Abstract

Background

There is a workforce crisis in primary care. Previous research has looked at the reasons underlying recruitment and retention problems, but little research has looked at what works to improve recruitment and retention. The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate interventions and strategies used to recruit and retain primary care doctors internationally.

Methods

A systematic review was undertaken. MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL and grey literature were searched from inception to January 2015. Articles assessing interventions aimed at recruiting or retaining doctors in high income countries, applicable to primary care doctors were included. No restrictions on language or year of publication. The first author screened all titles and abstracts and a second author screened 20 %. Data extraction was carried out by one author and checked by a second. Meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity.

Results

Fifty-one studies assessing 42 interventions were retrieved. Interventions were categorised into thirteen groups: financial incentives (n = 11), recruiting rural students (n = 6), international recruitment (n = 4), rural or primary care focused undergraduate placements (n = 3), rural or underserved postgraduate training (n = 3), well-being or peer support initiatives (n = 3), marketing (n = 2), mixed interventions (n = 5), support for professional development or research (n = 5), retainer schemes (n = 4), re-entry schemes (n = 1), specialised recruiters or case managers (n = 2) and delayed partnerships (n = 2).

Studies were of low methodological quality with no RCTs and only 15 studies with a comparison group. Weak evidence supported the use of postgraduate placements in underserved areas, undergraduate rural placements and recruiting students to medical school from rural areas. There was mixed evidence about financial incentives. A marketing campaign was associated with lower recruitment.

Conclusions

This is the first systematic review of interventions to improve recruitment and retention of primary care doctors. Although the evidence base for recruiting and care doctors is weak and more high quality research is needed, this review found evidence to support undergraduate and postgraduate placements in underserved areas, and selective recruitment of medical students. Other initiatives covered may have potential to improve recruitment and retention of primary care practitioners, but their effectiveness has not been established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes a Global Health Workforce Crisis [1, 2] with many low and high income counties experiencing difficulty recruiting and retaining doctors in rural and underserved areas [2]. The WHO has described how increased availability of healthcare workers in these areas is crucial to population health [1]. The reasons behind the workforce crisis are multifactorial but aging and expanding populations and new health challenges mean that access to good quality primary care is now more important than ever [3]. In the United Kingdom (UK) the General Practice (GP) workforce crisis is having a direct effect on patient care, deprived and rural areas are particular vulnerable [4]. There are insufficient doctors to meet demands consequently up to 543 GP practices could be forced to close within the next year [5]. The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) estimated that 8000 more GPs are needed by 2020 [5] leading to the introduction of a UK target of 50 % of foundation trainees entering general practice by 2016 [6]. In the mid-1980s, general practice was the most popular career choice for medical students [7], but more recently it has become less popular than hospital medicine, with some students using it as a ‘failsafe’ or ‘backup’ career choice [8] with national applications for GP training decreasing by 6.2 % in 2015 than in the previous year [9].

Morale amongst practising primary care doctors is lower than in any other medical speciality and more are facing burnout and stress due to increasing workload and limited resources [10]. For example, in the UK 30 % of all GPs intend to leave direct patient care in the next five years [11]. The demand for part-time or flexible working patterns has increased, partly due to the increasing number of female medical practitioners, and partly due to changing expectations of both men and women [12]. Many high income countries have traditionally relied on international medical graduates (IMGs) to fill vacancies, but that is no longer possible. Despite more European-trained doctors working in the UK, the overall number of IMGs has dropped. The number of newly registered Indian doctors fell from 3640 in 2004 to 340 in 2013 [13], and 16% of overseas-qualified (outside of the European Economic Area) GPs are expected to retire over the next five to ten years [14].

Many international policies have attempted to address the problem of primary care doctor recruitment and retention [4, 15], and it is clear from other countries that significant change in a sector of a health service “requires a solid blueprint, pilot testing and evidence generation, a long-term vision, and sustained financial and political commitments“[16]. The international literature also demonstrates that it may be necessary to change the business model and professional culture in order to stabilise workforce and improve morale [17]. In the UK, £10 million has been committed by NHS England to implement a strategic ten point GP workforce action plan in 2015 in the UK [15]. Its three main areas for improvement are in recruitment, retention, and support for returning doctors. The recruitment initiative includes marketing campaign and recruitment video [18], a letter to all medical school graduates describing the positive aspects of a future career in general practice, and an additional year post training to recruit trainees to underserved areas. The report describes a three year scheme to offer financial incentives to trainees working in underserved areas. Furthermore, pilot ‘training hubs’ will offer inter-professional training to primary care staff, developing and extending the current skills base. The retention initiative includes retainer schemes and improved training capacity in general practice. Experienced GPs towards the end of their careers will be offered incentives to remain in practice, and opportunities to develop a portfolio career. Innovative ways to manage GP workload are proposed such as using physician associates, medical assistants, clinical pharmacists, and other allied health professions. A new Health Education England induction and refresher scheme aims to support GPs who have previously practiced to return to the workforce [19].

Little research has assessed the effectiveness of recruitment and retention policies for primary care doctors. The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate interventions and strategies used to recruit and retain primary care doctors internationally.

