Abstract

Introduction

Female breast cancer is currently the most commonly diagnosed cancer globally with an estimated 2.3 million new cases in 2020. Due to its rising frequency and high mortality rate in both high- and low-income countries, breast cancer has become a global public health issue. This review sought to map literature to present evidence on knowledge of breast cancer screening and its uptake among women in Ghana.

Methods

Five databases (PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and EMBASE) were searched to identify relevant published studies between January 2012 and August 2021 on knowledge of breast cancer screening and its uptake among women. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews and the six-stage model by Arksey and O’Malley were used to select and report findings.

Results

Of the 65 articles retrieved, 14 records were included for synthesis. The review revealed varied knowledge levels and practices of breast cancer screening among women across a few regions in Ghana. The knowledge level of women on breast cancer screening was high, especially in breast cancer screening practice. Breast cancer screening practice among women was observed to be low and the most identified barriers were lack of technique to practice breast self-examination, having no breast problem, lack of awareness of breast cancer screening, and not having breast cancer risk. The results further showed that good knowledge of breast cancer screening, higher educational level, increasing age, physician recommendation, and household monthly income were enabling factors for breast cancer screening uptake.

Conclusion

This review showed varied discrepancies in breast cancer screening uptake across the regions in Ghana. Despite the benefits of breast cancer screening, the utilization of the screening methods across the regions is very low due to some varied barriers from the different regions. To increase the uptake of breast cancer screening, health workers could employ various strategies such as community education and sensitization on the importance of breast cancer screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is currently a global public health problem due to its increasing prevalence coupled with the high mortality rate among women in both high-income and low-income countries [1]. Female breast cancer is currently the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases in 2020 and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with 685,000 deaths [1]. Between 1990 and 2017, it was estimated that the global breast cancer cases increased by about 123.14% [2]. The GLOBOCAN cancer prediction tool estimates that by 2040 the global incidence of breast cancer cases is expected to increase more than 46% [3]. In 2012, sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) recorded about 94,378 breast cancer cases for the first time [4]. It is estimated that by 2050 the prevalence of breast cancer cases in SSA will double [5].

Globally, SSA has the highest mortality of breast cancer [1] and with less than 40% five-year survival rate, compared to high-income countries such as the United States with an 86% survival rate [4]. Whereas breast cancer mortality in many high-income countries has seen a significant decrease over the past 25 years due to increases in awareness, early detection, and treatments, it is now the leading cause of death from cancer in low-middle-income countries (LMICs) [6]. Also, mortality rates in SSA have seen an exponential increase and ranked among the world’s highest exposing the weaker health infrastructure and poor survival outcomes [1]. The low survival rates are relatively attributed to the late-stage presentation of breast cancer. Evidence from 83 studies across 17 countries in SSA revealed that 77% of all staged cases were diagnosed at stage III/IV [7] contributing to the burden in the sub-region. Because there are lack/inadequate population-based mammography screening programs in low-resource settings, efforts should be targeted at promoting early detection through breast cancer awareness, breast self-examination (BSE), and clinical breast examination (CBE) by skilled health providers, [8, 9] followed by timely and appropriate interventions to improve the survival rate in LMICs [1]. A recent study among five countries in SSA estimated that 28 to 37% of breast cancer mortalities could be prevented through earlier diagnosis and adequate treatment [10].

According to the WHO - Cancer Country Profile of Ghana 2020, breast cancer is the number one cancer among women in Ghana with an incidence of 20.4% with a relatively high mortality rate [11]. The effective way of detecting breast cancer is through regular screening [12]. Despite breast cancer screening (BCS) benefits, the utilization of BCS services is relatively low in Ghana as compared to some high-income countries [13]. A recent study conducted in Ghana revealed a relatively low BCS prevalence of 4.5% among older women [13].

Factors influencing participation in BCS services vary differently across the regions in Ghana. A recent study conducted in Ghana revealed that age, education, ethnicity, income quantile, father’s education, mother’s employment, and chronic disease status were associated with the uptake of BCS practices [14]. Another study within the country identified that accessibility and affordability of BCS services were associated with BCS uptake [15].

Hence, Ghana needs immediate action to promote early detection of breast cancer through the various screening methods as these efforts could help achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) agenda 3.4 by 2030 [16]. To promote early detection of breast cancer, women’s knowledge, attitude, and practice of BCS services are essential [17]. Evidence indicates that having knowledge of BCS practices has a positive impact on the prevention and early detection of breast cancer [17, 18]. Therefore, women’s knowledge of BCS may also have a positive influence on the attitude and practice of BCS services.

