS psychological morbidity and stigma among general practitioners and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33(6):743–8.

Vani P, Banerjee D. ‘Feared and Avoided’: psychosocial effects of stigma against health-care workers during COVID-19. Indian J Soc Psychiatr. 2021;37(1):14-.

Patel BR, Khanpara BG, Mehta PI, Patel KD, Marvania NP. Evaluation of perceived social stigma and burnout, among health-care workers working in covid-19 designated hospital of India: a cross-sectional study. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2021;4(4):156.

Tari Selçuk K, Avci D, Ataç M. Health professionals’ perception of social stigma and its relationship to compassion satisfaction, burnout, compassion fatigue, and intention to leave the profession during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Work Behav Health. 2022;37(3):189–204.

Ampon-Wireko S, Zhou L, Quansah PE, Larnyo E. Understanding the effects of COVID-19 stigmatisation on job performance: a survey of frontline healthcare workers. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):2039–52.

Winugroho T, Budiarto A, Sarpono S, Imansyah M, Hidayat A. The influence of the factors of the period and place of quarantine and stigmatization on the resilience of COVID-19 survivors of nurses. In BIO Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences; 2022;49:03001. https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20224903001.

Shafiei Z, Rafiee Vardanjani L. The importance of paying attention to social stigma imposed on the healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a letter to the editor. Rums J. 2022;20(10):1169–74.

Adom D, Mensah JA, Osei M. The psychological distress and mental health disorders from COVID-19 stigmatization in Ghana. Social Sci Humanit Open. 2021;4(1):100186.

Franklin P, Gkiouleka A. A scoping review of psychosocial risks to health workers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2453.

Woga R, Budiana I, Bai MK, Purqoti DNS, Supinganto A, Lukong MAY. The effect of negative stigma of Covid-19 on nurse performance. STRADA J Ilmiah Kesehatan. 2022;11(1):59–69.

Trusty WT, Swift JK, Higgins HJ. Stigma and Intentions to seek psychotherapy among primary care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mediational analysis. Int J Behav Med. 2023;30(4):572–7.

Shafiei Z, Rafiee VL. The importance of paying attention to social stigma imposed on the healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a letter to the editor. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2022;20(10):1169–74.

Ranjit YS, Das M, Meisenbach R. COVID-19 courtesy stigma among healthcare providers in India: a study of stigma management communication and its impact. Health Commun. 2023;38(13):2833–42.

Nchasi G, Okonji OC, Jena R, Ahmad S, Soomro U, Kolawole BO, et al. Challenges faced by African healthcare workers during the third wave of the pandemic. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5(6):e893.

Siu JY-m. The SARS-associated stigma of SARS victims in the post-SARS era of Hong Kong. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(6):729–38.

WorldHealthOrganization. Social Stigma associated with COVID-19 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid19-stigma-guide.pdf.

Price J, Becker-Haimes EM, Benjamin WC. Matched emotional supports in health care (MESH) framework: a stepped care model for health care workers. Fam Syst Health. 2021;39(3):493.

Ranjit YS, Das M, Meisenbach R. COVID-19 Courtesy Stigma among Healthcare Providers in India: A Study of Stigma Management Communication and its Impact. Health Commun. 2023;38(13):2833–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2122279.

Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz M, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168(10):1245–51.

Almutairi AF, Adlan AA, Balkhy HH, Abbas OA, Clark AM. “It feels like I’m the dirtiest person in the world.”: exploring the experiences of healthcare providers who survived MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia. J Inf Public Health. 2018;11(2):187–91.

Wester M, Giesecke J. Ebola and healthcare worker stigma. Scand J Public Health. 2019;47(2):99–104.

Riegel M, Klemm V, Bushuven S, Strametz R. Self-Stigmatization of healthcare workers in intensive care, acute, and emergency medicine. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):14038.

Davtyan M, Brown B, Folayan MO. Addressing Ebola-related stigma: lessons learned from HIV/AIDS. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):26058.

Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0.

Tognotti E. Lessons from the history of quarantine, from plague to influenza A. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(2):254.

Teksin G, Uluyol OB, Onur OS, Teksin MG, Ozdemir HM. Stigma-related factors and their effects on health-care workers during COVID-19 pandemics in Turkey: a multicenter study. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2020;54(3):281–90.

Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: the consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1621–6.

Das M. Social Construction of Stigma and its Implications – Observations from COVID-19. SSRN; 2020. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3599764.

Callus E, Bassola B, Fiolo V, Bertoldo EG, Pagliuca S, Lusignani M. Stress reduction techniques for health care providers dealing with severe coronavirus infections (SARS, MERS, and COVID-19): a rapid review. Front Psychol. 2020;11:589698.

Manthorpe J, Iliffe S, Gillen P, Moriarty J, Mallett J, Schroder H, et al. Clapping for carers in the Covid-19 crisis: carers’ reflections in a UK survey. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(4):1442–9.

Naik BN, Pandey S, Rao R, Verma M, Singh PK. Generalized anxiety and sleep quality among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study from a tertiary healthcare institution in Eastern India. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives. 2022;13(1):51.

Jeleff M, Traugott M, Jirovsky-Platter E, Jordakieva G, Kutalek R. Occupational challenges of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMJ open. 2022;12(3):e054516.

