Abstract

Background

Antenatal care (ANC) is a service that can reduce the incidence of maternal and neonatal deaths when provided by skilled healthcare workers. Patient satisfaction is an important health system responsiveness goal which has been shown to influence adherence to healthcare interventions. This study aims to assess the determinants of pregnant women’s satisfaction with ANC across Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi using nationally representative Service Provision Assessment data.

Methods

Patient satisfaction was conceptualised mainly based on Donabedian’s theory of healthcare quality with patient characteristics, structure, and process as the major determinants. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify the potential determinants.

Results

Findings show that satisfaction was negatively associated with women’s age (AOR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.92–0.99) and having a secondary (AOR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.17–0.87) or tertiary education (AOR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.17–0.99) in Kenya. Women on their first pregnancy were more likely to report satisfaction in Tanzania (AOR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.00–2.62) while women were less likely to report being satisfied in their second trimester in Malawi (AOR: 0.31; 95% CI: 0.09–0.97). The important structural and process factors for patient satisfaction included: private versus public run facilities in Kenya (AOR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.22–3.43) and Malawi (AOR: 1.85; 95% CI: 0.99–3.43); level of provider training, that is, specialist versus enrolled nurse in Tanzania (AOR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.13–0.93) or clinical technician in Malawi (AOR: 0.08; 95% CI: 0.01–0.36); and shorter waiting times across all countries.

Conclusion

Findings highlight the importance of professional proficiency and efficient service delivery in determining pregnant women’s satisfaction with ANC. Future studies should incorporate both patient characteristics and institutional factors at health facilities into their conceptualisation of patient satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Maternal and neonatal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remains high with approximately 200,000 maternal deaths and over one million neonatal deaths per year [1, 2]. Antenatal care (ANC) is a service that can reduce the incidence of maternal and neonatal deaths when provided by skilled healthcare workers (HCWs) [3,4,5]. Since 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) has updated its recommendation to a minimum of eight ANC visits for pregnant women; up from the longstanding recommendation of four ANC visits [6]. The ANC visits should be initiated in the first trimester and include a package of services: timely and relevant health information, screening for complications, tetanus toxoid (TT) vaccinations based on previous vaccine exposure, and daily iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets. However, Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi are still following the previously recommended guidelines for four ANC visits which is only being adhered to by 52% of women in SSA [7,8,9,10]. Sub-Saharan African countries will need to increase ANC utilisation to meet the third Sustainable Development Goal which aims to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” [11].

While improving health outcomes is the primary goal of a health system, the WHO also emphasises the importance of health system responsiveness goals such as improving patient satisfaction [12]. Patient satisfaction is an indicator of healthcare quality which may be influenced by both aspects of care (e.g., technical quality) as well as personal and environmental factors that influence the patients’ views prior to the healthcare experience, which are known as antecedents (e.g., general expectations) [13, 14]. Patient satisfaction has been linked to adherence to services in the context of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and maternity care in SSA [15,16,17]. Thus, increasing satisfaction is bound to improve ANC attendance outcomes.

Conceptualisation of patient satisfaction

Donabedian’s theory of healthcare quality defines patient satisfaction as a positive evaluation of the different aspects of the quality of care [18]. This model draws information from three indicators of healthcare quality: structure, process, and outcome. Structure refers to the organisational factors at the health facility (management, administration, and financing), physical attributes (infrastructure and equipment) and staffing (HCW availability and qualifications). Process includes the actions of the provider in diagnosing conditions and recommending treatment and the actions taken by patients in seeking and carrying out personal care. Outcomes refer to patient satisfaction. However, we argue that the model fails to capture the potential antecedents of patient satisfaction; a critique supported by Coyle et al. [19].

