Abstract

Background

To reduce maternal mortality Tanzania introduced Maternal Death Surveillance and Response (MDSR) system in 2015 as recommended by World Health Organization (WHO). All health facilities are to notify and review all maternal deaths inorder to recommend quality improvement actions to reduce deaths in future. The system relies on consistent and correct categorization of causes of maternal deaths and three phases of delays. To assess its adequacy we compared the routine MDSR categorization of causes of death and three phases of delays to those assigned by an independent expert panel with additional information from Verbal Autopsy (VA).

Methods

Our cross-sectional study included 109 reviewed maternal deaths from two regions in Tanzania for the year 2018. We abstracted the underlying medical causes of death and the three phases of delays from MDSR system records. We interviewed bereaved families using the standard WHO VA questionnaire. The obstetrician expert panel assigned underlying causes of death based on information from medical files and VA according to International Classification of Disease to Death in Pregnancy Childbirth and Puerperium (ICD-MM). They assigned causes to nine ICD-MM groups and identified the three phases of delays. We used Cohen’s K statistic to compare causes of deaths and delays categorization.

Results

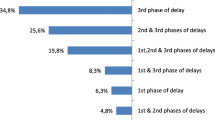

Comparison of underlying causes was done for 99 deaths. While 109 and 84 deaths for expert panel and MDSR respectively were analyzed for delays because of missing data in MDSR system. Expert panel and MDSR system assigned the same underlying causes in 64(64.6%) deaths (K statistic 0.60). Agreement increased in 80 (80.8%) when causes were assigned by ICD-MM groups (K statistic 0.76). The obstetrician expert panel identified phase one delays in 74 (67.9%), phase two in 24 (22.0%) and phase three delays in all 101 (100%) deaths that were assessed for this delay while MDSR system identified delays in 42 (50.0%), 10 (11.9%) and 78 (92.9%).The expert panel found human errors in management in 94 (93.1%) while MDSR system reported in 53 (67.9%) deaths.

Conclusions

MDSR committees performed reasonably well in assigning underlying causes of death. The obstetrician expert panel found more delays than reported in MDSR system indicating difficulties within MDSR teams to critically review deaths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the past decade, maternal mortality has decreased worldwide during the period that the international community was striving to attain Millennium Development Goal 5 [1, 2]. Accelerated and concerted efforts are needed to reach the ambitious Sustainable Development Goal 3 [1, 3]. Currently, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Tanzania is still one of the highest in the world, with most deaths occurring during the intrapartum and immediate postnatal period [4, 5]. To design targeted interventions, data are needed on cause of death as well as underlying factors of three phases of delays. For this purpose the World Health Organization (WHO) has conceptualised the Maternal Death Surveillance and Response (MDSR) system to ensure that local data are available in timely fashion to steer efforts to reduce MMR.

The MDSR system, introduced since 2015 in Tanzania [6], includes identification, notification and review of maternal deaths to stimulate learning from what went wrong. Typically a team of health professionals and local managers review circumstances of deaths, underlying (sometimes called primary medical) causes and contributing factors such as delays in care seeking and provision. The three-delay model provides a conceptual framework to categorize delays in maternal death [7,8,9,10]. After completing reviews with analysis and interpretation of data, the team elaborates recommendations for action [11]. The action plans are tailored to address specific underlying medical causes of death and the contributing medical and non-medical factors. To decide on the most adequate strategies, it is important for the MDSR system to record correct and consistent causes of death according to ICD-MM [12].

Medical files are widely used to determine underlying causes of facility maternal deaths. In view of poor documentation of medical files in health facilities [13,14,15] or in instances when medical records are not available, such as death at home verbal autopsy (VA), is increasingly viewed as an alternative method of standardised interviews with bereaved families [16,17,18]. Using multiple sources may provide a more complete understanding of the circumstances of death and its causes.

Accurate categorization of causes of death facilitates implementation of recommendations that are specific to prevent maternal deaths and reduce possibilities of under- or overestimation of data. While cause of death assignment by health professionals as part of MDSR reviews is commonly preferred, challenges are reported.

