Abstract

Background

Patients with ACS often present to community hospitals without on-site cardiac catheterization and revascularization therapies. Transfer to specialized cardiac procedural centers is necessary to provide access to these procedures. We evaluated process of care within a regional care model by comparing cardiac catheterization and revascularization rates and outcomes in ACS patients presenting to community and interventional hospitals.

Methods

We evaluated a total of 6154 patients with ACS admitted to Southern Alberta hospitals (where a distinct regional care model for ACS exists) between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009. We compared cardiac catheterization and revascularization rates during index hospitalization among patients admitted to community and interventional hospitals. Thirty day and 1-year survival were also evaluated.

Results

Catheterization was performed more often in patients presenting to community hospitals compared to the interventional facility (respectively 69.5% and 51.4%, p < 0.0001). Catheterization within 72 hours of admission occurred in 48% of patients presenting to the interventional center and in 68.3% of community patients (P < 0.0001). In patients undergoing catheterization, revascularization (PCI and/or CABG) was also performed more frequently in the community group (74.5% vs 56.1%, P < 0.0001). Risk adjusted mortality rates were the same for patients undergoing cardiac catheterization regardless of hospital of initial presentation.

Conclusion

ACS patients presenting to community centers associated with a regional care model had effective access to cardiac catheterization and revascularization. These findings support the importance of regional initiatives and processes of care that facilitate access to cardiac catheterization for all ACS patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) represent a common cause for hospital admissions and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease. In patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), an early invasive strategy, in patients without contraindications or prohibitive comorbidities, is superior to a selective invasive strategy in reducing rehospitalization and myocardial infarction (MI) [1],[2]. Indeed, guidelines endorse an early invasive strategy defined as cardiac catheterization and revascularization within 48-72 hours of presentation for high-risk patients [3]-[6]. However, patients with ACS usually present to the nearest acute care facilities for evaluation and management. These are often community hospitals that lack cardiac catheterization and revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] and coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) abilities. Efficient inter-hospital transfer between community and tertiary centers is therefore necessary to provide access to these procedures. Previous studies have demonstrated that a significant number of ACS patients in the community do not get transferred to interventional capable centers for invasive management [7]-[9].

We have developed a large, population-based clinical registry that captures all patients undergoing cardiac catheterization and revascularization in Alberta, Canada since 1995. The subsequent expansion of this registry to include all cardiac admissions in Southern Alberta provides a unique opportunity to examine practice patterns (such as transfer for cardiac catheterization) and outcomes in unselected ACS patients. The purpose of this study was to evaluate process of care within a regional care model by comparing cardiac catheterization and revascularization rates and outcomes in ACS patients presenting to community and interventional hospitals.

Methods

All data were derived from the Alberta Provincial Program for Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart disease (APPROACH). APPROACH is an ongoing prospective cohort study of all Alberta residents undergoing cardiac catheterization for coronary artery disease since 1995, which expanded in 2004 to include cardiac admissions in Southern Alberta. The initiative has been previously described [10]. In brief, this population-based, multiple-year inception cohort database contains detailed information on socio-demographic characteristics, presence of risk factors and comorbidities, disease-specific variables, coronary catheterization results, post-catheterization referral decisions, records of actual revascularization and long-term outcomes including survival and quality of life. Data from APPROACH are routinely enhanced by merging the clinical registry data to administrative records to supplement clinical information available on all patients. This data enhancement methodology has been validated and previously reported [11]. Patient survival from catheterization and/or revascularization until death is ascertained through semi-annual linkage to Alberta Vital Statistics records. The APPROACH registry has an approved privacy impact assessment. The University of Calgary and University of Alberta Research Ethics Boards have approved APPROACH registry data collection and linkages with secondary sources.