This study primarily uses Donabedian’s conceptualisation of patient satisfaction as a guiding framework as it is widely used and is considered the most comprehensive framework for patient satisfaction [18]. Donabedian highlights the importance of, and enumerates, the structural and process related factors that are critical for patient satisfaction. However, other theories such as the ‘value expectancy model’ describe how patients’ expectations may influence patient satisfaction; the ‘multiple models theory’ further explains that these expectations are in turn predicated by social and cultural factors [20, 21]. Furthermore, the ‘multiple models theory’ highlights the importance of ‘health status’ as yet another patient related factor [21]. We have thus adapted the Donabedian model to add a third overarching determinant of satisfaction called patient characteristics; to render our guiding framework a more holistic conception of patient satisfaction (Fig. 1) [18, 21, 22].

Determinants of patient satisfaction

According to a systematic review by Batbaatar et al. (2017) which synthesised 108 international journal articles published between 1980 and 2014, the aspects of care with the greatest association with patient satisfaction, in order of importance, include: “interpersonal skills, competence, physical environment of the facility, accessibility, continuity of care, hospital characteristics, and outcome of care” [14]. However, the relationship between satisfaction and many socio-demographic characteristics remains inconclusive and may be specific to a particular country or grouping. Patient characteristics that have been shown to influence satisfaction in the ANC context in SSA include: distance to facility, marital status, income status, education, religion, prior children and health status [23,24,25,26,27,28]. However, the direction of these relationships is inconsistent across studies. In terms of structure, attending a private health facility, having regular external supervisory visits at the facility and good administration were positively associated with patient satisfaction in Kenya, as was having privacy during ANC consultations and appropriate ANC equipment in Nigeria [29,30,31]. A negative relationship between ANC provider training and satisfaction was reported in Namibia [29]. More generally, the WHO standards for maternal, newborn and child health provide eight domains for assessing the quality of care in a health system which are categorised into provision of care, experience of care and availability of resources [32, 33]. The domains relating to structure are evidence-based practices for routine care, actionable information systems, functioning referral systems, competent and motivated human resources and availability of essential physical resources.

According to Donabedian’s theory and the systematic review by Batbaatar et al. (2017), interpersonal relationships between patient and provider is the most important determinant of patient satisfaction [14, 18]. Respect, confidentially and communication between patient and provider have been highlighted as the key determinants of satisfaction in this regard in SSA [24, 25, 31, 34]. This is supported by the WHO standards for maternal, newborn and child health which include respect, preservation of dignity and protection of rights, emotional support and effective communication as key domains of quality of care [32, 33]. Furthermore, shorter waiting times are a consistent predictor of patient satisfaction in SSA and internationally [14, 29, 34]. There is also some evidence from Kenya, Ethiopia, Malawi and Nigeria to suggest that receiving medications, the number of clinical procedures performed and the number of ANC visits attended are positively associated with pregnant women’s satisfaction [25,26,27, 29, 31, 35].

To summarise, there is limited research on the determinants of patient satisfaction in the ANC context in SSA, variability in survey questionnaires affect comparability, and few studies have used a comprehensive conceptualisation of patient satisfaction which incorporate both patient characteristics and aspects of care. This study aims to identify the determinants of satisfaction in three sub-Saharan African countries (Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi) with similar geopolitcal contexts, socio-cultural norms and epidemiological traits. To this end, we analysed the Service Provision Assessment (SPA) data from the nationally representative Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) database across the three countries [36].

Methods

Setting

Three sub-Saharan African countries (Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi) with available SPA data since 2010 were selected for this analysis due to their geopolitical, socio-cultural and epidemiological similarities. While this study does not statistically compare the determinants of satisfaction across the chosen countries, it offers a comparative analysis as far as providing descriptive statistics across all three countries; and thus, it was important that the countries included in the analysis were from similar contexts [37]. The Democratic Republic of Congo and Senegal were the only other sub-Saharan African countries with available SPA data since 2010.

Geopolitically, Kenya and Tanzania are both located in east Africa while Malawi is a nearby southern central African country. All three countries have a reasonably stable democracy and are classified as low or lower-middle income economies [38]. Socio-culturally, Christianity is the predominant religion in all three countries, while Islam also has a substantive representation and plays a major role in the socio-cultural landscape in Tanzania [39, 40]. From an epidemiological perspective, the prevalence of HIV and Malaria is very high in all three countries which is particularly risky for pregnant women and neonates [41, 42]. The average maternal mortality ratio (deaths per 100, 000 live births) is similar in Kenya and Malawi (342 vs. 349), although much higher in Tanzania (524) [1]. Maternal mortality rates are lower in most southern African countries (< 300). The average neonatal mortality ratio is similar across all three countries (19.8–21 per 1000 live births) as well as many other southern African countries [43].

