Abstract

Introduction

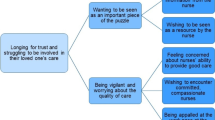

Intensive care unit patients and families experience significant stress. It creates frustrations, nervousness, irritability, social isolation for patients, anxiety, and depression for families. An open visitation policy with no time or duration limits may assist in reducing these negative experiences. However, most Jordanian and regional hospitals within the Middle-East and Northern Africa (MENA) have not implemented this strategy.

Purpose

To evaluate nurse managers' and nurses' perspectives on the effects of an open visitation policy at intensive care units (ICUs) on patients, families, and nurses' care.

Method

A cross-sectional, descriptive, and comparative survey design was used.

Results

A total of 234 nurses participated in the study; 59.4% were males, and 40.6% were females. The mean of their age was 28.6 years, with a mean of 4.1 years of experience. Nurses generally had negative perceptions and attitudes toward the open visitation policy and its consequences on the patient, family, and nursing care.

Conclusions

ICU managers and staff nurses did not favor implementing an open visitation in their units despite its known benefits, international recommendations, and relevance and compatibility with the local religious and cultural context. A serious discussion regarding this hesitation from the side of the healthcare professionals should be started to find a suitable solutions that consider the benefits of the open visitation policy and the challenges that prevent its implementation in the Jordanian and Arabic cultures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Families of patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) are exposed to several distressful events that are often experienced as anxiety, stress, and even depression [1,2,3]. Open visitation, is one of the strategies that managers and policymakers recommended to lessen this stressful experience. [1, 4, 5] Open visitation policy is imposing no restrictions on the time or duration of the visit, this policy's advantages and disadvantages differ from patient to family to ICU workers. [4, 6, 7] The main advantage of the open visiting policy is the positive psychological effect on the patient and the family because they are not separated for long periods, instead there is no restrictions on the duration of the visit. [4, 8,9,10] It helps patients by providing a support system, creating a more familiar environment and encouraging flexibility [8, 11]. The presence of family helps improve the patient's well-being and serves as a relief from hospital routine [12]. Open visitation is a significant element of composing a patient and family-centered approach and is considered a top priority by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses [13, 14].

Some studies even suggested that the quality of life of survivors and relatives is positively influenced by a good relationship between them and the ICU team. Open visitation has been reported to strengthen and enhance this relationship [9, 15, 16] decrease anxiety and depression, and improve satisfaction among family members [7, 17]. Finally, among the reported benefits of open visiting to the healthcare professionals is that it increases their satisfaction as they provide more comprehensive care and the improved trust with the patient's relatives [9, 14].

Even though the attendance of family and friends may support patients during their stay in a very unfamiliar and stressful environment, the effect of open visiting hours on ICU staff is still controversial [6, 9, 18, 19]. The main disadvantage of open visiting from the perspective of healthcare professionals is the distraction that this approach can cause to care in the ICU and the increase in stress when handling patients in the presence of their family members for long hours per day [4]. Also, when being at the bedside, family members will need continuous information to be delivered, which may adversely affect the ICU care delivery [20].

The issue of open visitation is similarly relevant for Jordan and the surrounding region. In this region, the Islamic religion and Arab culture are dominant, with the family lying at the core of the social structure. Kinship, family structure, varying roles among family members, extended family, and support systems are distinctive features of the local culture and religion that must be incorporated into the competent, sensitive, and holistic nursing care [21]. Family members see visiting, being with, and caring for unwell relatives as a form of worship or a religious act. These are critical and sensitive subjects within the Islamic religion and Arabic culture. Therefore, family members may request to be present throughout the care of the critically ill or injured family to be with them, follow their religion, and ensure that their loved one receives the best possible care [22].

Open vistitation could directly impact nurses’ work environment and flow. Due to the serious conditions of the patients they care for, nurses are subject to considerable work-related stress and are more likely to feel compassion fatigue. Nurses are also burdened with a more workload. In these conditions, in addition to caring for critically ill patients, nurses must also tend to the numerous demands of visitors, which adds to compassion fatigue and lowers professional quality of life. ICU nurses have therefore being resistant to open visitation despite its advantages for patients and their families [4, 5, 7].