For the present study we identified all patients over the age of 18 with ACS (NSTEMI and unstable angina (UA)) admitted to hospitals in Southern Alberta. This region is a large geographic area of over 1.6 million people served by one interventional center in the city of Calgary with a constellation of smaller community hospitals in surrounding areas. This Calgary Health Region is one of the largest, fully integrated health care systems in Canada.

Patients were categorized according to location and facilities available in the hospital of initial admission: 1) community hospitals: comprised of secondary referral centers staffed by specialists and/or general practitioners and smaller primary centers without on-site specialty physicians. All community centers lack on-site cardiac catheterization facilities and are located a minimum of 49 kilometers (km) and a maximum of 291 km (average 220 km) from the interventional center, 2) interventional hospital: the only tertiary care center with on-site cardiac catheterization and revascularization abilities and cardiology specialists. Each rural region has independent ACS management protocols, however, when a patient requiring cardiac catheterization is identified, referring physicians complete a standard referral form that is sent to the catheterization center by fax, along with relevant history, GRACE score, laboratory data, and other tests if applicable. When the referral is complete, it is reviewed by a member of the interventional cardiology group for approval and triage for urgency and arrangements for transport to the interventional center are made.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes of interest were cardiac catheterization and revascularization rates during index admission among patients admitted to community versus interventional hospitals. Baseline comparisons of clinical characteristics between patient groups were made by the Chi Square Test for categorical variables and by ANOVA for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to present the unadjusted thirty-day and one-year survival rates from the index hospitalization for each patient group. Cox proportional hazard models were then used to calculate survival following risk adjustment for the clinical characteristics and comorbidities presented in Table 1. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2, (Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Our cohort consisted of 6154 ACS patients admitted to hospitals in Southern Alberta between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009. Of these patients, 2592 (42.1%) were admitted initially to community hospitals and 3562 (57.9%) to the interventional center. Baseline patient characteristics were analyzed according to type of admitting hospital (Table 1) and cardiac catheterization status (Table 2). Smoking, dyslipidemia, previous heart failure, initial diagnosis of NSTEMI and the presence of dynamic electrocardiogram changes were all more prevalent in patients admitted to community hospitals. Patients admitted to the interventional hospital more commonly had a history of previous revascularization (PCI /CABG) and were more likely to be on dialysis than those admitted to community hospitals.

Figure 1 depicts cardiac catheterization and revascularization rates according to type of admitting hospital. Catheterization was performed more frequently in patients initially admitted to community hospitals than those admitted initially to the interventional facility (respectively 69.5% and 51.4%, p < 0.0001). In patients undergoing catheterization, revascularization (PCI and/or CABG) was also performed more frequently in the community group compared to the interventional group (respectively, 74.5% and 56.1%, P < 0.0001). The overall mean time to cardiac catheterization was 3.2 days. Patients admitted to the interventional center underwent catheterization sooner than those admitted to community centers (2.6 vs. 4 days, p < 0.001). In the interventional group, 9.8% underwent catheterization within 24 hours of admission compared to 16.7% in the community group. Within 48 hours from admission, 32.5% and 54.3% of the interventional and community patients underwent catheterization and within 72 hours, 48% and 68.3% had undergone the procedure (p < 0.0001).

Cardiac catheterization and revascularization rates by presenting hospital (Revascularization defined as percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting). Catheterization: Int 1,832 (51.4%) vs. comm 1,801 (69.5%), P<0.0001.Revascularization: Int 1,027 (56.1%) vs. comm 1,342 (74.5%), P<0.0.

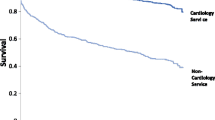

Figure 2 demonstrates Kaplan Meier survival curves extending to one year of follow up. There was an early separation of the curves that persisted with longer follow-up, with crude mortality rates significantly lower in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization in both community (12.7% vs. 3.5%) and interventional (9.1% vs. 4.2%) centers p < 0.0001. Survival was lower for patients not referred for catheterization from an admitting community hospital compared to patients first admitted to the interventional center but not referred for catheterization (87.3% vs. 90.9%, p = 0.003).