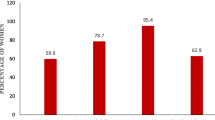

Attendance of all four ANC visits is between 51 and 64% across the three countries [10]. In Kenya and Tanzania, most ANC consultations are provided by registered nurses with a three-year degree or diploma, and enrolled nurses with a two-year diploma, who work under the supervision of a registered nurse [44,45,46]. In Malawi, most ANC consultations are provided by medical assistants who have a two-year diploma in clinical medicine [47, 48]. In some cases, clinical technicians provide care in each country by performing diagnostic tests.

Data

This study uses the most recent SPA data from Kenya (2010), Tanzania (2014–2015) and Malawi (2013–2014) available in the DHS database [36]. This data was accessed following an application to the DHS website (dhsprogram.com). The DHS Program has policies which ensure a high-quality dataset that is representative of the study population and ready for analysis. All DHS data collection procedure are compliant with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects and country-specific laws and regulations.

Service Provision Assessments are health facility surveys which measure the quality and availability of basic health services, such as those for ANC, in a country. Surveys are standardised, although the questionnaires were updated in 2012, thus the Kenyan data was collected using an older version of the questionnaire. Nevertheless, the indicators available were almost identical across the three datasets with very few exceptions, which are highlighted where they influence any observed results. The assessment is comprised of four surveys:

-

1.

The Facility Inventory Questionnaire gathers information on the availability of services, management systems, staffing, infrastructure, equipment, and medical supplies at the health facility.

-

2.

The Provider Interview records the qualifications, experience, and perceptions of HCWs regarding health service delivery at the facility.

-

3.

The ANC Observational Survey assesses the providers’ adherence to quality and health service delivery standards for ANC during consultation with a patient

-

4.

The Client Exit Interview is conducted with clients following an observation of their ANC consultation and reports on the clients’ understanding of the services provided and perceptions of the quality of care received.

Sampling

In each country, a regionally and nationally representative sample of public, private and faith-based facilities offering ANC services were randomly selected for the Facility Inventory Questionnaire [36]. As for the ANC Observational Surveys and Client Exit Interviews, these were carried out with an opportunistic sample of no more than 15 patients per facility and five per provider, based on the number of patients and providers present on the day of data collection for the Facility Questionnaire. This study utilised information from Facility, Observational and Exit Interviews. Facility and interview sampling is described for each country in Table 1 below [44, 45, 47].

Patient characteristics, structure and process

The SPA surveys provided ample indicators of patient characteristics, structure and process. Indicators of structure were selected from the Facility Inventory and Observational Questionnaires while indicators of process and patient characteristics were chosen from the ANC Observational and Exit Interviews. The selection of variables was guided by the conceptualisation of patient satisfaction adapted for this study (Fig. 1) as well as empirical evidence from a literature review of the determinants of patient satisfaction in the ANC context in SSA (Additional file 1: Appendix A). Composite additive or binary variables were created for certain aspects of structure and process; described in more detail in Table 2.

Outcomes

The study applied a similar approach to measuring patient satisfaction as Do et al. (2017) which is a composite binary variable created using patient’s responses to 11 statements regarding common problems at the health facility [29]. Patients rated these problems as major, minor or no problem (Table 3). Clients were considered satisfied if they indicated no major problems with any of the 11 statements.