In conclusion, the dilemma is still present in the ICU setting as to which visiting policy adequately incorporates the family members into the plan of care of the patient while at the same time allowing the ICU workers to safely manage the care of the ICU patient without any conflict situation occurring [23]. To address this dilemma in the best possible manner, the beliefs and attitudes of ICU stakeholders such as managers, staff nurses, families, and patients need to be researched as their views will influence the type of visiting policy that will be implemented.

However, observations from inside the healthcare system in Jordan and the region indicated that this area is still unclear, unconsidered, and lacks a clear understanding of the stakeholders' views and care policies and guidelines. Therefore, this study will take an initial step and explore managers' and nurses' perspectives on the open visitation policy at ICUs in Jordan and its effects on patients, families, and their care.

Research aim

To explore the perceptions of the mangers’ and nurses’ about the effect of the open visitation policy on patient care, family satisfaction, and nurses' abilities to provide care in the ICUs in Jordan.

Methods

Research design

A descriptive and comparative design was used to meet the objective of this study.

Setting and sample

Five hospitals (one public hospitals and four private hospitals) that reflect the largest number of nurses working in the Critical Care Units in Jordan were selected to recruit the study participants. The selected hospitals represent the governmental, private, and academic sectors, the three main sectors that provide health services in the country. Nursemanagers and staff nurses in the Critical Care Units from the accessed hospitals such as Intensive Care, Coronary Care, Emergency, and Burn Units and working in the ICUs for more than one year were included in the study. The required sample size was calculated using G* Power analysis based on a medium effect size of 0.15, an α of 0.05, a power of 0.8 and independent t-test as a statistical test for analysis. Based on these assumptions, it was found that the needed sample size was 230. Therefore, at the conclusion of the study, 234 nurses were recruited conveniently.

Data collection

Data were collected from June 2021 to October 2021 using structured, self-administered questionnaires. A list of all nurse mangers and staff nurses in the selected settings was prepared and recruitment was managed via appointments arranged by the researcher and trained data collector. The researcher and trained data collector informed the respondents about the nature, and purpose of the study and that participation was voluntary. They were further told that they had the right to withdraw at any time they wished. The researcher collected data from public and private hospitals with the help of a data collector who has no conflict of interest with the participants and was trained by the researcher on the data collection procedure to ensure consistency. In addition, the researcher and research assistant were available to participants to clarify any inquiries. The questionnaires required 10–15 min to be completed.

Instrument

First, the current visitation practices at ICU questionnaire was used. This questionnaire was developed by the researchers and included 7 questions about the present visitation at the ICU in participants' facilities. Questions in the questionnaire covered four domains: (1) restrictions on visits which includes four question; visiting duration allowed currently, number of visitors allowed at one time, limit on who visits, the maximum visiting permitted time per visitor. (2) Exceptions in the visiting policy to be made, (3) specific times during the day when no visitors are allowed, and (4) availability of a written visiting policy for the ICU.

Second, the Beliefs and Attitudes toward Visitation in ICU Questionnaire (BAVIQ) was used [17, 19]. The questionnaire assesses ICU nurses' beliefs and attitudes toward different aspects of visitation and visiting hours. The BAVIQ questionnaire consists of two parts and is divided into four subscales; the first part is about nurses' beliefs about the consequences of visitation on the patient (Qs 1 – 9), family (Q 10 and 11), and nursing care. The second part is nurses' attitudes towards visiting, and these included questions twenty-one to thirty-two. The questionnaire uses a five-point Likert scale with answer options ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire have been confirmed in previous studies [24, 25], which reported a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of around 0.78.

Ethical consideration

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from Institutional Review Board (IRB), Faculty of Nursing, Applied Science Private University; (IRB No. Student 1–5- 2021–1). Permission from the corresponding author was taken to use the BAVIQ. It was clarified to the nurses that participation is voluntary and that returning a filled questionnaire means the approval of the nurses to participate in the study. The study was anonymous; no identifiers were required from the participants.

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 25) was used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the study sample. Descriptive statistics of the variables (i.e., frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) were reported for the current visitation policy at ICU. Nurses' beliefs about the consequences of visitation on the patient, family, and organization of care were reported as well as their attitudes towards visiting. An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare nurses' attitudes toward visiting and the consequences of visitation on the patient, family, and nursing care for private and public hospitals. The significance level (P-value) of less than 0.05 was considered a statistically significant result.

