Abstract

Background

The Kenyan Ministry of Health- Department of Standards and Regulations sought to operationalize the Kenya Quality Assurance Model for Health. To this end an integrated quality management system based on validated indicators derived from the Kenya Quality Model for Health (KQMH) was developed and adapted to the area of Reproductive and Maternal and Neonatal Health, implemented and analysed.

Methods

An integrated quality management (QM) approach was developed based on European Practice Assessment (EPA) modified to the Kenyan context. It relies on a multi-perspective, multifaceted and repeated indicator based assessment, covering the 6 World Health Organization (WHO) building blocks. The adaptation process made use of a ten step modified RAND/UCLA appropriateness Method. To measure the 303 structure, process, outcome indicators five data collection tools were developed: surveys for patients and staff, a self-assessment, facilitator assessment, a manager interview guide. The assessment process was supported by a specially developed software (VISOTOOL®) that allows detailed feedback to facility staff, benchmarking and facilitates improvement plans. A longitudinal study design was used with 10 facilities (6 hospitals; 4 Health centers) selected out of 36 applications. Data was summarized using means and standard deviations (SDs). Categorical data was presented as frequency counts and percentages.

Results

A baseline assessment (T1) was carried out, a reassessment (T2) after 1.5 years. Results from the first and second assessment after a relatively short period of 1.5 years of improvement activities are striking, in particular in the domain ‘Quality and Safety’ (20.02%; p < 0.0001) with the dimensions: use of clinical guidelines (34,18%; p < 0.0336); Infection control (23,61%; p < 0.0001). Marked improvements were found in the domains ‘Clinical Care’ (10.08%; p = 0.0108), ‘Management’ (13.10%: p < 0.0001), ‘Interface In/out-patients’ (13.87%; p = 0.0246), and in total (14.64%; p < 0.0001). Exemplarily drilling down the domain ‘clinical care’ significant improvements were observed in the dimensions ‘Antenatal care’ (26.84%; p = 0.0059) and ‘Survivors of gender-based violence’ (11.20%; p = 0.0092). The least marked changes or even a -not significant- decline of some was found in the dimensions ‘delivery’ and ‘postnatal care’.

Conclusions

This comprehensive quality improvement approach breathes life into the process of collecting data for indicators and creates ownership among users and providers of health services. It offers a reflection on the relevance of evidence-based quality improvement for health system strengthening and has the potential to lay a solid ground for further certification and accreditation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

In the drive to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) the importance of quality of care has been accentuated by the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. Challenges in service delivery, efficiency and resource utilization in the health sector remain regardless of recent progress.

In recent years, quality of health care has ascended high on the international health agenda especially in the context of Health System Strengthening (HSS) and UHC. Mortality and morbidity rates haven’t declined accordingly [1] although health care utilization rates increased in some low and middle income countries (LMIC). [2, 3] This discrepancy might be expounded by the low quality of care provided in both the public and private sector [4].

In Kenya, but also on a global scale, large and often unexplained differences in quality assessments can be observed between hospitals, facilities and providers. This raises the question of whether these are true differences or the result of weak measurement methods or quality auditors’ biases [5, 6]. Given the multitude of QI tools and approaches in use, it is one of today’s major challenges to improve their compatibility with specific health systems and to take existing instruments, procedures, and data from respective health information systems into account. There is an increasing demand – not only in Kenya – to implement evidence-based QI across health systems to ensure that QI approaches, standards and indicators adhere to scientific standards [5].

In Kenya, as in many other LMIC, remarkable endeavours have been made by the government, development partners, faith based organizations and the private sector to improve service delivery, efficiency and resource utilization. However, service performance and health indicators stay behind in the Kenyan health sector.