Methods

Electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL were conducted from inception to January 2015. Search terms (in English) used in MEDLINE are shown in Appendix 1. The search strategy included MESH and free text terms in three areas: 1) primary care, 2) recruitment and retention and 3) study design. Grey literature searches were undertaken in OpenSigle, internet search engines (Google and Google Scholar) and targeted websites (RCGP, Kings Fund, Health Education England, British Medical Association and specific international websites such as The Australian Government Department of Health and The World Health Organization). Specific organisations were contacted for unpublished evaluations such as Health Education England, British Medical Association and UK Local Education and Training Boards. Reference lists of the included studies and reviews were screened.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To meet the inclusion criteria, studies were required to evaluate a defined intervention aimed at recruiting or retaining doctors. Studies that included medical specialities, other than primary care were included if judged to be transferable to primary care by the three authors (PV, NS and JF). Only articles from high income countries (as defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) were included, as the issues and strategies for low and middle income countries were very different and were mainly focused on medical migration. There was no limit on study design, language or follow-up period. Studies of other health professionals, such as nurses, were excluded. All studies without a specific intervention were excluded,

Screening and data extraction

Titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer (PV) and a second reviewer (JF) screened 20 % of the total sample retrieved from the search strategy to check for concordance and to minimize bias. Unclear studies were resolved through a three way discussion (PV, NS, JF). Data extracted included study details, inclusion/exclusion criteria, study design, intervention specification costs and outcome measure. Data were extracted by one author (PV) and double checked by a second (AS).

The primary outcome was number of primary care doctors recruited or retained. Secondary outcomes were recorded when available in the included studies, these were average duration of employment after recruitment, future intentions and cost. Authors were contacted for supplementary data if necessary. The risk of bias of each study was assessed by two reviewers (PV and AS) using the Newcastle Ottowa Scale, which was modified to meet the needs of the included studies to include presence of a comparison group, generalisability, conflicts of interest and quality of reporting [20]. Studies were considered for meta-analysis, but were judged to be too heterogeneous.

Results

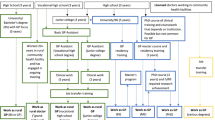

Three thousand five hundred ninety seven reports were identified from the electronic search (2753 after removal of duplicates) (Fig. 1) plus 28 from the grey literature search. After screening and eligibility assessment, 51 studies were included, describing 42 interventions. Seventeen studies were from the USA, twelve from the UK, eight from Australia, five from Canada, four from Norway, two from both Japan and New Zealand and one from Chile (Table 1).

The length of follow up ranged from one to 32 years. The number of participants included in the studies ranged from 7 to 2988. Sample sizes were generally small and 7 studies had less than 20 participants. In 8 studies the outcome was the self-reported location where the trainee or doctor was practicing after the intervention. Some studies used national databases or practice address as the outcome measure.

There were no randomised control trials (RCTs). 38 used a cross-sectional design, of which 30 did not include a comparison group, and 8 had a between-group comparison. Thirteen studies were a longitudinal design, of which six lacked a comparison group. Of the seven longitudinal comparison studies, one was a before and after comparison and six compared two parallel groups.

The representativeness of the included participants was generally good, however the absence of a comparison group resulted in a high risk of bias in many studies (Table 2). Assessment of the outcome and follow-up was generally low risk of bias. Most studies were described in an adequate or detailed manner and had potential or good generalisability. 21/51 of the included studies had a conflict of interest; primarily the study authors who undertook and evaluated the intervention were part of the same organisation that delivered the intervention.

Interventions tested

Interventions could be broadly categorised into 13 groups: retainer schemes, re-entry schemes, support for professional development or research, specialised recruiters or case managers, well-being or peer support initiatives, recruiting rural students, rural or primary care focused undergraduate placements, rural or underserved postgraduate training, marketing, delayed partnerships, international recruitment, financial incentives and mixed interventions. Results are presented from strongest to weakest evidence.

Financial incentives

The strongest evidence was for financial incentives, eleven studies evaluated interventions which provided financial incentives in return for an obligation of service [21–31]. Six studies had a comparison group [21, 22, 24, 28, 29, 31]. Two Japanese studies examined a strategy which obligated students to a nine year service agreement in their home region in exchange for fully funded undergraduate training (medical school) [21, 22]. After the nine years, students were 4.2 times more likely (no statistical significance reported) to work in rural areas compared to non-obligated students [21]. A comparative study of financial incentives compared with no financial incentives in West Virginia found similar retention rates after the obligation period (32 % 14/44 vs 38 % 41/108), with no statistical significance reported [28]. A study of five separate financial incentives found that retention rates were statistically significantly higher for obligated than non-obligated doctors (Hazard ratio 0.70 95 % CI 0.51 to 0.96) [31]. Three studies, only one of which had a comparison, assessed the National Health Service Corps (NHSC) scheme in the USA which used financial incentives, loan repayment or scholarship throughout their medical education [23–25]. The only one of these studies with a comparison group showed that NHSC participants had a lower retention rate compared to non-NHSC participants (29 % versus 52 %, p value < 0.001) [24]. One study found doctors were 3.2 times less likely to leave an underserved area if they were fulfilling a service obligation in repayment for a funding during medical school or during postgraduate training [29].

