Abstract

Background

Quality indicators are standardized, evidence-based measures of health care quality. Currently, there is no basic set of quality indicators for chiropractic care published in peer-reviewed literature. The goal of this research is to develop a preliminary set of quality indicators, measurable with administrative data.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review searching PubMed/MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Index to Chiropractic Literature databases. Eligible articles were published after 2011, in English, developing/reporting best practices and clinical guidelines specifically developed for, or directly applicable to, chiropractic care. Eligible non-peer-reviewed sources such as quality measures published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Royal College of Chiropractors quality standards were also included. Following a stepwise eligibility determination process, data abstraction identified specific statements from included sources that can conceivably be measured with administrative data. Once identified, statements were transformed into potential indicators by: 1) Generating a brief title and description; 2) Documenting a source; 3) Developing a metric; and 4) Assigning a Donabedian category (structure, process, outcome). Draft indicators then traversed a 5-step assessment: 1) Describes a narrowly defined structure, process, or outcome; 2) Quantitative data can conceivably be available; 3) Performance is achievable; 4) Metric is relevant; 5) Data are obtainable within reasonable time limits. Indicators meeting all criteria were included in the final set.

Results

Literature searching revealed 2562 articles. After removing duplicates and conducting eligibility determination, 18 remained. Most were clinical guidelines (n = 10) and best practice recommendations (n = 6), with 1 consensus and 1 clinical standards development study. Data abstraction and transformation produced 204 draft quality indicators. Of those, 57 did not meet 1 or more assessment criteria. After removing duplicates, 70 distinct indicators remained. Most indicators matched the Donabedian category of process (n = 35), with 31 structure and 4 outcome indicators. No sources were identified to support indicator development from patient perspectives.

Conclusions

This article proposes a preliminary set of 70 quality indicators for chiropractic care, theoretically measurable with administrative data and largely obtained from electronic health records. Future research should assess feasibility, achieve stakeholder consensus, develop additional indicators including those considering patient perspectives, and study relationships with clinical outcomes.

Trial registration

Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/t7kgm

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines quality as “the degree to which health care services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” [1]. Formal attempts to improve quality occurred at least as early as the 1800s with Florence Nightingale, who strove to improve clinical outcomes by challenging contemporary practices, encouraging critical thinking, and promoting standardized processes thought to positively influence care [2]. In the late 20th century, Avedis Donabedian proposed a systematic framework for assessing health care quality using quantitative measures, referred to as quality indicators. Donabedian’s framework describes indicators matching 3 major categories: Structure, Process, and Outcome [3].

Structural indicators describe the attributes of a setting where care occurs. Attributes include physical facilities, clinical equipment, organizational policies, and human resources. Process indicators refer to the steps taken to provide care such as examination, treatment, care planning, and scheduling. Outcome indicators describe the effects of care on patients and populations, such as short and long-term clinical improvement, satisfaction, and costs [4, 5]. The goal of quality assessment is to improve clinical outcomes. Structural indicators are fundamental to supporting care delivery (process), which in turn, influence outcomes.

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a seminal report describing quality indicators as measurable elements of health care developed from scientific evidence, standards of practice and expert opinions that contribute to high-quality care. The 6 domains recommended in the IOM report as most relevant to health care quality include: 1. Safe; 2. Effective; 3. Patient-centered; 4. Timely; 5. Efficient; and 6. Equitable [3]. IOM domains reflect the most important aspects of health care that quality indicators should improve or maintain. Donabedian categories organize indicators according to their application. Both IOM domains and Donabedian categories are distinct, yet complementary, frameworks for classifying and developing quality indicators.

Historically, quality indicators were developed to measure hospital quality performance, which is evident in the definition still used by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: “standardized, evidence-based measures of health care quality that can be used with readily available hospital inpatient administrative data to measure and track clinical performance and outcomes” [6]. However, quality indicators are no longer confined to in-patient hospital settings. A variety of healthcare disciplines and settings have developed, and continue to develop, quality indicators. For example, the Joint Commission uses quality indicators to assess and accredit home health services, nursing care centers, behavioral healthcare, ambulatory care centers and laboratory services [7]. Individual professions and specialty groups within professions have also developed quality indicators [8,9,10,11].

