Abstract

Background

Vaccination is one of the most important public health interventions to reduce child mortality and morbidity. In Ethiopia, about 472,000 children die each year by vaccine-preventable diseases. A satisfied mother is assumed to use the services and complies with the service provider for better health care outcomes. However, there was no adequate evidence regarding maternal satisfaction with quality of childhood vaccination services. This study aimed to assess maternal satisfaction on quality of childhood vaccination services and its associated factors at public health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Methods

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted from 12 July to 12 August 2021 at public health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. A total of 366 mothers (caretakers) of under one-year-old children participated in the study. A systematic sampling technique with an interviewer-administered questionnaire and inventory checklist were used to collect the data. A binary logistic regression model was fitted. Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value < 0.05 were used to identify the factors associated with the outcome.

Results

Nearly two-thirds (61.2%) of mothers (caretakers) were satisfied with the quality of childhood vaccination services. Service providers’ greeting [AOR = 1.60; 95%CI: 1.37–1.99] and information about the types of vaccines [AOR = 1.54; 95%CI: 1.32–1.89] were positively associated with maternal satisfaction. On the contrary, long waiting time of mothers (caretakers) to receive services [AOR = 0.29; 95%CI: 0.14–0.62] was negatively associated with services.

Conclusion

The overall maternal satisfaction towards the quality of childhood vaccination services in this study was found to be low. Minimizing waiting time at the health facility, enhancing greetings and providing adequate information regarding childhood vaccination for mothers (caretakers) improved their satisfaction with the services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2015, about six million children died globally before the age of five, and over 3 million are died from vaccine-preventable infectious diseases [1]. In Ethiopia, about 472,000 children still die each year from vaccine-preventable diseases [2]. Majorities of childhood deaths are due to diseases that could be easily prevented with simple and affordable interventions such as vaccines [3]. Children are more susceptible to certain pathogens including vaccine-preventable infectious diseases due to their weak immunity [4]. As a result, vaccination is one of the most powerful health interventions that prevent 2–3 million deaths every year from vaccine-preventable diseases [2].

Vaccination is the process by which an individual’s immune system becomes fortified against an infectious disease by introducing a vaccine into the body that triggers an immune response [5]. Vaccines contain only killed or weakened forms of microorganisms like viruses or bacteria that do not cause the disease [6]. Vaccination is a key component of primary health care and a proven tool in preventing and eradicating infectious diseases [7]. It is a simple, safe and effective way of preventing and controlling infectious disease outbreaks [8, 9]. As a result, childhood immunization is considered a priority child health service in health facilities[10]. However, about 60% of children did not receive quality childhood vaccination services, particularly in sub-Saharan African countries [11].

The quality of childhood vaccination service depends on three domains: Structure, process, and outcome [12]. The driving forces towards the quality of childhood vaccination services include a clear understanding of the benefits of vaccination among community members, a readiness for providing vaccination by the health workers, and interventions to overcome barriers to vaccination services [13]. The quality of childhood vaccination services is also linked to the unavailability of vaccines, poor cold chain management, long waiting times, fear of side effects, long-distance travel, and being busy [14]. Maternal (caretaker) satisfaction is considered one of the most frequently used proxy indicators to measure the quality and efficiency of childhood vaccination services [11]. Accordingly, poor quality of childhood vaccination services is a major cause of morbidity and mortality of children due to vaccine-preventable diseases in developing countries[15] This can also cause a reduction in productivity, educational achievements, and economic growth [16]. A low level of maternal satisfaction with the quality of vaccination services may also enhance the self-medication of children using antibiotics associated with childhood illness among non-vaccinated children [12]. Even though there are studies in Ethiopia that evaluated the coverage of childhood immunization services [17, 18], there were no adequate evidences regarding maternal satisfaction on the quality of childhood vaccination services. Therefore, this study aimed to assess maternal satisfaction with the quality of childhood vaccination services and its associated factors at public health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study design, setting, and population

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted from 12 July to 12 August 2021 at public health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa is the capital city of Ethiopia and is the largest city in the country. According to the city administrative health department biannual profile report, the city has 11 sub-cities, 12 public hospitals and 109 public health centers, and a total population of 4,567,857. The total number of eligible populations in the city who attended the expanded program of immunization (EPI) clinic in public health centers was about 13,500 per month.

