Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy is prevalent among hospitalized older adults, particularly those being discharged to a post-care care facility (PAC). The aim of this randomized controlled trial is to determine if a patient-centered deprescribing intervention initiated in the hospital and continued in the PAC setting reduces the total number of medications among older patients.

Methods

The Shed-MEDS study is a 5-year, randomized controlled clinical intervention trial comparing a patient-centered describing intervention with usual care among older (≥50 years) hospitalized patients discharged to PAC, either a skilled nursing facility (SNF) or an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IPR). Patient measurements occur at hospital enrollment, hospital discharge, within 7 days of PAC discharge, and at 60 and 90 days following PAC discharge. Patients are randomized in a permuted block fashion, with block sizes of two to four. The overall effectiveness of the intervention will be evaluated using total medication count as the primary outcome measure. We estimate that 576 patients will enroll in the study. Following attrition due to death or loss to follow-up, 420 patients will contribute measurements at 90 days, which provides 90% power to detect a 30% versus 25% reduction in total medications with an alpha error of 0.05. Secondary outcomes include the number of medications associated with geriatric syndromes, drug burden index, medication adherence, the prevalence and severity of geriatric syndromes and functional health status.

Discussion

The Shed-MEDS trial aims to test the hypothesis that a patient-centered deprescribing intervention initiated in the hospital and continuing through the PAC stay will reduce the total number of medications 90 days following PAC discharge and result in improvements in geriatric syndromes and functional health status. The results of this trial will quantify the health outcomes associated with reducing medications for hospitalized older adults with polypharmacy who are discharged to post-acute care facilities.

Trial registration

This trial was prospectively registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02979353). The trial was first registered on 12/1/2016, with an update on 09/28/17 and 10/12/2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Polypharmacy and geriatric syndromes

Polypharmacy, defined as taking five or more medications, is common among older patients [1,2,3,4]. Studies have shown that approximately 45% of hospitalized older patients are discharged on five or more medications [5,6,7]. Older patients have an increased prevalence of multi-morbidity; thus, it is not surprising polypharmacy is prevalent. However, a substantial number of medications prescribed to older patients may be unnecessary. More than 90% of inpatients are taking at least one inappropriate medication and up to 43% of medications taken by older patients lack a clear indication. Moreover, 5 to 11% of medications may be unintentionally prescribed for the same indication [8, 9]. Even when a clear indication exists, medications may be inappropriate when considering drug-drug or drug-disease interactions [10, 11]. These medications, also known as potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), have been defined by multiple explicit criteria such as the Beers list [12], the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP) [13, 14] and variations of STOPP [15]. Beyond medical appropriateness, some medications may be costly or have inconvenient dosing that decreases patient adherence [8, 9]. Finally, prescribed medications may be inconsistent with a patient’s goals of care [16, 17].

The prevalence and inappropriateness of polypharmacy may lead to multiple harmful outcomes among older community-dwelling and hospitalized populations. These outcomes include, but are not limited to, medication non-adherence [18], adverse drug events [18,19,20], and increased health care utilization and costs [21,22,23,24]. Polypharmacy and a variety of drug indices that quantify drug burden have additionally been associated with the development of geriatric syndromes [25, 26]. Notably, polypharmacy is associated with long-term cognitive impairment [27,28,29], delirium [30, 31], falls [1, 32,33,34,35,36] frailty [36,37,38], urinary incontinence [39,40,41], and unintentional weight loss [42,43,44].

A recently published study identified specific medications associated with geriatric syndromes [45]. This study showed that hospitalized older patients were prescribed a median of 6 medications per person that could be causing or exacerbating one or more geriatric syndromes. In a study of 904 hospitalized patients aged 65 and older, who were discharged to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), 57% endorsed three or more geriatric syndromes and 80% endorsed two or more syndromes [46]. The results of this same study showed that 98% of these older inpatients were prescribed 5 or more medications (polypharmacy) and 83% were prescribed 10 or more, sometimes referred to as ‘hyper-polypharmacy’. The average total number of medications at the point of the transition from the hospital to SNF was 13.8 (± 4.9) per patient. Similar to polypharmacy, the presence of multiple geriatric syndromes is predictive of poor health outcomes, even when controlling for age and illness severity [47]. Moreover, patients discharged from the hospital to SNF are at higher risk for loss of independence relative to patients discharged home [48,49,50].

Interventions to deprescribe medications and knowledge gaps

In recognition of the potential harms of polypharmacy, numerous studies have evaluated efforts to improve medication prescribing practices for older patients [51,52,53,54,55]. Most interventions have applied the use of explicit criteria to reduce inappropriate prescribing for specific medication classes utilizing tools such as the Beers list or STOPP criteria, while only a few have considered other patient-centered factors (e.g., cost, convenience, life expectancy). Previous trials have commonly used pharmacists, physicians or inter-professional teams to implement deprescribing protocols [52,53,54]. However, there are several important gaps in our current knowledge. First, few interventions have been initiated in the hospital setting, and no interventions have deprescribed across the continuum of acute and post-acute care [54, 56,57,58,59]. Second, few trials have incorporated patient preferences into the decision-making process [60,61,62,63]. Finally, although most of the trials reported improvements in medication appropriateness or discrepancies, there has been no study, to date, to evaluate the effects of deprescribing on multiple geriatric syndromes among older patients.

The overarching aim of the Shed-MEDS trial is to determine the effects of a hospital-initiated patient-centered deprescribing intervention among older patients discharged to a post-acute care (PAC) facility, either a skilled nursing facility (SNF) or an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IPR). The primary aim is to determine the effect of patient-centered deprescribing on the change in the total number of medications, which includes the number of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), number of medications associated with geriatric syndromes (MAGS) and medications that contribute to anticholinergic and sedative drug burden, known as the drug burden index (DBI). Secondary aims of the trial include assessing the effect of the deprescribing intervention on medication adherence, functional health status, and the prevalence and severity of geriatric syndromes. The results of this trial will quantify the health outcomes associated with reducing medications for hospitalized older adults with polypharmacy who are discharged to post-acute care facilities.