In view of the importance of correct information of cause of deaths as well as contributing factors to inform strategies, we sought to 1) estimate completeness of reporting of facility maternal deaths and 2) compare categorization of medical causes using ICD MM and 3) three phases of delays to maternal deaths between the MDSR system and an expert panel of independent obstetricians. We aimed to identify existing gaps in categorizing correct underlying medical causes and three phases of delays to derive recommendations to improve the MDSR system.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted including 132 maternal deaths from two regions in Tanzania. The deaths had occurred between 1st January and 31st December 2018. Routine MDSR categorization of cause of deaths and the three phases of delay was compared with those assigned by an independent expert panel of obstetricians with additional information from VA. To compute the completeness of maternal deaths reported by the MDSR we used the number of infants that received Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine,as a proxy for live births as previously recommended, [19] to calculate the MMR for the two regions in 2018.

Study setting

The study was conducted in Lindi and Mtwara regions in Southern Tanzania with a total population of about 2 million [20]. The two regions have two regional referral hospitals, 12 district hospitals, four private/mission hospitals, 40 health centres and 399 dispensaries. The MMR in Lindi and Mtwara was 456 and 579 per 100,000 live births in 2013 [21]. The fertility rate is one of the lowest (3.8) in Tanzania. Most women, 80.8% in Lindi and 81.3% in Mtwara give birth in health facilities (dispensary, health centres and hospitals). Caesarean section rates are 6.0% in Lindi and 10.3% in Mtwara [5].

The MDSR system in Tanzania and categorization of cause of death

Each health facility that provides delivery services in Tanzania has a standard MDSR committee as stipulated in the guideline [6]. In regional and district hospitals, where most deaths occur, MDSR committees are composed of a multidisciplinary team of clinical and non-clinical staff such as obstetricians (if available), medical doctors, clinical officers, nurses and midwives from maternity wards, facility management, laboratory personnel and other supporting staff. The committee meets within 7 days after a suspected maternal death has occurred. Before the meeting, a designated person prepares a narrative summary using information from medical files, interviews of health care providers and relatives who cared for the woman. There is no clear guide on how and which relatives should be interviewed. During the meeting the summary is discussed and when necessary more information is obtained from medical files or health care providers who cared for the woman. Findings from the meeting are summarised in a maternal death reporting form which includes demographic characteristics, medical information, underlying medical cause of death, description of contributing medical and non-medical factors along the three phases of delays and a plan of action [6]. The MDSR guideline recommends the underlying medical cause of death to be categorized following ICD MM rules, but the training and the guideline does not provide a formal training on this. The reporting form in MDSR guideline has a short list of example of causes and ICD 10 codes to be used during reporting. (See Table 6 in Appendix).

Outcomes

Our main outcome was the underlying medical cause of death defined as disease or condition that started the chain of events that led to death e.g. postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) [12] . Underlying causes of deaths are grouped into nine groups that are mutually exclusive, totally inclusive and descriptive of all underlying causes of maternal deaths. The groups are; 1) Pregnancy with abortive outcome, 2) Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium, 3) Obstetric Haemorrhage 4) Pregnancy related infection, 5) Other obstetric complications, 6) Unanticipated complications of management, 7) Non-obstetric complications, 8) Unknown/undetermined and 9) Coincidental causes.

As stipulated in Tanzania MDSR guideline, delays in health care seeking or provision of care deemed to have contributed to the maternal deaths were grouped using the three delays model, stipulating delays 1) to decide to seek care; 2) to reach health facilities for care including transport and 3) to receive appropriate care in facilities [6]. Several delays may contribute to one death. Phase one delays are delays at household and personal level that lead to late or lack of seeking care. It includes the time from the onset of disease at home until the decision to seek care is made by the woman, family or both. Phase two delays are concerned with access to health care such as availability of health facility, roads and transport issues, and constitute time from when the decision to seek care is made until arrival to proper health facility. Phase three delays occur in health facilities and are more concerned with time, equipment and supplies, structure, management errors, human resources and referral system, and constitutes time from admission until adequate treatment or care begins.

Data sources and measurements

Data collection followed three steps: 1) abstracting information from MDSR documents 2) performing VA and 3) independent obstetrician panel review.

The first author AS, in close collaboration with regional Reproductive and Child Health Coordinators, abstracted information using a pre-defined checklist from maternal deaths narrative summaries, death review report forms and district monthly death report summaries (date of death, age, facility, village and cause of death).