Chiropractic is a health profession focused primarily on nonpharmacological care for musculoskeletal conditions, with special emphasis on the spine and related conditions [12,13,14]. Chiropractic professionals function in both private, public, and multidisciplinary practice settings [12, 15, 16]. As a health profession, chiropractic carries an ethical obligation to conduct a variety of continuous learning activities directed toward improving the quality of clinical care [17]. However, without objectively measuring key aspects of care relating to quality, systematic quality improvement activities cannot be evidence-informed. Currently, there is no standard set of quality indicators for chiropractic care published in peer reviewed literature.

Stelfox and colleagues recommend conducting a multi-step process for developing and validating quality indicators [18, 19]. The first step is conducting a systematic literature review to identify best practices and other evidence to support draft indicators obtainable from administrative data. A variety of potential validation processes should follow, using consensus and other research methods. The long-term goal of this line of research is to develop and validate a set of quality indicators for chiropractic care. The objective of this study is to identify current professional knowledge from clinical guidelines, best practice publications, and professional standards to:

-

A)

develop a preliminary set of quality indicators for chiropractic care, measurable with administrative data without the need for individual file audits;

-

B)

identify gaps and opportunities for additional quality indicator development; and

-

C)

inform future research directions for subsequent refinement and validation.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review because: 1) there was a need for systematic literature search methods designed to closely examine a topic on which limited and/or disparate knowledge exists, to identify gaps, and to systematically organize information to direct further research [20, 21]; 2) the source literature in this study was known to include non-peer reviewed sources [22]; 3) the study objectives addressed questions beyond those about effectiveness of interventions, focused instead on transforming recommendations into potential quantitative measures [21]; 4) critical appraisal of included sources was not required [23]; and 5) transparent reporting of data synthesis methods was vital [23].

This scoping review followed PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR), prospectively registered with Open Science Framework on 30 August, 2022 (https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/T7KGM) [24]. Consistent with recommendations for developing quality indicators, we used a deductive approach to identify evidence-based concepts and recommendations from clinical guidelines, best practice publications, and quality standards [3, 18]. Once identified, we transformed these findings into more specific and measurable quality indicators consistent with the frameworks proposed by Donabedian and the IOM [3, 19].

Search strategy

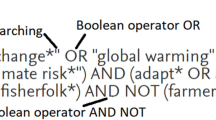

A systematic literature search was conducted by a health sciences librarian (JS) on August 31, 2022 of PubMed/MEDLINE, CINAHL (EBSCOhost interface), and Index to Chiropractic Literature databases. Results were restricted to English language studies published between January 1, 2012-August 31, 2022. Search terms consisted of subject headings specific to each database and free text words related to chiropractic, musculoskeletal pain, and quality indicators. The complete search strategies for each database are available as Supplementary file 1. The search was validated using a sample of 24 articles identified by the authors as potentially eligible and therefore should appear in search results (Supplementary file 2). General internet search engines were also used to explore potential quality indicators or other quality standards not otherwise available in peer reviewed literature. An updated search was performed on April 19, 2023 to account for potential articles published during the eligibility determination and data abstraction and transformation stage of this study. Reference searching was not employed because we only included the most recent versions of source documents.

Eligibility criteria

Because care standards, best practices, and clinical guidelines are designed to adapt as new evidence emerges, we limited our article eligibility to 10-years from our original search (2012-present) [25]. Eligible articles were written in English, measured an aspect of chiropractic care quality, and developed best practices or clinical guidelines directly applicable to chiropractic care. Non-peer-reviewed literature sources were eligible when quality indicators or quality standards pertaining to chiropractic care were included, such as quality measures published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, quality standards published by Royal College of Chiropractors, U.K., and low back pain clinical care standards published by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [26,27,28].

Ineligible articles included those that did not explicitly develop quality indicators for chiropractic care, studies reporting on the efficacy or effectiveness of interventions, guideline reviews, guidelines for other health disciplines, and epidemiological research. Best practice and guideline documents for which an updated publication was available were also ineligible. Articles reporting on studies conducted with animals, tissues, or cadaveric specimens, conference proceedings or abstracts, editorials, commentaries, articles recommending care practices based on narrative reviews, and case reports or case series, were also ineligible.

Article eligibility was assessed by 2 authors (BA, DW) in sequential steps beginning with article titles, followed by abstract review, then full text review of remaining articles. Ineligible articles were removed at each stage. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussion among both reviewers. When eligibility was unclear, the lead investigator (RV) rendered the final determination.

