Abstract

Background

Pharmacist-led medication review and medication management programs (MMP) are well-known strategies to improve medication safety and effectiveness. If performed interprofessionally, outcomes might even improve. However, little is known about task sharing in interprofessional MMP, in which general practitioners (GPs) and community pharmacists (CPs) collaboratively perform medication reviews and continuously follow-up on patients with designated medical and pharmaceutical tasks, respectively. In 2016, ARMIN (Arzneimittelinitiative Sachsen-Thüringen) an interprofessional MMP was launched in two German federal states, Saxony and Thuringia. The aim of this study was to understand how GPs and CPs share tasks in MMP when reviewing the patients’ medication.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional postal survey among GPs and CPs who participated in the MMP. Participants were asked who completed which MMP tasks, e.g., checking drug-drug interactions, dosing, and side effects. In total, 15 MMP tasks were surveyed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “I complete this task alone” to “GP/CP completes this task alone”. The study was conducted between 11/2020 and 04/2021. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

In total, 114/165 (69.1%) GPs and 166/243 (68.3%) CPs returned a questionnaire. The majority of GPs and CPs reported (i) checking clinical parameters and medication overuse and underuse to be completed by GPs, (ii) checking storage conditions of drugs and initial compilation of the patient’s medication including brown bag review being mostly performed by CPs, and (iii) checking side-effects, non-adherence, and continuous updating of the medication list were carried out jointly. The responses differed most for problems with self-medication and adding and removing over-the-counter medicines from the medication list. In addition, the responses revealed that some MMP tasks were not sufficiently performed by either GPs or CPs.

Conclusions

Both GPs’ and CPs’ expertise are needed to perform MMP as comprehensively as possible. Future studies should explore how GPs and CPs can complement each other in MMP most efficiently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Medication reviews (MR) are a well-known strategy to improve medication safety and effectiveness. They can solve drug-related problems (DRP), improve medication appropriateness, and clinical outcomes [1, 2]. If good interprofessional collaboration is in place, MR might be implemented more efficiently [3]. Furthermore, interprofessional collaboration between general practitioners (GPs) and community pharmacists (CPs) has positive effects on blood pressure or HbA1cvalues [4,5,6,7,8,9], among others, and possibly on asthma patients [10]. In addition, the integration of CPs in primary care teams shows positive effects on LDL-cholesterol levels, and appropriate medication use [11].

Although interprofessionalism can improve patient care, regular involvement of both GPs and CPs in MR is rare [12]. Studies that have investigated interprofessional MR and medication management in primary care have often only addressed how GPs and CPs interact at an organizational level in the provision of a service [13, 14]. The intervention usually started with GPs sending their patients to the pharmacy for a MR. The pharmacy then performed the MR and forwarded recommendations for action to the GP [15, 16]. Prior studies usually investigated the attitude of GPs towards the conduct of MR by CPs, whether the pharmacists’ recommendations for action were implemented by GPs, or how the cooperation between GPs and CPs can be successfully designed [17,18,19,20,21]. In contrast, little research has been done on interprofessional collaboration in medication management which comprises continuous care of the patient in a multidisciplinary team following a MR. In particular, little is known about how medication management tasks, such as checking of drug-drug interactions, duplicate medications, or guideline-adherence are shared between GPs and CPs [22].

In Germany, an interprofessional medication management program (MMP) was introduced in 2016 and implemented by CPs working in community pharmacies and GPs as part of ARMIN (“Arzneimittelinitiative Sachsen-Thüringen”), a project endorsed by professional associations and a statutory health insurance (SHI) fund (AOK PLUS). ARMIN was implemented in two federal states, Saxony and Thuringia [23]. In the MMP, patients signing up for the program chose both a GP and a community pharmacy that jointly supervised the patients’ drug therapy. Specific tasks and responsibilities were assigned to each professional group. Participating GPs should take care of the medical aspects, including guideline-directed medical therapy, while participating CPs should take care of the pharmaceutical aspects, including instructions on the correct use of medicines. Other tasks under the MMP included the review of over-the-counter (OTC) medicines and continuous updating of the medication list [24]. Both GPs and CPs receive about EUR 100 for the medication review (one-time reimbursement) and about EUR 25 for a follow-up (up to every three months).