The remaining studies did not have a comparison group and were therefore difficult to draw conclusions from. A postgraduate voluntary bonding scheme in New Zealand which recruited trainees to hard-to-staff communities for five years, with payments starting after the third year and no penalty for withdrawal, found that 89 % of graduates had opted out of the scheme three years after entering [26].

Recruiting rural students

Evidence to support recruiting rural students was also found. Six studies, only one of which had a comparison group, evaluated recruiting rural students to medical school, with the expectation that some would return to their home town for practice [32–37]. The comparative study found that 68%were still practicing family medicine in the same rural area up to 16 years after graduating compared to 46 % in the comparison group (p = 0.03) [32]. While the remaining five studies [33–37] found that a large proportion of individuals recruited from rural areas subsequently work in rural areas (one study reported up to 90 %) [34], the lack of a comparison group makes it difficult to determine what would have happened if recruitment from rural areas had not taken place.

International recruitment

Four studies (three without comparison groups) evaluated international recruitment schemes [38–41]. Three initiatives waived certain visa or work requirements to enable IMGs to work in USA or Australia if they agreed to work in rural or underserved areas for an obligated period of up to ten years [39–41]. The comparative study from USA found doctors recruited entering practice without J-1 Visa Waivers in rural communities had a significantly higher retention rate than their visa waiver colleagues (p < 0.001) [40]. These schemes recruited IMGs with varied retention rates. All studies reported success in recruiting international doctors (range 7 to 145), but the three lacking of a comparison group were difficult to draw conclusions [38–41]. Three studies found that a significant number of IMGs did not stay in rural practice (73 % 19/26) [41], did not complete the three year obligation period (30 %, 22/72) [40] or did not work beyond the initial years contract (19 %, 2/7) [38].

Rural or primary care focused undergraduate placements (i.e. undergraduate placements refers to placements during medical school)

Three studies from the USA looked at rural undergraduate placements in primary care settings [42–44]. One comparative study found that 23 % (156/677) [44] of individuals with rural experience during their undergraduate were practicing in rural areas compared to 12 % (32/260) [44] of students without (statistical significance not reported). One study found a higher percentage of graduates with rural exposure in medical school subsequently worked in rural areas than those without (n = 1393, 26 % vs 7 %, p < 0.001) [43]. The final study reported a high proportion of students practicing primary care in rural areas after rural placements, but without a comparison group it is difficult to draw conclusions [43].

Rural or underserved postgraduate training

Three studies evaluated postgraduate training in rural/underserved areas [45–47]. One comparative study from the USA found that doctors who were trained in a community health centre serving underserved communities were statistically significantly more likely (odds ratio 2.7, 95 % CI 1.6 to 4.7) to work in underserved areas compared to doctors who had not [47]. Two studies from Australia did not have a comparison group but one reported that a small percentage (14 %) of individuals reported that they were influenced against rural practice after their placements [45].

Well- being or peer support initiatives

Three studies provided social and emotional support to rurally isolated doctors [48–50]. One Australian study using a before and after comparison found a moderate reduction of 5 % (98/187 compared with 102/221, statistical significance not reported) in those planning to leave rural practice after a support initiative was introduced [48]. Two studies from northern Norway reported on a tutorial group which primarily provided support for postgraduate

doctors serving an internship in a rural area [49, 50]. The authors found good recruitment (twice as many as expected) [49] and retention (65 % five year retention) [50], but the results were confounded by place of graduation and growing up in that area making it impossible to disaggregate the effects of the tutorial group.

Marketing

Two studies evaluated marketing strategies for recruiting residents to a primary care training program [51, 52]. A promotional video marketing in the USA was associated with lower recruitment with only 29 % (35/120) of those receiving the video applied compared to 54 % (69/128) of those who did not (p < 0.0001) [51]. In a non-comparative study, 48 % of trainees recruited in the North of Scotland study stated that a blog which posted views and experiences of current primary care trainees positively influenced their choice of location for primary care training [52].

Mixed incentives

Weak evidence was found for mixed incentives. Five small studies [53–57] evaluated mixed incentives, combining continued medical education, financial and undergraduate placement incentives to recruit and retain doctors, with mixed results. None of the studies included a comparison group and therefore it is difficult to draw conclusions about either individual components or the intervention as a whole.

Two of these studies evaluated one scheme in Alberta, which used financial incentives, CME and rotations aimed at undergraduates, postgraduates and currently practicing doctors [56, 57] 35 % indicated the scheme had a critical or moderate effect on their decision to move or stay in Alberta but after the scheme was initiated the number of rural primary care doctors in Alberta actually reduced [56].

