Abstract

Background

Inadequate healthcare access and utilisation are implicated in the mental health burden experienced by those living in regional, rural, and remote Australia. Facilitators that better enable access and utilisation are also reported in the literature. To date, a synthesis on both the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services within the rural Australian context has not been undertaken. This scoping review aims to (1) synthesise the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services in regional, rural, and remote Australia, as identified using the Modified Monash Model; and (2) better understand the relationship between barriers and facilitators and their geographical context.

Methods

A systematic search of Medline Complete, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Scopus, and CINAHL was undertaken to identify peer-reviewed literature. Grey literature was collated from relevant websites. Study characteristics, including barriers and facilitators, and location were extracted. A descriptive synthesis of results was conducted.

Results

Fifty-three articles were included in this scoping review. Prominent barriers to access and utilisation included: limited resources; system complexity and navigation; attitudinal and social matters; technological limitations; distance to services; insufficient culturally-sensitive practice; and lack of awareness. Facilitators included person-centred and collaborative care; technological facilitation; environment and ease of access; community supports; mental health literacy and culturally-sensitive practice. The variability of the included studies precluded the geographical analysis from being completed.

Conclusion

Both healthcare providers and service users considered a number of barriers and facilitators to mental health service access and utilisation in the regional, rural, and remote Australian context. Barriers and facilitators should be considered when re-designing services, particularly in light of the findings and recommendations from the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, which may be relevant to other areas of Australia. Additional research generated from rural Australia is needed to better understand the geographical context in which specific barriers and facilitators occur.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The mental health of Australians who live in regional, rural, and remote Australia is an ongoing concern [1]. Poor healthcare access is one of the key determinants of adverse mental health outcomes, with access issues being more pronounced in regional, rural, and remote Australia (hereafter referred to as rural, in line with the Australian Government’s definition under the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training [RHMT] Program [2]), compared to metropolitan Australia [3]. People living in rural Australia often face difficulties in obtaining healthcare, and this care is often delayed and more expensive for the patient [4]. These difficulties in accessing and utilising healthcare are implicated in the higher mental disorder burden experienced by those living in rural Australia, shown by the higher rates of suicide, compared with major cities [5]. Moreover, this group is less likely than those living in major cities to take-up and complete mental health treatment [6]. Workforce maldistribution plays a role in these health inequalities [7,8,9,10], with more clinical full time equivalent (FTE) mental health professionals working in major cities, compared with rural areas (i.e., 92 vs. 30–80 mental health nurses, 15 vs. 2–6 psychiatrists, and 90 vs. 15–55 psychologists per 100,000/population) [3]. Other areas of the health workforce are similarly maldistributed across the country (i.e., 403 vs. 223–309 clinical FTE medical practitioners and 531 vs. 382–469 clinical FTE allied health professionals per 100,000/population in major cities versus rural areas) [11].

There are a number of factors that are implicated — both directly and indirectly — in the access and utilisation of mental health services, and these factors may be pertinent to the level of remoteness experienced. This includes particular aspatial (i.e., social) and spatial (i.e., geographical) dimensions [12, 13]. Aspatial dimensions consist of the factors that affect the affordability, acceptability, accommodation, and awareness of healthcare access. In the rural context of Australia, this tends to relate to social matters [14, 15] including stoicism, low help-seeking behaviours, and confidentiality concerns [16]. Spatial dimensions are concerned with the availability and accessibility of service access, including geographical isolation [14], service delivery capacity [17] [18], and dual-roles [14] (i.e., the intersection of professional and personal relationships) in rural areas. While here we define access as factors that pertain to the attributes/expectations of the individual and their alignment with the provider/services [12], other models conceptualise access as the opportunity to identify healthcare needs, seek services, reach resources, obtain or use services, and have the need for services fulfilled [19]. Utilisation refers to the generation of a healthcare plan throughout a healthcare encounter, as well as its implementation and follow-through [20].

Conceivably, mitigating the barriers and augmenting the facilitators to the utilisation of mental health services may be particularly important when considering the obstacles that people from rural areas face when accessing services. One previous study on rurally-based Australian adolescents suggested that barriers to accessing services, such as social exclusion and ostracism by members of their community, also likely prevented the continued utilisation of services and negatively affected treatment outcomes [21]. Cheesmond et al. [22], in a review of residents in rural Australia, Canada, and the United States of America, highlighted a link between sociocultural rurality, rural identity, and help-seeking behaviour. Cheesmond et al. [22] suggested that specific place-sensitive approaches are needed to overcome barriers to help-seeking, and that a greater understanding of help-seeking in the rural context is required. This includes further exploration of rurality as a concept, conducting research within diverse environments, allowing participants to contextualise barriers to help-seeking, and exploring the co-existence of multiple help-seeking barriers. Parallel to this, a paucity of research has focussed on the facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services in rural Australia.

To the authors’ knowledge, no previous reviews have specifically focussed on understanding the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services within the rural Australian context. A scoping review was chosen as the preferred approach to this work because of the emerging and cross-disciplined nature of the research. The aim of this scoping review is to: (1) explore the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services for Australians living in rural areas; and (2) better understand the relationship between barriers and facilitators and their geographical context.

Method

This scoping review conforms to the guidelines put forward by Arksey and O’Malley [23], follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [24], and a published protocol [25].

Eligibility criteria

The scope of this review was intentionally broad to allow explanation of the nature and extent of the literature describing the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services across regional, rural, and remote Australia. Articles were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

-

Included individuals with a diagnosed mental disorder, experienced mental health issues, or were part of a mental health community service; or included healthcare providers that provided diagnostic, assessment, or treatment services for mental health issues.

-

Explained obstacles that impeded the uptake, quality, or level of mental health services being accessed or described facilitators that allowed the uptake, quality, or level of mental health services being received.

-

Included service users, healthcare providers, or services that were based in regional, rural, or remote Australia according to the Modified Monash Model (MMM) 2–7 (regional centres to very remote communities) [4] (i.e. the current RHMT definition of rural).

The population/concept/context (PCC) framework was used to generate the eligibility criteria for this scoping review and is described in Table 1. The eligibility criteria for this review varied slightly from the published protocol [25]. In this review, we included pharmacists as healthcare providers, as it was identified that pharmacists play a key role in mental health services in some rural areas. We excluded mental health programs and health promotion activities that were considered to be a “structured activity” delivered by a service, reviews, viewpoints, declarations, tailpieces, frameworks, and commentaries. We also excluded articles that did not provide sufficient detail to describe the barriers or facilitators to accessing or utilising services, as well as articles that pooled results across participants from metropolitan and regional/rural/remote areas. The only exception to this was when authors referred to the study setting as regional/rural/remote, but upon further investigation using the health workforce locator [26] (see Sect. 2.8Geographical analysis), the location was deemed to be metropolitan according to the MMM [4] — this exception was allowed due to the differences in geographical models applied to Australian health research [27, 28]. Separately, we decided to include articles that reported on the barriers and/or facilitators of a specific rural mental health service implementation activity or service model, as we felt that these articles offered important insights that may be translated to new service initiatives or research activities.