At the time of conducting this study and to the best of our knowledge, no review has comprehensively explored women’s knowledge and BCS practices in Ghana. Although a recent similar review has been conducted in SSA [17], it is important to consider and focus on the Ghanaian context. Hence, a broad perspective of understanding women’s knowledge and practice of BCS is critical to help design effective public health strategies and interventions to improve the uptake of BCS in Ghana. Thus, this review aimed to comprehensively and systematically map literature and describe the evidence on women’s knowledge and practice of BCS in Ghana.

Definitions

The Authors defined knowledge, attitude, and practice based on the framework of the World Health Organization Guide to Developing Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Surveys [19].

Knowledge: refers to the general knowledge of the various methods of breast cancer screening being utilized by Ghanaian women to enhance early detection, diagnosis, and treatment.

Attitude: refers to women’s perception or feeling or opinion about the various breast cancer screening methods to ensure early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer.

Practice: referred to the actions undertaken by Ghanaian women to utilize the various breast cancer screening methods (BSE, CBE, Mammography) to ensure early detection diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer.

Methods

This scoping review used the six stages of Arksey and O’Malley’s framework outlined in the Joanna Briggs Institute manual [20]. The Arksey and O’Malley framework [21] includes these six stages (a) identifying the research question, (b) identification of relevant studies, (c) selection of studies, (d) charting data, (e) collating, summarizing, and reporting evidence. The authors did not conduct the optional stage of consultation with stakeholders [21, 22] because of our background in the subject area. Also, this study was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [23] (Supplementary file 1).

Phase 1: Identifying research questions

The identification of research questions ensures the linkage and clarification of the study purpose and research questions [20]. The primary review question is: what evidence exists on women’s knowledge and practice of BCS in Ghana?

The following are the sub-review questions: (1) what is the evidence on the knowledge of BCS among women in Ghana? (2) what is the evidence on the practice of BCS among women in Ghana? (3) what are the barriers and predictors of BCS practices among women in Ghana?

Phase 2: Identification of relevant studies

We employed the three-step search strategy proposed by the JBI team of researchers for all types of reviews [20]. Step one ensured an initial limited search for already existing published research articles on knowledge and practice of BCS among women in Ghana. The initial limited search for potentially eligible articles was conducted in the following databases PubMed and CINAHL via EBSCOhost. The initial limited search ensured the identification of relevant keywords to be used. Step two involved a formal search after finalizing and combining the following keywords (‘breast cancer screening’, mammography OR mammogram, ‘breast self-examination’, ‘clinical breast examination’ Knowledge and practice) using the Boolean operators. The formal comprehensive and exhaustive search was conducted in the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL via EBSCOhost, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Embase. Step three adopted the snowballing technique which involved manually tracing the reference list of identified relevant studies for additional studies. This was done up to the point of saturation where no new information emanates from the subsequent manual search of articles. The detailed search strategy is shown in Table S1 in the Appendix.

Phase 3: Selection of studies

Studies included in this review were selected based on the following criteria: (a) primary studies conducted in Ghana (b) published between January 2012 to August 2021 (c) studies reporting evidence on women 18 years and above, (d) reporting evidence on knowledge and practice of BCS among women (e) articles published in the English language. The exclusion criteria were based on: (a) studies conducted in other countries but not in Ghana, (b) Studies reporting evidence in men (c) studies published before 2012 (d) studies published in the form of reports, editorials, conference paper, book chapters, and reviews (e) studies involving other cancers.

Two authors (AA and RAA) independently screened the initial titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles for relevance and inclusion. The articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The full-text evaluation was conducted among the remaining articles for inclusion. Where there were disagreements and ambiguity, VNY, AAS, and BOA assessed the article to determine the final set of studies to be included.

Phase 4: Data charting

We adapted the data extraction form for scoping reviews developed by the JBI researchers to extract data from included studies based on the purpose of this review. Using the data extraction template, two authors (AA and RAA) independently reviewed each article and discussed charted data, and update the data extraction sheet accordingly. Discrepancies and disagreements were resolved by the last author through further adjudication. The data extraction categories included first authors, publication year, study location/context, study type, aim, study population, key findings (knowledge and practice of BCS uptake).