Besides deficient infrastructure and shortages of equipment, drugs and staff problems of quality of care are prevailing. These are particularly distinctive in the areas of maternal and neonatal care, family planning and in the provision of services for the survivors of sexual and gender-based violence [7]. Hence the maternal mortality rate remains intolerably high at 362 per 100,000 live births [8]. Whereas health facility data indicated that 95.7% of pregnant women in Kenya attended at least one antenatal care (ANC) visit in 2014, the minimum of four ANC visits, as recommended by World Health Organization (WHO), was only accessed by 57.6% according to survey data. More than half of pregnant women (61%) delivered at a health facility in 2014 [9]. But even these facility-based deliveries are often performed under inadequate professional surveillance [10]. The availability and use of essential guidelines at facility level is not warranted [11]. In 2014, contraceptive prevalence was still low, with not much more than half of married women in Kenya (58%) using any method and often contraceptives are out of stock [7]. Women’s increased vulnerability to HIV infection has been particularly connected to gender based violence as a special act of defiance, the seriousness of which has been repeatedly shown in the Kenyan context [12,13,14].

In 2001 the Kenya Quality Model (KQM) was launched by the Ministry of Health (MoH) [15]. KQM defined quality management as a process to better comply with standards and guidelines, to improve structures, processes and results in health care by Quality management (QM) tools and to meet patient needs. However, KQM was not implemented in a participatory way and remained a frozen tool [16]. KQM was therefore revised, extended and renamed into Kenya Quality Model for Health (KQMH). KQMH is supposed to serve as the national framework to unify existing approaches to improve quality of care at all facilities of the health system. Although KQMH has been further developed into a comprehensive conceptual framework for QM challenges remain to operationalize KQMH. In response to this implementation gap, and as part of its support for the Kenyan health sector, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) sought to support the Kenyan Ministry of Health’s Department of Standards and Regulatory Services (DSRS) to establish a practical modality to operationalize the KQMH and make it the point of reference for all facilities working to improve the quality of their services. An integrative methodology was needed to reduce fragmentation, while an evidence-based approach was sought to strengthen the knowledge about how improving the quality of care can strengthen health systems.

A consortium including evaplan GmbH at the University of Heidelberg, the Institute for Applied Quality Improvement & Research in Health Care in Germany (aQua), and the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Research (IHPMR) in Nairobi was contracted for the development and implementation of an Integrated Quality Management System (IQMS). A first assessment of quality improvement activities that included a stakeholder mapping revealed a rather piecemeal approach to the topic of quality improvement in Kenya. Moreover, though traditional tools like supervision, the use of a Health Management Information System (HMIS) and continuous professional training were widely applied, the efforts did not produce expected results in terms of improved health outcomes.

Supervision was carried out erratically and the full potential of the approach was not exhausted. Modern quality tools like self-assessment were not well-known and little used. The completion of reporting forms was often undertaken late, the data itself was of questionable quality and the extent to which the data was used to inform health facility and sector planning limited [17].

This paper describes both the development and implementation of the IQMS and demonstrates how such an integrated quality management approach can serve as a powerful tool for decision making in poor resource settings and hence significantly improve the quality of care.

Methods

The aQua-Institute has developed a systemic, comprehensive and evidence-based Quality Management tool for the German health system. This integrated Quality Management approach has been formalized into the European Practice Assessment (EPA) and since 2013 is being implemented in more than 3000 health facilities in Germany, in the Netherlands, Belgium, Romania, Austria, Switzerland and Slovenia. It is a multiperspective, multifaceted indicator based approach that covers five domains (infrastructure, people, information, finance, and quality & safety) covering most of the six WHO health system building blocks. These domains can be modified according to the needs of the country and its health facilities.

A specially developed software (VISOTOOL®) visualizes the results in an easily understandable way to stimulate discussion with facility staff and facilitate the development of highly tailored improvement plans. Furthermore the software allows facilities to benchmark their results against the average result of all participating facilities [18, 19].

To operationalize the Kenya Quality Assurance Model for Health, EPA was adapted to leverage its integrative and evidence-based indicator-based approach in collaboration with the Ministry of Health including the Department of Standards and Regulations, the Department of Clinical Services, the Division of HMIS, the Division of Reproductive Health, the Division of Child Health and the Unit of Monitoring & Evaluation.