Results

Participants' characteristics

A total of 234 nurses participated in the study. Among participants, 139 were males, and 95 were females. The mean age of participants was 28.6 ± 4.4 years. More than half of the sample, 134 (57.3%), were from private hospitals, and almost all of them (99.1%) had a bachelor's degree in nursing, with a majority (88.0%) working as clinical bedside nurses. Finally, participants have a mean experience duration of 4.1 years, as shown in Table 1.

Participants' responses regarding visiting policy

Findings related to the visitation policy are shown in Table 2; 35.9% of participants reported that visitation is currently limited to two visiting times per day, 38.9% of the total participants said that visitation is presently limited to two visitors at a time, and 50.0% responded that maximum visiting time currently is between 5–10 min. A 46.6% responded that exceptions in the visiting policy could be made when the patient is dying. While 55.1% responded that there were not any specific times during the day when no visitors were allowed. 57.7% of the participants respond that they do not have an official written visiting policy at their ICU.

Consequences of visitation on the patient, family, and nursing care

The item that received the highest score was "An open visiting policy interferes with direct nursing care." The five highest-rated consequences of the open visiting policy were about the undesired consequences of the policy on direct nursing care. Participants believed that this policy would interfere with the nursing care (Mean = 3.8), nurses would spend more time providing information to the family (Mean = 3.8), open visiting would interfere with the communication between the nurses (Mean = 3.7), it would increase the risk of errors (Mean = 3.7), and finally disturbs patients rest (Mean = 3.6). The first desired consequence of the policy was mentioned in the sixth rank. It was that the visitors can help the patient interpret information (Mean = 3.6) and that the visitation has a beneficial effect on the patient (Mean = 3.5). Then after that immediately, the negative consequences were reported again and included: "An open visiting policy makes nurses nervous because they are afraid to make a mistake" (Mean = 3.5), "the open visiting policy interferes with the adequate planning of the nursing care process" (Mean = 3.5), "the open visiting policy will create adverse hemodynamic responses in patients" (Mean = 3.4) and violate upon their privacy" (Mean = 3.4). The least rated item was that the open visiting policy is essential for the patient's recovery (Mean = 2.8). Table 3 presents all the items and their rating ordered from the top to the lowest.

Participants' responses regarding nurses' attitudes toward visiting

Participants generally had negative attitudes toward the open visiting policy. The highest-rated statement was that the available visiting policy must be adopted only when the patient is dying (Mean = 3.5) or strictly when a patient has emotional needs (Mean = 3.2). Also, participants highly rated the statement that a strict visiting policy must be adopted when a family has problems adhering to the policy (M = 3.1). Finally, and probably the most negative statement moderately rated by participants is that the open visiting policy should be adapted based on the culture or ethnicity of the patient (Mean = 2.8). The least rated statements by participants were that the number of visitors in a day, the number of visitors together, and the length of visit should not be limited (Mean ± SD = 2.2 ± 1.2, 2.3 ± 1.1, 2.3 ± 1.1 repectively) as shown in Table 4.

Inferential analysis

An independent samples t-test showed that nurses in the different hospital sectors hold the same perceptions and attitudes toward the open visiting policy and its consequences on patients and nursing care (M [SD]; Patients:29.8 [4.3] vs. 29.4 [4.7], t = 0.75, p = 0.46; Nursing care: 30.5 [5.0] vs. 31.5 [4.9], t = 1.48, p = 0.14). However, these participants differ in their scores for the visitation effect on the family, and nurses working in a private hospital have the most positive perceptions and attitudes (M [SD]; 6.6 [1.4] vs. 6.0 [2.2], t = 2.583, p = 0.011).

Discussion

When patients get treatment, especially in ICUs, healthcare institutions usually exclude family members or at least limit their presence or contribution to their patient's care; this is a finding of this study and has also been reported in previous studies. [22] Even during critical care and life-threatening events, family presence may be limited, and relatives may only be able to attend to their patient after treatment or when they are dying. As a result, patients and their family members are deprived of the opportunity to confront obstacles together, strengthen, empower, and soothe one another. [22] This study, therefore, would address a significant issue for the Jordanian and regional contexts. It has revealed the severe practice gap in the ICUs in Jordanian hospitals and the local culture and needs.