Population

All mothers (caretakers) of under one year of children who attended childhood vaccination services at health centers in Addis Ababa city administration were the source population while those mothers (caretakers) who attended vaccination services for their children in the selected health centers were the study population. All mothers (caretakers) of under one year of children who were receiving immunization services at least one schedule within the selected sub-cities of Addis Ababa were included in the study. Mothers (caretakers) of under one year of children who were, severely ill and unable to respond were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling procedures

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula. It was computed by considering that a previous study has demonstrated the proportion of maternal satisfaction towards the quality of childhood vaccination service (68.2%) [19], a 95% confidence interval, 5% margin of error, and 10% non-response which yields the final sample size 366.

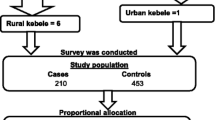

Four sub-cities and 33 health centers from these sub-cities were selected using simple random sampling. Then, the proportional allocation was done to each selected health center based on the previous one-month vaccination performances. Finally, a systematic sampling technique was employed and study participants were selected in every 3rd interval.

Variables and measurements

The dependent variable was maternal satisfaction on the quality of childhood vaccination service while sociodemographic status, infrastructures, process, and access factors were the independent variables. Maternal satisfaction with the quality of childhood vaccination service was measured in eight items, each containing a five-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied) alternatives. Therefore the total score could be ranged from 8–40 and then we used the demarcation threshold formula: \(((\frac{\mathrm{Total}\;\mathrm{highest}\;\mathrm{score}\;-\;\mathrm{Total}\;\mathrm{lowest}\;\mathrm{score}}2)\;+\;\mathrm{Total}\;\mathrm{lowest}\;\mathrm{score})\) [20] to categorize the level of mothers(caretakers) satisfaction as “satisfied and dissatisfied”. Accordingly, mothers (caretakers) who scored above 60% on the satisfaction measurement tools were considered as satisfied otherwise not dissatisfied.

Data collection tools and procedures

A pre-tested interviewer-administered structured questionnaire was used to collect data. The data collection tool was adapted by reviewing a variety of literature [1, 21]. Furthermore, the Ethiopian Ministry of Health (MoH) inventory checklist was used to collect data related to the structure factors and process factors. The data collection tool was first prepared in English, translated to Amharic (the local language) then retranslated to English to check for consistency. Data collection was facilitated by four trained BSC nurses and two BSC midwifery nurse supervisors.

Data quality assurance and control

A day of training was given for both data collectors and supervisors on the data collection methods and procedures. The data collectors were followed by supervisors daily. To enhance instrument reliability, the instrument was pre-tested on 5% of sampled mothers (caretakers) of under one year children outside of the study area nearby healthcare facilities with similar characteristics to those in the study. The data was collected after a brief explanation of the aim of the study to the participants. The validity and completeness of the collected data were verified by the principal investigator and supervisors daily.

Data processing and analysis

Data were cleaned and entered into Epi info version 7.2.2.2 and exported to SPSS version 23 statistical software for analysis. A binary logistic regression was fitted to determine the association between dependent and independent variables. Variables with a p-value of less than 0.2 during bivariable regression were entered into multivariable logistic regression. Adjusted Odd Ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval and p-value < 0.05 were used to declare the significant factors and strength of association. The model fitness was checked using the Hosmer Lemeshow goodness of fit test (88.6%) indicating that the model fitness was good. Descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentages, mean, and standard deviation (SD) were presented in the form of texts and tables.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 366 mothers (caretakers) of under one year children participated with a response rate of 100%. The mean age of mothers/caretakers was (25.6 ± 6.7 SD) years. More than one-third (41.5%) of the participants were housewives and 85.4% were married (Table 1).

Availability of infrastructures

All health centers had separate immunization rooms and 97.0% of them had a separate waiting area with chairs. Most health centers (97.0%) had adequate immunization registration books and tally sheets. Less than three-fourths (72.7%) of the health centers had pipe water. All health centers had at least one refrigerator whereas, 21.2% of health centers did not have a separate room for refrigerators and cold boxes (Table 2).

Access to vaccination services

The majority (80.9%) of mothers (caretakers) judged that the service was located at a convenient distance from their home. Moreover, 39.1% of mothers waited more than 45 min to receive the services (Table 3).

