Abstract

Background

We previously developed a Quality Improvement (QI) Return-on-Investment (ROI) conceptual framework for large-scale healthcare QI programmes. We defined ROI as any monetary or non-monetary value or benefit derived from QI. We called the framework the QI-ROI conceptual framework. The current study describes the different categories of benefits covered by this framework and explores the relationships between these benefits.

Methods

We searched Medline, Embase, Global health, PsycInfo, EconLit, NHS EED, Web of Science, Google Scholar, organisational journals, and citations, using ROI or returns-on-investment concepts (e.g., cost–benefit, cost-effectiveness, value) combined with healthcare and QI. Our analysis was informed by Complexity Theory in view of the complexity of large QI programmes. We used Framework analysis to analyse the data using a preliminary ROI conceptual framework that was based on organisational obligations towards its stakeholders. Included articles discussed at least three organisational benefits towards these obligations, with at least one financial or patient benefit. We synthesized the different QI benefits discussed.

Results

We retrieved 10 428 articles. One hundred and two (102) articles were selected for full text screening. Of these 34 were excluded and 68 included. Included articles were QI economic, effectiveness, process, and impact evaluations as well as conceptual literature. Based on these literatures, we reviewed and updated our QI-ROI conceptual framework from our first study. Our QI-ROI conceptual framework consists of four categories: 1) organisational performance, 2) organisational development, 3) external outcomes, and 4) unintended outcomes (positive and negative). We found that QI benefits are interlinked, and that ROI in large-scale QI is not merely an end-outcome; there are earlier benefits that matter to organisations that contribute to overall ROI. Organisations also found positive aspects of negative unintended consequences, such as learning from failed QI.

Discussion and conclusion

Our analysis indicated that the QI-ROI conceptual framework is made-up of multi-faceted and interconnected benefits from large-scale QI programmes. One or more of these may be desirable depending on each organisation’s goals and objectives, as well as stage of development. As such, it is possible for organisations to deduce incremental benefits or returns-on-investments throughout a programme lifecycle that are relevant and legitimate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health services worldwide are faced with challenges to improve the safety and quality of care whilst managing rising healthcare costs [1,2,3,4]. One way to improve healthcare quality is through Quality Improvement (QI). QI is a systematic approach to improving healthcare quality as well as strengthening health systems and reducing costs [5, 6]. QI uses sets of methods such as Lean and Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) [7]. These methods often incorporate analysis, improvement or reconfiguring, and monitoring of systems. QI is guided by Implementation and Improvement Sciences in the targeted design of improvement strategies to maximise programmes’ success [8]. QI can be implemented as small projects or large programmes aimed at benefiting entire organisations or health systems [9, 10]. Healthcare is a complex system as it involves connections, actions and interactions of multiple stakeholders and processes [11]. Therefore, QI in healthcare is a complex intervention. This complexity can be costly.

QI may require significant investment to implement and maintain [12, 13]. QI implementers must therefore demonstrate its value to help leaders justify and account for their investment decisions [14, 15]. QI outcomes are assessed through programme evaluations, comparative research, and economic evaluations such as Return on Investment (ROI). ROI is increasingly being recommended for evaluating or forecasting financial returns (making a business case) for healthcare programmes [16, 17]. Originally from accounting and economics, ROI methods calculate a programme’s costs against its benefits [18]. All perceived programme benefits must be converted to money (monetised) and reported as a single ratio or percentage, e.g., ROI of 1:1 means a 100% profit was made [19]. A favourable ROI is where a positive estimation of a financial return from an investment can be made [19, 20]. However, most healthcare benefits are not amenable to monetisation [20]. Additionally, healthcare QI programmes do not often make a profit or save costs [21]. This raises questions of ROI utility in QI programmes.

ROI was introduced into healthcare as a simple objective measure of a programme’s success [16]. However, in practice, ROI methodology has been found to be complicated and sophisticated [22]. ROI has also been found to misrepresent reality due to its inability to incorporate certain crucial programme outcomes that are valued in healthcare [23]. The concerns over ROI have resulted in various attempts to refashion it. Today, there are ROI methods that encourage detailing of non-monetisable qualitative benefits in some way in addition to monetised benefits [24, 25]. However, these methods still prioritise monetisable benefits [19, 20]. As such, some have referred to ROI as insincere and synthetic [24, 26].

The suitability of ROI as a method for evaluating the value of QI in healthcare and other service industries has been contested for decades [23, 27,28,29,30,31,32]. Within and outside healthcare, others have requested a ‘return to value’ rather a focus on financial outcomes [33] or renamed ROI as ROQ ‘return on quality’ where quality and not profit is favoured [34]. This hints at ROI being a concept. As a concept, ROI encapsulates mental abstractions of how costs and benefits are perceived [35, 36]. Thus, the apparent lack of ROI acceptance in healthcare suggests a need to understand ROI as a concept of a return-on-investment. Understanding the meaning of concepts in research is deemed a crucial step in advancing scientific inquiry [36].

This report is the second part of a larger study on the concept and determinants of ROI from large-scale healthcare QI. The current and previous studies were to develop the ROI concept and a framework for understanding the ROI concept in the healthcare context. The third study will focus on the determinants. In the first part (under submission), we developed the QI-ROI concept by differentiating ROI from similar concepts. In that study, we found that patient outcomes were seen as of primary importance. In addition, several other organisational benefits including financial benefits were also seen as important. We concluded that ROI in healthcare QI represents any valued benefit. We translated this conceptualisation as follows: attaining a return-on-investment whatever that is, is valued and therefore of benefit, and any benefit is of value in and of itself. We then proposed a framework for analysis of return-on-investment from QI programmes. We called this a QI-ROI conceptual framework.

In the current study, we sought to deepen our understanding of the QI-ROI concept. Gelman and Kalish stated that “concepts correspond to categories of things in the real world and are embedded in larger knowledge structures…the building blocks of ideas” [35] (p. 298). Therefore, in the current study, we aimed to search for these building blocks of the QI-ROI concept. The objective was to further develop the QI-ROI framework by exploring the categories of goals and benefits that reflect ROI from large-scale QI programmes. In other words, what QI authors and experts would deem or have deemed a return-on-investment from QI programmes. This knowledge was then used to compile types of benefits that if achieved, represent the QI-ROI. We also explored if and how QI benefits are linked to each other. The linkages were crucial in gaining insights into how the complexity of healthcare as well as QI as a complex intervention may impact ROI evaluation.

Methods

Underpinning theory

Our wider research project on the ROI concept is informed and underpinned by Complexity Theory. We deemed this theory pertinent, given the multiple QI objectives of multiple healthcare stakeholders. Complexity Theory encompasses a group of theories from different disciplines that highlight the interdependent, interconnected, and interrelated nature of a system i.e., human and technological components of an organisation [11, 37, 38]. These components influence each other in unpredictable ways with emergent consequences [11]. Therefore, complexity may lead to uncertainties, benefits, and challenges that may impact ROI. Various tools can be used to study this complexity in QI programmes [8, 39, 40]. However, in this study, Complexity Theory was used only to highlight the complexity during our analysis rather than to study it. We will examine this complexity in detail in our next study on ROI determinants.

Review type

This paper is part of a larger Integrative Systematic Review on the ROI concept and its determinants from healthcare QI programmes. Our review is registered with PROSPERO, CRD42021236948. We have amended the protocol firstly to add additional authors as the complexity of the review called for more author perspectives. Secondly, we added the use of Framework analysis instead of Thematic analysis. A link to our PRISMA reporting checklist [25] is included in the supplementary files. We followed review guidance on Integrated Reviews by Whittemore and Knafl [41] and Conceptual Framework Development by Jabareen [42]. This led to 8 separate review stages. Stage 1; clarifying research question, involved background reading as is discussed in our protocol on PROSPERO. The remainder of the stages are reported here. Stages 2–3 involved searching and selecting literature. In stage 4 we assessed the quality of research studies, stages 5–8 are reported in the synthesis, analysis, and results sections below.