Phase 5: Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The fifth stage of the Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework entails collating, summarizing, and reporting evidence [21]. The Braun and Clarke framework [24] was used to guide the thematic data analysis. The extracted data were read several times to make meaning after which free line by line independent coding was conducted by two authors (AA and RAA). The codes were constantly compared and discussed to resolve differences. The codes were then reviewed, and similar codes were grouped to form themes. A summary report on each theme was presented narratively with the focus on this study’s outcome of interest (knowledge, and practice of BCS).

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

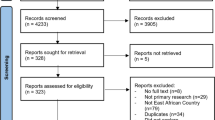

A total of 65 articles were retrieved and imported into the endnote reference manager for deduplication. After deduplication, a total of 48 articles were screened for title and abstract. A total of 14 articles [13, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] met the inclusion criteria after a full-text review of 28 articles. See a detailed PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The cumulative sample size of the 14 studies reviewed comprised 6779 females. Of the 14 studies, 12 studies [13, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33, 36, 37] employed descriptive cross-sectional study design while two studies [34, 35] used a mixed-method design. Out of the previous ten regions in Ghana, five studies were conducted in the Greater Accra region followed by three studies in the Ashanti region, two studies in the Volta region, and a study in the Northern region. One study was conducted across two regions (Greater Accra and Brong Ahafo region). Two of the studies were nationwide. Three studies [32, 35, 36] assessed women’s knowledge and practices on BSE, CBE, and mammography while six studies focused on only BSE [26, 28, 30, 31, 34, 37]. Two studies focused on BSE and CBE [27, 33] while one study focused on only mammography [29] (Table 1).

Knowledge of breast cancer screening

Among the 14 studies included, eight studies reported evidence on Ghanaian women’s knowledge of BCS practices [25, 27, 28, 30,31,32, 34, 37]. Among the various types of BCS, women reported high knowledge of BSE. A study conducted in the Ashanti region reported 95% of female nursing students’ knowledge of BSE, of which 19% of them knew mammography, 15% mentioned CBE, and 60% stated BSE as a screening method for early detection of breast cancer [37]. In the Greater Accra region, Kudzawu et al. [34] reported that 93% of women were aware of BSE. Also, in the Northern region of Ghana, it was reported that 87% of females had knowledge of BSE [28]. Another study in Greater Accra reported that more than three-quarters (76.3%) of the participants knew how to perform BSE [25]. The study by Ghansah [32] reported that 95.4% of women were aware of BSE, 69% were aware of CBE and 54% knew about screening mammography. The study conducted by Dadzi et al. [30] in the Volta region revealed a low level of women’s knowledge on BSE (43%). Participants’ main source of knowledge of BCS was from the media [28, 34, 37], healthcare providers [9, 25, 30, 34], and friends or relatives [30] (see Table 2).

Practice of breast cancer screening

This review identified three methods of BCS (BSE, CBE, and mammography) utilized by Ghanaian women. Of the 14 studies, 12 reported evidence on the practice of BSE [25,26,27,28, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Five studies provided evidence on the utilization of CBE [27, 32, 33, 35, 36]. The practice of BSE was reported a little above average among four studies with prevalence ranging from 63.3 to 77.3% [25, 28, 32, 37] while three studies recorded evidence of low practice [30, 35, 36] ranging from 27.5 to 42.6%. Among the three screening methods identified in this study, mammography had the lowest utilization rate of 13.6% [25] to as low as 1.1% [32]. Women that utilized CBE ranged from 10.2 to 38% among three studies [33, 35, 36]. Among women who practiced BSE, less than 50% of them performed BSE every month as recommended [25, 37]. Whiles studies conducted in the Volta region [30] and Ashanti region [33] of Ghana reported above 50% of once-monthly BSE practice. We also observed that some women performed BSE randomly [37] (see Tables 2, 3, and 4).