Data abstraction

Primary data abstraction was performed independently by 2 authors (RV, BA), with over 45 years of combined chiropractic clinical and research experience. A data abstraction form facilitated this process, which included the categories for abstracting the evidence source, condition addressed, title of potential indicator, description, corresponding Donabedian category and IOM domain(s), evidence level, and metric. Data abstraction involved identifying specific statements within the included literature that may conceivably be measured. Once identified, the statements were recorded on the data abstraction form, initiating the transformation process.

Quality indicator transformation

Quality indicator development lacks transparent methodological reporting for some healthcare disciplines [29]. We adopted a stepwise transformation process to review included literature and transform statements and recommendations into quality indicators (Fig. 1). The process included:

-

1.

Generating a brief title and descriptive statement

-

2.

Developing a Metric (e.g., policy, human or physical infrastructure description, or numerator and denominator) and documenting an evidence source

-

3.

Assigning a primary Donabedian category and relevant IOM domain

-

4.

Assessing potential quality indicators according to the following criteria [30]:

-

Describes a narrowly defined structure, process, or outcome while also matching 1 or more IOM domains: safe; effective; patient-centered; timely; efficient; equitable

-

Quantitative data can conceivably be available to measure the potential indicator

-

The performance designated is achievable by a health organization or clinician

-

The metric is relevant to those involved, such as patients, family members, clinicians, or health organizations

-

Data can be collected in aggregate within reasonable time limits

-

-

5.

Assigning an evidence level consistent with the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine model (March 2009) [31].

Graphic depiction of the quality indicator abstraction and transformation process. *Donabedian categories: Structure (attributes of a setting where care occurs such as physical facilities, clinical equipment, policies, and human resources); Process (measurable activities performed to provide care, such as examination and treatment); Outcomes (measurable effects of care on patients and populations); ‡: Institute of Medicine, now referred to as the National Academy of Medicine, United States

The transformation process included the following principles:

-

1.

Statements requiring individual file audit or clinical judgment were not transformed. (e.g., providing evidence-based care, management of comorbidities), which require consideration of multiple elements of the clinical record such as the health history, problem severity, patient preferences, and treatment response.

-

a.

When it was unclear if statements from source documents were transformable into measurable indicators, a draft was attempted and later evaluated with the assessment criteria.

-

a.

-

2.

Recommendations for elective interventions or those dependent on patient consent or preference were not transformed because such actions are optional for providers and/or patients.

-

3.

Statements, standards, and recommendations to avoid specific activities (e.g., routine imaging for acute low back pain) were not transformed because individual case-level review is needed to assess clinical reasoning and determine appropriateness.

-

4.

Statements, recommendations, and standards focused on specific conditions or presentations (e.g., neck pain, headache, pregnancy) were transformed into generalized indicators when they applied universally (e.g., Informed consent, Examination, Red flag screening).

-

5.

Though some indicators can potentially relate to multiple IOM domains, only the domain judged most relevant was assigned.

-

6.

Descriptions and metrics for some indicators, such as those derived from the Royal College of Chiropractors and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, were revised for consistent formatting.

-

7.

Comparable (i.e., redundant) indicators were combined into single indicators.

After initial data abstraction and transformation, authors (JS, ZA, DW) used a standardized checklist (Supplementary file 3) to guide critical review of each transformed potential indicator.

While we initially reported evidence levels, it became apparent that most indicators were rated with an evidence level of 5 (expert opinion or based on physiology, bench research, or first principles). Conducting separate literature reviews to confirm the accuracy of these ratings was beyond the scope of this project. Therefore, evidence rating was discontinued to avoid potential misreporting.

Results

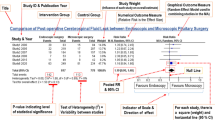

The original literature search revealed 2562 articles. A second updated search identified an additional 25 articles. After removing duplicates, 2488 articles remained. Most of the 18 articles meeting final eligibility criteria were clinical guidelines (n = 10) [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. The remaining articles consisted of best practice recommendations (n = 6) [42,43,44,45,46,47], a modified Delphi study (n = 1) [48], and a clinical appropriateness standards development study (n = 1) [49]. Figure 2 summarizes the search and eligibility determination process consistent with PRISMA recommendations. We also identified non-peer-reviewed sources meeting eligibility criteria: a clinical guideline from U.S. Veteran’s Health Affairs/Department of Defense, quality standards from the Royal College of Chiropractors (U.K.), quality measures from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and low back pain standards published by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [26,27,28, 50].