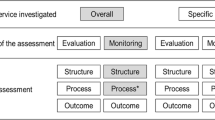

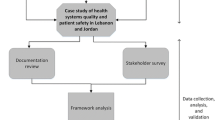

The adaptation process made use of a ten step modified RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. This systematic method to validate indicators is described in detail by Prytherch et al. [5]. The steps included a scoping workshop, definition of five critical domains of quality in the Kenyan context, and a review of more than 50 policy and planning documents, standards, management and clinical guidelines, grey and scientific literature to identify indicators in use in the Kenyan health system. An expert panel adapted and validated the five proposed domains, and assessed the identified, candidate indicators according to the Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound (SMART) criteria, before rating them on their validity and feasibility using a modified Delphi method. The resulting 303 structure, process and outcome indicators, clustered across the five domains (Clinical Care, People, Management, Interface In/out-patients, and Quality and Safety), were broken-down into 29 dimensions. For the domain Clinical Care illustrative dimensions include antenatal care, delivery, postnatal care, family planning, survivors of gender-based violence; for the domain People they include patient satisfaction, staff satisfaction, staff general, staff appraisal, staff support; for the domain Management they include leadership and governance, financial, maintenance, supplies, drugs, data, equipment, amenities, transport, waiting times; for the domain Interface In/out-patients they include community, general, referral; for the domain Quality and Safety they include general, guidelines etc., critical incident reporting, emergency management, infection control, laboratory. Finally, a set of five data collection tools based upon the final register of indicators were developed. Following the principle of triangulation of methods these tools included surveys for patients and staff, a self-assessment, facilitator assessment and a manager interview guide. The data collection tools where then incorporated into the specially developed software (VISOTOOL®). The use of quality indicators is described in detail in Goetz et al. [20] and Herrler et al. [21] (Figs. 1 and 2).

Design and sampling

A longitudinal study design was used. Ten facilities were selected out of 36 applications representing a variety of Kenyan facilities of all levels of care and from both rural and urban settings (n = 10; six hospitals (including four district hospitals and two county hospitals): Kisumu County Hospital, St. Monica’s Hospital, Bondo Sub County Hospital, Bomachage Chache Hospital, Manyala Sub County Hospital and Vihiga County Hospital; four health centers: Lynaginga Model Health Centre, Kenyerere Model Dispensary, Nyan’goma Dispensary, Shikunga Health Centre). The selection was purposeful but based on criteria like a specified minimum level of infrastructure and medical equipment for reproductive health-care provision, service provision for survivors of gender based violence, previous experience in the field of QM and motivation to invest in quality assurance in the long run. These selection criteria were to ensure the comparability between health facilities and reduce structural variables that might affect the generalisation of findings. The selected facilities were first visited in 2013 (T1) and re-visited between September 2015 and February 2016 (T2). Based on the identified gaps at T1, target-oriented improvement plans were developed with the facilities and in between the measurements several interventions were carried out in the facilities under continuous supervision.

The domain People with 85 indicators has been excluded from this analysis due to being personal data and will be published separately. All calculated values are based on the percentage achievements of the remaining 218 indicators, 24 dimensions and four domains (Clinical Care, Management, Interface In/out-patients, and Quality and Safety) at T1 and T2 on scale of 0 to 100 for each facility. All indicators, dimension and domain values of T1 and T2 for each facility have been exported from the software VISOTOOL®. Data was summarized using means and standard deviations (SDs). Categorical data was presented as frequency counts and percentages. Since the double-time data is not complete for all indicators at every facility, the calculations of the percentage changes had to be based only on those indicators with available values at both T1 and T2 at each facility. A z- testing was first considered, but due to the low data variance a t- test was felt more appropriate. p-values have been calculated in MicrosoftExcel2010 applying the one sample t-test on the mean change (difference: T2 minus T1 value) and the standard deviation. Since positive and negative changes are possible, a double-tailed event has been chosen and the expected value has been defined as a change 0, following the null hypothesis that the IQMS quality improvement has no significant impact on the T2 value for each indicator with both values. A significance level of α = 0.05 for a confidence interval of 95% has been chosen and a change (as improvement if positive or deterioration if negative) is significant if p < α, leading to a refusal of the null hypothesis.

Assessment process

The data collection tools were field tested in two facilities. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee (IREC) at Moi University, Kenya. The confidentiality of the analysis process and the fact that all responses would be depersonalized was emphasized and all participants provided informed consent.

The project was executed in two phases between 2013 and 2016. A baseline assessment was carried out during the first phase (T1) a reassessment (T2) after 1.5 years. All 10 facilities enrolled completed the first (baseline) and the second assessment.