Barriers to breast cancer screening practices

Among the studies included in this review, several barriers to BCS practice were identified among women in different regions across Ghana. The most common reason why women did not perform BSE was due to the lack of technique to perform BSE [30, 34, 36]. Some women in the Volta region who reported not having breast cancer risk or did not know their risk level were less likely to perform BSE [36]. We also observed in some studies that women who did not have any breast problems opted not to have BCS [25, 30]. Some women did not practice BSE because they saw the procedure to be unnecessary [34, 37] and some also felt they had no time [37]. It was also observed that lack of awareness of BCS was a barrier to women’s uptake of any form of screening method [25]. Women who did not get a recommendation from a physician did not practice BCS [25]. We also observed that women aged 70 years and above had lower odds of having a mammogram [29] (see Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Predictors of breast cancer screening practices

This review unraveled several predictors of BCS practices among women in Ghana but the most common predictor among the studies was the woman having good knowledge of breast cancer or the screening practice [26, 27, 35]. We also observed that the increasing age of women [25, 28, 36] and higher educational level [27, 35] were significant contributory factors to the utilization of BCS in Ghana. A study conducted in Greater Accra indicated women underwent mammography screening because of routine medical check-ups [25]. It was also observed that the history of BC was also identified to be associated with the uptake of BCS among women in the Ashanti region [27], while in the Greater Accra region due to fear of death some women utilized BCS in order to ensure early detection and treatment [34]. A study by Amenuke-Edusei and Birore [25] uncovered that physician recommendation and monthly income were positive influencing factors for women utilizing mammography in the Greater Accra region. Women who had positive beliefs about breast cancer [27] and higher self-efficacy [26] were most likely to utilize BCS. A study by Agyeman et al. [13] reported that women who have ever had cervical cancer screening were more likely to screen for breast cancer (see Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to explore evidence on Ghanaian women’s knowledge and practice of BCS to inform policy and public health strategies to improve screening practices. The review revealed varied knowledge levels and practices of BCS among women across a few regions in Ghana. The knowledge level of women on BCS was exponentially high, especially in BSE practice. The finding of this study is similar to a study conducted in Nigeria where 97% of women were aware of BSE [38] but different from a study conducted in Ethiopia where only 6.6% of women heard of BCS practice and 5.2% of them knew about BCS [39]. This divergence could be due to the mass campaign carried out within Ghana on BCS uptake as most of the studies reported that women’s main source of knowledge was from the healthcare providers and the mass media.

Although we observed a high awareness/knowledge level of Ghanaian women on BCS especially BSE, this was not much reflective on the practice level of women on the various methods of BCS. We observed a little above average and low practice rates among women in Ghana. One will assume that the high awareness level seen among women would have culminated into high practice levels but that has not been the case in this review. Screening mammography was observed to be very low among women with 13.6% [25] to as low as 1.1% [32]. The evidence reported on CBE also shows a low screening rate among women in Ghana. Our study finding is not different from a recent population-based study conducted in four sub-Saharan African countries where the overall prevalence of BCS was 12.9% ranging from 5.2% in the Ivory Coast to 23.1% in Namibia [40]. Evidence from prior cohort studies based on mammography screening programs among women aged 50-69 years in high-income countries indicates a 23% reduction in breast cancer-related mortalities [41]. Several other studies have also reported screening via mammography reduces breast cancer-related deaths by 15–30% [42,43,44]. Several empirical evidence has also proven that CBE and BSE ensure early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer among women [45, 46]. As empirical evidence shows that BCS aids in the reduction in the mortalities related to breast cancer, intervention programs must be initiated to help improve the screening rate among women in Ghana to ensure early detection, diagnosis, and treatment.

We identified several factors contributing to the low prevalence rate of BCS among women in Ghana. The most identified barriers were lack of technique to practice BSE, having no breast problem, and not having BC risk. Identifying these barriers and several others will inform health care professionals and other important stakeholders on the important public health strategies and interventions to implement in order to mitigate these stumbling blocks to women patronizing BCS uptake.

Though some BCS barriers were identified, this review uncovered several factors predicting the utilization of BCS uptake among women. The prominent enabling factors include good knowledge of BCS, high education level, increasing age, physician recommendation, etc. This finding is in line with a recent study conducted in 14 low-resource countries where a higher educational level of women was found to be associated with the uptake of BCS [47]. Women with high education are more aware of health complications and adverse effects of diseases and, therefore, have regular medical check-ups as preventive measures, including BCS services. Therefore, interventions targeted to increase BCS rates may emphasize specifically on those with low educational background or may concentrate on increasing women’s health education and awareness levels to ensure population-level increases in BCS services. Another important enabling factor of BCS uptake is the increasing age of women. Contradicting this finding some studies rather found the younger age to be an enabling factor for BCS. This finding shows that educational and interventional programs should be equally targeted at both the young and old in order to promote the utilization of BCS services. We also identified that women with good knowledge of BCS were more likely to utilize BCS services. Hence improving women’s knowledge of the various BCS methods will go a long way to improve their screening behaviors.