The field team (AS and VA interviewers) then traced families using demographic information such as names of the deceased woman, place of death, district and date of death, home address, name of village/street leader, name of husband/partner and other information, for VA interviews.

Verbal Autopsy interviews were conducted using the translated standard questionnaire provided by WHO [18]. The questionnaire was piloted and the Swahili translation was reviewed and corrected accordingly. In addition to the standard inquiries, questions relating to the three phases of delay were added.

The field team commenced the process of finding families for VA interviews by visiting and enquiring in the facility where death occurred or where the deceased woman attended antenatal clinic. They were then taken to the family through local government leaders. At the family’s home, after being introduced they explained in detail the purpose of VA. Then one of the interviewers identified person (s) that was (were) present during illness and death and conducted VA with them.

Using the coded VA questionnaires as well as copies of available medical files a group of experts, consisting of three experienced obstetricians in MDSR reviewed all maternal deaths. Two of them were from Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences and had never worked in the regions and one was from Mtwara regional hospital. The latter was included to help the panel understand the context better especially information in VA. The author, AS, was among the panel members and had previously been trained on using ICD-MM. All the three panel members neither conducted the VA interviews nor documented any information from the reviews.

The three panel members reviewed all the deaths together by reading through the information in VA questionnaire and available medical files. Then they discussed the findings and made their decision by consensus. The cause of death was agreed if at least two of the panel members said the same cause of death. First, the expert panel went through VA questionnaires and determined the underlying cause from the information by consensus. Second, the panel went through the medical files and reviewed all available information. Based on these two sources, the panel determined the 1) underlying cause of death including the ICD coding, 2) contributing medical causes and 3) three phases of delays, all by consensus [12]. The three panel members reached consensus in all deaths that were reviewed even though there was a plan to consult another obstetrician in case of no agreement. This was never used since there was consensus in all deaths.

Quantitative variables

Data were processed using MS Excel and then transferred to SPSS computer program version 25. Proportions of each underlying medical cause categorized by MDSR system and the expert panel of obstetricians were computed. Underlying medical causes and differences between the routine MDSR system and obstetricians panel were tabulated. As the routine MDSR system used a shortlist of ICD codes while the expert panel used the full number of ICD-MM codes and groups, comparison had to use a pragmatic approach. For example, when the obstetricians panel categorized a death to be caused by PPH due to atony, coagulopathy or retained placenta, this was considered to be in agreement if MDSR system categorized the same death as PPH (non traumatic). Also PPH (traumatic) for MDSR system was decided to be in agreement if obstetricians’ panel categorized the same case as PPH (vaginal tear, cervical tear, extension of uterine incision during caesarean section).

Statistical methods

Cohen’s K statistics were used to determine the level of agreement in categorizing the underlying causes and the three phases of delays. We defined < 0 as no agreement, 0–0.2 as slight agreement, 0.21–0.4 as fair, 0.41–0.6 as moderate, 0.61–0.8 as substantial and 0.81–1 as almost perfect agreement [22].

Results

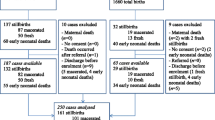

In the year 2018, a total of 132 maternal deaths were reported in the study regions. According to District Health Information System, the total number of children that received BCG vaccine (as a proxy for live-births) for that year in the two regions was 96,265. Thus according to the MDSR system, MMR was 137 per 100,000 live births with 95% Confidence Interval of 115 to 163 deaths per 100,000 live births. Our final analysis included 109 deaths (Fig. 1). Comparison of causes of death was done for 99 deaths while delays were analysed in 109 and 84 deaths for expert panel and MDSR respectively.

