Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 epidemic in China, clinical nurses are at an elevated risk of suffering fatigue. This research sought to investigate the correlation between dispositional mindfulness and fatigue among nurses, as well as the potential mediation role of sleep quality in this relationship.

Methods

This online cross-sectional survey was performed from August to September 2022 to collect data from 2143 Chinese nurses after the re-emergence of COVID-19. The significance of the mediation effect was determined through a bootstrap approach with SPSS PROCESS macro.

Results

Higher levels of dispositional mindfulness were significantly negatively related to fatigue (r = -0.518, P < 0.001) and sleep disturbance (r = -0.344, P < 0.001). Besides, insufficient sleep was associated with fatigue (r = 0.547, P < 0.001). Analyses of mediation revealed that sleep quality mediated the correlation of dispositional mindfulness to fatigue (β = -0.137, 95% Confidence Interval = [-0.156, -0.120]).

Conclusions

In the post-COVID-19 pandemic era, Chinese nurses’ dispositional awareness was related to the reduction of fatigue, which was mediated by sleep quality. Intervention strategies and measures should be adapted to improve dispositional mindfulness and sleep quality to reduce fatigue in nurses during the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic enters its third year, and with the effective prevention and control of the epidemic, China is currently in the stage of normalized epidemic prevention. Although the psychological state of the public is gradually recovering, there are still some sporadic outbreaks that would cause more serious psychological problems [1]. Faced with the re-emergence of the epidemic, stressful working environments, and extra epidemic prevention work, medical staff still suffer from physical fatigue and psychological burden [2]. Thus, it is essential to focus on the potential physical and psychological issues arising from COVID-19, which could offer valuable insights for effective intervention and prevention strategies.

As the largest workforce within healthcare systems, nurses are essential in the fight against the COVID-19 epidemic [3]. Confronted with unprecedented challenges brought about by the pandemic, such as overwhelming workload, extreme stress, severe lack of sleep quality, and risk of infection, nurses are experiencing both physical and mental distress [4,5,6,7]. Fatigue is described as a subjective sensation of being tired or lacking energy, including both physical and mental fatigue. Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of moderate-to-high fatigue levels ranged from 35.06 to 72.2% during the COVID-19 pandemic [4, 8]. Nurses’ fatigue could cause various physical symptoms and negative emotions, further affecting their health and work performance [9]. Thus, the fatigue of nurses is worthy of attention during this particular period, and it is critical to relieve nurses’ fatigue to improve healthcare quality.

Mindfulness refers to the awareness that arises when individuals focus attention on the present purposefully and without judgment [10]. Not only described as a construct that can be induced via practice but mindfulness has also been conceptualized as a state or as a trait, playing a significant role in fatigue [11,12,13,14]. A plethora of previous research has shown that mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) could promote psychological health, and alleviate suffering from fatigue [15, 16]. Mindfulness has been considered a protective factor against the unprecedented psychological impact caused by the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. Individuals’ psychological states were shown to be less negatively impacted by COVID-19 when they had higher levels of dispositional mindfulness [18]. Additionally, a previous study has revealed an association between mindfulness and the quality of professional life for nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak [19]. However, there are few studies examining whether mindfulness (dispositional mindfulness) could be a protective factor against fatigue among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the relationship between mindfulness (dispositional mindfulness) and the occurrence of fatigue among nurses during the epidemic.

In addition, a correlation between mindfulness and the quality of nurses’ sleep has been reported [20]. During the post-epidemic of the anti-COVID-19 era, the overall prevalence of sleep disturbances was 44.0% in clinical nurses, which would cause various adverse outcomes, including higher mental workload, and more fatigue [6, 7, 21]. According to a previous study, nurses in the COVID-19 care units could benefit from the implementation of the mindfulness-based stress reduction program in enhancing their sleep [22]. However, little is known about the role of sleep quality in the relationship between mindfulness and fatigue among clinical registered nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. We speculated that sleep quality may be a possible pathway for mindfulness to impact the fatigue of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The primary purpose of this research was to investigate the association between mindfulness and fatigue among nurses during COVID-19, with sleep quality serving as a mediator. Our results might help develop better intervention programs to relieve fatigue and improve the sleeping habits of nurses. Two hypotheses were proposed: [1] Mindfulness would have a significant direct effect on fatigue [2]. Sleep quality would play a mediating effect between mindfulness and fatigue.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