A total of 204 quality indicators were abstracted and transformed from included sources. Of those, 57 did not meet 1 or more criteria for specificity, measurement with administrative data, practicality, relevance, or timely data collection. The remaining 147 were then sorted by topic area. After combining redundant indicators, 70 unique items remained.

The largest number of indicators developed in this study match the Donabedian category of process (n = 35). These indicators were developed from statements within 19 different included sources. Most indicators relating to organizational structure (n = 31) were derived from quality standards published by the Royal College of Chiropractors (U.K.) [27]. Only 4 indicators match the Donabedian category of outcome. IOM domains from most to least common included: Effective (n = 25), Safe (n = 21), Patient-Centered (n = 16), Efficient (n = 5), Timely (n = 2), and Equitable (n = 1).

Table 1 displays titles, descriptions, and metrics for quality indicators matching the Donabedian category of structure. Table 2 displays process-related indicators, and Table 3 displays indicators related to outcomes of care.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to propose an initial set of quality indicators using scoping review methodology and a transparent process for abstracting and transforming data from recent clinical guidelines, best practice publications, and quality standards for chiropractic care. Quality standards and quality indicators share some similar characteristics. The Royal College of Chiropractors quality standards describe chiropractic care ideals while offering sample metrics, several of which are measurable through individual file audits [27]. Alternatively, this project developed indicators consistent with the definition from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which are derived largely from administrative data. Indicators obtained from administrative data offer quality assessment across a health organization while avoiding dependence on individual file audits and limitations related to inadequate sample size, and the lack of expertise and potential bias of auditors.

Angel-Garcia et al., reported 178 quality indicators for hospital-based physical therapy, several of which share similarities with those developed in this study, such as conducting an exam, obtaining informed consent, and depression screening [51]. Newell et al., demonstrated the feasibility of collecting patient reported outcomes from chiropractic patients using online survey methods [52]. More recently, Blanchette et al., proposed a set of indicators to evaluate chiropractic performance on a provincial or national scale in Canada and the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care published low back pain clinical care standards largely applicable to chiropractic [28, 48]. This study is unique for the following reasons: 1) we used systematic and transparent literature search methods; 2) we focused on developing indicators for chiropractic care at the health organization level and measurable with administrative data; 3) we developed indicators consistent with the guiding frameworks described by Donabedian and the IOM; and 4) we proposed a preliminary set of indicators for subsequent refinement and validation.

Practical considerations

Structural indicators are largely measurable through policies and documents describing a health organization, such as facilities, technical capacities, and mission [5, 53]. Most proposed process and outcome indicators are theoretically measurable with structured data contained in electronic health records, though modifying individual systems may be needed. Metrics developed in this study did not designate specific timeframes for each indicator, leaving those decisions to individual health organizations as they consider resources, goals, and other factors unique to each setting. The importance, value, and implementation of some indicators can depend on distinct characteristics of each health organization and patient population where chiropractic services are offered.

Quality indicators have historically been used in multi-provider settings. Therefore, the indicators developed in this study are likely most applicable to multi-provider organizations with the capacity to conduct ongoing quality assessment and improvement processes. Although most chiropractic care has historically been available from sole practitioners, there is a growing presence in multi-provider and multidisciplinary settings. Chiropractic services are now offered in hospital-based health systems, through corporate health organizations, and at U.S. military health treatment facilities, Olympic training centers, and Veterans Affairs facilities [54,55,56,57]. Given the increasing sophistication of electronic health records, it is conceivable that using quality indicators may also be feasible for individual providers.

Activities involved in delivering and recording health care are interrelated and complex, posing challenges for data collection and interpretation. If documenting quality indicator data impedes clinical flow, extends appointment durations, burdens provider documentation, distracts provider focus, or negatively impacts provider morale, there could be an unintended negative influence on the quality of care [58, 59]. Readers are encouraged to consider these practical factors when developing data collection methods, including what is most important for the setting, quality assessment timelines, impact on how services are delivered, and resources needed [60].