Flow chart of maternal deaths included in the study. Our final analysis included 109 deaths. VA was performed for 106(92.9%) deaths and medical files of 91(83.5%) women could be traced. Piloting our approach was done based on seven maternal deaths which were later excluded from analysis. Of the 132 deaths, 10 were community deaths and no clinical records were available. The recording of one death was so minimal that no information to trace the family was available. Three facility deaths were identified in the field in which two of them were identified during visits to the community and one was reported by the district health office but not reported by the routine regional MDSR system. Out of the 8 deaths that could not be traced for VA, 4 were because the demographic information was not sufficient to trace the family in the villages. The other 4 deaths were reported in the regional MDSR data but, there was no record in facility data. It was later revealed that these were suspected maternal deaths that were reported anonymously to the region but the regional office did not follow them up to confirm whether they were maternal deaths (Fig. 1)

More than half 65(59.6%) of women who died were ≥ 30 years (median 31 years and Inter-quartile range of 25–36), 64(58.7%) had primary education, 76(69.7%) were married/living with partner and 69(63.3%) were peasants. Most 52(47.7%) women were sick for less than a day and 56 (51.4%) died within 24 h of delivery. More than three quarters died in the postpartum period, more than half 65 (70.6%) had a live-born baby before dying and 56 (60.2%) gave birth by caesarean section, 49 (45%) of deaths were reported in district hospitals and 20 (18.3%) in regional hospitals (Table 1).

Traumatic and non-traumatic PPH was the most common cause of death categorized by both groups. Obstetricians panel and MDSR system categorized the same underlying causes in 64/99 (64.6%) maternal deaths (K statistic 0.60, moderate agreement) (Table 2).

The obstetricians’ panel categorized 21 deaths as caused by hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium and 15 agreements occurred with the MDSR system. The MDSR system categorized two of these deaths in group 3 (obstetric Haemorrhage), two in group 4 (pregnancy-related infection), one in group 5 (other obstetric complications) and one in group 7 (non-obstetric complications). Overall, out of 99 deaths both obstetricians` panel and MDSR system categorised 80(80.8%) in the same ICD-MM group (K statistic 0.76, substantial agreement) (Table 3).

The obstetricians’ panel identified more delays in all three categories than the MDSR system There was high percentage agreement in identification of phase-three delays 73 (86.9%) while there was slight agreement in specifying phase-two and phase one delays (K statistic 0.2) (Table 4).

“Delays in decision-making” was the predominant phase-one delay according to the obstetricians’ panel 57 (77.0%) and MDSR system 23 (54.8%). In phase two delays, MDSR system identified more 6 (60.0%) “Delayed arrival to health facility” than obstetricians’ panel 10 (41.7%). The obstetricians’ panel indicated that human errors and mismanagement was assessed to occur in 94 (93.1%) of maternal deaths as compared to 53 (67.9%) by the MDSR system. Agreement in identifying delays ranged from no agreement to slight in most of the categories. There was moderate agreement (K statistic 0.41) in identifying delayed referrals (Table 5).

Discussion

Main findings

We report a moderate agreement of the categorization of underlying causes of maternal deaths assigned by the standard MDSR committee compared with those assigned by an independent expert panel of obstetricians supported with additional information from VAs. Both groups assigned the same underlying medical cause in 64.6% of deaths. Substantial agreement (K statistic 0.76) was found when ICD-MM groups were compared.

Phase-one delays were identified in 68%, phase-two in 22% and phase-three in 100% by the obstetrician panel as compared to delays in 50% (1st delay), 12% (2nddelay) and 93% (3rd delay) identified by the MDSR system. The obstetrician panel found that human errors or mismanagement had occurred in 93.1% of deaths while the MDSR system reported this in 67.9% of deaths with moderate agreement in identifying delays in referral system. The MMR in the two regions was estimated at 137 per 100,000 live births.

Assigning underlying cause

Both, the obstetricians’ panel and the MDSR system assigned PPH as the most common underlying cause of death. Overall there was substantial agreement in categorizing the underlying cause of death and the ICD-MM group of causes with high K statistic of 0.76. This is in contrast with other studies in Sub Saharan Africa and the US, that have shown significant differences when researcher- assigned causes of death were compared with health care providers’ [23,24,25,26]. The substantial agreement in our study could be due to the national training of the MDSR committees on the use an ICD10 shortlist and orientation on ICD 10 codes.