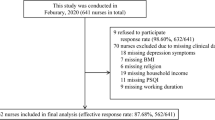

This web-based cross-sectional study was implemented from August 2022 to September 2022 corresponding to the period after COVID-19 flared up again in Jinhua, Zhejiang Province. Nurses from 11 hospitals in Jinhua voluntarily answered the self-administered Chinese anonymous questionnaires via an online platform (www.wjx.com).

Measures

Participant demographics included age, gender, marital status, education, professional title, and years of nursing experience, while fatigue, mindfulness, and sleep quality were evaluated through the Chinese versions of validated psychometric tools.

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) contains 15 items, which are answered on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“almost always”) to 6 (“almost never”). MAAS was used to assess dispositional mindfulness [23], with items such as “I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until sometime later”. Higher total scores of MAAS indicate a greater propensity for daily mindfulness. The Chinese version of MAAS has possessed robust psychometric properties and is widely utilized in practice [20, 24, 25]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this study was 0.929.

The level of fatigue was measured by the 14-item Fatigue Scale (FS-14) [26], with a total score ranging from 0 to 14. The higher score signifies more severe fatigue. In addition, items 1–8 of this scale could represent physical fatigue, while items 9–14 could represent mental fatigue. Previous studies demonstrated that the Chinese version of FS-14 was applicable to Chinese people [27, 28]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency of the scale was 0.840.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) measures sleep quality and sleep disturbances over the past month [29]. It consists of 19 self-assessed items classified into seven components: habitual efficiency, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep disturbances, daytime dysfunction, subjective sleep quality, and use of sleep medication. Total scores were weighted from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating increasingly poor sleep quality. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the PSQI was 0.790.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed on demographic characteristics, reporting the means and standard deviations of continuous variables as well as the frequency and percentage of categorized data, while the correlation analyses of mindfulness, sleep quality, and fatigue were also calculated. The internal consistency of the scale was determined by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. As for data validity, we examined the common method bias by the Harman single-factor test [30].

The mediation model was tested through the PROCESS macro version 4.1 (www.processmacro.org/index.html) (Model 4) [31]. For the best test of the mediation effect, the bootstrapping procedure (5,000 resamples) to measure the indirect effect was carried out, with the significant mediating (indirect) effect established by a 95% confidence interval (CI) excluding zero. The mediation analysis was also controlled for age, gender, and education level. All the research data were analyzed by the IBM SPSS statistics 23.0. Two-tailed p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Common method bias testing

Since the study data were gathered through self-report questionnaires, which might result in common method deviations, the Harman single-factor analysis was performed to screen for the common method bias. There was no serious common method bias in this investigation, as the results showed 6 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the interpretation rate of the first factor was 29.589% (less than the 40% critical standard).

Demographic characteristics and preliminary correlation analyses

The questionnaire was effectively completed by 2143 nurses, as shown in Table 1. Of the total sample, 2075 females (96.80%) were female, 1059 (49.40%) were married, 1343 (62.67%) had a college degree or above, and 1031 (48.10%) obtained a junior technical title. Participants were 30.15 years old on average (SD = 7.70) and had 9.17 years of nursing experience on average (SD = 8.36).

The Pearson correlations for key variables were represented in Table 2. Sleep quality (r = -0.344, P < 0.001) and fatigue (r = -0.518, P < 0.001) were significantly negatively correlated with mindfulness. There was also a significant relationship between fatigue and sleep disturbance (r = 0.547, P < 0.001). Additionally, a significant association was also found between mindfulness and different perspectives of fatigue (physical fatigue: r = -0.448, P < 0.001; mental fatigue: r = -0.469, P < 0.001).

