Abstract

Background

Burnout is a common issue among medical professionals, and one of the well-studied predisposing factors is the Big Five personality traits. However, no studies have explored the relationships between these traits and burnout from a trait-to-component perspective. To understand the specific connections between each Big Five trait and burnout components, as well as the bridging effects of each trait on burnout, we employed network analysis.

Methods

A cluster sampling method was used to select a total of 420 Chinese medical personnel. The 15-item Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory-15 (CBF-PI-15) assessed the Big Five personality traits, while the 15-item Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) assessed burnout components. Network analysis was used to estimate network structure of Big Five personality traits and burnout components and calculate the bridge expected influence.

Results

The study revealed distinct and clear relationships between the Big Five personality traits and burnout components. For instance, Neuroticism was positively related to Doubt significance and Worthwhile, while Conscientiousness was negatively related to Accomplish all tasks. Among the Big Five traits, Neuroticism displayed the highest positive bridge expected influence, while Conscientiousness displayed the highest negative bridge expected influence.

Conclusions

The network model provides a means to investigate the connections between the Big Five personality traits and burnout components among medical professionals. This study offers new avenues for thought and potential targets for burnout prevention and treatment in medical personnel, which can be further explored and tested in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Burnout is a syndrome referred to as an “occupational phenomenon” despite lacking a single definition [1, 2]. Maslach and Jackson categorized burnout into three components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low feelings of personal accomplishment, which refers to a sense of competence and successful achievement in one’s work [3]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that burnout affects various healthcare professionals [4,5,6], negatively impacting their physical and mental well-being. Adverse effects may include stress-related syndromes or illnesses such as depression, anxiety, perceived memory impairment, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [7]. Medical errors, decreased productivity, early retirement, and a compromised work-life balance are common consequences of these negative impacts [8,9,10]. Given its prevalence and potential detrimental effects, understanding the underlying causes of burnout is crucial.

Personality traits have been found to contribute to the development of burnout [11]. Numerous studies conducted in the past decade have emphasized the importance of psychological factors and identified specific personality traits that either facilitate or act as barriers to the development of burnout [12]. More recently, researchers have utilized the five-factor model of personality traits, commonly known as the “Big Five” to explore the relationship between personality and burnout [13]. The Five Factor Theory, which breaks down personality into five fundamental components, is a widely accepted framework for measuring traits. The “Big Five” personality traits consist of Neuroticism (degree of emotional instability), Extraversion (degree of sociability and liveliness), Agreeableness (degree of interpersonal tendencies to approach or reject others), Conscientiousness (degree of self-control and self-determination), and Openness (degree of intellectual curiosity and aesthetic sensibility) [14].

Most of the reviewed studies indicate that individuals with higher levels of Neuroticism and lower levels of Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness are more prone to burnout [15]. Neuroticism, in particular, may contribute to burnout due to difficulties in managing emotions and impulses. Neurotic individuals commonly experience insecurity, anxiety, anger, and depressive symptoms [16], which hinder their ability to perform job tasks satisfactorily and act as an amplifying “filter” for negative events [17], thereby increasing the risk of burnout [18]. On the other hand, Agreeableness, which enables warm interpersonal interactions, may have a protective effect against burnout, preventing individuals from experiencing depersonalization [19]. While several studies have investigated the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and burnout, the results have been inconsistent. Although most studies have found a strong negative association between Openness and burnout, other studies have reported opposite correlations between Openness and the three dimensions of burnout [20,21,22]. Furthermore, while certain studies have found a positive correlation between burnout and Extraversion, the reasons for this contradictory finding remain unexplained [21]. Given these discrepancies, further clarification of the links between the Big Five personality traits and burnout is necessary.

In previous studies, the correlation between the Big Five personality traits and burnout has often been examined by categorizing burnout as a unitary concept or its three dimensions [23,24,25]. However, this kind of approach may have an influence on overlooking the heterogeneity of burnout and mask the varying correlations between different components and personality traits, leading to inconsistent results. Previous research has demonstrated that burnout could be viewed as an interactive system comprising various components [26, 27]. Recent studies utilizing a network model have identified specific psychological characteristics, such as mental well-being [26] and depression [28], that are specifically associated with individual burnout components. Therefore, adopting a component-based approach may provide a fresh perspective and enhance understanding of the relationships between the Big Five personality traits and burnout.