We observed that women’s household monthly income or good socioeconomic status was a predictor of women undergoing BCS services. This finding is congruent with a study conducted in low and middle-income countries where women in the wealthier quintile were more likely to undergo BCS services than the poor [47]. Therefore, the conclusion that women with the wealthiest economic status are significantly more likely to utilize BCS services in low-resource countries also aligns with previous findings [47,48,49]. Physicians’ recommendations were also identified as an important factor for women utilizing BCS. Our finding is consistent with prior studies that reported that physician recommendations were positively associated with BCS (mammography) uptake [50, 51]. This shows the critical role physicians play in ensuring women undergo BCS, especially mammography screening.

Implications for practice, policy and research

The study revealed different prevalences, barriers, and enabling factors of BCS across the various regions. The low rate of BCS practices especially CBE and mammography screening among women across the various regions raises concerns about the health system’s readiness to address this significant back-drop. Mammography has been recognized as a gold standard for BCS in high-income countries, based on previous randomized controlled trials that observed significant reductions in the mortality rates among women aged 50 and above who participated in the organized mammography screening programs [4]. It is therefore imperative for effective awareness creation on the importance of mammography screening and its uptake. Organized mass mammography screening in various regions is needed to improve women screening uptake.

CBE is a relatively simple and inexpensive method for early detection of breast tumors [41] and can adequately be performed by trained, non-medical health workers [52]. Providing CBE at the community level and strengthening the health care system to provide these services is needed.

Ghana initiated a national strategy for cancer control for the period of 2012–2016 where the program was to create breast awareness, provide education on breast cancer prevention and BSE among girls older than 18 years. Also, health professionals were to be trained every 2 to three years to offer CBE in health facilities across the country [53, 54]. This national strategic plan has not yet been implemented [54], therefore, there is the need for the government of Ghana to implement this national policy to improve the screening practices of women and to reduce the burden of breast cancer.

Further research is recommended to assess the attitude of Ghananian women towards the various methods of BCS as the studies included in this review did not assess women’s attitudes towards screening. We recommend that the implementation of policies and public health intervention strategies targeted at improving women’s knowledge and practice towards BCS is imperative.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this review is the strict adherence to the guideline provided by Arskey and ‘O’Malley’s framework for scoping reviews [21]. Another strength of this review is the use of a comprehensive, systematic search strategy in different databases to identify relevant studies. Even though methodological rigor was applied, this review had some limitations. First, the six regions captured in this review might not be representative of the entire 16 regions in Ghana so the findings should be interpreted with caution. Also, the authors may have unintentionally omitted relevant studies from this review although extensive database and hand searches were conducted.

Conclusion

The findings from this review showed great heterogeneity in BCS prevalence across the regions in Ghana. BCS services are very important for women as it helps to reduce the burden of breast cancer where it is poorly documented especially in low and middle-income countries. Despite the benefits of BCS services, the prevalence of BCS across the regions of Ghana is very low due to some varied barriers from the different regions. The findings further showed that good knowledge of BCS, higher educational level, increasing age, physician recommendation, and household monthly income were enabling factors for BCS uptake.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BCS:

-

Breast Cancer Screening

- BSE:

-

Breast self-examination

- CBE:

-

Clinical breast examination

- MM:

-

Mammography

- LMICs:

-

low-middle-income countries

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Ji P, Gong Y, Jin ML, Hu X, Di GH, Shao ZM. The Burden and Trends of Breast Cancer From 1990 to 2017 at the Global, Regional, and National Levels: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Front Oncol. 2020;10:650.

Heer E, Harper A, Escandor N, Sung H, McCormack V, Fidler-Benaoudia MM. Global burden and trends in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(8):e1027–e37.

Black E, Richmond R. Improving early detection of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: why mammography may not be the way forward. Glob Health. 2019;15(1):3.

Cumber SN, Nchanji KN, Tsoka-Gwegweni JM. Breast cancer among women in sub-Saharan Africa: prevalence and a situational analysis. Southern African J Gynaecol Oncol. 2017;9(2):35–7.

Denny L, de Sanjose S, Mutebi M, Anderson BO, Kim J, Jeronimo J, et al. Interventions to close the divide for women with breast and cervical cancer between low-income and middle-income countries and high-income countries. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):861–70.

Jedy-Agba E, McCormack V, Adebamowo C, Dos-Santos-Silva I. Stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(12):e923–e35.