Information sources

The following databases were systematically searched: Medline Complete, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Websites of the Australian federal and state government’s Department of Health, Primary Health Network (PHN), key rural and remote peak bodies/agencies known to the authors from their collective experience on the topic, and Google were also searched to ascertain grey literature. The search was performed on 11th January 2022 and a 2012-current date filter was employed using the ‘start’ and ‘end’ publication year functions. Additional sources were identified through ‘snowball’ searching of included studies. Where needed, additional location information was obtained via a study’s first or corresponding author.

Search

The search strategy was developed in consultation with two scholarly services librarians (JS and BK) to identify peer-reviewed studies and grey literature records. Relevant keywords, search terms, and wildcard symbols were applied to each database. An adapted search string was searched in Google using the advanced search function. The “all these words” and “any of these words” search options were engaged, and PDF files were requested. All (n = 11) pages of the search results were assessed for eligibility by one reviewer (BEK), and the research term agreed on their inclusion.

The full search strategy and grey literature sources are presented in Additional Table 1.

Selection of sources of evidence

One reviewer (BEK) applied the search strategy to the databases and websites. Two reviewers (BEK and KBC) independently screened all articles using Covidence [29]. Where discrepancies concerning the eligibility of an article occurred, a meeting was held to determine consensus; if consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer (LJW) was consulted to make the final decision.

Data charting process

To ensure that the data charting process was consistent with the research question, a charting form was developed and piloted by two authors (BEK and KBC). One author (BEK) then charted the data for each of the eligible articles, using Microsoft Excel.

Data items

The following data items were extracted from eligible studies: author and year, study objective, study design, location, sample size, characteristics of participants, mental health diagnosis/issue and assessment method, healthcare provider type/role, barriers, facilitators, mental health service, regional/rural/remote area of Australia, and summary of findings (Additional Table 2). For literature that included participants from both metropolitan and regional/rural/remote areas, only information that pertained to those from regional/rural/remote areas was extracted, except for instances where statistical differences between groups were reported for comparison. Likewise, in instances where articles included participants who were eligible (e.g., healthcare providers) as well as participants who were ineligible (e.g., no evidence of mental health diagnosis/engagement with services), only information from eligible participants was extracted. First or corresponding authors of studies that did not specifically state where the study was conducted were contacted to provide additional location information.

Synthesis of results

A descriptive synthesis was conducted by providing an overview of the included study characteristics, setting and target groups, and barries and facilitators. Links to aspatial and spatial access factors were also described, where relevant. The study characteristics are presented in Table 2 and the barriers and facilitators pertaining to each included study are presented in Additional Table 3. A quality appraisal of the included studies was not undertaken as scoping reviews aim to offer an overview or map of the pertinent evidence [30].

Geographical analysis

Geographical coordinates provided by the health workforce locator [26] were used to determine the remoteness of the study locations according to the MMM categories. These data were inputted into STATA to determine the number and proportion of each of the MMM categories.

Results

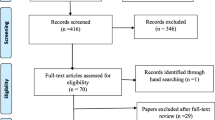

The database search yielded 1,278 articles, of which 555 articles were removed due to duplication. Subsequently, 723 titles and abstracts were screened, and 441 were excluded due to ineligibility. At the full text stage, 282 articles were screened, with 181 studies being excluded, resulting in 47 articles meeting the eligibility criteria. The grey literature search yielded 128 potentially relevant sources, of which six were eligible after removing three for duplication. In total, 53 articles were included in this scoping review. A snowball search of the references of included records was also conducted and two additional records were identified but were deemed ineligible as they reported on studies/samples that were already included in the review. Figure 1 displays the PRISMA flow throughout each screening stage.

Study characteristics

Of the 53 included studies, 25 articles described barriers and/or facilitators from the healthcare provider perspective, 13 were from the point of view of the service user, eight reported on combined perspectives of both the healthcare provider and service user, and seven reported on barriers/facilitators from neither the healthcare provider nor service user perspective directly but did consider the barriers/facilitators of the service environment (e.g., service evaluations).

Most studies (n = 29, 54.7%) employed qualitative methods, including interviews and/or focus groups; 12 studies utilised quantitative cross-sectional or longitudinal methods, seven were mixed-methods research designs, and two were service description and classification studies.

The highest proportion of studies were conducted in New South Wales (NSW) (n = 13) [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], followed by Australia broadly (n = 12) [33, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54], South Australia (SA) (n = 10) [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64], Victoria (VIC) (n = 6) [65,66,67,68,69,70], Queensland (QLD) (n = 5) [71,72,73,74,75], Western Australia (WA) (n = 3) [76,77,78], Tasmania (TAS) (n = 2) [79, 80], and Northern Territory (NT) (n = 1) [81]. One study pertained to areas within NSW, QLD, and VIC [82], and another study concerned NSW and WA [83]. No studies were centred on Australian Capital Territory (ACT). Table 2 depicts the characteristics of the included studies.

Setting and target groups

Mental health service setting

Fourteen studies reported on general or community-based mental health services [18, 33, 43, 48, 53, 54, 57, 64, 72, 74, 77, 78, 83]. Four studies described mental health services provided within emergency departments (EDs) and/or urgent care centres (UCCs) [40, 41, 46, 65]. The remaining studies described mental health services provided by counsellors and GPs [38], nurses, peer-workers [71], personal helpers and mentors [35], pharmacists [47], and a combination of several healthcare providers [59]. Seven studies reported on technology-based or -enhanced mental health services [51, 60,61,62,63, 75, 76].

Target groups

The population group focus of studies varied. Of the studies that commented on, or specified that they targeted specific subpopulations, four studies discussed care pertinent to Indigenous or Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Peoples [66,67,68, 81]. Four studies discussed mental health services for young people [55, 63, 73, 82]. Three studies specifically included at least a proportion of service users who were under the age of 18 years old [55, 61, 79]. Two studies reported on mental health services for older people [50, 58]. Other studies described barriers and or facilitators specific to sex workers [80], medical doctors [45], LGBTIQA + people [51], immigrants [49], and women [39] or men [70] with specific mental health issues. Three studies described mental health services that were specific for supporting people with depression [34, 39, 55]; two studies were focussed on suicide [68, 70]; two studies described care for people with eating disorders [42, 52]; and one study was centred on perinatal and infant support [75].

Barriers and facilitators

The included studies varied significantly. This included differences in the purpose and type of study, participant sample, and methodology, and reporting of findings. Barriers and facilitators were grouped into prominent concepts based on terminology used by the relevant literature and are presented in Table 3. Barriers related to limited resources; system complexity and navigation; attitudinal and social matters; technological limitations; distance to services; insufficient culturally-sensitive practice; and lack of awareness. Facilitators related to person-centred and collaborative care; technological facilitation; environment and ease of access; community supports; mental health literacy; and culturally-sensitive practice.