In Jordan and the surrounding Arab countries, Islamic beliefs and Arabic culture significantly impact all aspects of daily life and the population's needs. Moreover, these countries' social, economic, and healthcare systems also operate within the same context. [26] Therefore, comprehensive healthcare requires consideration of all essential patient and family aspects and needs, including religious and cultural considerations. [27] This is especially essential during difficult times such as illness, when Muslims usually rely more on religion. [20, 28, 29]

In Islam and among Muslims, life is regarded as a divine trust, and both health and illness are viewed as periods of stress requiring patience and resilience. Family members consider visiting, being with, and attending to the needs of ill individuals as a sort of worship or religious act. [29] In Islamic theology and Arabic culture, these are significant and delicate topics. Therefore, family members may request to be present during the care of critically ill or injured family members to be with them, stick to their religion, and guarantee that their beloved family member receives the best care possible. Understanding these demands and desires is crucial for providing appropriate, high-quality, and comprehensive care. Awareness of these culturally and religiously sensitive elements could help enhance cooperation and communication between healthcare providers and patients/family members. [30]

From a theoretical nursing point of view, Leininger (1996), a renowned nursing theorist and scholar, created a comprehensive care model to assist nurses in taking into account all of the factors that may affect care [31]. The model incorporated technology, religious and philosophical elements, kinship and social variables, cultural values, beliefs, ways of life, political and legal factors, economic issues, and educational aspects. Even in high-acuity, high-stress healthcare settings, such as critical care units, it is essential to provide complete, and competent treatment.

International evidence supports these views; studies have confirmed that the patient's family must be close by in times of health emergencies or injuries. Very early evidence that explored this issue reported that the most pressing requirements for families and relatives during their patient's stay at the hospital and critical illnesses were to have frequent contact with the patient, a sense of hope, and the belief that hospital staff cared about the patient, knowledge of the prognosis, and information, support, and reassurance from hospital staff, and to provide care and assistance [32, 33]. Despite the knowledge of the desire of family members to be close to ailing loved ones, especially during severe illnesses, and the early evidence in this regard, it appears that healthcare professionals in the Jordanian and similar Arabic contexts are still reluctant to adopt the family-centered approach and instead prefer to exclude family members during such times. Interestingly, this disparity exists even though healthcare professionals and patients share the same cultural and religious beliefs in many Arabic nations. However, in their practice, the wishes of family members to be present during the care provided for their loved ones in critical conditions are not consistently honored. In addition, there is a lack of regulations, guidelines, and research on the subject, even though the patient populations in these nations are primarily traditional and religious and have strong ties within families and extended social networks. [21, 34]

This reluctance of healthcare professionals to adopt a family-centered approach may be attributed to the context of intensive care units, which are highly complex and demanding. The management of patients requiring critical care typically relies on advanced technologies as life-sustaining treatment tools, which poses additional hurdles for healthcare personnel who must manage these technologies in the presence of family members if such a policy is adopted. In addition, the presence of family members in critical care settings and during treatment for critical illnesses is connected with several psychological and social issues and trauma, including shock, denial, guilt, and fear of losing the patient. In addition to providing direct patient care, healthcare professionals may confront several added duties, including providing psychological and emotional support for family members and taking their needs into account throughout patient care. [35, 36] For instance, if a family member cannot handle the stress of the circumstance, they may become another patient. Additionally, critical care practitioners must also prioritize the immediate requirements of their patients. [37] This may place the patient's family members in a peripheral position and give them the false sense that they are being ignored or are at risk if left unattended.

Conclusions and recommendations

A holistic approach to care necessitates that health professionals acknowledge the significance of satisfying patients' and their families' needs. In the context of critical care, despite the challenges and added duties, clear communication and healthy relationships between healthcare personnel and family members are crucial. During illness, family members frequently fill a void that cannot be satisfied by medical professionals. Therefore, it is essential for personnel in critical care to establish collaborative connections with patients' family members, including exchanging information and offering required assistance.

In addition, certain religious beliefs and cultural values in Islam and Arabic cultures may provide support in the setting of severe illness, which may be helpful for healthcare practitioners. These religious beliefs and cultural values may also be linked to specific requirements (e.g., the need to continuously be with a patient to offer support and assistance and enable them to better comprehend and recover from a crisis). Ignoring such needs may compromise the quality of care and result in unintended effects. In contrast, family inclusion and open and regular communication with a patient's family, including discussing religious and cultural factors (as appropriate), can help identify and address special support needs. Clarification of these concerns and communication-specific training may consequently reduce the workload of critical care professionals and enhance the quality of care provided.