Statistical analysis

The determinants of patient satisfaction were identified using a bivariate and multivariate analysis. The bivariate analysis was applied to test the independent association of patient characteristics and aspects of structure and process with patient satisfaction (Table 5). A logistic regression analysis was applied to test these associations. Independent variables with evidence of a significant association (p-value ≤ 0.05) in at least one country were included in the multivariate analysis for each country. Determinants of patient satisfaction highlighted in the systematic search (Additional file 1: Appendix A) which fitted into our conceptualisation of patient satisfaction were also included in the final model regardless of the results from the bivariate analysis. All patient characteristics were included in the final model to control for confounding, excluding urban/rural residence as this data was missing for Kenya.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed for each country with patient satisfaction as the outcome variable (Table 6). A correlation analysis was conducted to ensure that no colinear variables (r = +/− 0.8) were included in the multivariate regression analysis. All descriptive statistics and analyses were adjusted by sample weight (PSU = facility, strata = region and facility type). Missing records were excluded from analyses. The number of missing records was less than 50 per variable.

Results

Patient characteristics

In general, patient characteristics were similar in Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi (Table 4). Most women were between 20 and 35 years of age (≥ 69.72%) and had a primary school education (≥ 55.67%). However, the percentage of women with a tertiary education was notably higher in Kenya (10.91%) compared to Tanzania (1.75%) and Malawi (2.82%). Seventy percent or more of the study participants were multiparous and more than half were in their third trimester although this percentage was much higher in Kenya (71.19%) compared to Tanzania (51.61%) and Malawi (52.77%). Most women in Tanzania and Malawi lived in rural areas (72%). Finally, the percentage of women who attended the health facility nearest to their home was lower in Kenya (77.43%) compared to Tanzania (87.59%) and Malawi (90.1%). Attributes of structure and process are described in the supplementary information (Additional file 1: Appendix B and Appendix C).

Bivariate logistic regression findings

Table 5 describes the independent associations between potential determinants and patient satisfaction. Variables with a significant association with pregnant women’s satisfaction in at least one of the study countries included age, level of education, managing authority, system for recording client opinion, visual and auditory privacy, cleanliness, ANC provider training, waiting times before being seen by provider, provider inquiring about pregnancy-related problems and provision of infection control.

Multivariate logistic regression findings

The association between patient characteristics and pregnant women’s satisfaction with ANC services are notably different in Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi (Table 6). However, aspects of structure and process including managing authority, ANC provider training and waiting times had a more consistent relationship with satisfaction across the three countries.

In terms of patient characteristics, there was a negative association between satisfaction and women’s age (AOR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.92–0.99; P < 0.05) as well as women with a secondary (AOR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.17–0.87; P < 0.05) or tertiary education (AOR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.17–0.99; P < 0.05) in Kenya. Satisfaction was positively associated with attendance of a facility nearest to home in Kenya with weak significance (AOR: 1.38; 95% CI: 0.99–1.91, P = 0.05), although a statistically non-significant (P > 0.25) negative association was observed in Tanzania and Malawi. Women on their first pregnancy were more likely to report being satisfied than multiparous women in Tanzania (AOR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.00–2.62; P < 0.05) while pregnant women were less likely to report being satisfied in their second trimester compared to their first trimester in Malawi (AOR: 0.31; 95% CI: 0.09–0.97; P < 0.05).

Among the variables related to structure, attending a private rather than public health facility was associated with increased odds of satisfaction in Kenya (AOR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.22–3.43, P < 0.01) and Malawi (AOR: 1.85; 95% CI: 0.99–3.43; P = 0.05). In terms of ANC provider training, pregnant women were less satisfied when attended by an enrolled nurse in Tanzania (AOR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.13–0.93, P < 0.05), or a clinical technician (AOR: 0.08; 95% CI: 0.01–0.36, P < 0.01) and registered nurse with a diploma (AOR: 0.11; 95% CI: 0.01–1.05, P = 0.06) in Malawi, compared to a specialist medical doctor. The odds of satisfaction also decreased per item of ANC equipment available at facilities in Malawi (AOR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.54–0.82, P < 0.01).

In terms of process, waiting time had a consistently negative association with satisfaction in all three countries (P < 0.05). No other aspect of process showed a statistically significant relationship with satisfaction.

Discussion

The key findings of this study emphasise the importance of antecedents or patient characteristics that underlie pregnant women’s expectations of healthcare services as key determinants of satisfaction in Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi; although differently across the three countries. Aspects of structure and process were more consistently associated with satisfaction across the three countries, including facility managing authority (public versus private), level of provider training and shorter waiting times.