Ngan TT, Nguyen NTQ, Van Minh H, Donnelly M, O'Neill C. Effectiveness of clinical breast examination as a 'stand-alone' screening modality: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1070.

Birnbaum JK, Duggan C, Anderson BO, Etzioni R. Early detection and treatment strategies for breast cancer in low-income and upper middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(8):e885–e93.

McCormack V, McKenzie F, Foerster M, Zietsman A, Galukande M, Adisa C, et al. Breast cancer survival and survival gap apportionment in sub-Saharan Africa (ABC-DO): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1203–e12.

World Health Organisation. Cancer Country Profile Ghana: Burden of Cancer 2020 [Available from: https://www.iccp-portal.org/who-cancer-country-profiles-ghana-2020

Yurdakos K, Gulhan YB, Unalan D, Ozturk A. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of women working in government hospitals regarding breast self examination. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(8):4829–34.

Agyemang AF, Tei-Muno AN, Dzomeku VM, Nakua EK, Duodu PA, Duah HO, et al. The prevalence and predictive factors of breast cancer screening among older Ghanaian women. Heliyon. 2020;6(4):e03838.

Ayanore MA, Adjuik M, Ameko A, Kugbey N, Asampong R, Mensah D, et al. Self-reported breast and cervical cancer screening practices among women in Ghana: predictive factors and reproductive health policy implications from the WHO study on global AGEing and adult health. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):158.

Bordotsiah S. Determinants of breast cancer screening services uptake among women in the Bolgatanga Municipality of Ghana: A population-based study. 한양대학교. 2018.

Lee BX, Kjaerulf F, Turner S, Cohen L, Donnelly PD, Muggah R, et al. Transforming our world: implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J Public Health Policy. 2016;37(1):13–31.

Udoh RH, Tahiru M, Ansu-Mensah M, Bawontuo V, Danquah FI, Kuupiel D. Women's knowledge, attitude, and practice of breast self- examination in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Arch Public Health. 2020;78:84.

Atuhairwe C, Amongin D, Agaba E, Mugarura S, Taremwa IM. The effect of knowledge on uptake of breast cancer prevention modalities among women in Kyadondo County, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):279.

World Health Organization. Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control: a guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. World Health Organization; 2008. Report No.: 9241596171.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares CB, Khalil H, Parker D. Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers Manual 2015: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015. p. 3–24.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–4.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Amenuke-Edusei M, Birore CM. The Influence of Sociodemographic Factors on Women’s Breast Cancer Screening in Accra, Ghana. Adv Soc Work. 2020;20(3):756–77.

Boafo IM, Tetteh PM. Self-Efficacy and Perceived Barriers as Determinants of Breast Self-Examination Among Female Nonmedical Students of the University of Ghana. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2020;40(4):289–97.

Bonsu AB, Ncama BP, Bonsu KO. Breast cancer knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and screening efforts by micro-community of advanced breast cancer patients in Ghana. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2019;11:100155.

Buunaaim ADB-I, Salisu WJ, Hussein H, Tolgou Y, Tabiri S. Knowledge of Breast Cancer Risk Factors and Practices of Breast Self-Examination among Women in Northern Ghana. Medical and Clinical. Research. 2020;10(10):1332–45.

Calys-Tagoe BNL, Aheto JMK, Mensah G, Biritwum RB, Yawson AE. Mammography examination among women aged 40 years or older in Ghana: evidence from wave 2 of the World Health Organization's study on global AGEing and adult health multicountry longitudinal study. Public Health. 2020;181:40–5.

Dadzi R, Adam A. Assessment of knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among reproductive age women in Akatsi South district of Volta region of Ghana. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0226925.

Fiador GS. Breast Self-Examination for Breast Cancer among Female Students of. University Of Ghana: University of Ghana; 2018.

Ghansah A. Factors Influencing Breast Cancer Screening among Female Clinicians at the Ga West and Ga South Municipal Hospitals in. Accra: University of Ghana; 2019.

Gyedu A, Gaskill CE, Boakye G, Abdulai AR, Anderson BO, Stewart B. Differences in Perception of Breast Cancer Among Muslim and Christian Women in Ghana. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–9.

Kudzawu E, Agbokey F, Ahorlu CS. A cross sectional study of the knowledge and practice of self-breast examination among market women at the makola shopping mall, Accra, Ghana. Adv Breast Cancer Res. 2016;5(3):111–20.