From the perspective of network, a psychological construct can be seen as a network of components (nodes) and the interactions (edges) between them [29]. Depending on the strength of their direct connections (edge weights), nodes may either reinforce or inhibit each other in a network model incorporating the Big Five personality traits and burnout components. Network analysis offers a direct examination of the relationships between individual components and their predisposing factors, presenting an insightful visualization of these associations that traditional statistical models do not provide [30,31,32]. By examining the network structure, researchers can gain a clear understanding of which Big Five personality traits are closely linked to each of the burnout components. Additionally, network analysis offers new metrics for assessing the potential effects of significant predisposing factors on component communities [33]. For the community of burnout components, the bridge expected influence could specifically measure the extent to which each Big Five personality trait activates or deactivates the community, transmitting positive or negative effects [33]. This knowledge could be crucial in identifying prospective personality targets for burnout prevention and intervention.

The present study utilizes network analysis to compare the Big Five personality traits with burnout at the trait-to-component level. Our objectives are to investigate: (1) the specific connections between the Big Five personality traits and burnout components, and (2) the bridging effects of each Big Five personality trait on the cluster of burnout components by examining the bridge expected influence of each trait. We hypothesize that Neuroticism will activate the community of burnout components, while Conscientiousness will deactivate it.

Methods

Participants

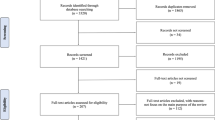

Between April 16 and April 18, 2021, paper and pencil examinations were administered to collect data. The study participants consisted of 458 medical professionals from Xijing Hospital in the Chinese province of Shaanxi. Prior to participation, all participants provided informed consent. The investigation began with the collection of demographic information. 38 participants were excluded from the study for failing two honesty checks or providing incorrect answers to the demographic questions.

Measures

Big five personality traits

The Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory-15 (CBF-PI-15) [34, 35] was used to assess the five dimensions of the Big Five personality traits. Each subscale (Neuroticism, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, Openness, and Extraversion) included three items. Participants were asked to rate their responses on a six-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (“disagree strongly”) to 6 (“agree strongly”). Sample items include “I often feel disturbed (Neuroticism)”, “One of my characteristics is doing things logically and orderly (Conscientiousness)”, “I think most people are well-intentioned (Agreeableness)”, “I’m a person who loves to take risks and break the rules (Openness)”, and “I like to go to social and recreational parties (Extraversion)”. With good reliability and validity (such as convergent, discriminant, and criterion-related validity) [34], the CBF-PI-15 has been widely adopted in previous studies (e.g., [36, 37]). The internal consistency values for each subscale were as follows: Neuroticism (0.83), Conscientiousness (0.75), Agreeableness (0.70), Openness (0.88), and Extraversion (0.70).

Burnout components

The Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) was first developed by American social psychologists Maslach and Jackson and was utilized to measure occupational burnout [38]. Each question is scored on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (very frequently), and the sum of these scores reflects the level of burnout. Li and colleagues found that one item in the cynicism dimension of the MBI-GS showed a significant cross load through exploratory factor analysis. Therefore, they recommended excluding this item for a better version of the MBI-GS (Chinese version) [39]. The Chinese version of the MBI-GS was usually adopted for its localization characteristics, as well as its strong reliability and validity. In the present study, the Chinese version of MBI-GS was adopted to investigate burnout among medical workers. This Chinese translation of the MBI-GS used in this study comprises 15 items divided into three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (items 1–5), depersonalization (items 6–9), and low feelings of personal accomplishment (items 10–15; reverse scoring). With good reliability and validity (such as construct validity) [39], the Chinese version of MBI-GS has been widely used in previous research (e.g., [40, 41]). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the MBI-GS in this study was 0.93.

Network analysis

The target trait-to-component network was estimated through graphical Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator based on Extended Bayesian Information Criterion criterium (hyperparameter gamma = 0.5) [42]. Within the network, edges depict the partial (Spearman) correlation between two nodes after controlling for all other nodes [42, 43]. The Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm [44] and R-package qgraph was used for the network construction and visualization [45].

Bridge expected influence was computed for each node in the target trait-to-component network by R-package networktools [33]. Higher positive/negative bridge expected influence value implies greater ability for activating/deactivating the other communities [33]. The communities were pre-defined: one community is Big Five personality traits (five nodes) and the other community is burnout components (fifteen nodes).

The network robustness test was conducted through R-package bootnet [29]. The accuracy of edge weights was examined by plotting the 95% confidence interval using 1,000 bootstrap samples and calculating bootstrapped difference tests for edge weights. The stability of bridge expected influence was assessed by computing the correlation stability (CS)-coefficient via a case-dropping bootstrap approach using 1,000 bootstrap samples and calculating bootstrapped difference tests for bridge expected influence. The ideal CS-coefficient is above 0.5 and should not be below 0.25 [29].