Support for professional development and academic opportunities

Five studies, without a comparison group, focused on interventions which aimed to provide primary care doctors with an increase in academic skills, particularly in teaching and research [58–62]. Three studies reported the London Initiative Zone Educational Incentive scheme (LIZEI) aimed to improve recruitment, retention and refreshment of London GPs via various schemes which focused on increasing the academic aspect of training through academic/research associate schemes [58–60]. The scheme reported high levels of retention (75 % from the London Academic Training Scheme (LATS) cohort continued to practice in London) [58], but the lack of a comparison group makes this difficult to interpret, two further studies echoed this result, and found high levels of retention in London [59, 60]. The two other studies were from Australia [61, 62]. One found that 80 % of attendees (341/426) of continuing medical education (CME) workshops reported that they were less likely to remain in rural practice without CME [62]. The other study lack sufficient detail to allow interpretation of the results [61].

Retainer schemes

Four studies, without a comparison group, assessed retainer schemes in the UK, including the Women’s Doctors Retainer Scheme [63, 64], the GP retainer scheme [65] and the Doctors’ retainer scheme [66]. Retainer schemes allow primary care doctors to work reduced hours (a maximum of four sessions a week, a minimum of one) with an educational component, for up to five years. Participants from a retainer scheme in Scotland reported that the scheme prevented them leaving medicine (32 % of former members (33/104) and 46 % of current members (69/152) [66]. All studies showed high retention of primary care doctors from retainer schemes (86 % (91/105) [65], 91 % (33/36) [63] and 71 % (10/14) [64] but the lack of a comparator group made it difficult to draw conclusions about the effect of the scheme.

Re-entry schemes

One small study [67] with a comparison group evaluated a re-entry scheme, developed to help doctors to return to general practice as a partner (i.e. partner is a term used in the UK for a GP who makes a financial investment into a practice, and can therefore benefits from any profits (or losses) it makes, they must also oversee how the practice is run). The scheme rebuilt their confidence using needs based tutorials. Six months after the course 2 out of 14 attendees had returned to working as partners. 11 out of 14 attendees had taken ‘positive steps’ (this was not explained further) to return to general practice or had increased their time commitment to medicine. Compared with 1 in the control group (comparison group denominator not reported), who had ‘made plans’ to return to general practice [67]. The numbers were too small to draw conclusions.

Delayed partnership

Weak evidence was found for the value of delayed partnerships. Two studies without comparison groups looked at delaying partnership after GP training by adding up to two years of post-vocational training [68, 69]. This included sessions at a mentor practice gaining general experience, varied locum experience and protected time for further training education [68]. Another scheme added one year of extra training which included exposure to the financial, managerial aspects of partnership, as well as clinical time [69]. The lack of a comparison group made it impossible to draw conclusion about the effectiveness of delayed partnerships.

Specialised recruiter or case managers

The weakest evidence was found for specialised recruiters or case managers. Two cross sectional studies (non-comparative) used specialised recruiters or case managers to recruit doctors to rural areas [70, 71]. They provided a holistic approach to recruitment, identifying any particular needs of the doctor, helping to support them through the transition and encouraging community development activities. While both studies reported successful recruitment (17 doctors in 18 months [71] and 8 primary care providers in two years [70]), the impact of a case manager is unclear without a comparison group. A bachelor’s degree in a health related field plus health related work experience (two years minimum) was required for the specialised recruiter post in the USA, but was not compulsory [70].

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to assess interventions to improve recruitment and retention of primary care doctors. The studies were all of low methodological quality, and only 15 of the 51 included studies involved a comparison group. There is weak evidence from these 15 studies that improved recruitment of primary care doctors was associated with postgraduate placements in underserved areas, undergraduate rural placements and recruiting students to medical school from rural areas. There was weak mixed evidence about financial incentives. The quality of the studies was not sufficient to draw conclusions about retainer schemes, re-entry schemes, international recruitment, specialised recruiters, support for professional development or research, delayed partnerships, well-being or peer support or mixed approaches.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this review included that an inclusive search was undertaken with a robust process for screening and extraction of data. Grey literature was extensively searched and yielded six additional studies. Authors were contacted when necessary and this resulted in two additional studies. The methodological quality was assessed using a modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale, to elicit particular methodological problems. The response rate for the questionnaire based studies varied between 55 and 100 %. An online survey achieved a 100 % (24/24) response rate [46].

The methodological quality of the included studies was low as there were no RCTs and many of the studies did not include a control group or comparator. 21/51 of the included studies had some conflict of interest.

Studies without a defined intervention were excluded, this may have restricted our search however we wanted to evaluate how well interventions worked, not simply find relationships or factors which influence recruitment and retention. In eight studies the outcome was the self-reported location of where the trainee or doctor was practicing after the intervention, which may be open to reporting bias.

Sample sizes were generally small and 7 studies had less than 20 participants, which may affect the generalisability of the results. Some studies may have been affected by selection bias as for example students with an interest in rural medicine and intentions to continue with it may be more likely to join a rural based university or program.