The literature has extensively explored the importance of familial and social elements in a family's presence during care for life-threatening diseases or injuries. Family members desire to assist and advocate for patients in critical times. In addition, maintaining family ties amid critical situations may positively affect the mental health of patients and their relatives. In the Arabic and Muslim environment, social bonds and family life are of utmost importance; all family members (both immediate and extended), friends and coworkers are expected to assist criticall ill family members. ICU visitation during COVID-19 was further compromised, it was possible again in May 2021 in our study settings, but with some restrictions (starting with a maximum of two family members for 1 h per day, and later on two persons for 2 h in the morning and two persons for 2 h in the evening). Critical care workers must recognize this responsibility and collaborate with each patient's family to ensure that this requirement can be provided while adhering to the environment's necessary limits.

Limitations

Certain limitations of the current study merit mention. First, the present study settings and participants were selected conveniently from one geographical area. Even though this area contains most of the health services providers in the country, this issue may still affect the generalizability of the current findings. Second, the perceptions of nurses were only included. Future studies may explore the perceptions of families also.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chiang VCL, Lee RLP, Ho FM, Leung CK, Tang YP, Wong WS, et al. Fulfilling the psychological and information need of the family members of critically ill patients using interactive mobile technology: A randomised controlled trial. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;41:77–83.

Saeid Y, Salaree MM, Ebadi A, Moradian ST. Family intensive care unit syndrome: An integrative review. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2020;25(5):361.

Abdul Halain A, Tang LY, Chong MC, Ibrahim NA, Abdullah KL. Psychological distress among the family members of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients: A scoping review. J Clin nurs. 2022;31(5–6):497–507.

Bélanger L, Bussières S, Rainville F, Coulombe M, Desmartis M. Hospital visiting policies-impacts on patients, families and staff: A review of the literature to inform decision making. J Hosp Adm. 2017;6(6):51–62.

McKenna SP. Nurses' Perceptions of Open Visiting Policy in the Adult Intensive Care Unit: An Integrative Review. Master Thesis. Rhode Island College: The School of Nursing; 2019.

Milner KA, Goncalves S, Marmo S, Cosme S. Is open visitation really “open” in adult intensive care units in the United States? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;29(3):221–5.

DeLano AR, Abell CH, Main ME. Visitation policies on the adult ICU: Nurses’ satisfaction and preferences. Nurs Manag. 2020;51(2):32–6.

Büyükçoban S, Bal ZM, Oner O, Kilicaslan N, Gökmen N, Ciçeklioğlu M. Needs of family members of patients admitted to a university hospital critical care unit, Izmir Turkey: comparison of nurse and family perceptions. PeerJ. 2021;9: e11125.

Naef R, Brysiewicz P, Mc Andrew NS, Beierwaltes P, Chiang V, Clisbee D, et al. Intensive care nurse-family engagement from a global perspective: A qualitative multi-site exploration. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;66: 103081.

Tabah A, Ramanan M, Bailey RL, Chavan S, Baker S, Huckson S, et al. Family visitation policies, facilities, and support in Australia and New Zealand intensive care units: A multicentre, registry-linked survey. Aust Crit Care. 2021;7314(21):00103.

Khatri Chhetri I, Thulung B. Perception of nurses on needs of family members of patient admitted to critical care units of teaching hospital, Chitwan Nepal: a cross-sectional institutional based study. Nurs Res Pract. 2018;2018:1369164.

White A, Parotto M. Families in the intensive care unit: A guide to understanding, engaging, and supporting at the bedside. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(3): e99.

Kokorelias KM, Gignac MA, Naglie G, Cameron JI. Towards a universal model of family centered care: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–11.

McAndrew NS, Schiffman R, Leske J. A theoretical lens through which to view the facilitators and disruptors of nurse-promoted engagement with families in the ICU. J Fam Nurs. 2020;26(3):190–212.

Sviri S, Geva D, Vernon vanHeerden P, Romain M, Rawhi H, Abutbul A, et al. Implementation of a structured communication tool improves family satisfaction and expectations in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2019; 51:6–12.