Results

Descriptive data analysis

The final sample comprised 221 nurses (female = 213) and 199 doctors (female = 130), all aged between 22 and 50 years (mean = 32.74, SD = 5.37). Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants. Table 2 displays the abbreviations, mean scores, standard deviations and bridge expected influence for each variable used in the current network analysis.

Network structure

Figure 1 represents the estimated network, which retained a total of 23 between-community edges (30.67%) with non-zero edge weights (ranging from − 0.13 to 0.15) out of 75 potential between-community edges. Table S1 (in supplementary materials) shows all edges weights within the final network. Among the fifteen burnout components, six exhibited positive correlations with Neuroticism (weights ranging from 0.02 to 0.15). The strongest edge existed between Neuroticism and Doubt significance (B8; edge weight = 0.152). The second-strongest edge connected Neuroticism and Worthwhile (B14; edge weight = 0.150). Conscientiousness demonstrated connections with five burnout components (out of 15), with four negative edges and one positive edge (weights ranged from − 0.13 to 0.02). The burnout component Accomplish all tasks (B15; edge weight = -0.13) exhibited the strongest negative relationship with Conscientiousness. The second strongest negative edge connected Conscientiousness and Worthwhile (B14; edge weight = -0.11). Among the fifteen burnout components, five showed negative correlations with Agreeableness (weights ranging from − 0.05 to -0.004). Two burnout components (out of 15) demonstrated negative links with Openness, with edge weights of -0.05 and − 0.01, respectively. Similarly, five burnout components (out of 15) were negatively associated with Extraversion, with weights ranging from − 0.08 to -0.01. The edge between Extraversion and Tired exhibited the strongest negative correlation (B3; edge weight = -0.084). The second-strongest negative edge connected Extraversion and Happy (B13; edge weight = -0.076). Figure S1 (Supplementary Material) showed the bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals for edge weights. The bootstrapped difference test for edge weights was displayed in Figure S2 (Supplementary Material).

Network structure of Big Five personality traits and burnout. Blue edges represent positive connections, red edges represent negative connections. A total description of nodes of Big Five personality traits and burnout components could be seen in Table 2

Table 2; Fig. 2 illustrate the raw bridge expected influence values. Neuroticism exhibited the highest positive bridge expected influence among all nodes (value = 0.51), while Conscientiousness showed the highest negative bridge expected influence (value = -0.27). Figure S3 (in Supplementary Material) demonstrated the adequate stability of the bridge expected influence, with a CS-coefficient value of 0.75 exceeding 0.50. The bootstrapped difference test (Figure S4 in the Supplementary Material) revealed differences in the bridge expected influence among nodes.

Bridge expected influence plot. A total description of nodes of Big Five personality traits and burnout components could be seen in Table 2

Discussion

The present study is the first to utilize a trait-to-component network approach to explore the connections between the Big Five personality traits and burnout components. In line with our initial objective, we uncovered several distinct between-community connections, both positive and negative, such as Neuroticism-Doubt significance (B8), Conscientiousness-Accomplish all tasks (B15), and Extraversion-Tired (B3). The strongest positive association was observed between Neuroticism and Doubt significance (B8). Our second objective and study hypotheses were supported by the results of bridge expected influence, which revealed that Conscientiousness and Extraversion deactivate the burnout components community while Neuroticism activates it. We also demonstrated that Agreeableness and Openness may deactivate the burnout components community.

The strongest positive edges between communities were observed between Neuroticism and Doubt significance (B8), while the second-strongest edges were found between Neuroticism and Worthwhile (B14). These two edges illustrate the association between Neuroticism and depersonalization, as well as low emotions of personal accomplishment. Neuroticism, characterized by worry, insecurity, depression, fear, and apprehension [16, 46, 47], often leads individuals to employ avoidance and diversion as coping mechanisms [48]. In demanding and highly competitive careers, such behavior is likely to result in higher levels of depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment [49, 50]. This finding is consistent with previous research on burnout among medical professionals [50,51,52]. Most connections between Conscientiousness and burnout, such as those between Conscientiousness and Accomplish all tasks (B15) and Worthwhile (B14), were found to be negative. Conscientious individuals, known for their ability to manage and organize their work and time, are adept at employing efficient coping mechanisms that keep their focus on problem-solving in stressful situations [14]. This argument aligns with earlier research suggesting that Conscientiousness facilitates individuals’ perception of professional efficacy [53]. We also discovered an intriguing positive link between Conscientiousness and Indifferent (B9). This relationship may be attributed to the occupational peculiarities of medical staff; under increased pressure resulting from deteriorating doctor-patient relationships, medical staff may view it as their duty to provide for patients while avoiding excessive emotional involvement. Nevertheless, further investigations are needed to provide a more detailed explanation for this finding. Furthermore, the final network structure revealed that the majority of components in the burnout community were positively connected. Three edges with the highest weights within the burnout community were Emotionally drained-Used up (B1-B2), Contributing-Good at job (B11-B12), and Worthwhile-Accomplish all tasks (B14-B15). These results about strongest edges were similar to our previous studies on the network structure of burnout among medical staff and Chinese nurses [26, 27].