The aim of this study was to investigate how the MMP was implemented by GPs and CPs in routine clinical practice by analyzing who performed which tasks in the MMP. In addition, we examined how different GP-CP pairs carried out their task sharing i.e., whether tasks were carried out by both health care professionals (HCP) or by neither HCP, to gain insights into how well or even how diversely GPs and CPs coordinate task sharing in MMP.

Methods

Commissioned through the initiators of the ARMIN project, the study was conducted by the Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacoepidemiology at Heidelberg University Hospital together with the aQua Institute for Applied Quality Improvement and Research in Health Care (Göttingen, Germany). As part of the evaluation of the ARMIN project, participating GPs and CPs were pseudonymously surveyed about their experiences with the ARMIN project. The cross-sectional study was reported according to the Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS) [25] (see Additional file 1).

Until the beginning of 2020, 15.8% (243/1536) of the CPs and 3.9% (165/4178) of the GPs in the federal states of Saxony and Thuringia had registered for the MMP service and enrolled at least one patient in the MMP.

Questionnaire development

We developed a questionnaire that included nine sections: sociodemographic and general information, technology/software, implementation of the ARMIN program including MMP (see Additional file 2), impact of the ARMIN program on HCPs’ daily work, impact on non-ARMIN patients’ therapy and care, benefits, costs, cost–benefit ratio, and fulfillment of expectations and wishes. Response scales in the questionnaire mainly comprised Likert scales or single/multiple response options. The questionnaire was developed as a self-administered postal questionnaire. Organizations involved in the ARMIN project (see ARMIN study group) supported the questionnaire development.

If available, already validated questionnaires were used, such as two questionnaires to assess physician-pharmacist collaboration (ATCI; FICI) [26]. In addition, new sets of questions were developed for ARMIN MMP-specific workflows. The questionnaire was subjected to an internal quality assurance process to check comprehensibility, clarity, and unambiguity [27]. Then, it was piloted with GPs and CPs participating in ARMIN to ensure that the questionnaire is suitable for the target group. In the first round, five GPs and CPs each received the questionnaire via email or fax. All questions were piloted with the HCPs via videophone or phone using think-aloud and cognitive interviewing techniques. Adjustments, including the deletion of less relevant questions and the rewording of questions were iteratively incorporated into the questionnaire.

The survey procedure was tested in a second pilot round with five additional GPs and CPs each. The questionnaire was sent by regular mail, the participating HCPs filled in the questionnaires themselves, made comments on unclear questions and/or ambiguous answer options, and returned the questionnaire in a prepaid envelope. In a subsequent debriefing phone call, the HCPs’ comments were discussed and the adjustments made after the first round of piloting were reassessed. HCP considered the questionnaires to be easily understandable and clearly structured. As HCPs had no other important comments, the pilot phase was successfully completed.

Participants and recruitment

The target population of the survey, all GPs and CPs who participated in the MMP of at least one patient by September 1, 2020, was invited by the SHI fund to participate in the survey. Therefore, the AOK PLUS sent the questionnaire to 165 GPs and 243 CPs in November 2020. Concurrently, the Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians and the State Associations of Pharmacists informed their members about the survey in order to increase the response rate. A postal reminder was sent in December 2020 and an additional telephone reminder was issued at the end of January 2021. Both reminders were provided by the AOK PLUS and only sent to non-responders.

Data collection

The data collection took place between November 2020 and April 2021. Participants sent the questionnaire to the aQua Institute that extracted and digitized the responses using validated automatic data digitization systems. Then, aQua Institute sent the data sets to the Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacoepidemiology.

The data collection was pseudonymized by the SHI fund. Because only the SHI fund had access to the pseudonyms, aQua Institute and the Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacoepidemiology at the Heidelberg University Hospital collected de facto anonymous questionnaire data. Conversely, the SHI fund had no access to individual questionnaire data sets.

In this paper, we only report on the section “task sharing in the ARMIN MMP”. Participants were asked to rank task sharing for 15 MMP tasks with regard to the GP or CP with whom they supervised most of their patients. MMP tasks are: Initial compilation of the patient's medication including brown bag review, checking drug-drug interactions, duplicate medications, dosing, administration times, inadequate dosage forms, storage condition of drugs, side effects, non-adherence, problems regarding self-medication, clinical parameters, and medication overuse and underuse as well as explanation of and handing out the medication list, adding and removing OTC medicines from the medication list, and continuous updating of the medication list.