Patient characteristics

The negative association observed between age and satisfaction in Kenya is a surprising finding, as the majority of studies in the systematic review by Batbaatar et al. (2017) on the determinants of patient satisfaction in the international healthcare context have found the reverse to be true [14]. In the Kenyan case, it could be claimed that younger women may have less experience attending ANC visits for themselves or friends and family thereby lacking a benchmark by which to judge their experiences. However, it would seem more prudent to expect this relationship as being highly modulated by culture and other contextual factors. For example, Batbaatar et al. (2017) report a similar negative association from studies of satisfaction in former Soviet countries, suggesting that there might be cultural factors that undergird observed trends [14]. Batbaatar et al. (2017) further highlight some findings that suggest that relationships may not be linear, with more dynamic variabilities across different stages of a woman’s life.

There was also a negative relationship between pregnant women’s satisfaction and education in Kenya; this relationship has been inconsistent in the ANC context in SSA [26, 28]. The negative relationship between satisfaction and education was also observed by a study in Ethiopia whereby the authors explain it may be because educated women have higher expectations for ANC from being better informed [28]. The level of education was more varied in the Kenyan sample compared to Tanzania and Malawi which may have allowed the data to highlight this finding; therefore the same trend might have been observed in the other countries had the data included more women with higher education as in the Kenyan case.

In Tanzania, there was a positive association between satisfaction and being on your first pregnancy which agrees with previous studies from Rwanda and Tanzania [17, 24]. In Malawi, women in their second trimester were less satisfied compared to those in their first trimester, which is a novel finding. Women on their first pregnancy may have limited experience with ANC while women on their first trimester may have not interacted with the health system enough times to develop strong levels of dissatisfaction. In addition, women in their second trimester may feel physically and mentally different to women in their first trimester, which may influence their level of satisfaction thus highlighting the role of health status in determining patient satisfaction as described by the ‘multiple models theory’ [21].

These findings all suggest that women who have had a previous experience with ANC due to their age, a prior pregnancy, or a previous visit earlier on in their current pregnancy are less likely to be satisfied than women who had little or no experience with ANC before this visit. Furthermore, women with a higher level of education may know what to expect from ANC and are thus more difficult to satisfy. Physical and mental well-being may also influence pregnant women’s level of satisfaction, although further research is needed to explore the association between general health status and patient satisfaction. Therefore, patient satisfaction appears to be heavily influenced by patient characteristics and perceptions and expectations of the healthcare experience. Researchers and providers should consider a wide range of patient characteristics when assessing and interpreting satisfaction scores.

Additionally, patients were also more satisfied when attending a facility nearest to home in Kenya. These findings need to be gauged in view of other findings in the ANC context in SSA which found that patients travelling from more remote villages were more satisfied despite the longer journey; thereby highlighting the complexity of measuring satisfaction [14, 23, 27].

Structure and process

In Kenya and Malawi, patients were more satisfied at private versus public health facilities. These findings are consistent with several other studies in ANC and family planning settings in SSA as well as the wider healthcare context [29, 50, 51]. These studies attribute their findings to shorter waiting times in the private sector and better hospitality. Waiting times were much shorter in the private versus public sector in this study.

In Tanzania and Malawi, patients were more satisfied when attended by specialist doctors compared to ANC providers with fewer qualifications. These findings contradict earlier findings from nationally representative studies in Kenya, Namibia and Malawi which used similar methodology and found no relationship and even a negative association in Namibia [23, 29]. However, in the wider healthcare context, there is strong evidence for a relationship between perceived competency of the healthcare provider and patient satisfaction [14]. Findings suggest that patients are not satisfied with the level of competency of enrolled nurses in Tanzania, and registered nurses with only a diploma or clinical technicians in Malawi. This is a significant problem in Tanzania where enrolled nurses serve almost half of all pregnant women attending ANC. Tanzania has very high rates of maternal mortality, making the task of upskilling nurses of utmost importance [1].