Methods / design

Protocol reporting

This protocol has been prepared according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) Statement [64, 65]. Trial results will be reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement [66, 67]. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02979353), initially on 12/1/2016, with an update on 09/28/2017 and 10/12/2018. (ACTRN12617001129370). The SPIRIT Checklist is provided as an Additional file 1 and the SPIRIT Table is included as Table 1.

Trial design

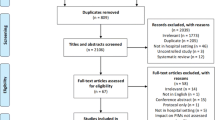

Shed-MEDS is a 5-year randomized, controlled, un-blinded clinical trial at a single academic medical center, funded by the National Institute of Aging (NIA). The intervention is not blinded to enrolled patients; however, group assignment (intervention versus control) and safety outcome assessments are blinded to the outcome assessors not engaged in intervention implementation. The trial design is shown in Fig. 1. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the academic affiliated Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the NIA-appointed Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB). Protocol amendments are first approved by the affiliated IRB then communicated to the NIA and DSMB via the semi-annual DSMB meeting. Other relevant parties are notified through updates to the study information on the clinicaltrials.gov website. All publications from the study will include a summary of all protocol amendments.

Study setting, participants, and eligibility criteria

Patient enrollment for the Shed-MEDS trial began March, 2017 and is scheduled to end October, 2020. Adults, aged 50 and older, hospitalized at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) and referred to post-acute care (PAC) at one of 20 skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) or two inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IPRs) in the Middle Tennessee area are potentially eligible for the study. The age criterion was lowered from 65 to 50 after four months of initial study enrollment because a substantial proportion of hospitalized adults aged 50–64 otherwise met all eligibility criteria. This protocol modification was approved by the IRB. Each of the 22 “partner” PAC facilities (SNF or IPR) provided contact information for designated licensed nursing personnel and a prescribing authority to allow the research team to communicate deprescribing actions for intervention participants and retrieve relevant health information for all study participants during their PAC stay. The written informed consent covers all participating PACs.

Trained research personnel screen patients for additional eligibility criteria on weekdays based on electronic medical record data. Additional study inclusion criteria require the patient to have: five or more medications on their pre-hospital admission medication list (to include all prescription and over-the-counter medications, both scheduled and as needed) and a home residence in one of nine surrounding counties of VUMC to facilitate a home visit during the study follow-up phase 90-days after PAC discharge. Patients are excluded if they are: homeless or incarcerated; do not have a working telephone; reside in long-term care prior to hospitalization; have a limited (< 6 months) life expectancy per medical record documentation (e.g., stage 4 metastatic cancer diagnosis, hospice referral); currently enrolled in a drug trial; or, expected to discharge from the hospital in less than 48 h (due to inadequate time for study assessments). Lastly, patients must be able to speak English and have the capacity to provide self-consent or have a surrogate (i.e., family member or friend) willing to consent on their behalf.

Randomization, allocation, and study phases

Trained research personnel approach eligible patients at the bedside during their hospital stay to obtain informed, written consent (Fig. 1. Phase 1). The consent process also includes a release of healthcare information to allow access to participants’ health records at VUMC or elsewhere for emergency room visits or hospitalizations during the study period.

Following consent, research personnel complete a baseline interview, and participants are randomized to the intervention or control groups (Fig. 1. Phase 2). Participants are randomized in a permuted block fashion, in randomly selected block sizes of two or four. The complete randomization table was created and uploaded to the VUMC Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system, which automatically assigns the randomized allocations to authorized users [68].

Those randomized to intervention receive a second interview with a study Pharmacist (PharmD) or Nurse Practitioner (NP) to review deprescribing recommendations, assess their preferences related to medication changes, and communicate with the treatment team (described below). Participants in both groups are followed through their PAC stay (Fig. 1. Phase 3) during which intervention-initiated deprescribing continues for those in the intervention group. After PAC discharge, research personnel conduct a follow-up telephone interview at 7 (range 4–10) and 60 (range 50–70) days and a home visit at 90 (range 76–104) days (Fig. 1. Phase 4). Additional data are obtained from the hospital medical record, PAC medical record and pharmacy records.

Treatments

Intervention: Patient-centered Deprescribing conceptual framework

The Shed-MEDS deprescribing protocol is based on a conceptual framework that considers patient and disease factors, life expectancy, goals of care, appropriate treatment targets and the duration of treatment required for benefit (Fig. 2) [17]. Medication-specific factors are also incorporated for minimizing inappropriate medication use, such as drug-specific safety profiles, drug-drug and drug-disease interactions [69]. Finally, patient preferences are viewed as a key component that informs final deprescribing actions by identifying medications the patient is willing to deprescribe (e.g., due to lack of efficacy, poor compliance, side effects or cost burden) and potential barriers to deprescribing (e.g., concerns about worsening of symptoms). Specifically, our goal is to identify opportunities for deprescribing wherein clinical evidence aligns with patient preferences. Importantly, deprescribing is defined as stopping medications or reducing the dose or frequency of administration. All medications (prescription and over-the-counter medications including vitamins and herbal supplements) are reviewed for deprescribing potential.

Intervention: Patient-centered Deprescribing steps

Following the baseline patient/surrogate interview and comprehensive medication history for both intervention and control groups, a study PharmD or NP reviews the reconciled medication list for intervention participants only. For each medication on the list, the PharmD or NP conducts a medical record review to determine the medication-indication pairing and deprescribing rationale. The indication (i.e. diagnosis or symptom) for each prescribed medication is specified; if an indication does not exist, “no indication” or “indication unknown” is recorded. Rationales for deprescribing, including no indication for medication, are selected from the list in Table 2. Multiple rationales may be applicable to an individual medication.

For each medication recommended for deprescribing, the deprescribing action is specified as follows: (1) stop prior to hospital discharge without the need for monitoring; (2) stop prior to hospital discharge with symptom/physiologic monitoring; (3) stop at specified time point following hospital discharge; (4) reduce over time with monitoring until medication is stopped; (5) reduce to lower dose without the need for monitoring; and. (6) reduce to lower dose with symptom /physiologic monitoring. The advantage of initiating deprescribing actions during the hospital stay for patients being discharged to a PAC facility (SNF or IPR) is that the SNF/IPR setting affords the opportunity for continued symptom/physiologic monitoring and additional dose reductions or titrations.