Interpreting quality indicator data

There are several factors relevant to accurately interpreting data from quality indicators proposed in this study. First, quality indicators are individually measurable components associated with quality care. No single indicator represents a comprehensive assessment of quality. Accurate interpretation may require carefully assessing data from multiple indicators combined with context knowledge about health organization characteristics, clinical processes, populations served, and an understanding of how structure, process, and outcome indicators interrelate.

For example, shared decision-making is a central attribute of patient-centered care and a feature of quality [61]. To collect shared decision-making data from electronic health records, administrative support, technological capacity, and provider training are likely needed. Should these structural elements support systematic documentation in electronic health records, data would reflect how often providers engage in shared decision-making processes. However, engaging in a process does not guarantee a desired outcome. Patient generated data (e.g., surveys) are needed to determine if the clinical processes are effective.

Second, because this study sought to propose an initial set of indicators for chiropractic care, there was a concerted effort to include those thought to be theoretically attainable rather than only those known to be attainable (e.g., those previously measured and reported such as functional outcome measures). This methodological process helped maximize the number of preliminary indicators developed in this study while minimizing unintentional author bias by presuming that indicators could be measured when it was unclear if measurement was possible [62, 63]. Further, all indicators developed in this study may not be feasible for every health organization. Additional study is needed to refine and validate these findings and to develop potentially missing indicators.

Third, quality indicators were not developed to assess appropriate imaging use because imaging decisions are dependent on multiple factors unique to each patient and clinical scenario. Quality indicators are instead designed to be derived from administrative data, without the need for individual file review. Given the persistent challenge of unnecessary imaging in healthcare [64, 65], quality improvement programs may consider if limited file review in such areas is needed.

Fourth, this study did not detect sources specifically identifying recommendations, best practices, or clinical standards generated from patient perspectives. Additional research is needed to develop meaningful indicators informed by patients. Given the initial set of indicators developed in this study, a logical next step is to begin a validation process through expert review and consensus among various stakeholders such as patients, clinicians, health system administrators, and researchers [19].

Multimodal chiropractic care plans

The sources included in this review consistently recommended multimodal chiropractic care regardless of patient population or condition. However, recommendations about multimodal care were described incongruently. For example, some clinical guideline recommendations focused primarily on specific interventions [34, 36]. Other source recommendations focused on whole person approaches, describing multimodal care in categorical terms (e.g., active care, passive care) [27, 44]. Condition-specific education was variably described, though routinely recommended as a fundamental component of care [27, 28, 32, 34, 35, 41, 47, 49]. The disparate nature of statements within source publications led to developing overlapping draft care plan indicators. To address this challenge, we developed an indicator representing a synthesis of recommendations which assess if care plans include:

-

Active therapies such as supervised or unsupervised exercise;

-

Manual therapies such as joint manipulation, mobilization, myofascial therapies, and passive muscle stretching;

-

Education about one’s condition, including pain physiology when appropriate;

-

Self-management advice and/or activities.

-

Therapeutic goals

Structuring care plans to include these categories theoretically facilitates: 1) Care consistent with existing guidelines, best-practice recommendations, and quality standards; 2) Addressing biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors; 3) Freedom to construct care plans individually; 4) Education to help patients understand a problem and make more informed decisions; 5) Applied learning focused on reducing/preventing dependence on providers and supporting self-management capacity; and 6) Active patient engagement. The multimodal care plan approach may also support outcomes beyond pain reduction. For example, education, self-management activities, and active therapies may help improve condition specific health literacy and self-efficacy while personalized care and mutually agreed goals foster therapeutic alliance [66].

Because some elements may not be needed in individual circumstances, including treatments for each intervention category should not be mandatory in every care plan. However, it is possible to efficiently document a reason why a category was not included (e.g., patient declines). In addition, the source literature obtained in this study was oriented toward care for patients with singular pain-related conditions. Future study is needed to assess if the multimodal care plan indicator proposed in this study is feasible for non-pain-focused care, such as improving or maintaining physical function, when chiropractic care is part of an interdisciplinary care plan, or when addressing more than 1 problem [67,68,69].