Although most deaths were categorized similarly, the routine MDSR system still reported some contributing causes such as hypoxia, intracerebral hemorrhage, and hemorrhagic shock as underlying causes. This also has been observed in Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, South Africa and Zimbabwe where contributing or immediate causes were indicated as the underlying causes [25]. This highlights the importance of training providers of the definition of underlying cause of death. This definition can be used differently on the same death depending on the setting as it was the case in a study done in UK and the Netherlands. The study found the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths and the Dutch Audit Committee Maternal Mortality and Morbidity categorized different underlying cause for the same death due to differences in interpretation of the underlying cause and the health system approach to prevention of death [27].

Identifying the three delays

The obstetricians’ panel identified more delays in phase one (68%) and phase three (100%) compared to the MDSR system. It is of note that the MDSR system indicated no phase-three delays (provider factors) in six maternal deaths while the obstetricians’ panel identified phase-three delays in all deaths. It was not clear whether the MDSR system could not identify delays or efforts tried to shift blame to the deceased women. A culture of blame is one of the major obstacles in maternal death reviews [28, 29]. The obstetricians’ panel indicated human errors in management, substandard decision-making, mismanagement and poor skills in performing medical procedures. These may have led to complications and ultimately to death. In contrast, the routine MDSR system was less inclined to indicate such errors and did not report errors in management in most cases that led to death. Other studies have proposed that most maternal deaths occur due to delays in medical care while delays in seeking care are less important [23, 30,31,32,33]. Since Tanzania is seeing increased facility utilization and facility births, it is imperative for health care providers to identify substandard care that can be addressed to save lives [5].

Maternal death data

The two regions reported a total of 122 facility- and 10 community-related maternal deaths for the year 2018. This corresponds to a MMR of 137 per 100,000 live births, which falls short of most recent national and international estimates of 556/100,000 and 524/100,000 respectively [4, 5]. It points to under-reporting of maternal deaths most likely due to missed deaths both in the facility and community.

Underreporting of deaths was also revealed during our field activities as we identified three facility deaths that were not reported to higher levels of the health care system. Furthermore, four deaths had no records in facilities where they were reported to have taken place and had not been reviewed. This shows existing inconsistencies in identification, notification and reporting of maternal deaths in facilities. The problem of underreporting of maternal deaths is universal all over the world even in countries with well-developed vital registration systems. Studies in the United States, France, Taiwan and Netherlands have all revealed underreporting of maternal death in the health system [34,35,36,37]. The situation is also true in low and middle income countries where there is missing or late notification and reporting of maternal deaths in health system [38, 39]. The main reasons for underreporting reported in both high and low income countries are misclassifications, missing death in early pregnancy and abortion, missing indirect deaths, incomplete feeling of death certificates and missing deaths outside facilities.

Strength and limitations

The main strength of this study is the use of an expert panel consisting of experienced obstetricians who have knowledge of both ICD-MM and MDSR. All three obstetricians received explicit training and have taken part in MDSR in their home institutions. The study used data previously documented, thus the committees did not have prior knowledge of the study which removed social desirability bias if data collection would have been done prospectively.

The expert panel was supported with additional information from the VA. Using both VA and medical files ensured that the expert panel had enough information to identify underlying causes and delays. The fact the VA was used, and thus community factors were explicitly investigated, could possibly explain more delays in first phase identified by the expert panel. However, it is also difficult to know how much information was sought from the family by the MDSR committees. The committees are required to seek information from family members even though there is no formal tool such as VA questionnaire to guide that process.

This study adds to the body of evidence of the reliability of cause of deaths assignment by MDSR teams. Most other studies have assessed how well the providers categorize the underlying medical causes of death in comparison to an external expert panel or computer programs using ICD 10, thus two other systems with major limitations. Our strategy to enhance the work of the expert committee with VA is likely to have led to a more robust assignment of the cause of deaths, thus comparing with a likely gold standard.

Main limitation is the fact that there were multiple MDSR committees that reviewed the deaths. This could pose a problem for Cohen’s K statistic which is recommended for comparing two raters. But each death was reviewed by one MDSR committee and one panel, indicating a two-way comparison for each case. Also, the nature of the study led to missing of some data due to lost documentation, but VA helped in filling information gap in some of these cases.

Another limitation is that only facility deaths were included. While community deaths ought to be reported, the MDSR system is not clear on how these deaths are to be reviewed. In addition, there are no available summaries, review information or any other information about circumstances that would have been needed to include these deaths in our study. It is important to note that the distribution of causes of deaths is not representative for the total population in the two regions.