Once deprescribing recommendations have been established based on medical record review, the study PharmD/NP conducts a structured interview with the patient/surrogate to elicit their medication preferences. The following is assessed for each medication targeted for deprescribing: medication adherence, side effects, perceived benefit (or harm), cost and level of interest in stopping or reducing the medication. Additionally, patients/surrogates are asked if they are interested in stopping or reducing any medication that has not been recommended by the study PharmD/NP. The goal is to involve the patient/surrogate in the decision-making process related to deprescribing to increase the likelihood of adherence following hospital and PAC discharge.

The agreed-upon list of deprescribing actions is then communicated to the hospital treatment team and/or primary outpatient prescriber(s) via electronic health record messaging (if a VUMC provider) or telephone (if a non-VUMC provider). The goal of these conversations is to obtain provider feedback about the proposed medication changes and facilitate medication updates in the patient’s medical record(s). The study PharmD/NP coordinates with the hospital treatment team to incorporate all final deprescribing actions into the transfer orders at the time of hospital discharge to the PAC facility.

To ensure understanding, the study PharmD/NP contacts a designated PAC provider via telephone within 24 h of transfer to review the orders, with particular attention to medications that have a dose reduction, titration and/or the need for symptom/physiologic monitoring. Additionally, medications that were stopped prior to hospital discharge and the deprescribing rationale are reviewed during this call. The study PharmD/NP-to-PAC nurse phone call is also used to inform the PAC facility of amended orders if the patient discharges to the PAC facility before deprescribing actions can be incorporated into the initial transfer orders. Additionally, a copy of the amended orders is sent to the PAC facility.

Following the initial PAC hand-off, the study PharmD/NP initiates a weekly conversation via telephone with a designated PAC provider to review intervention participants’ medication administration record and evidence of symptom worsening or drug withdrawal. Reasons for modifying the transfer medication list during the PAC stay are discussed and intervened upon, as necessary. The study PharmD/NP also may continue to communicate with the original prescriber (primary care provider or specialist) during the patient’s PAC stay to confirm their agreement with continued medication changes. At the time of discharge from the PAC facility, a final medication list is reconciled by the study team for intervention participants. This list is provided to the patient’s primary outpatient prescriber(s), along with suggestions for continued medication management and deprescribing, when applicable, along with the rationale for these changes.

Control group: Usual care

Patients randomized to usual care undergo medication review performed by the study team at hospital admission, hospital discharge, and PAC discharge. The goal of this medication review process is to obtain an accurate medication list for study records and assessment without making recommendations about deprescribing. We chose a usual care comparator, as there are no current established gold-standard, effective, deprescribing interventions. All medication decisions for the control group, prescribing or deprescribing, are at the discretion of the treating teams in the hospital, PAC setting, and post-discharge providers. The study team alerts provider(s) to substantial medication discrepancies that pose imminent safety hazards discovered during the medication history-taking process.

Interview measures and data collection

Table 1 shows all study measures and the data collection time points. To promote participant retention and complete follow-up, participants are paid $10 after baseline assessments are complete and up to an additional $40 for completing follow-up time points (7, 60 and 90 days). Participants may be discontinued from the study for the following reasons, in which case there are no data collected past the date of discontinuation: discharge from the hospital to a non-partner PAC facility or home, consent withdrawal, transition to hospice care or death. Each study measure listed in Table 1 is briefly described below.

Demographic, comorbidity, and attitudes toward Deprescribing

Research personnel use a standardized form to abstract information from participants’ electronic medical record upon enrollment to include demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity), contact information (home address/telephone), insurance status, education level, outpatient providers and pharmacies. We also abstract the participant’s location immediately prior to hospital admission, hospital admission and discharge dates (length of stay), admission diagnoses, hospital service, pre-admission and in-hospital medication lists. These data are reviewed and verified with the patient and/or surrogate during a baseline interview at the hospital bedside (Fig. 1. Phase 1).

Medical diagnoses are used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Score [70] for each patient, which ranges from 0 to 31, with a higher score indicating more comorbid illness. There is an additional one-unit increase in the weighted score for every decade starting from age 50. Data sources for comorbidities are the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria from the last 12 months [71]. Medical record data also is used to calculate the Walter Index, which is a prognostic tool to predict one-year mortality among older adults after hospital discharge [72]. A higher score is indicative of a greater likelihood of mortality within one year (e.g., scores > 6 = 64% estimated mortality rate). Lastly, medical diagnoses and history are used to calculate the older patient’s risk for an adverse drug event via the GerontoNet Adverse Drug Event risk assessment [20].

We administer the Patients’ Attitudes Toward Deprescribing (PATD) tool, which consists of 15 items. Ten items are statements with a 5-point Likert scale response option from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Examples include: “I feel that I am taking a large number of medicines” and “I believe that all my medicines are necessary”. The remaining five questions are related to the patient’s perception of their total number of medications (e.g., “How many different tablets/capsules per day would you consider to be a lot?”), history and comfort level with stopping one or more medicines [73].

Primary outcome measure: Medications

Multiple data sources are used to compile a comprehensive list of all medications to include the hospital medical record, patient/surrogate interview, pharmacy records (refill history) and the PAC (SNF or IPR) medical record. Medications at study enrollment (Fig. 1. Phase 1. Baseline) include any medication that has the potential to be continued at the time of hospital discharge. This includes (a) pre-hospital medications, (b) active in-hospital medications not on the pre-hospital medication list; and, (c) medications identified via patient/surrogate interview and/or pharmacy records, including mail-order pharmacies, for the three months prior to hospitalization. All prescribed (scheduled and as needed) and over-the-counter medications (including vitamins and herbal supplements) administered by any route other than topical are included in the patient’s comprehensive medication list.

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) are defined by previously published lists including the recently updated Beers criteria [12], the STOPP criteria [13, 14], and the Rationalization of home medication by an Adjusted STOPP in older Patients (RASP) list [15], for which there is a large degree of overlap. The total number of PIMs is the sum of unique medications found on any of these explicit lists. The total number of medications associated with geriatric syndromes is based on a detailed list of specific medications delineated in a prior study [45]. These medications have an evidence-base, expert consensus or care practice guideline, and/or > 5% side effect incidence per the Lexicomp Online® database and/or Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved package inserts indicating an association between the medication and one or more geriatric syndromes.