Stage 2

Search strategy

We searched Medline, Embase, Global health, PsycInfo, EconLit, NHS EED, Web of Science, Google, Google scholar, organisational journals, as well hand-searched citations. Search terms were from these three categories: (1) healthcare or health*, (2) ROI related economic evaluation terms (SROI, CBA, CEA, CUA), as well as terms value, benefit, and outcomes, and (3) QI, and its specific methods. Table 1 contains definitions of search terms. No language/date limits were set to enable us to note any changes in QI-ROI conceptualisation over time. The search ended on January 30th, 2021. The search strategy is provided as Supplementary Table 1.

Eligibility

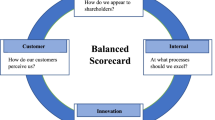

During our initial search, many articles identified themselves as large-scale QI programmes. To focus our selection criteria, we developed a preliminary ROI conceptual framework (Fig. 1). This framework contained various needs and obligations of healthcare organisations [53, 54], which we assumed to signal desired organisational outcomes. The Framework had four criteria: 1) organisational performance (patients and financial outcomes), 2) organisational capacity and capability, 3) external relations (e.g., accreditation), and 4) unintended consequences (positive/negative). Organisational performance is a marker of how well organisations perform on delivering value for its stakeholders [55]. Thus, in a way it includes external relations, e.g., population health. However, they have been isolated here to deduce some unique external outcomes and obligations towards external stakeholders. We then used this framework to decide on eligibility. We included literature on discussions and evaluations of large-scale QI programmes at all healthcare levels (primary, secondary, tertiary) globally.

We included literature that mentioned at least three QI organisational goals or benefits, two of which had to be patient or financial outcomes. By doing this, we sought to isolate articles that discussed a wide range of QI outcomes, with patient and financial outcomes as basic organisational QI performance goals. In addition, articles had to mention use of at least one QI method and involvement of various stakeholders, in at least two organisational units. Altogether, this denoted a three-dimensional criteria: depth, breath, and complexity of programmes per organisation. Table 2 has Included/excluded article types.

Stage 3

Screening and selection of articles

Citations were downloaded onto Endnote, Clarivate [56] to compile a list of citations and remove duplicates. Rayyan software [57] was used to screen abstracts and full titles as per our search criteria. Screening and selection were performed by two independent reviewers, ST and MM. To refine our selection criteria, five articles were initially selected and discussed to clarify any uncertainties. The two reviewers then completed the screening and selection of the remaining articles independently: ST 100%, MM 5%. Overall agreement was over 90%. Disagreements were discussed and settled by ST and MM, as well as with co-author CH.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed using words and phrases in the preliminary conceptual framework as well as outcomes in the review’s search terms. We searched for these from all parts of an article where QI benefits, outcomes, and goals may be discussed. This included the introduction, aims, objectives, results as well as discussion and conclusion. Articles were tabulated according to type of article, country, setting, programme type, and outcomes discussed. Data extraction file has been included as Supplementary Table 2.

Stage 4

Quality assessment

For researchers of integrative reviews and conceptual development, quality assessment is optional as the quality of studies has little or no bearing on concept development [41, 42]. As such, there was no intention to exclude articles based on their quality. However, to understand the scientific context in which QI benefits are discussed, we assessed all empirical studies using specific quality assessment and reporting tools. For reviews, we used Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [58], for mixed methods, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [59], for implementation studies; Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (STaRI) [60]. For economic evaluations, the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) [61], and for QI, the Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) [62]. As these are different tools, there was no single criteria to judge collective study quality. We therefore assessed the number of appropriate items reported or addressed as per respective study’s tool. We assigned good if 80–100% items were addressed, moderate if 50–79% of items were addressed, and poor if less than 50%.

Stages 5–7

Data integration, synthesis, and analysis

We followed Framework Analysis [63], using guidance by Braun & Clarke [64] thematic analysis, and deductive-inductive hybrid analysis by Fereday & Muir-Cochrane [65]. This allowed us to identify data from our ROI preliminary conceptual framework as well as any emerging data related to ROI. During the synthesis we summarised findings from the integrated literature and compiled a table of themes, sub-themes, and related outcomes. In the analysis, we noted the complexity and relationships between these themes and outcomes.

The result was a developed QI-ROI framework that outlines the ROI concepts from our first study (e.g., efficiency, productivity, cost-management, cost-saving). Productivity is the quantity of outputs/returns (e.g., patients seen) per investment/input (e.g., staff). Efficiency is achieving those outputs from same or less inputs with least or no waste (e.g., in time, money, effort) [66]. Cost management are certain strategies used to manage cost [67]. Cost saving can be an outcome of efficiency, productivity, and cost-management. This initial QI-ROI framework was combined with the categories of QI benefits from the current study to form an extended QI-ROI framework.

Stage 8

Results

A total of 10 428 articles were retrieved, 10 327 were excluded for various reason as shown in Fig. 2. One hundred and two (102) articles were eligible, 34 were excluded and 68 included. Included articles were: Conceptual n = 24, Quantitative studies n = 19, Qualitative studies n = 3, Mixed-Methods studies n = 8, Systematic Reviews n = 8, Literature reviews n = 2, Brief Reports n = 4. Together, the articles represent 18 years of QI evaluation (2002–2020). Excluded articles were where programmes engaged a single department and/or discussed two or fewer QI outcomes/goals. Thirteen of these were collaboratives. There was one pre-print. A link to the excluded studies document is available in the supplementary files.

Article characteristics

Included articles covered different healthcare levels and disciplines. Primary care included public health, child and maternal health, and mental health. Secondary and tertiary healthcare included mental health, medical and surgical care, critical care, accident and emergency and acute care services, paediatrics and neonatal care, outpatients, pharmacy, and laboratories. One article covered both health and social care, and another article was about QI in a healthcare related charitable organisation. Articles were from these global regions: Africa, Asia, Europe, Australia, and Canada. The mostly represented regions were the US and the UK. Only 15 of 68 articles were economically focused. ROI was a specific subject of only four articles [68,69,70,71], and five authors discussed development of QI business cases [33, 72,73,74,75]. One article discussed cost–benefit analysis from a qualitative perspective [76], there were two economic systematic reviews, and three economic evaluations. de la Perrelle et al. [77] also found this lack of economic evaluations in their systematic review. However some authors reported their implementation costs [78,79,80]. The summary of included studies can be found as Supplementary Table 3.

Quality of studies

Thirty articles were not subject to quality assessment. These were conceptual articles, unsystematic literature reviews, and brief reports. Thirty-eight articles were subjected to quality assessment: 19 quantitative studies, three qualitative studies, eight mixed-methods studies, and eight systematic reviews. Of the 38 studies, 39% reported or addressed 80%-100% of all items required, 43% reported on 50%-79% of the data required, and 18% reported below 50% of items required by their respective reporting tool. The main areas of poor rigour were: ethics (29%), statistical analysis methods (75%), discussion and management of study limitations (42%). For some mixed methods studies (29%), integration of quantitative and qualitative data was unclear. In some cases, these issues may merely reflect poor reporting. However in the absence of data, poor rigour was assumed. Overall, the quality of the studies was summed-up as moderate. The quality assessment summary is provided as Supplementary Table 4.

Data synthesis and analysis

Authors either directly studied QI outcomes, reported additional QI outcomes and benefits, and or discussed QI goals and missed opportunities. A number of papers reported financial savings or had savings as a goal [77, 81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88]. Gandjour & Lauterbach [89] noted that cost-saving was more likely when improving an over-use or misuse problem. For example, an article reported cost-reduction from malpractice suits [74]. Financial benefits through QI were mostly internal to organisations, and a small number involved societies and healthcare funders [73, 75].

There was a shared view that quality and patient safety should be more central to QI and investment goals than financial outcomes [72, 88, 90,91,92,93,94,95]. This view had not changed over time. Thus, QI goals were primarily improving patient outcomes through systems, structural, process, and behavioural improvements. This enabled improved efficiency and productivity. Efficiency and productivity enabled managers’ abilities to manage, minimise, or reduce costs, and eventually save costs [73, 94, 96,97,98]. Systems efficiency helped improve staff efficiency, effectiveness, productivity, and experience, which benefited patients [84, 99, 100]. Improved systems enabled improved organisational capacity, capability, and resilience [93, 101,102,103,104,105,106].