Process-related factors to vaccination services

Three-fourths (76.0%) of mothers (caretakers) had gotten vaccination services as per their previous appointments. About two-thirds (69.9%) of mothers (caretakers) were informed about the use and side effects of the administrated antigens but only 35% of them were informed about the types of vaccines given to their child. About 36.9% of mothers (caretakers) had gotten a proper greeting from the health care providers during their child vaccination session (Table 4).

Maternal satisfaction and its associated factors

Nearly two-thirds (61.2%) of mothers (caretakers) were satisfied with the overall quality of childhood vaccination services. Two-thirds (65.3%) and 61.2% of mothers/caretakers were satisfied with the cleanliness and availability of services, respectively. On the other hand, over half (52.0%) of mothers/caretakers were dissatisfied with access to drinking water, latrine, and hand-washing facilities (Table 5).

Factors associated with maternal satisfaction

In the final multivariable logistic regression analysis, waiting time at the vaccination unit service provider greetings, and information about the types of vaccines were factors associated with mothers' (caretakers) satisfaction with the quality of vaccination services. The odds of client satisfaction with the quality of services among mothers (caretakers) waiting 30–45 min to receive services is significantly lower as compared to those who waited below 15 min [AOR = 0.38; 95%CI: 0.19–0.78]. Moreover, the odds of client satisfaction with the quality of services among mothers (caretakers) who had got greeting from providers was 1.60 times higher [AOR = 1.60; 95%CI: 1.37–1.99] as compared with their counterparts. Mothers (caretakers) who had got information about the types of vaccines were satisfied 1.54 times [AOR = 1.54; 95%CI: 1.32–1.89] compared with those who did not get information about the types of vaccines (Table 6).

Discussion

The overall maternal satisfaction towards the quality of childhood vaccination services in this study was found to be low. We also found that the major constraints that determine the satisfaction of mothers (caretakers) towards vaccination services were waiting time at the vaccination unit, service provider greetings, and information about the types of vaccines were factors associated with mothers' (caretakers’) satisfaction towards the quality of vaccination services.

Moreover, the finding of this study was relatively similar to the finding from Ondo State in Nigeria and North Wollo, Ethiopia which reported that the overall maternal satisfaction towards the quality of childhood vaccination services was (68.2%) and (68.9%) respectively [22, 19]. This consistency might be due to the similarity of the vaccination services delivery system.

Furthermore, the finding of this study was relatively higher as compared with the finding reported from Egypt (63%) [23], Calabar, south Nigeria (43.6%) [24], and Jigjiga, Ethiopia (30.1%) [25], However, the finding of this study was lower when compared with findings from New Cairo district, Egypt (74.4%) [26], Suez governorate, Egypt (95.2%) [27], Sokoto metropolis, Nigeria (75%) [28], Kombolicha, Ethiopia (71.9%) [21] and Hawasa city, Ethiopia (76.7%) [20]. This variation might be due to the existence of differences in cultural context towards vaccination services, and service delivery systems. Moreover, differences in the provision of refreshment training on vaccination services and healthcare providers' tendency towards using vaccination services guidelines and protocols might be attributed to the observed differences.

In this study, a long waiting time to find the services was found to be negatively influenced mothers' (caretakers) satisfaction. Mothers (caretakers) who had a waiting time of 30–45 min for service at the vaccination unit were less likely to be satisfied with the quality of childhood vaccination services compared with their counterparts. This finding was similar to the finding in Wadla district, Ethiopia [19], Kombolicha, Ethiopia [21], Jigjiga, Ethiopia [25], and India [14]. The possible justification might be because serving with short waiting time might be linked with accessing the services early and this could also increase the satisfaction of mothers (caretakers) towards the quality of childhood vaccination services.

Moreover, a friendly relationship between health care providers and mothers (caretakers) positively influenced mothers’ (caretakers’) satisfaction. Mothers (caretakers) who got greetings from providers were more likely to be satisfied with the quality of childhood vaccination services compared with mothers (caretakers) who did not get greetings. This finding was supported by the findings in Wadla district, Ethiopia [19], and Kombolicha, Ethiopia [21]. The possible justification might be due to effective interaction between service providers and service caretakers can contribute to the motivation of mothers' acceptance towards the vaccine services and it also increases the satisfaction of mothers with childhood vaccination services.