Limitations

Despite systematic search and eligibility determination methods, it is possible some relevant articles, including non-English publications and other non-peer reviewed sources, were missed. We used a data abstraction and transformation process including defined criteria and multiple levels of review to develop this initial set of quality indicators. Nevertheless, all indicators reported may not be measurable or necessarily contribute to health care quality in every setting where chiropractic services are available. Some overlap may exist among some indicators and data may not be obtainable in some settings due to missing or limited human and/or other infrastructure such as electronic health record systems.

Though systematic, the process of quality indicator development required human interpretation and judgment. Examples include transforming quality indicators generated from sources referencing specific conditions or patient groups (e.g., low back pain, neck pain, pediatric patients) into general indicators because the concepts were considered to apply universally (e.g., informed consent, red flag screening, multimodal care). We also combined redundant draft indicators, a process requiring human judgment. Finally, we did not assess the strength of evidence supporting each proposed indicator because performing secondary literature searches for each was beyond the scope of this project. Should the proposed quality indicators be adopted by health organizations, the data generated from their use can be used to further test, develop, and validate potential associations with clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

This article proposes a preliminary set of 70 quality indicators for chiropractic care. Most fit Donabedian categories of process and structure, highlighting a need to develop additional outcome measures, especially those meaningful to patients. Few indicators developed in this study relate to IOM categories of Timely, Equitable, and Efficient. Future work should focus on refining and expanding this preliminary set by engaging with relevant stakeholders and assessing the feasibility of collecting and analyzing quality indicator data through quality improvement/assurance processes.

Availability of data and materials

Data analyzed in this study is included in the source publications used in this research.

Abbreviations

- IOM:

-

Institute of Medicine

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews

References

Understanding quality measurement. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html. Cited 2022 May 10.

Reinking C. Nurses transforming systems of care. Nurs Manag (Harrow). 2020;51(5):32–7.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/. Cited 2022 Apr 5.

Ayanian JZ, Markel H. Donabedian’s lasting framework for health care quality. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):205–7.

Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3):Suppl:166-206.

AHRQ quality indicators. Available from: https://qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/. Cited 2022 May 10.

Facts about The Joint Commission. The Joint Commission. Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/about-us/facts-about-the-joint-commission/. Cited 2022 May 31.

Scholte M, Neeleman-van der Steen CWM, Hendriks EJM, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG, Braspenning J. Evaluating quality indicators for physical therapy in primary care. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care. 2014;26(3):261–70.

Thomaz EBAF, Costa EM, Queiroz RCDS, Emmi DT, Ribeiro AGA, Silva NCD, et al. Advances and weaknesses of the work process of the oral cancer care network in Brazil: a latent class transition analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2022;50(1):38–47.

Khawagi WY, Steinke DT, Nguyen J, Pontefract S, Keers RN. Development of prescribing safety indicators related to mental health disorders and medications: Modified e-Delphi study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(1):189–209.

Metusela C, Cochrane N, van Werven H, Usherwood T, Ferdousi S, Messom R, et al. Developing indicators and measures of high-quality for Australian general practice. Aust J Prim Health. 2022;28(3):215–23.

National Board of Chiropractic Examiners. Practice analysis of chiropractic 2020 - NBCE survey analysis. Available from: https://www.nbce.org/practice-analysis-of-chiropractic-2020/. Cited 2022 May 10.

Murphy DR. Primary spine care services: responding to runaway costs and disappointing outcomes in spine care. R I Med J. 2014;97(10):47–9.

Goertz CM, Weeks WB, Justice B, Haldeman S. A proposal to improve health-care value in spine care delivery: the primary spine practitioner. Spine J. 2017;17(10):1570–4.

Green BN, Dunn AS. An essential guide to chiropractic in the United States Military Health System and Veterans Health Administration. J Chiropr Humanit. 2021;28:35–48.

Lisi A, Brandt CA. Trends in the use and characteristics of chiropractic services in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(5):381–6.

Faden RR, Kass NE, Goodman SN, Pronovost P, Tunis S, Beauchamp TL. An ethics framework for a learning health care system: a departure from traditional research ethics and clinical ethics. Hastings Cent Rep. 2013;Spec No:S16-27.

Stelfox HT, Straus SE. Measuring quality of care: considering measurement frameworks and needs assessment to guide quality indicator development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(12):1320–7.