Most authors highlighted that good quality and patient safety relied upon good staff outcomes and leadership. A few studies focused on some of these specific areas. Examples include Mery et al. [71] who studied QI programmes as an organisational capability and capacity development tool. Hatcher [83] studied QI as a staff safety promotion tool, Lavoie-Tremblay et al. [99] evaluated QI as a tool for team effectiveness. Furukawa et al. [107] and Heitmiller et al. [84] focused QI towards environment sustainability. MacVane [96] saw QI as a governance tool. Williams et al. [100] focused on both staff and patient outcomes. QI was also used to operationalise organisations’ strategies [93, 108]. Staines et al. [108] found that a positive QI reputation allowed recruitment of a suitable CEO.

There was a general recognition that QI does not always achieve its intended goals. Additionally, some QI strategies were more successful than others [80]. Particularly, some literature reviews and empirical studies reported variable, mixed, or inconclusive results [86, 109,110,111,112,113,114,115], even a decline in quality [99]. A few articles discussed negative unintended outcomes [81, 100, 104, 110, 112, 114, 116,117,118,119]. de la Perrelle et al. [77] noted this lack of reporting of negative findings in their review. They suspected this to be due to publication bias. Rationales for not achieving goals were given as implementation difficulties related to contextual and behavioural challenges [78, 114, 120, 121].

Some authors noted that overall benefits accrued over time during phases of a programme’s implementation process [80, 122]. Morganti et al. [123] noted different measures of QI success but suggested that spread of a programme was a measure of lasting success. Sustainability of outcomes was therefore also seen as an important achievement by most authors. This was supported by some of the literature which also indicated that successful QI built legacies mainly through spreading, embedding, and sustaining improvements [78, 93, 101,102,103,104,105,106]. This finding was confirmed by impact studies, extensive QI programme evaluations and discussions of overall QI impacts [69, 85, 87, 93, 103,104,105,106, 108, 115, 116, 119, 121, 124,125,126]. These literatures elaborated on QI goals, failures, and successes, as well as the lessons learnt. Authors suggested that lessons and cultural changes as a result of QI were essential to meeting patient safety needs [93, 109]. Authors highlighted that ultimately, QI benefited a wide range of stakeholders at different levels in different ways.

Themes

Based on the findings, we compiled data into four overarching themes (Table 3). These themes aligned with our ROI preliminary framework; however, adjustments were made to reflect the findings. Organisational capacity and capability was renamed organisational development to acknowledge the broader organisational outcomes. This included all the outcomes that develop and improve organisations’ ability to fulfil their duties. Resilience and QI legacy were additional sub-themes under organisational development. External relations was renamed external outcomes to reflect the broad outcomes beyond relationships with regulators, communities, and other organisations. External outcomes were extended to include collaboration, societal and environmental outcomes, and incentives. Incentives included accreditation, awards, ranking, competitiveness, influence, power, and financial rewards.

Negative unintended outcomes include any negative impact resulting from a QI programme. These were external imposition, top-down distortions, duplication, high resource demands, loss of revenue, and loss of buy-in. Authors reported that at times external or managerial agendas were superimposed over other QI goals [108, 116, 127, 128]. At times this caused duplication of processes (e.g., data collection) and or increased demand on already stretched services. In addition, successful QI can cause loss of funding as services become absolute [108]. Eventually different negative outcomes may cause staff or leaders to disengage from current or future QI.

Positive unintended outcomes were difficult to delineate as often programmes were geared towards patient outcomes but impacted other parts of an organisation in the process. However, as improvement strategies involved changing systems and human behaviours, improvement of these aspects must be intended. We therefore had this sub-theme only include new innovations and opportunities. The final overarching themes were named 1) organisational performance (two sub-themes), 2) organisational development (12 sub-themes), 3) external outcomes (five sub-themes), 4) unintended outcomes (two sub-themes).

Based on the themes, we updated our ROI preliminary conceptual framework to map the four overarching themes that represent QI-ROI (Fig. 3). The beneficial outcomes are presented under the headings “gains, benefits, returns”, whilst negative outcomes are presented as “losses, costs, investments”. These concepts are technically defined differently. They are used together here to denote their co-existence within QI programmes. For example, loss of revenue is a potential investment lost, high resource demands may require investment or incur costs, duplication is inefficient and costly, loss of buy-in is a costly setback. All will raise money spent or lost if not well managed or avoided. They may also affect organisational performance and development, as well as stakeholder engagement in future programmes. Thus, impacts are both monetary and non-monetary.

Updated preliminary ROI Conceptual Framework. Most QI goals and outcomes affect an organisation’s culture. The four overarching themes are connected and influence one another e.g., improved performance enabled attainment of external incentives. An overlap exists amongst these themes, e.g., collaboration was improved both internally (organisational development, and externally as an external QI benefit)

Authors also saw investments as both in monetary and non-monetary forms. These were viewed as both equally essential for patient safety and quality. Some of these investments were part of ongoing organisational strategies. Investments included staff time, recruitment and retention costs, training costs, patient engagement costs [68, 69, 77, 95, 108, 113, 114, 116]. Some investments depended on the goodwill of the staff and patients and were seen as priceless [119]. Staines et al. [108] referred to two types of investments: “hard” infrastructure (e.g., technology) and “soft” infrastructure (e.g., awareness, commitment, and culture).

The literature also noted that QI outcomes are interlinked and interrelated, and as such QI-ROI may not be readily observable. Deducing ROI may require studying “cause-and-effect chains” [92] (p. 2) or an ROI chain; the link between events from a given investment to a given outcome. Sibthorpe et al. [113] saw this as important for understanding QI impacts and attracting QI investment. This can be done by tracking inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes as much as possible throughout a programme. By doing this, the integrity of the ROI chain may be assessed by identifying areas where QI-ROI is created, lost, or influenced. This may then help maximise QI-ROI. However, tracking this chain in complex contexts may be a challenge.

The QI-ROI chain

In complex systems, programme inputs, processes, outputs are not a once-only event, occurring only at initial implementation. Outcomes of earlier inputs, outputs, and processes become inputs in the next phase and so forth until the final impact is achieved (end-ROI). It may therefore be helpful to recognise and celebrate earlier achievements [33, 97]. Further, before a final impact is realised, a programme may act and interact with several variables. Due to this complexity, the linkages may resemble a web rather than a chain. The literature attested to the fact that QI impacts are unpredictable, and difficult to measure [33, 113, 119]. QI inputs may or may not be converted into active QI ingredients that will affect organisational change and improvement [80]. For example, if one of the strategies is to train staff; do they actually learn what is needed? The answer would depend on several internal and external determining factors [78, 79, 114, 120, 121]. Such factors may force adaptations, influence fidelity to strategies, sustainability, and decisions to proceed, de-implement or disinvest.

The ROI chain is illustrated here in Figs. 4 and 5. Figure 4 demonstrates that the overall ROI results from changes in processes, structures, and systems. These may be visible through behavioural (human and systems), and technological improvements, before final impact and ROI can be detected. Two-tier order mechanisms are alluded to here; the first order mechanisms operationalise QI strategies and provide non-monetary ROI, whilst the second order mechanisms convert QI efforts into financial returns. A first order mechanisms may be for example increased staff proficiency leading staff development, whilst a second order may be improved productivity due to increased proficiency. Productivity may then help save costs.