Conclusions

The MDSR system performed reasonably well in assigning the underlying cause of deaths according to ICD-MM in contrast to what other studies have indicated. The obstetricians’ panel found more delays of care provision than reported in the MDSR system, indicating difficulties within MDSR committees to critically review maternal deaths. The committee members should have training and support in identifying lessons to be learned in facilities and avoid shifting of blame to the family and deceased.

Availability of data and materials

Data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the first author on request.

Abbreviations

- ICD-MM:

-

International Classification of Disease on Death in Pregnancy, Childbirth and Puerperium

- MDSR:

-

Maternal Death Surveillance and Response

- MMR:

-

Maternal Mortality Ratio

- PPH:

-

Postpartum Hemorrhage

- VA:

-

Verbal Autopsy

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller A-B, Gemmill A, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN maternal mortality estimation inter-agency group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–74.

Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, Heuton KR, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):980–1004.

Nyasimi M, Peake L. Review of Targets for The Sustainable Development Goals: The Science Perspective; 2015. p. 31–4.

World Bank. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017 : Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Washington, D.C: World Bank Group; 2019.

Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC), [Tanzania Mainland, Ministry of Health (MoH) [Zanzibar],National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS) and ICF. 2015-16 TDHS-MIS Key Findings. Rockville: MoHCDGEC, MoH, NBS, OCGS, and ICF; 2016.

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response guideline. Dar es Salaam: Reproductive and Child Health section; 2015.

World Health Organization. Maternal death surveillance and response: technical guidance information for action to prevent maternal death. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Calvello EJ, Skog AP, Tenner AG, Wallis LA. Applying the lessons of maternal mortality reduction to global emergency health. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(6):417–23.

Danel IG, Graham WJ, Borma T. Maternal death surveillance and response. Bull World Health Organisation. 2011;89:779.

Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–110.

The Partnership for Maternal Newborn & Child Health. A Global Review of the Key Interventions Related to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (Rmnch ). Geneva: PMNCH; 2011.

World Health Organisation. The WHO Application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: ICD-MM. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

Saravi BM, Asgari Z, Siamian H, Farahabadi EB, Gorji AH, Motamed N, et al. Documentation of medical records in Hospitals of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences in 2014: a quantitative study. Acta Inform Med. 2016;24(3):202–6.

Soto CM, Kleinman KP, Simon SR. Quality and correlates of medical record documentation in the ambulatory care setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2002;2(1):22.

Tajabadi A, Ahmadi F, Sadooghi Asl A, Vaismoradi M. Unsafe nursing documentation: A qualitative content analysis. Nurs Ethics. 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019871682.

Jafarey SN, Rizvi T, Koblinsky M, Kureshy N. Verbal autopsy of maternal deaths in two districts of Pakistan--filling information gaps. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27(2):170–83.

Chandramohan D, Rodrigues LC, Maude GH, Hayes RJ. The validity of verbal autopsies for assessing the causes of institutional maternal death. Stud Fam Plan. 1998;29(4):414–22.

World Health Organization. Verbal autopsy standards: The 2016 WHO verbal autopsy instrument. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Songane FF, Bergström S. Quality of registration of maternal deaths in Mozambique: a community-based study in rural and urban areas. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(1):23–31.

United Republic of Tanzania URT. 2012 Population and housing census: population distribution by administrative areas. Dar es Salaam: National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance, Office of Chief Government Statistician President’s Office, Finance, Economy and Development Planning Zanzibar; 2013.

The United Republic of Tanzania. Mortality and Health. Dar es Salaam: National Bureau of Statisistics Tanzania, Ministry of Finance, Office of chief and Government Statistician; 2015.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Geller SE, Koch AR, Martin NJ, Prentice P, Rosenberg D. Comparing two review processes for determination of preventability of maternal mortality in Illinois. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(12):2621–6.

Mgawadere F, Unkels R, van den Broek N. Assigning cause of maternal death: a comparison of findings by a facility-based review team, an expert panel using the new ICD-MM cause classification and a computer-based program (InterVA-4). BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;123(10):1647–53.

Ameh C, Adegoke A, Pattinson R, van den Broek N. Using the new ICD-MM classification system for attribution of cause of maternal death—a pilot study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121(s4):32–40.