Many of the interventions were tested in the USA, Canada or rural Australia. Whilst this may limit generalisability to other countries and health systems, the principles and theory behind the interventions such as providing placements in underserved areas should be considered for undergraduate and postgraduate training for primary care may be transferable. There was great variability in reported outcome measures and ‘retention rates’. Some studies regarded the intention to stay in the area after an intervention as retention, whilst others considered the length of duration post- intervention as retention. The heterogeneity of outcome measure made comparison between studies difficult and meta-analysis impossible.

Comparison with previous research

Previous systematic reviews of strategies to increase attraction and retention of health workers in rural areas found some evidence to support the use of financial incentives, and insufficient evidence for increasing professional support, support for medical education and educational initiatives [72, 73]. A systematic review of recruitment and retention of primary care doctors in rural Canada and Australia found that factors before medical school were associated with future practice location, and that those who had been bought up or completed high school in rural areas were subsequently more likely to work there [72]. Rural experiences in postgraduate training, financial incentives, and support for professional development were found to be valuable [72].

Comparison of our findings with existing recommendations

In the UK the 10 Point Plan [15] plans to introduce an additional flexible year, after completion of training to recruit trainees to underserved areas is planned [15]. This was supported by our research which found that doctors who completed their training in underserved areas were statistically significantly more likely to practice there. The report also sets out a plan to explore a three year financial incentive scheme to offer additional financial support to GP trainees committed to working in underserved areas [15]. Our research found mixed results for the use of financial incentives. They were found to be particularly successful when tying in trainees who had existing links to the underserved area [21], and when there is a long period of service obligation and more flexibility in career opportunities [21, 22, 62]. Financial incentives may need to be tied into public sector service with clear guards against direct personal profit.

A new induction and refresher scheme has been recently introduced in the UK by Health Education England and aims to support GPs to return to the workforce in England [16]. The GP taskforce final report recommends funding of a returners scheme – prioritising funding in under-doctored areas [4]. Our research did not find sufficient evidence to support or refute this. A marketing campaign is set to be implemented (a recruitment video outlining the positive aspects of general practice has already been distributed by RCGP). Our research found that video marketing may have a negative effect on recruitment.

Implications for research and policy and conclusions

Despite the large number of reports and studies on the primary care doctors workforce crisis, and papers describing factors which influence recruitment and retention there is little evidence about which interventions are actually effective. As is pointed out in the recommendations of the Roland Commission [74], policy makers and health planners cannot learn from previous initiatives without published high quality evaluation, and unsuccessful strategies risk being reintroduced repeatedly, and consequently substantive amounts of funding wasted.

The evidence from this review also suggests that selection and educational exposures are important and that students are likely to be retained in a rural or underserved area if they have connections to the area, and are exposed to good educational primary care placements. Despite the recruitment crisis, clinical time as an undergraduate remains dominated by hospitals in many UK medical schools, and there is a great disparity between the numbers of graduates who eventually training as GPs. The 2015 F2 Career Destination Report shows that some UK universities are producing significantly more graduates who go on and apply to GP training than others, with Oxford and Cambridge behind others (see Table 3) [75]. Medical schools have a responsibility to start taking notice of the workforce crisis in primary care and perhaps resources and funding for these Universities should be based on output to meet targets. Furthermore if the UK is to meet the targets of 50 % of medical students entering primary care, we must consider more medical school training to be in GP and resources to support this must be provided. Universities should be held accountable as to how much time they allocate to the primary care setting and this data should be made publically available. The current work plan for primary care doctors is outdated, there is a need for change to reflect the change in the workforce. As the recruitment crisis worsens we believe these methods should be trialled on a larger scale.

More research is needed to identify evidence-based solutions to the primary care doctor workforce crisis and specific interventions to encourage more doctors into deprived areas that are currently under-served. Evaluations should be designed into all new recruitment initiatives and should include a comparison group (e.g. before and after, multicentre comparative, or formal trial) and these should then be made publically available. Retention based initiatives/interventions must also be tested to help streamline the current process of qualified GPs returning to work after a career break, and to help aid the loss of doctors to overseas positions, or those choosing to leave the profession entirely. Novel theory-based strategies such as case managers, improved support for professional development, and well-being and peer support should be evaluated.

Conclusions

Although the evidence base for recruiting and retaining primary care doctors is weak and more high quality research is needed, this review found evidence to support undergraduate and postgraduate placements in underserved areas, and selective recruitment of medical students. The other initiatives covered in this review all have potential to improve recruitment and retention of primary care practitioners, but their effectiveness is not yet established.

Ethical approval

None required. No primary data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data

No additional data available.