In summary, different investments are made towards a QI programme and a change is propagated through changing and improving processes, behaviours, systems, and structures. Technical (e.g., skills) and social (e.g., culture) changes and improvements may be achieved. These changes and improvements can then lead to improved efficiency and productivity. Efficiency and productivity can then improve cost-management. Better cost-management and control can then lead to cost-reduction, cost-minimisation, cost-avoidance, cost-containment, and cost-saving. All these are outputs, immediate and intermediate outcomes that become mechanisms through which monetary ROI is achieved. Before then, the outputs present as non-monetary returns-on-investments either as enabled abilities (e.g., cost-management, cost-reduction, cost-minimisation, cost-avoidance, cost-containment), outputs or intermediate outcomes (e.g., improved behaviour, productivity, efficiency).

Non-monetary ROI can also be achieved through organisational development e.g., staff development and collaboration. Organisational development is the basis for safe healthcare systems and may lead to cost-saving, and hard cash ROI. Improvements in staff and process outcomes may improve culture, which may also improve patient and financial outcomes. Improvements in patient outcomes may lead to further benefits (e.g., incentives), and become an organisation’s legacy (culture, capacity and capabilities). This can help an organisation become more resilient and sustainable. QI culture and QI legacies are the basis from which future organisational development as well as patient and financial outcomes can be achieved.

Altogether, the QI outcomes contribute to higher goals such as organisational learning, transformation, financial stability, value-based healthcare, and high reliability [101, 102, 105, 116]. Although intended goals and short-term outcomes may be achieved earlier, long-term sustainable impacts depend on successful implementation, embedding a QI safety culture, and developing legacies that support future improvement efforts. Whatever the end-outcome, lessons may be learnt, research, innovation and development may ensue, capacities and capabilities may improve. As Banke-Thomas et al. [68] stated, “ The application of (S)ROI … could be used to inform policy and practice such that the most cost-beneficial interventions are implemented to solve existing (public health) challenges” (p.10).

Figure 5 illustrates the updated QI-ROI conceptual framework in a phased format. This figure represents the current conceptualisation of QI-ROI based on our analysis of the healthcare QI evaluation literature. The processes described here are more complex but have been simplified for clarity. The figure contains the ROI-like concepts from our first study (e.g., efficiency, productivity, effectiveness, cost saving). These concepts are seen here as building blocks of financial ROI. However, some of these also form part of improvements in other organisational performance and developmental goals. Such improvements can be seen as non-monetary ROI which includes improved abilities, development, and overall improved outputs and outcomes. Together, these are the building blocks of the QI-ROI concept as indicated by the literature.

Discussion

The aim of this part of the review was to further develop a framework for understanding the benefits that reflect the concept of ROI from large-scale healthcare QI programmes (the QI-ROI). We achieved this by reviewing different QI literatures on the goals and or benefits from QI programmes. The goals embody aspirations or QI-ROI as imagined, whilst the reported outcomes and benefits represent QI-ROI as experienced. Together, these form a concept of QI-ROI. We considered negative outcomes to be part of this conceptualisation as they may highlight perceptions of the absence of the QI-ROI. We grounded our theoretical assumptions on organisational needs, duties, and obligations as defined by organisations themselves as well as various internal and external stakeholders.

Our assumption was that at a minimum, a QI programme that delivers on any organisational needs and obligations, delivers a return-on-investment for healthcare organisations. The reviewed literature revealed numerous QI goals and outcomes. These included aspects of an organisation’s performance and development, as well as external and unintended QI outcomes. Through the Complexity Theory lens, we noted the different connections of these outcomes. This deepened our understanding of QI-ROI as a collection of interlinked QI benefits that occur incrementally throughout a programme’s lifecycle. These benefits include systems, processual, and structural improvements. Central to these, are sustainable improved patient outcomes.

Although QI effectiveness was not the focus of this review, it is related to QI-ROI. In-fact some view ROI as an overall measure of QI effectiveness [22]. Since the induction of QI into healthcare, a sizeable body of literature have questioned QI’s value and effectiveness [136,137,138,139,140,141,142]. Several factors have been found to determine QI’s success. These include aspects of organisations’ structures, systems, behaviours, cultures, and leadership [143, 144]. The collection of benefits referred to in this review as QI-ROI largely contribute towards these QI effectiveness determinants [145,146,147]. Thus, improvement in these aspects must be of value for organisations. Further, achieving QI’s pre-defined goals (effectiveness) is not the end, but part of the journey towards QI-ROI. This is important to note as depending on the QI resources required, costs may increase, rendering QI value inversely related to its cost [21, 148, 149].

The insights into the building blocks of good quality healthcare are not new and inter-disciplinary health services research attest to this [150,151,152,153]. Wider health and social science as well as organisational literature have repeatedly pointed to the importance of improving staff capacities and capabilities, as well as experience [154]. A systematic review by Hall et al. [155], found that poor staff wellbeing and burnout are frequently associated with poor patient outcomes. Latino [156] argued that the intellectual capital of human beings is one of the greatest benefits not captured through financial outcomes. Implementation and Improvement Sciences have highlighted the importance of understanding contexts, interventions, and human behaviour and their influence on QI programme success and sustainability [39, 40].

Effective leadership was a consistent patient safety pre-requisite in the Francis Mid-Staffordshire review [157]. The Francis review also highlighted negative cultures and failure to learn as contributing factors to poor quality care. Negative QI outcomes and failed attempts must be avoided, but they are part of learning safety cultures [158]. Patient engagement has also been found to be crucial in leaning and safety cultures [159]. A safety culture: one that prioritises safe care, is thus deemed foundational to efforts to improve quality and safety [158, 160,161,162,163,164].

There are of-course other ways to improve healthcare, and organisations do invest in various programmes that specifically target some of the themes within our QI-ROI conceptual framework, for example leadership programmes [165]. Determining whether QI or other types of investments and programmes led to any specific improvement is known to be challenging [166, 167]. As a result, claims of causality are not possible. Through Complexity Theory, QI-ROI can be viewed in terms of contribution or correlation to organisational outcomes rather than direct attribution [11, 37, 166]. Understanding of QI contribution to organisational outcomes may be achieved through methods such as contribution analysis and the action effect method [166, 167]. These methods can help detect the type and level of QI contribution.

QI’s key contributions to healthcare improvement are evident in the reviewed literature, and external bodies such as the UK Care Quality Commission (CQC) attest to this. In 2018, 80% of Trusts rated “Outstanding” by the CQC had organisational improvement programmes [101]. As a result, QI was identified in the UK National Health Service (NHS) Long-term Plan as an approach for improving every aspect of how the NHS operates [168]. Further, organisations that have mature improvement cultures claim to have benefited in several of the QI-ROI conceptual framework’s dimensions [169,170,171]. Mature organisations indicate that, in addition to organisational development and performance, environmental and social impacts [172], reputation, [173], and resilience [174], are crucial organisational outcomes. QI programmes are now also used to engage with modern healthcare agendas like value-based healthcare and environmental sustainability [175, 176]. In achieving such goals, QI programmes can be cost-effective without saving actual costs [177].

However, QI-ROI is not a one-time event. ROI may be created or lost at different stages of a programme [25]. In a complex healthcare programme, QI-ROI is iterative and dynamic with many determinants, some of them outside the control of QI implementers alone [13, 39, 167]. Additionally, QI may affect various levels of stakeholders from frontline, to societies, to policymakers differently. [13, 39, 167]. These levels interact with and influence each other [11, 39]. As such, it is important to note the co-dependencies of QI outcomes when planning and evaluating QI. As Donabedian [178] stated; structures, processes and outcomes are mutually dependent. This means that it is important to take small wins with big wins through observing the QI-ROI chain [179]. Therefore, not only is the traditional ROI approach unreliable as a forecasting tool, as an evaluation tool, it is a distal and an incomplete marker of QI value.