Based on the comprehensive list of all medications, a Drug Burden Index (DBI) score is calculated per participant for anticholinergic (DBIAC) and sedative medications (DBIS) separately. Anticholinergic and sedative medications have been strongly linked to functional impairment [25, 26, 34, 74], falls [75,76,77], and delirium [78,79,80]. The DBI is the sum of each individual anticholinergic/sedative medication’s prescribed daily dose divided by the sum of the minimum effective dose (as estimated by the FDA minimum recommended dose) and the patient’s daily dose.

Secondary outcome measures: Geriatric syndromes

Table 1 lists eight geriatric syndromes, each of which is assessed by trained research personnel via a standardized instrument and patient interview during their hospital stay (Fig. 1. Phase 1) and again following PAC discharge (Fig. 1. Phase 4) via telephone at 7 days and in-person during a home visit at 90 days. Additionally, a copy of the discharge Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessment or Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI), which is required for all SNF or IPR patients respectively, is retrieved from the PAC medical record for each participant as a measure of these syndromes during the PAC stay.

The Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM) is a screening tool for delirium that has been validated among hospitalized, older patients [81, 82]. If the patient screens positive for delirium, no other patient interviews are conducted at that time. Research personnel continue to re-assess delirium daily during hospitalization; and, when the patient screens negative for delirium via the bCAM, the remaining assessments are administered to the patient. If delirium continues throughout the hospital stay or the patient is otherwise unable or unwilling to complete the assessments, the surrogate is approached for a sub-set of the geriatric syndrome assessments (i.e., incontinence, nutrition and fall history). The bCAM is not repeated by research personnel at 7-day follow-up because it has limited validity when administered via the telephone [83]; thus, it is repeated only at 90-day follow-up during the in-person home visit (Table 1). Additionally, PAC personnel use the CAM (i.e., the Confusion Assessment Method, [CAM]), which is a modified version of the bCAM, to assess delirium during the PAC stay via the MDS assessment.

Cognitive impairment is assessed with the Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS), which has a total score range from 0 to 15 (0–7: severe impairment; 8–12: moderate impairment; 13–15: cognitively intact) [84, 85]. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a validated tool to assess depression symptoms and severity [86]. Each item is scored from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”) to yield a total score range from 0 (no depressive symptoms) to 27 (severe depression). Both the BIMS and the PHQ-9 are also part of the MDS assessment.

The International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire - Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) consists of four items that assess the symptoms, frequency and impact of urinary incontinence on quality of life. [87] This tool has well established reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .95) and validity, including sensitivity to treatment. The MDS has one item for urinary incontinence frequency scored 0 (‘always continent’) to 3 ‘always incontinent’).

Nutritional risk is assessed with the 10-item “Determine Your Nutritional Health checklist”, which yields a total nutritional risk score of 0–2 (“low”), 3–5 (“moderate”), or > 6 (“high”). The DETERMINE checklist has been validated in a longitudinal study of community-dwelling older adults [88]. If the participant endorses a weight change of 10 pounds or more on the DETERMINE item, a structured follow-up question is posed to clarify whether the weight change reflects a gain versus a loss. The MDS has one item for unintentional weight loss, defined as 5% or more in 30 days or 10% or more in 180 days.

Pain is assessed with the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) Short-Form, which is a validated instrument for assessing pain location, severity and interference with daily activities among older adults [89, 90]. Pain severity is based on four questions wherein participants use a 0 (no pain) to 10 (worse pain imaginable) scale to rate their pain in the last 24-h under four conditions: at its worst, at its least, on average, and now. Pain is assessed in the PAC setting via the MDS, which includes items related to pain frequency, effect on function and intensity.

Pressure ulcers (number and stages 1–4 or unstageable) are abstracted from the hospital and PAC medical record and confirmed via patient/surrogate interview at each time point. Fall history in the month prior to hospitalization (frequency = 0, 1 or 2 or more fall events) is assessed via patient/surrogate interview. Falls during the PAC stay are abstracted from the PAC medical record (number of falls since PAC admission) and confirmed via patient/surrogate interview. Additionally, patients are interviewed about falls after PAC discharge during the follow-up phase.

Secondary outcomes: Medication adherence and functional health status

The Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) consists of 12 items to assess overall medication adherence, with a total score range of 12 to 48. A lower score is indicative of better medication adherence [91]. Example questions include: “How often do you forget to take your medicines?”, “How often do you miss taking your medicines when you feel better?”, and “How often do you put off refilling your medicines because they cost too much money?” Response options are on a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from “none of the time” to “all of the time”. The Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13) is a functional measure of health status that assesses a patient’s cognitive, physical and self-care activities and includes an item for self-rated health status. Scores range from 1 to 10, with a lower score indicative of better health [92, 93].

Safety measures: Healthcare utilization and adverse drug events

Unplanned healthcare utilization (intensive care unit transfers, emergency department visit and/or hospitalizations) is monitored throughout all study phases for each participant. Unplanned events are assessed by physician co-investigators blind to group assignment using a structured review protocol of all relevant medical records from both within and outside of VUMC. Physician reviewers determine whether the unplanned healthcare utilization is related to an adverse drug event (ADE) and medication withdrawal (i.e., adverse drug withdrawal event, [ADWE]) using the 10-question Drug Withdrawal Probability Scale [94], a scale based on the Naranjo algorithm [95], which is a validated scoring system to assess causality of adverse drug events. Deaths and transitions to hospice are also monitored for all participants.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, participants are not blinded to the intervention. In addition, the PharmD and NP delivering the patient-centered deprescribing intervention cannot be blinded. However, the investigators and the statistician performing data analyses are blinded to group assignment. Additionally, the physician co-investigators who review patients’ medical records to assess ADEs and ADWEs (safety measures) are blinded to group assignment.