There was a surprisingly negative association between satisfaction and the amount of ANC equipment available at the health facility in Malawi. This result may be a reflection of the inadequacy of our measure for availability of equipment to indicate the readiness of the facilities to deliver good service.

Only major aspects of structure and process such as managing authority, provider training and waiting times were associated with patient satisfaction in this study. This finding is not altogether surprising as a review of the theoretical literature on patient satisfaction in 1994 by Williams argued that patients tend to express dissatisfaction when a major negative event occurs [52].

Nevertheless, these findings reinforce the importance of fundamental aspects of the healthcare system including proper management of health facilities, efficient service delivery and availability of skilled HCWs. Findings suggest that improving these components in health facilities will be central to improving patient satisfaction. Future policies should pay special attention to the discrepancies between public and private facilities, particularly in Kenya and Malawi, and may consider separating their analyses by managing authority to inform policies.

Strengths and limitations

This analysis of data is guided by a contemporary conceptualisation of patient satisfaction which was based on an extensive review of the theoretical literature, as well as the empirical evidence in the ANC context in SSA. We used nationally representative SPA datasets across multiple country settings. Given the cross-sectional study design, the findings do not provide evidence for a causal relationship between determinants and satisfaction. Some factors related to socio-economic status, ethnicity and religion were not available for inclusion in this analysis but given the many other patient characteristics that were included in the final model, we are reassured that socio-demographic dimensions have been accounted for adequately. Finally, there is potential for a social desirability bias in ANC Observational Interview results as ANC consultations were conducted under observation by a data collector, but this bias should be uniform and ultimately not affect the findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, these findings underscore the importance of patient characteristics and prior experiences in influencing patient satisfaction, alongside structural and process factors. Future studies need to be comprehensive in incorporating this broad perspective and testing the interactions between personal, structural and process related factors. The findings highlight the importance of professional proficiency and management at heath facilities which further emphasise the importance of enhancing quality and efficiency of service provision across all types of facilities.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this project can be accessed following an application to the DHS website (https://dhsprogram.com/). The datasets used included Kenya: SPA, 2010; Tanzania: SPA, 2014–2015; and Malawi: SPA, 2013–2014.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Survey

- HCW:

-

Healthcare worker

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- IFA:

-

Iron and folic acid

- NA:

-

Not applicable

- PSU:

-

Primary sampling unit

- Ref:

-

Reference

- SPA:

-

Service Provision Assessment

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TT:

-

Tetanus Toxoid

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

UNICEF. Maternal mortality. 2019. https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality/. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

The World Bank. Number of neonatal deaths - Sub-Saharan Africa. 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DTH.NMRT?locations=ZG. Accessed 21 Nov 2020.

Arunda M, Emmelin A, Asamoah BO. Effectiveness of antenatal care services in reducing neonatal mortality in Kenya: Analysis of national survey data. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1328796.

Carroli G, Villar J, Piaggio G, Khan-neelofur D, Gülmezoglu M, Mugford M, et al. WHO systematic review of randomised controlled trials of routine antenatal care. Lancet. 2001;357:1565–70.

World Health Organisation. WHO antenatal care randomized trial: manual for implementation of the new model. Geneva; 2002. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42513/WHO_RHR_01.30.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. ISBN 978 92 4 154991 2. Geneva; 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Kearns A, Hurst T, Cagla J, Langer A. Focused Antenatal Care in Tanzania: Delivering individualised, targeted, high-quality care. 2014. https://cdn2.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2014/09/HSPH-Tanzania5.pdf.

Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation and Ministry of Medical Services. National Guidelines for Quality Obstetrics and Perinatal Care. Kenya; 2016. http://guidelines.health.go.ke:8000/media/National_Guidelines_for_Quality_Obstetrics_and_Perinatal_Care.pdf.

McHenga M, Burger R, von Fintel D. Examining the impact of WHO’s Focused Antenatal Care policy on early access, underutilisation and quality of antenatal care services in Malawi: A retrospective study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):295.

UNICEF. Antenatal Care. 2019. https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/antenatal-care/. Accessed 14 Sep 2020.