Each assessment was implemented in two rounds making use of the above-described tools: surveys for patients and staff, a self-assessment, facilitator assessment and a manager interview guide. Experienced research assistants were used to carry out the patient survey orally in English and local languages. At least 100 responses per facility were sought from patients attending Antenatal Care, Post Natal, Family Planning and Maternity services. These surveys were complemented with the information received from the facility managers via their self-assessment. The data from these surveys was entered remotely into the VISOTOOL® software by a research assistant for analysis. A trained facilitator oversaw the facility assessment process, and the training of national “quality facilitators”. Self-assessment and patient and staff surveys were followed by a visitation through a trained facilitator, following a checklist and conducting a management interview, data was immediately entered into VISTOOL® and analysed on site.

Using VISOTOOL® the assessment was followed by an immediate and comprehensive feedback to the health facility staff. This enabled facilities to identify and focus on priority areas. Concrete and highly tailored plans of action were elaborated, preferably making use of locally available resources, including making use of existing quality improvement approaches such as KAIZEN-5S, coaching and quality circles (Tables 1 and 2).

Between T1 and T2 the facilities used the given analysis and feedback of assessment T1 results for decision-making on what intervention should be given priority and be implemented. Each of the 10 facilities then conducted a number of one to five improvement interventions based on the gaps identified and accompanied by facility-driven tutoring and coaching targeting five main topics: neonatal mortality, the completeness of partographs, waiting times, IPC as well as shortages of staffing and transportation in remote areas.

Facilities were grouped according to whether or not a concrete improvement intervention was conducted. Only those improvement intervention topics with group sizes of at least two participating and two not-participating facilities were considered as eligible for a comparison of their T1 and T2 results, in respect to those IQMS indicators matching their mentioned inducements and intervention contents (Table 3).

Results

The characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 4.

Excluding the fifth domain ‘People’, changes in the scores of the four domains and all 24 dimensions for the ten facilities at the two assessments are shown in Table 5.

Significant improvements were found in all four domains with higher scores measured in the domains ‘Clinical Care’ (10.08%; p = 0.0108), ‘Management’ (13.10%; p < 0.0001), ‘Interface In/out-patients’ (13.87%; p = 0.0246), ‘Quality and Safety’ (20.02%; p < 0.0001) and in total (14.64%; p < 0.0001).

In the domain ‘clinical care’ significant improvements were observed in the dimensions ‘Antenatal care’ (26.84%; p = 0.0059) and ‘Survivors of gender-based violence’ (11.20%; p = 0.0092). The least marked changes or even a -not significant- decline of some was found in the dimensions ‘delivery’ and ‘postnatal care’.

For the domain ‘management’ significant improvements were observed in the dimensions ‘Supplies’ (26.17%; p = 0.0145), ‘Drugs’ (12.78%; p = 0.0051), ‘Data’ (14.94%; p = 0.0403), ‘Amenities’ (12.79%; p = 0.0003) and ‘Waiting times’ (15.78%; p = 0.0369).

For the domain ‘Interface In/Out-patients’ significant improvements have been observed in the dimension ‘Referral’ (17.22% p = 0.0133). The least marked changes or even a -not significant- decline of some was found in the dimension ‘General’.

In the domain ‘quality and safety’ significant improvements were observed in the dimensions ‘Guidelines etc’ (34.18%; p = 0.0336), ‘Infection control’ (23.61%; p < 0.0001) and ‘Laboratory’ (17.30%; p < 0.0001).

The following boxplot (Fig. 3) shows the variation of all indicator changes within each domain. All mean values are within interquartile range and therefore represent the entirety of all values.

As health centres and hospitals are discussed together, a comparison of the average improvements of all 4 health centres with those of all 6 hospitals should prove that structural characteristics are not crucial for the achievement of a significant improvement (Table 6).

The differences between T1 and improvement values (= T2 values), comparing the intervention and the non-intervention groups are shown below (Fig. 4).