Opoku SY, Benwell M, Yarney J. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, behaviour and breast cancer screening practices in Ghana, West Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:28.

Osei-Afriyie S, Addae AK, Oppong S, Amu H, Ampofo E, Osei E. Breast cancer awareness, risk factors and screening practices among future health professionals in Ghana: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0253373.

Sarfo LA, Awuah-Peasah D, Acheampong E, Asamoah F. Knowledge, attitude and practice of self-breast examination among female university students at Presbyterian University CollegeGhana. Am J Res Commun. 2013;1(Suppl 11):395–404.

Adetule Y. 81P Breast Self-Examination (BSE): A strategy for early detection of breast cancer in Nigeria. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:ix24.

Dibisa TM, Gelano TF, Negesa L, Hawareya TG, Abate D. Breast cancer screening practice and its associated factors among women in Kersa District, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33:144.

Ba DM, Ssentongo P, Agbese E, Yang Y, Cisse R, Diakite B, et al. Prevalence and determinants of breast cancer screening in four sub-Saharan African countries: a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e039464.

Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Bouvard V, Bianchini F, et al. Breast-cancer screening—viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2353–8.

Akuoko CP, Armah E, Sarpong T, Quansah DY, Amankwaa I, Boateng D. Barriers to early presentation and diagnosis of breast cancer among African women living in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171024.

Grosse Frie K, Samoura H, Diop S, Kamate B, Traore CB, Malle B, et al. Why Do Women with Breast Cancer Get Diagnosed and Treated Late in Sub-Saharan Africa? Perspectives from Women and Patients in Bamako, Mali. Breast Care (Basel). 2018;13(1):39–43.

Getachew S, Tesfaw A, Kaba M, Wienke A, Taylor L, Kantelhardt EJ, et al. Perceived barriers to early diagnosis of breast Cancer in south and southwestern Ethiopia: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):38.

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Thara S, Muwonge R, Prabhakar J, Augustine P, et al. Clinical breast examination: preliminary results from a cluster randomized controlled trial in India. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(19):1476–80.

Mahumud RA, Gow J, Keramat SA, March S, Dunn J, Alam K, et al. Distribution and predictors associated with the use of breast cancer screening services among women in 14 low-resource countries. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1467.

Wübker A. Explaining variations in breast cancer screening across European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(5):497–514.

Sicsic J, Franc C. Obstacles to the uptake of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings: what remains to be achieved by French national programmes? BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:465.

Boxwala FI, Bridgemohan A, Griffith DM, Soliman AS. Factors associated with breast cancer screening in Asian Indian women in metro-Detroit. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(4):534–43.

Guvenc I, Guvenc G, Tastan S, Akyuz A. Identifying women's knowledge about risk factors of breast cancer and reasons for having mammography. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(8):4191–7.

Corbex M, Burton R, Sancho-Garnier H. Breast cancer early detection methods for low and middle income countries, a review of the evidence. Breast. 2012;21(4):428–34.

Ministry of Health. National Strategy for Cancer Control in Ghana: 2012–2016. MoH Accra; 2011.

Mensah KB, Mensah ABB. Cancer control in Ghana: A narrative review in global context. Heliyon. 2020;6(8):e04564.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

The study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: AA, AS, BOA; drafting the manuscript: AA, AS, SS, VNY, RAA, JS, and BOA; revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; AA, AS, SS, VNY, RAA, JS, and BOA. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

College of Nursing, Yonsei University, 50-1, Yonsei-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03722, South Korea(AA),Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ho, Ghana(AA),College of Public Health, Medical and Veterinary Sciences, James Cook University, Australia (AS),Faculty of Built and Natural Environment, Department of Estate Management, Takoradi Technical University, Takoradi, Ghana (AS),Centre for Gender and Advocacy, Takoradi Technical University, P.O.Box 256, Takoradi, Ghana (AS),Department of Preventive Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana (VNY), Department of Midwifery and Women’s Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana (RAS),Mo-Im Kim Nursing Research Institute, College of Nursing, Yonsei University, South Korea (JS),School of Public Health, Faculty of Health, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia (BOA).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No, I declare that the authors have no competing interests as defined by BMC, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper. Abdul-Aziz Seidu is an Associate Editor for this Journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Afaya, A., Seidu, AA., Sang, S. et al. Mapping evidence on knowledge of breast cancer screening and its uptake among women in Ghana: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 526 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07775-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07775-z