Statistical methods

The effect of the intervention on the total number of medications, PIMs, and medications associated with geriatric syndromes (MAGS) at hospital discharge, PAC discharge, and 90-days following PAC discharge will be quantified using mixed effects Poisson regression, allowing for over dispersion (more or less variability than is expected under the Poisson regression model), and adjusting for measurement time point (as a categorical covariate), the total number of medications at participant enrollment and the interaction of intervention and time point. The within-subject correlation among repeated measurements will be modeled using a random intercept term, indexed by subject. The overall statistical significance of the intervention effect will be evaluated using a Wald-type multiple degree-of-freedom test against the null hypothesis of no effect at any time point after randomization. P-values less than 0.05 will be considered statistically significant. The intervention effect at each time point will be summarized using a Wald-type 95% confidence interval. Model fit will be assessed by examining the associated Pearson residuals and using other graphical methods. Alternative regression techniques may be used in the case of poor fit, for example, cumulative logit regression methods.

The effect of intervention on the anticholinergic and sedative drug burden (DBI) scores at hospital discharge, PAC discharge and 90-days following PAC discharge will be assessed in a similar fashion as described above, using linear mixed effects regression rather than Poisson regression. Due to the constrained nature of the score values (0–1 for anticholinergic and sedative drug burden scores), an alternative method may be required, such a ‘beta’ regression, which is suitable when such scores frequently occur at a boundary (0 or 1).

The prevalence and severity of geriatric syndromes will be analyzed at each time point following PAC discharge. The effects of intervention on the prevalence of each type of geriatric syndrome will be assessed using mixed-effects logistic regression, in a manner similar to that described above. The severity of each geriatric syndrome is measured on an ordinal scale, where the absence of a geriatric syndrome will be treated as the lowest category of severity. Thus, severity will be similarly analyzed using mixed-effects proportional odds logistic regression.

Patient medication adherence will be measured using the ARMS total score, which is based on an ordinal scale. Functional health status is measured using the VES-13 total score, which is also an ordinal outcome. The effects of intervention on these outcomes at 7 and 90-days following PAC discharge will be quantified using mixed-effects logistic regression or proportional odds logistic regression in a manner that is analogous to that described above.

Missing data and intent-to-treat

We will examine the incidence of missing data by group. If imbalances are found, we will implement a series of sensitivity analyses, using a chained-equations multiple imputation method, to assess the degree of bias that might be induced by missing data. Records for all randomized patients will be included in analyses.

Preservation of type-I error rate

Overall effectiveness of the intervention will be assessed using a multiple degree-of-freedom test against the null hypothesis of no intervention effect on the primary outcome (change in the total number of medications) at any time point after randomization. A p-value less than 0.05 will be considered statistically significant. Thus, the type-I error rate for the assessment of overall effectiveness is fixed at 5%. All other outcomes will be treated as secondary or exploratory endpoints, or as components of the primary outcome (e.g., PIMS, MAGS, DBI). Statistical tests and confidence intervals will be used to summarize the effect of intervention on secondary/exploratory outcomes but will not be used to assess overall effectiveness. We will not make adjustments to control the familywise type-I error potentially associated with tests of secondary / exploratory outcomes [96].

Power and sample size

The overall effectiveness of the intervention will be evaluated based on the primary outcome measure, which is total medication count. Based on our current enrollment rate, we estimate that approximately 144 patients per year will enroll in the study, or 576 across all four years of enrollment. Among those, we estimate that 27.5% will either die or otherwise be lost from the study prior to the 90-day post PAC discharge follow up period. Thus, across all four years of enrollment, an estimated 420 patients will contribute measurements at 90 days. Although 567 is the expected total enrollment, we conservatively use 420 to estimate the statistical power associated with the assessment of overall effectiveness (i.e., overall completion rate) rather than enrollment rate, to account for estimated attrition across all study phases.

Preliminary data is available for the effect of deprescribing on the reduction in the counts of total medications [97]. Our pilot intervention (N = 40) was associated with roughly a 50% reduction in the count of total medications from enrollment to hospital discharge, whereas a roughly 25% reduction was observed in the control group receiving routine hospital care [97]. Using these preliminary data and mixed-effects Poisson regression methods, we implemented a simulation-based power analysis wherein we assumed that this effect would be attenuated by 20% at SNF discharge, and again by 20% at the 90-day follow up. Using a sample size of 420, there is greater than 95% power to detect a 50% versus 25% reduction in total medications. There is approximately 90% power to detect a 30% versus 25% reduction in total medications, and 80% power to detect a 27.5% versus 25% reduction in total medications. Thus, the target sample size provides some protection against effects that are substantially smaller than that observed in our preliminary data.

Data integrity and privacy

All study data are collected by trained research personnel during each study phase. Participants each receive a unique study identifier. All data are collected via hard copy forms and managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform [67], Microsoft Excel and SPSS (Version 25). REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data entry, validation and management. All hard copy data collection forms are kept in locked, secure file cabinets and other electronic data is stored on a secure shared computer drive, which is only accessible by study personnel. Study coordinators conduct weekly quality assurance reviews to ensure data accuracy when data is translated from hard copy forms to electronic databases.

Access to data and dissemination policy

Trial investigators will have full access to the final trial dataset. There are no contractual agreements that limit such access to investigators. Investigators plan on publishing results for all pre-specified primary and secondary outcomes in the peer-reviewed literature. Publications will include publication of the full study protocol and access to statistical code, upon request for review.

Data and safety monitoring board (DSMB)

This clinical trial has an DSMB. The DSMB is independent, and acts in an advisory capacity to the NIA Director to monitor participant safety, data quality and evaluate the progress of the study. The DSMB consists of five members, and 3 members constitute a quorum. Members were selected by an NIA Program Official in consultation with the investigators, and the NIA Director approved the composition of the DSMB and its membership. The DSMB includes experts in the fields of relevant clinical expertise in geriatrics, clinical trial methodology, and biostatistics. Monthly safety reports are submitted to NIA and semi-annual DSMB meetings are held to review safety data. The NIA Program Official or designee attend each meeting. An emergency meeting of the DSMB may be called at any time by the Chair or by the NIA should participant safety questions or other unanticipated problems arise. In the case of a serious adverse event that results in death, the Principal Investigators are required to inform the NIA within 48 h of notification.