Looking at the results of interventions, the analysis showed for example that the improvement interventions conducted to reduce neonatal mortality achieved higher improvement rates (change) (42.33%) than the non-intervention group, where the improvement of the comparable indicators has also been significant (15.57%). Those facilities that implemented concrete activities to improve their IPC, achieved significantly higher improvements (28%) than those facilities that did not. Nevertheless, also for those facilities without concrete IPC interventions marked improvement could be observed (18%).

Discussion

To improve quality of care various factors and a combination of methods are influential, such as evidence based measurement from different perspectives, extensive feedback to staff and prioritized improvement activities. Intrinsic motivation of staff could be assumed given the selection process to participate. In the mid run, there may be external incentives to embark into a systemic quality improvement process, such as accreditation [20].

Our assumption is that a precise, detailed and participative measurement and gap analysis - as a tool for good decision-making - is a basic requirement for setting the improvement process in motion and leads to effective targeted improvement interventions which are accompanied by facility-driven coaching and tutoring. Analysis on the effectiveness of the precursor of the IQMS Kenya, EPA in Germany and Switzerland, has shown significant improvements in three of four analysed domains and demonstrated the ability of EPA as effective and efficient quality management program [6, 20].

The higher significant achievements of improvement interventions in relation to the comparison group demonstrate the effectiveness of this targeted intervention performed under facility-driven coaching and tutoring. The integral IQMS quality improvement approach demonstrated that those facilities with a combination of measurements including gap analysis, decision-making and the conduction of supervised targeted interventions achieved better improvements than facilities with the same starting conditions, but only the performance of measurement. We can thus assume, that the actual improvement can be attributed to the systemic nature of the approach.

Lower T1 values at the participating facilities – for example in the improvement interventions on waiting time and on shortages of staffing and transport in remote areas - underline the validity of the integral IQMS approach for revealing deficiencies within this area. Despite these deficiencies in comparison to the non-intervention group, all improvement interventions were able to achieve significant changes and even higher T2 values than the non-intervention group, which proves its possibility of not just catching up but overtaking by performing a previous gap analysis and prioritization of concrete interventions [6].

Furthermore, the methodological approach chosen serves different purposes of quality assessment: internal improvement, external accountability, and scientific evidence. Therefor it is paramount to measure structure, process, or outcome of healthcare.

Without looking into all details of the actual improvement process between T1 and T2 - we assume that the precise measurement of quality problems helps sensitize health staff to recognize and accept quality problems, which is also endorsed by other authors [6, 19, 22]. Being a very precise measurement method it proved to be an effective way to improve quality without any additional significant resources. Even the best T1 values in the domain ‘Management’ (68.4%), followed by the domains ‘Clinical Care’ (62.66%) ‘Interface In/out-patients’ (58.64%), and finally ‘Quality & Safety’ (51.13%) still show potential for improvement and therefore demonstrate the necessity for continuous quality improvement, one of the principles of KQMH. On the other hand the high degree of prioritizing certain interventions over others, could also explain that a dimension and the respective indicators reach lower level of improvement in comparison to others.

The approach has the power to integrate different, pre-existing and possibly competing quality improvement (QI) initiatives and to reduce the risk of indicators being reinvented. With the exception of the 44 international indicators that were retained through the review and rating process, 234 of the 303 indicators used had previously existed in the Kenyan health system. In addition to exploring clinical areas the approach offers the possibility to illuminate health system bottlenecks like drug distribution and facility accounting issues. The specially developed software (VISOTOOL®) generates real time results for immediate feedback to the facility team as an integral part of the facility visit process. Precise measurement as well as detailed display of results empower the health facility teams to better analyse underlying problems, set their quality objectives and ensure the optimal use of existing resources according to the Pareto principle. Facilities can also track their progress with the software by comparing results after each assessment. Furthermore the software allows benchmarking. Health facilities can compare their results against the average results of other facilities taking part in the assessments.

Our experience showed that this indicator based approach can be adapted to and used in different contexts and health systems.

Nevertheless, the study has limitations: T2 results might not be a pure reflection of the IQMS quality improvement process, but also be influenced by structural differences regarding staff qualification, availabilities, resources and attitude at the facilities. As to the driving factors for improvement despite structural similarities among the selected health facilities an attribution gap may exist and confounders, e.g. interferences by other health system strengthening activities, could not be excluded. Moreover it can not be clearly defined which factors and improvement activities are producing better results. This is subject of a separate analysis being in process.