Finally, large-scale programmes took many forms, some internal and some involving external collaborators. Collaborations have been recommended as a way to improve patient safety and experience, and save costs [180, 181]. However, unless formally integrated, organisations run internal budgets, their performance assessed individually, and with own governance structures [14, 182,183,184]. Notably, collaboratives appear to be geared towards health system-wide benefits and indirectly address organisational-level impacts [138]. Therefore, collaboratives may bring unique challenges as well as benefits. This may mean that different organisations at different developmental levels deduce different outcomes from the same QI programmes [102, 146]. Research developments here will be valuable to improve understanding of QI-ROI, for example how and why collaboratives work (or not) [51, 185]. Nonetheless, this review reveals largely shared QI goals and outcomes regardless of the type of large-scale programme.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our review is that our theoretical assumptions were grounded on organisational needs, duties, and obligations as defined by organisations and external stakeholders. This step preceded the first study where we analysed different returns-on-investments concepts in healthcare QI. The current study sought to strengthen the first study’s QI-ROI conceptual framework by connecting the QI-ROI concept with categories of QI benefits as seen by healthcare QI stakeholders. Additionally, our review lens through complexity theory gave us a glimpse of the processes though which these QI-ROI building blocks independently or in concert may influence ROI. As such, our framework provides clues to its practical application.

A limitation of this review is that it was broad, encompassing various disciplines in various countries, reporting on different types of programmes. The review was meant to be an exploration of the QI field’s view of QI returns-on-investment. Researchers may wish to explore these in specific contexts, for example by studying particular “building blocks” of QI-ROI in a specific context or programme. Additionally, some of the literature is quite dated, however newer literature do suggest continuance of some trends and issues in QI-ROI and QI business case matters. Lastly, subjectivity in the synthesis and analysis cannot be ruled out as it is inherent in qualitative analyses [63].

Implications for research and practice

Economic evaluation of large-scale programmes are a new phenomenon, and research is needed to help identify the most suitable evaluation methods. This need is compounded by the fact that large-scale QI programmes come in many forms. It is important to assess QI’s contribution to organisational performance and development through suitable and innovative research methods such as realist reviews rather than seek a definitive causal link which may be imperceptible in complex large QI programmes. A study of collaboratives alone or in comparison to internal organisation-wide QI programmes may help explore the best ways to approach large-scale QI programmes to maximise ROI. In addition, a thorough study of the relationships of the QI-ROI determinants as well as QI benefits may help to understand why and how QI benefits influence one another. Lastly, guidance on how to weigh different QI benefits, and how to develop a standardisable yet flexible QI-ROI tools will be crucial for future research and practical application.

Conclusion

ROI in healthcare is a highly debated topic. This review is but one contribution to this ongoing debate. Our review suggests that in healthcare, ROI must reflect value-based healthcare principles, with value defined as patient and organisational benefits. We hope that by defining the ROI concept in this manner, links between wider large-scale QI benefits and organisational strategic intents will be highlighted. In doing this, leaders may be able to frame QI value, benefits and thus ROI in a useful way. This broader view is crucial if healthcare organisations and health systems are to continue investing in essential healthcare quality improvements. ROI is not a one-time event and may be created or lost at different stages of a programme. Further, many factors determine whether it can be deduced, many of them outside the control of QI implementers. Such factors must be taken into consideration in valuing healthcare QI.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Some data has been included in this published article as its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- QI:

-

Quality Improvement

- ROI:

-

Return on Investment

- SROI:

-

Social Return on Investment

- QI-ROI:

-

Return on Investment from healthcare nhquality improvement

- CEA:

-

Cost Effectiveness Analysis

- CUA:

-

Cost Utility Analysis

- CBA:

-

Cost Benefit Analysis

References

Alderwick H, Charles A, Jones B, Warburton W. Making the case for quality improvement: lessons for NHS boards and leaders. London: King's Fund. 2017.

Hadad S, Hadad Y, Simon-Tuval T. Determinants of healthcare system’s efficiency in OECD countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(2):253–65.

Knapp M, Wong G. Economics and mental health: the current scenario. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):3–14.

Pollack J, Helm J, Adler D. What is the Iron Triangle, and how has it changed? 2018.

Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):2–3.

Øvretveit J, Gustafson D. Evaluation of quality improvement programmes. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(3):270–5.

Boaden R. Quality improvement: theory and practice. Br J Healthc Manag. 2009;15(1):12–6.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):53.

Ovretveit J, Gustafson D. Using research to inform quality programmes. BMJ. 2003;326(7392):759–61.

Benn J, Burnett S, Parand A, Pinto A, Iskander S, et al. Studying large-scale programmes to improve patient safety in whole care systems: challenges for research. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(12):1767–76.

Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, Ellis LA, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 2018;16:1–4.

Roberts SLE, Healey A, Sevdalis N. Use of health economic evaluation in the implementation and improvement science fields-a systematic literature review. Implementation Sci. 2019;14(1):72.

Saldana L, Chamberlain P, Bradford WD, Campbell M, Landsverk J. The Cost of Implementing New Strategies (COINS): a method for mapping implementation resources using the stages of implementation completion. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;39:177–82.

Brinkerhoff DW. Accountability and health systems: toward conceptual clarity and policy relevance. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(6):371–9.

Chua KC, Henderson C, Grey B, Holland M, Sevdalis N. Evaluating quality improvement at scale: routine reporting for executive board governance in a UK National Health Service organisation. medRxiv. 2021: p. 2020.02.13.20022475.

Pokhrel S. Return on investment (ROI) modelling in public health: strengths and limitations. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25(6):908–9.

World Health Organisation (WHO). Making the investment case for mental health: a WHO/UNDP methodological guidance note. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Botchkarev A. Estimating the Accuracy of the Return on Investment (ROI) Performance Evaluations. 2015. arXiv:1404.1990.

Botchkarev A, Andru P. A Return on investment as a metric for evaluating information systems: taxonomy and application. Interdiscip J Inf Knowl Manag. 2011;6:245–69.

Solid CA. Return on investment for healthcare quality improvement. 2020: Springer.

Rauh SS, Wadsworth EB, Weeks WB, Weinstein JN. The savings illusion - Why clinical quality improvement fails to deliver bottom-line results. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):e48.

De Meuse KP, Dai G, Lee RJ. Evaluating the effectiveness of executive coaching: beyond ROI? Coaching Int J Theory Res Pract. 2009;2(2):117–34.

Masters R, Anwar E, Collins B, Cookson R, Capewell S. Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(8):827.

Bukhari H, Andreatta P, Goldiez B, Rabelo L. A framework for determining the return on investment of simulation-based training in health care. Inquiry. 2017;54:0046958016687176.

Phillips PP, Phillips JJ, Edwards LA. Measuring the success of coaching: a step-by-step guide for measuring impact and calculating ROI: American Society for Training and Development. 2012.

Andru P, Botchkarev A. Return on investment: a placebo for the Chief Financial Officer… and other paradoxes. J MultiDiscip Eval. 2011;7(16):201–6.

Boyd J, Epanchin-Niell R, Siikamäki J. Conservation planning: a review of return on investment analysis. Rev Environ Econ Policy. 2015;9(1):23-42.42.

Brousselle A, Benmarhnia T, Benhadj L. What are the benefits and risks of using return on investment to defend public health programs? Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:135–8.

Dearden J. Case against ROI control. Harvard Business Review. 1969.

Ozminkowski RJ, Serxner S, Marlo K, Kichlu R, Ratelis E, Van de Meulebroecke J. Beyond ROI: using value of investment to measure employee health and wellness. Popul Health Manag. 2016;19(4):227–9.

Price CP, McGinley P, John AS. What is the return on investment for laboratory medicine? The antidote to silo budgeting in diagnostics. Br J Healthc Manag. 2020;26(6):1–8.

Lurie N, Somers SA, Fremont A, Angeles J, Murphy EK, Hamblin A. Challenges to using a business case for addressing health disparities. Health Aff. 2008;27(2):334–8.

Fischer HR, Duncan SD. The business case for quality improvement. J Perinatol. 2020;40(6):972–9.

Rust RT, Zahorik AJ, Keiningham TL. Return on quality (ROQ): Making service quality financially accountable. J Mark. 1995;59(2):58–70.

Gelman SA, Kalish CW. Conceptual development. Handbook of child psychology. 2007. p. 2.

Hupcey J, Penrod J. Concept analysis: examining the state of the science. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2005;19:197–208.