Mediating effect analysis

Following the preliminary results and correlations, sleep quality was examined as a potential mediator of mindfulness-fatigue associations through Model 4 in PROCESS. Age, gender, and education level were set as covariates. As shown in Table 3, mindfulness had a significant effect on nurses’ fatigue (β = -0.512, p-value < 0.001) and sleep quality (β = -0.340, p-value < 0.001). The direct effect was also statistically significant (β = -0.374, p-value < 0.001). By checking the bootstrapped 95% confidence interval, the significant indirect effect of sleep quality was identified in Table 4. This indicated that sleep quality mediated the relationship between mindfulness and fatigue. The mediation effect of sleep quality was also observed when fatigue was divided into two aspects (all p-values < 0.001) (Tables 3 and 4). Figure 1 illustrated the mediation model of dispositional mindfulness, sleep quality, and fatigue (including different perspectives of fatigue), along with standardized path coefficients. Besides, considering the cross-sectional design of this study and a possible bidirectional relationship between mindfulness and sleep quality, the reversed mediation model with mindfulness as a mediator was also analyzed, and the results were also significant (β = 0.129, bootstrap CI = 0.109,0.150).

Relational model of dispositional mindfulness, sleep quality and fatigue (including different perspectives of fatigue). Note: (A) The model of sleep quality mediates the association between dispositional mindfulness and fatigue; (B) The model of sleep quality mediates the association between dispositional mindfulness and physical fatigue; (C) The model of sleep quality mediates the association between dispositional mindfulness and mental fatigue; c: total effect; c’: direct effect; β: standardized coefficient; *P < 0.001

Discussion

The present study intensively investigated the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and fatigue in a large sample of 2134 Chinese nurses. Our findings revealed that mindfulness was considerably and inversely related to fatigue among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. When sleep quality was included, it mediated the association. Despite the high incidence of fatigue among nurses and the apparent impact of mindfulness-based interventions on fatigue, to our knowledge, this was the first study to explore the association between dispositional mindfulness and fatigue in nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to this analysis, mindfulness was negatively associated with nurses’ fatigue. The conclusion was in line with some studies that revealed that mindfulness was a protective factor against fatigue [12,13,14], and we further discussed that sleep quality could act on the mindfulness-fatigue connection. Mindfulness is the capacity to stay in the present moment and accept one’s experiences and emotions, which is related to enhanced psychological functioning and tolerance for unpleasant emotions and situations [32]. One of the previous studies has found that dispositional mindfulness could lessen fatigue through its effects on emotion regulation among nurses [13]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, higher levels of dispositional mindfulness could facilitate nonjudgmental awareness to increase the acceptance of COVID-19-related stressors, moderating the symptoms of anxiety and depression [17]. Thus, the higher the level of mindfulness in nurses, the less likely they would engage in fatigue when facing a stressful environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, this study also found the associations between mindfulness and different aspects of fatigue including physical and mental fatigue. This finding was interesting and further confirmed that there was a close relationship among mindfulness, body sensation, and mental health. Specifically, previous studies have demonstrated that mindfulness could alleviate the sense of physical fatigue by enhancing body awareness, reducing bodily tension, and improving self-regulation [23]. Besides, individuals with higher levels of mindfulness tend to demonstrate stronger emotional regulation, cognitive flexibility, and more positive mental health conditions, which may explain why they were less likely to be faced with mental fatigue [23]. These findings may provide more evidence of the effectiveness of mindfulness intervention in fatigue, and guide nursing managers to adopt strategies such as encouraging nurses to engage in short mindfulness meditation training [33], providing mindfulness-based mobile applications or online mindfulness-based programs [34, 35], or building a supportive community [36] to increase mindfulness levels of nurses during the epidemic period.