Table 3 demonstrates crude and adjusted hazard ratios for our cohort. After adjusting for baseline risk factor characteristics seen in Table 1, no difference in outcome at 30 days or 1 year was noted between those admitted to the interventional center and those initially admitted to community centers.

Discussion

This analysis from a large cohort of geographically diverse patients indicates that regionalization of tertiary ACS services enables access to cardiac catheterization for patients from community centers. Indeed, within this regional care model, patients presenting initially to community hospitals actually had higher rates of cardiac catheterization and revascularization than those presenting initially to the interventional center, and underwent these procedures in a timely fashion.

The advantages of regional care centers for the treatment of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) have been clearly described [12]-[14]. Regional approaches to STEMI care focus on rapid identification and early reperfusion therapy with the goal of reducing morbidity and mortality. The essential components of regional STEMI care plans include detailed treatment and transfer protocols, community planning, resources, education, quality improvement analysis and research [15]. Likewise, the development of regionalized comprehensive stroke centers for the care of patients with acute stroke has addressed disparities in the delivery of stroke services particularly between urban and rural centers [16]-[18].

Few studies have evaluated the regionalization of care for patients with NSTEMI, particularly in the geographically robust provinces of Canada. The Heart Protection Partnership (HPP) project was an Australian initiative developed to audit compliance with evidence-based treatments in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated at interventional and non-interventional centers across the country. The program identified treatment gaps, particularly in non-interventional centers, and provided feedback to individual centers with the purpose of improving compliance with benchmark standards of care [19]. Ideally, regional centers for ACS should provide effective and efficient care for patients by improving access to cardiac catheterization, revascularization, specialist physicians and to new technologies or medications not available at other centers. The regional care model within Southern Alberta consists of one PCI capable center that provides specialized procedural cardiac care to numerous smaller and geographically distant community centers. This model’s process of care involves a well established referral system for cardiac catheterization whereby direct communication between community and subspecialty physicians, delivery of detailed patient information and efficient risk based triage of community ACS patients translates into timely referral for and access to cardiac catheterization.

Geographic disparity in cardiac catheterization and revascularization rates in ACS are well described. A large registry study in Denmark found higher coronary angiography and revascularization rates in ACS patients residing close to an interventional facility compared to those residing at a further distance, with a higher probability of receiving catheterization and revascularization if admitted directly to an interventional center [8]. The Dartmouth Atlas of Cardiovascular Health Care in the United States recognized that rates of cardiac catheterization varied substantially from the national average in many referral regions [20]. Another group of investigators from the United States demonstrated that less than half of patients presenting to community hospitals with ACS were transferred to tertiary hospitals for cardiac catheterization [9]. This geographical variance has also been described in Canada where investigators in the province of Nova Scotia found lower rates of cardiac catheterization for patients residing outside of a metropolitan area [21]. Data from the New Zealand Cardiac Society Audit Group demonstrated that patients with ACS admitted to non-interventional centers were less likely to be referred and had longer time delays to access cardiac catheterization compared to those admitted to interventional centers [22]. In our study we found that despite large geographical barriers of up to 291 Km, patients initially presenting to community hospitals had similar or even greater access to cardiac catheterization compared to those initially presenting to the interventional facility.

Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated better clinical outcomes in NSTEMI patients treated with an early invasive approach (early cardiac catheterization and revascularization as required for moderate to high risk NSTEMI) [22]-[26]. These studies showed a consistent reduction in recurrent ischemia and re-infarction but inconsistencies in the survival benefit. In our study we found better 30-day and 1-year outcomes in patients managed invasively compared to those managed conservatively. Due to the observational nature of this study, selection bias may influence outcomes and partially account for baseline differences in patients chosen for cardiac catheterization. This limits generalization of our findings to different populations. Further evaluation of detailed patient characteristics and comorbidities, patient preferences, the shared decision-making process and potential referral physician selection bias are necessary to explain these findings.