Data analyses

In a descriptive analysis, relative frequencies of GPs’ and CPs’ answers were calculated. Furthermore, to calculate mean Likert scores, Likert responses of GPs were coded as follows: “I complete this task alone” = 100%, “I complete this task with CP’s support” = 75%, “Equally” = 50%, “CP completes this task with my support” = 25%, or “CP completes this task alone” = 0%. Likert responses of CPs were coded in an analogous way: “I complete this task alone” = 100%, “I complete this task with GP’s support” = 75%, “Equally” = 50%, “GP completes this task with my support” = 25%, or “GP completes this task alone” = 0%.

In a sub-analysis, together with the SHI fund, we identified distinct GP-CP pairs who collaborated the most regarding the number of common patients in the MMP. These GP-CP pairs were identified in order to describe task sharing for distinct GP-CP pairs which were unambiguously identifiable. In contrast to the descriptive analysis, in which different perceptions of all GPs and CPs were analyzed, in this sub-analysis we aimed to identify MMP tasks that were insufficiently or sufficiently coordinated by distinct GP-CP pairs. The coordination of MMP tasks between both HCPs was operationalized by summing up the GPs’ and CPs’ part in performing each task. For example, if the CPs responded “GP completes this task with my support” (25%) and the corresponding GP responded “CP completes this task alone” (0%), a sum score would be 25% indicating that coordination for this task could be improved. Sum scores were analyzed using three categories, i.e., < 100%, = 100%, and > 100%. While a sum score of 100% could indicate a well-coordinated delivery of a task, a lower or higher sum score could be an indicator that coordination of collaboration within a GP-CP pair needs improvement.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R-Studio 1.4.1717 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used for data entry and analysis. Respondents with > 25% missing answers in the entire questionnaire and > 50% missing answers in the sections of interest for the planned analysis, i.e., the key section ‘task sharing in MMP’ and the key section ‘communication with the other HCPs’, were excluded from the analysis. Limits and key sections were discussed among the researchers. A combination of multiple criteria was found appropriate to exclude non-responders without eliminating to much data. Results were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Differences between GPs’ and CPs’ Likert responses were analyzed using Mann–Whitney-U test. The test was two-sided with an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Participants

Of 165 GPs and 243 CPs approached, 114 (response rate 69.1%) and 166 (68.3%) returned the questionnaire, respectively. Of these, 2/114 (1.8%) and 3/166 (1.8%) questionnaires were excluded due to incomplete responses. Ultimately, we included 112 (67.9%) questionnaires from GPs and 163 (67.1%) questionnaires from CPs in the descriptive analysis (Table 1).

Descriptive analysis of the perception of MMP tasks in the CP and GP population

Responses of GPs and CPs corresponded well for typically medical and pharmaceutical tasks: While GPs stated that they mainly complete (“I complete this task alone” and “I complete this task with CP’s support”) checking clinical parameters (n = 106, 94.7%), medication overuse and underuse (n = 91, 81.3%), and dosing (n = 83, 74.1%), CPs stated that tasks for which they mainly relied on GPs (“GP completes this task with my support” and “GP completes this task alone”) were checking clinical parameters (n = 144, 88.3%), medication overuse and underuse (n = 100, 61.3%), and dosing (n = 64, 39.3%). Conversely, CPs stated that tasks they mainly complete (“I complete this task alone” and “I complete this task with GP’s support”) are checking storage condition of drugs (n = 154, 94.5%), initial compilation of the patient’s medication (n = 148, 90.8%), and checking administration times (n = 118, 72.4%). GPs stated that tasks for which they mainly relied on CPs (“CP completes this task with my support” and “CP completes this task alone”) were checking storage condition of drugs (n = 84, 75.0%), initial compilation of patient’s medication (n = 61, 54.5%), and checking inadequate dosage form (n = 38, 33.9%).

On the other hand, HCPs see a shared responsibility for many MMP tasks. GPs most often responded “Equally” for drug-drug-interactions (n = 60, 53.6%), duplicate medication (n = 49, 43.8%), administration times (n = 36, 32.1%), inadequate dosage forms (n = 36, 32.1%), side effects (n = 49, 43.8%), non-adherence (n = 35, 31.3%), problems regarding self-medication (n = 37, 33.0%), adding and removing OTC medicines from the medication list (n = 44, 39.3%), and continuous updating of the medication list (n = 46, 41.1%). CPs most often responded “Equally” for dosing (n = 46, 28.2%), side effects (n = 61, 37.4%), non-adherence (n = 52, 31.9%), explanation of and handing out the medication list (n = 55, 33.7%), and continuous updating of the medication list (n = 82, 50.3%). Likert responses from GPs and CPs for all MMP tasks are shown in Table 2.