Consistent with prior research, our current results offered support for the correlation between fatigue and sleep quality in nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak [7, 37]. Heavy workloads and exposure to extreme stress limited nurses’ opportunity to adequately sleep after work hours, attributing to their feelings of fatigue and daytime dysfunction [6, 38]. In addition, the re-emergence of the epidemic would lead to the disruption of the recovered life, causing a negative psychological impact such as insomnia, anxiety, and depression on nurses, which would significantly influence their physical and mental fatigue [37,38,39]. Therefore, sleep quality-oriented intervention strategies and measures should be improved to effectively relieve fatigue among this population.

In addition, there was an association between mindfulness disposition and sleep quality among nurses. Previous studies have proved that mindfulness could protect nurses from sleep disturbance [20, 40]. Due to the beneficial impact of mindfulness in reducing stress-reactivity and increasing emotional balance, nurses with high mindfulness may appear more likely to stay with psychological equanimity in stressful contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic, which could be beneficial for sleep-related functioning [20]. Furthermore, it also has been demonstrated that the mindfulness-based stress reduction program could effectively enhance the sleep quality of nurses [22]. Further studies are still needed with more cases to explore the potential mechanisms of mindfulness on sleep quality and verify the validity of mindfulness-based interventions on nurses.

As this analysis was based on cross-sectional data, the results also indicated that the relationship between mindfulness and sleep quality could be reversed. This possible inverse hypothesis was also supported by another path analysis, which was similar to the previous study that nurses with satisfactory and sufficient sleep could predict next-day greater mindful attention [41]. A previous study has also mentioned that improved sleep quality may at times boost mindfulness [42]. Sleep may have an impact on individuals’ self-awareness and consciousness, circadian rhythms, brain function, and neurological health, which might influence the development of mindfulness [43, 44]. Thus, mindfulness also can be seen as a buffer with respect to the association between sleep quality and fatigue. Interventions and strategies such as encouragement of physical activity, cognitive behavioral therapy, provision of sleep education programs, and improvement of working and sleeping environment should also be considered for improving sleep quality in clinical nurses [45,46,47]. Future research that examines the relationship between sleep and mindfulness longitudinally might clarify the nature of their relationship. Nevertheless, the significant role of sleep quality and mindfulness in the fatigue of nurses should be recognized in any situation.

Some limitations of this study should be considered. First, the causality between variables could not be concluded in the current study due to the cross-sectional design. Besides, the dynamic psychological status of nurses could not be precisely reflected in the present study. A longitudinal follow-up study is still needed in the future. Second, the study did not distinguish whether the symptom was pre-existing or new due to the COVID-19 pandemic since the status of nurses before the outbreak was not evaluated, which might be a confounding factor. Third, the clinical nurses enrolled in this study were from partial areas of Jinhua, limiting the generalization of the findings. Fourth, the present research relied entirely on self-reporting, which would lead to bias and compromise the accuracy of the data, limiting the comprehensiveness of the current findings. Furthermore, the questionnaires used in this study were relatively simple. Further evaluation of patients’ anxiety, depression, and insomnia symptoms will be of high value. Fifth, we did not collect the data before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it difficult for us to explore the distinction and how the distinction between during and not during the COVID-19 pandemic may impact the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and fatigue. Future studies were greatly needed to further explore this issue.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results identified dispositional mindfulness as a protective factor against the fatigue of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic and revealed the role of sleep quality in mediating the association between mindfulness and fatigue. It is suggested that managers and nursing policymakers could provide and implement appropriate solutions to increase nurses’ mindfulness to directly or indirectly relieve their fatigue.

Data Availability

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li S, Guo B, Lu X, Yang Q, Zhu H, Ji Y, et al. Investigation of Mental Health Literacy and status of residents during the Re-outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:895553.

Wu Q, Li D, Yan M, Li Y. Mental health status of medical staff in Xinjiang Province of China based on the normalisation of COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022;74.

Fernandez R, Lord H, Halcomb E, Moxham L, Middleton R, Alananzeh I et al. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. 2020;111:103637.