In this study, there were no differences in 30-day or 1-year risk adjusted mortality between patients admitted to interventional and community hospitals, despite the differences noted in cardiac catheterization and revascularization rates. Differences in adherence to acute and long- term, guideline based medical therapies, in addition to numerous other patient care factors not evaluated in this study, could account for these findings. Similar findings were noted in a study evaluating outcomes of NSTEMI patients treated in academic and non-academic centers in the United States. Despite higher utilization of guideline based medications, cardiac catheterization and revascularization in academic centers, there were no differences in 1-year mortality compared to non-academic center patients [27].

Our findings support the development of regional initiatives and processes of care that ensure appropriate access to cardiac catheterization for patients with ACS. Facilitating transfer of patients from hospitals without cardiac catheterization capabilities to regional invasive centers is essential for favorable outcomes in ACS. Such a regional care model successfully exists in Southern Alberta where management practices of non-cardiologists in community centers encompass a strong compliance with evidence-based, regional cardiac catheterization referral guidelines and protocols and an aggressive transfer strategy for invasive investigation is the predominant model of care in community centers. Performance of catheterization within guideline recommended timeframes for all patients is a recognized area for improvement in this regional model. The development of formal repatriation processes of care to ensure availability of catheterization facilities may help to achieve these goals.

This study has limitations. We evaluated cardiac catheterization rates for ACS patients in a Canadian regional model that may differ in structure from other international models; nonetheless, our findings provide insights into important ACS management concepts. Although we demonstrated good clinical outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization we were unable to determine why some patients were not referred for cardiac catheterization or whether the treatment of conservatively managed patients was optimal. Additionally, our registry does not audit against key performance indicators or provide detailed information regarding guideline based medical therapies. Admission to presenting hospitals was not randomly assigned, and consequently our results may be confounded by other unmeasured factors. However, these limitations are balanced by the strength of our evaluation of a large, unselected group of real-world ACS patients.

Conclusion

In this large, contemporary, registry-based study we describe a successful regional care model in which ACS patients first admitted to community hospitals have effective access to cardiac catheterization despite geographic and available services barriers. These findings support the importance of regional initiatives and processes of care that facilitate access to cardiac catheterization for ACS patients.

Authors’ contributions

HC, MG and JH participated in study design, analysis, and manuscript revision. MK, WG and DG participated in study design and manuscript revision. DS participated in analysis and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- APPROACH:

-

Alberta Provincial Program for Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart disease

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass surgery

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- NSTEMI:

-

Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- STEMI:

-

ST elevation myocardial infarction

- UA:

-

Unstable angina

References

Mehta SR, Cannon CP, Fox KA, Wallentin L, Boden WE, Spacek R, Widimsky P, McCullough PA, Hunt D, Braunwald E, Jusuf S: Routine vs. selective invasive strategies in patients with acute coronary syndromes- a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2005, 293: 2908-2917. 10.1001/jama.293.23.2908.

Bhatt DL, Roe MT, Peterson ED, Li Y, Chen AY, Harrington RA, Greenbaum AB, Berger PB, Cannon CP, Cohen DJ, Gibson CM, Saucedo JF, Kleiman NS, Hochman JS, Boden WE, Brindis RG, Peacock WF, Smith SC, Pollack CV, Gibler WB, Ohman EM: Utilization of early invasive management strategies for high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. JAMA. 2004, 292: 2096-2104. 10.1001/jama.292.17.2096.

Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Chavey WE, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS: ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 2007, 116: 803-877. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185752.