Conclusion

There is a need for validated methods to measure quality of care in LMICs. In accordance with existing literature our results demonstrate that implementing a quality management system based on a systematic performance monitoring of health facilities which includes a continuous improvement process, not only breathes life into the process of collecting data for indicators, but also creates motivation for change and ownership among users and providers of health services and can serve as a powerful tool to improve health outcomes in LMIC.

As such it offers a reflection on the relevance of evidence-based quality improvement for health system strengthening and has the potential to lay a solid ground for further certification and accreditation.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- DSRS :

-

Department of Standards and Regulatory Services)

- EPA:

-

European Practice Assessment

- GIZ:

-

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HMIS:

-

Health management information system

- HSS:

-

Health system strengthening

- IHPMR:

-

Institute of Health Policy, Management and Research

- IQMS:

-

Integrated quality management system

- IREC:

-

Institutional Research Ethics Committee at Moi University, Kenya

- KQM:

-

Kenya quality model

- KQMH:

-

Kenya quality model for health

- LMIC:

-

Low and middle-income countries

- MoH:

-

Ministry of health

- QI:

-

Quality improvement

- QM:

-

Quality management

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SMART:

-

Specific measurable accepted realistic time bound

- T1:

-

Time of measurement: first assessment round in 2013

- T2:

-

Time of measurement: re-assessment in 2015/2016

- UHC:

-

Universal health coverage

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Das J. The quality of medical care in low-income countries: from providers to markets. PLoS Med. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000432.

Makinen M, Waters H, Rauch M, Almagambetova N, Bitrán R, Gilson L, McIntyre D, Pannarunothai S, Prieto AL, Ubilla G. Inequalities in health care use and expenditures: empirical data from eight developing countries and countries in transition. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(1):55–65.

Banerjee A, Deaton A, Duflo E. Health care delivery in rural Rajasthan. Econ Polit Wkly. 2004;39(9):944–9.

Berendes S, Heywood P, Oliver S, Garner P. Quality of private and public ambulatory health care in low and middle income countries: systematic review of comparative studies. PLoS Med. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000433.

Prytherch H, Nafula M, Kandie C, Brodowski M, Marx I, Kubaj S, Omogi I, Zurkuhlen A, Herrler C, Goetz K, Szecsenyi J, Marx M. Quality management: where is the evidence? Developing an indicator-based approach in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzw147.

Goetz K, Hess S, Jossen M, Huber F, Rosemann T, Brodowski M, et al. Does a quality management system improve quality in primary care practices in Switzerland? A longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2015; https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007443.

Ministry of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation (Nairobi, Kenya). Kenya service provision assessment survey 2010. In: The DHS Program: Demographic and Health Surveys. 2011. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA17/SPA17.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2017.

World Health Organization: World health statistics 2014. In: WHO library cataloguing-in-publication data. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112738/1/9789240692671_eng.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2017.

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990-2010. In:WHO library cataloguing-in-publication data. 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44874/1/9789241503631_eng.pdf. Accessed 08 May 2017.

Parkhurst JO, Penn-Kekana L, Blaauw D, Balabanova D, Danishevski K, Rahman SA, Onama V, Ssengooba F. Health systems factors influencing maternal health services: a four-country comparison. Health Policy. 2005;73(2):127–38.

Nzinga J, Mbindyo P, Mbaabu L, Warira A, English M. Documenting the experiences of health workers expected to implement guidelines during an intervention study in Kenyan hospitals. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):44.

Carter M. HIV prevalence and incidence fall in Kenya. In: NAM Aidsmap. 2014. http://www.aidsmap.com/HIV-prevalence-and-incidence-fall-in-Kenya/page/2827600/. Accessed 9 May 2017.

Fonck K, Els L, Kidula N, Ndinya-Achola J, Temmerman M. Increased risk of HIV in women experiencing physical partner violence in Nairobi, Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2005; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-005-9007-0.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya demographic and health survey 2014. In:The DHS program: demographic and health surveys. 2015. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR308/FR308.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2017.