Discussion

Polypharmacy is prevalent among hospitalized older patients; however, the health outcomes associated with deprescribing are largely unknown, particularly as these relate to geriatric syndromes. The VUMC Shed-MEDS study is the first randomized controlled trial to evaluate a comprehensive deprescribing intervention for hospitalized, older patients discharged to a PAC facility (SNF or IPR). It is also one of the few deprescribing studies to incorporate patients’ preferences into the decision-making process in a structured way. The results of this trial will quantify the number and type of medication changes that can be initiated and maintained across the continuum of care from hospital to PAC facility to home. Additionally, this trial will examine the impact of medication reductions on adherence, geriatric syndromes and functional health status.

One limitation of the study is the lack of blinding of the patient to the intervention, which could potentially bias the self-reported outcome measures (secondary aim). However, there are measures in place to reduce this bias, including the blinding of outcome assessors and the analytic team to group allocation and the use of standardized, reliable assessment tools for each measure. This study is currently the largest known acute care deprescribing trial, to date, and the first to follow patients into the PAC setting, generating substantial new knowledge related to the efficacy and safety of acute care-initiated patient-centered deprescribing efforts for older patients with polypharmacy.

Trial status

Enrollment to date

Trial recruitment began March 1st, 2017. The trial protocol has undergone revisions and is currently at version two. We anticipate that recruitment will be completed October 31, 2020.

Abbreviations

- ADE:

-

Adverse Drug Event

- ADWE:

-

Adverse Drug Withdrawal Event

- ARMS:

-

Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale

- bCAM:

-

Brief Confusion Assessment Method

- BIMS:

-

Brief Interview for Mental Status

- BPI:

-

Brief Pain Inventory

- CAM:

-

Confusion Assessment Method

- DBI:

-

Drug Burden Index

- DETERMINE:

-

Determine Your Nutritional Health Checklist

- DSMB:

-

Data Safety and Monitoring Board

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- ICIQ-UI SF:

-

International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire - Urinary Incontinence Short Form

- IPR:

-

Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility

- MDS:

-

Minimum Data Set

- NIA:

-

National Institute on Aging

- PAC:

-

Post-acute Care

- PATD:

-

Patients’ Attitudes Toward Deprescribing

- PHQ:

-

The Patient Health Questionnaire

- PIMS:

-

Potentially inappropriate medications

- RASP:

-

Rationalization of home medication by an Adjusted STOPP in older Patients

- SNF:

-

Skilled Nursing Facility

- STOPP:

-

Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions

- VES:

-

Vulnerable Elders Survey

- VUMC:

-

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

References

Best O, Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ. Investigating polypharmacy and drug burden index in hospitalised older people. Intern Med J. 2013;43:912–8.

Steinman MA, Seth Landefeld C, Rosenthal GE, Berthenthal D, Sen S, Kaboli PJ. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1516–23.

Aparasu RR, Mort JR, Brandt H. Polypharmacy trends in office visits by the elderly in the United States, 1990 and 2000. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2005;1:446–59.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:989–95.

Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, Lindblad CI, Pieper CF, Ruby CM, et al. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1518–23.

Gamble J-M, Hall JJ, Marrie TJ, Sadowski CA, Majumdar SR, Eurich DT. Medication transitions and polypharmacy in older adults following acute care. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:189–96.

Cannon KT, Choi MM, Zuniga MA. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly patients receiving home health care: a retrospective data analysis. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:134–43.

Hanlon JT, Artz MB, Pieper CF, Lindblad CI, Sloane RJ, Ruby CM, et al. Inappropriate medication use among frail elderly inpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:9–14.

Schmader K, Hanlon J, Weinberger M, Landsman PB, Samsa GP, Lewis I, et al. Appropriateness of medication prescribing in ambulatory elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1241–7.

Hines LE, Murphy JE. Potentially harmful drug–drug interactions in the elderly: a review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:364–77.

Dechanont S, Maphanta S, Butthum B, Kongkaew C. Hospital admissions/visits associated with drug–drug interactions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:489–97.

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel, Fick DM, Semla TP, Beizer J, Brandt N, Dombrowski R, et al. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–46.

Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. STOPP (screening tool of older persons’ potentially inappropriate prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with beers’ criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37:673–9.

Gallagher P, Baeyens J-P, Topinkova E, Madlova P, Cherubini A, Gasperini B, et al. Inter-rater reliability of STOPP (screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions) and START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment) criteria amongst physicians in six European countries. Age Ageing. 2009;38:603–6.

Van der Linden L, Decoutere L, Flamaing J, Spriet I, Willems L, Milisen K, et al. Development and validation of the RASP list (rationalization of home medication by an adjusted STOPP list in older patients): a novel tool in the management of geriatric polypharmacy. Eur Geriatric Med. 2014;5:175–80.

Geijteman ECT, van Gelder T, van Zuylen L. Sense and nonsense of treatment of comorbid diseases in terminally ill patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:346.

Holmes HM, Hayley DC, Alexander GC, Sachs GA. Reconsidering medication appropriateness for patients late in life. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:605–9.

Col N. The role of medication noncompliance and adverse drug reactions in hospitalizations of the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:841.

Steinman MA, Lund BC, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Kaboli PJ. Geriatric Conditions, Medication Use, and Risk of Adverse Drug Events in a Predominantly Male, Older Veteran Population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):615–21.

Onder G, Petrovic M, Tangiisuran B, et al. Development and validation of a score to assess risk of adverse drug reactions among in-hospital patients 65 years or older: the gerontonet adr risk score. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1142–8.

Flaherty JH, Perry HM, Lynchard GS, Morley JE. Polypharmacy and hospitalization among older home care patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M554–9.

Morandi A, Bellelli G, Vasilevskis EE, Turco R, Guerini F, Torpilliesi T, et al. Predictors of rehospitalization among elderly patients admitted to a rehabilitation hospital: the role of polypharmacy, functional status, and length of stay. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.013.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Hartikainen S, Tolppanen A-M, Taipale H, Koponen M, et al. Impact of high risk drug use on hospitalization and mortality in older people with and without Alzheimer’s disease: a National Population Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83224.

Sganga F, Landi F, Ruggiero C, Corsonello A, Vetrano DL, Lattanzio F, et al. Polypharmacy and health outcomes among older adults discharged from hospital: results from the CRIME study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:141–6.

Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:781–7.

Gnjidic D, Cumming RG, Le Couteur DG, Handelsman DJ, Naganathan V, Abernethy DR, et al. Drug burden index and physical function in older Australian men. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:97–105.