Camm J, Gray H, Antoniou S, Cadman J, Crowe E, De belder M, Diaz J, Geldard D, Gulhane L, Henderson R, Jahangiri M, Krause T, Lovibond K, Maxwell G, Morris F, Roebuck A, Sloan N, Turner C, Underwood SR, Whitbread M: Unstable angina and NSTEMI: the early management of unstable angina and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. NICE clinical guideline. 2010

Chew D, Anderson F, Avezum A, Eagle K, Fitzgerald G, Gore J, Dedrick R, Brieger D: Six-month survival benefits associated with clinical guideline recommendations in acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2010, 96: 1201-1206. 10.1136/hrt.2009.184853.

Hamm C, Bassand JP, Agewall S, Bax J, Boersma E, Bueno H, Caso P, Dudek D, Gielen S, Huber K, Ohman M, Petrie M, Sonntag F, Uva MS, Storey R, Wijns W, Zahger D: ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2011, 32: 2999-3054. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236.

Hvelplund A, Galatius S, Madsen M, Rasmussen J, Sørensen R, Fosbøl E, Madsen J, Rasmussen S, Jørgensen E, Thuesen L, Møller C, Abildstrøm S: Influence of distance from home to invasive centre on invasive treatment after acute coronary syndrome:a nationwide study of 24 910 patients. Heart. 2011, 97: 27-32. 10.1136/hrt.2010.203901.

Ferreira-Gonzalez I, Permanyer-Miralda G, Heras M, Cunat J, Civeira E, Aros F, Rodriguez J, Sanchez P, Marsal J, Ribera A, Marrugat J, Bueno H: Patterns of use and effectiveness of early invasive strategy in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: an assessment by propensity score. Am Heart J. 2008, 156: 946-953. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.032.

Roe MT, Chen AY, Delong ER, Boden WE, Calvin JE, Cairns CB, Smith SC, Pollack CV, Brindis RG, Califf RM, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED: Patterns of transfer for patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome from community to tertiary care hospitals. Am Heart J. 2008, 156: 185-192. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.033.

Ghali WA, Knudston ML: Overview of the Alberta provincial project for outcome assessment in coronary heart disease. Can J Cardiol. 2000, 16: 1225-1230.

Faris P, Ghali W, Brant R, Norris C, Galbraith D, Knudtson M: Multiple imputation versus data enhancement for dealing with missing data in observational health care outcomes analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002, 50: 184-191. 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00433-4.

Khot UN, Johnson ML, Ramsey C, Khot MB, Todd R, Shaikh SR, Berg WJ: Emergency department physician activation of the catheterization laboratory and immediate transfer to an immediately available catheterization laboratory reduce door to balloon time in ST elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007, 116: 67-76. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.677401.

LeMay MR, Davies RF, Dionne R, Maloney J, Trickett J, So D, Ha A, Sherrard H, Glover C, Marquis JF, O’Brien ER, Stiell IG, Poirier P, labinaz M: Comparison of early mortality of paramedic diagnosed ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with immediate transport to a designated primary percutaneous coronary intervention center to that of similar patients transported to the nearest hospital. Am J Cardiol. 2006, 98: 1329-1333. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.019.

de Villiers JS, Anderson T, McMeekin JD, Leung RCM, Traboulsi M: Expedited transfer for primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a program evaluation. Can Med Ass J. 2007, 176: 1833-1838. 10.1503/cmaj.060902.

O’Gara P, Kushner F, Ascheim D, Casey D, Chung M, de Lemos J, Ettinger S, Fang J, Fesmire F, Franklin B, Granger C, Krumholz H, Linderbaum J, Morrow D, Newby L, Ornato J, Ou N, Radford M, Tamis-Holland J, Tommaso C, Tracy C, Woo Y, Zhao D: 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-Elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 61: 78-140. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019.

Alberts M, Latchaw R, Selman W, Shephard T, Hadley M, Brass L, Koroshetz W, Marler J, Booss J, Zorowitz R, Croft J, Magnis E, Mulligan D, Jagoda A, O’Connor R, Cawley C, Connors J, Rose-DeRenzy J, Emr M, Warren M, Walker M: Recommendations for comprehensive stroke centers: a consensus statement from the Brain Attack Coalition. Stroke. 2005, 36: 1597-1616. 10.1161/01.STR.0000170622.07210.b4.