Fenwick T. Response to Jeffrey McClellan. Complexity theory, leadership, and the traps of utopia. Complicity: Int J Complex Educ. 2010;7(2):90-96.

Manson SM. Simplifying complexity: a review of complexity theory. Geoforum. 2001;32(3):405–14.

Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, Lysdahl KB, Booth A, Hofmann B, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):21.

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Lowery JC. The consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Handbook on implementation science: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2020.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53.

Jabareen Y. Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8(4):49–62.

Berdot S, Korb-Savoldelli V, Jaccoulet E, Zaugg V, Prognon P, Lê LMM, et al. A centralized automated-dispensing system in a French teaching hospital: return on investment and quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(3):219–24.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW, Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Mason J, Freemantle N, Nazareth I, Eccles M, Haines A, Drummond M. When is it cost-effective to change the behavior of health professionals? JAMA. 2001;286(23):2988–92.

Viner J. The utility concept in value theory and its critics. J Polit Econ. 1925;33(6):638–59.

Chartier LB, Cheng AH, Stang AS, Vaillancourt S. Quality improvement primer part 1: preparing for a quality improvement project in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. 2018;20(1):104–11.

Jones B, Vaux E, Olsson-Brown A. How to get started in quality improvement. BMJ. 2019;364:k5408.

Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIp). A guide to Quality Improvement methods. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership. 2015.

Øvretveit J, Klazinga N. Learning from large-scale quality improvement through comparisons. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(5):463–9.

Schouten LM, Grol RP, Hulscher ME. Factors influencing success in quality-improvement collaboratives: development and psychometric testing of an instrument. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9.

Guidance: The health and care system explained. UK Department of Health and Social Care 2013.

Gartner JB, Lemaire C. Dimensions of performance and related key performance indicators addressed in healthcare organisations: A literature review. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022: 1–12.

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, Adeyi O, Barker P, Daelmans B, Doubova SV, English M. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(11):e1196–252.

Elg M, Broryd KP, Kollberg B. Performance measurement to drive improvements in healthcare practice. Int J Oper Prod Manag. 2013;79(3):13-24.

The EndNote Team, Clarivate. EndnoteTM. [EndNote X9]. 2013.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):1–10.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) 2019. Available from: https://caspuk.net/referencing/#:~:text=Referencing%20%E2%80%93%20We%20would%20recommend%20using,at%3A%20Accessed%3A%20Date%20Accessed. [Cited 2021 24/11].

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of copyright. 2018;1148552:10.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ. 2013;346:f1049.

Ogrinc G, Mooney SE, Estrada C, Foster T, Goldmann D, Hall LW, et al. The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17 Suppl 1(Suppl_1):i13-32.

Parkinson S, Eatough V, Holmes J, Stapley E, Midgley N. Framework analysis: a worked example of a study exploring young people’s experiences of depression. Qual Res Psychol. 2016;13(2):109–29.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92.

Sheiner L, Malinovskaya A. Measuring productivity in healthcare: an analysis of the literature. Hutchins center on fiscal and monetary policy at Brookings. 2016.

Hoffman JM, Koesterer LJ, Swendrzynski RG. ASHP guidelines on medication cost management strategies for hospitals and health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(14):1368–84.

Banke-Thomas AO, Madaj B, Charles A, van den Broek N. Social Return on Investment (SROI) methodology to account for value for money of public health interventions: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):582.

Crawley-Stout LA, Ward KA, See CH, Randolph G. Lessons learned from measuring return on investment in public health quality improvement initiatives. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(2):E28–37.

Moody M, Littlepage L, Paydar N. Measuring social return on investment. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh. 2015;26(1):19–37.

Mery G, Dobrow MJ, Baker GR, Im J, Brown A. Evaluating investment in quality improvement capacity building: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012431.1.

Bailit M, Dyer MB. Beyond bankable dollars: establishing a business case for improving health care. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2004;754:1–12.

Leatherman S, Berwick D, Iles D, Lewin LS, Davidoff F, Nolan T, et al. The business case for quality: case studies and an analysis. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2003;22(2):17.

Perencevich EN, Stone PW, Wright SB, Carmeli Y, Fisman DN, Cosgrove SE, et al. Raising standards while watching the bottom line: making a business case for infection control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(10):1121–33.

Swensen SJ, Dilling JA, Mc Carty PM, Bolton JW, Harper CM Jr. The business case for health-care quality improvement. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(1):44–52.

Rogers PJ, Stevens K, Boymal J. Qualitative cost–benefit evaluation of complex, emergent programs. Eval Program Plann. 2009;32(1):83–90.

de la Perrelle L, Radisic G, Cations M, Kaambwa B, Barbery G, Laver K. Costs and economic evaluations of Quality Improvement Collaboratives in healthcare: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):155.

Fortney J, Enderle M, McDougall S, Clothier J, Otero J, Altman L, et al. Implementation outcomes of evidence-based quality improvement for depression in VA community based outpatient clinics. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):30.

Thursky K, Lingaratnam S, Jayarajan J, Haeusler GM, Teh B, Tew M, et al. Implementation of a whole of hospital sepsis clinical pathway in a cancer hospital: impact on sepsis management, outcomes and costs. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(3):e000355-e.

McGrath BA, Lynch J, Bonvento B, Wallace S, Poole V, Farrell A, et al. Evaluating the quality improvement impact of the Global Tracheostomy Collaborative in four diverse NHS hospitals. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2017;6(1):bmjqir.u220636.w7996.

Bielaszka-DuVernay C. Innovation profile: redesigning acute care processes in Wisconsin. Health Aff. 2011;30(3):422–5.

Comtois J, Paris Y, Poder TG, Chausse S. The organizational benefits of the Kaizen approach at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS). L'approche Kaizen au Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS) : un avantage organisationnel significatif. 2013;25(2):169–77.

Hatcher IB. Reducing sharps injuries among health care workers: a sharps container quality improvement project. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28(7):410–4.

Heitmiller ES, Hill RB, Marshall CE, Parsons BJ, Berkow LC, Barrasso CA, et al. Blood wastage reduction using Lean Sigma methodology. Transfusion. 2010;50(9):1887–96.

Niemeijer GC, Trip A, de Jong LJ, Wendt KW, Does RJ. Impact of 5 years of lean six sigma in a University Medical Center. Qual Manag Health Care. 2012;21(4):262–8.

Strauss R, Cressman A, Cheung M, Weinerman A, Waldman S, Etchells E, et al. Major reductions in unnecessary aspartate aminotransferase and blood urea nitrogen tests with a quality improvement initiative. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(10):809–16.

van den Heuvel J, Does RJMM, Bogers AJJC, Berg M. Implementing six sigma in the Netherlands. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(7):393–9.

Yamamoto J, Abraham D, Malatestinic B. Improving insulin distribution and administration safety using lean six sigma methodologies. Hosp Pharm. 2010;45(3):212–24.

Gandjour A, Lauterbach KW. Cost-effectiveness of quality improvement programs in health care. Med Klin. 2002;97(8):499–502.

Bridges JFP. Lean systems approaches to health technology assessment: a patient-focused alternative to cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:101–9.

Chow-Chua C, Goh M. Framework for evaluating performance and quality improvement in hospitals. Manag Serv Qual: Int J. 2002;12(1):54–66.

Ciarniene R, Vienazindiene M, Vojtovic S. Process improvement for value creation: a case of health care organization. Inzinerine Ekonomika-Engineering Economics. 2017;28(1):79–88.

O'Sullivan Owen P, Chang Nynn H, Baker P, Shah A. Quality improvement at East London NHS Foundation Trust: the pathway to embedding lasting change. Governance IJoH, editor: International Journal of Health Governance; 2020.

Shah A, Course S. Building the business case for quality improvement: a framework for evaluating return on investment. Future Healthc J. 2018;5(2):132–7.

Wood J, Brown B, Bartley A, Margarida Batista Custodio Cavaco A, Roberts AP, Santon K, et al. Reducing pressure ulcers across multiple care settings using a collaborative approach. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(3):e000409.