Prominent barrier concepts

Barriers affecting healthcare providers and service users

Limited resources. Across the studies, the most considerable barrier was limited resources [18, 33,34,35,36, 38, 39, 42, 45, 50,51,52,53,54,55,56, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66, 71, 74, 75, 78,79,80, 82]. This key concept considered limited resources at the healthcare provider and service user level. Notably, lack of available general and specialist services, limited service capacity, workforce shortages, difficulty attracting and retaining staff, and staff turnover were frequently reported as considerable spatial barriers to service delivery, hampering access to services. Moreover, financial costs, disadvantage, or appointment fees [34, 37, 52, 53, 61, 62, 78], and lack of transport [34, 50, 52, 53, 58, 62, 71, 78] restricted access to mental health services for the service user. These issues reflect the lower relative socio-economic advantage seen in rural areas of Australia [2].

System complexity and navigation. The complexity in using and navigating the system was a common aspatial barrier [18, 33, 36, 40,41,42, 45, 46, 51,52,53, 57,58,59, 61, 63, 65, 66, 69, 73, 74, 78, 80], which affected healthcare providers in coordinating patient care and service users in utilising such care. These issues were most frequently reflected in reports on extended wait times and delays in assessment and diagnosis [34, 40, 46, 53, 55, 57, 58, 62, 66, 78, 80].

Attitudinal or social matters. Many studies reported that attitudinal or social matters were a barrier for the service user [34,35,36, 38, 39, 43, 50,51,52, 60, 61, 64, 66,67,68, 70, 78, 80, 81], particularily concerning privacy or confidentiality concerns [39, 51, 60,61,62,63, 66, 67, 78], affecting aspatial access to care. The need to be stoic was reported as a barrier to seeking psychological help among regional medical doctors, relating to their perceptions of regional practitioner identity [45], and among service users [50, 67, 70].

Technological limitations. Several studies cited limitations to services delivered via technological means [51, 53, 60,61,62, 64, 78]. Some studies acknowledged that technology can enhance physical mental health services, but cannot replace them [62, 64], particularly for specific client groups, including the older population and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, who reportedly prefer face-to-face service delivery [78]. In addition, poor connectivity and high costs of technology use were reported as aspatial barriers to accessing technology-delivered mental health services and may also affect their utilisation [53, 62, 78].

Lack of awareness. Lack of awareness about mental health issues, needs, or services available was reported as an aspatial barrier in the current review [43, 50, 52, 67, 78]. This lack of awareness was reported at the healthcare provider level in one study, and was described as the healthcare provider having a limited understanding of the mental health needs in older people, resulting in a lack of referral to appropriate services [50]. At the service user level, a lack of awareness precluded individuals from recognising mental health problems [67], while a lack of awareness of services was a barrier to seeking help [52, 78].

Barriers affecting service users

Distance to services. The spatial distance required to travel to physical services is a considerable issue for people residing in rural localities, and this distance has been shown to reduce service access and utilisation in the current review [52, 62,63,64, 67, 71, 78]. There is also an additional burden experienced by those with physical disability, or those who don’t have a support person to assist them [53].

Insufficient culturally-sensitive practice. A limited capacity to meet the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities was reported, affecting aspatial access and utilisation of services. This tended to be a result of service users not feeling culturally safe within the service environment, perceptions that health professionals had cultural assumptions about the service user, and inappropriate assessment tools [48, 49, 58, 73, 78].

Prominent facilitator concepts

Facilitators affecting healthcare providers and service users.

Person-centred and collaborative care. Many studies reported that person- (or client-) centred care that is non-judgemental and permits collaboration to be an important aspatial facilitator to mental health service access and utilisation [31, 34,35,36, 41, 42, 56,57,58,59, 61, 63,64,65, 72, 74, 81]. It is noteworthy that person centred care was specifically reported in studies pertaining to the service user [61] and healthcare provider [63, 64] in the current review, suggesting that this approach is recognised as important by both those delivering and using the service. Care that is regular and non-intrusive was seen as a way to facilitate service utilisation [34, 57].

Technological facilitation. Technology-based services, including integrated mental health services, telehealth, live chat, SMS appointment reminders and coordination, and mental health web-pages, were reported to be useful in filling spatial and aspatial gaps in service delivery for physical services [51, 53, 58, 60,61,62,63, 75, 76, 78]. These services were reported to facilitate connection and information sharing [62], clinical supervision, contact with specialists [60], workforce upskilling, and security [75] for the healthcare provider. For the service user, technology-based services facilitated immediacy of consultations, cost savings, and anonymity, and reduced mental health hospitalisations and admissions, additional client appointments, the need to travel, stigma, and family stress [60].

Environment and ease of access. The mental health service environment and the ease of which one may access services — granted that all other access issues are overcome — were frequently reported as spatial facilitators [31, 49, 65, 73, 80, 81]. Specifically, services that permitted a non-clinical and comfortable environment were deemed as important aspatial factors for young people [61, 73]. Co-located services were also considered important for access, as this allows service integration and facilitated information sharing [31, 41, 63].

Community supports. The community was considered to be an important aspatial facilitator. This included healthcare providers being involved and connected with the community [56, 65, 66], as well as having a sense of community [59], as a way to facilitate care via information sharing, collaboration, and knowing community members and local issues. For the service user, community and place was seen as a source of strength as noted by one study [39].

Facilitators affecting service users

Mental health literacy. Several studies reported that having awareness of mental health issues and being confident in using services were aspatial facilitators to mental health service access and utilisation [52, 57, 59, 66, 70]. These factors are generally referred to as mental health literacy within the wider literature, which is a crucial component of healthcare [84].

Culturally-sensitive practice. Of the studies that reported on cultural elements of mental health service provision, it was noted that Indigenous and other culturally appropriate staff (i.e., a Koori Mental Health Liaison Officer or Aboriginal Mental Health Worker), as well as the involvement of Community Elders and spiritual healers [48] assisted with service access and utilisation [48, 66]. Further, culturally appropriate décor and flexibility in meeting places [66], and the use of culturally acceptable models of mental health [48] were also seen as important aspatial dimensions.

Geographical analysis

Overall, thirty studies were described as being relevant to rural areas [18, 31, 33,34,35,36, 38, 39, 42, 43, 48,49,50, 53, 57, 58, 61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70, 73, 76, 78, 83], three studies were pertinent to regional areas [39, 56, 79], two studies were concerned with remote areas [77, 81], and the remaining studies involved combinations of regional/rural/remote populations of Australia [37, 40, 41, 44,45,46,47, 51, 52, 54, 55, 59, 60, 71, 74, 75, 80, 82]. Over one third of the studies (n = 21, 39.6%) reported or provided specific spatial data, which allowed the MMM [4] to be applied directly to the study location; n = 10 (47.6%) of these studies included multiple locations, resulting in a total of 41 MMM categories. Studies were conducted most frequently in MM5 small rural towns (n = 10, 24.4%) and MM3 large rural towns (n = 9, 22.0%) and least frequently in MM6 remote communities (n = 3, 7.3%). The first author’s location was used as a proxy location for 28 studies (52.8%). Of these studies, the most frequent location was MM1 metropolitan settings (n = 16, 57.1%), likely due to the high proportion of study locations being taken from the first author’s location, and that many universities and research centres are located in major cities. There were no studies conducted in MM5 small rural towns (n = 0, 0%). Three author locations (5.7%) could not be determined due to limited information provided. Table 4 displays details of the MMM categories according to spatial data reported or obtained and proxy locations. Due to the heterogeneity and lack of mutual exclusivity of the data, an analysis of the association between geographical area and specific barriers and facilitators was unable to be completed.