Olabisi OI, Olorunfemi O, Bolaji A, Azeez FO, Olabisi TE, Azeez O. Depression, anxiety, stress and coping strategies among family members of patients admitted in intensive care unit in Nigeria. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2020;13: 100223.

Imanipour M, Kiwanuka F. Family nursing practice and family importance in care–Attitudes of nurses working in intensive care units. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2020;13: 100265.

Seyedfatemi N, Mohammadi N, Hashemi S. Promoting patients health in intensive care units by family members and nurses: A literature review. J Educ Health Promot 2020; 9.

Yakubu YH, Esmaeilie M, Navab E. Nurses Beliefs And Attitudes Towards Visiting Policy In The Intensive Care Units Of Ghanaian Hospitals. Adv Biosci Clin Med. 2018;6(4):25–32.

Elay G, Tanriverdi M, Kadioglu M, Bahar I, Demirkiran O. The needs of the families whose relatives are being treated in intensive care units and the perspective of health personnel. Ann Med Res. 2020;27(3):0825–9.

Al-Yateem N, AlYateem S, Rossiter R. Cultural and Religious Educational Needs of Overseas Nurses Working in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Holist Nurs Pract. 2015;29(4):205–15.

Saifan A, Al-Yateem N, Hamdan K, Al-Nsair N. Family attendance during critical illness episodes: Reflection on practices in Arabic and Muslim contexts. Nurs Forum 2022:Online ahead of print.

Hurst H, Griffiths J, Hunt C, Martinez E. A realist evaluation of the implementation of open visiting in an acute care setting for older people. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–11.

Zolfaghari M, Haghani H. Nurses viewpoint about visiting in coronary care unit. Iran J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;2(4):16–24.

Alizadeh R, Pourshaikhian M, EMAMI SA, KAZEMNEJAD LE. Visiting in intensive care units and nurses’beliefs. 2015.

Al-Yateem N, Rossiter R, Robb W, Ahmad A, Elhalik MS, Albloshi S, et al. Mental health literacy among pediatric hospital staff in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):390.

Almutairi AF, Rondney P. Critical cultural competence for culturally diverse workforces: toward equitable and peaceful health care. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2013;36(3):200–12.

Hweidi IM, Al-Shannag MF. The needs of families in critical care settings—are existing findings replicated in a Muslim population: a survey of nurses’ perception. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;116(4):518–28.

Al-Hassan MA, Hweidi IM. The perceived needs of Jordanian families of hospitalized, critically ill patients. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004;10(2):64–71.

Alshahrani S, Magarey J, Kitson A. Relatives’ involvement in the care of patients in acute medical wards in two different countries—an ethnographic study. J Clin nurs. 2018;27(11–12):2333–45.

Leininger M. Culture care theory, research, and practice. Nurs Sci Q. 1996;9(2):71–8.

Hampe SO. Needs of the grieving spouse in a hospital setting. Nurs Res. 1975;24(2):113–20.

Molter NC. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: a descriptive study. Heart lung. 1979;8(2):332–9.

Van Dam NT, Van Vugt MK, Vago DR, Schmalzl L, Saron CD, Olendzki A, et al. Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018;13(1):36–61.

Wong P, Liamputtong P, Koch S, Rawson H. Families’ experiences of their interactions with staff in an Australian intensive care unit (ICU): a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2015;31(1):51–63.

Yin King Lee L, Lau YL. Immediate needs of adult family members of adult intensive care patients in Hong Kong. J Clin nurs 2003; 12(4):490–500.

Monks J, Flynn M. Care, compassion and competence in critical care: A qualitative exploration of nurses’ experience of family witnessed resuscitation. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30(6):353–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank data collectors, all nurses and nurse mangers who made this research successful.

Funding

No funding was received to conduct this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HIA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. SJ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. NA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. FR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. MA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been contacted according to declaration of Helsinki 1964. The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB), Faculty of Nursing, Applied Science Private University.

Each participant signed an informed consent before the participation in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Maloh, H.I.A.A., Jarrah, S., Al-Yateem, N. et al. Open visitation policy in intensive care units in Jordan: cross-sectional study of nurses' perceptions. BMC Nurs 21, 336 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-01116-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-01116-5