MacVane PF. Chasing the golden fleece: Increasing healthcare quality, efficiency and patient satisfaction while reducing costs. Int J Health Gov. 2019;24(3):182–6.

McLees AW, Nawaz S, Thomas C, Young A. Defining and assessing quality improvement outcomes: a framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:S167–73.

Neri RA, Mason CE, Demko LA. Application of Six Sigma/CAP methodology: controlling blood-product utilization and costs. J Healthcare Manag/ American College of Healthcare Executives. 2008;53(3):183–6.

Lavoie-Tremblay M, O’Connor P, Biron A, Lavigne GL, Frechette J, Briand A, et al. The effects of the transforming care at the bedside program on perceived team effectiveness and patient outcomes. Health Care Manag. 2017;36(1):10–20.

Williams B, Hibberd C, Baldie D, Duncan EAS, Elders A, Maxwell M, et al. Evaluation of the impact of an augmented model of The Productive Ward: Releasing Time to Care on staff and patient outcomes: a naturalistic stepped-wedge trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;30:27–37.

Care Qualty Commission (CQC). Quality improvement in hospital trusts: sharing learning from trusts on a journey of QI, C.Q. Commission, Editor. 2018.

Bevan H, Plsek P, Winstanley L. Part 1: Leading large scale change: a practical guide What the NHS Academy for Large Scale Change learnt and how you can apply these principles within your own health and healthcare setting. In: Improvement NIfIa, editor. NHS Academy for Large Scale Change. 2011.

The Healthcare Foundation. Safer Patients Initiative: Lessons from the first major improvement programme addressing patient safety in the UK, T.H. Foundation, Editor. 2011.

Hunter DJ, Erskine J, Hicks C, McGovern T, Small A, Lugsden E, et al. Health Services and Delivery Research, in A mixed-methods evaluation of transformational change in NHS North East. 2014. NIHR Journals Library.

NHS Insitute. The Productive Ward: Releasing time to careTM Learning and Impact Review Final report, NHS Institute, Editor. 2011.

Jones B, Horton T, Warburton W. The improvement Journey. The Health Foundation. 2019.

Furukawa PdO, Cunha ICKO, Pedreira MdLG. Avaliação de ações ecologicamente sustentáveis no processo de medicação. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem. 2016;69(1):23–9.

Staines A, Thor J, Robert G. Sustaining improvement? The 20-year Jonkoping quality improvement program revisited. Qual Manag Health Care. 2015;24(1):21–37.

Crema M, Verbano C. Lean Management to support Choosing Wisely in healthcare: the first evidence from a systematic literature review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29(7):889-95.5.

DelliFraine JL, Langabeer JR 2nd, Nembhard IM. Assessing the evidence of Six Sigma and Lean in the health care industry. Qual Manag Health Care. 2010;19(3):211–25.

Moraros J, Lemstra M, Nwankwo C. Lean interventions in healthcare: do they actually work? A systematic literature review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(2):150–65.

Power M, Brewster L, Parry G, Brotherton A, Minion J, Ozieranski P, et al. Multimethod study of a large-scale programme to improve patient safety using a harm-free care approach. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011886.

Sibthorpe B, Gardner K, Chan M, Dowden M, Sargent G, McAullay D. Impacts of continuous quality improvement in Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander primary health care in Australia: a scoping systematic review. J Health Organ Manag. 2018;32(4):545–71.

Stephens TJ, Peden CJ, Pearse RM, Shaw SE, Abbott TEF, Jones EL, et al. Improving care at scale: process evaluation of a multi-component quality improvement intervention to reduce mortality after emergency abdominal surgery (EPOCH trial). Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):142.

Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, Naidoo D, Bekhit M, Goldmann D. Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(3):226–40.

Collins B, Fenney D. Improving patient safety through collaboration a rapid review of the academic health science networks’ patient safety collaboratives. In: Fund Ks, editor. 2019.

Goodridge D, Rana M, Harrison EL, Rotter T, Dobson R, Groot G, et al. Assessing the implementation processes of a large-scale, multi-year quality improvement initiative: survey of health care providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:237.

White M, Wells JS, Butterworth T. The transition of a large-scale quality improvement initiative: a bibliometric analysis of the Productive Ward: Releasing Time to Care Programme. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(17–18):2414–23.

Worrall A, Ramsay A, Gordon K, Maltby S, Beecham J, King S, et al. Evaluation of the Mental Health Improvement Partnerships programme. National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO). 2008.

de Miranda Costa MM, Santana HT, Saturno Hernandez PJ, Carvalho AA, da Silva Gama ZA. Results of a national system-wide quality improvement initiative for the implementation of evidence-based infection prevention practices in Brazilian hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(1):24–34.

Morrow E, Robert G, Maben J, Griffiths P. Implementing large-scale quality improvement: lessons from The Productive Ward: Releasing Time to Care. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2012;25(4):237–53.

Brink AJ, Messina AP, Feldman C, Richards GA, van den Bergh D, Netcare AS. From guidelines to practice: a pharmacist-driven prospective audit and feedback improvement model for peri-operative antibiotic prophylaxis in 34 South African hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(4):1227–34.

Morganti KG, Lovejoy S, Haviland AM, Haas AC, Farley DO. Measuring success for health care quality improvement interventions. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1086–92.

Benning A, Ghaleb M, Suokas A, Dixon-Woods M, Dawson J, Barber N, et al. Large scale organisational intervention to improve patient safety in four UK hospitals: mixed method evaluation. BMJ. 2011;342(7793):369.

Honda AC, Bernardo VZ, Gerolamo MC, Davis MM. How lean six sigma principles improve hospital performance. Qual Manag J. 2018;25(2):70–82.

Pearson M, Hemsley A, Blackwell R, Pegg L, Custerson L. Improving Hospital at Home for frail older people: insights from a quality improvement project to achieve change across regional health and social care sectors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:387.

Masso M, Robert G, McCarthy G, Eagar K. The Clinical Services Redesign Program in New South Wales: perceptions of senior health managers. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34(3):352–9.

Robert G, Sarre S, Maben J, Griffiths P, Chable R. Exploring the sustainability of quality improvement interventions in healthcare organisations: a multiple methods study of the 10-year impact of the ‘Productive Ward: Releasing Time to Care’ programme in English acute hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(1):31.

Beers LS, Godoy L, John T, Long M, Biel MG, Anthony B, et al. Mental Health Screening Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative in Pediatric Primary Care. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20162966.

Bosse G, Abels W, Mtatifikolo F, Ngoli B, Neuner B, Wernecke K-D, et al. Perioperative care and the importance of continuous quality improvement-A controlled intervention study in Three Tanzanian Hospitals. Plos One. 2015;10(9):e0136156.

Botros S, Dunn J. Implementation and spread of a simple and effective way to improve the accuracy of medicines reconciliation on discharge: a hospital-based quality improvement project and success story. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(3):e000363-e.

Kanamori S, Sow S, Castro MC, Matsuno R, Tsuru A, Jimba M. Implementation of 5S management method for lean healthcare at a health center in Senegal: a qualitative study of staff perception. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:27256.

Roney JK, Whitley BE, Long JD. Implementation of a MEWS-Sepsis screening tool: transformational outcomes of a nurse-led evidence-based practice project. Nurs Forum. 2016;55(2):144–8.

Schouten LMT, Niessen LW, van de Pas JWAM, Grol RPTM, Hulscher MEJL. Cost-effectiveness of a quality improvement collaborative focusing on patients with diabetes. Med Care. 2010;48(10):884–91.

Sermersheim ER, Moon MC, Streelman M, McCullum-Smith D, Fromm J, Yohannan S, et al. Improving patient throughput with an electronic nursing handoff process in an academic medical center a rapid improvement event approach. J Nurs Adm. 2020;50(3):174–81.

Appleby J. The quest for quality in the NHS: still searching? BMJ. 2005;331(7508):63–4.

Baines R, Langelaan M, de Bruijne M, Spreeuwenberg P, Wagner C. How effective are patient safety initiatives? A retrospective patient record review study of changes to patient safety over time. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(9):561–71.