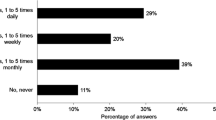

Results of mean Likert scores showed similar results (Fig. 1). GPs and CPs have a very similar perception of who completes the checking of clinical parameters and of medication overuse and underuse. On the other side, there is a considerable difference for tasks such as checking of problems regarding self-medication and adding and removing OTC medicines from the medication list. In general, GPs and CPs show a similar, yet shifted response pattern.

Sub-analysis of MMP task sharing in distinct GP-CP pairs

Of 112 GPs and 163 CPs, 51 unique CP-GP pairs were identified. The GPs have been participating for 4.5 years and CPs for 4.25 years (median; based on time from first enrolment to the point of data collection (end of 2020)). The GP-CP pairs provided medication management for a total of 1623 patients (median: 21 patients, IQR: 11–52). Those pairs showed optimal coordination (sum score = 100%) for four tasks (median, IQR 3–6). However, many pairs had at least one MMP task with a lower sum score (sum score < 100%: n = 37, 72.5%). All pairs had at least for one MMP task a higher sum score (sum score > 100%: n = 51, 100%).

Regarding the different MMP tasks, a sum score < 100% was observed for 14 (27.5%) pairs in checking medication overuse and underuse, 9 (17.6%) for clinical parameters, and 9 (17.6%) for administration times (Fig. 2). A sum score > 100% was obtained for 39 (76.5%) pairs in checking for problems regarding self-medication and for adding and removing OTC medicines from the medication list, 36 (70.6%) for administration times.

Regarding the number of mutual patients for whom a GP-CP pair provided medication management, no trend was observed that pairs with a higher number of mutual patients (as an indicator of their level of involvement in ARMIN MMP) had fewer MMP task with sum scores < 100% (or > 100%).

Discussion

Interprofessional MMP is a complex intervention that requires good coordination and collaboration between GPs and CPs [28, 29]. This study provides information on which MMP tasks GPs and CPs provide and how they perceive their collaboration in interprofessional medication management at the operational level.

GPs perceive that they mainly completed medical tasks such as checking dosing, clinical parameters, and medication overuse and underuse. CPs perceive that they mainly completed pharmaceutical tasks such as initial compilation of the patient’s medication and problems regarding self-medication. However, for many tasks we observed a difference in how GPs and CPs perceived task sharing. For all tasks, except checking clinical parameters, CPs see themselves more responsible than GPs see CPs responsible (and vice versa). GPs’ and CPs’ opinions diverge most concerning problems regarding self-medication, adding and removing OTC medicines from the medication list, and the continuous updating of the medication list. In contrast, GPs and CPs agreed most that checking clinical parameters and medication overuse and underuse are medical tasks and initial compilation of the patient’s medication including brown bag review and storage condition of drugs are pharmaceutical tasks. Furthermore, both GPs and CPs considered checking potential drug-drug interactions rather a pharmaceutical than a medical task.

These findings align with the initially planned and designated tasks in the ARMIN MMP, which defined that GPs should complete medical tasks, such as checking guideline-adherence, and CPs should complete pharmaceutical tasks, such as the initial compilation of the patient's medication including brown bag review [30]. Although some flexibility in MMP task sharing is needed and has to be well-coordinated, the concept of the interprofessional MMP in ARMIN might serve as a blueprint for how tasks between GPs and CPs could be shared in future MMP, at least in Germany [31]. In addition, the involvement of CPs in MMP could respond to the desire of GPs to be supported by trained pharmacists when GPs are facing increased workloads due to growing number of patients with chronic conditions [32].