Discussion and implications

This scoping review identified the barriers and facilitators experienced by healthcare providers delivering mental health services and individuals accessing, or attempting to access mental health services in rural Australia. Prominent barriers included: limited resources; system complexity and navigation; attitudinal and social matters; technological limitations; distance to services; insufficient culturally-sensitive practice; and lack of awareness. Facilitators included person-centred and collaborative care; technological facilitation; environment and ease of access; community supports; mental health literacy and culturally-sensitive practice. We also aimed to understand these barriers and facilitators in relation to their geographical context; however, the variability in the data precluded the geographical analysis from being completed.

This study revealed a paucity of research conducted in MM6 remote and MM7 very remote communities in Australia when specific spatial data are considered, as well as in the ACT — however, it is noted that the majority of the ACT is classified as metropolitan, with 99.83% (387,887 residents) of the population residing in MM1 at the time of the 2016 census [2]. Moreover, when proxy study locations are used, many studies are conducted by researchers located in metropolitan areas. Only three studies specifically included service users who were under the age of 18 years old, representing a significant gap in understanding the mental health service needs of the younger population. Although it is acknowledged that there are considerable research ethics restrictions in place to protect children and young people, the onset of many mental health issues tends to occur between 14.5 and 18 years of age [85], highlighting the importance of understanding barriers and facilitators to accessing mental health services amongst the younger cohort. Due to the heterogeneity of the findings, the following discussion considers the most prominent barriers and facilitator concepts identified across the studies.

Review findings support limited resources as being one of the biggest restrictors of mental health service access and utilisation within rural Australia. Thes findings echo reports at the national scale, which show the mental health workforce is heavily concentrated in metropolitan areas compared to other remoteness areas, relative to the population [86]. Considerable efforts need to be made to reduce the resource inequalities, including the dearth of mental health professionals practicing outside of metropolitan cities. Recently, the National Mental Health Workforce Strategy Taskforce (the Strategy) was established to deliberate the quality, supply, distribution, structure, and methods to improve attracting, training, and retaining Australia’s mental health workforce [87]. The Consultation Draft of the Strategy highlights six objectives, including (1) careers in mental health are recognised as, attractive; (2) data underpins workforce planning; (3) the entire mental health workforce is utilised; (4) the mental health workforce is appropriately skilled; (5) the mental health workforce is retained in the sector; and (6) the mental health workforce is distributed to deliver support and treatment when and where consumers need it [88]. These objectives reflect the systemic resource issues cited in the current scoping review and emphasise the importance of a contemporary approach to increasing resources for mental health services in rural Australia. This contemporary approach is important, as it has previously been acknowledged that increasing graduates has not resolved workforce maldistribution in other areas of healthcare (i.e., medical physicians), but rather, an improved distribution of both human and other resources is needed [89, 90].

For the service user, resource issues spanned both aspatial and spatial dimensions and include the affordability (i.e., perceived worth relative to cost) and accessibility of the service (i.e., the location of the service and ease of getting to that location) [12, 13]. Transport issues were commonly reported to be a resource issue within the current review and the wider literature. Limited transport compounds access issues for specific subpopulations, such the elderly, particularly when they do not have personal transport and when there is no public transport available [50]. This issue is likely compounded by resource limitations, including the cost of travel, and is specifically related to spatial distance to services. Distance to services is a significant barrier to accessing healthcare. Wood et al. [91] in a systematic review, identified that there is a lack of research which measures spatial access specific to mental health services in Australia, and highlighted a need for consensus on what is reasonable access to healthcare services. Further, reports have noted that while distance alone is a significant barrier to accessing healthcare, accommodation may sometimes need to be sought depending on the time of the appointment, adding to the cost of attending the appointment [92] and further perpetuating the resource issues experienced by those living in rural areas of Australia. In addition, although not specifically reported in the current review, it is likely that the time required for traveling to and attending such appointments may require the individual to choose between tending to work or family needs or receiving the help needed.

Transport and other resource issues, as well as distance to services, may be mitigated through telehealth appointments, which have been central to the provision of healthcare since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the utilisation of telehealth requires many patients to have had a face-to-face consultation with their GP in the previous 12 months [93], which may preclude some Australians from rural areas from its use, considering the significant workforce maldistribution previously discussed. Moreover, rural areas of Australia also experience digital disadvantage as a result of lower internet connectivity — brought about by the high costs of installing internet infrastructure in rural and remote areas — and the socio-economic disadvantage experienced by those who live outside of metropolitan areas [94]. These issues are compounded by an ageing population, lower educational levels, a larger primary industry sector, a higher unemployment rate, and a higher Indigenous population in rural and remote Australia [94]. High cost, connectivity issues, and suitability for specific client groups should be key considerations in the delivery of technology-based mental health services. Notwithstanding these issues, the current review identified that technology-based services may be a useful adjunct to physical services, particularly in relation to reducing the need to travel, consultation immediacy, and clinician upskilling. This finding partially supports a recent systematic review, which found that youth located in rural and remote areas of Australia and Canada prefer to see mental health professionals in person, with telehealth provided as an additional option [95]. As such, the benefits and limitations to technology-based mental health services needs to be carefully considered by those designing services.

A key barrier to both access and utilisation in the current review was the complexity of using and navigating the mental health system. These issues typically occur at the system and organisation level and affect the way a service operates and its culture, making it challenging for service users to receive effective care. A complex mental health system and service fragmentation has been previously reported to lead to confusion and a lengthy amount time spent trying to navigate the system, with these issues being even greater amongst those who are younger, less autonomous, or who have less experience navigating the system [96]. System navigation initiatives may address this gap and have previously been implemented via the Partners in Recovery (PIR) program — established to facilitate care coordination for people with severe and persistent mental illness — with positive impacts for those who used the program [97]. However, the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme has superseded the PIR program, and has rendered many former PIR program participants ineligible for support [98, 99], representing a significant gap in mental health service navigation and care coordination support. Isaacs et al. [100], identified that it is more cost effective to support people with severe and persistent mental illness to access PIR supports than to not provide this support, due to the potential increased need for other services (e.g., hospital admissions, homelessness supports, residential supports). Indeed, the Australian Government’s Productivity Commission (Productivity Commission) recommended that life insurers should have greater flexibility to fund approved mental health services to reduce the likelihood of hospitalisation for mental health issues [101]. In addition, Isaacs et al. [100] reported that co-located services — which were reported as a facilitator in the current review — and the increased need of non-clinical support through mental health community support services, offered via non-governmental and not-for-profit organisations, were demonstrated to be important considerations for cost effective mental health care.