Owolabi H, Ameh C, Bar-Zeev S, Adaji S, Kachale F, van den Broek N. Establishing cause of maternal death in Malawi via facility-based review and application of the ICD-MM classification. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121(4):95–101.

van den Akker T, Bloemenkamp KWM, van Roosmalen J, Knight M. Classification of maternal deaths: where does the chain of events start? Lancet. 2017;390(10098):922–3.

Bӧttcher B, Abu-El-Noor N, Aldabbour B, Naim FN, Aljeesh Y. Maternal mortality in the Gaza strip: a look at causes and solutions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):396.

Smith H, Ameh C, Godia P, Maua J, Bartilol K, Amoth P, et al. Implementing maternal death surveillance and response in Kenya: incremental progress and lessons learned. Glob Health: Sci Pract. 2017;5(3):345–54.

Pembe AB, Paulo C, D’mello BS, van Roosmalen J. Maternal mortality at muhimbili national hospital in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania in the year 2011. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):320.

Merali HS, Lipsitz S, Hevelone N, Gawande AA, Lashoher A, Agrawal P, et al. Audit-identified avoidable factors in maternal and perinatal deaths in low resource settings: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):280.

Magoma M, Massinde A, Majinge C, Rumanyika R, Kihunrwa A, Gomodoka B. Maternal death reviews at Bugando hospital North-Western Tanzania: a 2008–2012 retrospective analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):333.

Muchemi O, Gichogo A. Maternal mortality in Central Province, Kenya, 2009-2010. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17:201.

Schuitemaker N, Van Roosmalen J, Dekker G, Van Dongen P, Van Geijn H, Gravenhorst JB. Underreporting of maternal mortality in the Netherlands. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(1):78–82.

Wu T-P, Huang Y-L, Liang F-W, Lu T-H. Underreporting of maternal mortality in Taiwan: a data linkage study. Taiwanese J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54(6):705–8.

Horon IL. Underreporting of maternal deaths on death certificates and the magnitude of the problem of maternal mortality. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):478–82.

Bouvier-Colle M-H, Varnoux N, Costes P, Hatton F. Reasons for the underreporting of maternal mortality in France, as indicated by a survey of all deaths among women of childbearing age. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20(3):717–21.

Abouchadi S, Zhang W-H, De Brouwere V. Underreporting of deaths in the maternal deaths surveillance system in one region of Morocco. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188070.

Mutsigiri-Murewanhema F, Mafaune PT, Juru T, Gombe NT, Bangure D, Mungati M, et al. Evaluation of the maternal mortality surveillance system in Mutare district, Zimbabwe, 2014-2015: a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:204.

Acknowledgements

Lindi and Mtwara Regional Medical Officers (Dr Genchwele M and Dr. Sichwale A), Regional RCHCos (Sr Arope R and Mr. Chibanji N), All district RCHCos, All District Medical Officers, VA interviewers (Mr Mnamala A and Mr. Fakih S) and obstetricians panel (Dr Furaha A and Dr. Kisambu L), Sida, MUHAS, UU.

Authors` contributions

All authors were involved during the planning of this study. AS did all field activities, data entry, management and analysis with close supervision of CH, SM and ABP. CH and MM helped with guidance of analysis of data, and were involved in all stages of the study. AS prepared the first draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding of the study came from Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) through bilateral cooperation with Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) and Uppsala University (UU). Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences ethical board. Permissions were obtained from Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children, President’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government, Regional Medical Officers, District Medical Officers and facility In-charges. Interviews were conducted in a calm place with enough audio secrecy and it was tape recorded with the respondents` consent. A verbal and written consent was signed by respondents before VA interview. The respondents were assured they can stop and drop out anytime during interview. During the interview some respondents became emotional and started crying. The interviewers were explained to understand and let respondent grieve without interference since they were not trained on psychological support. The interview was halted until the respondent stopped the emotional response and was then asked if they wanted to continue with the interview. All agreed to continue.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Said, A., Malqvist, M., Pembe, A.B. et al. Causes of maternal deaths and delays in care: comparison between routine maternal death surveillance and response system and an obstetrician expert panel in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res 20, 614 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05460-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05460-7