Shultis W, Graff R, Chamie C, Hart C, Louangketh P, McNamara M, Okon N, Tirschwell D: Striking rural-ruban disparities observed in acute stroke care capacity and services in the pacific northwest:implications and recommendation. Stroke. 2010, 41: 2278-2282. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.594374.

Gropen T, Magdon-Ismail Z, Day D, Melluzzo S, Schwamm L: Regional implementation of the stroke systems of care model: recommendations of the northeast cerebrovascular consortium. Stroke. 2009, 40: 1793-1802. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531053.

Walters DL, Aroney CN, Chew DP, Bungey L, Coverdale SG, Allan R, Brieger D: Variations in the application of cardiac care in Australia. results from a prospective audit of the treatment of patients presenting with chest pain. Med J Aust. 2008, 188: 218-223.

Wennberg JE: Appendix on the geography of health care in the United States. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care in the United States. Edited by: Birkmeyer JD. 1990, AHA Press, Chicago, 289-296.

Hassan A, Pearce N, Mathers J, Veugelers P, Hirsch G, Cox J: The effect of place of residence on access to invasive cardiac services following acute myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 2009, 25: 207-212. 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70062-5.

Ellis C, Devlin G, Elliot J, Matsis P, Williams M, Gamble G, Hamer A, Richards M, White H: Acute coronary syndrome patients in New Zealand experience significant delays to access cardiac investigation and revascularization treatment especially when admitted to non-interventional centres: results of the second comprehensive national audit of ACS patients. NZ Med J. 2010, 123: 1319.

Wallentin L, Swahn E, Kontny F, Husted S, Lagerqvist B, Ståhle E: Invasive compared with non-invasive treatment in unstable coronary-artery disease: FRISC II prospective randomised multicentre study. Fragmin and fast revascularization during instability in coronary artery disease investigators. Lancet. 1999, 354: 708-715. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07349-3.

Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, Vicari R, Frey MJ, Lakkis N, Neumann FJ, Robertson DH, DeLucca PT, DiBattiste PM, Gibson CM, Braunwald E: Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344: 1879-1887. 10.1056/NEJM200106213442501.

Fox KA, Poole-Wilson PA, Henderson RA, Clayton TC, Chamberlain DA, Shaw TR, Wheatley DJ, Pocock SJ: Interventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002, 360: 743-751. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09894-X.

Puymirat E, Taldir G, Aissaoui N, Lemesle G, Lorgis L, Cuisset T, Bourlard P, Maillier B, Ducrocq G, Ferrieres J, Simon T, Danchin N: Use of invasive strategy in Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction is a major determinant of improved long term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol Int. 2012, 5: 893-902. 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.05.008.

O’Brien E, Subherwal S, Roe MT, Holmes DN, Thomas L, Alexander KP, Wang TY, Peterson ED: Do patients treated at academic hospitals have better longitudinal outcomes after admission for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction?. Am Heart J. 2014, 167: 762-769. 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.01.009.

Funding sources

Dr Knudtson receives partial support from the Libin Trust Fund. Dr Ghali is supported by the Government of Canada Research Chair in Health Services Research program and by a Health Scholar Award from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (Edmonton, Alberta). APPROACH was funded in 1995 by the W Garfield Weston Foundation and has received ongoing support from Merck Frost Canada Inc, Monsanto Canada Inc/Searle, Eli Lilly Canada Inc, Guidant Corporation, Boston Scientific Ltd, Roche Ltd, Johnson &Johnson Inc, Cordis and the Province Wide Services Advisory Committee of Alberta Health and Wellness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Curran, H.J., Hubacek, J., Southern, D. et al. The effect of a regional care model on cardiac catheterization rates in patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. BMC Health Serv Res 14, 550 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0550-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0550-0