Attitudinal or social matters are frequently reported to be key barriers for rural Australians to accessing care and are considered to be an aspatial dimension [12, 13]. These matters which include stigma, fear of judgement, stoicism, lack of trust, preference for keeping to oneself, and reluctance to seek help have been reported on the global scale as impacting upon help-seeking in rural areas in relation to rural identity [22]. Stoicism, in particular, is ordinarily viewed as a positive trait, with rural participants of a global review contextualising stoicism as an inflexible element to their core identity, however, this trait has repeatedly been reported as a barrier to the uptake of mental health services in this review [45, 50, 67, 70] and in the wider literature [22]. In terms of addressing attitudinal and social matters, previous Australian research [16] has identified that intentions to seek help for a mental or emotional issue decreased with a higher classification of remoteness. Moreover, stoicism and attitudes towards seeking professional help were predictive of help-seeking intentions for participants from both rural and metropolitan areas, but sex, suicidality, and previous engagement with a mental health professional were additionally predictive of help-seeking intentions for rural Australians [16]. The current scoping review identified few studies that specifically reported on these issues in relation to barriers to accessing services [37, 55, 68, 70], suggesting a need to increase research focus on these issues. Interestingly, Kaukiainen and Kõlves [16] study, found that attitudes towards seeking professional help mediated the relationship between stoicism and help-seeking intentions for participants from both rural and metropolitan locations, suggesting that attitudes towards seeking professional help may be a fruitful avenue to target to increase help-seeking intentions for all Australians [16]. Education programs delivered in secondary school or tertiary settings have been suggested as a way to improve attitudes towards help-seeking and stigma [102]. These avenues may also be useful to increase mental health literacy (i.e., the public knowledge and recognition of mental disorders and knowing where and how to seek help) [84] in the community, given that lack of awareness was a barrier and mental health literacy was a facilitator in the current review.

Providing person-centred and collaborative care was reported as a key facilitator in the current review. Person-centred care is generally defined as care that is holistic and incorporates the person’s context, individual expression, beliefs, and preferences, and includes families and caregivers, as well as prevention and promotion activities [103]. Indeed, person-centred care is a prominent practice model in mental health care, and this model of care may be particularly beneficial in rural Australia, given that it aims to decrease barriers between health service providers via shared knowledge. This model of care is collaborative by nature, although it should be noted that collaborative care is a distinct, though related model of care. Collaborative care refers to health professionals and patients working together to overcome a mental health problem [104]. This model of care has been shown to improve depression and anxiety outcomes across the short to long term (i.e., 0–24 months), and has benefits on medication use, patient satisfaction, and mental health quality of life [104]. The Productivity Commission recommended the trial of innovation funds to diffuse best practice in mental health service delivery and to eliminate practices that are no longer supported by evidence [101]. Such innovation funds may allow healthcare providers to maintain currency on practices such as person-centred and collaborative care. Importantly, the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System (the Royal Commission) [90] identified person-centred care as a way to promote inclusion and prevent inequalities, and was specifically linked to providing culturally safe mental health care — which was noted as a facilitator to access and utilisation in the current review and has been highlighted as an important approach to eliminate health inequalities [105]. Moreover, the Royal Commission recommended the use of an integrated service approach — where service providers can work together to provide care [90]. This approach to care may mitigate service fragmentation and system complexity and navigation barriers, and also permit environments that are comfortable and allow ease of use — as identified as facilitators in the current review.

Community support, both in the sense of individuals feeling connected to the community and healthcare providers being seen within the community, was a key concept in the current review. For the service user, Johnson et al. [39] reported that accessing services under the scrutiny of the community was seen as a challenge, but that the community was also seen a source of strength. Crotty et al. [56] noted the duality for healthcare providers being involved with the community in both a social and professional sense, leading to both challenges and a feeling of togetherness. This sense of togetherness reflects the historical view that rural and remote communities have been connected over several generations [106]. Notably, in the current review, one study on healthcare provider perspectives on workforce retention reported that personal connections and a ‘natural’ connection to the community were key factors in the decision for staff working in remote areas to stay [33], suggesting the importance of embedded relationships in this setting. Preferences to stay in rural and remote towns have been associated with a sense of belonging and the quality of diverse and interesting activities, particularly for younger people [107], and these factors should be strengthened to permit the retention of the rural mental health workforce.

It is noteworthy that many of the studies were undertaken at metropolitan locations, suggesting that much of the research completed on rural locations was not necessarily conducted within this setting. However, it is acknowledged that many university locations are affiliated with major campuses, which are often located in metropolitan areas. Simultaneously, many rurally-based health and community services do not have the resources to undertake locally-generated research, and this consequently limits the evidence available for policymakers to make informed decisions regarding the health of the rural population — noting that place-based approaches are gaining traction [108,109,110]. This area is a key focus of the RHMT program [111]. The RHMT program aims to maximise investment in of Australia via academic networks, developing an evidence-base, and providing training in rural areas for health professionals. To date the RHMT program has seen that health graduates who undertook clinical placements in the most rural settings are working more in rural locations [112], and this is likely to have flow-on effects for healthcare providers to build connections to these areas, retain the workforce, and increase health outcomes for the community.

This review highlights the need for a contemporary approach to mental health services in rural Australia. This includes encouraging and educating the public about mental health issues and how to seek and engage in timely mental health care that is appropriate to one’s needs. Simultaneously, this review suggests a need to reconsider how the public navigates mental health services, and to redesign services that are easy to engage with, culturally safe, comfortable to use, and have technological capabilities. This may be more accurately achieved when services are designed with local issues and the community in mind via the integration of bottom-up place-based strategies and top-down place-sensitive approaches, particularly given that a one-size-fits-all approach to policy — and thus mental health service design — does not favour regions and localities [113]. It is critical that rural mental health services are invested in to remove barriers and improve health equity. The fiscal implications of such investment may be offset using this integrated approach, which leverages local and external assets, encourages workforce retention, and may reduce costs in other areas healthcare service delivery.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this scoping review include the use of peer-reviewed and grey literature, the full-span of the child-adult age range, and the wide variety of included studies. In addition, this scoping review applied a consistent approach to applying remoteness categories, albeit this application was not without issues. For example, Wand et al. [40] and Wand et al. [41] reports on work done in Maitland (MM1) and Dubbo (MM3). Maitland (NSW) is of particular interest in the context of remoteness settings as it has historically been described as a regional area. In the early 2000s when the Australian Bureau of Statistics was defining the most accessible category of the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA), Maitland (as well as other locations such as Wollongong, NSW and Geelong, Victoria) was included in the most accessible category [114].

Several limitations must also be considered. Firstly, many sources — particularly grey literature sources — included potentially relevant information; however, a lack of clear evidence that the data specifically pertained to those living in regional/rural/remote areas prevented many of these sources from being included. In addition, findings were limited by the available literature, especially among community service organisations, which have limited resources to generate research outputs. The search strategy was limited to 2012–2022 and did not include search terms specific to certain subgroups of the population who have been known to experience barriers to mental health services in rural areas (e.g., farmers and people from CALD backgrounds), and some search results may have been omitted as a result of this. It was not possible to discern whether findings related specifically to access or utilisation in many studies, and as such, a nuanced discussion of these dimensions is not provided. Further, the data were heterogeneous and results tended to be grouped across regional, rural, and/or remote contexts, precluding an analysis of the association between geographical area and barriers and facilitators from taking place. Future research may consider completing a comprehensive geographical analysis once additional data on the topic becomes available. Lastly, although data screening was completed by two reviewers, only one reviewer coded the extracted data into key concepts, and this may have introduced bias into the results, however the key concepts were agreed upon by the research team.