Furthermore, we examined how GP-CP pairs recognize sharing of MMP tasks. A sum score < 100% shows less mutual recognition than a sum score > 100%. We hypothesize that a sum score < 100% could indicate that a given task is not sufficiently addressed by a GP-CP pair and, therefore, needs special attention in interprofessional medication management programs. A sum score > 100% could indicate high mutual recognition or it might suggest that a particular task is not being performed efficiently, because both HCPs are investing more time and resources than might be necessary. If one might want to take a deeper look in how medication management is performed, deviating or irregular sum scores might give an indication on where it is worth taking a closer look. This might be true when comparing sum scores of different tasks within one GP-CP pair but also when comparing sum scores of distinct tasks. In this study we investigated 15 tasks of which 11 tasks are distinct checks performed during medication reviews. Obviously, there are tasks where a sum score > 100% is likely, because both HCPs perform the same task as part of their professional role. For example, checking drug-drug interaction or non-adherence in duplicate might be reasonable because those tasks require comprehensive information gathering and intense patient counselling (ideally by both HCPs). Other tasks such as checking clinical parameters and the storage conditions of drugs, should be clearly attributed to one HCP only to increase efficiency. Hence, also given a potential recall bias, deviant sum scores might be an indicator that the process of the interprofessional medication management could be improved. Also, a sum score < 100% most likely indicates that the process of the interprofessional medication management could be improved. For example, the check of medication overuse and underuse should be addressed and could be improved because more than a quarter of the GP-CP pairs had a sum score < 100%. This could be addressed by suggesting available effective and validated tools to detect overuse and underuse [33, 34]. The importance of taking action here is underlined by the fact that drug use without indication and untreated/undertreated indication ranks among the top four DRPs in large ambulatory populations [35]. More than 15% of the GP-CP pairs had sum scores < 100% for clinical parameters, administration times, dosing, and explanation of and handing out the medication list. This gap of coordination could potentially lead to a gap in performed DRP checks in MMP and subsequently even impair medication safety. As an example, inappropriately low dosing of direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation does not only result in lower plasma concentrations but also in more severe strokes and worse functional outcomes [36]. However, for most MMP tasks, most GP-CP pairs had sum scores > 100%, possibly indicating that both HCPs overlap in performing MMP tasks. Still, it has to be further investigated if the observed overlap corresponds with different perceptions of both HCPs, intentional double-checking, or redundancy (or if high sum scores are primarily the result of social desirability bias).

Two further findings deserve closer examination. First, collaborating GPs and CPs do not always seem to have the same idea of who performs which tasks and to what extent, a finding that has been reported previously [37]. In some cases, each HCP of a pair indicated that they were doing a task mainly (or even alone) – without knowing or acknowledging that the corresponding collaborating HCP was also involved. Therefore, communication between both HCPs about exactly this content would be important to minimize the workload in this GP-CP pair and to optimize the content of the joint care. Second, there may be discussion about which tasks could be primarily the responsibility of one HCP and which tasks should be performed by both GPs and CPs. Nonetheless, well-coordinated task sharing and acknowledgement of what had already been accomplished by the other HCP could possibly limit redundancy in both workflows and, therefore, reduce workload and ultimately save time and money. However, this trade-off must be made very carefully, as, with fewer double checks, medication errors could go undetected more easily, especially with high risk drugs [38].

Therefore, both HCPs should be in close and continuous coordination with each other. On the one hand, to avoid potential gaps in medication safety, and on the other hand, to save resources.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we conducted a cross-sectional study, preventing any analysis of potential trends over time such as fewer cases of potential gaps in the provision of MMP with increasing time of HCPs’ participation. However, we analyzed potential gaps – that is, GPs and CPs underperforming a MMP task, depending on the number of patients shared by a GP-CP pair as an indicator of their level of involvement in ARMIN MMP. Furthermore, we observed many MMP tasks with sum scores > 100%. This result could be due to the fact that HCPs chose a response indicating more responsibility and effort (social-desirability bias). Also, participants might have remembered only the last few patients (recall bias). However, as patients usually visit GPs and CPs regularly (at least every 3 months) recall bias was probably low. Overall, the participation of CPs and GPs in the MMP was rather low, limiting the generalizability of our findings. However, a high response rate of approximately 70% for both HCPs suggests that the survey results are representative for the study population of MMP participants. Another limitation is, that this was an explorative study that can only propose hypotheses about the potential reasons for and impact of insufficient coordination in MMP on medication safety and effectiveness. Future studies should investigate which tasks need overlapping and in which proportions they should be carried out by which HCP, so that the best possible drug therapy results for the patient.

Conclusions

In general, GPs and CPs participating in the ARMIN program shared most of the tasks in the interprofessional MMP, as envisaged in the original concept, and many of their tasks complemented each other. In some tasks, however, the allocation was less clear, which might have led to tasks either not being carried out sufficiently or being carried out in duplicate. In projects where tasks overlap, ways should be found to promote interprofessional communication in order to save resources and close gaps in care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the contract between the sponsor (SHI fund) and the contractor (researchers) does not allow the publication or sharing of data. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the SHI fund.