The bridge centrality of nodes may shed light on the specific roles played by each of the Big Five personality traits in the context of burnout [54, 55]. Nodes with higher bridge expected influence values are more likely to activate the burnout components community. Thus, from the perspective of the Big Five personality traits, this provides empirical evidence for early detection and intervention of medical staff burnout. Specifically, Neuroticism exhibits a high positive bridge expected influence value, suggesting that it effectively activates the burnout component community. This finding is consistent with a previous study that utilized network analysis to examine the bridging effects of each Big Five personality trait on the symptom community of problematic smartphone use and found that Neuroticism had the highest positive bridge centrality [56]. Individuals with high levels of Neuroticism often experience heightened levels of stress, tend to magnify the seriousness of threats, and underestimate their own capabilities. On the other hand, Conscientiousness exhibits the highest negative value of bridge expected influence, indicating its potential to effectively deactivate the burnout components community. Bridge nodes have been identified as crucial intervention targets since addressing them could modify the co-occurring phenomenon of communities [33]. Therefore, addressing medical staff burnout may involve reducing Neuroticism and enhancing Conscientiousness.

Limitations

Although the present study employs a novel component-based approach, namely network analysis, to explore the connections between the Big Five personality traits and burnout components among medical staff, there are several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the theoretical foundation of this study assumes that personality characteristics can impact burnout, and the findings were interpreted in light of the potential predictive pathways between personality traits and burnout. However, due to the cross-sectional design employed in this study, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the Big Five personality traits may have changed as a consequence of experiencing burnout symptoms. Secondly, if alternative measurement scales are utilized for assessing the components, it is uncertain whether the network structure established in this study, based on the questionnaires employed, can be replicated. Moreover, since the instrument employed relies on self-reporting, response bias is inevitable, although future research could incorporate additional objective measurement techniques. Finally, the current study’s sample size selection was informed by the work of Epskamp et al. (2018), which suggest a minimum sample size of 210 for a 20-node network analysis [29]. Additionally, we calculated the CS-coefficient, adhering to recommended best practices for ensuring network stability. It’s important to note that while the CS-coefficient is optimal for this study, its determination was post hoc rather than a priori. Since our data collection, newer methodologies for a priori sample size estimation have emerged. Specifically, the method proposed by Constantin and colleagues indicates that a sample size of 3582 could achieve a sensitivity of 0.6 in 80% of cases [57]. This larger sample size is recommended for future studies aiming to replicate our findings.

Conclusions

Future research should prioritize elucidating the potential significance of personality traits, encouraging early detection of at-risk people, and developing successful therapies [58]. The onset and progression of burnout are significantly influenced by personality factors [59]. Our investigation of the Big Five personality traits and burnout components among medical staff from a trait-to-component viewpoint is the first, as far as we are aware. Despite the aforementioned restrictions, this research has significant theoretical and clinical implications. On the one hand, we investigate the relationships between the Big Five personality traits and burnout’s components, which may enhance the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and burnout’s potential theoretical mechanism and offer a fine-grained understanding of how medical staff with various personalities influence various burnout’s components (potential pathways). However, when it comes to addressing the needs of lowering burnout in medical personnel, the findings on Neuroticism (with the highest positive bridge expected influence) and Conscientiousness (with the highest negative bridge expected influence) may have significant consequences.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Schaufeli W. The burnout enigma solved? Scandinavian journal of work. Environ Health. 2021;47(3):169–70. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3950.

WHO. Burn-out an Occupational Phenomenon: international classification of diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organizational Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205.

Khan A, Teoh KR, Islam S, et al. Psychosocial work characteristics, burnout, psychological morbidity symptoms and early retirement intentions: a cross-sectional study of NHS consultants in the UK. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e018720. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018720.