Conclusion

This scoping review found a number of barriers to accessing and utilising mental health services that may be overcome through initiatives that have been implemented or suggested by the government. Importantly, many of the spatial barriers associated with access and utilisation may be mitigated through innovative solutions, such as a combination of face-to-face and technology-based service provision, provided that careful consideration is given to the technological and resource limitations seen in the rural context of Australia. Parallel with this, several facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services were noted, some of which may already be prominent in the provision of services, but could be further strengthened through additional training, service re-design, and community initiatives.

The included studies varied in their aim, setting, and study design, and many studies were grouped across MMM categories, disallowing a nuanced understanding of how barriers and facilitators operate within specific geographical contexts. This, paired with the finding that many studies were conducted at a metropolitan location, highlights the importance of conducting research within the rural setting. Additional research generated from rural areas, as well as consideration for how remoteness is measured, would assist in providing a more comprehensive understanding of the barriers and facilitators to mental health services within the geographic contexts they occur.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Australian Capital Territory

- ARIA:

-

Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia

- CALD:

-

Culturally and linguistically diverse

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- FTE:

-

Full time equivalent

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- LGBTIQA +:

-

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer/questioning, asexual

- MMM:

-

Modified Monash Model

- PCC:

-

Population/concept/context

- PHN:

-

Primary Health Network

- PIR:

-

Partners in Recovery

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- NT:

-

Northern Territory

- QLD:

-

Queensland

- RHMT:

-

Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training

- SA:

-

South Australia

- TAS:

-

Tasmania

- UCC:

-

Urgent care centre

- VIC:

-

Victoria

- WA:

-

Western Australia

5 References

Inder KJ, Berry H, Kelly BJ. Using cohort studies to investigate rural and remote mental health. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(4):171–8.

Versace VL, Skinner TC, Bourke L, Harvey P, Barnett T. National analysis of the modified Monash Model, population distribution and a socio-economic index to inform rural health workforce planning. Aust J Rural Health. 2021;29(5):801–10.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mental health workforce 2023 [Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/topic-areas/workforce].

Australian Department of Health. Modified Monash Model 2019 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/modified-monash-model-fact-sheetaccess].

Australian Government. Deaths by suicide by remoteness areas. In: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, editor.; 2021.

Rost K, Fortney J, Fischer E, Smith J. Use, quality, and outcomes of care for mental health: the rural perspective. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59(3):231–65.

Fitzpatrick SJ, Perkins D, Luland T, Brown D, Corvan E. The effect of context in rural mental health care: understanding integrated services in a small town. Health Place. 2017;45:70–6.

Francis K. Health and health practice in rural Australia: where are we, where to from here? Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2012;5(1):28–36.

Fuller J, Edwards J, Martinez L, Edwards B, Reid K. Collaboration and local networks for rural and remote primary mental healthcare in South Australia. Health Soc Care Commun. 2004;12(1):75–84.

Russell DJ, Humphreys JS, Ward B, Chisholm M, Buykx P, McGrail M, et al. Helping policy-makers address rural health access problems. Aust J Rural Health. 2013;21(2):61–71.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health workforce 2023 [Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/workforce/health-workforce#rural].

Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–40.

Khan AA. An integrated approach to measuring potential spatial access to health care services. Socio-Economic Plann Sci. 1992;26(4):275–87.

Bourke L, Humphreys JS, Wakerman J, Taylor J. Understanding rural and remote health: a framework for analysis in Australia. Health Place. 2012;18(3):496–503.

Saurman E. Improving access: modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s theory of access. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2016;21(1):36–9.

Kaukiainen A, Kõlves K. Too tough to ask for help? Stoicism and attitudes to mental health professionals in rural Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2020;20(2):5399.

Catherine C, Myfanwy M, Rafat H. Work challenges negatively affecting the job satisfaction of early career community mental health professionals working in rural Australia: findings from a qualitative study. J Mental Health Train Educ Pract. 2018;13(3):173–86.

Cosgrave C, Maple M, Hussain R. Work challenges negatively affecting the job satisfaction of early career community mental health professionals working in rural Australia: findings from a qualitative study. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice; 2018.

Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):18.

Liu C, Watts B, Litaker D. Access to and utilization of healthcare: the provider’s role. Expert Rev PharmacoEcon Outcomes Res. 2006;6(6):653–60.

Aisbett D, Boyd CP, Francis KJ, Newnham K. Understanding barriers to mental health service utilization for adolescents in rural Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2007;7(1):1–10.

Cheesmond NE, Davies K, Inder KJ. Exploring the role of rurality and rural identity in mental health help-seeking behavior: a systematic qualitative review. J Rural Mental Health. 2019;43(1):45–59.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Kavanagh B, Beks H, Versace V, Quirk S, Williams L. Exploring the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services in regional, rural, and remote Australia: a scoping review protocol. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12).

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Health workforce locator 2022 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/apps-and-tools/health-workforce-locator].

Versace VL, Beks H, Charles J. Towards consistent geographic reporting of australian health research. Med J Australia. 2021;215(11):525.

Beks H, Walsh S, Alston L, Jones M, Smith T, Maybery D et al. Approaches used to describe, measure, and analyze place of practice in Dentistry, Medical, nursing, and Allied Health Rural Graduate Workforce Research in Australia: a systematic scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2022; 19(3).

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software, Melbourne, Australia [Available from: www.covidence.org.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Barraclough F, Longman J, Barclay L. Integration in a nurse practitioner-led mental health service in rural Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2016;24(2):144–50.

Cosgrave C, Maple M, Hussain R. Work challenges negatively affecting the job satisfaction of early career community mental health professionals working in rural Australia: findings from a qualitative study. J Mental Health Train Educ Pract. 2018;13(3):173–86.

Cosgrave C, Hussain R, Maple M. Retention challenge facing Australia’s rural community mental health services: service managers’ perspectives. Austr J Rural Health. 2015;23(5):272–6.

De Silva T, Prakash A, Yarlagadda S, Johns MD, Sandy K, Hansen V et al. General practitioners’ experiences and perceptions of mild moderate depression management and factors influencing effective service delivery in rural Australian communities: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2017;11(1).

Dunstan DA, Todd AK, Kennedy LM, Anderson DL. Impact and outcomes of a rural personal helpers and mentors service. Aust J Rural Health. 2014;22(2):50–5.

Evans J, Horn K, Cowan D, Brunero S. Development of a clinical pathway for screening and integrated care of eating disorders in a rural substance use treatment setting. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(5):878–87.

Handley TE, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Inder KJ, Lewin TJ, Attia JR, Fuller J et al. Self-reported contacts for mental health problems by rural residents: predicted service needs, facilitators and barriers. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14.

Hussain R, Guppy M, Robertson S, Temple E. Physical and mental health perspectives of first year undergraduate rural university students. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:848.