Adhikari SP, Rawal N, Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Banmala S, Awal S, Bhandari G, Poudel R, Parajuli AR. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and perceived stigma in healthcare workers in Nepal during later phase of first wave of COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Cureus. 2021;13(6).

Jain S, Das AK, Talwar V, Kishore J, Ganapathy U. Social stigma of COVID-19 experienced by frontline healthcare workers of department of anaesthesia and critical care of a tertiary healthcare institution in Delhi. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine: Peer-reviewed, Official Publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2021;25(11):1241.

Osman DM, Khalaf FR, Ahmed GK, Abdelbadee AY, Abbas AM, Mohammed HM. Worry from contracting COVID-19 infection and its stigma among Egyptian health care providers. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2022;97:1–0.

Trejos-Herrera AM, Vinaccia S, Bahamón MJ. Coronavirus in Colombia: Stigma and quarantine. J Glob Health. 2020;10(2).

Wahlster S, Sharma M, Lewis AK, Patel PV, Hartog CS, Jannotta G, Blissitt P, Kross EK, Kassebaum NJ, Greer DM, Curtis JR. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic’s effect on critical care resources and health-care providers: a global survey. Chest. 2021;159(2):619–33.

Jahangasht Kh. Social Stigma: The Social Consequences of COVID-19. J Mar Med. 2021:1030/491.2.1.9.

Bagheri Sheykhangafshe F, Fathi-Ashtiani A. Psychosocial Consequences of the Post-Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Systematic Review Study. J Appl Psychol. 2022;13(3):53–72.

Do Duy C, Nong VM, Van AN, Thu TD, Do Thu N, Quang TN. COVID‐19‐related stigma and its association with mental health of health‐care workers after quarantine in Vietnam. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2020;74(10):566.

Muhidin S, Vizheh M, Moghadam ZB. Anticipating COVID‐19‐related stigma in survivors and health‐care workers: Lessons from previous infectious diseases outbreaks—An integrative literature review.

Dye T, Levandowski B, Siddiqi S, Ramos JP, Li D, Sharma S, Muir E, Wiltse S, Royzer R, Panko T, Hall W. Nonmedical COVID-19-related personal impact in medical ecological perspective: A global multileveled, mixed method study. MedRxiv. 2021;2:2020–12.

Turki M, Ouali R, Ellouze S, Ayed HB, Charfi R, Feki H, Halouani N, Aloulou J. Perceived stigma among Tunisian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. L'encephale. 2023;49(6):582–8.

Sachdeva A, Nandini H, Kumar V, Chawla RK, Chopra K. From stress to stigma–mental health considerations of health care workers involved in COVID19 management. Indian J Tuberc. 2022;69(4):590–5.

Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(7):782.

Sheather J, Hartwell A, Norcliffe-Brown D. Serious violations of health workers’ rights during pandemic. bmj. 2020;370.

Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, Singh A, Eid SM, Haroon Burhanullah M, Michtalik H, Malik M. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1169–76.

Han S, Choi S, Cho SH, Lee J, Yun JY. Associations between the working experiences at frontline of COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of Korean public health doctors. BMC psychiatry. 2021;21(1):298.

Cerit B, Uzun LN. Being a nurse at the ground zero of care in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. J Relig Health. 2022;61(1):827–50.

Hosseinzadeh R, Hosseini SM, Momeni M, Maghari A, Fathi-Ashtiani A, Ghadimi P, Heiat M, Barmayoon P, Mohamadianamiri M, Bahardoust M, Badri T. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection-related stigma, depression, anxiety, and stress in Iranian healthcare workers. Int J Prev Med. 2022;13(1):88.

Alsaqri S, Pangket P, Alkuwaisi M, Llego J, Alshammari MS. Covid-19 associated social stigma as experienced by frontline nurses of hail: a qualitative study. Int J Adv Appl Sci. 2021;8(8):52–7.

Huarcaya-Victoria J, Podestá A. Factors associated with distress among medical staff of a general hospital during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru.

Chung GK, Strong C, Chan YH, Chung RY, Chen JS, Lin YH, Huang RY, Lin CY, Ko NY. Psychological distress and protective behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic among different populations: Hong Kong general population, Taiwan healthcare workers, and Taiwan outpatients. Frontiers in medicine. 2022;9:800962.

Tirukkovalluri SS, Rangasamy P, Ravi VL, Julius A, Chatla C, Mahendiran BS, Manoharan A. Health care professional’s perceived stress levels and novel brief COPE-4 factor structure-based assessment of coping methods during COVID-19 pandemic in India: A multi-modal cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(7):3891–3900.

Spahiu F, Krasniqi Y, Elshani B. Challenges and grievances of surgical nurses during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Tari Selçuk K, Avci D, Ataç ME. Health professionals’ perception of social stigma and its relationship to compassion satisfaction, burnout, compassion fatigue, and intention to leave the profession during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Workplace Behav Health. 2022;37(3):189–204.

Acknowledgements

The research team appreciates the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Sh. and L.Z.: Contributions to conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published. L.Z. and M.Sh.: Contributions to the collection of data. M.Sh., L.Z, and R.N.: Contributions to analysis and interpretation of data, review & editing of the final draft, final approval of the version to publishing, and general supervision of the research group.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The proposal for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research Council of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, with the IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1401.341.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Negarandeh, R., Shahmari, M. & Zare, L. Stigmatization experiences of healthcare workers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 823 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11300-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11300-9