Information about the types of vaccines was also a significant predictor of maternal satisfaction with the quality of childhood vaccination services. Mothers (caretakers) who got information about the types of vaccines were 1.54 times more likely to be satisfied with the quality of childhood vaccination services than those who did not have information. The finding of this study was similar to a study conducted in Wadla district, Ethiopia [19], Jigjiga, Ethiopia [25] and Kombolcha city, Ethiopia [21]. This might be because having proper information about the types of vaccines enhances mothers' awareness so that they may have acceptance towards the services.

Limitations of the study

The limitation of this study is that it lacked qualitative aspects in assessing maternal satisfaction with the quality of childhood vaccination services and its associated factors. The other possible limitation of the study was that there might be a social desirability bias.

Conclusion

The maternal satisfaction with the quality of childhood vaccination services in this study was low. Long waiting time to find the services was found to be negatively influenced mothers' (caretakers) satisfaction. Moreover, a friendly relationship between health care providers and mothers (caretakers) positively influenced mothers' (caretakers') satisfaction. Precise and adequate information about the types of vaccines was also a positive predictor of maternal satisfaction with the quality of services.

Therefore, health sectors at each level and non-governmental organizations should work to improve the accessibility of services to caretakers. Healthcare providers should provide adequate information to mothers (caretakers) about vaccines and should have friendly interactions with mothers (caretakers). Moreover, healthcare providers had better adhere to vaccination services protocol. We also recommended future researchers to evaluate the quality of the services using a qualitative approach to get more general information.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odd Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- EPI:

-

Expanded Program on Immunization

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

GebreEyesus FA, Assimamaw NT, GebereEgziabher NT, Shiferaw BZ. Maternal satisfaction towards childhood immunization service and its associated factors in Wadla District, North Wollo, Ethiopia, 2019. Int J Pediatr. 2020;2020:1–13.

Meleko A, Geremew M, Birhanu F. Assessment of child immunization coverage and associated factors with full vaccination among children aged 12–23 months at Mizan Aman town, bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. 2017;2017:7976587.

Abadura SA, Lerebo WT, Kulkarni U, Mekonnen ZA. Individual and community level determinants of childhood full immunization in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–10.

Desalew A, Semahegn A, Birhanu S, Tesfaye G. Incomplete vaccination and its predictors among children in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Pediatr Health. 2020;7:2333794X20968681.

Eshete A, Shewasinad S, Hailemeskel S. Immunization coverage and its determinant factors among children aged 12–23 months in Ethiopia: a systematic review, and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:1–13.

Wondimu A, Cao Q, Asuman D, Almansa J, Postma MJ, van Hulst M. Understanding the improvement in full childhood vaccination coverage in Ethiopia using Oaxaca–blinder decomposition analysis. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):505.

Chanie MG, Ewunetie GE, Molla A, Muche A. Determinants of vaccination dropout among children 12–23 months age in north Gondar zone, northwest Ethiopia, 2019. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246018.

Lakew Y, Bekele A, Biadgilign S. Factors influencing full immunization coverage among 12–23 months of age children in Ethiopia: evidence from the national demographic and health survey in 2011. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–8.

Theodros G, Ibrahim K, Abebe B, Atkure D, Mekonnen T, Habtamu T, Kassahun A, Terefe G, Yibeltal A, Amha K. Child health service provision in Ethiopia: outpatient, growth monitoring and immunization. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2017;31(2):67–74.

Adamu AA, Uthman OA, Wambiya EO, Gadanya MA, Wiysonge CS. Application of quality improvement approaches in health-care settings to reduce missed opportunities for childhood vaccination: a scoping review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(11):2650–9.

Ropero-Álvarez AM, El Omeiri N, Kurtis HJ, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Ruiz-Matus C. Influenza vaccination in the Americas: progress and challenges after the 2009 A (H1N1) influenza pandemic. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(8):2206–14.

Klugman KP, Black S. Impact of existing vaccines in reducing antibiotic resistance: primary and secondary effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(51):12896–901.