Vijendren A, Yung M, Shiralkar U. Are ENT surgeons in the UK at risk of stress, psychological morbidities and burnout? A national questionnaire survey. The Surgeon. 2018;16(1):12–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2016.01.002.

Imo UO. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):197–204. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.116.054247.

Peterson U, Demerouti E, Bergström G, et al. Burnout and physical and mental health among Swedish healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):84–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04580.x.

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, et al. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-325.

Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI et al. Physician Burnout, Well-being, and Work Unit Safety Grades in Relationship to Reported Medical Errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(11):1571-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014.

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with Work-Life Integration in Physicians and the General US Working Population between 2011 and 2020. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(3):491–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.021.

Narang G, Wymer K, Mi L, et al. Personality traits and burnout: a Survey of practicing US urologists. Urology. 2022;167:43–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2022.03.004.

Narumoto J, Nakamura K, Kitabayashi Y, et al. Relationships among burnout, coping style and personality: study of Japanese professional caregivers for elderly. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62(2):174–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01751.x.

McCrae RR, Costa PT. Discriminant validity of NEO-PIR facet scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1992;52(1):229–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316449205200128.

Costa PT, Mccrae RR, Revised. NEO personality inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI). New York: Springer; 1992.

Angelini G. Big five model personality traits and job burnout: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01056-y.

Digman JM. Personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model. Ann Rev Psychol. 1990;41:417–40. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163655.

Semmer NK. Personality, stress, and coping. Handbook of personality and health. edn. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2006. pp. 73–113.

Bianchi R, Manzano-García G, Rolland JP. Is burnout primarily linked to work-situated factors? A relative Weight Analytic Study. 2021;11:623912. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.623912.

Zimmerman RD. Understanding the impact of personality traits on individuals’ turnover decisions: a meta-analytic path model. Pers Psychol. 2010;61(2):309–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00115.x.

Castillo Gualda R, Herrero M, Carvajal R, et al. The role of emotional regulation ability, personality, and Burnout among Spanish teachers. Int J Stress Manage. 2019;226. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000098.

Armon G, Shirom A, Melamed S. The big five personality factors as predictors of changes across time in burnout and its facets. J Pers. 2012;80(2):403–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00731.x.

Bahadori M, Ravangard R, Raadabadi M, et al. Job stress and job burnout based on personality traits among Emergency Medical technicians. Trauma Monthly. 2019;24:24–31. https://doi.org/10.30491/TM.2019.104270.

Vaulerin J, Colson SS, Emile M, et al. The big five personality traits and French Firefighter Burnout: the mediating role of achievement goals. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(4):e128–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000679.

Piotrowski K, Bojanowska A, Szczygieł D, et al. Parental burnout at different stages of parenthood: links with temperament, big five traits, and parental identity. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1087977. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1087977.

Sekułowicz M, Kwiatkowski P, Manor-Binyamini I, et al. The effect of personality, disability, and Family Functioning on Burnout among mothers of children with autism: a path analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031187.

Chen C, Li F, Liu C, et al. The relations between mental well-being and burnout in medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: a network analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:919692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.919692.

Wu L, Ren L, Wang Y, et al. The item network and domain network of burnout in Chinese nurses. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00670-8.

He M, Li K, Tan X, et al. Association of burnout with depression in pharmacists: a network analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1145606. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1145606.

Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50(1):195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1.

Fried EI, Cramer AOJ. Moving Forward: challenges and directions for Psychopathological Network Theory and Methodology. Perspectives on psychological science. J Association Psychol Sci. 2017;12(6):999–1020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617705892.

Wei X, Jiang H, Wang H, et al. The relationship between components of neuroticism and problematic smartphone use in adolescents: a network analysis. Pers Indiv Differ. 2022;186:111325–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111325.

Liang S, Liu C, Rotaru K, et al. The relations between emotion regulation, depression and anxiety among medical staff during the late stage of COVID-19 pandemic: a network analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114863.

Jones PJ, Ma R, McNally RJ. Bridge Centrality: A Network Approach to Understanding Comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2021 Mar-Apr;56(2):353– 67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898.

Zhang X, Wang MC, He L, et al. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese big five personality Inventory-15. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0221621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221621.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

Zhao H, Shi H, Ren Z, et al. The Mediating Role of Extra-family Social Relationship between personality and depressive symptoms among Chinese adults. Int J Public Health. 2022;67:1604797. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604797.