Stelfox HT, Straus SE. Measuring quality of care: considering conceptual approaches to quality indicator development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(12):1328–37.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Lockwood C, Dos Santos KB, Pap R. Practical guidance for knowledge synthesis: scoping review methods. Asian Nurs Res. 2019;13(5):287–94.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Vernooij RWM, Sanabria AJ, Solà I, Alonso-Coello P, Martínez GL. Guidance for updating clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review of methodological handbooks. Implement Sci. 2014;9:3.

Explore Measures & Activities. Available from: https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures. Cited 2023 Jan 24.

Quality Standards | The Royal College of Chiropractors. Available from: https://rcc-uk.org/quality-standards/. Cited 2022 May 31.

Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard | Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/clinical-care-standards/low-back-pain-clinical-care-standard. Cited 2023 May 8.

Becker M, Breuing J, Nothacker M, Deckert S, Brombach M, Schmitt J, et al. Guideline-based quality indicators-a systematic comparison of German and international clinical practice guidelines. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):71.

Lighter DE. How (and why) do quality improvement professionals measure performance? Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2015;2(1):7–11.

Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (March 2009) — Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), University of Oxford. Available from: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009. Cited 2022 Sep 7.

Bussières AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Hayden J, et al. The treatment of neck pain-associated disorders and whiplash-associated disorders: a clinical practice guideline. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(8):523-564.e27.

Bussières AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Haskett D, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy and other conservative treatments for low back pain: a guideline from the Canadian chiropractic guideline initiative. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(4):265–93.

Bussières A, Cancelliere C, Ammendolia C, Comer CM, Zoubi FA, Châtillon CE, et al. Non-surgical interventions for lumbar spinal stenosis leading to neurogenic claudication: a clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2021;22(9):1015–39.

Côté P, Wong JJ, Sutton D, Shearer HM, Mior S, Randhawa K, et al. Management of neck pain and associated disorders: a clinical practice guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. 2016;25(7):2000–22.

Côté P, Yu H, Shearer HM, Randhawa K, Wong JJ, Mior S, et al. Non-pharmacological management of persistent headaches associated with neck pain: a clinical practice guideline from the Ontario protocol for traffic injury management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Eur J Pain Lond Engl. 2019;23(6):1051–70.

Hutchins TA, Peckham M, Shah LM, Parsons MS, Agarwal V, Boulter DJ, et al. ACR appropriateness Criteria® low back pain: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(11S):S361–79.

Nijs J. Low back pain: guidelines for the clinical classification of predominant neuropathic, nociceptive, or central sensitization pain. Pain Physician. 2015;18(3;5):E333-46.

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–30.

Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, Morris CE, Baker G, Whalen WM, et al. Clinical practice guideline: chiropractic care for low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(1):1–22.

Yu H, Côté P, Wong JJ, Shearer HM, Mior S, Cancelliere C, et al. Noninvasive management of soft tissue disorders of the shoulder: a clinical practice guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Eur J Pain. 2021;25(8):1644–67.

Hawk C, Schneider MJ, Vallone S, Hewitt EG. Best practices for chiropractic care of children: a consensus update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(3):158–68.

Hawk C, Schneider MJ, Haas M, Katz P, Dougherty P, Gleberzon B, et al. Best practices for chiropractic care for older adults: a systematic review and consensus update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017;40(4):217–29.

Hawk C, Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Daniels CJ, Minkalis AL, Taylor DN, et al. Best practices for chiropractic management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a clinical practice guideline. J Altern Complement Med. 2020;26(10):884–901.

Hawk C, Amorin-Woods L, Evans MW, Whedon JM, Daniels CJ, Williams RD, et al. The role of chiropractic care in providing health promotion and clinical preventive services for adult patients with musculoskeletal pain: a clinical practice guideline. J Altern Complement Med N Y N. 2021;27(10):850–67.

Weis CA, Pohlman K, Barrett J, Clinton S, da Silva-Oolup S, Draper C, et al. Best-practice recommendations for chiropractic care for pregnant and postpartum patients: results of a consensus process. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2021;S0161475421000361:469–89.

Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, Minkalis AL, Lauretti W, Crivelli LS, et al. Best-practice recommendations for chiropractic management of patients with neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019;42(9):635–50.

Blanchette MA, Mior S, Thistle S, Stuber K. Developing key performance indicators for the Canadian chiropractic profession: a modified Delphi study. Chiropr Man Ther. 2022;30(1):31.