Johnson S, Brough M, Darracott R. Unmasking depression: challenging structural oppression whilst recognising individual agency. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice. 2021;20(3):738–54.

Wand T, Collett G, Cutten A, Buchanan-Hagen S, Stack A, White K. Patient and staff experience with a new model of emergency department based mental health nursing care implemented in two rural settings. Int Emerg Nurs. 2021;57:N.PAG-N.PAG.

Wand T, Collett G, Keep J, Cutten A, Stack A, White K. Mental health nurses’ experiences of working in the emergency department of two rural australian settings. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2021.

Weber M, Davis K. Food for thought: enabling and constraining factors for effective rural eating disorder service delivery. Aust J Rural Health. 2012;20(4):208–12.

Wilson RL, Cruickshank M, Lea J. Experiences of families who help young rural men with emergent mental health problems in a rural community in New South Wales, Australia. Contemp Nurse. 2012;42(2):167–77.

Batterham PJ, Kazan D, Banfield M, Brown K. Differences in mental health service use between urban and rural areas of Australia. Australian Psychol. 2020;55(4):327–35.

Clough BA, March S, Leane S, Ireland MJ. What prevents doctors from seeking help for stress and burnout? A mixed-methods investigation among metropolitan and regional-based australian doctors. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(3):418–32.

Duggan M, Harris B, Chislett W-K, Calder R. Nowhere else to go: Why Australia’s health system results in people with mental illness getting ‘stuck’in emergency departments. 2020.

Hays C, Sparrow M, Taylor S, Lindsay D, Glass B. Pharmacists’ full scope of practice: knowledge, attitudes and practices of rural and remote australian pharmacists. J Multidisciplinary Healthc. 2020;13:1781–9.

Mirza T. First Australians deserve first-class psychiatric care: towards a better sociocultural understanding. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019;53:66.

Mollah TN, Antoniades J, Lafeer FI, Brijnath B. How do mental health practitioners operationalise cultural competency in everyday practice? A qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):480.

Muir-Cochrane E, O’Kane D, Barkway P, Oster C, Fuller J. Service provision for older people with mental health problems in a rural area of Australia. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(6):759–66.

Bowman S, Nic Giolla Easpaig B, Fox R. Virtually caring: a qualitative study of internet-based mental health services for LGBT young adults in rural Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2020;20(1):5448.

Butterfly Foundation. Maydays 2020 survey report: Barriers to accessing eating disorder healthcare & support. 2020. Available from: https://butterfly.org.au/get-involved/campaigns/maydays/

Mental Health Council of Tasmania. Submission to the Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee inquiry into accessibility and quality of mental health serices in rural and remote Australia. 2018.

National Rural Health Alliance. Mental health in rural and remote Australia. National Rural Health Alliance; 2017.

Black G, Roberts RM, Li-Leng T. Depression in rural adolescents: relationships with gender and availability of mental health services. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12(3):2092.

Crotty MM, Henderson J, Fuller JD. Helping and hindering: perceptions of enablers and barriers to collaboration within a rural South australian mental health network. Aust J Rural Health. 2012;20(4):213–8.

Dawson S, Gerace A, Muir-Cochrane E, O’Kane D, Henderson J, Lawn S, et al. Accessing mental health services for older people in rural South Australia. Australian Nurs Midwifery J. 2016;23(7):50.

Henderson J, Crotty MM, Fuller J, Martinez L. Meeting unmet needs? The role of a rural mental health service for older people. Adv Mental Health. 2014;12(3):182–91.

Henderson J, Dawson S, Fuller J, O’Kane D, Gerace A, Oster C, et al. Regional responses to the challenge of delivering integrated care to older people with mental health problems in rural Australia. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(8):1025–31.

Newman L, Bidargaddi N, Schrader G. Service providers’ experiences of using a telehealth network 12 months after digitisation of a large australian rural mental health service. Int J Med Informatics. 2016;94:8–20.

Orlowski S, Lawn S, Antezana G, Venning A, Winsall M, Bidargaddi N, et al. A rural youth consumer perspective of technology to enhance face-to-face mental health services. J Child Fam stud. 2016;25(10):3066–75.

Orlowski S, Lawn S, Matthews B, Venning A, Wyld K, Jones G, et al. The promise and the reality: a mental health workforce perspective on technology-enhanced youth mental health service delivery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:562.

Orlowski S, Lawn S, Matthews B, Venning A, Jones G, Winsall M, et al. People, processes, and systems: an observational study of the role of technology in rural youth mental health services. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2017;26(3):259–72.

Procter N, Ferguson M, Backhouse J, Cother I, Jackson A, Murison J, et al. Face to face, person to person: skills and attributes deployed by rural mental health clinicians when engaging with consumers. Aust J Rural Health. 2015;23(6):352–8.

Beks H, Healey C, Schlicht KG. When you’re it’: a qualitative study exploring the rural nurse experience of managing acute mental health presentations. Rural & Remote Health. 2018;18(3):1–11.

Isaacs AN, Maybery D, Gruis H. Mental health services for aboriginal men: mismatches and solutions. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2012;21(5):400–8.

Isaacs AN, Maybery D, Gruis H. Help seeking by Aboriginal men who are mentally unwell: a pilot study. Early Intervent Psychiatry. 2013;7(4):407–13.

Isaacs AN, Sutton K, Hearn S, Wanganeen G, Dudgeon P. Health workers’ views of help seeking and suicide among Aboriginal people in rural Victoria. Aust J Rural Health. 2017;25(3):169–74.

Kidd T, Kenny A, Meehan-Andrews T. The experience of general nurses in rural australian emergency departments. Nurse Educ Pract. 2012;12(1):11–5.

Trail K, Oliffe JL, Patel D, Robinson J, King K, Armstrong G, et al. Promoting healthier masculinities as a suicide Prevention intervention in a Regional Australian Community: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives. Front Sociol. 2021;6:728170.

Byrne L, Happell B, Reid-Searl K. Acknowledging rural disadvantage in Mental Health: views of peer workers. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2017;53(4):259–65.

Knight D, Plumb T, Gorey C. A STARR is born! A shining example of Integrated Care. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18:1–2.

Malatzky C, Bourke L, Farmer J. I think we’re getting a bit clinical here’: a qualitative study of professionals’ experiences of providing mental healthcare to young people within an australian rural service. Health & Social Care in the Community; 2020.

Onnis L-A, Kinchin I, Pryce J, Ennals P, Petrucci J, Tsey K. Evaluating the implementation of a Mental Health Referral Service connect to Wellbeing: a Quality Improvement Approach. Front Public Health. 2020;8:585933.

Taylor M, Kikkawa N, Hoehn E, Haydon H, Neuhaus M, Smith AC, et al. The importance of external clinical facilitation for a perinatal and infant telemental health service. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(9):566–71.

Richardson L, Reid C, Dziurawiec S. Going the extra mile’: satisfaction and alliance findings from an evaluation of videoconferencing telepsychology in rural western Australia. Australian Psychol. 2015;50(4):252–8.