Oyarzun-Gonzalez XA, Taylor KC, Myers SR, Muldoon SB, Baumgartner RN. Cognitive decline and polypharmacy in an elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:397–9.

Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, Hanlon JT, Hubbard R, Walker R, et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:401.

Cao Y-J, Mager D, Simonsick E, Hilmer S, Ling S, Windham B, et al. Physical and cognitive performance and burden of anticholinergics, sedatives, and ACE inhibitors in older women. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:422–9.

Hein C, Forgues A, Piau A, Sommet A, Vellas B, Nourhashémi F. Impact of polypharmacy on occurrence of delirium in elderly emergency patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:850.e11–5.

Landi F, Dell’Aquila G, Collamati A, Martone AM, Zuliani G, Gasperini B, et al. Anticholinergic drug use and negative outcomes among the frail elderly population living in a nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:825–9.

Lu W-H, Wen Y-W, Chen L-K, Hsiao F-Y. Effect of polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medications and anticholinergic burden on clinical outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2015;187(4):E130–7.

Fraser L-A, Liu K, Naylor KL, Hwang YJ, Dixon SN, Shariff SZ, et al. Falls and fractures with atypical antipsychotic medication use: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:450–2.

Bennett A, Gnjidic D, Gillett M, Carroll P, Matthews S, Johnell K, et al. Prevalence and impact of fall-risk-increasing drugs, polypharmacy, and drug–drug interactions in robust versus frail hospitalised falls patients: a prospective cohort study. Drugs Aging. 2014;31:225–32.

Huang ES, Karter AJ, Danielson KK, Warton EM, Ahmed AT. The association between the number of prescription medications and incident falls in a multi-ethnic population of adult Type-2 diabetes patients: the diabetes and aging study. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:141–6.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Le Couteur DG. Optimal cutoff of polypharmacy and outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:465–6.

Moulis F, Moulis G, Balardy L, Gérard S, Sourdet S, Rougé-Bugat M-E, et al. Searching for a polypharmacy threshold associated with frailty. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:259–61.

Lau DT, Mercaldo ND, Shega JW, Rademaker A, Weintraub S. Functional decline associated with polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in community-dwelling older adults with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26:606–15.

Kashyap M, Tu LM, Tannenbaum C. Prevalence of commonly prescribed medications potentially contributing to urinary symptoms in a cohort of older patients seeking care for incontinence. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:57.

Hall SA, Yang M, Gates MA, Steers WD, Tennstedt SL, McKinlay JB. Associations of commonly used medications with urinary incontinence in a community based sample. J Urol. 2012;188:183–9.

Gormley EA, Griffiths DJ, McCRACKEN PN, Harrison GM. Polypharmacy and its effect on urinary incontinence in a geriatric population. Br J Urol. 1993;71:265–9.

Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:514–22.

Jensen GL, Friedmann JM, Coleman CD, Smiciklas-Wright H. Screening for hospitalization and nutritional risks among community-dwelling older persons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:201–5.

Heuberger DRA, Caudell K. Polypharmacy and nutritional status in older adults. Drugs Aging. 2012;28:315–23.

Saraf AA, Petersen AW, Simmons SF, Schnelle JF, Bell SP, Kripalani S, et al. Medications associated with geriatric syndromes and their prevalence in older hospitalized adults discharged to skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(10):694–700.

Bell SP, Vasilevskis EE, Saraf AA, Jacobsen JML, Kripalani S, Mixon AS, et al. Geriatric syndromes in hospitalized older adults discharged to skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:715–22.

Kane RL, Shamliyan T, Talley K, Pacala J. The association between geriatric syndromes and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:896–904.

Wang S-Y, Shamliyan TA, Talley KMC, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Not just specific diseases: systematic review of the association of geriatric syndromes with hospitalization or nursing home admission. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57:16–26.

Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post–acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:295.

Kramer A, Fish R, Min S. Community discharge and Rehospitalization outcome measures. Washington DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2013. http://ww1.prweb.com/prfiles/2014/03/04/11640554/Apr2013_Community_Discharge_CONTRACTOR_report.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2018

Patterson SM, Hughes C, Kerse N, Cardwell CR, Bradley MC. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD008165.

Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, Valluri S, Briesacher BA. Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:285–307.

Dills H, Shah K, Messinger-Rapport B, Bradford K, Syed Q. Deprescribing medications for chronic diseases Management in Primary Care Settings: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(11):923–935.e2.

Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, Hilmer SN. Impact of Deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:303–19.

Niehoff KM, Rajeevan N, Charpentier PA, Miller PL, Goldstein MK, Fried TR. Development of the tool to reduce inappropriate medications (TRIM): a clinical decision support system to improve medication prescribing for older adults. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:694–701.

Poquet I, Tornero C. Deprescription at hospital discharge: outcomes of a deprescription promoting campaign. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;42:e22–3.

Marvin V, Ward E, Poots AJ, Heard K, Rajagopalan A, Jubraj B. Deprescribing medicines in the acute setting to reduce the risk of falls. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract. 2017;24:10–5.

Urfer M, Elzi L, Dell-Kuster S, Bassetti S. Intervention to improve appropriate prescribing and reduce polypharmacy in elderly patients admitted to an internal medicine unit. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166359.

McKean M, Pillans P, Scott IA. A medication review and deprescribing method for hospitalised older patients receiving multiple medications. Intern Med J. 2016;46:35–42.

Reeve E, Wolff JL, Skehan M, Bayliss EA, Hilmer SN, Boyd CM. Assessment of attitudes toward deprescribing in older Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1673–80.

Todd A, Jansen J, Colvin J, McLachlan AJ. The deprescribing rainbow: a conceptual framework highlighting the importance of patient context when stopping medication in older people. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:295.

Weir K, Nickel B, Naganathan V, Bonner C, McCaffery K, Carter SM, et al. Decision-making preferences and Deprescribing: perspectives of older adults and companions about their medicines. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73:e98–107.

Holmes HM, Todd A. The role of patient preferences in deprescribing. Clin Geriatr Med. 2017;33:165–75.

Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586.

Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche PC, Krleža-Jerić K, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158 https://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/1556168/spirit-2013-statement-defining-standard-protocol-items-clinical-trials. Accessed 12 Mar 2019.

Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, for the CONSORT NPT Group. CONSORT Statement for Randomized Trials of Nonpharmacologic Treatments: A 2017 Update and a CONSORT Extension for Nonpharmacologic Trial Abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0046.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8:18.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, Mitchell CA. Minimizing Inappropriate Medications in Older Populations: A 10-step Conceptual Framework. Am J Med. 2012;125:529–537.e4.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, Mackenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Li B, Evans D, Faris P, Dean S, Quan H. Risk adjustment performance of Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidities in ICD-9 and ICD-10 administrative databases. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:12.

Walter LC, Brand RJ, Counsell SR, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS, Fortinsky RH, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 1-year mortality in older adults after hospitalization. JAMA. 2001;285:2987–94.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Development and validation of the patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (PATD) questionnaire. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;35:51–6.

Gnjidic D, Couteur DGL, Abernethy DR, Hilmer SN. Drug burden index and beers criteria: impact on functional outcomes in older people living in self-care retirement villages. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:258–65.

Nishtala PS, Narayan SW, Wang T, Hilmer SN. Associations of drug burden index with falls, general practitioner visits, and mortality in older people. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:753–8.

Dauphinot V, Faure R, Omrani S, Goutelle S, Bourguignon L, Krolak-Salmon P, et al. Exposure to anticholinergic and sedative drugs, risk of falls, and mortality: an elderly inpatient, Multicenter Cohort. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:565–70.

Wilson NM, Hilmer SN, March LM, Cameron ID, Lord SR, Seibel MJ, et al. Associations between drug burden index and falls in older people in residential aged care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:875–80.

Rothberg MB, Herzig SJ, Pekow PS, Avrunin J, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Association between sedating medications and delirium in older inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:923–30.

Campbell N, Perkins A, Hui S, Khan B, Boustani M. Association between prescribing of anticholinergic medications and incident delirium: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(Suppl 2):S277–81.

Han L, McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, Primeau F, Elie M. Use of medications with anticholinergic effect predicts clinical severity of delirium symptoms in older medical inpatients. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1099–105.

Han JH, Wilson A, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani A, Schnelle JF, Dittus RS, et al. Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:457–65.

Han JH, Wilson A, Graves AJ, Shintani A, Schnelle JF, Dittus RS, et al. Validation of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:180–7.

Marcantonio ER, Michaels M, Resnick NM. Diagnosing delirium by telephone. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:621–3.

Chodosh J, Edelen MO, Buchanan JL, Yosef JA, Ouslander JG, Berlowitz DR, et al. Nursing home assessment of cognitive impairment: development and testing of a brief instrument of mental status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2069–75.

Saliba D, Buchanan J, Edelen MO, Streim J, Ouslander J, Berlowitz D, et al. MDS 3.0: Brief Interview for Mental Status. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:611–7.

Saliba D, DiFilippo S, Edelen MO, Kroenke K, Buchanan J, Streim J. Testing the PHQ-9 Interview and Observational Versions (PHQ-9 OV) for MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:618–25.

Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:322–30.

Buys DR, Roth DL, Ritchie CS, Sawyer P, Allman RM, Funkhouser EM, et al. Nutritional risk and body mass index predict hospitalization, nursing home admissions, and mortality in community-dwelling older adults: results from the UAB study of aging with 8.5 years of follow-up. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1146–53.

Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein JD, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. J Pain. 2004;20:309–18.

Eggermont LHP, Leveille SG, Shi L, Kiely DK, Shmerling RH, Jones RN, et al. Pain characteristics associated with the onset of disability in older adults: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly Boston study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1007–16.

Kripalani S, Risser J, Gatti ME, Jacobson TA. Development and evaluation of the adherence to refills and medications scale (ARMS) among low-literacy patients with chronic disease. Value Health. 2009;12:118–23.

Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein L. The vulnerable elders survey (VES-13): a tool for identifying vulnerable elders in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1691–9.

Mohile SG, Bylow K, Dale W, Dignam J, Martin K, Petrylak DP, et al. A pilot study of the vulnerable elders survey-13 compared with the comprehensive geriatric assessment for identifying disability in older patients with prostate cancer who receive androgen ablation. Cancer. 2007;109:802–10.

Graves T, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, et al. Adverse events after discontinuing medications in elderly outpatients. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2205–10.

Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45.

Cook RJ, Farewell VT. Multiplicity Considerations in the Design and Analysis of Clinical Trials. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc. 1996;159:93–110.

Petersen AW, Shah AS, Simmons SF, Shotwell MS, Jacobsen JML, Myers AP, et al. Shed-MEDS: pilot of a patient-centered deprescribing framework reduces medications in hospitalized older adults being transferred to inpatient postacute care. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:523–33.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to the members of the Shed-Meds team, which includes the following personnel beyond those listed as coauthors: Carole Bartoo, GNP; Jennifer Kim, GNP; Kanah Lewallen, GNP; Whitney Narramore, PharmD; Robin Parker, PharmD; Susan Lincoln, BS; Joanna Gupta, M.Ed.

Funding

This research study was funded by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health award R01AG053264 which as awarded to the two co-principal investigators Drs. Vasilevskis and Simmons. The use of institutional data management system RedCap is supported by CTSA award UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The protocol design is solely the responsibility of the authors. The funders of this research had they have no direct role in the design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of data.

This was the first study related manuscript submitted for publication. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies or the National Center for Advancing Translation Science.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed to refinement of the protocol, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript. EV, AS, EH, AM, SPB, SK, JS, and SS were involved in the intervention design. EV and SS obtained funding for the study. EV, AS, EH, AM, SPB, SK, JS, and SS initiated the study design. EV, AS, EH, JS, and SS drafted the protocol.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was granted by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board IRB#161571. Written Informed consent is obtained from each patient (or their respective surrogate) in the Shed-MEDS trial.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

SPIRIT Checklist (DOCX 48 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Vasilevskis, E.E., Shah, A.S., Hollingsworth, E.K. et al. A patient-centered deprescribing intervention for hospitalized older patients with polypharmacy: rationale and design of the Shed-MEDS randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 165 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3995-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3995-3