Wiles LK, Hibbert PD, Stephens JH, Molloy C, Maher CG, Buchbinder R, et al. What constitutes “appropriate care” for low back pain?: point-of-care clinical indicators from guideline evidence and experts (the STANDING collaboration project). Spine. 2022;47(12):879–91.

VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. U.S. Government Printing Office; 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/pain/lbp/, https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/lbp/VADoDLBPCPGFinal508.pdf.

Angel-Garcia D, Martinez-Nicolas I, Salmeri B, Monot A. Quality of care indicators for hospital physical therapy units: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2022;102(2):pzab261.

Newell D, Diment E, Bolton JE. An electronic patient-reported outcome measures system in UK chiropractic practices: a feasibility study of routine collection of outcomes and costs. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(1):31–41.

Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–8.

Goertz CM, Long CR, Vining RD, Pohlman KA, Walter J, Coulter I. Effect of usual medical care plus chiropractic care vs usual medical care alone on pain and disability among US service members with low back pain: a comparative effectiveness clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(1):e180105.

Peterson CK, Pfirrmann CWA, Hodler J, Leemann S, Schmid C, Anklin B, et al. Symptomatic, magnetic resonance imaging-confirmed cervical disk herniation patients: a comparative-effectiveness prospective observational study of 2 age- and sex-matched cohorts treated with either imaging-guided indirect cervical nerve root injections or spinal manipulative therapy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(3):210–7.

Meyer KW, Al-Ryati OY, Cupler ZA, Bonavito-Larragoite GM, Daniels CJ. Integrated clinical opportunities for training offered through US doctor of chiropractic programs. J Chiropr Educ. 2023;37(2):90–7.

Salsbury SA, Goertz CM, Twist EJ, Lisi AJ. Integration of doctors of chiropractic into private sector health care facilities in the United States: a descriptive survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(2):149–55.

Addington D, Kyle T, Desai S, Wang J. Facilitators and barriers to implementing quality measurement in primary mental health care: Systematic review. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2010;56(12):1322–31.

Arvidsson E, Dahlin S, Anell A. Conditions and barriers for quality improvement work: a qualitative study of how professionals and health centre managers experience audit and feedback practices in Swedish primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):113.

Marang-van de Mheen PJ, Vincent C. Measuring what matters: refining our approach to quality indicators. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;0:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2022-015221.

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1.

Rubin HR, Pronovost P, Diette GB. From a process of care to a measure: the development and testing of a quality indicator. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care. 2001;13(6):489–96.

Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(4):358–64.

Jenkins HJ, Downie AS, Maher CG, Moloney NA, Magnussen JS, Hancock MJ. Imaging for low back pain: is clinical use consistent with guidelines? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. 2018;18(12):2266–77.

Jenkins HJ, Kongsted A, French SD, Jensen TS, Doktor K, Hartvigsen J, et al. What are the effects of diagnostic imaging on clinical outcomes in patients with low back pain presenting for chiropractic care: a matched observational study. Chiropr Man Ther. 2021;29(1):46.

Babatunde F, MacDermid J, MacIntyre N. Characteristics of therapeutic alliance in musculoskeletal physiotherapy and occupational therapy practice: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):375.

Vining RD, Gosselin DM, Thurmond J, Case K, Bruch FR. Interdisciplinary rehabilitation for a patient with incomplete cervical spinal cord injury and multimorbidity. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(34):e7837.

Vining RD, Salsbury SA, Cooley WC, Gosselin D, Corber L, Goertz CM. Patients receiving chiropractic care in a neurorehabilitation hospital: a descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:223–31.

Eklund A, Jensen I, Lohela-Karlsson M, Hagberg J, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kongsted A, et al. The Nordic Maintenance Care program: effectiveness of chiropractic maintenance care versus symptom-guided treatment for recurrent and persistent low back pain-a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0203029.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No formal funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RV conceived the idea and designed the methodological approach for the project. JS conducted literature searches. BA, DW, and ZA conducted the article eligibility process. Data abstraction and transformation was conducted by BA and RV, with critical review steps performed by ZA, JS, and DW. RV drafted the manuscript. All authors read, edited, critically appraised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Additional file 2.

Search validation list.

Additional file 3.

Quality indicator 2nd level review checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Vining, R., Smith, J., Anderson, B. et al. Developing an initial set of quality indicators for chiropractic care: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 65 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10561-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10561-8