Labrague LJ. Pandemic fatigue and clinical nurses’ mental health, sleep quality and job contentment during the covid-19 pandemic: the mediating role of resilience. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(7):1992–2001.

Sikaras C, Ilias I, Tselebis A, Pachi A, Zyga S, Tsironi M, et al. Nursing staff fatigue and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. AIMS Public Health. 2021;9(1):94–105.

Sagherian K, Cho H, Steege LM. The insomnia, fatigue, and psychological well-being of hospital nurses 18 months after the COVID-19 pandemic began: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2022.

Liu Y, Xian JS, Wang R, Ma K, Li F, Wang FL, et al. Factoring and correlation in sleep, fatigue and mental workload of clinical first-line nurses in the post-pandemic era of COVID-19: a multi-center cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:963419.

Zhan Y-x, Zhao S-y, Yuan J, Liu H, Liu Y-f, Gui L-l et al. Prevalence and influencing factors on fatigue of first-line nurses combating with COVID-19 in China: a descriptive cross-sectional study. 2020;40(4):625–35.

Wang D, Xie X, Tian H, Wu T, Liu C, Huang K, et al. Mental fatigue and negative emotion among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(11):8123–31.

Kabat-Zinn J, Hanh TN. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and Illness. Delta; 2009.

Bodhi B. What does mindfulness really mean? A canonical perspective. Mindfulness: Routledge; 2013. pp. 19–39.

Whitaker RC, Herman AN, Dearth-Wesley T, Hubbell K, Huff R, Heneghan LJ, et al. The association of fatigue with dispositional mindfulness: relationships by levels of depressive symptoms, sleep quality, childhood adversity, and chronic medical conditions. Prev Med. 2019;129:105873.

Heshmati R, Caltabiano MLJEJON. Pathway linking dispositional mindfulness to fatigue in oncology female nurses: exploring the mediating role of emotional suppression. 2020;48:101831.

Pagnini F, Cavalera C, Rovaris M, Mendozzi L, Molinari E, Phillips D, et al. Longitudinal associations between mindfulness and well-being in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2019;19(1):22–30.

Ngo TL. [Review of the effects of mindfulness meditation on mental and physical health and its mechanisms of action]. Sante Ment Que. 2013;38(2):19–34.

Cao S, Geok SK, Roslan S, Qian S, Sun H, Lam SK, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for the recovery of Mental fatigue. Syst Rev. 2022;19(13):7825.

Dailey SF, Parker MM, Campbell A. Social connectedness, mindfulness, and coping as protective factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Couns Dev. 2022.

Wen X, Rafaï I, Duchêne S, Willinger MJIJER, Health P. Did Mindful people do better during the COVID-19 pandemic? Mindfulness is Associated with Well-Being and Compliance with prophylactic measures. 2022;19(9):5051.

Zakeri MA, Ghaedi-Heidari F, Khaloobagheri E, Hossini Rafsanjanipoor SM, Ganjeh H, Pakdaman H, et al. The Relationship between Nurse’s Professional Quality of Life, Mindfulness, and hardiness: a cross-sectional study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychol. 2022;13:866038.

Fang Y, Kang X, Feng X, Zhao D, Song D, Li P. Conditional effects of mindfulness on sleep quality among clinical nurses: the moderating roles of extraversion and neuroticism. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(4):481–92.

Marvaldi M, Mallet J, Dubertret C, Moro MR, Guessoum SBJN, Reviews B. Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2021;126:252–64.

Nourian M, Nikfarid L, Khavari AM, Barati M, Allahgholipour ARJHNP. The impact of an online mindfulness-based stress reduction program on sleep quality of nurses working in COVID-19 care units: a clinical trial. 2021;35(5):257–63.

Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48.

Chen S, Cui H, Zhou R, Jia Y-YJCJCP. Revision of Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). 2012;20(2):148–51.