Clay-Williams R, Nosrati H, Cunningham FC, Hillman K, Braithwaite J. Do large-scale hospital- and system-wide interventions improve patient outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):369.

Dixon-Woods M, Martin GP. Does quality improvement improve quality? Future Hosp J. 2016;3(3):191–4.

Knudsen SV, Laursen HVB, Johnsen SP, Bartels PD, Ehlers LH, Mainz J. Can quality improvement improve the quality of care? A systematic review of reported effects and methodological rigor in plan-do-study-act projects. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):683.

Nembhard IM, Alexander JA, Hoff TJ, Ramanujam R. Why does the quality of health care continue to lag? Insights from Management Research. Acad Manag Perspect. 2009;23(1):24–42.

Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593–624.

Dixon-Woods M. The problem of context in quality improvement. Perspectives on context London: Health Foundation; 2014. p. 87–101.

McDonald KM, Schultz EM, Chang C. Evaluating the state of quality-improvement science through evidence synthesis: insights from the closing the quality gap series. Perm J. 2013;17(4):52–61.

Farokhzadian J, Nayeri ND, Borhani F. The long way ahead to achieve an effective patient safety culture: challenges perceived by nurses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:654.

Goodwin VA, Hill JJ, Fullam JA, Finning K, Pentecost C, Richards DA. Intervention development and treatment success in UK health technology assessment funded trials of physical rehabilitation: a mixed methods analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e026289.

Irwin R, Stokes T, Marshall T. Practice-level quality improvement interventions in primary care: a review of systematic reviews. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16(6):556–77.

Canovas JJG, Hernandez PJS, Botella JJA. Effectiveness of internal quality assurance programmes in improving clinical practice and reducing costs. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(5):813–9.

Lighter DE. How (and why) do quality improvement professionals measure performance? Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2015;2(1):7–11.

Braithwaite J. Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ. 2018;361:k2014.

Haw JS, Narayan KMV, Ali MK. Quality improvement in diabetes–successful in achieving better care with hopes for prevention. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1353:138–51.

Palmer RH, Louis TA, Peterson HF, Rothrock JK, Strain R, Wright EA. What makes quality assurance effective? Results from a randomized, controlled trial in 16 primary care group practices. Med Care. 1996;34(9):SS29–39.

Rich N, Piercy N. Losing patients: a systems view on healthcare improvement. Prod Plan Control. 2013;24(10–11):962–75.

Brand SL, Thompson Coon J, Fleming LE, Carroll L, Bethel A, Wyatt K. Whole-system approaches to improving the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0188418.

Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159015.

Latino RJ. How is the effectiveness of root cause analysis measured in healthcare? J Healthc Risk Manag. 2015;35(2):21–30.

Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry: executive summary: The Stationery Office. 2013.

Jabbal J, Lewis M. Approaches to better value in the NHS Improving quality and cost. King’s Fund. 2018.

Hara JK, Lawton RJ. At a crossroads? Key challenges and future opportunities for patient involvement in patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(8):565.

Illingworth J. Continuous improvement of patient safety. The case for change in the NHS. The Health Foundation. 2015.

Joly BM, Booth M, Mittal P, Shaler G. Measuring quality improvement in Public Health: the development and psychometric testing of a QI Maturity Tool. Eval Health Prof. 2012;35(2):119–47.

Parast L, Doyle B, Damberg CL, Shetty K, Ganz DA, Wenger NS, et al. Challenges in assessing the process-outcome link in practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):359–64.

Peden CJ, Campbell M, Aggarwal G. Quality, safety, and outcomes in anaesthesia: what’s to be done? An international perspective. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:I5–14.

Zwijnenberg NC, Hendriks M, Delnoij DMJ, de Veer AJE, Spreeuwenberg P, Wagner C. Understanding and using quality information for quality improvement: the effect of information presentation. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(6):689–97.

Parmelli E, Flodgren G, Beyer F, Baillie N, Schaafsma ME, Eccles MP. The effectiveness of strategies to change organisational culture to improve healthcare performance: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):33.

Mayne J. Contribution analysis: Addressing cause and effect. Evaluating the complex. 2011. p. 53–96.

Reed JE, McNicholas C, Woodcock T, Issen L, Bell D. Designing quality improvement initiatives: the action effect method, a structured approach to identifying and articulating programme theory. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(12):1040.

National Health Service (NHS). NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan 2019/20 – 2023/24, NHS, Editor. 2019.

Middleton LP, Phipps R, Routbort M, Prieto V, Medeiros LJ, Riben M, et al. Fifteen-year journey to high reliability in pathology and laboratory medicine. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33(5):530–9.

Taylor N, Clay-Williams R, Hogden E, Braithwaite J, Groene O. High performing hospitals: a qualitative systematic review of associated factors and practical strategies for improvement. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):244.

Woodhouse KD, Volz E, Maity A, Gabriel PE, Solberg TD, Bergendahl HW, et al. Journey toward high reliability: a comprehensive safety program to improve quality of care and safety culture in a large, Multisite Radiation Oncology Department. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):480.

Zhu Q, Johnson S, Sarkis J. Lean six sigma and environmental sustainability: a hospital perspective. Supply Chain Forum: Int J. 2018;19(1):25–41.

Greenfield D, Iqbal U, Li Y-C. Healthcare improvements from the unit to system levels: contributions to improving the safety and quality evidence base. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29(3):313.

McNab D, Bowie P, Morrison J, Ross A. Understanding patient safety performance and educational needs using the “Safety-II” approach for complex systems. Educ Prim Care. 2016;27(6):443–50.

D’Andreamatteo A, Ianni L, Lega F, Sargiacomo M. Lean in healthcare: a comprehensive review. Health Policy. 2015;119(9):1197–209.

Teisberg E, Wallace S, O’Hara S. Defining and implementing value-based health care: a strategic framework. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):682–5.

Wu AW, Johansen KS. Lessons from Europe on quality improvement: report on the Velen Castle WHO meeting. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1999;25(6):316–29.

Donabedian A. The quality of care. how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743-8.3-8.

Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. 1995.

Firth-Cozens J. Cultures for improving patient safety through learning: the role of teamwork. BMJ Qual Saf. 2001;10(suppl 2):ii26–31.

Piper D, Lea J, Woods C, Parker V. The impact of patient safety culture on handover in rural health facilities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–13.

Auschra C. Barriers to the integration of care in inter-organisational settings: a literature review. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(1):5.

Lan Y, Chandrasekaran A, Goradia D, Walker D. Collaboration structures in integrated healthcare delivery systems: an exploratory study of accountable care organizations. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management. 2022.

Niemsakul J, Islam SM, Singkarin D, Somboonwiwat T. Cost-benefit sharing in healthcare supply chain collaboration. Int J Logist Syst Manag. 2018;30(3):406–20.

Aunger JA, Millar R, Greenhalgh J, Mannion R, Rafferty A-M, McLeod H. Why do some inter-organisational collaborations in healthcare work when others do not? A realist review. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):82.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to Dr Kia-Chong Chua, King's College London, UK for his very insightful contribution to the process and analysis of the review.

Funding

This work is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council, grant number ES/P000703/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Two reviewers ST and MM worked independently under the guidance of senior co-author CH. MM reviewed 5% of articles from search to synthesis, and ST 100% of all stages. Agreement in the co-review stages was over 90%. ST completed the synthesis and analysis of the review. Any disagreements were discussed with NN, BG, TS, and CH. ST wrote the manuscript, compiled all the tables and figures in this manuscript. All authors advised, reviewed, and approved the development of this manuscript, its tables, and figures.

Authors’ information

S'thembile Thusini is a PhD student, with the Health Service and Population Research Dept, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

TS received funding from Cancer Alliance and Health Education England for training cancer multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) in assessment and quality improvement methods in the United Kingdom. TS received consultancy fees from Roche Diagnostics. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests. TS research is supported by the Welcome Trust (219425/Z/19/Z) and Diabetes UK (19/0006055).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information