Abbreviations

- ARMIN:

-

Arzneimittelinitiative Sachsen-Thüringen

- CP:

-

Community pharmacist

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- HCP:

-

Healthcare professional

- MMP:

-

Medication management program

- MR:

-

Medication review

- OTC:

-

Over-the-counter

- SHI:

-

Statutory health insurance

References

Al-Babtain B, Cheema E, Hadi MA. Impact of community-pharmacist-led medication review programmes on patient outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022;18:2559–68.

Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Sudhakaran S, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in community settings: An overview of systematic reviews. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13:661–85.

Kwint H-F, Bermingham L, Faber A, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. The relationship between the extent of collaboration of general practitioners and pharmacists and the implementation of recommendations arising from medication review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:91–102.

Norton MC, Haftman ME, Buzzard LN. Impact of Physician-Pharmacist Collaboration on Diabetes Outcomes and Health Care Use. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:745–53.

Hunt JS, Siemienczuk J, Pape G, et al. A randomized controlled trial of team-based care: impact of physician-pharmacist collaboration on uncontrolled hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1966–72.

Smith SM, Carris NW, Dietrich E, et al. Physician-pharmacist collaboration versus usual care for treatment-resistant hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:307–17.

Peterson J, Hinds A, Garza A, et al. Impact of Physician-Pharmacist Covisits at a Primary Care Clinic in Patients With Uncontrolled Diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2020;33:321–5.

Carter BL, Coffey CS, Ardery G, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of a physician/pharmacist collaborative model to improve blood pressure control. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:235–43.

Farland MZ, Byrd DC, McFarland MS, et al. Pharmacist-physician collaboration for diabetes care: the diabetes initiative program. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:781–9.

Hwang AY, Gums TH, Gums JG. The benefits of physician-pharmacist collaboration. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:E1-e8.

Hazen ACM, de Bont AA, Boelman L, et al. The degree of integration of non-dispensing pharmacists in primary care practice and the impact on health outcomes: A systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018;14:228–40.

Imfeld-Isenegger TL, Soares IB, Makovec UN, et al. Community pharmacist-led medication review procedures across Europe: Characterization, implementation and remuneration. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16:1057–66.

Mulvale G, Embrett M, Razavi SD. ‘Gearing Up’ to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care: a systematic review and conceptual framework. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:83.

Hossain LN, Fernandez-Llimos F, Luckett T, et al. Qualitative meta-synthesis of barriers and facilitators that influence the implementation of community pharmacy services: perspectives of patients, nurses and general medical practitioners. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e015471.

McNab D, Bowie P, Ross A, MacWalter G, Ryan M, Morrison J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:308–20.

Kallio SE, Kiiski A, Airaksinen MSA, et al. Community Pharmacists’ Contribution to Medication Reviews for Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1613–20.

Chen TF, de Almeida Neto AC. Exploring elements of interprofessional collaboration between pharmacists and physicians in medication review. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:574–6.

de Almeida Neto AC, Chen TF. When pharmacotherapeutic recommendations may lead to the reverse effect on physician decision-making. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:3–8.

Bryant L, Coster G, McCormick R. General practitioner perceptions of clinical medication reviews undertaken by community pharmacists. J Prim Health Care. 2010;2:225–33.

Snyder ME, Zillich AJ, Primack BA, et al. Exploring successful community pharmacist-physician collaborative working relationships using mixed methods. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2010;6:307–23.

Geurts MM, Stewart RE, Brouwers JR, de Graeff PA, de Gier JJ. Implications of a clinical medication review and a pharmaceutical care plan of polypharmacy patients with a cardiovascular disorder. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:808–15.

ABDA – Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände e. V. Grundsatzpapier zur Medikationsanalyse und zum Medikationsmanagement - Überblick über die verschiedenen Konzepte zur Medikationsanalyse und zum Medikationsmanagement als apothekerliche Tätigkeit. Available from: https://www.abda.de/fileadmin/user_upload/assets/Medikationsmanagement/Grundsatzpapier_MA_MM_GBAM.pdf. Accessed: 2022/02/22.

Müller U, Schulz M. Mätzler M [Electronically supported co-operation of physicians and pharmacists to improve medication safety in the ambulatory setting : The “Arzneimittelinitiative Sachsen-Thüringen” (ARMIN)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2018;61:1119–28.