GIZ. Quality Example. The Kenyan quality model for health - Indicator based. In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). 2013 https://www.giz.de/expertise/downloads/giz2014-en-factsheet-kenya.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2017.

Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Ministry of Medical Services, (Nairobi Kenia). Implementation guidelines for the Kenya quality model for health. WHO MiNDbank collection. 2011. https://www.mindbank.info/item/1941. Accessed 8 May 2017.

Hahn D, Wanjala P, Marx M. Where is information quality lost at clinical level? A mixed-method study on information systems and data quality in three urban Kenyan ANC clinics. Glob Health Action. 2013; https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.21424.

Engels Y, Dautzenberg M, Campbell S, Broge B, Boffin N, Marshall M, Elwyn G, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Gerlach FM, Samuelson M. Testing a European set of indicators for the evaluation of the management of primary care practices. Fam Pract. 2006;23(1):137–47.

Grol R, Dautzenberg M, Brinkmann H. Quality Management in Primary Care: European practice assessment. Verlag Bertelsmann-Stiftung. In: Stiftung Praxissiegel. 2004. http://praxissiegel.de/fileadmin/pdf/EPA-Hintergrund/Quality_Management_in_Primary_Care_2005.PDF. Accessed 8 May 2017.

Goetz K, Szecsenyi J, Broge B, Willms S. Welche Wirkung hat Qualitätsmanagement in Arztpraxen? Ergebnisse aus Entwicklung und Evaluation des Europäischen Praxisassessments (EPA) [in German]. AQUA-Verlag. In: EPA: Qualitätsmanagement in der Arztpraxis. 2011. https://epa-qm.de/epa/upload/CONTENT/Download/AQUA-EPA-Buch_2011_web.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2017.

Herrler C, Bramesfeld A, Brodowski M, Prytherch H, Marx I, Nafula M, Richter-Aairijoki H, Musyoka L, Marx M, Szecsenyi J. Integrated quality management system (IQMS): a model for improving the quality of reproductive health care in rural Kenya. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2015; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2015.02.012.

Szecsenyi J, Campbell S, Broge B, Laux G, Willms S, Wensing M, Goetz K. Effectiveness of a quality-improvement program in improving management of primary care practices. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110412.

Acknowledgments

The following individuals were participants of the multidisciplinary expert panel: Nyada C.A., Sharon J., Raburu J., Koba K., Mwangani I.M., Mwanza J., Wanjala P., Kuria N., Hambule A., Eichhorn-Wiegand A., Watindi H., Irimu G. and Karanja D. The staff and patients of the participating facilities are thanked for investing their time and thoughts in responding to the surveys.

Parts of the abstract have been presented and published at the 2017 ECTMIH – the 10th European Congress on Tropical Medicine and International Health conference on 16- 20 October 2017 in Antwerp.

Funding

The IQMS quality improvement project was supported by the Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) [Reference No. 81135455, Project No. 2010.2035.3]. This retrospectively performed research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from evaplan GmbH at the University of Heidelberg, the AQUA Institute for Applied Quality Improvement & Research in Health Care in Germany, and the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Research (IHPMR) in Nairobi, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of evaplan GmbH at the University of Heidelberg, the AQUA Institute for Applied Quality Improvement & Research in Health Care in Germany, and the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Research (IHPMR) in Nairobi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM was involved in the IQMS project, gave advice on the methods, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. CN was involved in data analysis and drafting the manuscript, MB analysed IQMS data, HP was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. MNaf, IM and MN supervised IQMS implementation and improvement interventions. CK, IO, FPF were involved in the interpretation of data and revising the manuscript. JS was involved in designing the study and indicator development. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the IQMS audits at the Kenyan facilities has been given by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee (IREC) at Moi University, Kenya. As research did not contain any individual and personalised data further retrospective analysis has been exempted from requiring ethics approval by the Ethics commission of the Faculty of Medicine Heidelberg, Germany (S-673/2015).

Written consent to participate has been given by facilities, staff members and patients previously to the IQMS data collection using questionnaires.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Marx, M., Nitschke, C., Nafula, M. et al. If you can’t measure it- you can’t change it – a longitudinal study on improving quality of care in hospitals and health centers in rural Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 18, 246 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3052-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3052-7