Salinas-Perez JA, Gutierrez-Colosia MR, Furst MA, Suontausta P, Bertrand J, Almeda N, et al. Patterns of mental health care in remote areas: Kimberley (Australia), Nunavik (Canada), and Lapland (Finland). Can J Psychiatry / La Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2020;65(10):721–30.

Consumers of Mental Health WA. Accessibility and quality of mental health services in rural and remote Australia Submission 31. 2018. Available from: https://comhwa.org.au/resources-publications

Bridgman H, Ashby M, Sargent C, Marsh P, Barnett T. Implementing an outreach headspace mental health service to increase access for disadvantaged and rural youth in Southern Tasmania. Aust J Rural Health. 2019;27(5):444–7.

Reynish TD, Hoang H, Bridgman H, Nic Giolla Easpaig B. Mental health and related service use by sex workers in rural and remote Australia: ‘there’s a lot of stigma in society’. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2021:1–16.

Hinton R, Kavanagh DJ, Barclay L, Chenhall R, Nagel T. Developing a best practice pathway to support improvements in indigenous Australians’ mental health and well-being: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8).

Ellem K, Baidawi S, Dowse L, Smith L. Services to young people with complex support needs in rural and regional Australia: beyond a metro-centric response. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;99:97–106.

van Spijker BA, Salinas-Perez JA, Mendoza J, Bell T, Bagheri N, Furst MA, et al. Service availability and capacity in rural mental health in Australia: Analysing gaps using an integrated mental health atlas. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019;53(10):1000–12.

Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am Psychol. 2012;67(3):231.

Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, Croce E, Soardo L, Salazar de Pablo G, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):281–95.

Australian Government Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mental health services in Australia 2022 [Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/mental-health-workforce].

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National Mental Health Workforce Strategy Taskforce 2021 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/committees-and-groups/national-mental-health-workforce-strategy-taskforce].

ACIL Allen. National Mental Health Workforce Strategy consultation draft. 2021. Available from: https://acilallen.com.au/uploads/media/NMHWS-ConsultationDraftStrategy-040821-1628234534.pdf

May JA, Scott A. The road less travelled: supporting physicians to practice rurally. Med J Aust. 2021;215(1):29–30.

State of Victoria. Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System. 2021.

Wood SM, Alston L, Beks H, Mc Namara K, Coffee NT, Clark RA, et al. The application of spatial measures to analyse health service accessibility in Australia: a systematic review and recommendations for future practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):330.

Mental Health Council of Tasmania. Submission to Legislative Council Inquiry into Rural Health Services: Access to timely and appropriate mental health care in rural and remote Tasmanian communities. 2021.

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Providing health care remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic 2022 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/health-alerts/covid-19/coronavirus-covid-19-advice-for-the-health-and-disability-sector/providing-health-care-remotely-during-the-covid-19-pandemic].

Park S. Digital inequalities in rural Australia: a double jeopardy of remoteness and social exclusion. J Rural Stud. 2017;54:399–407.

Mseke EP, Jessup B, Barnett T. A systematic review of the preferences of rural and remote youth for mental health service access: Telehealth versus face-to‐face consultation. Aust J Rural Health. 2023.

Robards F, Kang M, Steinbeck K, Hawke C, Jan S, Sanci L, et al. Health care equity and access for marginalised young people: a longitudinal qualitative study exploring health system navigation in Australia. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):41.

Stewart V, Slattery M, Roennfeldt H, Wheeler AJ. Partners in recovery: paving the way for the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(3):208–15.

Consortia HaLMMPiR. Submission to the joint standing committee on the NDIS: The provision of services under the NDIS for people with psychosocial disabilities related to mental health conditions. Joint submisson by the Hume and Loddon Mallee Murray Partners in Recovery Consortia. 2017.

Hancock N, Smith-Merry J, Gillespie JA, Yen I. Is the Partners in Recovery program connecting with the intended population of people living with severe and persistent mental illness? What are their prioritised needs? Aust Health Rev. 2016;41(5):566–72.

Isaacs AN, Dalziel K, Sutton K, Maybery D. Referral patterns and implementation costs of the Partners in Recovery initiative in Gippsland: learnings for the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Australasian Psychiatry. 2018;26(6):586–9.

Productivity Commission. 5-year Productivity Inquiry: Advancing Prosperity. Canberra., ; 2023. Contract No.: Inquiry Report no. 100. Available from: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity/report

Mehta N, Clement S, Marcus E, Stona A-C, Bezborodovs N, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(5):377–84.

Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, Zelinsky S, Quan H, Lu M. How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2018;21(2):429–40.

Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012(10).

Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Loring B, Paine S-J, et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):174.

Wainer J, Chesters J. Rural mental health: neither romanticism nor despair. Aust J Rural Health. 2000;8(3):141–7.

Pretty GH, Chipuer HM, Bramston P. Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural australian towns: the discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. J Environ Psychol. 2003;23(3):273–87.

Alston L, Bourke L, Nichols M, Allender S. Responsibility for evidence-based policy in cardiovascular disease in rural communities: implications for persistent rural health inequalities. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44(4):527–34.

Alston L, Versace VL. Place-based research in small rural hospitals: an overlooked opportunity for action to reduce health inequities in Australia? Lancet Reg Health–Western Pac. 2023;30.

Alston L, Field M, Brew F, Payne W, Aras D, Versace VL. Addressing the lack of research in rural communities through building rural health service research: establishment of a research unit in Colac, a medium rural town. Aust J Rural Health. 2022;30(4):536.

Walsh S, Lyle DM, Thompson SC, Versace V, Browne LJ, Knight S et al. The role of national policies to address rural allied health, nursing and dentistry workforce maldistribution. 2020.

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) program 2022 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/rhmt].

Sotarauta M. Place-based policy, place sensitivity and place leadership. Working paper 46/2020: Tampere University; 2020.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. ABS views on remoteness 2001 2001 [Available from: https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/free.nsf/0/FCC8158C85424727CA256C0F000035 75/$File/12440_2001.pdf.

Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Christensen H, Carragher N, Sunderland M. Independent effects of mental disorders on suicidal behavior in the community. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2018;48(5):512–21.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Emergency department care 2017–18: Australian hospital statistics Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2018 [Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9ca4c770-3c3b-42fe-b071-3d758711c23a/aihw-hse-216.pdf.aspx?inline=true].

Mental Health Services Australia A. [Available from: https://mhsa.aihw.gov.au/services/medicare/].

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

BEK, HB, and VLV are funded by the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) program. LJW is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Fellowship [1174060].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BEK conceptualised the research question; completed the search, data screening, extraction, and analysis; and wrote the original draft of this manuscript. KBC contributed to data screening and extraction. HB and VLV assisted with the geographical analysis. All authors edited and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As this scoping review utilised published literature only, ethics approval and consent to participate was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12913_2023_10034_MOESM3_ESM.docx

Additional Table 3: Barriers and/or facilitators of access and/or utilisation factors in regional, rural, and remote Australia

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kavanagh, B.E., Corney, K.B., Beks, H. et al. A scoping review of the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising mental health services across regional, rural, and remote Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 1060 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10034-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10034-4