Abbreviations

- AS:

-

Arabella Stuart

- CME:

-

continuing medical education

- GP:

-

general practitioner

- IMG:

-

international medical graduates

- JF:

-

John Ford

- LATS:

-

London Academic Training Scheme

- LIZEI:

-

London Initiative Zone Educational Incentive Scheme

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NHSC:

-

National Health Service Corps

- NS:

-

Nick Steel

- PV:

-

Puja Verma

- RCGP:

-

Royal College of General Practitioners

- RCT:

-

randomised controlled trial

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Report 2006: Working together for health; Geneva; 2006.p.1–209 http://www.who.int/whr/2006. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Global Health Workforce Alliance. Global Health Workforce Crisis: Key Messages Geneva, Switzerland; 2013.p.15. http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/media/KeyMessages_3GF.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

World Health Report: Primary Health Care (Now More Than Ever). World Health Organization Geneva, Switzerland; 2008.p.1–122. http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

GP Taskforce. Securing the future GP workforce. Delivering the mandate on GP expansion. GP taskforce final report; 2014.p.1–63 https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/GP-Taskforce-report.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). Over 500 surgeries at risk of closure as GP workforce crisis deepens RCGP; 2014. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/news/2014/october/over-500-surgeries-at-risk-of-closure-as-gp-workforce-crisis-deepens.aspx. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Department of Health (DOH). Delivering high quality, effective, compassionate care: Developing the right people with the right skills and the right values; 2013.p.1-40 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/203332/29257_2900971_Delivering_Accessible.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Petchey R, Williams J, Baker M. ‘Ending up a GP’: a qualitative study of junior doctors’ perceptions of general practice as a career. Fam Pract. 1997;14:194–8.

Abbt N, Alderson S. Why doesn’t anyone want to be a GP: and what can we do about it? Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:579–79.

Health Education East of England. Primary care workforce development; HEEoE: update to board 28th January 2015.

British Medical Association (BMA). BMA quarterly tracker survey. 2014. http://bma.org.uk/working-for-change/policy-and-lobbying/training-and-workforce/omnibus-survey-gps. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Hann M, McDonald J, Checkland K, Coleman A, Gravelle H, Sibbald B, et al. Seventh national GP worklife survey. Aug 2013. http://www.population-health.manchester.ac.uk/healtheconomics/research/reports/FinalReportofthe7thNationalGPWorklifeSurvey.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Department of Health (DOH). Report of the Chair of theNational Working Group on Women in Medicine. Women doctors: making a difference; 2009.p.1–73 www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_106894. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Sidhu K. Overseas doctors and the GP recruitment crisis. BMJ Careers. 2014. http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20020042. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

The King’s Fund. Improving the Quality of Care in General Practice. Independent inquiry into the quality of care in general practice in England; 2011.p.1–169 www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/gp_inquiry_report.html. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

NHS England, HEE, RCGP, BMA, Building the Workforce – the New Deal for General Practice 2015. http://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/01/building-the-workforce-new-deal-gp.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

James M, Harris MJ. Brazil's family health strategy — delivering community-based primary care in a universal health system. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2177–81. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1501140.

Thorlby R, Smith J, Barnett, Mays N. Primary Care for the 21st Century: Learning from New Zealand’s Independent Practitioner Associations. Nuffield Trust, 2012. http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/publication/new_zealand_ipas_260912-update.pdf. Accessed 22 Jun 2015.

Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). Future GP: Recruitment Video. 2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U2YaTKDAMXs&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

NHS England, HEE, RCGP, BMA. Building the workforce—the new deal for general practice. The GP Induction & Refresher Scheme 2015–2018; 2015. https://gprecruitment.hee.nhs.uk/Induction-Refresher. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Ottowa Hospital Research Institute. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses; 2014.http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Kajii E. A contract-based training system for rural physicians: follow-up of Jichi Medical University graduates (1978–2006). J Rural Health. 2008;24:360–8.

Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Kajii E. Long-term effect of the home prefecture recruiting scheme of Jichi Medical University, Japan. Rural Remote Health. 2008;8:930.

NHSC Corps [online]. NHSC Clinician Retention: A story of dedication and commitment. Secondary NHSC Clinician Retention: A story of dedication and commitment; 2012. : https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/currentmembers/membersites/retainproviders/retentionbrief.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Pathman DE, Konrad TR, Ricketts 3rd TC. The comparative retention of National Health Service Corps and other rural physicians. Results of a 9-year follow-up study. JAMA. 1992;268:1552–8.

Cullen TJ, Hart LG, Whitcomb ME, Rosenblatt RA. The National Health Service Corps: rural physician service and retention. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10:272–9.

New Zealand Ministry of Health. Voluntary Bonding Scheme; 2012. http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/health-workforce/voluntary-bonding-scheme Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Dunbabin JS, McEwin K, Cameron I. Postgraduate medical placements in rural areas: their impact on the rural medical workforce. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6:481.

Jackson J, Shannon CK, Pathman DE, Mason E, Nemitz JW. A comparative assessment of West Virginia’s financial incentive programs for rural physicians. J Rural Health. 2003;19(Suppl):329–39.

Mathews M, Heath SL, Neufeld SM, Samarasena A. Evaluation of physician return-for-service agreements in Newfoundland and Labrador. Healthcare Policy Politiques de sante. 2013;8:42–56.

Nichols N. Evaluation of the Arizona Medical Student Exchange Programe. J Med Educ. 1977;52:817–23.

Pathman DE, Konrad TR, King TS, Taylor DH, Koch GG. Outcomes of states’ scholarship, loan repayment, and related programs for physicians. Med Care. 2004;42:560–8.

Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Rabinowitz C. Long-term retention of graduates from a program to increase the supply of rural family physicians. Acad Med. 2005;80:728–32.

Mathews M, Rourke JT, Park A. The contribution of Memorial University’s medical school to rural physician supply. Can J Rural Med. 2008;13:15–21.

Quinn KJ, Kane KY, Stevermer JJ, Webb WD, Porter JL, Williamson HA, et al. Influencing residency choice and practice location through a longitudinal rural pipeline program. Acad Med. 2011;86:1397–406.

Landry M, Schofield A, Bordage R, Belanger M. Improving the recruitment and retention of doctors by training medical students locally. Med Educ. 2011;45:1121–9.

Magnus JH, Tollan A. Rural doctor recruitment: does medical education in rural districts recruit doctors to rural areas? Med Educ. 1993;27:250–3.

Stearns JA, Stearns MA, Glasser M, Londo RA. Illinois RMED: a comprehensive program to improve the supply of rural family physicians. Fam Med. 2000;32:17–21.

Bregazzi R, Harrison J. From Spain to County Durham; experience of cross-cultural general practice recruitment. Educ Prim Care. 2005;16:268–74.

Kahn TR, Hagopian A, Johnson K. Retention of J-1 visa waiver program physicians in Washington State’s health professional shortage areas. Acad Med. 2010;85:614–21.

Crouse BJ, Munson RL. The effect of the physician J-1 visa waiver on rural Wisconsin. WMJ. 2006;105:16–20.

Robinson M, Slaney GM. Choice or chance! The influence of decentralised training on GP retention in the Bogong region of Victoria and New South Wales. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13:2231.

Halaas GW, Zink T, Finstad D, Bolin K, Center B. Recruitment and retention of rural physicians: outcomes from the rural physician associate program of Minnesota. J Rural Health. 2008;24:345–52.

Smucny J, Beatty P, Grant W, Dennison T, Wolff LT. An evaluation of the Rural Medical Education Program of the State University Of New York Upstate Medical University, 1990–2003. Acad Med. 2005;80:733–8.

Adkins RJ, Anderson GR, Cullen TJ, Myers WW, Newman FS, Schwarz MR. Geographic and specialty distributions of WAMI Program participants and nonparticipants. J Med Educ. 1987;62:810–7.

Charles DM, Ward AM, Lopez DG. Experiences of female general practice registrars: are rural attachments encouraging them to stay? Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13:331–6.

Wearne S, Giddings P, McLaren J, Gargan C. Where are they now? The career paths of the remote vocational training scheme registrars. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39:53–6.

Morris CG, Johnson B, Kim S, Chen F. Training family physicians in community health centers: a health workforce solution. Fam Med. 2008;40:271–6.

Gardiner M, Sexton R, Kearns H, Marshall K. Impact of support initiatives on retaining rural general practitioners. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14:196–201.

Straume K, Shaw DM. Internship at the ends of the earth - a way to recruit physicians? Rural Remote Health. 2010;10:1366.

Straume K, Sondena MS, Prydz P. Postgraduate training at the ends of the earth - a way to retain physicians? Rural Remote Health. 2010;10:1356.

Barclay 3rd DM, Lugo V, Mednick J. The effects of video advertising on physician recruitment to a family practice residency program. Fam Med. 1994;26:497–9.

Green P. The effect of a blog on recruitment to general practitioner specialty training in the north of Scotland. Educ Prim Care. 2015;26:113–5.

Steinert S. Proceedings of the WONCA Conference; 2010 Recruiting and Retaining GPs to remote areas in Northern Norway: The Senja Doctor Project: University of Tromso. Cancun, Mexico http://www.nsdm.no/filarkiv/File/presentasjoner/WONCA_2010_Svein_Steinert.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Pena S, Ramirez J, Becerra C, Carabantes J, Arteaga O. The Chilean Rural Practitioner Programme: a multidimensional strategy to attract and retain doctors in rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:371–8.

Wilson DR, Woodhead-Lyons SC, Moores DG. Alberta’s Rural Physician Action Plan: an integrated approach to education, recruitment and retention. CMAJ. 1998;158:351–5.

Czapski P. Rural incentive programs: a failing report card. Can J Rural Med. 1998;3:242–7.

Anderson M, Rosenberg MW. Ontario’s underserviced area program revisited: an indirect analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:35–44.

Hilton S, Hill A, Jones R. Developing primary care through education. Fam Pract. 1997;14:191–3.

Freeman G, Fuller J, Hilton S, Smith F et al. Academic Training in London. In: GP Tomorrow, Harrison J and Van Zwanberg T editors. Abingdon, Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002. p. 117–125.

Bellman L. Whole-system evaluation research of a scheme to support inner city recruitment and retention of GPs. Fam Pract. 2002;19:685–90.

Wilkinson D, Symon B, Newbury J, Marley JE. Positive impact of rural academic family practices on rural medical recruitment and retention in South Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2001;9:29–33.

White CD, Willett K, Mitchell C, Constantine S. Making a difference: education and training retains and supports rural and remote doctors in Queensland. Rural Remote Health. 2007;7:700.