World Health Organisation. Health in 2015: from MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs. Geneva: Sustainable Development Goals; 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/200009/9789241565110_eng.pdf;jsessionid=103EDE90F40A89249F7CEB09BB66BB35?sequence=1

World Health Organisation. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and their Measurement Strategies. 2010. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258734/9789241564052-eng.pdf.

Ng JHY, Luk BHK. Patient satisfaction: Concept analysis in the healthcare context. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:790–6.

Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Savino MM, Amenta P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: A systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137:89–101.

Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Black WC, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Giordano TP. Examining the Link between Patient Satisfaction and Adherence to HIV Care: A Structural Equation Model. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54729.

Gupta S, Yamada G, Mpembeni R, Frumence G, Callaghan-Koru JA, Stevenson R, et al. Factors associated with four or more antenatal care visits and its decline among pregnant women in Tanzania between 1999 and 2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101893.

Kruk ME, Hermosilla S, Larson E, Mbaruku GM. Bypassing primary care clinics for childbirth: a cross-sectional study in the Pwani region, United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:246–53.

Donabedian A. The Quality of Care: How Can It Be Assessed? J Am Med Assoc. 1988;260:1743–8.

Coyle YM, Battles JB. Using antecedents of medical care to develop valid quality of care measures. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999;11:5–12.

Linder-Pelz S. Social psychological determinants of patient satisfaction: A test of five hypotheses. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:583–9.

Fitzpatrick R, Hopkins A. Problems in the conceptual framework of patient satisfaction research: an empirical exploration. Sociol Health Illness. 1983;5:297–311.

Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Amenta P. Conceptualisation of patient satisfaction: A systematic narrative literature review. Perspect Public Health. 2015;135:243–50.

Creanga AA, Gullo S, Kuhlmann AKS, Msiska TW, Galavotti C. Is quality of care a key predictor of perinatal health care utilization and patient satisfaction in Malawi? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:1–13.

Mutaganzwa C, Wibecan L, Iyer HS, Nahimana E, Manzi A, Biziyaremye F, et al. Advancing the health of women and newborns: Predictors of patient satisfaction among women attending antenatal and maternity care in rural Rwanda. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30:793–801.

Kambala C, Lohmann J, Mazalale J, Brenner S, De Allegri M, Muula AS, et al. How do Malawian women rate the quality of maternal and newborn care? Experiences and perceptions of women in the central and southern regions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:1–19.

Farrell M. Knowledge, utilization and clients’ satisfaction with antenatal care services in Primary Health Care Centres, in Ikenne Local Government Area, Ogun State, Nigeria. Ann Health Res. 2020;6:171–83.

Lakew S, Ankala A, Jemal F. Determinants of client satisfaction to skilled antenatal care services at Southwest of Ethiopia: A cross-sectional facility based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:1–13.

Chemir F, Alemseged F, Workneh D. Satisfaction with focused antenatal care service and associated factors among pregnant women attending focused antenatal care at health centers in Jimma town, Jimma zone, South West Ethiopia; A facility based cross-sectional study triangulated with qualit. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:1–8.

Do M, Wang W, Hembling J, Ametepi P. Quality of antenatal care and client satisfaction in Kenya and Namibia. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29:183–93.

Vo BN, Cohen CR, Smith RM, Bukusi EA, Onono MA, Schwartz K, et al. Patient satisfaction with integrated HIV and antenatal care services in rural Kenya. AIDS Care. 2012;24:1442–7.

Onyeajam DJ, Xirasagar S, Khan MM, Hardin JW, Odutolu O. Antenatal care satisfaction in a developing country: a cross-sectional study from Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:368.

World Health Organization. Standards For Improving Quality of Maternal And Newborn Care In Health Facilities. ISBN 978–92–4-156555–4. Geneva; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272346/9789241565554-eng.pdf?ua=1.

World Health Organization. Standards for improving the quality of care for children and young adolescents in health facilities. ISBN 978 92 4 151121 6. Geneva; 2016. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/mca-documents/advisory-groups/quality-ofcare/standards-for-improving-quality-of-maternal-and-newborn-care-in-health-facilities.pdf?sfvrsn=3b364d8_2.