ARMIN Vertragspartner. Modellvorhaben zur Optimierung der Arzneimittelversorgung in Sachsen und Thüringen - Anlage 11 Medikationsmanagement. Available from: https://www.arzneimittelinitiative.de/fileadmin/data/armin/Grundlagen/Anlage_11_Medikationsmanagement.pdf. Accessed: 2021/12/09.

Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Luu Lam Thang T, et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:3179–87.

Weissenborn M, Krass I, Van C, et al. Process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of two Australian instruments to evaluate the physician-pharmacist collaboration in Germany. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16:74–83.

Faulbaum F, Prüfer P, Rexroth M. Was ist eine gute Frage? Die systematische Evaluation der Fragequalität. 1. Auflage ed: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2009.

Ferreri SP, Hughes TD, Snyder ME. Medication Therapy Management: Current Challenges. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2020;9:71–81.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

Eickhoff C, Griese-Mammen N, Müeller U, Said A, Schulz M. Primary healthcare policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Germany. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2021;19(1):2248.

Deutscher Bundestag. Drucksache 19/21732 - Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Stärkung der Vor-Ort-Apotheken 2020.

Loffler C, Koudmani C, Bohmer F, et al. Perceptions of interprofessional collaboration of general practitioners and community pharmacists - a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:224.

O’Mahony D. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate medications/potential prescribing omissions in older people: origin and progress. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13:15–22.

Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M. The FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List 2018: Third Version of a Validated Clinical Tool for Improved Drug Treatment in Older People. Drugs Aging. 2019;36:481–4.

Bankes D, Pizzolato K, Finnel S, et al. Medication-related problems identified by pharmacists in an enhanced medication therapy management model. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27:S292-s299.

Stoll S, Macha K, Marsch A, et al. Ischemic stroke and dose adjustment of oral Factor Xa inhibitors in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Neurol. 2020;267:2007–12.

Bollen A, Harrison R, Aslani P, van Haastregt JCM. Factors influencing interprofessional collaboration between community pharmacists and general practitioners—A systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27:e189–212.

Pfeiffer Y, Zimmermann C, Schwappach DLB. What do double-check routines actually detect? An observational assessment and qualitative analysis of identified inconsistencies. BMJ Open. 2020;10: e039291.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all GPs and CPs for their participation in this study.

ARMIN Study Group members: Anja Auerbach7, Dorit Braun4, Catharina Doehler8, Susanne Donner9; Stefan Fink10, Jona Frasch3, Christine Honscha9, Urs Dieter Kuhn7, Mike Maetzler8, Ulf Maywald4, Andreas D. Meid2, Anke Moeckel7, Carmen Ruff2, Felicitas Stoll2, Kathrin Wagner10 Affiliations: 7 Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians – Thuringia 8Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians – Saxony 9 State Association of Pharmacists – Saxony 10State Association of Pharmacists – Thuringia

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was funded by the SHI fund AOK PLUS, the ABDA – Federal Union of German Associations of Pharmacists, the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians – Saxony, and the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians – Thuringia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Robert Moecker: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft; Marina Weissenborn: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing – review & editing; Anja Klingenberg: methodology, data collection, writing—review & editing; Lucas Wirbka: formal analysis; Andreas Fuchs: project administration, resources, validation; Christiane Eickhoff: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review & editing; Uta Mueller: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review & editing; Martin Schulz: methodology, supervision, writing – review & editing; Petra Kaufmann-Kolle: conceptualization, funding acquisition; project administration, supervision, writing—review & editing; ARMIN Study Group: conceptualization, writing—review & editing; Walter E. Haefeli: resources, writing – review & editing; Hanna M. Seidling: conceptualization, methodology, supervision of investigation and formal analysis, writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All HCPs participated voluntarily and gave their informed consent before being included in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approvals were obtained from the responsible Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University (reference no.: S-142/2019 and S-230/2019).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RM, MW, LW, WEH, and HMS declare they have received funding from the AOK PLUS. AK, PKK, and JF received funding from Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacoepidemiology. Furthermore, the following members of the ARMIN study group have contributed to program development and conduct: CE, UM, MS, AF, DB, UM, CD, MM, AA, UDK, AM, CH, SD, SF, KW.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Moecker, R., Weissenborn, M., Klingenberg, A. et al. Task sharing in an interprofessional medication management program – a survey of general practitioners and community pharmacists. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 1005 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08378-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08378-4