Beaumont B. Special provisions for women doctors to train and practise in medicine after graduation: a report of a survey. Med Educ. 1979;13:284–91.

Eskin F. Review of the women doctors’ retainer scheme in the Sheffield region 1972–73. Br J Med Educ. 1974;8:141–4.

Lockyer L, Young P, Main PG, Morison J. The GP retainer scheme: report of a national survey. Educ Prim Care. 2014;25:338–46.

Douglas A, McCann I. Doctors’ retainer scheme in Scotland: time for change? BMJ. 1996;313:792–4.

Baker M, Williams J, Petchey R. Putting principals back into practice: an evaluation of a re-entry course for vocationally trained doctors. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47:819–22.

Harrison J, Redpath L. Career Start in County Durham. In: GP Tomorrow. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002. p. 59–74.

Delacourt L, Savage R. South London VTA Scheme seven years on. In: GP Tommorow. Harrison J and Van Zwanberg T editors. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002. p. 105–114.

Felix H, Shepherd J, Stewart MK. Recruitment of rural health care providers: a regional recruiter strategy. J Rural Health. 2003;19(Suppl):340–6.

MacIsaac P, Snowdon T, Thompson R, Wilde T. Case management: a model for the recruitment of rural general practitioners. Aust J Rural Health. 2000;8:111–5.

Viscomi M, Larkins S, Gupta TS. Recruitment and retention of general practitioners in rural Canada and Australia: a review of the literature. Can J Rural Med. 2013;18:13–23.

Dolea C, Stormont L, Braichet JM. Evaluated strategies to increase attraction and retention of health workers in remote and rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:379–85.

The Future Primary Care Workforce : creating teams for tomorrow. Report of the Primary Care Workforce Commission. London: HEE; 2015.

The UK Foundation Programme Office. National F2 Career Destination Report 2015. http://www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk/pages/home/keydocs. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Howard and Krishna Kasaraneni for their helpful comments.

Protocol

Not published.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, AH is an Officer of the RCPGP and has national involvement with Health Education England, SE is a Trustee of the Kings Fund, Chair of Tower Hamlets CCG, Advisor to NHS England and member of the BMA Council but none of these relationships of AH or SE have influenced the submitted work.

Authors’ contributions

JF conceived the idea. All authors contributed to the design of the study. PV, JF and AS screened titles and abstracts and extracted data with help from NS. JF and NS supervised day-to-day activities. NS and AH provided detailed editorial comment and policy guidance, and SE provided clinical expertise throughout. PV and AS carried out risk of bias for all studies. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results. PV drafted the initial manuscript and all authors were involved in revising and agreeing the final manuscript. JF is the guarantor and affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

MEDLINE search strategy

-

1.

exp physician/

-

2.

exp general practice/

-

3.

general practitioner*.tw.

-

4.

(family adj doctor*).tw.

-

5.

GP*.tw.

-

6.

general practitioner/

-

7.

physicians, family/

-

8.

physicians, primary care/

-

9.

doctor*.tw.

-

10.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

-

11.

exp personnel selection/

-

12.

(recruit* adj2 (GP* or doctor* or (medical adj (personnel or staff or professional* or worker*)) or (General adj practitioner*) or (family adj physician*) or (family adj doctor*))).tw.

-

13.

(retain* adj2 (GP* or doctor* or (medical adj (personnel or staff or professional* or worker*)) or (General adj practitioner*) or (family adj physician*) or (family adj doctor*))).tw.

-

14.

(retention* adj2 (GP* or doctor* or (medical adj (personnel or staff or professional* or worker*)) or (General adj practitioner*) or (family adj physician*) or (family adj doctor*))).tw.

-

15.

11 or 12 or 13 or 14

-

16.

10 and 15

-

17.

limit 16 to humans

Search strategy EMBASE 3/12/14

-

1.

exp physician/

-

2.

exp general practice/

-

3.

general practitioner*.tw.

-

4.

(family adj doctor*).tw.

-

5.

GP*.tw.

-

6.

general practitioner/

-

7.

physicians, family/

-

8.

physicians, primary care/

-

9.

doctor*.tw.

-

10.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

-

11.

(recruit* adj2 (GP* or doctor* or (medical adj (personnel or staff or professional* or worker*)) or (General adj practitioner*) or (family adj physician*) or (family adj doctor*))).tw.

-

12.

(retain* adj2 (GP* or doctor* or (medical adj (personnel or staff or professional* or worker*)) or (General adj practitioner*) or (family adj physician*) or (family adj doctor*))).tw.

-

13.

(retention* adj2 (GP* or doctor* or (medical adj (personnel or staff or professional* or worker*)) or (General adj practitioner*) or (family adj physician*) or (family adj doctor*))).tw.

-

14.

*personnel management/

-

15.

11 or 12 or 13 or 14

-

16.

10 and 15

-

17.

limit 16 to human

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Verma, P., Ford, J.A., Stuart, A. et al. A systematic review of strategies to recruit and retain primary care doctors. BMC Health Serv Res 16, 126 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1370-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1370-1