Naburi H, Mujinja P, Kilewo C, Bärnighausen T, Orsini N, Manji K, et al. Predictors of patient dissatisfaction with services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:1–15.

Tafese F, Woldie M, Megerssa B. Quality of family planning services in primary health centers of Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23:245–54.

The DHS Program. Service Provision Assessments https://dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/SPA.cfm. Accessed 17 May 2020.

Goldthorpe J. Current issues in comparative macrosociology. A debate on methodological issues. Comp Soc Res. 1997;16:1–26.

The World Bank. The World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Country Classifications: Data. 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups#:~:text=Forthecurrent2021fiscal,thosewithaGNIper. Accessed 15 Aug 2020.

US Department of State. 2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: Tanzania. Office of International Religious Freedom; 2019. https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-report-on-international-religious-freedom/tanzania/.

Hackett C, Grim BJ. The Global Religious Landscape. Pew Research Center Report. 2012;1 APRIL:81. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-exec/

UNAIDS. Regions. 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/regions. Accessed 23 Aug 2020.

World Health Organization. World Malaria Report. ISBN 978-92-4-156572-1. Geneva; 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565721.

UNICEF. Neonatal mortality. 2019. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/neonatal-mortality/. Accessed 12 Nov 2020.

National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development (NCAPD) [Kenya], Ministry of Medical Services (MOMS) [Kenya], Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation (MOPHS) [Kenya], Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) [Kenya], ICF Macro. Kenya Service Provision Assessment (SPA) 2010. Kenya; 2011. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA17/SPA17.pdf.

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Tanzania Service Provision Assessment Survey 2014–2015. Tanzania; 2015. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/spa22/spa22.pdf.

East LA, Arudo J, Loefler M, Evans CM. Exploring the potential for advanced nursing practice role development in Kenya: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2014;13:33.

Ministry of Health Malawi II. Malawi Service Provision Assessment (SPA) 2013–14. Malawi; 2013. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA20/SPA20[Oct-7-2015].pdf.

Muula AS. Case for clinical officers and medical assistants in malawi. Croat Med J. 2009;50(1):77–8.

The DHS Program. DHS Service Provision Assessment Survey: ANC Client Exit Interview. 2012. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPAQ3/ANC_CLIENT_EXIT_INTERVIEW_06012012.pdf

Hutchinson PL, Do M, Agha S. Measuring client satisfaction and the quality of family planning services: A comparative analysis of public and private health facilities in Tanzania, Kenya and Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:203.

Powell-Jackson T, Macleod D, Benova L, Lynch C, Campbell OMR. The role of the private sector in the provision of antenatal care: A study of Demographic and Health Surveys from 46 low- and middle-income countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20:230–9.

Williams B. Patient satisfaction: A valid concept? Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:509–16.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The first author, KB, received funding from the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission to read the MPH at Imperial College London, during which time this manuscript was developed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research described in this manuscript was conducted by KB for her MPH dissertation at Imperial College London under the supervision of SB and HBT. SB and HBT conceptualised the initial idea which was further developed by KB. The research was conducted and written up by KB in consultation with SB and HBT who provided their expert advice on the study design, methods and interpretation of results. All authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

DHS data collection procedures ensured that all participants remained anonymous and gave informed consent to participate in DHS surveys. These procedures have been approved by the International Coach Federation Institutional Review Board (IRB) which ensures that the survey complies with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects (45 CFR 46), as well as a country-specific IRB which ensures that the survey complies with laws and norms of the nation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix A

. Systematic search strategy for journal articles from 2000 to 2020 relating to the determinants of patient satisfaction with ANC in SSA. Appendix B. Structural attributes at the health facilities analysed in Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi. Appendix C. Attributes of structure and process reported in the ANC observational and exit interviews. Appendix D. Waiting time before being seen by providers in public and private health facilities.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergh, K., Bishu, S. & Taddese, H.B. Identifying the determinants of patient satisfaction in the context of antenatal care in Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi using service provision assessment data. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 746 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08085-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08085-0