Zhao H, Shi H, Ren Z, et al. Gender and age differences in the associations between personality traits and depressive symptoms among Chinese adults: based on China Family Panel Study. Health & social care in the community. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(6):e5482–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13972.

Zhang XJ, Song Y, Jiang T, et al. Interventions to reduce burnout of physicians and nurses: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Medicine. 2020;99(26):e20992. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000020992.

Li CP, Shi K. The influence of distributive justice and procedural justice on job burnout. Acta Physiol Sinica. 2003;35(5):677–84. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022289509702.

Yin H, Jiang C, Shi X, et al. Job burnout is Associated with Prehospital decision Delay: an internet-based survey in China. Front Psychol. 2022;13:762406. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.762406.

Xu W, Pan Z, Li Z, et al. Job Burnout among Primary Healthcare workers in Rural China: a Multilevel Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030727.

Epskamp S, Fried EI. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol Methods. 2018;23(4):617–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167.

Isvoranu AM, Epskamp S. Which estimation method to choose in network psychometrics? Deriving guidelines for applied researchers. Psychol Methods. 2023;28(4):925–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000439.

Fruchterman TMJ, Reingold EM. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw Pract Experience. 2010;21(11):1129–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/spe.4380211102.

Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, et al. Qgraph: network visualizations of relationships in Psychometric Data. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(4):1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/JSS.V048.I04.

Saucier G, Ostendorf F. Hierarchical subcomponents of the big five personality factors: a cross-language replication. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(4):613–27. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.613.

Bakker AB, Van der Zee KI, Lewig KA, et al. The relationship between the big five personality factors and burnout: a study among volunteer counselors. J Soc Psychol. 2006;146(1):31–50. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.1.31-50.

Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Vargas C, San Luis C, et al. Risk factors and prevalence of burnout syndrome in the nursing profession. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):240–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111432.

Brown PA, Slater M, Lofters A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: an international study. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2019;12:169–77. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S195633.

De la Fuente-Solana EI, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Cañadas GR, et al. Burnout and its relationship with personality factors in oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nursing: Official J Eur Oncol Nurs Soc. 2017;30:91–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2017.08.004.

Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Velando-Soriano A, Pradas-Hernandez L, et al. Prevalence, levels and related factors of burnout in nurse managers: a multi-centre cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(4):954–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13575.

David IC, Quintão S. Burnout in teachers: its relationship with personality, coping strategies and life satisfaction. Acta Medica Portuguesa. 2012 May-Jun;25(3):145–55.

Bekesiene S. Impact of personality on cadet academic and military performance within mediating role of self-efficacy. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1266236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1266236.

Liu C, Ren L, Li K, et al. Understanding the Association between Intolerance of Uncertainty and problematic smartphone use: A Network Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:917833. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.917833.

McNally RJ. Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behav Res Ther. 2016;86:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.006.

Liu C, Ren L, Rotaru K, et al. Bridging the links between big five personality traits and problematic smartphone use: a network analysis. J Behav Addict. 2023;12(1):128–36. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00093.

Constantin MA, Schuurman NK, Vermunt JK. A general Monte Carlo method for sample size analysis in the context of network models. Psychol Methods. 2023 Jul;10. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000555. Epub ahead of print.

Fineberg NA, Demetrovics Z, Stein DJ, et al. Manifesto for a European research network into problematic usage of the internet. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(11):1232–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.004.

Alarcon G, Eschleman KJ, Bowling NA. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: a meta-analysis. Work Stress. 2009;23(3):244–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370903282600.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants who took part in the study, as well as the hospital staff and physicians who assisted with the recruitment process.

Funding

The Key Project of Air Force Equipment Comprehensive Research (KJ2022A000415), the Development Mechanism and Adustment Strategy of Nursing Staff Burnout in the post-epidemic Era (2023KXKT018), and Research on the characteristics of attention network based on multi-modal indicators (2023KXKT061) provided funding for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The initial draft of the publication was prepared by WYF and RL. RL, WL, WC and WM collected all the data and prepared all the figures. FTW and WQY revised the grammar and expression of the article. RL and LXF reviewed the manuscript. LC and LKL provided effective guidance during the paper revision process.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Fourth Military Medical University’s First Affiliated Hospital’s Ethics Committee approved the data collection process, which was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Project No. KY20202063-F-2). Prior to participation, all participants provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors of this study declare that they have no financial or commercial interests that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wu, L., Liu, C. et al. A network analysis bridging the gap between the big five personality traits and burnout among medical staff. BMC Nurs 23, 92 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01751-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01751-0