Wu Y, Wei Y, Li Y, Pang J, Su Y. Burnout, negative emotions, and wellbeing among social workers in China after community lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediating roles of trait mindfulness. 2022;10.

Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37(2):147–53.

Wong WS, Fielding R. Construct validity of the Chinese version of the chalder fatigue scale in a Chinese community sample. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68(1):89–93.

Liu L, Xu P, Zhou K, Xue J, Wu H. Mediating role of emotional labor in the association between emotional intelligence and fatigue among Chinese doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):881.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903.

Hayes AF, Montoya AK, Rockwood NJ. The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Mark J. 2021;25(1):76–81.

Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA. Oh DJJoc, psychology c. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. 2010;78(2):169.

Irving JA, Dobkin PL, Park JJC. Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: a review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). 2009;15(2):61–6.

Plaza I, Demarzo MMP, Herrera-Mercadal P, García-Campayo, JJJm. uHealth Mindfulness-based Mobile Applications: Literature Review and Analysis of Current Features. 2013;1(2):e2733.

Heckenberg RA, Hale MW, Kent S, Wright BJJP. Behavior. An online mindfulness-based program is effective in improving affect, over-commitment, optimism and mucosal immunity. 2019;199:20–7.

Shapiro SL, Brown KW, Biegel GMJT. psychology eip. Teaching self-care to caregivers: Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. 2007;1(2):105.

Lee H, Choi S. Factors affecting fatigue among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18).

Zou X, Liu S, Li J, Chen W, Ye J, Yang Y, et al. Factors Associated with Healthcare workers’ insomnia symptoms and fatigue in the fight against COVID-19, and the role of Organizational Support. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:652717.

Stocchetti N, Segre G, Zanier ER, Zanetti M, Campi R, Scarpellini F et al. Burnout in Intensive Care Unit Workers during the Second Wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a single Center cross-sectional Italian study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11).

Kemper KJ, Mo X, Khayat RJTJA, Medicine C. Are mindfulness and self-compassion associated with sleep and resilience in health professionals? 2015;21(8):496–503.

Lee S, Mu C, Gonzalez BD, Vinci CE, Small BJJSH. Sleep health is associated with next-day mindful attention in healthcare workers. 2021;7(1):105–12.

Carmody J, Reed G, Kristeller J. Merriam PJJopr. Mindfulness, spirituality, and health-related symptoms. 2008;64(4):393–403.

Howell AJ, Digdon NL, Buro K, Sheptycki ARJP, Differences I. Relations among mindfulness, well-being, and sleep. 2008;45(8):773–7.

Palagini L, Hertenstein E, Riemann D. Nissen CJJosr. Sleep Insomnia and Mental Health. 2022;31(4):e13628.

Kredlow MA, Capozzoli MC, Hearon BA, Calkins AW, Otto MWJJobm. The effects of physical activity on sleep: a meta-analytic review. 2015;38:427–49.

Korompeli A, Chara T, Chrysoula L, Sourtzi P, editors. Sleep disturbance in nursing personnel working shifts. Nursing forum. Wiley Online Library; 2013.

Alimoradi Z, Jafari E, Broström A, Ohayon MM, Lin C-Y, Griffiths MD et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) on quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2022;64:101646.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all study participants who were involved and contributed to the procedure of data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Bureau Project of Wenzhou (grant no. Y20210635) and the Jinhua Science and Technology Bureau (grant no. 2022-3-097).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.D: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft; P.H and F.Y: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. X.H, W.C, L.Y, A.F, X.M, M.L, Y.C, D.C, H.Z, Q.C and Z.F: Investigation, Data curation, S.N, and Q.H: Methodology, Review & Editing; Project administration, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research followed the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in Jinhua Municipal Central Hospital (No. 20222220101). Informed consent was obtained from all research participants prior to the online survey, who could withdraw at any time or from any item of their own desire.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, C., Hu, P., Yan, F. et al. The mediating role of sleep quality in the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and fatigue in Chinese nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Nurs 22, 471 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01642-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01642-w