Abodunrin O, Adeomi A, Adeoye O. Clients’ satisfaction with quality of healthcare received: Study among mothers attending infant welfare clinics in a semi-urban community in South-western Nigeria. Sky J Med Med Sci. 2014;2(7):45–51.

Tesema GA, Tessema ZT, Tamirat KS, Teshale AB. Complete basic childhood vaccination and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in East Africa: a multilevel analysis of recent demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–14.

Streefland PH. Public doubts about vaccination safety and resistance against vaccination. Health Policy. 2001;55(3):159–72.

Abdulrahman M, Habeeb Q, Teeli R. Evaluation of child health booklet usage in primary healthcare centres in Duhok Province. Iraq Public Health. 2020;185:375–80.

Nour TY, Farah AM, Ali OM, Abate KH. Immunization coverage in Ethiopia among 12–23 month old children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–12.

Mohamud AN, Feleke A, Worku W, Kifle M, Sharma HR. Immunization coverage of 12–23 months old children and associated factors in Jigjiga District, Somali National Regional State. Ethiopia BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–9.

GebreEyesus FA, Assimamaw NT, GebereEgziabher NT, Shiferaw BZ. Maternal satisfaction towards childhood immunization service and its associated factors in Wadla District, North Wollo, Ethiopia, 2019. Int J Pediatr. 2020;2020:1–3.

Dana E, Asefa Y, Hirigo AT, Yitbarek K. Satisfaction and its associated factors of infants’ vaccination service among infant coupled mothers/caregivers at Hawassa city public health centers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(3):797–804.

Hussien A. Assessment of Maternal Satisfaction Towards Childhood Immunization and Its Associated Factors in MCH Clinic, at Kombolcha, in Amhara Regional State. Northern Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University; 2015.

Babalola TK. Client satisfaction with maternal and child health care services at a public specialist hospital in a Nigerian Province. Turk J Public Health. 2016;14(3).

El Gammal HAAA. Maternal satisfaction about childhood immunization in primary health care center, Egypt. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:157.

Udonwa N, Gyuse A, Etokidem A, Ogaji D. Client views, perception and satisfaction with immunisation services at Primary Health Care Facilities in Calabar, South-South Nigeria. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2010;3(4):298–301.

Salah AA, Baraki N, Egata G, Godana W. Evaluation of the quality of Expanded Program on immunization service delivery in primary health care institutions of Jigjiga Zone Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia. Euro J Prev Med. 2015;3(4):117–23.

Ebeid Y. The acceptability of the Family Health Model, that replaces Primary Health Care, as currently implemented in Wardan Village, Giza, Egypt. 2016.

El HAAAR. Maternal satisfaction about childhood immunization in primary health care center, Egypt. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18.

Timane AJ, Oche OM, Umar KA, Constance SE, Raji IA. Clients’ satisfaction with maternal and child health services in primary health care centers in Sokoto metropolis, Nigeria. Edorium J Mater Child Health. 2017;2:9–18.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Kotebe Metropolitan University College of Medicine and Health Science for its technical support throughout this study. We would also extend our appreciation to supervisors, data collectors, and study participants.

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. ET collected data and performed the analysis. AD, FS, and TZT participated in the designing of methods and tools and revised the analysis. ET and AD prepared the draft manuscript, then FS and TZT revised the final drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the ethical procedures were followed per the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of Menelik II Medical and Health Science College, Kotebe Metropolitan University (Ref. No.

13994/227). A permission letter was obtained from Addis Ababa Public Health Research and Emergency Management Directorate. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant after a brief explanation of the research objectives and data collection process of the study. For study participants aged under 16 years or illiterates, informed consent was taken from their parents or legal guardians. Participants were also informed about their right to withdraw at any time or to skip questions. Finally, the confidentiality of the information was maintained by using coding.

13994/227). A permission letter was obtained from Addis Ababa Public Health Research and Emergency Management Directorate. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant after a brief explanation of the research objectives and data collection process of the study. For study participants aged under 16 years or illiterates, informed consent was taken from their parents or legal guardians. Participants were also informed about their right to withdraw at any time or to skip questions. Finally, the confidentiality of the information was maintained by using coding.

Consent for publication

It is not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tesfaye, E., Debie, A., Sisay, F. et al. Maternal satisfaction on quality of childhood vaccination services and its associated factors at public health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 1315 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10174-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10174-7